Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to understand the potential barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 vaccination among youth.

Methods

Open-ended questions regarding COVID-19 vaccination were posed to a national cohort of 14- to 24-year-olds (October 30, 2020). Responses were coded through qualitative thematic analysis. Multivariable logistic regression tested the association of demographic characteristics with vaccination unwillingness.

Results

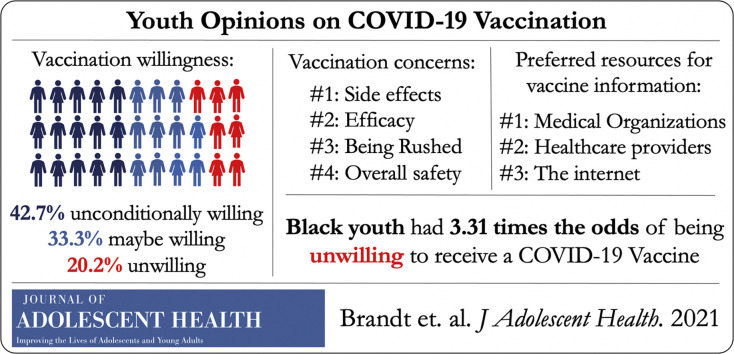

Among 911 respondents (response rate = 79.4%), 75.9% reported willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, 42.7% had unconditional willingness, and 33.3% were conditionally willing, of which the majority (80.7%) were willing if experts deemed vaccination safe and recommended. Preferred vaccine information sources were medical organizations (42.3%; CDC, WHO) and health care professionals (31.7%). Frequent concerns with vaccination included side effects (36.2%) and efficacy (20.1%). Race predicted vaccination unwillingness (Black: odds ratio = 3.31; and Asian: odds ratio = .46, compared with white, p < .001).

Conclusion

Most youth in our national sample were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine when they believe it is safe and recommended. Public health experts and organizations must generate youth-centered materials that directly address their vaccination concerns.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine, Mixed methods, Youth

Graphical abstract

Implications and Contribution.

Most youth in this national sample were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine if it is perceived as safe and recommended by trusted experts. Youth-centered materials from governmental and youth-serving organizations that directly address their concerns should be prioritized to increase vaccination among youth and promote greater public health.

Widespread vaccination is crucial to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. The proportion of youth accounting for COVID-19 cases has increased over time and is a critical source of spread to more vulnerable populations; thus, it will be essential to vaccinate youth to achieve herd immunity [2,3]. We collected the thoughts and opinions from a diverse national sample of youth regarding COVID-19 vaccine acceptability, preferred information sources, and concerns to inform potential barriers to COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods

MyVoice is an ongoing national text message poll seeking youth (aged 14–24 years) opinions on health and policy issues [4]. Participants were recruited on a rolling basis through social media to meet national demographic benchmarks (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and region) based on weighted samples of the American Community Survey. Five open-ended questions, developed with a team of youth, physicians, and qualitative research experts, were fielded on October 30, 2020, via text message regarding COVID-19 vaccination [5]. We report results from three questions: “When a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, will you get it? Why or why not?”, “Where would you go to get information about a COVID-19 vaccine? Why?”, and “What concerns, if any, do you have about getting a vaccine for COVID-19?” The authors developed a codebook through qualitative thematic analysis of responses. Responses were independently coded by two investigators using discussion to reach consensus. Summary statistics of demographic data and code frequencies were calculated. Based on qualitative analysis, we grouped responses into three groups: willing, not committed, and unwilling to receive a vaccine. Multivariable logistic regression assessed the outcome of unwillingness for vaccination, controlling for age (<18 years or >18 years), gender, race, ethnicity, and region. p values were two tailed. Statistical significance was set at <.05. Analyses were completed using Stata 16 (StataCorp, LLC). This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, including a waiver of parental consent for minor participants. Online consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Of 1,147 participants, 911 responded to at least one question (response rate = 79.4%). The median age was 18 years (interquartile range: 17–21), 48% identified as female, 64% as white, and 13% as Hispanic (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study sample (n = 911)

| Characteristic | Respondents, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (IQR), years | 18 (17, 21) |

| 14–17 | 323 (35.5%) |

| 18–24 | 588 (64.5%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 400 (43.9%) |

| Female | 439 (48.2%) |

| Other | 72 (7.9%) |

| Race | |

| White | 583 (64.0%) |

| Black | 80 (8.8%) |

| Asian | 131 (14.4%) |

| Other/mixed | 116 (12.7%) |

| Hispanic | 116 (12.7%) |

| Region | |

| Midwest | 308 (33.8%) |

| Northeast | 145 (15.9%) |

| South | 258 (28.3%) |

| West | 198 (21.7%) |

Overall, 75.9% reported a degree of willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 (Table 2 ). Unconditional willingness was reported by 42.7% (“Yes, absolutely!”) and conditional willingness (“it depends”) by 33.3%, of which the majority (80.7% of those “Not committed”) were willing if experts deemed vaccination safe and recommended (“if it is proven safe by reliable scientists”). Protecting oneself and others (family, friends, community members) was the most frequent reason for willingness to vaccinate. Among the 20.2% of youth who reported unwillingness to vaccinate, safety was the foremost concern (“have not been enough trials to prove its safety”).

Table 2.

Participant willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccination and supporting themes

| Themea | n (%) | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (willing to get vaccine) | 385 (42.7%) | |

| Protect self | 148 (38.4%) | “Yes, to keep myself safe” “I will most likely get it because I don't want covid” |

| To protect others | 95 (24.7%) | “Yes because it's for the safety of others” “Yes, absolutely! Because I want to protect myself, my family & friends” |

| Vaccines are important | 55 (14.3%) | “Yes vaccines are safe and reliable…” “YES absolutely!!!! i believe herd immunity is crucial to the wellbeing of a lot of people…” |

| To return to normalcy | 45 (11.7%) | “I will get it so that I can hopefully go back to my normal life” “yes i want to go back to school and keep myself and others safe” |

| Vaccine is believed safe | 28 (7.3%) | “Yes bc i will believe they've done enough testing for it to be safe” “Probably, I believe the FDA will approve it when it's trusted” |

| Stop worry | 24 (6.2%) | “Yes so I can stop worrying about catching it” “Yes, I want to live without being afraid of COVID” |

| Must get it for their job | 7 (1.8%) | “Yes because I'm taking care of patients” “Yes I work with kids” |

| Not committed/conditional willingness (e.g., “yes, if” or “depends”) | 300 (33.3%) | |

| If it is safe and recommended | 242 (80.7%) | “Yes, I will get it if it is recommended by public health officials. I trust the science and believe that people in public health will only recommend a vaccine that is safe” “I probably will if it has been shown to be effective and no or minimal side effects” |

| Political concerns | 39 (13.0%) | “Maybe, only if it is proven safe by reliable scientists and not a political move” “I will get it only if multiple reliable sources say that it is safe (the White House does not qualify)” |

| If required | 15 (5.0%) | “But if it's required then yeah” “I'm assuming I'll have to since I work in healthcare" |

| After vulnerable people get it | 9 (3.0%) | “…I'll wait for people who need it more to get it first” “I don't want to get it when it first comes out because there are more vulnerable people who need it more” |

| If they can afford it | 9 (3.0%) | “I would get it if it's covered by my insurance, otherwise I probably cant afford it” “Yes I will if it's free!” |

| No (unwilling to get vaccine) | 182 (20.2%) | |

| Not safe or trusted | 85 (46.7%) | “No because I don't believe it has gone through the necessary testing to make sure it's safe” “Hell no !!! I am not a lab rat!” |

| Political concerns | 11 (6.0%) | “No I don't trust the government” “No. i don't want to get a vaccine that hasn't been around for very long, plus there is no proof that the government isn't brainwashing us” |

| I'm healthy | 11 (6.0%) | “No I don't care to get it. I think my immune system is good” “No. Because I have not shown any signs or symptoms of Covid” |

| COVID-19 not real/not dangerous | 5 (2.7%) | “No, covid isn't deadly to my demographic and really is overblown” “hell nah cause covid is a whole scam” |

| Allergy/other health concern | 5 (2.7%) | “Every vaccine I have taken has given me a violent reaction” “No, I am highly allergic to some of the ingredients in vaccines” |

| Afraid of needles | 4 (2.2%) | “No I'm scared of needles” “Nope. I bloody hate needles.” |

| Had COVID-19 already | 4 (2.2%) | “No. I already went through it and don't feel a need for a vaccine.” “I will not be getting the vaccine. My family and I have already had COVID.” |

| Already taking precautions | 3 (1.6%) | “No. I haven't been out in public.” “No because it maybe pretty expensive and I can just stay inside” |

| Not sure | 35 (3.9%) | “I personally do not know.” |

Themes are mutually exclusive, while sub-themes are not mutually exclusive.

Race was the sole predictor of unwillingness to vaccinate. Black youth were more likely to be unwilling (odds ratio = 3.31), whereas Asian youth were less likely (odds ratio = .46) to decline vaccination compared with white youth (p < .001).

Scientific and medical organizations (42.3%; “CDC” or “WHO”) were the most preferred sources of COVID-19 vaccine information. Other trusted sources for information included health care providers and facilities (31.7%; “pharmacy,” “doctors office,” and “hospital or clinic”), “the internet” (17.8%), “health officials” (8.4%), or news media (7.8%; “Reuters,” “BBC”). Only 2.5% mentioned social media (“social media like twitter”). Sources were chosen for their trustworthiness (27.5%; “seem reliable”), authority or expertise (14.4%; “they are professionals”), convenience (7.8%; “the easiest accessible source”), and being unbiased (3.0%; “not politically biased”).

The major concerns about a COVID-19 vaccine included side effects (36.2%; “bad side effects”), efficacy (20.1%; “COVID mutates” or “if it'll even work”), the vaccine being rushed (18.8%), and safety (16.2%; “It's unsafe.”). Less common concerns included government or industry influence (4%; “for political gain”), vaccination causing COVID-19 (3%), and conspiracies (2%; “nanotrackers”).

Discussion

Most youth in our national sample were willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19, although many would wait until they felt the vaccine was “safe and recommended.” Youth looked specifically to scientific, medical, and health care sources to inform their decisions. Primary concerns included side effects, efficacy, and safety. Black race was associated with an unwillingness to vaccinate. Our findings are unique in that they were observed among youth, although they reflect observations from studies of adults, including that most are willing to be vaccinated once they perceive vaccination to be safe and effective [6,7].

COVID-19 vaccines have been tested on cohorts aged ≥12 years and approved for those aged ≥16 years [[8], [9], [10]]. Youth vaccination is particularly important, given their role in spreading disease to more vulnerable individuals and need to reach herd immunity. However, younger adults have historically had lower vaccination rates for seasonal infections (e.g., influenza) [11]. Similar challenges may exist for COVID-19 vaccination in light of relatively lower rates of serious infections among younger patients. Many young adults also feel ill-prepared to navigate the health care system and may avoid care as a result [12]. Coordinated efforts beyond education will be necessary to ensure youth feel knowledgable and empowered to make appropriate decisions regarding vaccination, especially because this may be the first important medical decision they will be involved in or make for themselves.

Youth in our study reported trusting and searching for information on scientific websites (“CDC” and “WHO”). However, most scientific resources are designed for parents, school administrators, and health care providers. These sources of information should prepare accurate, youth-centered information that speaks to youth issues from all backgrounds, including the need to work, socialize, and go to school. Our study suggests that clear and consistent communication and coordinated efforts between public health and medical providers are necessary to ensure youth are fully engaged in vaccination efforts, especially because prior work has already shown the power of providers to increase intention for vaccination [13]. Materials should use engaging, youth-friendly materials that directly address safety, side effects, and efficacy to allay the fears and uncertainty among the youth that would become willing to vaccinate if such issues were addressed.

We found differences in vaccination willingness by race, which is concerning because Black Americans already face a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 [14]. Our results confirm observations that Black American may be more likely to reject vaccination, primarily from lack of trust [6]. Without directly addressing potential differences in vaccination willingness, racial disparities from COVID-19 are likely to worsen. Tailored after other successful programs that have addressed disparities in health care, broad engagement of historically marginalized community members at every level of planning and implementation will inform the design of effective programs and has the potential to improve community-level knowledge and engagement in vaccine dissemination [15,16].

Responses should be contextualized by survey timing because it was administered before the release of vaccine efficacy data and near the presidential election.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

This research was funded by the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research and the University of Michigan Departments of Internal and Family Medicine. These funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.Mahase E. Covid-19: Expedite vaccination or deaths will surge, researchers warn. BMJ. 2020;371:m4958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehmer T.K., DeVies J., Caruso E. Changing age distribution of the COVID19 pandemic — United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020. 2020;69:1404–1409. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimet G.D., Silverman R.D., Fortenberry J.D. Coronavirus disease 2019 and vaccination of children and adolescents: Prospects and challenges [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 5] J Pediatr. 2020;231:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeJonckheere M., Nichols L.P., Moniz M.H. MyVoice national text message survey of youth aged 14 to 24 Years: Study protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6:e247. doi: 10.2196/resprot.8502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Question Bank: COVID-19 vaccines. https://hearmyvoicenow.org/questionbank/?SingleProduct=99 Available at: Published 2020. Updated October 23, 2020. Accessed November 26, 2020.

- 6.Lin C., Tu P., Beitsch L.M. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;9:16. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidry J.P.D., Laestadius L.I., Vraga E.K. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 8.ClinicalTrials.gov A study to evaluate efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 vaccine in adults aged 18 years and older to prevent COVID-19. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04470427 Available at:

- 9.ClinicalTrials.gov Study to describe the safety, tolerability, immunogenicity, and efficacy of rna vaccine candidates against COVID-19 in healthy individuals. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04368728 Available at:

- 10.U.S. Food & Drug Administration Emergency use authorization. https://www.fda.gov/media/144412/download Available at:

- 11.Lu P.J., Hung M.C., O'Halloran A.C. Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage trends among adult populations, U.S., 2010-2016. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuiteman S., Chua K.P., Plegue M.A. Self-management of health care among youth: Implications for policies on transitions of care. J Adolesc Health. 2020 May;66:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Center for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 hospitalization and death by race/ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/coviddata/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html CDC. Available at: Published 2020. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed November 26, 2020.

- 14.Head K.J., Kasting M.L., Sturm L.A. A national survey assessing SARS-CoV-2 vaccination intentions: Implications for future public health communication efforts. Sci Commun. 2020;42:698–723. doi: 10.1177/1075547020960463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Commonwealth Fund In focus: Reducing racial disparities in healthcare by confronting racism. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletterarticle/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting Available at:

- 16.Health Partners HealthPartners recognized for colorectal cancer screening efforts. https://www.healthpartners.com/hp/about/press-releases/recognized-for-colorectalcancer-screening-efforts.html Available at: