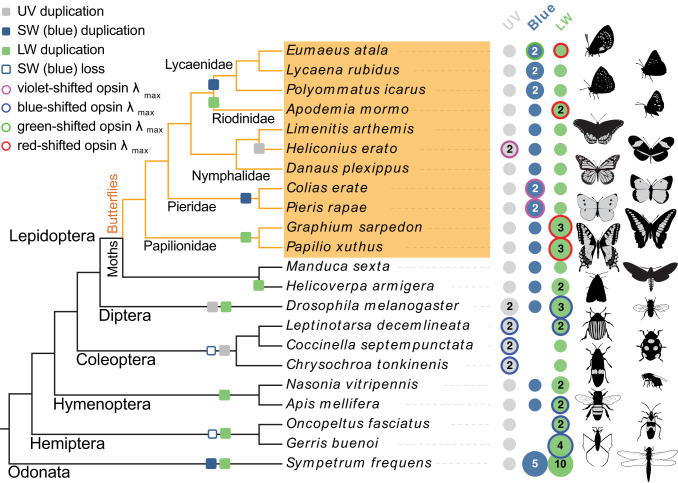

Fig. 1.

Visual opsin gene evolution and spectral tuning mechanisms in insects. Visual opsin genes of the Atala hairstreak (E. atala, Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) in comparison with those encoded in the genomes of diverse insects. The opsin types are highlighted in gray for UV, in blue for short wavelength (SW), and in green for long wavelength (LW). Numbers indicate multiple opsins, whereas no dot indicates gene loss. Colored circles indicate instances of shifted spectral sensitivities in at least one of the encoded opsins. The direction of shift is inferred from the opsin lambda max that departs from the typical range of absorbance in the opsin subfamily using wavelength boundaries for the various colors: UV <380 nm, violet 380 to 435 nm, blue 435 to 492 nm, green 492 to 530 nm, and red shifted >530 nm. Coleopteran lineages, and some hemipterans, lost the blue opsin locus and compensated for the loss of blue sensitivity via UV and/or LW gene duplications across lineages (11, 12). In butterflies, extended photosensitivity at short wavelengths is observed in Heliconius erato with two UV opsins at λmax = 355 nm and 398 nm (10) and in P. rapae with two blue opsins with λmax = 420 and 450 nm (17). A blue opsin duplication occurred independently in lycaenid butterflies (61). LW opsin duplications occurred independently in most major insect lineages (6, 16, 55) and confer a variable range of LW sensitivities with or without additional contributions from lateral filtering. In order to extend spectral sensitivity at longer wavelengths while sharpening blue acuity, some lycaenid butterflies have evolved a new color vision mechanism combining spectral shifts at a duplicate blue opsin and at the LW opsin. Images credit: Christopher Adams (illustrator).