Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has impacted cancer care globally. The aim of this study is to analyze the impact of COVID‐19 on cancer healthcare from the perspective of patients with cancer.

Methods

A cross‐sectional survey was conducted between June 19, 2020, to August 7, 2020, using a questionnaire designed by patients awaiting cancer surgery. We examined the impact of COVID‐19 on five domains (financial status, healthcare access, stress, anxiety, and depression) and their relationship with various patient‐related variables. Factors likely to determine the influence of COVID‐19 on patient care were analyzed.

Results

A significant adverse impact was noted in all five domains (p = < 0.05), with the maximal impact felt in the domain of financial status followed by healthcare access. Patients with income levels of INR < 35 K (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.61, p < 0.05), and 35K‐ 100 K (AOR = 1.96, p < 0.05), married patients (AOR = 3.30, p < 0.05), and rural patients (AOR = 2.82, p < 0.05) experienced the most adverse COVID‐19‐related impact.

Conclusion

Delivering quality cancer care in low to middle‐income countries is a challenge even in normal times. During this pandemic, deficiencies in this fragile healthcare delivery system were exacerbated. Identification of vulnerable groups of patients and strategic utilization of available resources becomes even more important during global catastrophes, such as the current COVID‐19 pandemic. Further work is required in these avenues to not only address the current pandemic but also any potential future crises.

Keywords: access to healthcare, cancer surgery, COVID‐19, financial support, psychological health

1. INTRODUCTION

In the second week of December 2019, a cluster of patients infected with a novel coronavirus was identified in Wuhan city, Hubei province in China. 1 This unique virus was named the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. 2 The condition was described as Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) by the World Health Organization (WHO), which declared its outbreak a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. 3 , 4 There have been more than 100 million people infected, and over 2 million lives have been lost due to this virus worldwide. After the United States, the number of infected cases has been second highest in India. 5

This global pandemic has created one of the most difficult challenges to both the developed as well as developing nations of the world. It has not only affected the healthcare system of countries but has also created immense problems related to economic and developmental issues. The problem in healthcare is not only limited to the control and saving the lives of patients infected with COVID‐19 but also to deliver medical care to patients with other non‐COVID‐19‐related health problems. In this scenario, the care of patients with cancer has been severely disrupted since the emergence of the novel COVID virus. 6 , 7 It has been noted that the disruption in cancer services has been proportional to the spread of this infection. 8

Unique challenges have emerged in terms of access to oncology facilities by the patients and the inability of the COVID‐19 overwhelmed medical systems to deliver care to patients with a cancer diagnosis. Additionally, loss of jobs or family earnings, social isolation, and loneliness caused by the COVID‐19 pandemic has worsened the already existing distress prevalent in the lives of cancer patients. 9 To date, we are not aware of any study that has attempted to analyze and quantify the type and scope of problems that are faced by patients with cancer in accessing care in a low to middle‐income country. Analyzing the adverse impacts of COVID‐19 from a patient's perspective is very important to develop solutions that can guide health professionals and ultimately benefit the patients. The aim of this study is to analyze the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on disruptions in cancer care delivery from the patient's perspective by utilizing a patient‐designed questionnaire.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This interviewer‐administered, paper‐based, cross‐sectional questionnaire survey was conducted in the Department of Surgical Oncology, at a tertiary care referral center, from June 19, 2020, to August 7, 2020. The study was started after receiving approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (reference code: 5th ECMIB‐COVID‐19/P2). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Full anonymity of the study participants and confidentiality of data was maintained throughout the study. We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines for reporting this study. 10 The framework of this study was based on the theory of phenomenology and a constructivist approach. Due to the limitation of time and resources during the COVID‐19 pandemic, a nonprobability purposive sampling method was selected. We restricted the study period to 50 days, and that explains the criteria for sampling saturation.

2.2. Researcher characteristics

Our group included five expert clinicians with more than ten years of experience in patient care and research. To avoid bias, one of the nonclinical coauthor conducted all the interviews. The sole interviewer had no prior contact or relationship with the patients.

2.3. Sample

Our study population consisted of cancer patients more than 18 years of age with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, 1, or 2 scheduled to be seen in our Surgical Oncology Clinic. To avoid any psychological distress that can potentially affect the responses to the questionnaire, it was mandatory for patients to be aware of their cancer diagnosis before being interviewed. With these inclusion criteria, our initial cohort consisted of 1117 patients. The following exclusion criteria were applied: confirmed or clinically suspected COVID‐19 diagnosis, any previous neurological or psychiatric disorders, patients with advanced or metastatic disease that may have required a noncurative or palliative treatment, which can increase the psychological stress and those that refused to provide consent. After excluding these cases, we were left with a cohort of 403 patients. Due to the time‐compressed nature of our clinic schedules (where the survey was conducted), some patients were unable to complete the survey completely. This led to a total number of 310 patients that were included in the study for analysis.

2.4. Survey questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed after face‐to‐face in‐depth interviews with the patients (Supplementary material 1). It was divided into three parts (A) demographics information, (B) body of questionnaire with instructions to choose responses, and (C) concluding statements of gratefulness for participation (Supplementary material 2). The body of the questionnaire was divided into a total of five domains, namely financial domain, access to healthcare, anxiety, stress, and depression. All questions were closed‐ended.

2.5. Procedure for data collection

Before the start of the study, a researcher was trained by the principal investigator on how to conduct this survey. Patients were screened in the clinics. All eligible patients were then sent to a separate room. The questionnaire was administered to the patients by the trained researcher. Only if the patient was unable to read the local language, the questionnaire was read out to the patient and the interviewer used visual aids for the responses. During this process, no one else was present besides the patient and researcher. Only one patient was interviewed at a time. To avoid any coercion, clinicians were kept unaware of the patient's consent to participate in the survey. No attempts were made to analyze the data until the enrollment of the last patient.

2.6. Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic characteristics of patients and responses obtained from the questionnaire. The value assigned for a response was used to generate a COVID‐19 “Impact score” for each domain. The difference in the mean impact score of each domain was compared between groups using an unpaired t‐test and analysis of variance (ANOVA; repeated‐measures ANOVA, or one‐way ANOVA test). A χ 2 test was used to test the association between two categorical variables. To identify the factors predicting the impact of COVID on the cancer patients, binary logistic regression analysis was used, followed by univariate and multivariate analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using statistical software “Statistical package for social sciences” version‐23 (SPSS‐23, IBM).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic profile of study population and questionnaire responses

In this study, 310 cancer patients were surveyed and included for analysis. The baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of our patients were male (60.3%), from rural locations (73.2%) and married (89.2%). Nearly one‐third of our patients were self‐employed and approximately 35% were illiterate. Table 2 summarizes the responses to the questionnaire. All the patients (n = 310, 100%) were aware of the spread of COVID‐19 (Question 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (N = 310)

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 48.0 (20.0) |

| Age groups, n (%) years | |

| 18–30 | 26 (8.3) |

| 31–50 | 166 (53.6) |

| 51–65 | 95 (30.7) |

| >65 | 23 (7.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 187 (60.3) |

| Female | 123 (39.7) |

| Domicile, n (%) | |

| Rural | 227 (73.2) |

| Urban | 83 (26.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 277 (89.2) |

| Unmarried | 9 (3.0) |

| Widow/Widower/Separated | 24 (7.8) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Self‐earning (Farmer/Business) | 97 (31.2) |

| Housewife | 117 (37.8) |

| Private job | 30 (9.7) |

| Student | 7 (2.3) |

| Daily wages (Laborers/Street vendors) | 39 (12.6) |

| Retired | 10 (3.2) |

| Government job | 10 (3.2) |

| Annual income, n (%) | |

| <35 K | 78 (25.1) |

| 35 K–100 K | 60 (19.3) |

| 100 K–200 K | 12 (3.9) |

| >200 K | 9 (3.0) |

| Dependent | 151 (48.7) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| Illiterate | 111 (35.8) |

| Below secondary school | 81 (26.2) |

| Secondary school | 41 (13.2) |

| Senior secondary school | 34 (10.9) |

| Graduation | 34 (10.9) |

| Postgraduation | 9 (3.0) |

Note: Annual income represented in INR (Indian Rupee); K = 1000.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Table 2.

Patients responses to the survey questionnaire

| Responses, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about Corona | ||

| 1. | Are you aware of the spread of Corona disease in India? | Yes, 310 (100) |

| Financial domain | ||

| 2. | Have you lost your job/income or primary source of income due to Corona? | Yes, 133 (43) |

| No, 177 (57) | ||

| 3. | Have your spouse or any family member lost their job or primary source of income due to Corona? | Yes, 160 (52) |

| No, 150 (48) | ||

| 4. | Are you getting treatment under any Government health schemes like Ayushman Bharat, Asadhya patient card, CM/PM fund, Vippan yojana, BPL card, and Insurance? | Yes, 58 (19) |

| No, 252 (81) | ||

| If yes, do you think that treatment benefits under these schemes are being affected by Corona? | Yes, 35 (60) | |

| No, 23 (40) | ||

| If no, are you worried that the financial/economic impact of Corona will make your treatment hard for you? | Yes, 32 (13) | |

| No, 220 (87) | ||

| Healthcare access | ||

| 5. | Did any hospital refuse to treat the symptoms of your disease due to fear of Corona? | Yes, 71 (23) |

| No, 239 (77) | ||

| 6. | Was your treatment denied by a hospital due to the unavailability of the Corona infection testing report? | Yes, 65 (21) |

| No, 245 (79) | ||

| 7. | Do you feel that during this period of corona, you were charged higher consultation fees by the hospital for your treatment? | Yes, 54 (17) |

| No, 256 (83) | ||

| 8. | Are you scared of getting Corona infection from other patients or hospital staff? | Yes, 244 (79) |

| No, 66 (21) | ||

| 9. | Were you denied Financial or Practical Support by your relative or friends during Corona? | Yes, 138 (45) |

| No, 172 (55) | ||

| 10. | You experienced any difficulty in reaching the hospital during Corona. | Not at all, 98 (32) |

| A little, 133 (43) | ||

| Quite a bit, 73 (24) | ||

| Very much, 6 (2) | ||

| 11. | You feel that your medical problems were not properly addressed or listened to by medical staff during Corona. | Not at all, 287 (93) |

| A little, 21 (7) | ||

| Quite a bit, 1 (0) | ||

| Very much, 1 (0) | ||

| 12. | You experience any accommodation issues while visiting the hospital due to Corona. | Not at all, 122 (39) |

| A little, 131 (42) | ||

| Quite a bit, 54 (17) | ||

| Very much, 3 (1) | ||

| 13. | You are worried about delaying your cancer treatment and progression of the disease during Corona. | Not at all, 46 (15) |

| A little, 71 (23) | ||

| Quite a bit, 164 (53) | ||

| Very much, 29 (9) | ||

| 14. | You feel that you will not be able to follow up in the hospital in time due to fear of Corona. | Not at all, 65 (21) |

| A little, 101 (33) | ||

| Quite a bit, 123 (40) | ||

| Very much, 21 (7) | ||

| Stress domain | ||

| 15. | Any picture or thought associated with the Corona comes to your mind. | Not at all, 190 (61) |

| A little, 106 (34) | ||

| Quite a bit, 12 (4) | ||

| Very much, 2 (1) | ||

| 16. | You avoid letting yourself get upset when you think about Corona | Not at all, 189 (61) |

| A little, 100 (32) | ||

| Quite a bit, 21 (7) | ||

| Very much, 0 (0) | ||

| 17. | You try not to talk to each other about Corona | Not at all, 117 (38) |

| A little, 136 (44) | ||

| Quite a bit, 57 (18) | ||

| Very much, 0 (0) | ||

| 18. | You feel angry thinking about Corona. | Not at all, 89 (29) |

| A little, 74 (24) | ||

| Quite a bit, 82 (26) | ||

| Very much, 65 (21) | ||

| 19. | You have trouble sleeping because of Corona. | Not at all, 237 (76) |

| A little, 52 (17) | ||

| Quite a bit, 21 (7) | ||

| Very much, 0 (0) | ||

| 20. | Your appetite has decreased/increased due to Corona. | Not at all, 237 (76) |

| A little, 55 (18) | ||

| Quite a bit, 18 (6) | ||

| Very much, 0 (0) | ||

| Anxiety domain | ||

| 21. | You get nervous any time due to Corona. | Never, 133 (43) |

| Sometimes, 143 (46) | ||

| Often, 31 (10) | ||

| Always/Almost, 3(1) | ||

| 22. | You have had any of the physical reactions like sweating, shaking, heart pounding, or breathing difficulty in the absence of any physical exertion without doing any work because of Corona. | Never, 210 (68) |

| Sometime, 87 (28) | ||

| Often, 12 (4) | ||

| Always/Almost, 1 (0) | ||

| 23. | You feel difficulty in concentrating while doing daily activities due to Corona. | Never, 197 (64) |

| Sometime, 102 (33) | ||

| Often, 11 (4) | ||

| Always/Almost, 0 (0) | ||

| 24. | You feel anxious about your future because of Corona | Never, 38 (12) |

| Sometime, 112 (36) | ||

| Often, 116 (37) | ||

| Always/Almost, 44 (14) | ||

| Depression domain | ||

| 25. | You feel sad and helpless because of Corona | Never, 59 (19) |

| Sometime, 141 (45) | ||

| Often, 88 (28) | ||

| Always/Almost, 22 (7) | ||

| 26. | You find it difficult to initiate your routine because of Corona | Never, 206 (66) |

| Sometime, 92 (30) | ||

| Often, 11 (4) | ||

| Always/Almost, 1 (0) | ||

| 27. | You feel that your life is meaningless because of Corona | Never, 104 (34) |

| Sometime, 104 (34) | ||

| Often, 80 (26) | ||

| Always/Almost, 22 (7) | ||

| 28. | You feel that you cannot experience any positive feeling at all due to Corona. | Never, 120 (39) |

| Sometime, 83 (27) | ||

| Often, 72 (23) | ||

| Always/Almost, 35 (11) | ||

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Effect of COVID‐19 pandemic on various domains

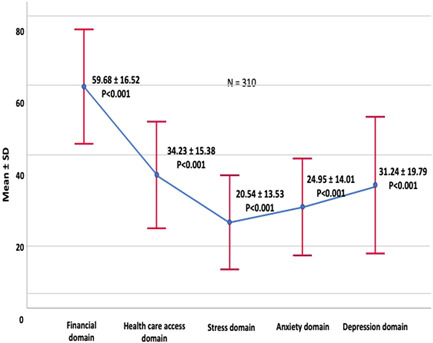

The effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic was studied on the five major domains of the survey instrument. The impact score measuring this effect on various domains showed statistically significant different scores, with the maximum score for the financial domain (59.68 ± 16.52), followed by healthcare access domain (34.23 ± 15.38). The least effect was noticed on the stress domain (20.54 ± 13.53). These findings are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Error bars showing COVID‐19 Impact Score. Higher score showing the worst impact of the pandemic (SD = standard deviation, N = total numbers of patients). COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3. Association of demographic variables with the domains

The impact score of all five domains was calculated for each of the demographic variables. The association between them was statistically significant for each demographic variable (P ≤ 0.001 each).

Comparison of the individual domain was also performed with each demographic variable (Table 3). The maximum impact score in the financial domain was seen in the age group of 31–50 years, males, married, daily wagers, having a senior secondary level of education, and patients with an annual income of INR 35K–100K. The maximum impact score in the access to healthcare domain was seen in patients of age group 31–50 years, those coming from rural areas, daily wagers, patients with annual income INR < 35 K, and those with education below the secondary school.

Table 3.

Association of demographic variables with impact scores of domains

| Financial domain | Health Care Access Domain | Stress domain | Anxiety domain | Depression domain | Total | Multiple Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (All domains combined) | p value | (p < 0.05) | |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||

| 18–30 | 54.4 (17.3) | 32.2 (12.6) | 26.9 (15.4) | 26.0 (15.3) | 38.1 (17.3) | 35.5 (10.3) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 2–3, 4, 5 & 3–4) | ||||||||

| 31–50 | 62.4 (16.1) | 35.6 (15.9) | 20.7 (13.2) | 25.6 (13.7) | 32.1 (20.2) | 36.2 (10.6) | All | |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| 51–65 | 57.5 (16.4) | 34.4 (15.0) | 20.4 (12.7) | 25.4 (13.9) | 30.7 (19.7) | 34.6 (9.9) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 4) | ||||||||

| > 65 | 54.3 (16.1) | 25.4 (13.3) | 12.6 (13.9) | 16.7 (13.5) | 19.6 (14.6) | 26.7 (10.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4 & 4–2, 3) | ||||||||

| p value | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.009 | 0.001 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 63.2 (16.6) | 34.4 (16.1) | 21.3 (13.5) | 24.9 (14.0) | 30.5 (20.1) | 35.7 (11.2) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| Female | 54.3 (14.9) | 34.0 (14.3) | 19.3 (13.5) | 25.1 (14.1) | 32.4 (19.3) | 33.7 (9.5) | All | |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| p value | <0.001 | 0.838 | 0.203 | 0.902 | 0.405 | 0.091 | ||

| Domicile | ||||||||

| Rural | 59.5 (16.3) | 35.5 (14.3) | 20.9 (13.2) | 25.5 (14.0) | 31.6 (19.4) | 35.5 (9.8) | <0.001 | All (Except 5–2) |

| Urban | 60.0 (17.2) | 30.7 (17.5) | 19.5 (14.5) | 23.4 (14.2) | 30.3 (20.8) | 33.3 (12.3) | All (Except 5–2, 3–4) | |

| p value | 0.821 | 0.015 | 0.457 | 0.243 | 0.634 | 0.102 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 60.5 (16.7) | 34.8 (15.5) | 21.2 (13.5) | 25.7 (14.2) | 31.7 (19.7) | 35.6 (10.5) | <0.001 | All (Except 2–5) |

| Unmarried | 53.7 (11.1) | 31.1 (15.2) | 22.8 (14.3) | 18.5 (9.1) | 36.1 (16.7) | 32.9 (9.5) | All (Except 1–2, 3, 4) | |

| Widow/Widower/Separated | 52.8 (14.5) | 28.5 (13.3) | 12.3 (11.3) | 19.0 (11.1) | 24.3 (20.8) | 28.3 (9.7) | All (Except 5–2, 3, 4) | |

| p value | 0.049 | 0.125 | 0.007 | 0.033 | 0.163 | 0.004 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Self‐earning (Farmer/Business) | 64.3 (15.4) | 35.1 (15.6) | 22.3 (13.1) | 27.1 (14.6) | 33.2 (19.8) | 37.0 (10.3) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| Housewife | 54.4 (15.1) | 34.4 (14.3) | 19.1 (13.4) | 25.6 (14.2) | 32.0 (19.7) | 33.9 (9.5) | All | |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| Private Job | 63.3 (14.8) | 32.8 (19.2) | 22.9 (14.9) | 22.5 (13.0) | 25.6 (19.1) | 34.6 (12.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4 & 4–3, 2) | ||||||||

| Student | 52.3 (11.5) | 33.3 (16.8) | 26.2 (14.2) | 20.2 (9.4) | 38.1 (17.2) | 34.6 (10.1) | 0.001 | All (Except 5–1, 2, 3, 4–3, 2 & 3–2) |

| Daily wages | 69.2 (15.5) | 38.5 (13.8) | 21.4 (13.0) | 23.5 (11.6) | 32.3 (20.6) | 38.4 (9.6) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 5–2, 4 & 4–3) | ||||||||

| Retired | 50.0 (17.6) | 22.3 (11.3) | 15.0 (13.6) | 17.5 (16.4) | 16.7 (12.4) | 25.0 (10.9) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4, 4–3, 2 & 3–2) | ||||||||

| Government job | 43.3 (17.9) | 23.0 (13.5) | 11.1 (12.3) | 19.2 (14.2) | 25.8 (21.3) | 24.6 (11.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–1, 2, 3, 4 & 4–1, 2, 3) | ||||||||

| p value | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.067 | 0.155 | 0.096 | <0.001 | ||

| Annual income (INR) | ||||||||

| <35 K | 64.3 (16.0) | 37.9 (14.9) | 23.4 (13.4) | 25.9 (14.5) | 35.1 (20.8) | 38.3 (10.8) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 5–2 & 4–3) | ||||||||

| 35K–100 K | 69.2 (13.6) | 35.5 (16.9) | 21.6 (13.9) | 26.6 (12.7) | 30.1 (17.3) | 37.6 (9.7) | All | |

| (Except 5‐2, 4 & 4‐3) | ||||||||

| 100K–200 K | 57.0 (18.1) | 29.7 (19.7) | 19.4 (8.4) | 24.3 (15.7) | 23.6 (17.7) | 31.6 (11.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–2,3, 4–2,3 & 3–2) | ||||||||

| >200 K | 40.7 (12.1) | 21.9 (8.8) | 9.2 (8.8) | 16.7 (14.4) | 15.7 (17.9) | 21.60 (7.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–1, 2, 3, 4 & 4–1, 2, 3) | ||||||||

| Dependent | 54.8 (15.2) | 32.9 (14.4) | 19.3 (13.6) | 24.3 (14.0) | 31.2 (19.9) | 33.2 (9.9) | All | |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| p value | <0.001 | 0.010 | 0.021 | 0.307 | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Illiterate | 61.3 (16.2) | 36.4 (15.3) | 20.3 (13.5) | 26.9 (14.2) | 34.4 (20.4) | 36.64 (10.8) | <0.001 | All |

| (Except 5–2) | ||||||||

| Below secondary school | 61.5 (17.2) | 37.5 (14.4) | 21.6 (15.1) | 25.5 (13.7) | 31.8 (20.1) | 36.7 (10.5) | All | |

| (Except 5–2 & 4–3) | ||||||||

| Secondary school | 53.2 (17.9) | 28.6 (14.5) | 20.7 (13.1) | 22.1 (15.9) | 27.4 (18.2) | 30.9 (10.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4 & 4–3, 2) | ||||||||

| Senior secondary school | 63.2 (9.9) | 34.1 (15.9) | 18.5 (10.8) | 21.6 (11.6) | 30.9 (18.9) | 34.7 (7.5) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 4 & 4–3, 2) | ||||||||

| Graduation | 55.4 (16.2) | 28.8 (15.1) | 21.1 (12.7) | 24.5 (13.3) | 27.7 (17.6) | 31.9 (10.7) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4, 4–3, 2 & 3–2) | ||||||||

| Post‐Graduation | 55.5 (20.4) | 24.1 (14.3) | 18.5 (16.2) | 22.2 (14.4) | 18.5 (21.9) | 28.3 (12.3) | All | |

| (Except 5–2, 3, 4, 4–3, 2 & 3–2) | ||||||||

| p value | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.904 | 0.271 | 0.095 | 0.003 |

Note: Data presented in mean ± standard deviation; p < 0.05 significant; INR = Indian Rupee; K = 1000.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

The maximum impact score in the stress domain was seen in patients aged between 18 and 30 years, unmarried, and those with an annual income of INR < 35 K. The maximum impact score in the anxiety domain was seen in patients aged between 18 and 30 years and married patients. The maximum impact score in the depression domain was seen in the group of patients aged between 18 and 30 years and those with an annual income of INR < 35 K (Table 3).

3.4. Demographic predictors of the COVID‐19 impact

From the demographic data that was analyzed, we noted that income groups, marital status, and area of residence had a statistically significant impact on univariate analysis (p < 0.05). In multivariate analysis, all these three variables maintained their significance as independent factors associated with the impact of COVID‐19 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographic predictors of the COVID‐19 impact on cancer patients

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Variables | ||||||

| Annual income (INR) | 0.003 | 0.017 | ||||

| < 35 K | 2.04 | 1.15–3.61 | 0.015 | 1.61 | 1.02–2.13 | 0.047 |

| 35K–100 K | 2.24 | 1.19–4.24 | 0.013 | 1.96 | 1.00–3.83 | 0.048 |

| 100K–200 K | 0.69 | 0.21–2.26 | 0.536 | 0.64 | 0.19–2.18 | 0.479 |

| > 200 K | 0.12 | 0.02–0.98 | 0.048 | 0.10 | 0.01–0.82 | 0.033 |

| Dependent | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Marital status | 0.014 | 0.045 | ||||

| Married | 3.69 | 1.48–9.18 | 0.005 | 3.30 | 1.27–8.57 | 0.014 |

| All other | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Domicile | ||||||

| Rural | 1.78 | 1.07–2.96 | 0.026 | 1.82 | 1.06–3.13 | 0.028 |

| Urban | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

Note: Binary logistic regression used; p < 0.05 significant; K = 1000.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we tried to identify the impact of the COVID‐19 on cancer patients scheduled for surgery and have attempted to characterize their personal perspective about the problems faced by them during the pandemic. To date, we are not aware of a study that has attempted to obtain the perspectives of cancer patients waiting for surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic from a resource‐challenged country.

The demographic characteristics of the patients reflect the usual cross‐section of patients visiting a tertiary care government cancer hospital in India with some differences. The male to female ratio was 1·5:1, which is different from recent studies by Ghosh et al (1:2), and Romito et al (1:1). 11 , 12 This variation could be due to the different types of cancers included in the studies. We see more cases of oral cancer, which are common in males, whereas Ghosh et al included more patients with breast cancers. 11 More than 80% of our patients were middle‐aged, and the majority of them were between 31 and 50 years of age group. These findings were observed because of the high incidence of tobacco‐related cancers in these age groups.

About two‐thirds of our patients were literate. As we see patients predominantly from rural areas, the literacy rate is consistent with the prevailing literacy rate in the rural parts of our state. We could not find any comparison with the existing literature related to this finding.

Occupation wise about one‐third of our patients were self‐employed and were either farmers or small businessmen. Only 50% of patients had some source of earning, and the majority of them had a low annual income. The other half of the patient population was dependent, which includes 95% of the female patients who were housewives. This reflects that a high proportion of our patients depend on other family members for their treatment. These findings explain the difficulties faced by patients that can range from commute/lodging to the hospital, especially from remote rural areas, treatment‐related expenditures, visiting tertiary care centers during this pandemic and the psychological stress associated with these issues.

All patients (100%) were aware of the coronavirus pandemic since the study was initiated after the 68‐day nationwide lockdown was lifted on May 31st, 2020. Nearly half (50%) of patients reported a loss of their family earnings. Romito et al reported that only 5% of their patients had financial difficulties. 12 Around 45% of patients could not arrange finances and social support from their relatives or friends. A study from Oxford found that nearly half (52%) of their cancer patients felt isolated from family and friends. 13 Although around 20% of patients could have access to government funds, 60% of them believed that it would be difficult for them to utilize these funds due to the ongoing pandemic.

Nearly one‐fifth of our patients faced denial of treatment by other hospitals due to fear of an ongoing pandemic. In a study from Turkey, more than 80% of cancer patients were concerned about treatment interruption. 14 Most of our patients (80%) were scared of getting exposed to coronavirus infection during the hospital stay. In another study, 60% of patients expressed concern about getting exposed to COVID‐19 while receiving chemotherapy in the hospital. 11 Around two‐third of patients experienced some difficulty in reaching the hospital, and about 60% faced problems in arranging accommodation. This is because the majority of our patients come from rural areas. Approximately 80% of patients expressed concern that their subsequent follow‐up would not be on time. Gebbia et al. 15 found that 37% of their patients suggested postponing their follow‐up visit due to the pandemic. The majority (93%) of our patients expressed faith in the medical staff regarding their treatment, which is a hallmark and very positive aspect of healthcare in India. This level of respect in a trustworthy relationship is not only beneficial to the patient but can also contribute to the emotional well‐being of physicians.

Almost 70% of patients expressed anger thinking about the pandemic. Nearly 25% of our patients suffered from insomnia as compared to 30% reported by Shi et al. 16 During daily activities, about 64% of patients in our study did not have any problem concentrating on their work. In contrast, Buntzel et al. 17 noted that 61% of patients in their study experienced restrictions in carrying out their daily activities.

Anxiety due to the pandemic was detected in 62% of patients with cancer, 18 which is much higher than the rate (one‐third) noted in the general population. 13 , 16 In our study, about 88% of patients were anxious about their future, whereas 81% felt sad and helpless. Two‐third of patients had felt that their life has become meaningless, and they could not experience a positive feeling in life. Another study reported depressive symptoms in 31% of patients with cancer. 12 This can be explained by the fact that in addition to carrying a burden of cancer, they had to struggle with the difficulties posed by the pandemic.

The impact of COVID‐19 on all five domains was found significant across all age groups (p < 0.05 for each domain). A greater psychological impact was seen in patients aged 18–30 years. Depression was the commonest symptom, followed by stress and anxiety, respectively. Studies in the general population showed a greater psychological impact of COVID‐19 in young people. 19 , 20 Higher impact in financial and healthcare access domain was seen in patients aged 31–50 years (Table 3).

About 52% of our patients experienced financial difficulties compared to Romito et al study in which only 5% of patients had financial difficulties. 12 Males were much more impacted financially than females (mean difference, 63 vs. 54, p < 0.001;Table 3). This could be due to current practices in some parts of India, where males tend to be the main earning members in the family. Our study did not show any difference in the levels of anxiety, stress, and depression between males and females. This is similar to the findings noted by Ozamiz–Etxebarria et al., 19 where gender played no role in the psychological impact. In contrast, some other authors documented that females reported more anxiety, stress, and fear compared to male patients with cancer. 12 , 21

Patients who belonged to rural areas were impacted significantly more than those living in urban areas in terms of healthcare access (mean difference, 35 vs. 31, p = 0.015). Our hospital is located in an urban area, and as urban people have better access to transportation facilities, they were less impacted in accessing healthcare.

Married cancer patients had a greater financial impact and level of anxiety compared with unmarried patients. This may be because married people have more dependents, which increases their concerns for the family and expenses. The unmarried group had a greater level of stress, which could be because the majority of them live alone. Wang et al did not find any association between anxiety and marital status in the general population. 18

Most of the patients who lost their jobs were daily wage earners (laborers and street vendors) as they were most impacted by the lockdown and closure of the industries. This had impacted their financial status and access to healthcare.

Those earning INR < 35 K annually had more stress and depression. Whereas those with annual income INR 35K–100 K were more impacted financially. Those earning INR < 35 K had less financial impact than those earning more as they were supported by government funds for their cancer treatment.

Those having education below a secondary school level and illiterate patients had more problems in healthcare access. Those with senior secondary education were more impacted financially. Overall, illiterate and those with below secondary school of education were impacted the most due to COVID‐19. The level of education was not associated with psychological impact.

Our study showed higher odds of COVID‐19 impact in the following patient populations: those with a low annual income (below INR 100 K), married patients, and patients from rural areas. This is not surprising as patients from the higher‐income bracket were able to obtain better care due to their financial stability.

There are several limitations to this study. The major limitation of the present study is in the generalizability of the study results to other situations, with different levels of COVID burden, variations in hospital setting and practices, and differences in the patient population. In addition, the results of the survey should be interpreted with caution as patients were participating in the survey at a time of high stress. However, it did truly reflect the experiences of the patients being treated by us in a government‐funded tertiary care facility in the most populous state in India, with over 220 million inhabitants.

In conclusion, the COVID‐19 pandemic has impacted the surgical care for cancer patients to a great extent. This impact is evident in all five key domains studied. Our study has identified patients at higher risk due to this pandemic. This information can serve as a guiding tool for the hospitals to prioritize cancer care during this pandemic when the entire focus has been shifted to addressing the COVID‐19 pandemic. Also, it is critical to understand the difficulties encountered by the patients by knowing their perspective, as highlighted by the present study. While the hospitals should continue providing COVID‐19 treatment, they should also be diligent in maintaining timely and quality cancer care without any delay. It is essential to develop patient‐oriented policies, which can prioritize cancer care even during global crises such as the current COVID‐19 pandemic.

SYNOPSIS

During this pandemic, where the main focus has shifted to managing COVID‐19 patients, delivery of cancer care needs to remain a priority so as to avoid the detrimental effects of delayed care on recovery and long‐term survival. The aim of our study is to identify obstacles faced by cancer patients in accessing surgical care. It is our hope that the results of our study will help hospital authorities to design new patient‐oriented plans and streamline existing policies to mitigate the short‐term and long‐term consequences of this pandemic on vulnerable cancer patients.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The study was started after the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee (reference code: 55th ECMIB‐COVID‐19/P2). No financial support or grant was utilized.

Rajan S, Akhtar N, Tripathi A, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on cancer surgery: Patient's perspective. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123:1188–1198. 10.1002/jso.26429

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data will be made available by the corresponding author after a reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, et al. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . 2020. WHO Director‐General's Remarks at the Media Briefing on 2019‐nCoV on 11 February 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020

- 4. Whitworth J. COVID‐19: a fast evolving pandemic. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114(4):241‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Retrieved from http://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 6. Cancer referrals fell from 40,000 to 10,000 per week in April . In NHS Providers 14/05/20. 2020.

- 7. Shrikhande SV, Pai PS, Bhandare MS, et al. Outcomes of elective major cancer surgery during COVID 19 at Tata Memorial Centre: implications for cancer care policy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e249‐e252. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Preliminary results: rapid assessment of service delivery for noncommunicable diseases during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 29 May 2020. https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/rapid-assessment-of-service-delivery-for-ncds-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e32. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghosh J, Ganguly S, Mondal D, Pandey P, Dabkara D, Biswas B. Perspective of oncology patients during COVID‐19 pandemic: a prospective observational study from India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:844‐851. 10.1200/GO.20.00172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romito F, Dellino M, Loseto G, et al. Psychological distress in outpatients with lymphoma during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1270. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kosir U, Loades M, Wild J, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 on the cancer care of adolescents and young adults and their well‐being: Results from an online survey conducted in the early stages of the pandemic [published online ahead of print, July 22, 2020]. Cancer. 2020. 10.1002/cncr.33098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guven DC, Sahin TK, Aktepe OH, Yildirim HC, Aksoy S, Kilickap S. Perspectives, knowledge, and fears of cancer patients about COVID‐19. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1553. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gebbia V, Piazza D, Valerio MR, Borsellino N, Firenze A. Patients with cancer and COVID‐19: a WhatsApp messenger‐based survey of patients' queries, needs, fears, and actions taken. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:722‐729. 10.1200/GO.20.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2014053. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buntzel J, Klein M, Keinki C, Walter S, Buntzel J, Hubner J. Oncology services in corona times: a flash interview among German cancer patients and their physicians. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(10):2713‐2715. 10.1007/s00432-020-03249-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ozamiz‐Etxebarria N, Dosil‐Santamaria M, Picaza‐Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga‐Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID‐19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Niveles de estrés, ansiedad y depresión en la primera fase del brote del COVID‐19 en una muestra recogida en el norte de España. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(4):e00054020. 10.1590/0102-311X00054020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross‐sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11‐17. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Falcone R, Grani G, Ramundo V, et al. Cancer care during COVID‐19 era: the quality of life of patients with thyroid malignancies. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1128. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available by the corresponding author after a reasonable request.