Abstract

Emerging evidence revealed that circular RNAs (circRNAs) play significant roles in regulating tumorigenesis and cancer progression. However, few circRNAs were well characterized in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). We found that circPVT1 was significantly upregulated in ccRCC tissues and positively associated with the clinical stage. The Area Under Curve of tissue and serum circPVT1 expression in ccRCC were 0.93 and 0.86, respectively. Importantly, we demonstrated that circPVT1 promoted ccRCC growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. We also found that circPVT1 directly binds to miRNA‐145‐5p via the Biotin‐labelled miRNA pulldown assay and dual‐luciferase reporter assay, and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor significantly attenuated the effect of circPVT1 knockdown on ccRCC cells. Moreover, through RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis, we demonstrated that TBX15 was regulated by the circPVT1/miR‐145‐5p axis and predicted poor prognosis in ccRCC. These findings suggest that circPVT1 promotes ccRCC growth and metastasis through sponging miR‐145‐5p and regulating downstream target TBX15 expression. The circPVT1/miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis might be a potential diagnostic marker and therapeutic target in ccRCC.

Keywords: ccRCC, circPVT1, invasion, miR‐145‐5p, proliferation

We identified an oncogenic circular RNA circPVT1, which was overexpressed in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) tissues and promoted the growth and metastasis of ccRCC in vivo and in vitro. circPVT1 directly bound to miR‐145‐5p and subsequently inhibited its suppressing capability on TBX15. Our study highlighted the regulatory role of the circPVT1/miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis in ccRCC and provided a novel potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for ccRCC patients.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide and is often asymptomatic in an early stage. 1 , 2 Clear cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most common histological type and accounts for about 75% of RCCs. 3 As ccRCC is insensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, surgical resection is considered the best treatment for ccRCC patients. However, about 30% of localized ccRCC patients receiving surgical treatment subsequently developed metastatic disease that proved to be fatal. 4 Despite continued efforts, the mechanisms of ccRCC progression remained largely unknown. Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in ccRCC progression and the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets are in urgent need. The discovery of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) is a great breakthrough in scientific research. 5 , 6 Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a new subtype of ncRNAs with neither 5′ to 3′ polarity nor a polyadenylated tail. Emerging evidence revealed that the dysregulation of circRNAs may be involved in the development and progression of many cancers, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 circRNAs possess the characteristics of high stability, high conservation, and cell or tissue specificity, suggesting their potential applications as biomarkers or therapeutic targets. 11 Recent studies also revealed that circRNAs could serve as competing endogenous RNA by competitively binding to microRNAs’ (miRNA) response elements to regulate gene expression. 12 , 13 circPRKCI, which is highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma, promotes tumor growth in lung adenocarcinoma through the miR‐545/589‐E2F7 axis. 14 circRNA MTO1 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by acting as the sponge of miR‐9. 15 circRNA LARP4 inhibits gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by sponging miR‐424‐5p. 16 However, there is little research on the role of circRNAs in ccRCC progression. In this study, we found that circPVT1 was significantly upregulated in ccRCC tissues and positively associated with the clinical stage. Tissue and serum circPVT1 expression might be a potential diagnostic marker in ccRCC with an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.93 and 0.86, respectively. Loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function revealed that circPVT1 promoted proliferation, migration, and invasion in ccRCC cells. Our in vivo study showed that circPVT1 overexpression significantly promoted ccRCC growth and metastasis. Our mechanism study indicated that circPVT1 functioned as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) and promoted ccRCC progression through directly binding to miR‐145‐5p and regulating TBX15 expression. These results revealed a novel mechanism underlying ccRCC progression and identified circPVT1 as a potential therapeutic target in ccRCC.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Microarray processing

The circRNA expression profiles of ccRCC tissues (seven ccRCC tissues and seven matched adjacent normal tissues) were reanalyzed using circRNA‐sequencing data GSE108735 from GPL20301 platforms. Hierarchical clustering was performed to show the differentially expressed circRNAs with Cluster 3.0 and TreeView software (Stanford University).

2.2. Patients and tissue samples

Ninety matched ccRCC tissues and adjacent normal kidney tissues were obtained from patients who underwent radical or partial nephrectomy at Sun Yat‐sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University. These samples were obtained with informed consent and approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat‐sen Memorial Hospital. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen after surgical removal and stored in RNAlater at −80°C until RNA isolation.

2.3. Cell lines and cell culture

Human RCC cell lines (ACHN, 786‐O and Caki‐1), human normal kidney cell line HK‐2 and human embryonic kidney cell 293T were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). ACHN and 786‐O were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco), Caki‐1 was cultured in McCoy's 5A modified medium (Gibco), HK‐2 was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F‐12 (Gibco), and 293T was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone Technologies) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

2.4. RNA transfection and lentivirus transfection

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) and miRNA mimic transfection were performed with Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. siRNAs and miRNA mimics were obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd (GenePharma). The circPVT1 siRNA target sequences were as follows: Si#1 for circPVT1, 5′‐UGGGCUUGAGGCCUGAUCU‐3′; Si#2 for circPVT1, 5′‐GCUUGAGGCCUGAUCUUUU‐3′. For lentivirus transfection, lentivirus‐mediated circPVT1 overexpression and negative control vector were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen).

2.5. RNA isolation and quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR)

Total RNA of ccRCC tissues and ccRCC cells was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio, Inc). qRT‐PCR was performed with TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara) on a LightCycle 96 Real‐Time PCR instrument (Roche). Relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method, and β‐actin was used as a normalizer. Each qRT‐PCR was performed in triplicate.

2.6. Subcellular fractionation and RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

To determine the cellular location of circPVT1, subcellular fractionation and FISH were performed. For subcellular fractionation, we isolated total RNA from cytosolic and nuclear fractions of ccRCC cells with the PARIS™ Kit (Ambion). For FISH, we directly detected the cellular location of circPVT1 using a Cy3‐labeled probe (GenePharma). 4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain nuclei. Confocal images of the ccRCC cells were captured with a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope system (Leica Microsystems).

2.7. Cell proliferation and transwell assays

For cell proliferation assay, 103 ccRCC cells seeded in a 96‐well plate were tested every 24 hours by CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega) for 5 days. The absorbance value was detected at a wavelength of 490 nm on a multifunctional microplate reader SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices).

For transwell assays, 105 transfected cells were seeded into the upper chamber of transwell chamber inserts with or without precoated Matrigel, and 600 μL medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. After incubating at 37°C and 5% CO2, the cells that migrated or invaded to the lower membrane surface were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet in PBS. The migratory and invasive cells were counted at least in three randomly selected fields. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.8. Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle and apoptosis

Flow cytometry analysis was used to evaluate the role of circPVT1 on the cell cycle and apoptosis of ccRCC cells. For cell cycle assay, at 48 hours after transfection, ccRCC cells were collected, washed with PBS, fixed with 70% ice‐cold ethanol overnight, and stained with propidium iodide (PI). For apoptosis assay, at 48 hours after transfection, ccRCC cells were collected, washed with PBS, and stained with annexin V‐FITC and PI (BD Biosciences). The cell cycle and apoptotic rate of ccRCC cells were detected with a FACSVerse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All experiments were performed independently three times.

2.9. Biotin‐labeled miRNA pulldown assay

To identify the direct binding of circPVT1 and miR‐145‐5p, we performed a biotin‐labeled miRNA pulldown assay. Approximately 107 ACHN and Caki‐1 cells were washed with ice‐cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) three times and lysed in lysis buffer before incubating with biotin‐labeled miRNA. Then, 100 μL streptavidin magnetic beads (Life Technologies) were incubated with the cell lysates overnight at 4°C to pull down the biotin‐labeled RNA complexes. Then, the beads were washed with lysis buffer five times, and the binding RNAs were extracted by Trizol LS (Life Technology) and analyzed by qRT‐PCR.

2.10. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter plasmids psicheck2 with the wild type or mutant sequence of circPVT1 or 3′‐UTR of TBX15 were constructed. 293T cells were seeded into 24‐well plates, transfected with miR‐145‐5p mimics and the luciferase reporter plasmids. After 24 hours of incubation, the firefly and Renilla luciferase activities in each group were detected using the Dual‐luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Renilla luciferase activity was normalized to the luminescence of firefly luciferase in each group. All experiments were performed independently three times.

2.11. Xenograft experiments

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat‐sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat‐sen University (Guangzhou, China). To study the effect of circPVT1 on tumor growth, 5‐week‐old male BALB/c nude mice were randomly divided into a negative group and a circPVT1 overexpression group (5 mice per group). Approximately 5.0 × 106 Caki‐1 cells with stable circPVT1 overexpression or vector were subcutaneously injected into the upper back of the nude mice. Tumor volume (V) was calculated every week with the following formula: V = (W2 × L)/2. Approximately 3.0 × 106 Caki‐1 cells with stable circPVT1 overexpression or vector were intravenously injected into the tail vein of the nude mice. The lung and liver were dissected, embedded in paraffin, and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

2.12. RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

The gene expression profiles of si‐circPVT1 ACHN cells and negative control cells were determined by RNA sequencing. Genes with expression fold change > 2 were identified as differentially expressed and selected for further analysis. CircInteractome (https://circinteractome.nia.nih.gov) was used to screen candidate miRNAs binding to circPVT1. 17 TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org) and MiRPathDB (https://mpd.bioinf.uni‐sb.de) were used to screen potential miR‐145‐5p–regulated genes. 18 GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer‐pku.cn) was used to explore TBX15 expression and clinical prognostic value in ccRCC. 19

2.13. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

ccRCC tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5‐μm sections, and processed for IHC. Sections were incubated with a primary antibody specific for TBX15 (1:200, NBP2‐83624, Novus) overnight at 4°C. A Nikon Eclipse 80i system (Nikon) was used to capture the images, and five fields of view of each slide were detected. The expression of target proteins was assessed by the proportions and intensities of positive cells.

2.14. Western blot analysis

Proteins of ccRCC cells and tissues were extracted in RIPA buffer with proteinase and phosphatase. Identical quantities of proteins were electrophoresed by 10% SDS‐PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, blocked in 5% BSA, and incubated with primary antibodies specific for TBX15 overnight at 4°C. The next day, the membranes were washed three times with Tris Buffered saline Tween (TBST) followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature and washing by TBST for another three times. Finally, the signals were examined using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Merck Millipore) by a molecular imager system (Bio‐Rad Laboratories).

2.15. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed with SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc) and GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software). Student's t‐tests or one‐way ANOVA was used to analyze the difference between groups. The Kaplan‐Meier method and log‐rank test were used to analyzed overall survival rates. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the diagnostic value of circPVT1 expression. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CircPVT1 is overexpressed in ccRCC tissues and cell lines

We analyzed the circRNA expression profiles in ccRCC tissues (seven ccRCC tissues and seven adjacent normal tissues) using circRNA‐sequencing data GSE108735. The heat map was performed to show the top 100 upregulated and downregulated circRNAs in ccRCC tissues (Figure 1A). Among these differentially expressed circRNAs, circPVT1 (hsa_circ_0001821) was significantly upregulated in ccRCC tissues with a fold change of 7.59 and P‐value < .01 (Figure 1B). circPVT1, whose spliced mature sequence length is 410 bp, is derived from exon 3 of the PVT1 gene (chr8: 128902834‐128903244) (Figure 1C). First, we validated circPVT1 in ccRCC cells by Sanger sequencing, which showed the circPVT1 junction sequences were completely in accordance with circBase (Figure 1D). Then, we examined the stability and localization of circPVT1 in the ccRCC cell. The result showed that circPVT1 was resistant to RNase R in ccRCC cell lines (Caki‐1 and ACHN), indicating that circPVT1 had a circular structure in ccRCC (Figure 1E). RNA FISH was performed, and confocal microscopy was used to detect the localization of circPVT1 in the ccRCC cells Caki‐1 and ACHN. The results revealed that circPVT1 was located in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of ccRCC cells (Figure 1F). Subcellular fractionation and qRT‐PCR were performed to confirm the RNA FISH result (Figure 1G). Then, we compared the chromosome interval containing circPVT1 between ccRCC tissues and normal tissues in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. The result showed that circPVT1 was significantly upregulated in ccRCC tissues (n = 448) compared with normal tissues (n = 67) (P < .001) (Figure 1H). The detailed patient characteristics were described in Tables S1 and S2. Next, we designed divergent primers and detected circPVT1 expression in 90 paired ccRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues using qRT‐PCR. The result revealed that circPVT1 was overexpressed in ccRCC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues (P < .001) (Figure 1I). Then, we detected circPVT1 expression in ccRCC cell lines (Caki‐1, ACHN and 786‐O) and normal kidney cells (HK‐2). The result revealed that circPVT1 expression was significantly higher in ccRCC cell lines than in HK‐2 (P < .01) (Figure 1J).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization and expression of circPVT1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A, Heat map for differentially expressed circular RNAs (circRNAs) in seven pairs of ccRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues from GSE108735. B, Relative expression of circPVT1 in ccRCC tissues (n = 7) and adjacent normal tissues (n = 7) from GSE108735. C, Schematic illustration of circPVT1 produced from exon 3 of PVT1 gene. D, circPVT1 junction site in circBase was validated by Sanger sequencing. E, circPVT1 is resistant to RNase R in ccRCC cell lines. F, RNA FISH was performed and confocal microscopy was used to detect the localization of circPVT1 in the ccRCC cells. G, Subcellular fractionation and qRT‐PCR were performed to detect the localization of circPVT1 in ccRCC cells. H, Expression of chromosome interval containing circPVT1 between ccRCC tissues (n = 448) and normal tissues (n = 67) in TCGA database. I, Expression of circPVT1 in 90 ccRCC tissues and 90 adjacent normal tissues quantified by qRT‐PCR. J, Expression of circPVT1 in ccRCC cell lines quantified by qRT‐PCR. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

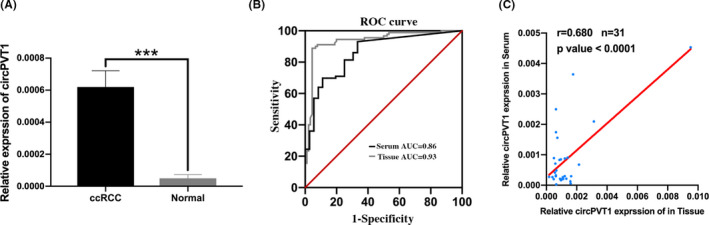

3.2. Diagnostic value of circPVT1 for ccRCC patients

In order to evaluate the diagnostic value of circPVT1 in ccRCC, ROC curve analysis was performed. First, we assessed the diagnostic value of tissue circPVT1 expression, and the result showed that the AUC was 0.93 (Figure 2B). Then, we extracted total RNA from serum samples of 60 ccRCC patients and 40 healthy volunteers and examined the diagnostic value of serum circPVT1 expression. The result showed that serum circPVT1 expression was significantly higher in ccRCC patients than in healthy volunteers (P < .01) (Figure 2A). ROC curve was used, and the AUC was 0.86 (Figure 2B). The detailed patient characteristics whose sera were used are described in Table 2. We found that serum circPVT1 expression was positively associated with T stage (P < .05). Moreover, a positive correlation between the serum and paired tissue expression of circPVT1 in ccRCC patients was determined by the Pearson correlation coefficients (r = .680, n = 31, P < .001) (Figure 2C). These results indicated that circPVT1 might be an effective marker for ccRCC diagnosis.

FIGURE 2.

Diagnostic value of circPVT1 for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) patients. A, circPVT1 expression in serum samples of 60 ccRCC patients and 40 healthy volunteers quantified by qRT‐PCR. B, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of tissue circPVT1 and serum circPVT1 expression to distinguish ccRCC from normal controls. C, The correlation between 31 serum and paired tissue expressions of circPVT1 of ccRCC patients was determined by Pearson correlation coefficients (r = .680, n = 31, P < .001). ***P < .001

TABLE 2.

Correlation between the serum expression levels of circPVT1 and clinical characteristics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) patients

| Characteristics | No. of patients | Expression (circPVT1) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 38 | 0.00067 | .742 |

| Female | 22 | 0.00059 | |

| Age (y) | |||

| <60 | 39 | 0.00074 | .211 |

| ≥60 | 21 | 0.00046 | |

| T stage | |||

| T1‐2 | 53 | 0.00056 | .033* |

| T3‐4 | 7 | 0.00125 | |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | 58 | 0.00063 | .709 |

| M1 | 2 | 0.00086 | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 57 | 0.00064 | .795 |

| N1 | 3 | 0.00076 | |

P < .05.

3.3. circPVT1 expression associated with clinical characteristics of ccRCC patients

We analyzed the association between circPVT1 expression and clinical characteristics of ccRCC patients. We found that circPVT1 expression was positively associated with T stage (P < .001), N stage (P = .0015), and M stage (P < .001), but not associated with other clinical features, including age and gender (Table 1). These results suggested that circPVT1 might be involved in the progression of ccRCC and might be a potential biomarker for ccRCC patients.

TABLE 1.

Correlation between circPVT1 expression and clinical characteristics of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) patients

| Characteristics | Number | Expression | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 58 | 0.00137 | .4839 |

| Female | 32 | 0.00121 | |

| Age | |||

| >60 | 59 | 0.00146 | .1006 |

| <60 | 31 | 0.00167 | |

| T stage | |||

| T1‐2 | 74 | 0.00113 | <.001*** |

| T3‐4 | 16 | 0.00212 | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 84 | 0.00122 | .0015** |

| N1 | 6 | 0.00256 | |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | 82 | 0.00117 | <.001*** |

| M1 | 8 | 0.00285 | |

P < .01.

P < .001.

3.4. circPVT1 knockdown suppressed proliferation and induced cell cycle arrest in ccRCC cells

To investigate the biological function of circPVT1 in ccRCC, siRNAs specifically targeting at junction site were designed to downregulate circPVT1 expression in ccRCC cells. The results showed that circPVT1 expression was successfully knocked down in ccRCC cells, and lncRNA PVT1 had no significant changes (Figure 3A). Then, we performed the MTS assay and EdU assay to evaluate the role of circPVT1 on the proliferation of ccRCC cells. The results revealed that circPVT1 knockdown significantly reduced the proliferation ability in ccRCC cells (Caki‐1, ACHN, and 786O) (Figure 3B,C). To better understand the regulatory role of circPVT1 on the proliferation of ccRCC cells, we performed cell cycle and cell apoptosis analysis using flow cytometry. Cell cycle analysis revealed that cells at G1 phase were significantly increased in the si‐circPVT1 group compared with the negative control (Caki‐1, ACHN, and 786O) (Figure 3D). Cell apoptosis assay showed no significant difference between the si‐circPVT1 group and negative control.

FIGURE 3.

circPVT1 knockdown suppressed the proliferative and invasive phenotype in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cell lines. A, Quantification of circPVT1 expression assessed by qRT‐PCR in ccRCC cell lines treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control. B, MTS assay was performed to detect the proliferation of ccRCC cell lines treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control. C, Edu assay was performed to detect the proliferation of ccRCC cell lines treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control. Representative images and quantification results are shown. D, Cell cycle of ccRCC cell lines treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control was assessed by flow cytometry analysis. Quantification results are shown. E, Representative images and quantification results of cell migration and invasion of ccRCC cell lines treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

3.5. circPVT1 knockdown suppressed migration and invasion in ccRCC cells

In order to investigate the effect of circPVT1 on migration and invasion of ccRCC cells, we performed transwell migration and invasion assays. Migration assay revealed that the number of migratory cells was significantly decreased in the si‐circPVT1 group compared with the negative control. A similar result was observed in invasion assay using Matrigel‐coated chambers. These results indicated that circPVT1 knockdown suppressed migration and invasion in ccRCC cells (Caki‐1, ACHN, and 786O) (Figure 3E).

3.6. circPVT1 overexpression promoted aggressive behavior of ccRCC cells

To further investigate the significant role of circPVT1 in ccRCC, ACHN and Caki‐1 were transfected with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector and negative control. circPVT1 expression was significantly upregulated in ACHN and Caki‐1 after transfection with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector (Figure 4A). Cell proliferation assay revealed that circPVT1 overexpression significantly increased the proliferative abilities of ACHN and Caki‐1 (Figure 4B). Transwell assays revealed that the number of migratory and invasive cells was significantly increased in circPVT1 overexpression ccRCC cells compared with the negative control (Figure 4C,D).

FIGURE 4.

circPVT1 overexpression promoted the proliferation and invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) in vitro and in vivo. A, Representative images of quantification results of ccRCC cells transfected with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector and negative control. B, MTS assay was performed to assess the proliferation ability of ccRCC cells transfected with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector and negative control. C, Transwell migration assay was performed to detect the migratory ability of ccRCC cells transfected with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector and negative control. D, Transwell invasion assay was performed to detect the invasive ability of ccRCC cells transfected with circPVT1‐overexpressing vector and negative control. E, Xenograft tumor models showed that circPVT1 overexpression promoted ccRCC growth in vivo. F, Analysis of tumor weight in the circPVT1 overexpression group and negative control group (n = 5). G, Analysis of tumor volume in the circPVT1 overexpression group and negative control group (n = 5). H, Hematogenous metastasis model showed that circPVT1 overexpression promoted ccRCC metastasis in vivo. I, Analysis of tumor number in the circPVT1 overexpression group and negative control group (n = 5). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

3.7. circPVT1 overexpression promoted growth and metastasis of ccRCC in vivo

In order to investigate the role of circPVT1 in vivo, we constructed Caki‐1 cells with stable circPVT1 overexpression or negative control and then subcutaneously implanted them into nude mice. The weights and volume of the tumors were measured every week. Four weeks after injection, circPVT1 overexpression dramatically increased the tumor weights compared with the negative control (Figure 4E,F). The result also revealed that the tumor volume of the circPVT1 overexpression group was larger than that of the negative control (Figure 4G). Then, we injected Caki‐1 cells with vector or circPVT1 overexpression into nude mice via the tail vein. Six weeks after injection, the nude mice in the vector group developed more visible nodes in the liver than the nude mice in the circPVT1 overexpression group (Figure 4H). Moreover, H&E staining revealed that circPVT1 overexpression dramatically increased the number and size of liver metastatic nodes (Figure 4I). These results showed that circPVT1 overexpression promoted the growth and metastasis of ccRCC.

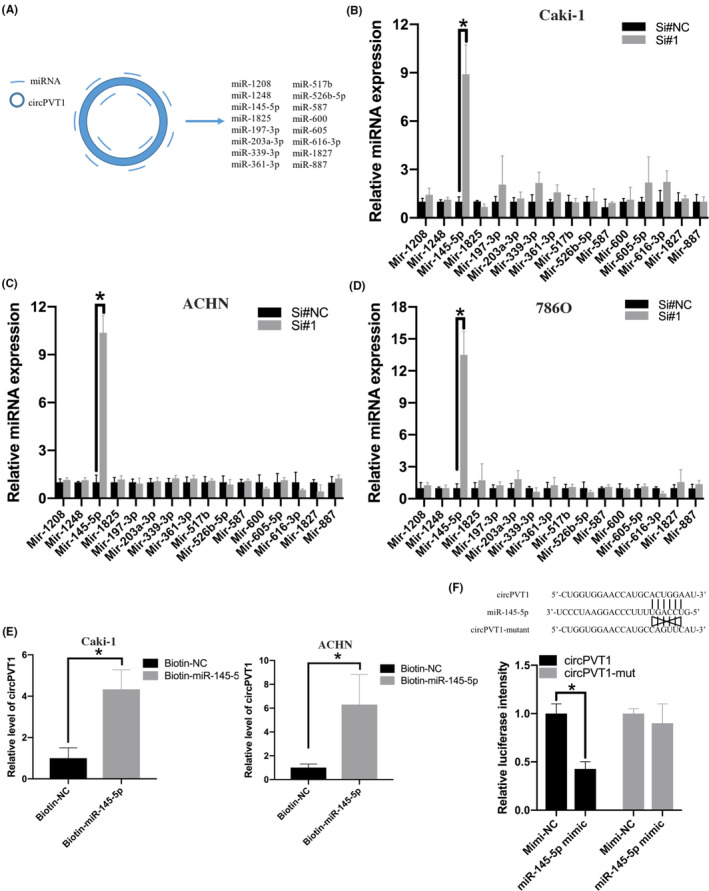

3.8. circPVT1 directly binds to miR‐145‐5p

Emerging evidence reveals that circRNAs could function as miRNA sponges in cancers. In order to explore whether circPVT1 could serve as a sponge for miRNAs in ccRCC, we screened candidate miRNAs using a bioinformatics tool CircInteractome. It showed that circPVT1 could bind to 16 miRNAs according to the complementary sequence (Figure 5A). Subsequently, RNA interference assays revealed that, among these candidate miRNAs, miR‐145‐5p expression was significantly upregulated after circPVT1 knockdown in ccRCC cells (Caki‐1, ACHN, and 786O) (Figure 5B‐D and Figure S1). Then, we focused on miR‐145‐5p and performed biotin‐labeled miRNA pulldown assay to further confirm the direct binding of circPVT1 and miR‐145‐5p. The result showed that circPVT1 was abundantly pulled down by biotin‐labeled miR‐145‐5p in ccRCC cells compared with biotin‐labeled negative control (Figure 5E). To further confirm these results, we performed a dual‐luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase reporter and miRNA mimics were cotransfected into 293T cells. The result showed that the luciferase intensity of 293T cells cotransfected with circPVT1‐wt and miR‐145‐5p mimics significantly reduced, while the luciferase intensity of 293T cells transfected with circPVT1‐mut or miRNA mimics showed no significant changes (Figure 5F). These results demonstrated that circPVT1 directly binds to miR‐145‐5p in ccRCC cells.

FIGURE 5.

circPVT1 directly binds to miR‐145‐5p. A, A bioinformatics tool CircInteractome was used to predict miRNA targets of circPVT1. B‐D, Relative miRNA expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cell line treated with si‐circPVT1 or negative control. E, Biotin‐labeled miRNA pulldown assay was performed to detect the direct binding of circPVT1 and miR‐145‐5p in ccRCC cell lines. F, 293T cell was cotransfected with circPVT1‐wt or circPVT1‐mut with miR‐145‐5p mimic. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

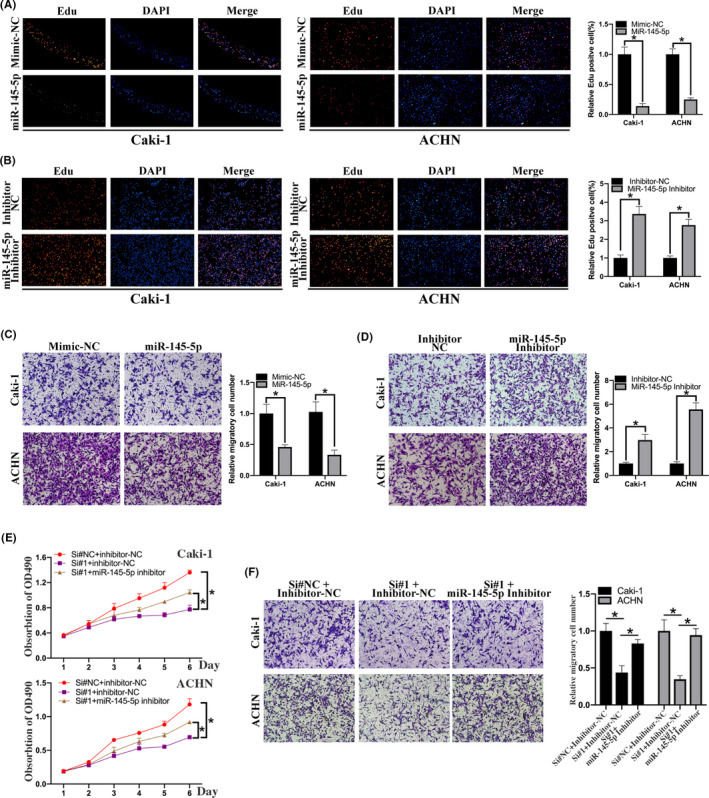

3.9. MiR‐145‐5p inhibitor attenuated the effect of circPVT1 knockdown on ccRCC cells

To further demonstrate that the circPVT1/mir‐145‐5p axis promotes the progression of ccRCC, we first transfected miR‐145‐5p or miR‐145‐5p inhibitor into ccRCC cells. Proliferation assay and transwell assay were performed to investigate the effect of miR‐145‐5p mimics or miR‐145‐5p inhibitor on the proliferative and invasive ability of ccRCC cells. EdU assay revealed that miR‐145‐5p mimics could inhibit the proliferative ability of ccRCC cells, and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor could promote the proliferative ability of ccRCC cells (Figure 6A,B). Transwell assays revealed that miR‐145‐5p mimics could inhibit the migratory ability of ccRCC cells, and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor could promote the migratory ability of ccRCC cells (Figure 6C,D). Then, we cotransfected miR‐145‐5p inhibitor/inhibitor‐negative control (NC) and si‐circPVT1/si‐NC into ccRCC cells. Cell proliferation assay revealed that miR‐145‐5p inhibitor could attenuate the effect of circPVT1 knockdown on the proliferative ability of ccRCC cells (Figure 6E). Transwell assays revealed that miR‐145‐5p inhibitor could attenuate the effect of circPVT1 knockdown on the migratory ability of ccRCC cells (Figure 6F). Taken together, these results suggested that the oncogenic effects of circPVT1 on ccRCC are partially dependent on miR‐145‐5p.

FIGURE 6.

miR‐145‐5p inhibitor attenuated the effect of circPVT1 knockdown on clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cells. A, Edu assay was performed to detect the proliferation of ccRCC cell lines treated with mimic‐NC or miR‐145‐5p mimic. B, Edu assay was performed to detect the proliferation of ccRCC cell lines treated with inhibitor‐NC and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor. C, Transwell assay was performed to detect the migratory ability of ccRCC cell lines treated with mimic‐NC or miR‐145‐5p mimic. D, Transwell assay was performed to detect the migratory ability of ccRCC cell lines treated with inhibitor‐NC and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor. E, MTS assay was performed to detect the proliferative effect of miR‐145‐5p on circPVT1‐knockdown ccRCC cells. F, Transwell assay was performed to detect the migratory effect of miR‐145‐5p on circPVT1‐knockdown ccRCC cells. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

3.10. circPVT1 regulate the miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis in ccRCC

Then, we aimed to found out the target genes circPVT1 regulated through miR‐145‐5p in ccRCC. We performed RNA‐sequencing to investigate the target genes of circPVT1 with circPVT1‐knockdown cells and corresponding control cells. 428 genes were found to be downregulated in circPVT1‐knockdown cells (Figure 7A). Then, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis based on these differentially expressed genes to predict the potential biological function of circPVT1. GO enrichment analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes in circPVT1‐knockdown cells are enriched in several biological processes, including regulation of transcription, cell cycle, and proliferation (Figure S2). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that circPVT1‐related genes are enriched in significant pathways, including pathways in cancer and microRNAs in cancer (Figure 7B). Then, we used the bioinformatics software TargetScan and MiRPathDB to screen miR‐145‐5p–regulated genes. TargetScan and MiRPathDB predicted 773 and 1858 miR‐145‐5p–regulated genes, respectively. Interestingly, 18 circPVT1‐regulated genes were also located in miR‐145‐5p–regulated genes (Figure 7C). These candidate target genes were selected for further investigation. We analyzed the relationship between these candidate genes and the prognosis of ccRCC patients. Only one of these candidate genes, TBX15 was significantly associated with the prognosis of ccRCC patients. ccRCC patients in the high–TBX15‐expression group had a shorter overall survival and disease free survival than ccRCC patients in the low–TBX15‐expression group (log‐rank P < .05) (Figure 7D,E). Then, we explored TBX15 expression in ccRCC tissues and we found that TBX15 mRNA expression was higher in ccRCC tissues (n = 523) than in normal tissues (n = 100) in TCGA database (Figure 7F). Consistently, we found TBX15 was overexpressed in our local ccRCC tissues (n = 20) (Figure 7G). Next, dual‐luciferase reporter assays were performed to verify this interaction between miR‐145‐5p and TBX15. The results showed that transfection of miR‐145‐5p mimic could significantly reduce the luciferase intensity of the 293T cell cotransfected with wild‐type TBX15‐3’UTR compared with mimic‐NC, while no significant changes were observed in the mutant TBX15‐3’UTR group. (Figure 7H). We also found that TBX15 mRNA expression was significantly decreased in circPVT1‐knockdown cells compared with the negative control, and miR‐145‐5p mimic could significantly downregulate TBX15 mRNA expression compared with mimic‐NC (Figure 7I,J). Western blot analysis also confirmed that knockdown of circPVT1 and miR‐145‐5p mimic could suppress the expression of TBX15 (Figure 7K). Additionally, the expression levels of TBX15 protein were higher in ccRCC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues (representative images of Western blot and IHC are shown in Figure 7L). Taken together, our studies revealed that circPVT1 promoted ccRCC progression through regulating the miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis.

FIGURE 7.

circPVT1 regulated the miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A, Volcano plot visualizes the differentially expressed mRNAs in circPVT1‐knockdown and negative control cells. The red and blue dots represent upregulated and downregulated mRNAs with fold change > 2, respectively. B, KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs in circPVT1‐knockdown and negative control cells. C, Venn diagram showing 18 miR‐145‐5p‐regulated genes predicted by RNA‐seq, TargetScan, and MiRPathDB. D, Kaplan‐Meier analysis was performed to assess the relationship between TBX15 expression and overall survival of ccRCC patients. E, Kaplan‐Meier analysis was performed to assess the relationship between TBX15 expression and disease‐free survival of ccRCC patients. F, Relative expression of TBX15 mRNA between ccRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues from TCGA database. G, Relative expression of TBX15 mRNA between 20 pairs of ccRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. H, 293T cell was cotransfected with TBX15‐Wild or TBX15‐Mut with miR‐145‐5p mimic. I, Relative expression of TBX15 mRNA in ccRCC cell lines treated with Si#circPVT1 or Si#NC. J, Relative expression of TBX15 mRNA in ccRCC cell lines treated with mimic‐NC or miR‐145‐5p mimic. K, Western blot analysis of TBX15 in ccRCC cell lines treated with circPVT1 knockdown or miR‐145‐5p mimic. Representative images of TBX15 in ccRCC tissues relative to normal adjacent tissues are shown. L, Representative immunohistochemistry (IHC) images of TBX15 in ccRCC tissues and normal adjacent tissues. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

4. DISCUSSION

Recent studies have demonstrated that ncRNAs are abundant in human transcriptome and play significant roles in carcinogenesis and cancer progression. 20 circRNAs are a new type of ncRNA with salient features of remarkable stability and abundance. Recent studies have demonstrated the significant roles of circRNAs in cancer development and progression. 21 , 22 Identifying and investigating the differentially expressed circRNAs and their roles in cancers is an emerging promising research topic. However, few circRNAs in ccRCC were well characterized and reported.

In this study, we reanalyzed RNA‐sequencing data GSE108735 and identified an oncogenic circRNA, circPVT1, in ccRCC. Previous studies revealed that circPVT1 was involved in the progression of gastric cancer, osteosarcoma, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. 23 , 24 , 25 We found that circPVT1 was significantly overexpressed in both ccRCC tissues and serum of ccRCC patients and associated with the clinical stage. Early diagnosis can effectively guide clinical treatment and significantly increase the radical operation rate and survival rate in ccRCC. 26 Identification of specific biomarkers can be an effective approach for early diagnosis. 27 circRNAs possess ideal features to serve as specific biomarkers, including being stable and enriched in cells, tissues, and even in serum. In this study, we found that the AUCs of tissue and serum circPVT1 expression were 0.93 and 0.86, respectively, suggesting the potential role of circPVT1 in ccRCC diagnosis and treatment. Loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function experiments showed that circPVT1 knockdown suppressed proliferation and invasion in ccRCC cells, which could be attenuated by miR‐145‐5p inhibitor. circPVT1 overexpression significantly promoted growth in ccRCC, which was also verified by xenograft experiments in vivo. These functional experiments revealed the oncogenic role of circPVT1 in ccRCC and provided a potential therapeutic target for ccRCC patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report to investigate the expression, clinical significance, biological function, and molecular mechanism of circPVT1 in ccRCC.

The ceRNA hypothesis suggests that circRNAs could serve as miRNA sponges and regulate the transcription of downstream target genes. circRNA circHIPK3 regulated autophagy through miR‐124‐3p‐STAT3‐PRKAA/AMPKα signaling in STK11 mutant lung cancer. 28 circRNA hsa_circ_0091570 suppressed hepatocellular cancer via sponging miR‐1307. 29 circPCNXL2 promoted the proliferation and invasion of renal cells through sponging miR‐153 and regulating ZEB2. 30 We screened candidate miRNAs using a bioinformatics tool CircInteractome and focused on miR‐145‐5p. Biotin‐labeled miRNA pulldown assay and dual‐luciferase reporter assay were performed to demonstrate the direct binding of circPVT1 and miR‐145‐5p. Rescue experiments revealed circPVT1 knockdown suppressed ccRCC proliferation and invasion dependently on miR‐145‐5p. Then, we performed RNA‐sequencing and bioinformatics analysis to screen the target gene of the circPVT1/miR‐145‐5p axis. We found that circPVT1 knockdown significantly reduced the TBX15 expression in ccRCC cells. Consistently, miR‐145‐5p mimic increased and miR‐145‐5p inhibitor reduced the TBX15 expression in ccRCC cells. Moreover, TBX15 expression is positively associated with the overall survival and disease‐free survival of ccRCC patients. These data revealed a new regulatory model of circRNA in ccRCC, namely that circPVT1 serves as a ceRNA by competitively binding to miR‐145‐5p to regulate the expression of its target gene TBX15 and promotes the progression of ccRCC.

In summary, we identified an oncogenic circRNA circPVT1, which was overexpressed in ccRCC tissues and promoted the growth and metastasis of ccRCC in vivo and in vitro. circPVT1 directly bound to miR‐145‐5p and subsequently inhibited its suppressing capability on TBX15. Our study highlighted the regulatory role of the circPVT1/miR‐145‐5p/TBX15 axis in ccRCC and provided a novel potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for ccRCC patients.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1‐S2

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81672534), a grant from Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2019A1515012199), and a grant ([2013]163) from the Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Molecular Mechanism and Translational Medicine of Guangzhou Bureau of Science and Information Technology.

Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhong Q, et al. CircPVT1 promotes progression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma by sponging miR‐145‐5p and regulating TBX15 expression. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:1443–1456. 10.1111/cas.14814

Zaosong Zheng and Zhiliang Chen are contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Capitanio U, Montorsi F. Renal cancer. Lancet. 2016;387:894‐906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2009;373:1119‐1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Crispen PL, et al. Histological subtype is an independent predictor of outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2010;183:1309‐1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, Thum T. Non‐coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1297‐1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS, Slack FJ. Non‐coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:5‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang H, Huang X, Wang J, et al. circKIF4A acts as a prognostic factor and mediator to regulate the progression of triple‐negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei S, Zheng Y, Jiang Y, et al. The circRNA circPTPRA suppresses epithelial‐mesenchymal transitioning and metastasis of NSCLC cells by sponging miR‐96‐5p. Ebiomedicine. 2019;44:182‐193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen S, Huang V, Xu X, et al. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell. 2019;176:831‐843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vo JN, Cieslik M, Zhang Y, et al. The landscape of circular RNA in cancer. Cell. 2019;176:869‐881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kong YW, Ferland‐McCollough D, Jackson TJ, Bushell M. microRNAs in cancer management. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:E249‐E258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qiu M, Xia W, Chen R, et al. The circular RNA circPRKCI promotes tumor growth in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2839‐2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Han D, Li J, Wang H, et al. Circular RNA circMTO1 acts as the sponge of MicroRNA‐9 to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2017;66:1151‐1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang J, Liu H, Hou L, et al. Circular RNA_LARP4 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer by sponging miR‐424‐5p and regulating LATS1 expression. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dudekulay DB, Panda AC, Grammatikakis I, De S, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. CircInteractome: a web tool for exploring circular RNAs and their interacting proteins and microRNAs. RNA Biol. 2016;13:34‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Backes C, Kehl T, Stöckel D, et al. miRPathDB: a new dictionary on microRNAs and target pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D90‐D96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tang ZF, Li CW, Kang BX, Gao G, Li C, Zhang ZM. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98‐W102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y, Mo Y, Gong Z, et al. Circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsiao K‐Y, Lin Y‐C, Gupta SK, et al. Noncoding effects of circular RNA CCDC66 promote colon cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2339‐2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guarnerio J, Bezzi M, Jeong JC, et al. Oncogenic role of fusion‐circRNAs derived from cancer‐associated chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2016;166:1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen J, Li Y, Zheng Q, et al. Circular RNA profile identifies circPVT1 as a proliferative factor and prognostic marker in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;388:208‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verduci L, Ferraiuolo M, Sacconi A, et al. The oncogenic role of circPVT1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated through the mutant p53/YAP/TEAD transcription‐competent complex. Genome Biol. 2017;18:237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu KP, Ma XL, Zhang CL. Overexpressed circPVT1, a potential new circular RNA biomarker, contributes to doxorubicin and cisplatin resistance of osteosarcoma cells by regulating ABCB1. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:321‐330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morrissey JJ, Mellnick VM, Luo J, et al. Evaluation of urine Aquaporin‐1 and Perilipin‐2 concentrations as biomarkers to screen for renal cell carcinoma a prospective cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:204‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shuch B, Zhang J. Genetic predisposition to renal cell carcinoma: implications for counseling, testing, screening, and management. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3560‐3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen XY, Mao R, Su WM, et al. Circular RNA circHIPK3 modulates autophagy via MIR124‐3p‐STAT3‐PRKAA/AMPK alpha signaling in STK11 mutant lung cancer. Autophagy. 2020;16:659‐671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang YG, Wang T, Ding M, Xiang SH, Shi M, Zhai B. hsa_circ_0091570 acts as a ceRNA to suppress hepatocellular cancer progression by sponging hsa‐miR‐1307. Cancer Lett. 2019;460:128‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou B, Zheng P, Li Z, et al. CircPCNXL2 sponges miR‐153 to promote the proliferation and invasion of renal cancer cells through upregulating ZEB2. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:2644‐2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S2

Table S1‐S2

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material