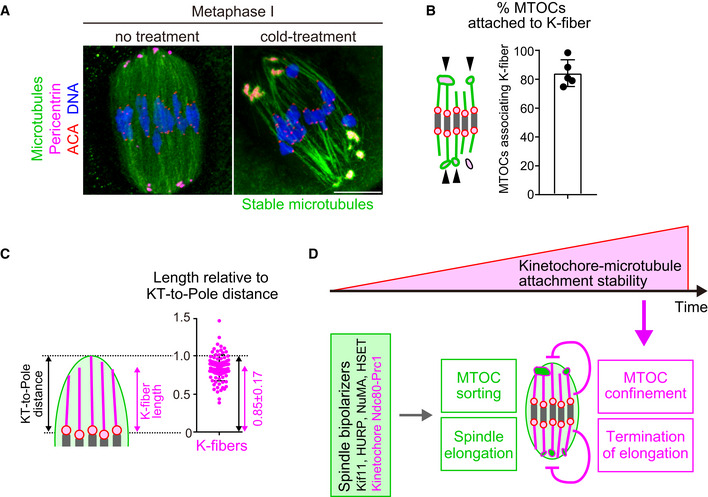

Figure 5. Model showing how kinetochore–microtubule attachments contribute to acentrosomal spindle bipolarization.

- K‐fibers are connected to MTOCs and extend to spindle poles. Oocytes 6 hours after NEBD were fixed following cold treatment. Microtubules (α‐tubulin, green), MTOCs (pericentrin, magenta), kinetochores (ACA, red), and DNA (Hoechst333342) are shown. Five oocytes from two independent experiments were analyzed. Scale bar, 10 μm.

- A majority of MTOCs are attached to K‐fibers. The volumes of individual MTOCs were measured after 3D reconstruction. The sum volume of MTOCs attached to K‐fibers relative to the total volume of MTOCs was calculated for each oocyte (n = 5 oocytes from two independent experiments). Means and SD are shown.

- K‐fibers extend to spindle poles. The length of K‐fibers and distance between kinetochores and a spindle pole (KT‐to‐Pole distance) were measured. K‐fiber length relative to the KT‐to‐Pole distance was calculated (n = 90 K‐fibers of 5 oocytes from two independent experiments).

- Model summarizing the results of this study. In early phases of acentrosomal spindle assembly, spindle bipolarizers, including Kif11, HURP, NuMA, HSET, and the kinetochore Ndc80 complex that recruits Prc1, establish spindle bipolarity by promoting MTOC sorting and spindle elongation. Meanwhile, the stability of kinetochore–microtubule attachments gradually increases, depending on the dephosphorylation of kinetochore components including Ndc80. As spindle bipolarity is established, stable kinetochore–microtubule attachments spatially confine MTOCs at spindle poles and limit spindle elongation.

Source data are available online for this figure.