Abstract

Expert recommendations to discuss prognosis and offer palliative options for critically ill patients at high risk of death are variably heeded by intensive care unit (ICU) clinicians. How to best promote such communication to avoid potentially unwanted aggressive care is unknown. The PONDER-ICU (Prognosticating Outcomes and Nudging Decisions with Electronic Records in the ICU) study is a 33-month pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial testing the effectiveness of two electronic health record (EHR) interventions designed to increase ICU clinicians’ engagement of critically ill patients at high risk of death and their caregivers in discussions about all treatment options, including care focused on comfort. We hypothesize that the quality of care and patient-centered outcomes can be improved by requiring ICU clinicians to document a functional prognostic estimate (intervention A) and/or to provide justification if they have not offered patients the option of comfort-focused care (intervention B). The trial enrolls all adult patients admitted to 17 ICUs in 10 hospitals in North Carolina with a preexisting life-limiting illness and acute respiratory failure requiring continuous mechanical ventilation for at least 48 hours. Eligibility is determined using a validated algorithm in the EHR. The sequence in which hospitals transition from usual care (control), to intervention A or B and then to combined interventions A + B, is randomly assigned. The primary outcome is hospital length of stay. Secondary outcomes include other clinical outcomes, palliative care process measures, and nurse-assessed quality of dying and death.

Clinical trial registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 03139838).

Keywords: critical care, artificial respiration, palliative care, clinical trial

Many patients with life-limiting illnesses receive aggressive care in their final months of life (1–3). Aggressive care near life’s end may be misaligned with patients’ goals (4, 5) and is associated with reduced quality of life (6, 7). Moreover, family members of patients who die in intensive care units (ICUs) commonly experience pathological bereavement (6–11). For these reasons, guidelines recommend that clinicians discuss prognosis and offer the option of care focused on comfort for critically ill patients at high risk of death or severely impaired functional recovery (12–14). However, ways to promote adherence to these guidelines have yet to be identified.

It is tempting to believe that specialist palliative care consultation or communication interventions will improve the quality of palliative care in the ICU. And indeed, several efficacy studies have shown that such interventions improve outcomes for critically ill patients under controlled circumstances (15–19). However, to date, larger effectiveness trials of similarly resource-intensive palliative interventions have had mixed results (20–22). Relying on palliative care specialists to see all critically ill patients at high risk of death (23) is neither feasible nor sustainable because of their short supply (24–28), and palliative care educational initiatives for ICU clinicians require considerable upfront investment with uncertain benefit (29, 30). Furthermore, the effectiveness of interventions targeting surrogates may be limited by their modest knowledge of patients’ end-of-life care preferences (31–33) and, often, excessive optimism (34).

By contrast, interventions designed to change ICU clinician behavior hold great promise (35) but have rarely been tested (36). Specifically, increasing the frequency and timeliness of ICU clinicians’ engagement of critically ill patients and their surrogates about their goals and all potential treatment options may better align the care delivered with patient preferences and reduce family distress and bereavement (37–41). Thus, with support from the Donaghue Foundation, we are conducting the PONDER-ICU (Prognosticating Outcomes and Nudging Decisions with Electronic Records in the ICU) study, a multicenter trial representing a collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania and Atrium Health, one of the largest health systems with integrated electronic health record (EHR) technology in the United States. This study’s protocol is designed to test our hypotheses that patient-centered outcomes can be improved by simple, scalable EHR-based interventions that nudge ICU clinicians to document patients’ functional prognoses, offer care focused on comfort, or both.

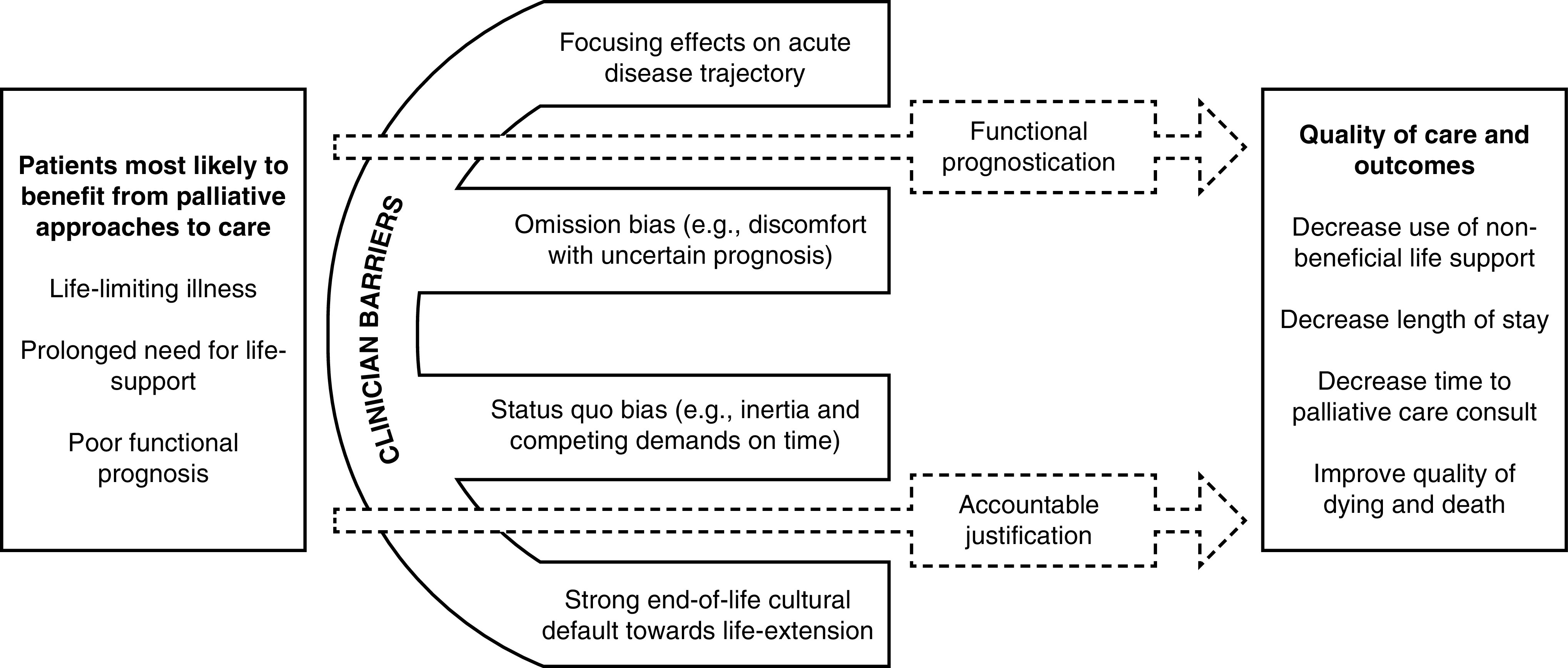

Conceptual Model for Nudging ICU Clinicians to Improve Palliative Care

Many factors unrelated to patients, such as which ICU clinician is responsible for the patient’s care, which ICU the patient is admitted to, and how busy the ICU is that day, strongly influence whether or not hospitalized patients will receive life support or ongoing critical care (42–44). Similarly, physicians largely determine whether or not comfort care will be offered for critically ill patients (45, 48), with the physician’s belief that life support should be withheld or withdrawn being a highly determinative factor (49, 50). Our conceptual model in Figure 1 stems from evidence of clinicians’ failures to reliably identify seriously ill patients appropriate for palliative approaches to care (42, 49–51) and several well-described barriers clinicians face in initiating these discussions (51–55). Past efforts to improve clinicians’ prognostic awareness and goals-of-care conversations for seriously ill hospitalized patients who have relied on information provision alone, communication-skills training, or specially trained interventionalists have been largely ineffective (21, 56, 57). In contrast, behavioral economic insights offer novel, scalable, and potentially powerful approaches to promote goal-concordant care by targeting specific clinician barriers and “nudging” recommended communication behaviors gently without restricting their choice (58–61). Furthermore, EHR-based nudges have been effective at increasing clinicians’ adherence to guidelines in several practice settings (62–65).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of barriers to intensive-care-unit clinicians’ offering palliative approaches to care.

Methods

Study Objectives

The objectives of the PONDER-ICU trial are to 1) provide experimental evidence of how two behavioral, EHR-based interventions designed to increase ICU clinicians’ engagement of critically ill patients and surrogates in discussions about the option of comfort-focused care impact patient-centered outcomes; 2) assess the extent to which the effectiveness of each intervention or the combination of both varies among clinicians; and 3) identify patient subgroups for whom the interventions are particularly effective.

Study Design and Setting

PONDER-ICU is a pragmatic, multicenter, stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial in which all hospitals begin in a usual-care control phase and adopt one or the other intervention in a randomly assigned sequence. The stepped-wedge study design was chosen because of certain practical and scientific advantages over traditional parallel cluster randomized designs (66–69). Importantly, given the baseline variability in processes of care across hospitals and ICUs (42, 70–72), the stepped-wedge design enables comparisons of outcomes before and after implementation within hospitals as well as at a given point in time among hospitals, which will have been, at that time, randomly assigned to different interventions (73).

We designed this study in close adherence to the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 criteria for pragmatic clinical trials and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials extension for stepped-wedge cluster randomized trials (74–76). The trial is being conducted in 17 ICUs across 10 hospitals within Atrium Health (formerly Carolinas HealthCare System), one of the nation’s largest healthcare organizations, with more than 40 hospitals across North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Participating hospitals use an EHR produced by Cerner Corporation, which feeds into Atrium’s centralized data warehouse and connects across all care settings within the health system. Three ICUs are closed units (intensivist as primary attending physician), and 14 are open units (hospitalist or surgeon as primary attending physician) with selective intensivist consultation (72), including for all patients receiving mechanical ventilation (Table 1). Some ICUs also have house staff and/or advanced-practice providers (nurse practitioner or physician assistant) as additional bedside clinicians, and all ICUs in this trial have critical care telemedicine available (24-hour nurse and nocturnal-intensivist support).

Table 1.

Geography and characteristics of the participating Atrium Health hospitals and ICUs (n = 17) in North Carolina

| Hospital | Setting | ICU Type | No. of Beds | Staffing Model*† | Additional Bedside Clinicians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabarrus | Urban, regional referral | Cardiothoracic | 4 | Closed | APP |

| Cardiac | 10 | Closed | APP | ||

| Medical–surgical | 35 | Closed | APP | ||

| CMC | Urban, academic center | Cardiothoracic | 14 | Open | APP; house staff‡ |

| Cardiac | 20 | Open | APP; house staff | ||

| Medical | 29 | Open | APP; house staff | ||

| Neurosurgical | 29 | Open | APP; house staff | ||

| Trauma | 29 | Open | APP; house staff | ||

| CMC-Mercy | Urban, community | Medical–surgical | 20 | Open | None |

| Blue Ridge–Morganton | Rural | Medical–surgical | 10 | Open | APP |

| Cleveland | Rural | Medical–surgical | 18 | Open | None |

| Lincoln | Rural | Medical–surgical | 10 | Open§ | None |

| Pineville | Urban, community | Cardiac | 14 | Open | None |

| Medical | 16 | Open | None | ||

| Stanly | Rural | Medical–surgical | 10 | Open | None |

| Union | Suburban | Medical–surgical | 14 | Open | None |

| University City | Urban, community | Medical–surgical | 8 | Open | None |

Definition of abbreviations: APP = advanced-practice provider; CMC = Carolinas Medical Center; ICU = intensive care unit.

Closed ICUs have intensivists as the primary attending physicians; open ICUs have hospitalists or surgeons as the primary attending physicians, with required intensivist consultation for patients receiving mechanical ventilation or vasoactive infusions and for those with a life-threatening emergency.

All participating ICUs have critical care telemedicine available, including 24-hour nurse and nocturnal-intensivist support.

House staff may include resident physicians and/or fellows.

No bedside intensivist available.

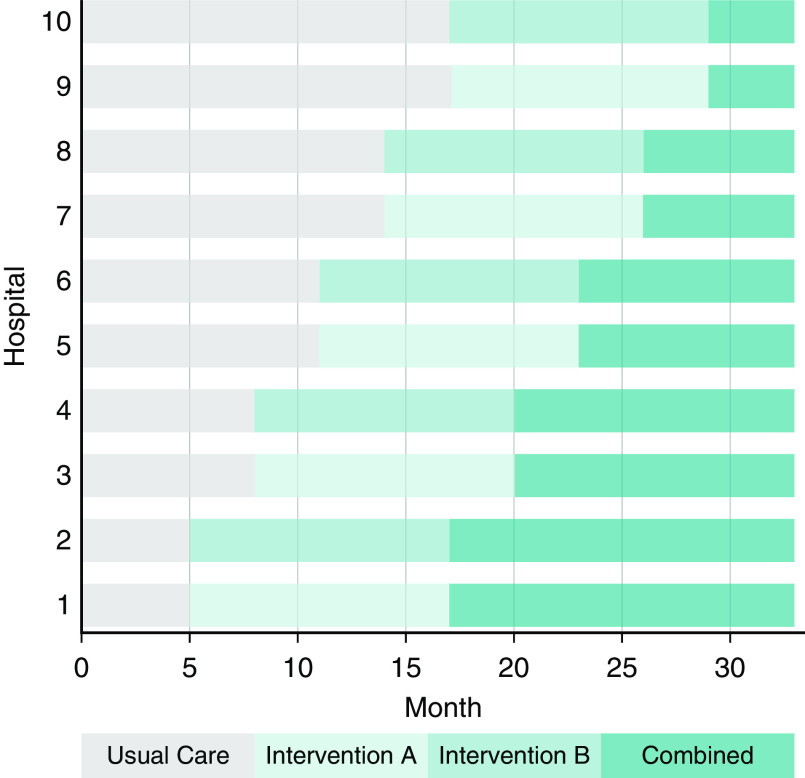

The 10 study hospitals were randomly grouped into five clusters of 2 hospitals each. Every 3 months, a new hospital cluster adopts the interventions in a sequence determined by computerized random-number generation, and within each cluster, one hospital is randomly assigned to begin with intervention A and the other is assigned to begin with intervention B (Figure 2). All hospitals contribute a minimum of 5 months of usual-care (control) data before adopting either intervention; by the end of the 33-month study period, all hospitals will have been using both interventions combined for at least 4 months. This design enables comparisons of each intervention alone and both interventions combined with usual care (77).

Figure 2.

Schematic of the PONDER-ICU (Prognosticating Outcomes and Nudging Decisions with Electronic Records in the Intensive Care Unit) pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial. The sequence and timing with which each hospital transitions between phases is randomly assigned. Wedge intervals are 3 months after all hospitals spend a minimum of 5 months in the usual-care phase; the total trial duration is 33 months.

Identification of Eligible Critically Ill Patients

Discussions regarding goals of care, and the option of focusing primarily on comfort in particular, are wrought with complexities and may be distressing to patients and surrogates (8, 10, 11, 78, 79). Such discussions also require substantial time and energy from clinicians and thus must be reserved for the patients most likely to benefit from them. We sought to identify adult patients likely to benefit from a timely discussion of prognosis and palliative care options (26) and to include a diverse population to promote generalizability. Existing evidence suggests that patients with preexisting life-limiting illnesses are at high risk of mortality in critical illness with organ failure (80–85), and among survivors, few return to their baseline functional status (86). Thus, eligible patients include adults (≥18 yr) with a preexisting life-limiting illness (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, dementia, end-stage renal disease, leukemia or lymphoma, pulmonary fibrosis/interstitial lung disease, or solid organ malignancy) as determined by the presence of one or more applicable International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification code(s) (see Table E1 in the online supplement) within the prior 365 days and acute respiratory failure requiring continuous mechanical ventilation for ≥48 hours (Figure E1).

Eligible patients are identified using an EHR algorithm that includes a real-time calculation of mechanical ventilation duration using the ventilatory data entered by bedside clinicians. To validate the algorithm, we conducted a blinded independent review of 100 medical charts randomly selected from across the 17 participating ICUs. The algorithm identified 51 of these patients as eligible and 49 as ineligible. Using the investigators’ blinded chart review as the gold standard, the EHR eligibility algorithm had a false-positive rate of 0% (i.e., all 51 patients deemed eligible truly met the criteria) and a false-negative rate of 2% (i.e., 1 of the 49 patients deemed ineligible was actually eligible).

Interventions

The interventions each consist of two simple queries that ICU clinicians complete directly in an eligible patient’s EHR, where they are subsequently saved and viewable as a document. For this trial, the ICU clinician is defined as the attending physician (intensivist, hospitalist, or surgeon) and the advanced-practice provider, when applicable, who is primarily responsible for the patient’s medical decision-making at the time of enrollment. In pilot testing among ICU clinicians at two health systems uninvolved in the trial, the time to complete the two queries for each intervention was approximately 2 minutes or less.

Focusing effect (intervention A)

In many contexts, framing choices in ways that focus people on certain elements of the decisions they face can substantially change behavior (87, 88). In a nationwide, scenario-based randomized trial, simply requiring ICU physicians to document a patient’s short-term functional prognosis significantly increased their willingness to discuss the possibility of withdrawal of life support (89). In a follow-up simulation study, requiring ICU physicians to estimate patients’ functional outcomes again changed certain behaviors (90). In this simulation study, although physicians’ likelihood of specifically offering comfort-oriented care was unchanged, they were more likely to disclose a poor prognosis in an initial family meeting. Our trial leverages this focusing effect by prompting clinicians to prognosticate patients’ functional outcomes 6 months later, selecting from options ranging from death to the ability to live at home independently. Although clinicians are required to document this prognostication in the EHR, they are not required as part of the trial to share this information with patients or surrogates.

Accountable justification (intervention B)

Physicians are trained to make decisions backed by reason. Accordingly, prior work has shown that requiring physicians to provide justification for their decisions reduces overuse of resources (91) and inappropriate prescribing practices (64). By requiring physicians to document in the EHR their reasons for not having offered a critically ill patient or their surrogate the option to pursue comfort-oriented care, physicians may reflect more deeply on all of the reasonable care options for the patient and be more likely to follow guidelines to have such discussions. Intervention B prompts clinicians to document whether they have offered the patient or surrogate the option for care focused primarily on comfort and, if not, to explain why not in a free-text box. If clinicians decline to provide a justification, the phrase “No justification given” is automatically populated in the saved electronic document. Visibility of clinicians’ responses in the EHR is essential because lack of public accountability may diminish such interventions’ effects (92–94).

Study Procedures and Data Collection

Enrollment

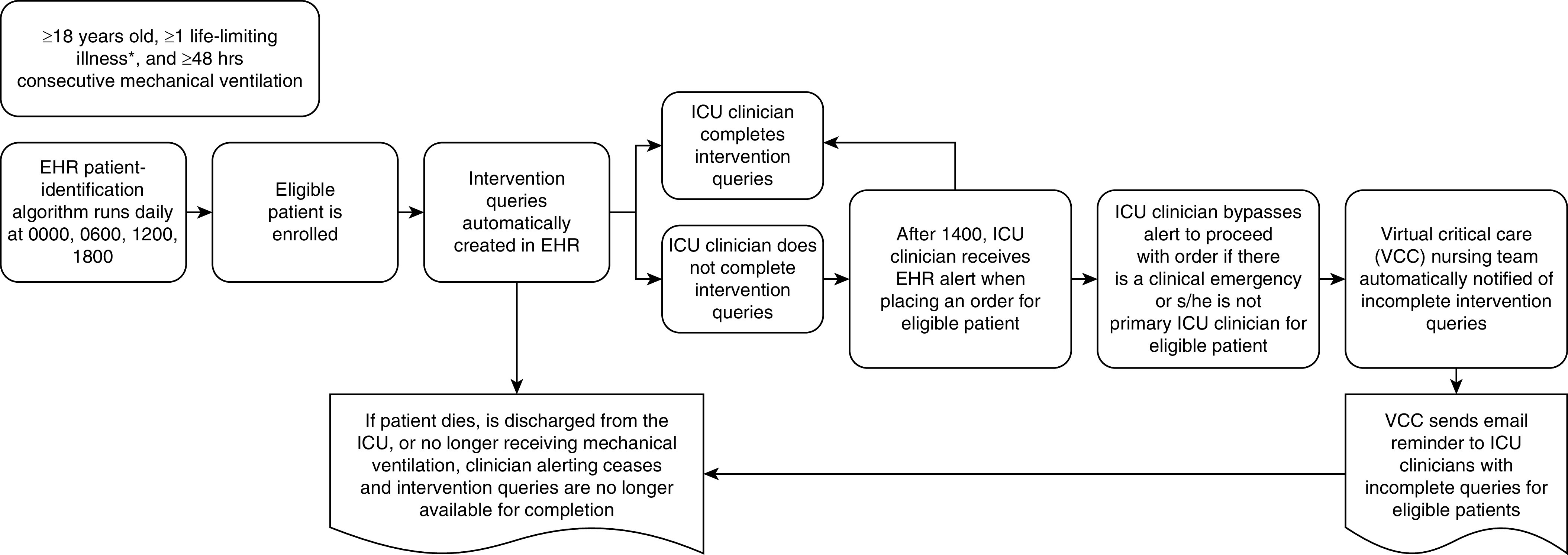

In all phases of the study, the EHR patient-identification algorithm runs four times per day (00:00, 06:00, 12:00, and 18:00) (Figure 3). This frequency was selected in collaboration with the Atrium Health Information and Analytic Services team to balance the scientific goal of maximizing enrollment opportunities and the operations goal of minimizing computational resource burdens on Atrium’s shared information systems. During the intervention phases of the trial, the appropriate queries are automatically generated and are immediately available for completion in the clinicians’ routine EHR document workflow at the time a patient becomes eligible. Clinicians can complete the queries any time up until an eligible patient either dies in the ICU, is discharged from the ICU, or is no longer receiving mechanical ventilation.

Figure 3.

Patient-identification and intervention-delivery schema. *Eligible life-limiting illnesses: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, congestive heart failure, dementia, end-stage renal disease, leukemia or lymphoma, pulmonary fibrosis/interstitial lung disease, or solid organ malignancy. EHR = electronic health record; ICU = intensive care unit; VCC = virtual critical care.

To promote adherence to the interventions, ICU clinicians begin receiving an EHR reminder alert at 14:00 after eligibility determination whenever they attempt to place an order for a patient with incomplete queries until they are completed. This time was chosen to minimize disruptions for newly eligible patients during morning multidisciplinary rounds when ICU clinicians tend to be focused on making acute care plans. Clinicians may bypass the alert and proceed with their intended order if they indicate that there is a clinical emergency (alerting resumes with the subsequent order) or that they are not the primary ICU clinician for the patient. In addition, the telemedicine nursing team is automatically notified of incomplete intervention queries each day. This minimally intrusive monitoring enables the nurses to send e-mail reminders to the appropriate ICU clinician(s).

Trial Regulation and Engagement

The chief medical officers and ICU medical directors at each hospital were notified about the trial 3 months before and again 1 week before initiation of the usual-care phase. ICU clinicians were notified about the trial 1 month before initiation of the usual-care phase and again 2 weeks before their hospital switched to an intervention phase using Atrium’s established communication channels, including e-mail, flyers, and leadership meetings. This trial is being conducted under a waiver of the requirement for informed consent for both patients and clinicians on the basis of the criteria set forth by the “Common Rule.” (95) This waiver, and the entire trial protocol, were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and Atrium Health. Additional methods regarding the human research protections and data management plan for this study are described in the online supplement.

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome

We have chosen hospital length of stay (LOS) as our primary outcome because it can be uniformly captured within the EHR, provides high statistical power, and reflects patient- and family-centered priorities (4, 96–98). Reducing LOS is also a critical operational and financial metric for hospitals (16, 98, 99). Our measure of hospital LOS conservatively ranks deaths as long hospital stays, partially on the basis of our prior work showing that this approach avoids the selection bias or informative censoring associated with other methods of handling death in LOS analyses (100) and that patients’ and families’ considerations of tolerable amounts of time spent in the hospital depend on whether the patient survives (101, 102).

Hospital LOS is defined as starting from the time of patient enrollment. We chose enrollment rather than hospital admission on the basis of our prior work showing biases attributable to “immutable time”—that is, time in the hospital preceding deployment of an intervention that cannot be affected by the intervention (103). In primary analyses, death is ranked at the longest end of the LOS distribution. Sensitivity analyses assess how the results may change with different rankings of death (100)—in this case, by ranking death at the 75th, 85th, and 95th percentiles of the LOS distribution.

Secondary Outcomes

Our secondary process and clinical outcomes include palliative care consults, withdrawal of life support, ICU LOS, and hospital mortality and discharge disposition (Table 2). Most secondary outcomes are collected from the EHR, except for a nursing assessment of the end-of-life experience among enrolled patients who die in the hospital. The widely-used Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire has been validated among a diverse critically ill population and has been adapted and tested for nurse completion (104–107). The primary bedside nurse at the time of a patient’s death is invited via e-mail within 48 hours to complete the single-item version of the Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire (108) using the Research Electronic Data Capture platform (109).

Table 2.

Secondary process and outcome measures

| Outcome Measure | Variable Definition and Coding |

|---|---|

| Change in code status | Categorical: no change, new limitations on life support (e.g., DNAR, DNI), or discontinued limitations on life support |

| Initiation of additional forms of life support (e.g., acute dialysis, gastrostomy tube) | Binary; yes if CPT code 90935, 90937, 49440, 49441, or 43830 |

| Palliative care consult | Binary; yes if palliative care consult order |

| Time to palliative care consult | Continuous (h); time starts at enrollment |

| Palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation | Binary; yes if time of comfort-care order* precedes time of hospital death |

| Receipt of CPR | Binary; yes if CPT code 92950 |

| ICU mortality | Binary; yes if death occurred in the ICU or within 1 d of transfer out of ICU |

| ICU length of stay | Continuous (h); time starts at enrollment |

| ICU readmission | Binary; yes if readmitted to any ICU during same hospital encounter |

| Duration mechanical ventilation | Continuous (h); time starts at enrollment |

| Time to withdrawal of life support | Continuous (h); time starts at enrollment and ends at time of comfort-care order |

| Hospital discharge disposition | Categorical |

| Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire (1 item)† | Continuous; nurse-reported postmortem |

| 30-d hospital readmission‡ | Count |

| 30-d all-cause mortality§ | Binary; time starts at enrollment |

| 90-d all-cause mortality§ | Binary; time starts at enrollment |

| 180-d all-cause mortality§ | Binary; time starts at enrollment |

Definition of abbreviations: CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; DNAR = do not attempt resuscitation; DNI = do not intubate; ICU = intensive care unit.

Sensitivity 85.7% among 112 cases with palliative withdrawal of mechanical ventilation across participating ICUs.

“Overall, how would you rate the quality of the patient’s dying?” (score ranges from 0 = terrible experience to 10 = almost perfect experience) (102).

Includes admission to any Atrium Health acute care hospital.

Date of death determined from the electronic health record primarily and Social Security Death Index database secondarily (119).

Study Analyses

Primary Analytic Approaches

We will use the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach for all primary and main secondary analyses of the effectiveness of each intervention, such that all eligible patient encounters will be evaluated, regardless of clinician adherence to the EHR queries during the intervention phase. Because of anticipated skewness of the LOS distribution, we anticipate transforming to its log value before analysis. On the basis of data from participating ICUs during 2016, we anticipate the eligible cohort for this trial will have a mortality rate around 30%. With this high mortality rate, ranking death at or near the longest LOS produces a distribution of the primary outcome with a large spike at the end of the right skewed tail that is not mitigated by taking the log value of LOS. Thus, we will analyze the primary outcome using simultaneous quantile regression at the 20th, 30th, 40th, 50th, 60th, and 70th percentiles (110). This quantile-regression approach is robust because it makes no distributional assumptions (111). Testing above the 70th quantile is unnecessary if roughly 30% of patients die. This approach can efficiently identify plausible intervention effects by enabling a joint test of the overall significance across all quantiles, such that the null hypothesis is that there is no effect of treatment at any of the quantiles (112). In addition, this approach provides effect estimates at each individual quantile, about which we will construct 95% confidence intervals using bootstrapping. For the three planned comparisons (intervention A vs. control; intervention B vs. control; interventions A + B vs. control), we will adjust significance levels for multiple comparisons using the Holm method (113).

To augment precision in estimating treatment effects in this stepped-wedge cluster trial, primary analyses will be conducted with adjustment for prespecified patient- and encounter-level factors that exist before randomization (Table E2), so long as there is not substantial missingness in these factors (114, 115). Unadjusted analyses will also be reported. We will include fixed effects for clinician, hospital cluster, and time (69, 116). We will also include “time from enrollment” as a patient-level covariate to account for the possible differences in outcomes related to natural illness progression during a hospitalization that may influence processes of care (e.g., more family meetings), independently of any effect of the interventions or of calendar time. In preparing our final model, we will evaluate whether three different interaction terms change our results. First, we will include an interaction term for cluster and time to account for the possibility that the time effect might not be the same for all clusters. Second, we will investigate the variation in treatment effect across hospital clusters by including an interaction term between the intervention and cluster. Third, because of the “factorial” stepped-wedge design, we will test for the interaction between interventions A and B (117).

Because of the delay (a minimum of 2 h for patients enrolled at 12:00 up to a maximum of 20 h for patients enrolled at 18:00) between eligibility determination (when the intervention queries are available in the EHR for completion) and initiation of the clinician reminder alerts at 14:00 if queries are not completed, it is possible that clinicians will never receive alerts for some enrolled patients (i.e., those who die in the ICU, are no longer receiving mechanical ventilation, or are discharged from the ICU between enrollment and 14:00). Because active-alert reminders could plausibly increase adherence to (and therefore, potential effectiveness of) the interventions, we will perform a modified ITT analysis among patients who remained eligible through 14:00 after enrollment. Because all intervention-phase patient encounters included in this secondary analysis would have been subject to at least one active clinician alert, this analysis examines what the effect of the intervention(s) would be if active alerting were universal.

Analyses Accounting for Nonadherence

Because ICU clinicians may bypass the EHR alerts, there may be differences between the interventions’ effectiveness (i.e., effects among all patients to whom the interventions are targeted) and efficacy (i.e., effects among patients whose clinicians adhere to the interventions). Therefore, we will evaluate efficacy in secondary analyses using complier-average-treatment-effect (CATE) methods (118–120). Unlike per-protocol analyses, CATE analyses are not biased by selection effects, and have been shown to be valid inferential approaches in stepped-wedge trials (121). These analyses use data on all participants in the primary analytic sample and model the randomization arm as an instrumental variable to conduct an instrumental-variable quantile-regression analysis for the effect of the interventions on the median LOS (122). In sensitivity analyses, we will also explore effects on the 75th and 90th percentiles of the primary outcome distribution with fixed effects for cluster and time.

Analyses of Potential Effect Modifiers

We will assess whether prespecified characteristics of patients (age, sex, presence of a cancer diagnosis, race, and ICU admission source) or clinicians (sex, specialty board certification, years in practice) modify the sizes of the effects of each intervention on the primary outcome by conducting stratified analyses. If differences appear, we will formally evaluate for effect modification by testing the significance of statistical interaction terms between the potential effect modifier and the study phase (control, intervention A, intervention B, or combined) on the primary outcome.

Approach to Missing Data

We do not anticipate substantial missing data because the primary outcome and most secondary outcomes will be obtained or calculated from the hospitals’ routinely collected data in the EHR. Nonetheless, we will explore and potentially adjust for missing values using pattern-mixture methods in secondary analyses (123, 124).

Statistical Power Calculations

On the basis of pretrial data in 2016 across all participating ICUs, we estimate that approximately 4,750 patients will be eligible for inclusion during the 33-month trial period. We found that such patients had a mean total hospital LOS of 16.2 days (standard deviation, 11.8 d) and a median hospital LOS of 12.6 days, and we found that 31.5% died in the hospital. Ranking deaths at the longest LOS changes the mean and median to 28.0 days and 22.4 days, respectively. Using the conservative assumptions of intraclass correlations of patient outcomes of up to ρ = 0.10 within clinicians and ρ = 0.05 within ICUs, and conservatively estimating that our actual enrollment may lag our projections by as much 25% (i.e., 3,500–3,600 patients), the minimal detectable difference in the primary outcome between either intervention and control corresponds to a 13.4% decrease in the median hospital LOS (or roughly 3 d). Our design also provides at least 80% power to detect an additive effect of interventions A and B (i.e., that the two interventions combined will produce at least twice the effect of either intervention alone). Because these power calculations did not adjust for patient-level covariates, the true minimal detectable difference may be smaller.

Interim Analysis and Safety Monitoring

We convened a Data and Safety Monitoring Board comprising experts in critical care, palliative care, and biostatistics to help monitor and address anticipated and unforeseen risks arising during the study. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board and study investigators agreed not to establish formal stopping rules, given that most deaths are likely to reflect goal-concordant care, but we are monitoring time to withdrawal of life support and 30-, 90-, and 180-day all-cause mortality rates using the EHR or Social Security Death Index database (125) as safety endpoints to assess for persistent differences between arms over time. There will be one planned, blinded interim analysis of the primary outcome and these safety endpoints after approximately two-thirds of patients have been enrolled to enable sufficient accrual and follow-up in each intervention arm for comparison with the control.

Discussion

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to acknowledge in this highly pragmatic trial with EHR-based interventions. First, a fundamental challenge of pragmatic trials is designing a flexible yet effective intervention-adherence plan to enhance fidelity (126). To address this, we have designed a systematic approach of multifaceted clinician reminders for timely completion of the EHR intervention(s), and we will perform a secondary efficacy (CATE) analysis among patients who would have received the intervention if assigned to it. Second, the interventions used in this trial may be less effective among clinicians who experience distress about or lack skills in engaging families in goals-of-care discussions (127, 128). In keeping with our pragmatic approach, we did not employ resource-intensive clinician education (30, 129) or collect self-reported characteristics. However, such clinician-level effects will be estimated in the primary ITT analysis and secondary effect-modification analyses. Finally, we are not capturing patient- and family-reported outcomes, largely because of infeasibility in a trial conducted with a waiver of informed consent, the large sample size, and the anticipated nonrandom missingness and nonresponse bias.

Potential Outcomes and Conclusions

The two interventions being tested in this trial build from a strong evidence base for changing clinicians’ behaviors and represent the first applications of these approaches for promoting palliative approaches to care for patients in whom such care is recommended. As a randomized trial within one of the nation’s largest integrated health systems, the PONDER-ICU trial is powered to detect differences in outcomes that are important to patients, families, hospitals, and payers. Most importantly, the simple EHR-based interventions being tested are highly scalable, thereby facilitating widespread adoption if they are shown to be effective.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

PONDER-ICU Investigative Team: University of Pennsylvania: Katherine R. Courtright, M.D., M.S. (Co–Principal Investigator); Scott D. Halpern, M.D., Ph.D. (Co–Principal Investigator); Erich M. Dress, M.P.H., M.B.E.; Brian A. Bayes, M.S.; Marzana Chowdhury, Ph.D.; Michael O. Harhay, Ph.D.; and Dylan S. Small, Ph.D.; University of Southern California: Jason N. Doctor, Ph.D.; University of Toronto: Michael E. Detsky, M.D., M.S.; Atrium Health: Jaspal Singh, M.D., M.H.A., M.H.S. (site Principal Investigator); Henry L. Burke, M.D.; Erica Frechman, M.S.N.; Michael B. Green, M.D., M.B.A.; Jennifer Hall, R.N., C.C.R.N.-E.; Toan Huynh, M.D.; Jessica Kearney-Bryan, R.N., B.S.N., C.C.R.N.; Amanda Kerr, R.N.; and Sara Tucker, B.S.N., M.B.A., R.N., C.C.N.R.-E.; Atrium Health Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation: Timothy Hetherington, M.S., and Whitney Rossman, M.S., P.M.P.; Atrium Health Information and Analytic Services: William Hofmann, M.Ed.; Stacie Houghton, B.S.; Lindsay Plickert, B.S.N., R.N., C.C.R.N.-K.; Timm Tanner, B.S.; and D. Matthew Sullivan, M.D.; Atrium Health Clinical Centers: Carolinas HealthCare System Blue Ridge–Morganton, Morganton, North Carolina; Carolinas Medical Center (CMC), Charlotte, North Carolina; Cleveland, Shelby, North Carolina; Cabarrus, Concord, North Carolina; CMC-Mercy, Charlotte, North Carolina; Pineville, Charlotte, North Carolina; University City, Charlotte, North Carolina; Union, Monroe, North Carolina; Lincoln, Lincolnton, North Carolina; and Stanly, Albemarle, North Carolina; Data and Safety Monitoring Board: Michael Elliott, Ph.D. (Chair); Judy E. Davidson, D.N.P., R.N., F.C.C.M., F.A.A.N.; and Judith Nelson, M.D., J.D.

Footnotes

Supported by the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. The views expressed in this article do not communicate an official position of the Donaghue Foundation.

Author Contributions: Study design and protocol: K.R.C., E.M.D., J.S., B.A.B., M.C., D.S.S., T. Hetherington, L.P., M.E.D., J.N.D., M.O.H., H.L.B., M.B.G., T. Huynh, D.M.S., and S.D.H. Wrote and/or edited portions of the manuscript: K.R.C., E.M.D., J.S., M.C., and S.D.H. Provided critical feedback and revisions of the final manuscript: K.R.C., E.M.D., J.S., B.A.B., M.C., D.S.S., T. Hetherington, L.P., M.E.D., J.N.D., M.O.H., H.L.B., M.B.G., T. Huynh, D.M.S., and S.D.H.

A complete list of PONDER-ICU Investigative Team members may be found before the beginning of the References.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Erica Frechman, Jennifer Hall, Jessica Kearney-Bryan, Amanda Kerr, Sara Tucker, Whitney Rossman, William Hofmann, Stacie Houghton, Timm Tanner, Michael Elliott, Judy E. Davidson, and Judith Nelson

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, Barnato AE, Gawande AA, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, Cenzer IS, Boscardin J, Fisher J, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1277–1285. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Care at the End of Life, Institute of Medicine Fields MJ, Cassel CK.editors. Approaching death, improving care at the end of life Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 5.People’s memo to politicians: this is not your fight Time Magazine 2005 April 4 [accessed 2016 Jul 26]. Available from: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1042447,00.html

- 6.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright AA, Zhang BH, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. FAMIREA Study Group. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpern SD, Becker D, Curtis JR, Fowler R, Hyzy R, Kaplan LJ, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/American Association of Critical-Care Nurses/American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine policy statement: the Choosing Wisely® top 5 list in Critical Care Medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:818–826. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1317ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JE, Bassett R, Boss RD, Brasel KJ, Campbell ML, Cortez TB, et al. Improve Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit Project. Models for structuring a clinical initiative to enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: a report from the IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU) Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1765–1772. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8ad23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, Haas CE, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [Published erratum appears in Crit Care Med 2008;36:1699.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, Dugan DO, Blustein J, Cranford R, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, Massaro AF, Wallace RF, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, Nielsen EL, Paul S, Lahdya AZ, et al. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Downey L, Dotolo D, Shannon SE, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:51–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White DB, Angus DC, Shields A-M, Buddadhumaruk P, Pidro C, Paner C, et al. A randomized trial of a family-support intervention in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua M, Li G, Blinderman C, Wunsch H. Estimates of the need for palliative care consultation across United States intensive care units using a trigger-based model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:428–436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright AA, Mack JW, Kritek PA, Balboni TA, Massaro AF, Matulonis UA, et al. Influence of patients’ preferences and treatment site on cancer patients’ end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:4656–4663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen B, Salsberg E. Rensselaer, NY: Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, University at Albany; 2002. The supply, demand and use of palliative care physicians in the United States: a report prepared for the Bureau of HIV/AIDS, Health Resources and Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumanovsky T, Rogers M, Spragens LH, Morrison RS, Meier DE. Impact of staffing on access to palliative care in US hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:998–999. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lupu D American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, Hutchings M, Kavanagh J, Geerse OP, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:751–759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Waters A, Laidsaar-Powell RC, O’Brien A, Boyle F, et al. Evaluation of a novel individualised communication-skills training intervention to improve doctors’ confidence and skills in end-of-life communication. Palliat Med. 2013;27:236–243. doi: 10.1177/0269216312449683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moorman SM, Carr D. Spouses’ effectiveness as end-of-life health care surrogates: accuracy, uncertainty, and errors of overtreatment or undertreatment. Gerontologist. 2008;48:811–819. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seckler AB, Meier DE, Mulvihill M, Paris BE. Substituted judgment: how accurate are proxy predictions? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:92–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-2-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, Weissfield LA, White DB. Surrogate decision makers’ interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:360–366. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emanuel EJ, Ubel PA, Kessler JB, Meyer G, Muller RW, Navathe AS, et al. Using behavioral economics to design physician incentives that deliver high-value care. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:114–119. doi: 10.7326/M15-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpern SD. Using default options and other nudges to improve critical care. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:460–464. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheunemann LP, Arnold RM, White DB. The facilitated values history helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:480–486. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0710CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life: initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients. Addressing the “elephant in the room”. JAMA. 2000;284:2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, Nielsen EL, Zatzick D, Curtis JR. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139:795–801. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quill CM, Ratcliffe SJ, Harhay MO, Halpern SD. Variation in decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapies in US ICUs. Chest. 2014;146:573–582. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hart JL, Harhay MO, Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Quill CM, Halpern SD. Variability among US intensive care units in managing the care of patients admitted with preexisting limits on life-sustaining therapies. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hua M, Halpern SD, Gabler NB, Wunsch H. Effect of ICU strain on timing of limitations in life-sustaining therapy and on death. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:987–994. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garland A, Connors AF. Physicians’ influence over decisions to forego life support. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1298–1305. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Cuschieri J, Hallman MR, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Differences in end-of-life care in the ICU across patients cared for by medicine, surgery, neurology, and neurosurgery physicians. Chest. 2014;145:313–321. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danis M, Mutran E, Garrett JM, Stearns SC, Slifkin RT, Hanson L, et al. A prospective study of the impact of patient preferences on life-sustaining treatment and hospital cost. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1811–1817. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schenker Y, Tiver GA, Hong SY, White DB. Association between physicians’ beliefs and the option of comfort care for critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1607–1615. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brush DR, Rasinski KA, Hall JB, Alexander GC. Recommendations to limit life support: a national survey of critical care physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:633–639. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0354OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, You JJ, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:778–787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gay EB, Pronovost PJ, Bassett RD, Nelson JE. The intensive care unit family meeting: making it happen. J Crit Care. 2009;24:629, e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR. Prognostication during physician-family discussions about limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:442–448. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254723.28270.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cox CE, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray AL, et al. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2888–2894; quiz 2904. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab86ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White DB, Malvar G, Karr J, Lo B, Curtis JR. Expanding the paradigm of the physician’s role in surrogate decision-making: an empirically derived framework. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:743–750. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized-patients: the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [Published erratum appears in JAMA 275:1232.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halpern SD. Shaping end-of-life care: behavioral economics and advance directives. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:393–400. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1322403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1340–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gorin M, Joffe S, Dickert N, Halpern S. Justifying clinical nudges. Hastings Cent Rep. 2017;47:32–38. doi: 10.1002/hast.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nuffield Council on Bioethics. London, UK: Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 2007. Public health ethical issues. Available from: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section/section_8/level8_8.php. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Small DS, Wynne C, Zhu J, Yang L, et al. Using active choice within the electronic health record to increase influenza vaccination rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:790–795. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takvorian SU, Ladage VP, Wileyto EP, Mace DS, Beidas RS, Shulman LN, et al. Association of behavioral nudges with high-value evidence-based prescribing in oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1104–1106. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, Friedberg MW, Persell SD, Goldstein NJ, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:562–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel MS, Day SC, Halpern SD, Hanson CW, Martinez JR, Honeywell S, Jr, et al. Generic medication prescription rates after health system-wide redesign of default options within the electronic health record. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:847–848. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dainty KN, Scales DC, Brooks SC, Needham DM, Dorian P, Ferguson N, et al. A knowledge translation collaborative to improve the use of therapeutic hypothermia in post-cardiac arrest patients: protocol for a stepped wedge randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2011;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mdege ND, Man M-S, Taylor CA, Torgerson DJ. Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:936–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kohn R, Madden V, Kahn JM, Asch DA, Barnato AE, Halpern SD, et al. Diffusion of evidence-based intensive care unit organizational practices: a state-wide analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:254–261. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201607-579OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilson ME, Samirat R, Yilmaz M, Gajic O, Iyer VN. Physician staffing models impact the timing of decisions to limit life support in the ICU. Chest. 2013;143:656–663. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garland A, Gershengorn HB. Staffing in ICUs physicians and alternative staffing models. Chest. 2013;143:214–221. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cambell MJ, Walter SJ. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. How to design, analyse and report cluster randomised trials in medicine and health related research. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hemming K, Taljaard M, McKenzie JE, Hooper R, Copas A, Thompson JA, et al. Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2018;363:k1614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hemming K, Taljaard M, Grimshaw J. Introducing the new CONSORT extension for stepped-wedge cluster randomised trials. Trials. 2019;20:68. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3116-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Girling AJ, Hemming K. Statistical efficiency and optimal design for stepped cluster studies under linear mixed effects models. Stat Med. 2016;35:2149–2166. doi: 10.1002/sim.6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Tulsky JA. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, et al. Half the family members of intensive care unit patients do not want to share in the decision-making process: a study in 78 French intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1832–1838. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139693.88931.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fan E, Gifford JM, Chandolu S, Colantuoni E, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. The functional comorbidity index had high inter-rater reliability in patients with acute lung injury. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groll DL, Heyland DK, Caeser M, Wright JG. Assessment of long-term physical function in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients: comparison of the Charlson Comorbidity Index and the Functional Comorbidity Index. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:574–581. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000223220.91914.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, Martin-Lefevre L, Pons B, Boulet E, et al. Initiation strategies for renal-replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pittet D, Thievent B, Wenzel RP, Li N, Gurman G, Suter PM. Importance of pre-existing co-morbidities for prognosis of septicemia in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19:265–272. doi: 10.1007/BF01690546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tran DD, Groeneveld AB, van der Meulen J, Nauta JJ, Strack van Schijndel RJ, Thijs LG. Age, chronic disease, sepsis, organ system failure, and mortality in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:474–479. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poses RM, McClish DK, Smith WR, Bekes C, Scott WE. Prediction of survival of critically ill patients by admission comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:743–747. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Detsky ME, Harhay MO, Bayard DF, Delman AM, Buehler AE, Kent SA, et al. Six-month morbidity and mortality among intensive care unit patients receiving life-sustaining therapy: a prospective cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1562–1570. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-875OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade D, Schwarz N, Stone AA. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science. 2006;312:1908–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1129688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schkade DA, Kahneman D. Does living in California make people happy? A focusing illusion in judgments of life satisfaction. Psychol Sci. 1998;9:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Turnbull AE, Krall JR, Ruhl AP, Curtis JR, Halpern SD, Lau BM, et al. A scenario-based, randomized trial of patient values and functional prognosis on intensivist intent to discuss withdrawing life support. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1455–1462. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turnbull AE, Hayes MM, Brower RG, Colantuoni E, Basyal PS, White DB, et al. Effect of documenting prognosis on the information provided to ICU proxies: a randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:757–764. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.O’Connor SD, Sodickson AD, Ip IK, Raja AS, Healey MJ, Schneider LI, et al. Journal club: requiring clinical justification to override repeat imaging decision support. Impact on CT use. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:W482–W490. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jerdee TH, Rosen B. Effects of opportunity to communicate and visibility of individual decisions on behavior in the common interest. J Appl Psychol. 1974;59:712–716. [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Cremer D, Bakker M. Accountability and cooperation in social dilemmas: the influence of others’ reputational concerns. Curr Psychol. 2003;22:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lerner JS, Tetlock PE. Accounting for the effects of accountability. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:255–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. Protection of human subjects: general requirements for informed consent. 45 CFR 46.116(d) [accessed 2016 Dec 9]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.116. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, Ritchie CS, Furman CD, Rosenfeld K, et al. A nationwide VA palliative care quality measure: the family assessment of treatment at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:68–75. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holloway RG, Quill TE. Mortality as a measure of quality: implications for palliative and end-of-life care. JAMA. 2007;298:802–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cassel JB, Kerr K, Pantilat S, Smith TJ. Palliative care consultation and hospital length of stay. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:761–767. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, Morrison RS, Normand C. Using length of stay to control for unobserved heterogeneity when estimating treatment effect on hospital costs with observational data: issues of reliability, robustness, and usefulness. Health Serv Res. 2016;51:2020–2043. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin W, Halpern SD, Kerlin MP, Small DS. A “placement of death” approach for studies of treatment effects on ICU length of stay. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26:292–311. doi: 10.1177/0962280214545121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Auriemma CL, Lyon SM, Strelec LE, Kent S, Barg FK, Halpern SD. Defining the medical intensive care unit in the words of patients and their family members: a freelisting analysis. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24:e47–e55. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lyon SM, Auriemma CL, Hilbert C, Cooney E, Sterlec L, Kent S, et al. Defining patient- and surrogate-centered outcomes for critical care research [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:A2181. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harhay MO, Ratcliffe SJ, Halpern SD. Measurement error due to patient flow in estimates of intensive care unit length of stay. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1389–1395. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hodde NM, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Factors associated with nurse assessment of the quality of dying and death in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1648–1653. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133018.60866.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127:1775–1783. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mularski R, Curtis JR, Osborne M, Engelberg RA, Ganzini L. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, Ganzini L, Curtis JR. Quality of dying in the ICU: ratings by family members. Chest. 2005;128:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gould W. Interquantile and simultaneous-quantile regression. Stata Tech Bull. 1997;7:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee AH, Fung WK, Fu B. Analyzing hospital length of stay: mean or median regression? Med Care. 2003;41:681–686. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062550.23101.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tokdar ST, Kadane JB. Simultaneous linear quantile regression: a semiparametric Bayesian approach. Bayesian Anal. 2012;7:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med. 2002;21:2917–2930. doi: 10.1002/sim.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Committee for Propietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) Points to consider on adjustment for baseline covariates. Stat Med. 2004;23:701–709. doi: 10.1002/sim.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ji XY, Fink G, Robyn PJ, Small DS. Randomization inference for stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials: an application to community-based health insurance. Ann Appl Stat. 2017;11:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lyons VH, Li L, Hughes JP, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Proposed variations of the stepped-wedge design can be used to accommodate multiple interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;86:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:444–455. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cheng J, Small DS, Tan Z, Ten Have TR. Efficient nonparametric estimation of causal effects in randomized trials with noncompliance. Biometrika. 2009;96:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Small DS, Ten Have T, Rosenbaum PR. Randomization inference in a group–randomized trial of treatments for depression. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gruber JS, Arnold BF, Reygadas F, Hubbard AE, Colford JM., Jr Estimation of treatment efficacy with complier average causal effects (CACE) in a randomized stepped wedge trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:1134–1142. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chernozhukov V, Hansen C. Instrumental variable quantile regression: a robust inference approach. J Econom. 2008;142:379–398. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Guo WS, Ratcliffe SJ, Ten Have TT. A random pattern-mixture model for longitudinal data with dropouts. J Am Stat Assoc. 2004;99:929–937. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hall SM, Delucchi KL, Velicer WF, Kahler CW, Ranger-Moore J, Hedeker D, et al. Statistical analysis of randomized trials in tobacco treatment: longitudinal designs with dichotomous outcome. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:193–202. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Quinn J, Kramer N, McDermott D. Validation of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI): an important readily-available outcomes database for researchers. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Courtright KR, Halpern SD. Pragmatic trials and the evolution of serious illness research. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1079–1080. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kangovi S, Asch DA. Behavioral phenotyping in health promotion: embracing or avoiding failure. JAMA. 2018;319:2075–2076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, Saulsgiver K, Harhay MO, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Heterogeneity in the effects of reward- and deposit-based financial incentives on smoking cessation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:981–988. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0108OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, Smith G, Paladino J, Lipsitz S, et al. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009032. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]