Abstract

Objectives

The COVID‐19 epidemic is affecting the entire world and hence provides an opportunity examine how people from different countries engage in hopeful thinking. The aim of this study was to examine the potentially facilitating role of perceived social support vis‐à‐vis hope as well as the mediating role of loneliness between perceived social support and hope. This mediating model was tested concurrently in the UK, the USA, and Israel.

Methods

In April 2020, as the first wave of the virus struck the three aforementioned countries, we assessed perceived social support, loneliness, and hope in 400 adults per country (N = 1,200). Assessments in the UK/USA were conducted via the Prolific platform, whereas in Israel they were conducted via Facebook/WhatsApp.

Results

In all three countries, perceived social support predicted elevated hope, although the effect was smallest in the UK. Loneliness mediated this effect in all three countries, although full mediation was attained only in the UK.

Conclusions

Perceived social support may facilitate hope in dire times, possibly through the reduction of loneliness.

Practitioner Points

Findings are consistent with respect to the potentially protective role of perceived social support vis‐à‐vis hope.

Perceived social support may increase hope through decreasing loneliness.

In the UK, the above‐noted mediating effect of loneliness appears to be stronger than in Israel and the USA.

Elevated levels of perceived social support should serve as a desired outcome in individual and group psychotherapy, as well as in community based interventions.

Keywords: COVID‐19, hope, international reactions to crisis, loneliness, perceived social support

Background

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, as people around the world experienced social distancing, lockdowns, and economic constraints, hope has arguably been a much‐needed resource. Hope has been shown to be an important mechanism in predicting self‐efficacy and motivation towards achieving important goals in life (Snyder, 2002). Hopeful thinking is a learned and dynamic trait that enables a future perspective to be integrated into a present state. In this context, hope is likely to play an important role in influencing people’s perceptions and sense of confidence in the future as well as their ability to face this challenging period and overcome barriers and obstacles (Cheavens, Heiy, Feldman, Benitez, & Rand, 2019; McDermott et al., 2017).

In the current study, we therefore sought to examine relevant mechanisms related to increased levels of hopeful thinking: perceived social support and decreased loneliness. Although the experiences of the pandemic and the impact of its disruptions varied in different places around the world, we aimed to explore whether the proposed model would be valid in three different countries. Since we examined the relationship between the variables before a vaccine had been developed, levels of uncertainty regarding the future were high, and therefore, hope was considered a mental resource. Our hypothesis was that social support would play an important role in facilitating hope beliefs and introducing future perspectives in the three countries examined (the UK, the USA, and Israel). In addition, we hypothesized that in these countries, loneliness would mediate the connection between social support and hope.

Hopeful thinking

Hope theory has been defined as ‘a cognitive set that is based on a reciprocally derived sense of successful (1) agency (goal‐directed determination) and (2) pathways (planning of ways to meet goals) (Snyder et al. 1991, p. 571). International studies have identified the same two elements of hope in different cultures: pathways and agency (Edwards & McClintock, 2018). Snyder (2002) suggested that since hope is the expectation for a positive future, it could be applied to research in different cultures (Snyder, 2002). This assumption has been confirmed in several studies in which the cross‐cultural examination of hope revealed a similar construct, especially when addressing a global measure. For example, comparisons of a hope scale among college students in the United States and China revealed the same psychological structure of hope in both (Li, Mao, He, Zhang, & Yin, 2018). A comparison of different ethnic groups in American society, including European Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans also indicated similarities in the manner in which hope was related to indices of behaviour (such as problem solving) and adjustment (Chang & Banks, 2007). A comprehensive review of cultural differences regarding hope revealed the similarity of the hope construct in many cultures. Since some differences between groups were found when comparisons were focussed on the elements of hope, it was recommended to use the global score in cross‐cultural studies (Edwards & McClintock, 2018). Following the results of this survey of the literature, the current study examined the global concept of hope.

In various studies, hope has been found to play an important role in adaptation to a challenging reality (Dixson, Keltner, Worrell, & Mello, 2018; Lucas et al., 2020). Difficulties related to learning disabilities and attention deficit disorder have been shown to reduce hope, in turn reducing academic self‐efficacy (Ben‐Naim, Laslo‐Roth, Einav, Biran, & Margalit, 2017). Similarly, hope has been found to contribute to patients’ adaptation to chronic disease (Rideout & Montemuro, 1986; Soundy, Roskell, Elder, Collett, & Dawes, 2016) and cancer (Rustøen, Cooper, & Miaskowski, 2010). Furthermore, hope has been identified as an adaptation mechanism among mothers who care for children with chronic physical conditions (Horton and Wallander, 2001). In this sense, hope can be considered a coping mechanism (Gallagher & Lopez, 2018).

In the current study, as mentioned, we sought to predict hope during a global crisis (the COVID‐19 pandemic) in three different countries. In the absence of an obvious solution to the crisis, we hypothesized that hope for a positive future would play an important role in mental health and coping and that social relationships would play an important role in stimulating hope. We focussed on perceived social support as a predictor and on loneliness as a mediator.

Perceived social support and hopeful thinking

Perceived social support is an overarching concept used to describe situations in which assistance given by one person can help another. For the most part, researchers have assumed that perceived social support is an important measure of promoting success, positive self‐image, and adaptability (Magro, Utesch, Dreiskämper, & Wagner, 2019). The concept of support is based on the premise that confidence in close and meaningful interpersonal relationships is an important resource for both personal and socioemotional development in various life stages (Zhu, Wang, & Chong, 2016).

Social support is considered an important coping resource during times of crisis. Theories of effective support have proposed that support should address recipients’ needs (Zee, Bolger & Higgins, 2020). Social support has been identified as essential for resilience to stress (Ozbay et al., 2007; Wilks, 2008) as well as for enhancing life satisfaction (Zhang, 2017) and reducing depression (Gariepy, Honkaniemi, & Quesnel‐Vallee, 2016; Kim et al., 2017; Zhang, 2017). There is scant literature on the psychological role of social support during epidemic outbreaks, but some researchers have focussed on its positive role in adaptation. For example, a systematic thematic review on psychological adjustment of healthcare workers during an infectious disease outbreak (SARS) identified social support as the mechanism most effective in minimizing future negative psychological impact (Brooks, Dunn, Amlôt, Rubin, & Greenberg, 2018).

The link between social support and hopeful thinking has been established in several studies. For example, support provided to adolescents in residential care by adult mentors has been associated with an increase in hope (Sulimani‐Aidan, Melkman, & Hellman, 2019). In addition, perceived social support among Chinese children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has been shown to be related to increased hope (Ma, Lai, & Lo, 2017). Social support and hope predicted higher self‐efficacy among college students with learning disorders (Mana et al., 2021). On‐campus social support and hope have both been found to be related to ability to persist in college (D’Amico et al., 2018). Chang et al. (2019) identified hope and social support as an effective adjustment mechanism of resilience to racial discrimination.

As this brief review of the literature demonstrates, there have been prior indications that social support is related to an increase in hope. Nevertheless, the studies mentioned focussed mainly on children and young adults (Ma et al., 2017; Sulimani‐Aidan et al., 2019) and did not target the mechanisms of the possible effect of social support on hope.

A comprehensive survey of the research on the relations between culture and social support (Kim, Sherman, & Taylor, 2008) revealed similarities among Western countries such as the UK, the USA, and Israel in the appreciating and beneficial role of social support in promoting well‐being. In individualistic Western cultures, social support tends to focus on addressing individuals’ emotional needs through approaches such as comforting and esteem‐boosting (Lawley, Willett, Scollon, & Lehman, 2019). Studies have noted the connection between social support, well‐being, and hope in different cultures, for example among college students in the USA (Fruiht, 2015), Hong Kong youth (Du et al., 2016) and Turkish students (Gungor, 2019).

Loneliness and hopeful thinking

Loneliness is a subjective experience that reflects a threat to one’s need to be in close relationships (Teneva & Lemay, 2020). It is the feeling of being without company and is thought to disrupt social integration and increase psychological isolation. In their article on social isolation during the COVID‐19 pandemic, addressing the fact that billions of people are quarantined in their homes, Benerjee and Rai identified loneliness as the main factor that threatens physical and mental well‐being (Banerjee & Rai, 2020). Loneliness is one of the indicators of decrease in well‐being (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2018; Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). Research has shown that it not only affects individuals’ current well‐being, but is also reflected in the biased memories of social exclusion in the past and in thoughts regarding the future (Teneva, & Lemay, 2020). Lonely people may experience lower self‐esteem and negative affect, and this aversive experience may distort their cognition, affecting how they construe their futures, which may independently contribute to negative outcomes and reduced hope.

Various studies have documented the relations between hope and loneliness. In a recent study on bereaved parents, increased levels of loneliness predicted lower levels of hope (Einav & Margalit, 2020). In another study, both hope and loneliness were found to mediate the effect of stress on subjective vitality (Satici, 2020). A study on students’ effort investment and success in school also found hope and loneliness as mediators in predicting student’s school effort (Feldman et al., 2018). In these studies, loneliness was the risk factor, while hope was presented as a protective factor. Countries devote many resources to fighting social loneliness. Recognizing the serious damage caused by loneliness, the UK, for example, has launched a ten‐year national plan to fight the phenomenon (see UK Government, 2018, 2020).

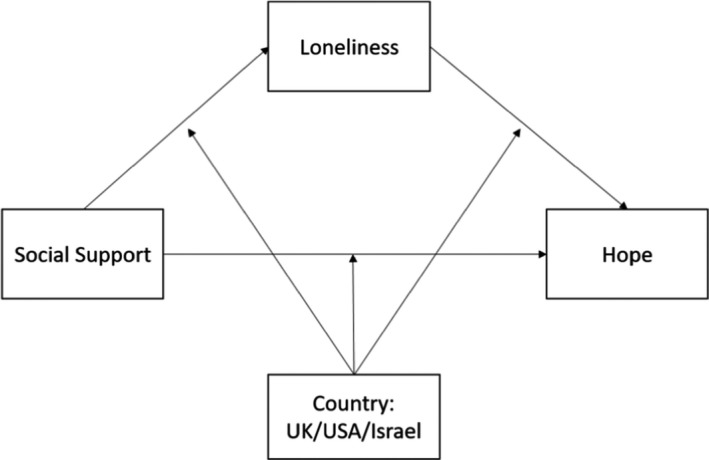

The conceptual model on which the current study is based is presented in Figure 1. We hypothesized that during the global health crisis (COVID‐19), perceived social support would be related to an increase in hope, with loneliness being a mediating mechanism of this relationship. Perceived social support, we hypothesized, would be related to a decrease in loneliness which, in turn, would be related to increased hopeful thinking. We hypothesized that this finding would be consistent across three Western countries: the US, the UK, and Israel. See Figure 1 for model specification.

Figure 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model.

The cultural context

The three countries were chosen in the context of dealing with a global health crisis and the model we propose should be verified beyond possible cultural cross‐cultural differences. The research was conducted in three Western countries with different health policies and practices at a time when they were struggling and coping differently with COVID‐19. In the UK, the National Health Service provides healthcare through different clinics as a citizens’ right, with full access for all. In Israel, healthcare is also a right to which all citizens have full access. However, it is provided differently, by competing sick funds that offer health services around the country. In the USA, health care is not provided as a right but as a commodity to which access may be limited except in emergencies. People must pay for services directly or through their insurance. Thus, although in the UK and Israel the national public health systems are based on law, the services are provided differently (Glied, Wittenberg, & Israeli, 2018). These differences in healthcare practices were also reflected in the different modes of response to the pandemic in the different countries, and later through the different vaccination strategies for COVID‐19.

In terms of the spread of the virus, at the time of data collection, in early April 2020, the US had the highest number of confirmed cases, the UK had a high mortality rate, and Israel was experiencing a lower level of morbidity and very low mortality rates. At the end of data collection, in early April 2020, in the USA there were 395,030 confirmed cases and 12,740 deaths, in the UK 60,737 confirmed cases and 7,097 deaths, and in Israel 9,404 confirmed cases and 71 deaths.

A comparative study of all OECD countries conducted in June 2020 lists the USA as the leader in the number of COVID‐19 cases per million, the UK as the leader in the number of deaths, and Israel as a country with a relatively low level of disease and an extremely low level of deaths per million (Balmford, Annan, Hargreaves, Altoè, & Bateman, 2020). Differences between countries in addressing the outbreak originated in government policies regarding speed of response and policy interventions. Israel was identified as a country that ‘rapidly entered into lockdown and quickly controlled the growth of the virus’, while the USA and the UK were identified as countries that did not respond with due speed and intensity (Balmford et al., 2020).

We hypothesized that, in line with previous findings on culture and social support, and beyond different health crisis management practices in the three countries, people from Western cultures across different countries would benefit from perceived social support during the COVID‐19 crisis. Specifically, we hypothesized that perceived social support would be related to an increase in hope in all three countries and that the alleviation of loneliness was the activating mechanism through which perceived social support would predict hopeful thinking.

Methods

Participants and procedure

One thousand two hundred (1,200) participants from the USA, the UK, and Israel (400 from each country) took part in the present study. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 79 (Mean = 36.29, SD = 12.71). In the USA and the UK, participants were gathered through a prolific panel (online participant recruitment platform) and received monetary compensation. In Israel, participants were gathered through social networks on a voluntary basis. Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The sample in Israel included a higher percentage of women and a slightly higher age than the samples in the UK and USA. We controlled age and gender in the reported statistical analysis. Participants in Israel completed a Hebrew version of the questionnaire that was translated and back‐translated.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Male | Female | Missing | Age | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | M (SD) | n | |

| UK | 198 (49.5%) | 200 (50%) | 2 (0.5%) | 34.27 (11.76) | 400 |

| USA | 170 (42.5%) | 230 (57.5%) | – | 33.68 (10.72) | 400 |

| Israel | 92 (23%) | 308 (77%) | – | 40.92 (14.13) | 400 |

| Total | 460 (38%) | 738 (61.5%) | 2 (0.5%) | 36.29 (12.71) | 1,200 |

Measures

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was examined using an adaptation of the MSPSS (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). The adapted scale consists of four items rated on a seven‐point Likert scale ranging from one (very strongly disagree) to seven (very strongly agree). Higher scores on each of the subscales indicate higher levels of perceived support. In the current study, support from the significant other four‐item subscale was used: (‘There is a special person who is around when I am in need’, ‘I have a special person who is a real source of comport to me’). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .74.

Hope

The Hope Scale (Snyder, 2002) assesses the belief in one’s own ability to pursue desired goals and employ the strategies needed to achieve them with items such as ‘I can think of many ways to achieve my goals in life’. The adaptation used in the current study (Lackaye and Margalit, 2006) consists of six items to which individuals responded using a six‐point Likert scale ranging from one (none of the time) to six (all of the time), where a higher score reflects a higher level of hope. In the current study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .88 was obtained for this measure.

Loneliness

Loneliness was examined with the short version of the emotional and social loneliness scale (Gierveld & Van Tilburg, 2006) with items such as ‘I experience a general sense of emptiness’, ‘There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems’, and ‘I miss having people around’. Responses for the six‐item scale were measured on a four‐point Likert scale ranging from one (very strongly disagree) to four (very strongly agree). In the current study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .95 was obtained.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, zero‐order correlations) for all study variables are presented in Table 2. The results show that perceived social support was positively correlated with hope, while loneliness was negatively correlated with hope. In addition, perceived social support was negatively correlated with loneliness.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social support | 5.73 | 1.50 | 1 | ||

| 2. Hope | 4.14 | 0.86 | 0.323 ** | 1 | |

| 3. Loneliness | 2.09 | 0.62 | −0.509 ** | −0.486 ** | 1 |

p < .001.

Differences between countries in perceived social support, loneliness, and hope

We subjected perceived support, loneliness, and hope to a repeated‐measure ANOVA (in a general linear modelling context) in which the predictors were country and participants’ gender and age. No statistically significant effects were found in the pooled variance of these three variables. However, all three interacted significantly with the repeated‐measure outcomes: country, F[4,2386] = 16.51, p < .001; gender, F [4,2386] = 6.50, p < .01; age, and F[2,2386] = 6.95, p < .001.

Focusing primarily on country, we found that Israel, the UK, and the USA differed with respect to hope F[2,1193] = 19.67, p < .001 and loneliness F[2,1194] = 47.41, p < .001. Only a non‐significant trend was found with respect to perceived social support F[2,1194] = 2.48, p = .08. Post‐hoc comparisons using the Bonferoni method revealed that Israel exhibited higher levels of perceived support (weighted mean: 4.40) than the UK (4.01) and the USA (4.00), which did not differ. The same pattern emerged for loneliness: Israel (1.81), the USA (2.23), and the UK (2.21). The same post‐hoc procedure revealed that the non‐significant trend found for perceived support was driven by Israelis scoring higher than Britons (5.93 vs. 5.57, Bonferroni = 0.000) and only slightly higher than Americans (5.68, Bonferroni = 0.05). Britons and Americans did not differ (Bonferroni = 0.84). Effects involving gender and age, not focal to this report, are available from the authors upon request.

Testing for mediation effect

According to our first hypothesis, we anticipated that the relationship between perceived social support and hope would be mediated by loneliness. We followed MacKinnon's (2008) four‐step procedure to test mediation effect. Multiple regression analysis indicated that in the first step, perceived social support was significantly associated with hope, b = 0.32, p <.001 (see Model 1 in Table 3). In the second step, perceived social support was negatively associated with loneliness, b = −0.49, p < .001 (see Model 2 in Table 3). In the third step, when we controlled for perceived social support, loneliness was negatively associated with hope, b = −0.43, p < .001 (see Model 3 in Table 3). Finally, the bias‐corrected percentile bootstrap method indicated that the indirect effect of social support on hope via loneliness was significant, ab = 0.12, SE = .01, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.14]. Overall, the four criteria for establishing mediation effect were fully satisfied. Therefore, our hypothesis was supported.

Table 3.

Testing for the mediation effect of loneliness on hope

| Predictors | Model 1 (Hope) | Model 2 (Loneliness) | Model 3 (Hope) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Gender | 0.02 | −1.06 | −0.01 | −0.458 | −0.3 | −1.35 |

| Age | 0.05 | 1.96 | −0.16 | −6.65 *** | −0.01 | −0.68 |

| Social Support | 0.32 | 11.69*** | −0.49 | −20.09 *** | 0.10 | 3.57 *** |

| Loneliness | −0.43 | −14.76 *** | ||||

| R 2 | .10 | .28 | .24 | |||

| F | 48.28*** | 159.93*** | 97.29*** | |||

Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. Gender was dummy coded such that 1 = male and 2 = female.

p < .001.

Testing for moderation and/or moderated mediation

In the current study, we expected that perceived social support would be related to increased hope, mediated by loneliness, and that this mediation effect would occur in all three countries: the USA, the UK, and Israel. We therefore defined the country variable as a moderator and expected no moderation effect. We estimated the moderating effect on the following: (1) the relationship between perceived social support and hope (Model 1); (2) the relationship between perceived social support and loneliness (Model 2); and (3) the relationship between loneliness and hope (Model 3). The specifications of the three models are summarized in Table 4. In each model, we controlled for gender and age.

Table 4.

Testing the moderated mediation effect of perceived social support on hope

| Predictors | Model 1 (Hope) | Model 2 (Loneliness) | Model 3 (Hope) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | T | b | t | b | t | |

| Gender | −0.11 | −2.46* | 0.04 | 1.56 | −0.08 | −1.96* |

| Age | 0.00 | .29 | −0.00 | −4.42*** | −0.00 | −1.18 |

| Social Support | 0.19 | 11.44*** | −0.20 | −19.76*** | 0.08 | 4.4*** |

| Country (W1) | −0.38 | −2.95** | −0.14 | −1.71 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Country (W2) | 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.01 | −0.10 | −0.61 | −2.39 |

| Social Support x Country (W1) | 0.04 | 2.09 * | −0.00 | −0.49 | 0.01 | −0.65 |

| Social Support x Country (W2) | 0.03 | 1.40 | −.03 | −2.09 * | 0.06 | 2.14* |

| Loneliness | −0.54 | −12.57*** | ||||

| Loneliness x Country (W1) | −0.10 | −1.83 | ||||

| Loneliness x Country (W2) | 0.19 | 3.09 ** | ||||

| R 2 | .15 | .34 | .26 | |||

| F | 31.88*** | 90.85*** | 43.36*** | |||

Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. Gender was dummy coded such that 1 = male and 2 = female. W1 is a dummy variable comparing UK to USA; W2 variable is a dummy variable comparing UK to Israel.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Moderation could have occurred if the path between perceived social support and hope had been moderated by country (Hayes, 2013). Moderated mediation could have been established if one or both of two patterns had existed: (1) the path between perceived social support and loneliness was moderated by country and/or (2) the path between loneliness and hope was moderated by country. We employed Hayes’s Model 59 of moderated mediation using the PROCESS macro.

As Table 4 shows, in Model 1 there was a significant main effect of perceived social support on hope, b = 0.19, p < .001, and this effect was moderated by country, b = −0.38, p < .001. We plotted predicted hope against perceived social support separately for each of the three countries. Simple slope tests indicated that while the direct path between perceived social support and hope was significant for participants from the USA (b simple_USA = .09, p < .000) and Israel (bsimple_ISR = .14, p < .001), it was not significant for UK participants (b simple_UK = .00, p < .91).

Model 2 indicated that the effect of perceived social support on loneliness was significant, b = −0.20, p < .000, and this effect was moderated by country b = −0.03, p < .05. We plotted predicted loneliness against perceived social support separately for each of the three countries. Simple slope tests indicated that for all three countries, the higher perceived social support was, the lower loneliness was. However, the effect was somewhat stronger for participants from the USA and Israel than for participants from the UK (b simple_UK = −.16, p < .000; b simple_USA = −.21, p < .000; b simple_ISR = −.24, p < .000).

Model 3 indicated that the effect of loneliness on hope was significant, b = 0.08, p < .000, and moderated by country, b = 0.06, p < .05. We plotted predicted hope against loneliness separately for each of the three countries. Simple slope tests indicated that for all three countries, the higher loneliness was, the lower hope was. However, the effect was somewhat stronger for participants from the USA and the UK than for participants from Israel (b simple_USA = −.65, p < .000; b simple_UK = −.62, p < .000; b simple_ISR = −.34, p < .000).

Most importantly, the bias‐corrected percentile bootstrap results indicated that the indirect effect of perceived social support on hope through loneliness existed for all three countries: the USA (b = 0.13, SE = .02, 95% CI = [0.09 0.18]), the UK (b = 0.10, SE = .01, 95% CI = [0.07 0.13]), and Israel (b = 0.08, SE = .02, 95% CI = [0.04 0.12]).

As indicated above, the direct effect of perceived social support on hope was evident for the USA (b = 0.09, SE = .02, 95% CI = [0.04 0.15]) and Israel (b = 0.14, SE = .03, 95% CI = [0.06 0.21]) but not for the UK (b = 0.00, SE = .02, 95% CI = [−0.04 0.05]), meaning that while for the USA and Israel there was a partial indirect mediation effect of perceived social support on hope through mitigation of loneliness and a direct effect of perceived social support on hope, for the UK there was a full mediation effect, that is, perceived social support was related to decreased loneliness and, in turn, increased hope.

To examine the possibility that loneliness was related to a lower perception of social support that was ultimately related to lower levels of hope, we performed a sensitivity analysis and defined an alternative model according to which loneliness predicts social support that predicts hope (see Appendix S1). When we examined this model, the relationship between social support and hope was not significant for the UK. This alternative set‐up, although possible, does not appear to be valid for all the countries we examined.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationships between perceived social support, loneliness, and hope in three different Western countries. To the best of our knowledge, the role of loneliness as a mediating mechanism of the relationship between perceived social support and hope has not yet been established in the context of crisis management.

During a global health crisis, the world can serve as a huge laboratory in which countries can be compared. We asked whether in different countries a similar picture would emerge when the role of perceived social support in the facilitation of hope was considered. Indeed, we found that in three different Western countries: the USA, the UK, and Israel, the pattern was similar: perceived social support was linked to increased hope through a mechanism of reducing loneliness.

One interesting finding was that while in the USA and Israel there was partial mediation between perceived social support and hope through decreased loneliness, in the UK there was full mediation; perceived social support was related to increase in hope solely through decrease in loneliness. This finding is important because it can be of assistance in identifying appropriate, effective interventions focussed on mitigating loneliness.

It has been found that in individualistic cultures such as that of the UK, especially among young people, vulnerability to loneliness is high and loneliness is more intense and long‐lasting than it is in other cultures. Individualistic cultures emphasize self‐reliance and the social contexts in these cultures are chosen relationships, so social networks are loose. The technological advances that enable work from home, online shopping, and the like contribute to the rise of loneliness, especially in individualistic cultures such as that of the UK (Barreto et al., 2020).

While Israeli culture is less individualistic than British culture, in the US levels of individualism are also considered high according to the individualism index defined by Hofstede et al. (2005), so it is not clear why full mediation existed only among participants from the UK. Nevertheless, this finding is in line with actual practice in the field. At the national level, in the UK, loneliness has been identified as a social challenge that must be confronted (UK Government, 2018) and the annual cost of loneliness for employers has been estimated at approximately £2.5 million (Jeffrey et al., 2017). A long‐term national strategy for mitigating loneliness that involves a central committee and countless projects in British society has been defined and is currently being implemented in the field (UK Government, 2020). However, the UK government strategy includes mainly face‐to‐face initiatives (e.g. support groups, transportation for people with disabilities from isolated areas to the city, social clubs, promotion of social engagement). During the COVID‐19 crisis, these face‐to‐face interventions are limited, and effective online perceived social support initiatives should be developed and examined in the future.

Further statistical examinations that we carried out shed additional light on the full mediation of loneliness between perceived support and hope only in the UK. Specifically, we examined the differences in zero‐order correlations between perceived support and hope in each of the three countries. In the UK, this correlation was weaker (r = .21) than in Israel (r = .33) and the US (r = .39). This pattern held after controlling for age and gender using multiple regression (data available from the authors). Thus, from a statistical perspective, the full mediation of loneliness between perceived support and hope only in the UK may stem from the fact that there was less to account for in this link in the UK than in Israel and the USA. Conceptually, this finding strengthens our explanation of the mediating effect. In the UK, perceived social support may be less translatable to hope than it is in other Western countries, which may explain why a national loneliness programme was deemed necessary.

As described above, the relationship between hope, support, and loneliness has been found in various studies in the past and seems to be bi‐directional. Thus, a different order of relationships between these variables could be examined. However, based on our theoretical approach in this distressful COVID‐19 period when we all need more hope, hope served as an outcome variable. Theoretically, we aimed to test a model of resilience and sought to examine the positive role of interpersonal relationships in facilitating hope through possible mitigation of loneliness, and therefore selected perceived social support as the primary independent variable in the current study.

There are already initial reports of an increase in depressive symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis (Huang & Zhao, 2020) and scholars estimate that the risk for an increase in suicide is high (Reger, Stanley, & Joiner, 2020). There are also reports of rising health anxiety and economic anxiety (Bareket‐Bojmel et al., 2020). The current study identified perceived social support as a relevant intervention related to decreased loneliness and increased hope.

Limitations, future research, and interventional implications

The current study has several limitations. The fact that the study data were collected from a single source may increase the risk of common variance (CMV). Some researchers have argued that CMV does not negate most research findings (Spector, 2006). Nonetheless, we used procedural design methods (confidentiality and anonymity and questionnaire segments and separate instructions) to minimize this risk (Podsakoff, 2003). The current study is cross‐sectional, and therefore, it is not possible to determine causality in the described relationships between the variables. As noted above, the relationships between the three variables: social support, loneliness, and hope appear to be bi‐directional. For theoretical reasons, we have examined the chosen configuration of the variables described in the present study, but other configurations may be possible. In addition, the participants in Israel were sampled in a different way than those in the USA and UK and the percentage of women in the Israeli sample was higher than in the other two countries. The overrepresentation of women was controlled in the analysis. The fact that similar patterns of findings were evident in the three countries despite differences in sample characteristics and the fact that the severity of the pandemic and the disruption to everyday life differed at that time between the three countries strengthens the connection between social support, loneliness, and hope.

Nonetheless, future research should involve more balanced samples and longitudinal and experimental designs to examine the long‐term predictive role of perceived social support on loneliness and hope. Future studies should also expand the exploration of the connection between social support and hope through loneliness in non‐Western countries or more collectivists cultures. In‐depth interviews on personal experiences during stressful times that explore different modes of social support, internal cognitive and affective processes during times of loneliness, and goals for the future may expand our understanding of processes and outcomes. Future studies may also focus on developing effective interventions to increase perceived social support, especially in times of social distancing such as the COVID‐19 crisis. These interventions may focus on online social support tools and effective remote support networks. Online social relationships have been identified as a possible source of perceived social support, especially for those with weak in‐person social engagement (Cole, Nick, Zelkowitz, Roeder, & Spinelli, 2017). Thus, using online social support can increase resilience and well‐being. Future studies should develop and test intervention programmes adapted to different population characteristics (e.g. age and culture).

In conclusion, the COVID‐19 epidemic is presenting us with many challenges. In the current study, we found, in three different countries, that perceived social support is related to a decrease in loneliness and an increase in hope. A full mediation mechanism was revealed in the UK, where loneliness is defined as a national risk. Perceived social support can contribute to emotional resilience during this difficult time and relevant interventions and programmes to reduce loneliness during social distancing should be developed. Hopeful thinking at times of crisis is important in enabling us to maintain a positive outlook towards the future.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Liad Bareket‐Bojmel (Formal analysis; Investigation; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing) Golan Shahar (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing) Sarah Abu‐Kaf (Writing – review & editing) Malka Margalit (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing).

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supplementary sensitivity analysis: alternative model.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in ‘OSF’ at DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/Y6QVN.

References

- Balmford, B. , Annan, J. D. , Hargreaves, J. C. , Altoè, M. , & Bateman, I. J. (2020). Cross‐country comparisons of COVID‐19: Policy, politics and the price of life. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 525–551. 10.1007/s10640-020-00466-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D. , & Rai, M. (2020). Social isolation in Covid‐19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(6), 525–527. 10.1177/0020764020922269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareket‐Bojmel, L. , Shahar, G. , & Margalit, M. (2020). COVID‐19‐related economic anxiety is as high as health anxiety: findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel. International journal of cognitive therapy, 1–9, 10.1007/s41811-020-00078-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, M. , Victor, C. , Hammond, C. , Eccles, A. , Richins, M. T. , & Qualter, P. (2020). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110066. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Naim, S. , Laslo‐Roth, R. , Einav, M. , Biran, H. , & Margalit, M. (2017). Academic self‐efficacy, sense of coherence, hope and tiredness among college students with learning disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 18–34. 10.1080/08856257.2016.1254973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K. , Dunn, R. , Amlôt, R. , Rubin, G. J. , & Greenberg, N. (2018). A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(3), 248–257. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T. , & Cacioppo, S. (2018). Loneliness in the modern age: An evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 58, 127–197. 10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T. , & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York, NY: W. W: Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E. C. , & Banks, K. H. (2007). The colour and texture of hope: Some preliminary findings and implications for hope theory and counselling among diverse racial/ethnic groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(2), 94–103. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E. C. , Chang, O. D. , Rollock, D. , Lui, P. P. , Watkins, A. F. , Hirsch, J. K. , & Jeglic, E. L. (2019). Hope above racial discrimination and social support in accounting for positive and negative psychological adjustment in African American adults: Is “knowing you can do it” as important as “knowing how you can”? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(2), 399–411. 10.1007/s10608-018-9949-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheavens, J. S. , Heiy, J. E. , Feldman, D. B. , Benitez, C. , & Rand, K. L. (2019). Hope, goals, and pathways: Further validating the hope scale with observer ratings. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 452–462. 10.1080/17439760.2018.1484937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. A. , Nick, E. A. , Zelkowitz, R. L. , Roeder, K. M. , & Spinelli, T. (2017). Online social support for young people: Does it recapitulate in‐person social support; can it help? Computers in Human Behaviour, 68, 456–464. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico Guthrie, D. , & Fruiht, V. (2018). On‐campus social support and hope as unique predictors of perceived ability to persist in college. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 22, 522–543. 10.1177/1521025118774932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, D. D. , Keltner, D. , Worrell, F. C. , & Mello, Z. (2018). The magic of hope: Hope mediates the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 507–515. 10.1080/00220671.2017.1302915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du, H. , King, R. B. , & Chu, S. K. W. (2016). Hope, social support, and depression among Hong Kong youth: Personal and relational self‐esteem as mediators. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 21(8), 926–931. 10.1080/13548506.2015.1127397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L. M. , & McClintock, J. B. (2018). A cultural context lens of hope. In Gallagher M. W. & Lopez S. J. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of hope (pp. 95–104). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Einav, M. , & Margalit, M. (2020). Hope, loneliness and sense of coherence among bereaved parents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(8), 2797. 10.3390/ijerph17082797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, D. B. , Einav, M. , & Margalit, M. (2018). Does family cohesion predict Children's effort? The mediating roles of sense of coherence, Hope, and loneliness. The Journal of psychology, 152(5), 276–289. 10.1080/00223980.2018.1447434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruiht, V. M. (2015). Supportive others in the lives of college students and their relevance to hope. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17(1), 64–87. 10.1177/1521025115571104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M. W. , & Lopez S. J. (Eds.) (2018). The Oxford handbook of hope. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy, G. , Honkaniemi, H. , & Quesnel‐Vallee, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284–293. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierveld, J. D. J. , & Tilburg, T. V. (2006). A 6‐item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging, 28(5), 582–598. 10.1177/0164027506289723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glied, S. , Wittenberg, R. , & Israeli, A. (2018). Research in government and academia: The case of health policy. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 7(1), 35. 10.1186/s13584-018-0230-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gungor, A. (2019). Investigating the relationship between social support and school burnout in Turkish middle school students: The mediating role of hope. School Psychology International, 40(6), 581–597. 10.1177/0143034319866492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. H. , Hofstede, G. J. , & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (Vol. 2). New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, T. V. , & Wallander, J. L. (2001). Hope and social support as resilience factors against psychological distress of mothers who care for children with chronic physical conditions. Rehabilitation Psychology, 46(4), 382–399. 10.1037/0090-5550.46.4.382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID‐19 outbreak in China: A web‐based cross‐sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, K. , Abdallah, S. , & Michaelson, J. (2017). The cost of loneliness to UK employers. London, UK: New Economic Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. S. , Sherman, D. K. , & Taylor, S. E. (2008). Culture and social support. American Psychologist, 63(6), 518–526. 10.1037/0003-066X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. M. , Stewart, R. , Kang, H. J. , Bae, K. Y. , Kim, S. W. , Shin, I. S. , … Yoon, J. S. (2017). Depression following acute coronary syndrome: Time‐specific interactions between stressful life events, social support deficits, and 5‐HTTLPR. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86, 62–64. 10.1037/0003-066X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackaye, T. D. , & Margalit, M. (2006). Comparisons of achievement, effort, and self‐perceptions among students with learning disabilities and their peers from different achievement groups. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(5), 432–446. 10.1177/00222194060390050501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley, K. A. , Willett, Z. Z. , Scollon, C. N. , & Lehman, B. J. (2019). Did you really need to ask? Cultural variation in emotional responses to providing solicited social support. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219478. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Mao, X. , He, Z. , Zhang, B. , & Yin, X. (2018). Measure invariance of Snyder's Dispositional Hope Scale in American and Chinese college students. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 21(4), 263–270. 10.1111/ajsp.12332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A. G. , Chang, E. C. , Li, M. , Chang, O. D. , Yu, E. A. , & Hirsch, J. K. (2020). Trauma and suicide risk in college students: Does lack of agency, lack of pathways, or both add to further risk? Social Work, 65(2), 105–113. 10.1093/sw/swaa007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. L. , Lai, K. Y. C. , & Lo, J. W. K. (2017). Perceived social support in Chinese parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a Chinese context: Implications for social work practice. Social Work in Mental Health, 15(1), 28–46. 10.1080/15332985.2016.1159643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Magro, S. W. , Utesch, T. , Dreiskämper, D. , & Wagner, J. (2019). Self‐esteem development in middle childhood: Support for sociometer theory. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(2), 118–127. 10.1177/0165025418802462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mana, A. , Saka, N. , Dahan, O. , Ben‐Simon, A. , & Margalit, M. (2021). Implicit Theories, Social Support, and Hope as Serial Mediators for Predicting Academic Self‐Efficacy Among Higher Education Students. Learning Disability Quarterly, Advance online publication. 10.1177/0731948720918821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, R. C. , Cheng, H. L. , Wong, J. , Booth, N. , Jones, Z. , & Sevig, T. (2017). Hope for help‐seeking: A positive psychology perspective of psychological help‐seeking intentions. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 237–265. 10.1177/0011000017693398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay, F. , Johnson, D. C. , Dimoulas, E. , Morgan, III, C. A. , Charney, D. , & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4(5), 35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M. A. , Stanley, I. H. , & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093–1094. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, E. , & Montemuro, M. (1986). Hope, morale and adaptation in patients with chronic heart failure. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 11(4), 429–438. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1986.tb01270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustøen, T. , Cooper, B. A. , & Miaskowski, C. (2010). The importance of hope as a mediator of psychological distress and life satisfaction in a community sample of cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 33(4), 258–267. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181d6fb61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici, S. A. (2020). Hope and loneliness mediate the association between stress and subjective vitality. Journal of College Student Development, 61(2), 225–239. 10.1353/csd.2020.0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. , Harris, C. , Anderson, J. R. , Holleran, S. A. , Irving, L. M. , Sigmon, S. T. , … Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual‐differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundy, A. , Roskell, C. , Elder, T. , Collett, J. , & Dawes, H. (2016). The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis: A thematic synthesis. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 4(1), 22–47. 10.4236/ojtr.2016.41003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. 10.1177/1094428105284955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani‐Aidan, Y. , Melkman, E. , & Hellman, C. M. (2019). Nurturing the hope of youth in care: The contribution of mentoring. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(2), 134. 10.1037/ort0000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teneva, N. , & Lemay, E. P. (2020). Projecting loneliness into the past and future: Implications for self‐esteem and affect. Motivation and Emotion, 44(5), 772–784. 10.1007/s11031-020-09842-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UK Government . (2018). A connected society: A strategy for tackling loneliness–laying the foundations for change. HM Government. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/750909/6.4882_DCMS_Loneliness_Strategy_web_Update.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UK Government . (2020). UK government loneliness annual report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/loneliness‐annual‐report‐the‐first‐year/loneliness‐annual‐report‐january‐2020–2 [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: The moderating impact of social support among social work students. Advances in Social Work, 9(2), 106–125. 10.18060/51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zee, K. S. , Bolger, N. , & Higgins, E. T. (In press). Regulatory effectiveness of social support. Journal of personality and social psychology. 10.1037/pspi0000235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. (2017). The stress‐buffering effect of self‐disclosure on Facebook: An examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 527–537. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W. , Wang, C. D. , & Chong, C. C. (2016). Adult attachment, perceived social support, cultural orientation, and depressive symptoms: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(6), 645. 10.1037/cou0000161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G. D. , Dahlem, N. W. , Zimet, S. G. , & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supplementary sensitivity analysis: alternative model.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in ‘OSF’ at DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/Y6QVN.