Abstract

Resurgence of a previously suppressed target behavior is common when reinforcement for a more recently reinforced alternative behavior is thinned. To better characterize such resurgence, these experiments examined repeated within-session alternative reinforcement thinning using a progressive-interval (PI) schedule with rats. In Experiment 1, a transition from a high rate of alternative reinforcement to a within-session PI schedule generated robust resurgence, but subsequent complete removal of alternative reinforcement produced no additional resurgence. Experiment 2 replicated these findings and showed similar effects with a fixed-interval (FI) schedule arranging similarly reduced session-wide rates of alternative reinforcement. Thus, the lack of additional resurgence following repeated exposure to the PI schedule was likely due to the low overall obtained rate of alternative reinforcement provided by the PI schedule, rather than to exposure to within-session reinforcement thinning per se. In both experiments, target responding increased at some point in the session during schedule thinning and continued across the rest of the session. Rats exposed to a PI schedule showed resurgence later in the session and after more cumulative alternative reinforcers than those exposed to an FI schedule. The results suggest the potential importance of further exploring how timing and change-detection mechanisms might be involved in resurgence.

Keywords: relapse, resurgence, alternative reinforcement, reinforcement thinning, lever pressing, rats

Differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) is among the most widespread and effective clinical interventions for the reduction of unwanted behavior (e.g., Higgins et al., 2008; Petscher et al., 2009; Tiger et al., 2008; Wacker et al., 2011). Often, DRA involves discontinuing reinforcement for an undesirable target behavior (i.e., extinction), while simultaneously reinforcing an alternative behavior. For example, in functional communication training (FCT) the reinforcer maintaining problem behavior is withheld and delivered instead for an appropriate communicative response (e.g., Carr & Durand, 1985).

Despite the efficacy of DRA-based interventions, the omission of alternative reinforcement can result in relapse (i.e., resurgence) of the target behavior (e.g., Lattal & St. Peter Pipkin, 2009; Marsteller & St. Peter, 2012; Silverman et al., 1999; Venniro et al., 2017; Volkert et al., 2009). Broadly, resurgence is defined as an increase in a previously suppressed behavior following a relative worsening of conditions for a more recently reinforced alternative behavior (e.g., Lattal et al., 2017; Shahan & Craig, 2017). A better understanding of the variables impacting the occurrence of resurgence could lead to improved clinical DRA-based treatments and could potentially provide more general insights about learning, adaptation, and decision-making (Greer & Shahan, 2019; Shahan et al., 2020; Shahan & Craig, 2017).

A typical experiment on resurgence typically includes three phases that roughly correspond to how a problem behavior might be treated in the clinic. In Phase 1, a target response is acquired under some schedule of reinforcement. The acquisition and subsequent maintenance of this target response mimics the reinforcement history of a problem behavior. Phase 2, which acts as the treatment phase, involves extinction of the target response and reinforcement for an alternative response (i.e., DRA). Finally, Phase 3 arranges extinction for both responses, which simulates the omission of alternative reinforcement and allows for examination of the resurgence effect. Resurgence is said to occur when target responding increases in this final phase relative to responding in the treatment phase.

Typically, DRA-based interventions like FCT initially employ a high rate of alternative reinforcement to ensure that the alternative response is acquired and that problem behavior is sufficiently reduced (e.g., Hanley et al., 2001; Roane et al., 2004; St. Peter, 2015). However, there are at least two potential problems associated with the use of high-rate alternative reinforcement. First, previous research with both animals and human participants has demonstrated that although high rates of alternative reinforcement are more effective at suppressing the target behavior, they also tend to generate more resurgence when subsequently omitted (Craig & Shahan, 2016; Craig et al., 2016; Leitenberg et al.,1975; Parry-Cruwys et al., 2011; Pritchard et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2017; Sweeney & Shahan, 2013; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2010). Second, high rates of alternative reinforcement may also be impractical to maintain as they could lead to undesirably high rates of alternative behavior (see Fisher et al., 1993; Hanley et al., 2001; Tiger et al., 2008).

Schedule thinning, in which the rate of alternative reinforcement is gradually reduced, provides a potential solution for both of these problems associated with high-rate alternative reinforcement (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2004, 2005). Both basic and applied experiments have shown that the magnitude of subsequent resurgence is reduced following alternative reinforcement thinning (e.g., Fuhrman et al., 2016; Schepers & Bouton, 2015; Sweeney & Shahan, 2013; Volkert et al., 2009; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012). However, a shortcoming of this strategy is that resurgence of problem behavior frequently occurs during schedule thinning procedures themselves (e.g., Briggs et al., 2018; Hagopian et al., 2011; Hanley et al., 2001). For example, Briggs et al. (2018) analyzed 25 different applications of schedule thinning during FCT and found that resurgence of destructive behavior occurred in 19 of 25 (76%) cases. Therefore, a question of interest is how best to thin alternative reinforcement schedules such that there is as little resurgence as possible during thinning. However, answering this question will require a better characterization of resurgence during alternative reinforcement thinning.

Basic experiments on alternative reinforcement thinning have generally reduced alternative reinforcement rates across successive sessions. For example, with one group of rats Sweeney and Shahan (2013) began Phase 2 with a variable-interval (VI) 10-s schedule for the alternative response. In each subsequent session the schedule was increased by 10 s such that by the final Phase 2 session the alternative schedule was VI 100 s. Similarly, after establishing the alternative response on a VI 10-s schedule for four sessions, Schepers and Bouton (2015) thinned alternative reinforcement by increasing the value of the VI schedule in each subsequent session by a factor of 4. Similar to the findings of Briggs et al. (2018), both of these studies showed that resurgence of target behavior occurred at some point during schedule thinning. Although such across-session decreases in alternative reinforcement provide demonstrations of resurgence during schedule thinning, they provide a relatively coarse-grain analysis of the phenomenon. Examinations of within-session decreases in alternative reinforcement rate might provide a richer analysis of resurgence induced by alternative-reinforcement thinning.

Thus far, only two studies have examined the impact of within-session decreases in alternative reinforcement rates on resurgence. Winterbauer and Bouton (2012) conducted experiments with rats in which alternative reinforcement rates were thinned during experimental sessions in several different ways. In Experiment 1, within-session thinning was arranged by cutting the reinforcement rate in half in the middle of each consecutive session (e.g., 3 reinforcers/min to 1.5 reinforcers/min, etc.) after a single session of a random-interval (RI) 20-s schedule of alternative reinforcement. Although the thinning group showed no additional resurgence after alternative reinforcement was removed during the extinction phase, during Phase 2 resurgence occurred following roughly 30-min of exposure to an RI 40-s alternative schedule. Subsequently, target responding continued to increase until the final thinning session in which the alternative schedule was changed to an RI 160-s. In Experiment 2, one group was a replication of the thinning group in Experiment 1, and the other group experienced gradual thinning each second, such that the reinforcement schedule was incremented by approximately 0.11 s each second. This ensured that by the end of each session both groups had experienced the same overall rate of reinforcement. Increases in target responding occurred to a similar degree in both groups as the schedules were made leaner. Experiment 3 produced this same general finding when the gradual thinning was arranged using both RI and fixed-interval (FI) schedules. However, in all of these experiments, rats were exposed to only one full session of a relatively rich alternative schedule in Phase 2 before schedule thinning began. As a result, target response rates remained relatively high when thinning began. As noted above, in the clinic alternative reinforcement thinning typically begins only after target responding has been effectively reduced following more extended exposure to high-rate alternative reinforcement (e.g., Hanley et al., 2001; Roane et al., 2004, St. Peter, 2015).

The second study to examine within-session alternative reinforcement thinning assessed resurgence in both children and pigeons when a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule was imposed on the alternative response within sessions (Ho et al., 2018). At the level of session-wide response rates, Ho et al. found modest evidence for resurgence generated by the PR schedule with both children and pigeons. In addition, pooled across sessions of exposure to the PR schedule, they reported that there was a positive correlation between the absolute number of target responses within obtained inter-reinforcer intervals (IRI) and the duration of those IRIs. This finding is comparable to that of Lieving and Lattal (2003) with 2 of 3 pigeons in which the absolute number of target responses within IRIs was a positive function of IRI duration during an abrupt 12-fold decrease in alternative reinforcement rate arranged by a VI schedule. Based on these findings, Ho et al. (2018) suggested that resurgence was more likely during longer periods of non-reinforcement. However, the fact that both Ho et al. and Lieving and Lattal based their analyses on the number of target responses as a function of the IRI duration introduces some interpretative uncertainty. Longer IRIs provide a longer sampling period than shorter IRIs, and thus, a greater number of target responses would be expected during longer alternative IRIs even if target responding emerged at point and remained roughly constant across IRIs in the thinning progression. Indeed, the fact that Ho et al. observed no correlation between target response rates and IRI duration suggests that the positive relation between number of target responses and IRI duration could be an artifact of the longer sampling periods. Thus, although it seems likely that resurgence results from exposure to increasingly long periods of non-reinforcement, the data presented in Ho et al. do not allow one to clearly assess when resurgence emerged during the schedule thinning sequence. Finally, Ho et al. used a progressive ratio schedule, and as a result, the obtained IRIs were highly dependent upon alternative response rates, and thus poorly controlled. As noted by Ho et al., “the rate and distribution of alternative reinforcers during experimental conditions could be better controlled by using progressive-interval schedules than PR schedules”.

Thus, in order to begin to better characterize resurgence during within-session alternative reinforcement thinning, Experiment 1 examined resurgence during exposure to a within-session progressive-interval (PI) schedule of alternative reinforcement. The PI schedule of alternative reinforcement was introduced after target responding had been reduced to low levels by extinction and a high rate of alternative reinforcement. In addition to examining resurgence of target responding at a session-wide level, we also examined target response rates as a function of the increasing IRIs arranged by the PI progression and we employed cumulative records to more fully characterize when target responding increased during that progression.

EXPERIMENT 1

Method

Subjects

Five experimentally naïve male Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Portage MI) were used in the experiment. Rats were 71–90 days old upon arrival and were maintained at 80% of their free-feeding weights. Rats were individually housed with free access to water in a temperature-controlled colony room with a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). Care of animals and all procedures below were approved by Utah State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Five identical modular Med Associates (St. Albans, VT) operant chambers were used in the experiment. These chambers measured 30 cm × 24 cm × 21 cm and were housed in sound and light attenuating cubicles. Each chamber had aluminum panels on the front and back walls, with Plexiglas walls on each side and the ceiling. On the front panel of each chamber were two retractable levers each with identical stimulus lights above them. Levers were positioned equidistantly on either side of a centered food pellet receptacle which was illuminated when delivering 45-mg food pellets (Bio Serv, Flemington, NJ). A house light on the opposite end of the chamber was used for general illumination. The timing of experimental events and data collection were controlled by Med-PC IV (Med Associates) software run on a computer in an adjacent control room.

Procedure

Experimental sessions took place once daily at approximately the same time each day during the light cycle. Sessions in all phases were 35 min long excluding time for reinforcement delivery during which the house light was turned off and the receptacle was illuminated for 4 s. During this time, any responses made to the levers had no consequences.

Training.

Prior to the start of Phase 1, rats were trained to consume food pellets from the food aperture for 3 sessions. During these training sessions, the levers were retracted, and the house light and stimulus lights remained off. Food pellets were delivered response-independently according to a variable-time (VT) 60-s schedule with 10 intervals generated by the constant-probability progression of Fleshler and Hoffman (1962). Each food delivery consisted of a single pellet accompanied by an audible click and illumination of the feeder. The day following the final magazine training session, a single session for response acquisition was conducted. This session began with illumination of the house light and insertion of the target lever (left-right counterbalanced across subjects), with the stimulus light above it also illuminated. The first time the target lever was pressed, a food pellet was delivered immediately, and subsequently target lever-presses produced reinforcement according to a VI 10-s schedule.

Phase 1 – Baseline.

As in training, the target lever was inserted and the house light and the light above the target lever were illuminated. Responses to the target lever produced food pellets according to a VI 30-s schedule of reinforcement. This phase lasted for 30 sessions.

Phase 2 – FI-10 DRA.

Sessions during this phase began as in baseline sessions, with the exception that now both levers were inserted into the chambers, and both lever lights were illuminated. The target lever no longer produced food pellets (i.e., extinction), and the alternative lever produced food pellets according to an FI 10-s schedule. The FI schedule was used to ensure that rats did not experience programmed alternative IRIs longer than 10 s until the start of the subsequent thinning phase. This phase lasted for 15 sessions to ensure target response rates were sufficiently reduced prior to thinning.

Phase 3 – PI alternative reinforcement thinning.

Sessions during this phase began as in Phase 2, but the schedule of reinforcement for the alternative response was changed to a PI 10-s schedule with a 20% step size. That is, after the receipt of each reinforcer, the subsequent IRI increased by 20% of its current value (i.e., the first interval was 10 s, the second 12 s, etc.). Intervals ranged from 10 s to approximately 320 s by the end of each 35 min session. Importantly, at the beginning of each subsequent session, the PI schedule was reset to its starting value of 10 s, and the gradual thinning across the session was repeated in each session. This phase lasted 16 sessions until rates of target behavior began to stabilize.

Phase 4- Extinction.

Sessions during this phase began exactly as in the prior phase, but now lever presses to both levers had no consequences (i.e., extinction). All other stimulus conditions remained the same as before. This phase lasted for 5 sessions.

Results

Figure 1 shows target response rates in the final three sessions of Phase 1, and both target and alternative responding in all subsequent sessions of the experiment for individual rats. Despite some variability across subjects in response rates during baseline, introduction of the DRA contingency in Phase 2 decreased target behavior to low levels by the end of the phase for all subjects. All rats acquired the alternative response, and by the end of Phase 2 all had allocated the vast majority of their responding to the alternative lever (see Table 1 for further detail). Upon the transition from the FI 10-s schedule of alternative reinforcement to the PI schedule, all rats showed an increase in target responding (i.e., resurgence) compared to responding in the last session of Phase 2 (see Table 1). A paired samples t-test conducted on target response rates in the final session of Phase 2 and the first session of Phase 3 confirmed that this increase was statistically significant, t(4) = 4.69, p = .009, d = 2.91 (M P2 = 1.25, M P3 = 7.2). Following the initial increase in target responding upon introduction of the PI schedule, target response rates decreased for all rats across repeated sessions of exposure to the PI schedule in Phase 3. This decrease across sessions was significant as confirmed by a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), F(15, 60) = 4.70, p < .001, ηp2 = .54. In addition, four of five rats showed an initial increase in alternative response rate upon introduction of the PI schedule, and by the end of Phase 3, three of five rats showed a decrease in alternative behavior compared to the last session of Phase 2 (see Table 1). In the final resurgence test in Phase 4 in which alternative reinforcement was completely removed, there was little change in the rates of target behavior as compared to the end of the previous PI thinning phase. A paired samples t-test conducted on target response rates in the final session of Phase 3 and the first session of Phase 4 revealed no statistical difference in these two sessions, t(4) = 0.3, p = .78, d = .11 (M P3 = 3.4, M P4 = 3.56).

Figure 1.

Target and alternative response rates for individual subjects from the final 3 sessions of Phase 1 (Baseline) and all subsequent sessions of Experiment 1. Top and bottom panels display target and alternative responding, respectively. Different symbols represent individual subjects and are consistent across panels.

Table 1.

Response rates and obtained SR rates during the last three phases of Experiment 1.

| Last Session Phase 2 | First Session Phase 3 | Last Session Phase 3 | First Session Phase 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Alt | SR Rate | Target | Alt | SR Rate | Target | Alt | SR Rate | Target | Alt | |

| TN1 | 0.89 | 18.60 | 5.20 | 11.00 | 25.09 | 0.57 | 2.71 | 21.91 | 0.57 | 2.94 | 21.46 |

| TN2 | 1.46 | 37.51 | 5.60 | 6.71 | 23.91 | 0.57 | 4.17 | 13.00 | 0.57 | 4.11 | 11.20 |

| TN3 | 1.40 | 19.37 | 3.43 | 3.97 | 22.57 | 0.57 | 1.54 | 10.00 | 0.57 | 1.43 | 6.31 |

| TN4 | 1.91 | 24.23 | 5.37 | 9.06 | 29.11 | 0.57 | 4.03 | 19.09 | 0.57 | 6.11 | 11.51 |

| TN5 | 0.57 | 11.26 | 4.60 | 5.26 | 18.80 | 0.57 | 4.51 | 11.54 | 0.57 | 3.20 | 10.34 |

Note. All rates calculated as events/min.

To examine the relation between increasing IRIs programmed by the PI schedule and target behavior response rates (i.e., resp/min), Figure 2 shows correlation coefficients for each subject in successive blocks of four sessions across Phase 3. Following Ho et al. (2018), all instances of zero response rates were excluded from the analyses. There was no evidence of a positive relation between target response rates and IRI, and indeed, any significant relations observed were negative. Thus, the rate of target responding did not consistently depend upon the duration of the increasing IRIs arranged by the PI schedule, and if anything, response rates tended to decrease during the longer alternative IRIs.

Figure 2.

Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient in four-session blocks during Phase 3 (PI Thinning) in Experiment 1. Data points correspond to correlations between target response rates (resp/min) and alternative IRI length (s) over four-session blocks of PI thinning. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant correlation coefficient with the criterion of α = .05.

In order to better characterize resurgence within the first session of exposure to alternative reinforcement thinning with the PI schedule, Figure 3 shows cumulative records of target responding in the last session of Phase 2 (i.e., FI 10 s) and the first session of Phase 3 (i.e., PI schedule). The solid line represents the final Phase 2 FI 10-s session. The dotted line with superimposed points represents the first session of exposure to the PI schedule in Phase 3. The points on the dotted line represent the time at which an alternative reinforcer was delivered by the PI schedule. The insets in each panel provide a closer look at when resurgence began to occur. The programmed alternative IRI associated with resurgence was identified by finding the point at which the slopes of the functions for the last session of Phase 2 and the first session of Phase 3 obviously diverged visually and did not show a subsequent reversal. These points are indicated in each inset panel by the arrows and have the value of x (i.e., session time) and the associated IRI during which resurgence began to occur. Although there was some variability across rats in the time and the IRI during which they began to show resurgence, once target responding did increase during the first session of exposure to the PI schedule, response rates for all rats remained relatively constant or decelerated somewhat across the rest of the session. Thus, rather than target responding generally being more likely with longer IRIs during within-session alternative reinforcement thinning, it appears that target responding increases in rate at some point in the progression of increasing IRIs and then continues relatively steadily or decreases somewhat across additional increases in the IRI later in the session. This conclusion is consistent with the lack of correlation or negative correlation between target response rates and IRI presented in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Cumulative target responding as a function of session time in the last session of Phase 2 (FI 10 DRA) and the first session of Phase 3 (PI thinning) in Experiment 1. The solid and dotted lines represent the last session of Phase 2 and the first session of Phase 3, respectively. The dotted line represents the first session of Phase 3. The symbols on the dotted lines represent the time at which a reinforcer was delivered on the PI schedule in Phase 3. The insets in each panel show this same data but with zoomed-in axes. The arrows indicate the time at which resurgence began to occur based on visual inspection with text noting the session time (i.e., value of x) and the programmed alternative IRI at that time.

To examine whether repeated exposure to the PI schedule across sessions affected when resurgence began during the PI progression, Figure 4 shows the programmed IRI during which target responding increased during the first six sessions of PI thinning for each rat. The first six sessions are shown because, as noted with Figure 1 above, target response rates decreased across sessions of exposure to the PI schedule. Session seven was identified as the first session in which target response rates had reduced to the point of no longer being significantly elevated relative to the last session of exposure to the FI 10-s DRA in the previous phase as evaluated by paired samples t-tests. For Figure 4, the IRI during which resurgence began was identified as detailed in the description of Figure 3 above. Although there was a tendency for some rats to show resurgence later in the first session of exposure to the PI schedule than in subsequent sessions, there was no consistent change in the IRI during which resurgence began across sessions. Thus, repeated exposure to within-session alternative reinforcement schedule thinning had little consistent effect on when resurgence appeared as IRIs increased. As a result, the consistent decrease in session-wide response rates across sessions of exposure to the PI schedule during Phase 3 observed in Figure 1 likely did not result from changes in the IRI at which target responding started to increase.

Figure 4.

Programmed alternative IRI during which resurgence began to occur within-session across the first six sessions of exposure to the Phase 3 PI thinning condition in Experiment 1. Details of how IRIs were identified can be found in the text.

Discussion

Following suppression with a high rate of alternative reinforcement on an FI 10-s schedule, a transition to a within-session PI schedule generated robust and reliable resurgence of target responding in terms of session-wide response rates. Target response rates decreased across repeated sessions of exposure to the within-session PI schedule, although they remained elevated for a number of sessions relative to the previous phase. Examination of correlations between target response rates and IRIs for alternative reinforcement arranged by the PI schedule suggested that responding was not positively related to the duration of those IRIs, and if anything, was negatively related. Examination of within-session patterns of responding via cumulative records of target responding suggested that resurgence occurred at some IRI and then remained relatively steady or decreased somewhat across subsequent IRIs. Across repeated sessions of exposure to the PI schedule, the IRI at which resurgence occurred appeared not to change systematically. Finally, when alternative reinforcement was completely removed in Phase 4, there was little evidence of a further increase in target responding.

The finding that little additional resurgence occurred in Phase 4 following repeated within-session thinning of alternative reinforcement with the PI schedule is consistent with previous experiments on alternative reinforcement thinning (e.g., Schepers & Bouton, 2015; Sweeney & Shahan, 2013; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012). However, other studies have also found that removal of relatively low rates (i.e., 60/hr) of previously constant alternative reinforcement generates little resurgence (Craig & Shahan, 2016). The obtained overall rate of alternative reinforcement associated with the PI schedule in Phase 3 of the present experiment was approximately 34 per hr. Thus, it is unclear if the lack of resurgence with the final removal of alternative reinforcement was due to exposure to repeated within-session thinning per se or due to the relatively low session-wide rate of alternative reinforcement provided by the PI schedule across sessions. Experiment 2 addressed this question by comparing a PI group to a group that experienced an immediate transition to an FI schedule arranging the same session-wide reinforcement rate. In addition, the groups in Experiment 2 provided the opportunity to compare resurgence within sessions with a transition to either gradual (i.e., PI) or abrupt (i.e., FI) increases in IRIs for the alternative reinforcer.

EXPERIMENT 2

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

Ten experimentally naïve male Long-Evans rats (Charles River, Portage MI) were used in the experiment. Rats were 71–90 days old upon arrival and were maintained under the same conditions as described in Experiment 1. Ten modular Med Associates (St. Albans, VT) operant chambers identical to those described in Experiment 1 were used.

Procedure

All rats experienced training, Phase 1 (i.e., 30 sessions of VI 30-s for the target behavior), and Phase 2 (i.e., 15 sessions of target extinction and FI 10-s for the alternative behavior) as described in Experiment 1. Following the last session of Phase 2 rats were matched based on their target response rates and placed into one of two groups such that there was no statistical difference in target responding between them. One group was an exact replication of Experiment 1. For the other group, the alternative reinforcement schedule changed to an FI 105-s schedule in Phase 3 instead of the PI schedule. The FI 105-s schedule was calculated based on the overall programmed reinforcement rate during the PI phase in Experiment 1 so that while the distribution of reinforcers would be different across groups, the session-wide reinforcement rate would be similar. Phase 3 lasted for 16 sessions. Finally, both groups were exposed to five sessions of alternative response extinction in Phase 4.

Results

Figure 5 shows target response rates for both groups in the final three sessions of Phase 1, and target and alternative response rates in all subsequent phases of Experiment 2. Obtained reinforcement rates were similar across all phases of the experiment (see Table 2). Target responding during Phase 2 FI 10-s DRA declined at similar rates for both groups, and both acquired the alternative response. Independent samples t-tests conducted on response rates from the final session of Phase 2 revealed that neither target, t(8) = 0.82, p = .43, d = .53, nor alternative responding, t(5.49) = 0.82, p = .44, d = .53, differed statistically across groups. Upon introduction of the thinned alternative reinforcement schedule in Phase 3, both groups showed increases in target behavior. A 2 × 2 (Group x Phase) mixed-model ANOVA conducted on target response rates in the final session of Phase 2 and the first session of Phase 3 confirmed no effect of Group, F(1, 8) = 0, p = .99, ηp2 = 0, a significant effect of Phase, F(1, 8) = 26.03, p < .001, ηp2 = .76, and no significant Group x Phase interaction, F(1, 8) = 0.48, p = .5, ηp2 = .06. Thus, both groups showed resurgence and the session-wide magnitude of resurgence did not differ regardless of exposure to gradual or abrupt increases in the alternative IRI. A 2 × 16 (Group x Session) mixed-model ANOVA conducted on target response rates across all sessions of Phase 3 revealed a significant effect of Session, F(15, 120) = 20, p < .001, ηp2 = .71, but no significant effect of Group, F(1, 8) = 0.12, p = .74, ηp2 = .01, nor Group x Session interaction, F(15, 120) = 0.47, p = .95, ηp2 = .06. Therefore, regardless of group, repeated exposure to the thinned alternative reinforcement schedule reduced target responding across sessions of Phase 3. With the complete removal of alternative reinforcement in the transition from Phase 3 to Phase 4, there was no increase in session-wide target response rates for either group. A 2 × 2 (Group x Phase) mixed-model ANOVA conducted on target response rates in the final session of Phase 3 and the first session of Phase 4 confirmed no effect of Group, F(1, 8) = .26, p = .62, ηp2 = .03, nor Phase, F(1, 8) = 1.45, p = .26, ηp2 = .15, and no significant Group x Phase interaction, F(1, 8) = 3.44, p = .1, ηp2 = .30.

Figure 5.

Average target and alternative responding in all phases of Experiment 2. Closed circles represent the PI group, and open circles represent the FI Control group. Dotted and solid lines represent target and alternative responding, respectively. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

Summary of average (SEM) obtained SR rates from all phases of Experiment 2

| Last Session BL | Last Session Phase 2 | First Session Phase 3 | Last Session Phase 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 1.86 | (0.04) | 5.34 | (0.14) | 0.57 | - | 0.57 | - |

| FI Ctrl | 1.78 | (0.07) | 5.45 | (0.12) | 0.54 | (0.01) | 0.54 | (0.01) |

Note. All rates calculated as foods/min.

Figure 6 shows correlation coefficients for the relation between target response rates and obtained IRIs for each subject in the PI group in successive four-session blocks across Phase 3. In the first four-session block of PI thinning, only one of five rats showed a significant positive relation between target response rates and alternative IRIs. Beyond this exception, all rats show roughly the same pattern across Phase 3 in that the relation between target response rates and alternative IRI became successively more negative with repeated exposures to the within-session thinning arranged by the PI schedule. In the final eight sessions of PI thinning all five rats showed significantly negative relations between target response rate and alternative IRIs as they increased within-sessions.

Figure 6.

Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient in four-session blocks during Phase 3 (PI Thinning) for the PI group in Experiment 2. Data points correspond to correlations between target response rates (resp/min) and alternative IRI length (s) over four-session blocks of PI thinning. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant correlation coefficient with the criterion of α = .05.

Figure 7 shows within-session patterns of cumulative target responding as a function of session time in the last Phase 2 session of FI 10-s alternative reinforcement and the first session of Phase 3 alternative reinforcement thinning for both groups. As in Figure 2, the solid and dotted lines represent the final Phase 2 FI 10-s session and the first session of thinning, respectively. The points on the dotted line represent the time at which an alternative reinforcer was delivered according to either the PI or FI 105-s schedule. The IRI during which resurgence occurred within the session was determined for both groups as in Experiment 1. Because all programmed IRIs were the same for the FI group, we also determined the session time at which the identified IRI occurred in order to allow comparison between the two groups. These values are given in the insets in each panel of the figure. In general, the FI group began to show resurgence earlier in the session compared to the PI group. However, all rats regardless of group, showed approximately the same pattern of responding in that there was a point at which target response rates began to increase relative to the final Phase 2 session. After this point, target responding tended to decrease somewhat throughout the rest of the session (with the exception of TN16). Thus, it appears that such patterns of responding were not dependent on exposure to either the gradual (i.e., PI) or the abrupt (i.e., FI) thinning manipulation.

Figure 7.

Cumulative target responding as a function of session time in the last session of Phase 2 (FI 10 DRA) and the first session of Phase 3 (Thinning) in Experiment 2. The solid and dotted lines represent the last session of Phase 2 and the first session of Phase 3, respectively. The symbols on the dotted lines represent the time at which a reinforcer was delivered on the PI or FI 105-s schedule in Phase 3. Other details are as in Figure 3.

Figure 8 shows cumulative target responding as a function of cumulative reinforcer deliveries in the last Phase 2 session of FI 10-s alternative reinforcement and the first session of Phase 3 alternative reinforcement thinning for both groups. Note that to aid in assessment of when the increase in responding occurred, only the first 15 reinforcer deliveries are shown and some subjects have their data paths clipped at the y-axis limit. Cumulative target responding increased as a function of the number of alternative reinforcer deliveries obtained at the reduced rate for both groups, however, this increase appeared after substantially fewer reinforcers for the FI Control group. In the FI Control group, target response rates began to increase very quickly, occurring before the first reinforcer delivery at 105 s for three of five rats and after just one reinforcer for the remaining two rats. In contrast, in the PI group target response rates did not begin to meaningfully increase until after four to eight alternative reinforcer deliveries.

Figure 8.

Cumulative target responding as a function of cumulative alternative reinforcer deliveries in the last session of Phase 2 (FI 10 DRA) and the first session of Phase 3 (Thinning) in Experiment 2. The symbols on the dotted lines represent the time at which a reinforcer was delivered on the PI or FI 105-s schedule in Phase 3. Note that only the first 15 reinforcer deliveries are shown and some subjects have their data paths clipped at the y-axis limit.

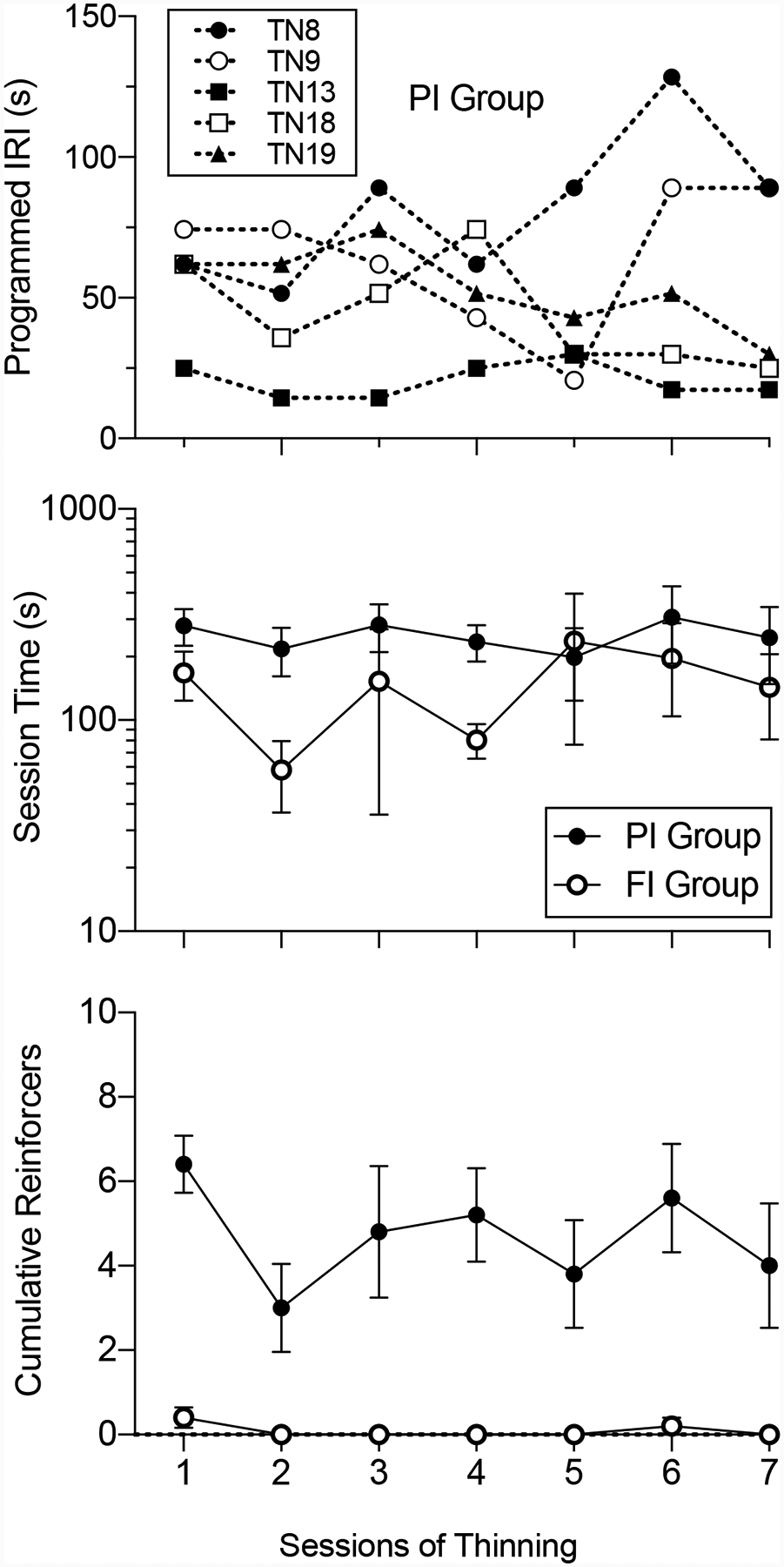

To determine if repeated exposures to the PI schedule of alternative reinforcement affected when resurgence began to occur across sessions, the top panel of Figure 9 shows the programmed IRI during which target responding increased for individual rats during the first seven sessions of exposure the PI schedule in Phase 3. The first seven sessions are included because the 8th session was identified as the first session in which target response rates for neither group differed statistically from the last session of exposure to the previous FI 10-s DRA phase as evaluated by paired samples t-tests. The IRIs in which target response rates began to increase were identified as in Figures 3 and 8. As in Experiment 1, repeated exposure to the PI schedule had no consistent effect on the IRI in which target responding started to increase.

Figure 9.

The onset of resurgence across the first seven Phase 3 thinning sessions in Experiment 2. The top panel shows the programmed alternative IRI during which resurgence began for individual rats in the PI group. The middle panel shows the mean session time at which resurgence began for both groups (note the logarithmic y-axis). The bottom panel shows the mean cumulative number of reinforcers after which resurgence began for both groups.

The middle panel of Figure 9 shows the time in the session at which target responding began to increase for the two groups across sessions of exposure to the PI or FI schedule of alternative reinforcement. Target response rates for rats in the PI group tended to increase earlier in the session than for rats in the FI group, but the time at which responding began to increase did not change systematically across sessions for either group. These conclusions are supported by a 2 × 7 (group x session) mixed-model ANOVA conducted on log-transformed session times (session times spanned nearly two orders of magnitude across rats and groups) showing a significant main effect of group F(1,8) = 5.47. p = .047, ηp2 = .41, but no significant effect of session F(3.3, 26.5) = 1.01, p = .41, ηp2 = .11, nor a group x session interaction F(6, 48) = 0.75, p =.61, ηp2 = .08.

The bottom panel of Figure 9 shows the number of reinforcers experienced before an increase in target responding for the two groups across sessions of exposure to the PI or FI schedule of alternative reinforcement. The number of reinforcers experienced before the increase in target responding increased was identified as described for Figure 9. Target response rates for rats in the FI group increased after experiencing fewer reinforcers than for rats in the PI group, but the point at which responding began to increase did not change systematically across sessions for either group. These conclusions are supported by a 2 × 7 (group x session) mixed-model ANOVA showing a significant main effect of group F(1,8) = 22.11, p = .002, ηp2 = .73, but no significant effect of session F(2.3, 18.6) = 2.42, p = .11, ηp2 = .23, nor a group x session interaction F(6, 48) = 1.59, p =.17, ηp2 = .16.

Discussion

The results of this experiment replicate those of Experiment 1 in showing that resurgence of target responding occurred during PI-schedule alternative reinforcement thinning. Likewise, resurgence also occurred with an abrupt transition to a similarly-reduced session-wide rate of alternative reinforcement arranged by a FI schedule. As in Experiment 1, the PI group showed no additional resurgence with a complete removal of alternative reinforcement, but neither did the FI group. Although the within-session reinforcer distribution was different for groups, the overall programmed rates were similar, and thus these data suggest that the absence of additional session-wide resurgence obtained following PI thinning in both experiments was likely a function of the relatively low rate of alternative reinforcement associated with the PI schedule (e.g., see also Craig & Shahan, 2016).

In terms of within-session responding, although rats in the FI control group generally showed resurgence earlier during exposure to the reduced reinforcement rate than rats that experienced the PI schedule, the overall patterns of target responding were similar across groups. Both groups showed that there was a point within the session at which target responding began to increase relative to responding during Phase 2, and once the increase occurred, rates of target responding were roughly constant or decreased across the rest of the session. For the PI group, this pattern of within-session responding generated mostly negative correlations between target response rates and the obtained increasing IRIs generated by the schedule later in the session. The experiment also showed that the point at which resurgence began to occur within the session during Phase 2 did not change systematically across sessions of exposure to the PI or FI schedule.

The finding that the PI group did not begin to respond to the target lever at higher rates until somewhat later in the session and after a larger number of alternative reinforcer deliveries suggests that it could be possible to further delay the onset of resurgence with more incremental changes to the alternative reinforcement schedule. The step-size for the PI schedule used here was 20%, but it could be potentially informative for future research to parametrically evaluate the differences in the onset of resurgence with different step-sizes during within-session PI alternative-reinforcement thinning.

General Discussion

In Experiment 1, following suppression of target responding with a high rate of alternative reinforcement, a transition to a within-session PI schedule of alternative reinforcement generated robust resurgence of target responding. Experiment 2 replicated this effect and showed that a switch to either a within-session PI schedule or an FI schedule arranging a similarly reduced session-wide alternative reinforcement produced similar levels of resurgence of target responding. In both experiments, following repeated exposures to the within-session PI schedule, no additional resurgence occurred with the subsequent complete removal of alternative reinforcement. But, Experiment 2 demonstrated that a group exposed to repeated sessions of a similarly reduced session-wide rate of alternative reinforcement on an FI schedule also showed no additional resurgence with a subsequent removal of alternative reinforcement. Thus, the lack of additional resurgence following repeated exposure to the PI schedule was likely due to the low overall rate of alternative reinforcement arranged by the PI schedule, rather than to the repeated exposure to within-session alternative reinforcement thinning per se.

Both experiments also showed that there was no consistent positive relation between target response rates and the length of alternative IRIs as they increased during the PI thinning sessions. Although previous experiments have reported positive correlations between the number of target responses and alternative IRI length (Ho et al., 2018; Lieving & Lattal, 2003), this outcome was likely an artifact of the longer sampling period inherent with longer IRIs. Examination of within-session patterns of responding in the present experiments suggest that responding emerged at some point in the session with both the PI and FI schedules, and then continued at a roughly constant or decelerated rate across the rest of the session.

Experiment 2 also showed that the gradually increasing IRIs arranged by a within-session PI schedule delayed the onset of resurgence in terms of both overall session time and total reinforcer deliveries as compared to a transition to an FI-schedule arranging the same session-wide alternative reinforcement rate. One possible explanation for the delayed within-session resurgence in the PI group relative to the FI group may be that the onset of resurgence is dependent on discriminating that reinforcement conditions have changed. For example, using a free-operant psychophysical procedure with pigeons, Bai et al. (2017) found that resurgence tended to occur sooner when alternative response extinction was signaled by a discrete stimulus, likely making the transition from the availability of alternative reinforcement to extinction more discriminable. In a similar vein, Context Theory (e.g., Bouton, 2019; Bouton & Todd, 2014; Bouton et al., 2012) suggests that resurgence is a form of ABC renewal in which the availability or unavailability of reinforcement defines a particular context. When there is a discriminable change in the context in which extinction of the target behavior occurred (e.g., a reduction in alternative reinforcement rate), resurgence is likely to occur. The difference in the onset of resurgence between the PI and FI groups in the present experiments seems to be consistent with such an interpretation. Because the increases in alternative IRIs on the PI schedule were unsignaled and incremental, it likely took the rats longer to discriminate that reinforcement conditions were changing as compared to the more dramatic change from an FI 10s to an FI 105s.

Although Context Theory provides a narrative to conceptualize the potential role of discrimination of changes in alternative reinforcement rate in resurgence, it does not provide a means to formalize such processes. To begin to formalize such processes, Shahan et al. (2020) recently suggested a theoretical account of resurgence (i.e., Resurgence as Choice in Context; RaC2) that integrates aspects of Context Theory into a broader, choice-based quantitative model of resurgence. In brief, RaC2 suggests that the allocation of responding to the target and alternative behaviors is governed by the longer-term relative values of behavior options across sessions. In the theory, the relative values of the two options are calculated based on the history of previously experienced reinforcement rates weighted by their relative recency. In addition, inspired by Context Theory, the model also includes a role for local discriminations of the relevant conditions of reinforcement for target and alternative behaviors based on the signaling effects of reinforcer deliveries or their absence. Although a detailed quantitative description of RaC2 can be found elsewhere (Shahan et al., 2020), both the impact of experienced reinforcement rates on relative values and the signaling effects of reinforcer deliveries imply that organisms must be sensitive to the distribution of reinforcers in time. But, as currently constructed the model only accounts for performance at a session-wide level, and thus it is not yet applicable to the within-session changes in alternative reinforcement examined here. Nevertheless, the present data appear to be compatible with the basic conceptual foundations of the theory in that, when the relative value for the alternative response began to decrease, target responding showed a relative increase in rate (i.e., resurgence). Additional detailed analyses examining how within-session transitions between a range of alternative reinforcement rates impact target responding would be helpful in extending the theory to smaller timescales.

The present data and those from other related experiments (e.g., Bai et al., 2017; Ho et al., 2018; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012) also seem to suggest the potential utility of future research directed at the role of timing processes in resurgence. Others have proposed that timing plays a critical role in choice by permitting the discrimination of reinforcement rates and changes in those rates (e.g., Gallistel, 2005; Gallistel & Gibbon, 2000; Gallistel et al., 2001). For example, Gallistel et al. (2001) showed that rats are able to quickly discriminate changes in reinforcement rates based on a small sample of IRIs, and that such discriminations appear to govern the reallocation of behavior in situations characterized by frequently changing relative reinforcement rates. Like all resurgence procedures, the present procedure provided the rats with a choice between two options for which the reinforcement conditions changed across time. Future research might usefully parametrically evaluate within-session resurgence following treatment with different alternative reinforcement rates and transitions to different PI step sizes and equivalent FI schedules. Such research could provide the data needed to better understand the potential role of timing and rate-change detection mechanisms in resurgence and might provide a more mechanistic grounding for the relative valuation and reinforcement discrimination processes suggested by RaC2.

Finally, further additional fine-grained examinations of resurgence during alternative reinforcement thinning might contribute to improved interventions for problem behavior in clinical settings. As noted above, Briggs et al. (2018) showed that resurgence of destructive behavior occurred for 19 of 25 (76%) cases at some point during schedule thinning, a finding that is consistent with the present experiment and previous reinforcement thinning experiments with animals (e.g., Schepers & Bouton, 2015; Sweeney & Shahan, 2013; Winterbauer & Bouton, 2012). The present data suggest that within-session thinning of alternative reinforcement with a PI schedule did not prevent resurgence during schedule thinning, but it did delay the occurrence of resurgence compared to an abrupt decrease in alternative reinforcement. A better understanding of the precise role of timing and detection of reinforcement-rate changes (i.e., schedule discriminability) in such effects could suggest ways to leverage these processes to better predict and control when resurgence occurs during and after clinical interventions. Although it is possible that resurgence might be an unavoidable side effect of such interventions in many circumstances, the ability to predict and control when it occurs could nevertheless provide a powerful tool for clinicians and caretakers alike.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant R01HD093734 (TAS) from the Eunice K. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors thank Kaitlyn Browning, Paul Cunningham, Rafaela Fontes, and Rusty Nall for helping to conduct the experiment.

References

- Bai JYH, Cowie S, & Podlesnik CA (2017). Quantitative analysis of local-level resurgence. Learning & Behavior, 45(1), 76–88. 10.3758/s13420-016-0242-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME (2019). Extinction of instrumental (operant) learning: interference, context, and contextual control. Psychopharmacology, 236(1), 7–19. 10.1007/s00213-018-5076-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, & Todd TP (2014). A fundamental role for context in instrumental learning and extinction. Behavioural Processes, 104, 13–19. 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Winterbauer NE, & Todd TP (2012). Relapse processes after the extinction of instrumental learning: Renewal, resurgence, and reacquisition. Behavioural Processes, 90, 130–141. 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Fisher WW, Greer BD, & Kimball RT (2018). Prevalence of resurgence of destructive behavior when thinning reinforcement schedules during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(3), 620–633. 10.1002/jaba.472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr EG, & Durand VM (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111–126. 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AR, Nall RW, Madden GJ, & Shahan TA (2016). Higher rate alternative non-drug reinforcement produces faster suppression of cocaine seeking but more resurgence when removed. Behavioural Brain Research, 306, 48–51. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AR, & Shahan TA (2016). Behavioral momentum theory fails to account for the effects of reinforcement rate on resurgence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 105(3), 375–392. 10.1002/jeab.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C, Cataldo M, Harrell R, Jefferson G, & Conner R (1993). Functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 23–36. 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleshler M, & Hoffman HS (1962). A progression for generating variable-interval schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 5(4), 529–530. 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman AM, Fisher WW, & Greer BD (2016). A preliminary investigation on improving functional communication training by mitigating resurgence of destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(4), 884–899. 10.1002/jaba.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR (2005). Deconstructing the law of effect. Games and Economic Behavior, 52, 410–423. 10.1016/j.geb.2004.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, & Gibbon J (2000). Time, rate, and conditioning. Psychological Review, 107(2), 289–344. 10.1037/0033-295x.107.2.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Mark TA, King AP, & Latham PE (2001). The rat approximates an ideal detector of changes in rates of reward: Implications for the law of effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 27(4), 354–372. 10.1037/0097-7403.27.4.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer BD, Shahan TA (2019). Resurgence as Choice: implications for promoting durable behavior change. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(3), 816–846. 10.1002/jaba.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Boelter EW, & Jarmolowicz DP (2011). Reinforcement-schedule thinning following functional communication training: Review and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 4, 4–16. 10.1007/bf03391770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Kuhn SAC, Long ES, & Rush KS (2005). Schedule thinning following communication training: Using competing stimuli to enhance tolerance to decrements in reinforcer density. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38(2), 177–193. 10.1901/jaba.2005.43-04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Toole LM, Long ES, Bowman LG, & Lieving GA (2004). A comparison of dense-to-lean and fixed lean schedules of alternative reinforcement and extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(3), 323–338. 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, & Thompson RH (2001). Reinforcement schedule thinning following treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(1), 17–38. 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, & Heil SH (2008). Contingency management in substance abuse treatment. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Ho T, Bai JYH, Keevy M, & Podlesnik CA (2018). Resurgence when challenging alternative behavior with progressive ratios in children and pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 110(3), 474–499. 10.1002/jeab.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KA, Cançado CR, Cook JE, Kincaid SL, Nighbor TD, & Oliver AC (2017). On defining resurgence. Behavioural Processes, 141, 85–91. 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KA, & St Peter Pipkin C (2009). Resurgence of previously reinforced responding: Research and application. The Behavior Analyst Today, 10(2), 254–266. 10.1037/h0100669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Rawson RA, & Mulick JA (1975). Extinction and reinforcement of alternative behavior. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 88(2), 640–652. 10.1037/h0076418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lieving GA, & Lattal KA (2003). Recency, repeatability, and reinforcer retrenchment: An experimental analysis of resurgence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 80(2), 217–233. 10.1901/jeab.2003.80-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsteller TM, & St. Peter CC (2012). Resurgence during treatment challenges. Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la Conducta, 38(1), 7–23. 10.5514/rmac.v41.i2.63775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parry-Cruwys DE, Neal CM, Ahearn WH, Wheeler EE, Premchander R, Loeb MB, & Dube WV (2011). Resistance to disruption in a classroom setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(2), 363–367. 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petscher ES, Rey C, & Bailey JS (2009). A review of empirical support for differential reinforcement of alternative behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(3), 409–425. 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard D, Hoerger M, Mace FC, Penney H, & Harris B (2014). Clinical translation of animal models of treatment relapse. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 101(3), 442–449. 10.1002/jeab.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roane HS, Fisher WW, Sgro GM, Falcomata TS, & Pabico RS (2004). An alternative method of thinning reinforcer delivery during differential reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 213–218. 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers ST, & Bouton ME (2015). Effects of reinforcer distribution during response elimination on resurgence of an instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition, 41(2), 179–192. 10.1037/xan0000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, Browning KO, & Nall RW (2020). Resurgence as Choice in Context: Treatment duration and on/off alternative reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113(1), 57–76. 10.1002/jeab.563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, & Craig AR (2017). Resurgence as Choice. Behavioural Processes, 141, 100–127. 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman KE, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, & Stitzer ML (1999). Voucher-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcement magnitude. Psychopharmacology, 146(2), 128–13 10.1007/s002130051098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BM, Smith GS, Shahan TA, Madden GJ, & Twohig MP (2017). Effects of differential rates of alternative reinforcement on resurgence of human behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 107(1), 191–202. 10.1002/jeab.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Peter CC (2015). Six reasons why applied behavior analysts should know about resurgence. Revista Mexicana de Análisis de la Conducta, 41, 252–268. 10.5514/rmac.v41.i2.63775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, & Shahan TA (2013). Effects of high, low, and thinning rates of alternative reinforcement on response elimination and resurgence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 100(1), 102–116. 10.1002/jeab.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiger JH, Hanley GP, & Bruzek J (2008). Functional communication training: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 16–23. 10.1007/BF03391716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venniro M, Caprioli D, Zhang M, Whitaker LR, Zhang S, Warren BL, … & Chiamulera C (2017). The anterior insular cortex→ central amygdala glutamatergic pathway is critical to relapse after contingency management. Neuron, 96(2), 414–427. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert VM, Lerman DC, Call NA, & Trosclair-Lasserre N (2009). An evaluation of resurgence during treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(1), 145–160. 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker DP, Harding JW, Berg WK, Lee JF, Schieltz KM, Padilla YC, … & Shahan TA (2011). An evaluation of persistence of treatment effects during long-term treatment of destructive behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 96(2), 261–282. 10.1901/jeab.2011.96-261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer NE, & Bouton ME (2010). Mechanisms of resurgence of an extinguished instrumental behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 36(3), 343–353. 10.1037/a0017365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer NE, & Bouton ME (2012). Effects of thinning the rate at which the alternative behavior is reinforced on resurgence of an extinguished instrumental response. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 38(3), 279–291. 10.1037/a0028853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]