Significance

The political influence of a group is typically explained in terms of its size, geographic concentration, or the wealth and power of the group’s members. This article introduces another dimension, the penumbra, defined as the set of individuals in the population who are personally familiar with someone in that group. Distinct from the concept of an individual’s social network, penumbra refers to the circle of close contacts and acquaintances of a given social group. Using original panel data, the article provides a systematic study of various groups’ penumbras, focusing on politically relevant characteristics of the penumbras (e.g., size, geographic concentration, sociodemographics). Furthermore, we show the connection between changes in penumbra membership and public attitudes on policies related to the group.

Keywords: social networks, interest groups, political attitudes

Abstract

To explain the political clout of different social groups, traditional accounts typically focus on the group’s size, resources, or commonality and intensity of its members’ interests. We contend that a group’s penumbra—the set of individuals who are personally familiar with people in that group—is another important explanatory factor that merits systematic analysis. To this end, we designed a panel study that allows us to learn about the characteristics of the penumbras of politically relevant groups such as gay people, the unemployed, or recent immigrants. Our study reveals major and systematic differences in the penumbras of various social groups, even ones of similar size. Moreover, we find evidence that entering a group’s penumbra is associated with a change in attitude on group-related policy questions. Taken together, our findings suggest that penumbras are pertinent for understanding variation in the political standing of different groups in society.

Calls for changes to the US immigration system have been a feature of American politics for several decades. In particular, activists have called for granting more visas for immigrants seeking to enter the country as well as for providing undocumented immigrants a path to citizenship. Yet, for years, strikingly little movement has been registered on these matters, either in terms of public opinion or in change of actual policy. In contrast, over the same time period, gay rights have undergone a major transformation in the country, with many states, and later the Supreme Court, recognizing same-sex marriage and with a large share of Americans expressing support for this change. The contrasting experience of these two hitherto socially discriminated groups—immigrants and gay people—raises a key question: what explains variation in the resonance and political standing of different social groups?

Earlier research studying the political influence of social groups has focused either on differences in the groups’ resources or on features that affect their ability to overcome the collective action problem. In particular, large and dispersed groups are considered to face greater difficulties in wielding influence, due to the incentive of each individual member to free ride on the efforts of others (1). Other explanations have focused on the intensity and commonality of interests among the group’s members as key dimensions in its ability to mobilize collectively and yield influence (2–5).

This study introduces a different dimension that we argue is pertinent to understanding the political standing of a social group: its penumbra, which we define as the set of people who have personal familiarity with members of the group, be it as relatives, friends, or acquaintances.* When group members routinely interact with people outside the group, these interactions can facilitate greater understanding of, and sympathy toward, the needs and interests of the group’s members. Moreover, such interactions can reduce fear of and increase tolerance toward members of an out-group.

Perhaps the most widely known articulation of this notion is the intergroup contact hypothesis (6), which holds that extended contact allows for learning about the group, an understanding of its circumstances, and the creation of affective ties with its members. Such changes may also bring about a shift in views toward the group’s members (6–9). Indeed, positive contact experiences have been shown to reduce self-reported prejudice toward a range of socially disadvantaged groups, including Blacks, the elderly, gay men, and the disabled (10–12). Furthermore, research indicates that even unstructured contact can often change attitudes toward group members (8). Contacts with members of an out-group are necessarily positive, and in some instances such interactions could actually deepen apprehension or hostility.† We therefore conjecture that a systematic study of various penumbras can yield meaningful insight into the differences in the political standing of different social groups. Moreover, taking into account changes in individuals’ membership in certain penumbra can help explain shifts in their political attitudes.

Unlike the concept of one’s social network, which refers to the contacts and relationships of a certain individual, a penumbra refers to the circle of close contacts and acquaintances of a given group. For example, two social groups of similarly modest size may have penumbras that vary in crucial ways: a group’s penumbra can be large in size or small, it can be geographically concentrated or dispersed, and it can be composed of mostly rich or poor people. This study is a systematic exploration of this concept and its potential political significance.

The study of penumbras and their political effects is challenging in part because of the lack of comparable data about the people who are familiar with members of various social groups of interest. We know little about the sizes of penumbras or their characteristics. Additionally, even if information on the penumbras was readily available, investigating the impact of membership in the social penumbra of the group on one’s attitude toward the group is difficult because membership in the penumbra is not randomly assigned. People often know members of a social group because they choose to or because they make certain decisions about where they want to live or spend their time (8). These choices then make a person more or less likely to meet members of the core group. This means that the correlation between familiarity with a group’s members and attitudes on issues related to that group does not necessarily reflect a causal relationship. Familiarity may not necessarily be the trigger for a person’s attitude.

In this paper, we report findings from a study designed to better deal with those issues. We carried out a two-wave panel survey in which we asked a national sample of Americans a set of policy questions pertaining to a set of social groups (for example, assistance to the unemployed, same-sex marriage, and immigration restrictions). Later in the survey, we asked questions pertaining to their familiarity with members of these various social groups (for example, gay people, the unemployed, immigrants), probing them about the number of family members, close friends, and acquaintances they know within that group. A year later, we asked the same respondents the same set of questions, thus allowing us to track changes in membership in different penumbras and to investigate the empirical relationship between changes in penumbra status and attitudes on policies related to the relevant social group.

We find wide variation in both the size and the shape of key penumbras for core groups of comparable size. For example, about 3% of the US population identifies as gay or lesbian, about half the share of people with a mortgage “under water” at the time of our survey. Yet, the sizes of penumbras of the two groups go in the opposite direction, with 74% of respondents saying they knew at least one gay person and only 35% reporting that they knew someone whose mortgage is under water. Our analysis indicates that some of this difference could be explained by the fact that the penumbra of underwater mortgages is far more concentrated geographically than the penumbra of gays and lesbians. Yet, the difference may also be due to people’s unawareness of the mortgage status of their friends and acquaintances. Indeed, this is part of our point: if a group such as underwater mortgage holders is hidden to much of the general population, this will affect the extent to which their problem becomes salient and how it is perceived by the public. These differences thus suggest why specific policies such as same-sex marriage and debt forgiveness to mortgage owners, while directly affecting similarly sized groups, could resonate very differently across the broader population.

To assess this link between a group’s penumbra and public attitudes on issues related to the group’s interests, we exploit the panel design of the survey to track changes in familiarity with group members with views on policies related to the group. Indeed, we show evidence that entering a penumbra has in some instances a significant impact on group-related policy preferences (e.g., on gay people, Muslims, National Rifle Association [NRA] members).

Our study makes three contributions. First, it introduces the concept of penumbra as a relevant political characteristic of social groups, shifting the focus from the groups’ members to features of the group’s social circle (i.e., its outward contacts with nongroup members). Second, we provide a set of estimates of the penumbras of an array of different groups in society and highlight the significant variation in the penumbras’ size and characteristics (e.g., in terms of income, education, political leanings). Finally, we provide preliminary evidence regarding the political significance of penumbras, demonstrating that a change in penumbra status is in some cases also associated with shifting views on policy matters related to the group in question.

Data and Empirical Approach

We measure penumbras using a two-wave internet panel survey designed by us and administered by YouGov. Three thousand respondents were interviewed in wave 1 in late August and September 2013; of them, 2,106 were reinterviewed in wave 2 a year later. YouGov aims for a sample of American adults using quota sampling on age, sex, and other demographics. Our wave 1 sample was unweighted, but weights are supplied for wave 2 to help deal with dropout. We report analyses on those respondents who completed both waves. We use survey weights when computing population proportions and averages; we do not use the weights for regression analyses that adjust for demographics.

We asked about penumbra membership in 14 social groups and attitude questions on 12 related policies, with some of the policy questions pertaining to more than one group. The groups include gays and lesbians, recent immigrants, NRA members, unemployed people, individuals currently taking care of an elderly family member, and others (SI Appendix, Table S1). The term social group can refer to very different kinds of aggregations of people. It can designate members of a certain social category that is based on a common attribute (e.g., of a certain age group or income bracket). Other social groups are defined by the interrelatedness of their members (e.g., gays and lesbians, NRA members). The debate over social group classification has been widely explored in the sociological literature (14, 15). For our purposes, it suffices to say that in theory, a penumbra can be of any social group, although penumbras of some groups are likely to be more meaningful than others. We return to the issue of meaningfulness in Discussion.

In selecting the set of social groups for study, we focused on dimensions that the literature indicates are potentially consequential for the impact that penumbra membership might exert on political preferences. These dimensions, cited earlier, include the size of the core group, whether membership of the group is voluntary or not, whether the ascriptive feature of the group is one associated with high or low social status, and whether the group is associated with the liberal or conservative camp. The advantage of exploring penumbras of groups that differ along multiple dimensions comes at a cost that we are unable to systematically assess the impact of a specific dimension that characterizes the core group—for example, whether group membership is voluntary—on the influence of penumbra membership. This is a necessary trade-off given the aims of this study.

Penumbra membership was constructed by asking the respondents to report the number of people from the social group who are 1) close family, 2) close friends, and 3) other people they know. To add clarity, we defined the third category as “people that you know their name and would stop and talk to at least for a moment if you ran into the person on the street or in a shopping mall.” This does not address more tenuous connections such as interactions with strangers or people heard about from the news media, as our focus here is on personal social connections. Finally, we prompted the survey respondents with eight first names and asked them to count the number of people they knew with each name. The addition of names helps us measure the size of each respondents’ social network and also provides a check on the face validity of our estimates regarding the penumbra of the different social groups. We asked about the names Rose, Emily, Bruce, Walter, Tina, and Kyle, chosen to represent a balance of male, female, young, middle aged, and old, along with Jose and Maria to target the Hispanic population.

The policy questions we asked were directly relevant to at least one of the social groups of interest. For example, with respect to the immigrant penumbra, respondents were asked for their views on whether more or fewer immigrants should be permitted to live in the United States. To assess the policy attitudes of the gay penumbra, we asked respondents for their views about gay marriage. To tap into the views associated with knowing a gun owner, we asked all respondents about their position on a nationwide ban on assault weapons. On the eldercare penumbra, we asked about tax breaks for family expenditures on care provision for elderly family members. The exact wording of all of the questions appears in SI Appendix.

To estimate the degree to which social groups differ in the geography of their penumbras, we fit for each group a hierarchical model predicting penumbra membership across the 50 states. We fit the model, i = 1, … , N, where if survey respondent is in the penumbra of group , is an index variable for the state of residence of person , and we are estimating hyperparameters for each group. We fit the model in the Bayesian inference package Stan (16) so as to estimate the proportion of people in the penumbra, for each group and each state.

Results

Key Characteristics of Social Penumbras.

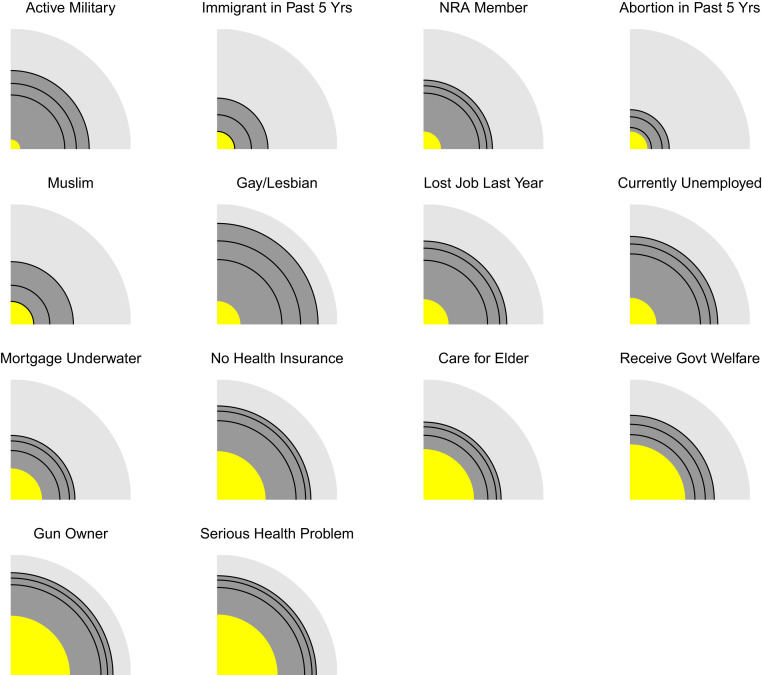

We begin by examining the size of the penumbras of different social groups, as measured by the percentage of respondents who knew at least one person in a group. Fig. 2 illustrates graphically the differences in the size of both the core group (gray inner circles) and that of the penumbra, with concentric circles starting with close family and then extending to include close friends and acquaintances. As the figure makes clear, the penumbra is typically much larger than the core group. For example, less than 1% of American adults are in the active military, but nearly half of respondents know someone in the service.‡The gay/lesbian penumbra is also large in comparison with the size of the core group itself, with nearly three-quarters of respondents reporting that they know someone among this group, which is estimated to comprise about 3 to 4% of the population.

Fig. 2.

Core groups and penumbra size. Groups asked about in our survey in increasing order of size. For each group, the area of the yellow circle indicates its size, and the concentric circles show its estimated penumbra: the percentage of survey respondents who report knowing at least one family member, close friend, or other acquaintance in the group. The light gray concentric circle denotes the rest of the US population that is not in the group’s penumbra.

Fig. 1.

Sketch of the social penumbra of a group in the population.

Yet, such ratios between penumbra and core group are rather unique. At the other extreme, relatively few people report knowing someone who had an abortion in the past 5 y, despite there being millions of women who fall into this category. This is probably due to the fact that women who have had abortions do not always reveal this fact to their acquaintances (17). This variation highlights a broader point: the sizes of penumbras can vary greatly not only due to differences in the size of the core groups themselves but also because of differences in the extent to which group members can be identified or reveal themselves as such (Fig. 2).

The figure also highlights the fact that some groups have a penumbra of a similar size (e.g., gun owners, gays and lesbians, people with serious health problems), but the core groups differ greatly. Gun owners, for example, constitute about 24% of the population, a figure about seven times the number of gays and lesbians in the United States (a group with a similarly sized penumbra).

Another important factor is the core group’s “shape” (i.e., its spatial dispersion). This could account for variation in the size of the penumbra, adjusting for the core group’s size. It could also help explain why some groups have a more geographically dispersed penumbra.

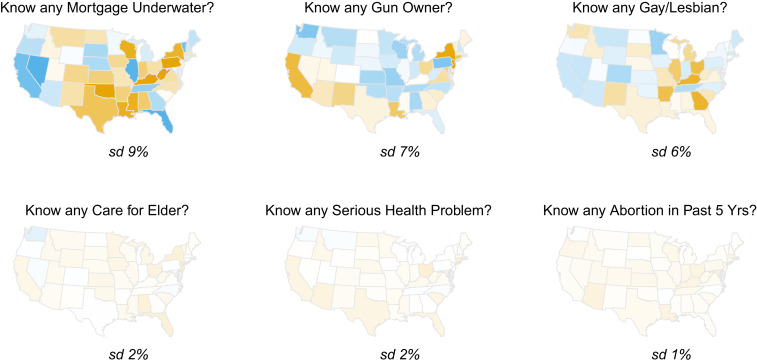

As shown in Fig. 3, some groups such as underwater mortgages, gun owners, and gays and lesbians show a fair degree of geographical concentration in their penumbras. Many people know underwater mortgage owners in the high-delinquency states such as California, Nevada, and Florida, while only a few know members of this group in states that did not experience the real estate bubble, such as Wisconsin or Kentucky. In contrast, penumbras of other social groups such as eldercare, seriously ill, and women who had abortions are essentially uniformly distributed across the country. These maps should be taken as showing general patterns, and particular state estimates can be noisy. We also estimate the SD of these state proportions, as reported in the last column of SI Appendix, Table S1.

Fig. 3.

Maps of the three most geographically dispersed penumbras, followed by three of the least dispersed penumbras for comparison.

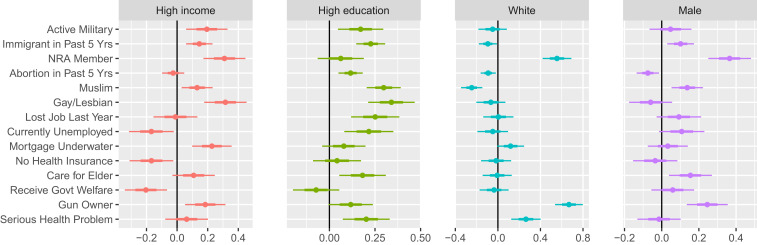

In addition to the variation in size and shape, there are also distinct differences in the socioeconomic characteristics of the different penumbras. Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Table S1 present a comparison of some of the characteristics, such as the prevalence of high-income individuals in each group’s penumbra and the share of Whites and of college-educated individuals. Such differences speak to the likely possibility that who is in the penumbra (e.g., opinion leaders, people with many social ties) matters to the group’s clout and influence. Indeed, as the comparisons of penumbra characteristics indicate, the heterogeneity is substantial. For example, the penumbras of welfare recipients, uninsured people, and unemployed people have the lowest share of upper-income individuals (20% or less) and also the lowest share of college-educated respondents. At the opposite end, the penumbras of NRA members, Muslims, and recent immigrants have a particularly high share of upper-income and well-educated people.

Fig. 4.

Estimated coefficients 2 SEs of regressions of penumbra score on indicators for education, income, sex, and race.

The fact that newly arrived immigrants and Muslims have a highly educated penumbra also corresponds with the fact that the more educated tend to hold substantially more favorable views of immigrants and immigration. It is an open question to what extent that is a causal relationship and in which way causality runs in this case. We return to this issue below by exploring how attitudes toward group-related policies shift with change in penumbra membership.

In sum, social groups—even ones with a similarly sized core—differ greatly in the size and key characteristics of their penumbras. Next, we turn to assess some political repercussions of penumbras and their membership.

Penumbra Membership and Political Attitudes.

We now shift from summarizing the penumbras to studying the views of their members. To what extent does being part of a certain social penumbra affect one’s political attitudes? This section assesses the evidence regarding our contention that social penumbras can help account for systematic variation and change in political attitudes. We begin by exploring two sets of correlations that suggest that penumbra membership is a factor in shaping political affiliations.

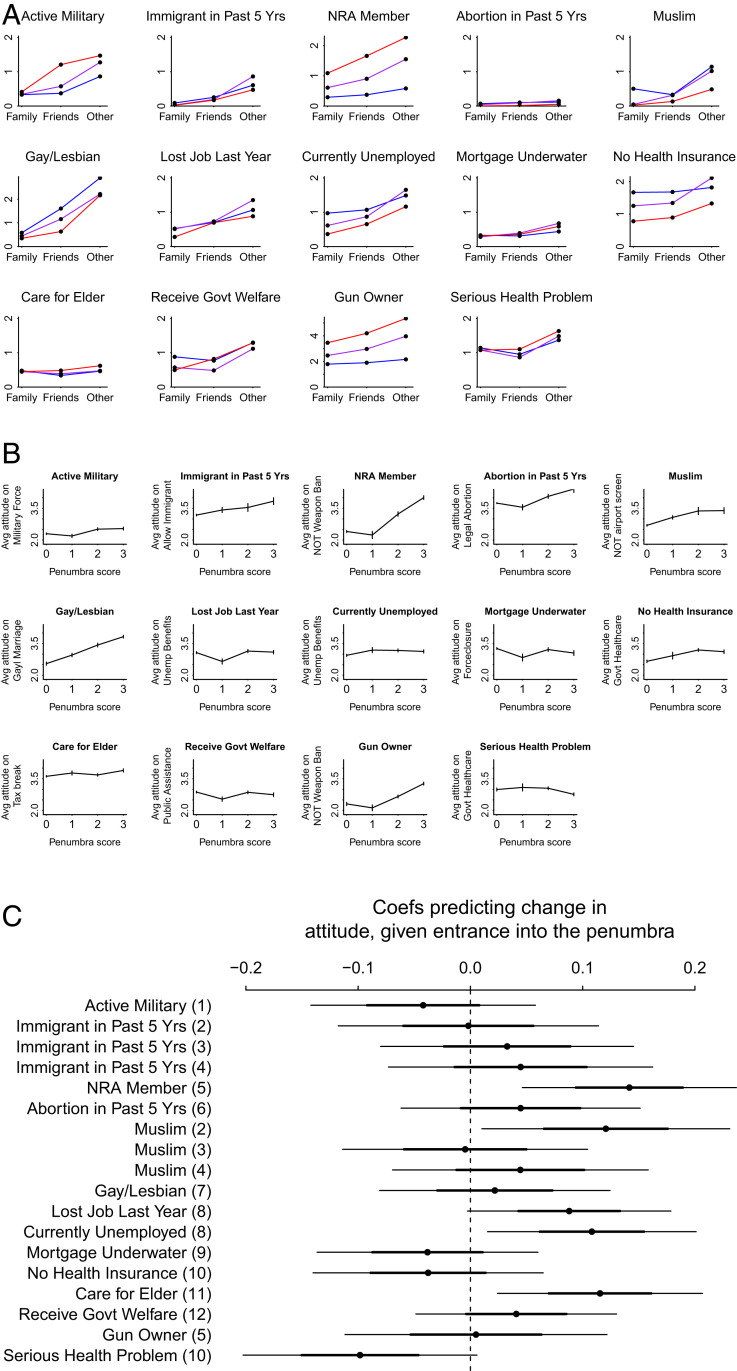

First, we analyze whether social groups differ systematically in terms of the partisan leanings of their penumbra. Fig. 5A shows average penumbra sizes as a function of party identification. Patterns are what one might expect, with Republicans knowing more NRA members and people in the military and Democrats knowing more gays and people with no health insurance. Partisan differences are mostly larger among friends and acquaintances than among close family.

Fig. 5.

Membership in penumbra and political preferences. A presents the average (Avg) number of people known in each group, by party identification (ID) (SI Appendix has the wording of the policy questions). B presents the correlation between membership status in the penumbra and issue attitude on group-related policy. C presents the estimated effect of entering a penumbra during the year on a group-related policy question. The coefficients are obtained from a regression that adjusts for attitude in wave 1 and demographic variables. Numbers in parentheses denote the policy question respondents were asked (SI Appendix has the numbered question list).

Next, we assess the association between penumbra membership and attitudes on policy questions directly related to the social group of interest. Fig. 5B shows the raw correlations of penumbra membership with attitudes on these policy issues. As the figure indicates, the results vary: the correlation between knowing NRA members and opposing a weapon ban or between knowing gay people and supporting same-sex marriage is strong. For other issues, the correlations are lower, and for some, the correlation is zero. Overall, the correlations tend to be larger for social issues and are much smaller (to nonexistent) for attitudes on economic issues such as unemployment benefits, mortgage foreclosures, tax breaks for caregivers, and public assistance.

This pattern is consistent with a range of findings in the study of American politics and public opinion, which finds that attitudes on economic issues are strongly aligned with partisanship and political ideology (18, 19). Hence, it makes sense that personal contacts are less important, as compared with one’s ideology, in predicting economic attitudes. That said, we still find it surprising that there is zero correlation between knowing someone with an underwater mortgage and supporting mortgage relief or between knowing someone with serious health problems and views on health care spending.

It is difficult to interpret static correlations between penumbra membership and policy attitudes. We therefore seek to get more leverage on causality by exploiting the panel aspect of our study, examining changes in attitude that occur following changes in penumbra status. So, for each of our group penumbras and for each corresponding political issue question, we run a regression predicting change in issue attitude, given change in penumbra status. In the regression, we also adjust for attitude at wave 1 and key demographic and political background variables.

Our interest is in measuring the effect on issue attitudes of entering the penumbra. Hence, we restrict the sample to respondents who were not in the penumbra in wave 1. A change in penumbra status can arise in several ways. A person may for the first time meet and befriend someone who is a member of the core group. Alternatively, a friend can change status and become a new member of the core group (e.g., is laid off), thereby rendering their social circle part of the penumbra of unemployed people. Alternatively, that friend may have been a member of that core group all along but only later revealed as such (e.g., a gay person coming out of the closet), or the respondent can be led into a penumbra due to personal circumstances (e.g., an economic reversal resulting both in meeting an unemployed person and in changing their view on relevant policy issues). Finally, personal or external events may make a certain core group salient and thus, lead people to notice that they are part of that group’s penumbra (e.g., a court ruling on women’s right to choose making it salient that a friend had had an abortion in the past). Thus, entry into the penumbra is not randomly assigned. Our identifying assumption, however, is that penumbra entry in a given period is orthogonal to the propensity to change attitude on the relevant policy question during that same time period. In many instances, although surely not in all, this seems to be a plausible assumption. For example, there is little reason to expect that people with a propensity to enter the eldercare penumbra in the coming year are more likely to change their attitudes on tax breaks for eldercare, other than through the penumbra entry itself.

Fig. 5C shows the results. The scale tells us that the estimated effect for each penumbra/issue combination is small. On average, we see a positive effect (the issues have been aligned so that we expect to see a positive coefficient in each case) of about 0.05, consistent with entrance to the penumbra having a 5% chance of shifting a respondent by one point on the one to five scale. The wide CIs indicate uncertainty about the relative magnitudes and even the signs of the effects of entering different penumbras. The groups for which the coefficients seem most clearly positive are NRA members (and attitudes toward bans on guns), the Muslim penumbra (and opposition to airport screening), currently unemployed (and attitudes on unemployment insurance benefits), and elderly care penumbra (and support for tax breaks for caregivers).

Considering all of the estimates in Fig. 5C together, there is no evidence that any of the effects are negative; rather, it appears that there are small average effects of entering the penumbra, but with available data, one cannot reliably identify which effects are larger than others.

To address four possible threats to identification, we perform placebo checks: 1) refitting our model in time-reversed order to address the possibility that the results are artifacts of measurement error, 2) permuting issue questions while maintaining their ideological direction to address the possibility that we are just capturing general liberal–conservative ideology, 3) repeating our analysis using different measures of penumbra membership and considering different interactions and data-exclusion rules, and 4) comparing with self-perceived changes in positions as a test for demand effects. As we discuss in SI Appendix, the results from the robustness checks support our main claims.

Discussion

Being in a group’s penumbra tends to be positively correlated with positive attitudes on related political issues, but these correlations are high only for some of the groups we have studied. Using our panel study, we estimate that these correlations represent, at least in part, a causal relationship. Overall, we estimate that entering a group’s penumbra has a small but positive effect on attitudes on related political questions. It is quite likely that the change in attitudes occurs over a longer period than we have examined in our panel, in which case our analysis represents a floor estimate of the true effect of entering a penumbra.

It is also possible that the largest effect of entering a penumbra is to increase the salience of certain issues rather than to directly change attitudes. In this case, groups’ resonance in society may increase when its penumbra grows, without public opinion shifting in favor of group-related policies. For example, that Muslims have become a widely discussed social group in many Western countries may mean that more people become aware when their acquaintances are Muslim, and its penumbra would grow. Even so, this larger penumbra would not necessarily lead to a more pro-Muslim stance in society as a whole: either because members of the penumbra will not become more pro-Muslim or because this shift would be offset by shifts among those outside the Muslim penumbra. Similarly, there is debate within the prochoice community as to the potential political effects of more women revealing their abortion histories to their larger social networks. Further research is needed on the conditions under which changes in the penumbra are likely to translate into more favorable outcomes and political influence for a group.

The dramatic increase in the use and membership of online social network platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) may also have important implications for the penumbras of social groups. Specifically, penumbras may now include people who have no personal contact with a member of the core group but nonetheless, follow a member online and come to feel close to that individual, even without personal acquaintance. Similarly, our study does not track second-degree membership, such as friends of friends, in penumbras. Thus, future research should examine whether and how indirect and online contacts influence the penumbras that people effectively feel a part of.

Conclusion

This study calls for considering penumbras when analyzing the social and politically relevant characteristics of groups in society. By providing measurements of key characteristics of a wide range of penumbras and demonstrating their potential relevance for explaining policy attitudes—and in some cases, attitude change—we hope to have advanced this objective. Indeed, we conjecture that penumbras can help account for a wide array of other phenomena, ranging from intergroup relations to variation in media attention to certain events and from fundraising success to the formation of political coalitions. The present study hopefully lays the foundation for future work on these important issues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank two reviewers, Yuling Yao, and Sarah Cowan for helpful discussions and the US NSF for financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*The term penumbra is used during a solar eclipse to describe the surrounding shades circling the dark shadow of the moon. Analogously, we consider the penumbra of the core social group to be the equivalent of the degrees of shadow (Fig. 1).

†Even when the contact is positive and associated with decreased hostility toward the members of the out-group, the interaction need not lead to a change in views on policies pertaining to the out-group. For example, ref. 13 found that following positive contact, the affective reactions of Whites toward Blacks had changed, but no change was registered in White subjects’ attitudes on policies geared toward combating racial inequality in areas such as housing, jobs, or education.

‡This figure represents some combination of knowing people through one’s social network as well as uncertainty about classification; for example, one might count a friend who is no longer in active service, and this would be part of the calculation of the penumbra but not in the group size.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2019375118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Anonymized (Stata, SPSS, and R files) data have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/kjeh2/).

References

- 1.Olson M., The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Harvard University Press, 1965). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Offe C., Wiesenthal H., Two logics of collective action: Theoretical notes on social class and organizational form. Polit. Power Soc. Theor. 1, 67–115 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman G. M., Helpman E., Special Interest Politics (MIT Press, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verba S., Schlozman K. L., Brady H. E., Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlozman K. L., Verba S., Brady H. E., The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allport G. W., The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, 1954). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams J., Robin M., The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions: A Survey of Research on Problems of Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Group Relations (Social Science Research Council, 1947). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettigrew T. F., Tropp L. R., A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazer D., Rubineau B., Chetkovich C., Katz N., Neblo M., The coevolution of networks and political attitudes. Polit. Commun. 27, 248–274 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Works E., The prejudice-interaction hypothesis from the point of view of the negro minority group. Am. J. Sociol. 67, 47–52 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspi A., Contact hypothesis and inter-age attitudes: A field study of cross-age contact. Soc. Psychol. Q. 47, 74–80 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuker H. E., Hurley M. K., Contact with and attitudes toward persons with disabilities: The measurement of intergroup contact. Rehabil. Psychol. 32, 145–154 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackman M. R., Crane M., ‘Some of my best friends are black : Interracial friendship and whites’ racial attitudes. Publ. Opin. Q. 50, 459–486 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajfel H. E., Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (Academic Press, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner J. C., “Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group” in Social Identity and Intergroup Relations, H. Tajfel, Ed. (European Studies in Social Psychoology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1982), pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stan Development Team , Stan modeling language users guide and reference manual, Version 2.25. https://mc-stan.org. Accessed 22 January 2021.

- 17.Cowan S. K., Secrets and misperceptions: The creation of self-fulfilling illusions. Sociological Sci. 1, 466–492 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartels L. M., Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Polit. Behav. 24, 117–150 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margalit Y., Explaining social policy preferences: Evidence from the great recession. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 80–103 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized (Stata, SPSS, and R files) data have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/kjeh2/).