Abstract

It has been demonstrated in a number of communities that the rates of serious crimes such as homicides and intimate partner violence have increased as a result of lockdowns due to COVID-19. To ascertain whether this is a universal trend the electronic autopsy files at Forensic Science South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, were searched for all homicides occurring between January 2015 and December 2020. There were 92 cases with 17 homicides in 2015 out of a total of 1356 cases (1.3%),18 in 2016 (18/1340 = 1.3%), 23 in 2017 (23/1419 = 1.6%); 14 in 2018 (14/1400 = 1.0%), 15 in 2019 (15/1492 = 1.0%) but in 2020 there were only 5 (5/1374 = 0.4%) (p < 0.02). Thus the incidence of homicides has fallen significantly in South Australia since the beginning of the pandemic. As the occurrence of serious crimes of violence and homicide has not followed a standard pattern in different communities it will be important to evaluate specific populations and subgroups rather than merely relying on accrued national data or extrapolating from one country to another. Pathologists, epidemiologists and health officials will need to specifically monitor local trends to understand more clearly what effects, if any, the pandemic has had on particular subgroups of deaths in order to more clearly understand causal relationships.

Keywords: COVID-19, Homicide, Intimate partner violence, Trends, Falling rates

Introduction

The pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) was first identified in December 2019 and has been responsible for considerable global morbidity and mortality associated with extreme economic disruptions. The novel coronavirus results in COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) which has had significant, deleterious and sometimes idiosyncratic effects on multiple organ systems of infected individuals [1]. In addition, fear of the disease, quarantining, and lockdown strategies restricting individuals to their homes, have had marked psychological effects on many populations [2].

It has also been proposed that the rates of serious crimes such as homicides and intimate partner violence have either remained unchanged or have increased as a result of lockdowns due to COVID-19 [3] as it is theorized that lockdowns enhance opportunities for violent crimes by bringing perpetrators closer to victims for longer periods of time. It has been suggested by the United Nations that the incidence of domestic violence increased by more than 30% in some countries following lockdown [4] a trend that has been referred to as a “hidden pandemic” [5]. The following study was, therefore, undertaken to determine whether the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated strategies are universal and if so, what effect they may have had on homicide rates in a regional Australian center.

Materials and methods

The electronic autopsy files at Forensic Science South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, were searched for all homicides occurring between January 2015 and December 2020. Forensic Science South Australia is the referral center for all homicides occurring in the state which has a population of approximately 1.6 million. All cases were the subject of full police investigations with complete autopsy examinations, including toxicology where possible. Individual cases were de-identified and age, sex and causes of death were tabulated, and the numbers of homicides per year were calculated. The results were analyzed using Fisher’s Exact test.

Results

A total of 92 cases were found consisting of 66 males and 26 females (M:F = 2.5:1) with an age range of 9 months to 88 years (average 40.7 years). There were 38 deaths due to blunt force trauma, 36 stabbings, 10 strangulations, 7 gunshot wounds, 3 miscellaneous and 2 undetermined (N = 96; there were four cases with more than one cause).

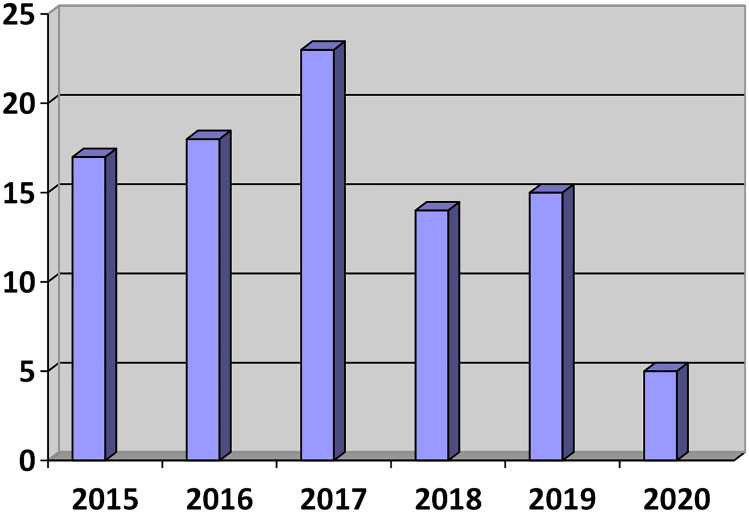

The numbers of homicides per year ranged from 5 to 23, with the total numbers of annual autopsies ranging from 1356 to 1492. Specifically in 2015 there were 17 homicides out of a total of 1356 cases (1.3%), in 2016 there were 18 (18/1340 = 1.3%), in 2017 there were 23 (23/1419 = 1.6%); in 2018 there were 14 (14/1400 = 1.0%), in 2019 there were 15 (15/1492 = 1.0%) but in 2020 there were only 5 cases (5/1374 = 0.4%) (p < 0.02). The annual numbers were too small to determine whether there had been any significant changes in methods, with blunt force trauma accounting for between 18 to 64% of cases annually overall, and stabbings 20 to 47% (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Annual numbers of homicides in South Australia, Australia from 2015 to 2020

Discussion

Following the significant negative economic effects and societal disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic there have been reported increases in the incidence and prevalence of suicide, mental illness and self harm [2]. Reasons for this include social isolation from lockdown or stay-at–home (quarantine) orders, job losses and unemployment [3]. Prolonged quarantine in particular has been associated with boredom, frustration and societal stigma, and issues with inadequate basic supplies. Suicide has been reported in previous outbreaks that necessitated quarantine [6] and a study of Chinese university students during a period of state-enforced quarantine in early 2020 found that 67% reported features of traumatic stress, 47% had depressive symptoms, 35% had anxiety and a full 20% expressed suicidal ideation [7]. However, despite apparent increases in suicides in certain countries such as Germany [8], countries such as Korea have had a fall in numbers of suicides, by 6.9% in the first eight months of 2020 [9]. Thus, lethal self-harm responses to stresses generated by the pandemic appear quite variable among communities.

In turning to assaults, while numbers of minor crimes committed by groups of young peers have decreased in the United States during the pandemic, more serious crimes such as intimate partner violence and homicide rates have increased in some jurisdictions. For example, a 15% increase in homicides from 2019 to 2020 has been documented in Philadelphia [3]. A study from Los Angeles, however, showed that although robbery and shop lifting had decreased during the pandemic that homicide, assault with a deadly weapon and intimate partner violence had shown no significant changes [10]. This plateauing of numbers occurred despite markedly increased numbers of firearm sales in the United States in 2020 [11].

In contrast, the current study has shown that there has been a significant decrease in homicides in South Australia during 2020 with a fall in the percentage of homicides from 1.0–1.6% (average 1.2%) in the preceding five years to 0.4% in 2020 (p < 0.02). The reasons for this remain unclear as South Australia has been relatively protected compared to other areas of the world such as the United States, India, Brazil and the United Kingdom, with only 606 total cases and 4 COVID-related deaths to date [12]. Despite the low numbers, however, South Australia has still had very effectively managed lockdowns, home quarantines, travel bans, border closures and closures of public places including bars and clubs, followed by periods where the number of patrons allowed inside venues was severely restricted. As homicide is often fueled by criminal activities, particularly related to illicit drugs, and alcohol consumption, it may be that the government-imposed COVID restrictions limited these type of interactions. Certainly the numbers of homicides in Mexico decreased from a national average of 81 to 54 per day after COVID restrictions were imposed and in Peru a fall in homicides involving female victims was also observed [13]. The failure to demonstrate any changes in the numbers of violent deaths in Greece may have been influenced by the short time period (one month) that was studied after lockdown [14].

A shortcoming of the present study is the low number of cases compared to other jurisdictions with much higher homicide rates. Despite this however, the decline in homicides locally after the pandemic was sufficiently pronounced to reach statistical significance. It appears that trends on both natural and unnatural deaths have changed during the COVID era, sometimes in an unpredictable manner. Thus the incidence of serious crimes of violence and homicide has not followed a standard pattern in different communities. Whether this is influenced by the favored method of assault is uncertain, however homicides due to firearms are far more common in the United States than in Australia [15], where blunt force trauma and stabbing predominate, as can be seen from the current data.

As has been noted in studying suicides [16] it is important to evaluate specific populations and subgroups rather than merely depending on accrued national data or extrapolating from one community to another. It will be important for pathologists, epidemiologists and public health officials to continue to monitor local trends to understand more clearly what effects, if any, the pandemic has had on specific subgroups of deaths in order to more clearly understand causal relationships.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Moretti M, Malhotra A, Visona SD, Finley SJ, Osculati AMM, Javan GT. The roles of medical examiners in the COVID-19 era: comparison between the United States and Italy. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12024-021-00358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr MJ, Steeg S, Webb RT, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care-recorded mental illness and self-harm episodes in the UK: population-based cohort study. Lancet Pub Health. 2021;6:e124–e135. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boman JH, Gallupe O. Has COVID-19 changed crime? Crime rates in the United States during the pandemic. Am J Crim Just. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09551-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 202;38:2753–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Xue J, Chen J, Chen C, Hu R, Zhu T. The hidden pandemic of family violence during COVID-19: unsupervised learning of tweets. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e24361. doi: 10.2196/24361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the literature. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun S, Goldberg SB, Lin D, Qiao S, Operario D. Psychiatric symptoms, risk, and protective factors among university students in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Glob Health. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buschmann C, Tsokos M. Corona-associated suicide – observations made in the autopsy room. Leg Med. 2020;46:101723. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim AM. The short term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on suicides in Korea. Psychiatr Res. 2021;295:113632. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campedelli GM, Aziani A, Favarin S. Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: an empirical analysis of the short-term aftermath in Los Angeles. Am J Crim Just. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09578-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khubchandani J, Price JH. Public perspectives on firearm sales in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inj Prevent. 2021;2:e12293. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of South Australia COVID-19 dashboard. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/infectious+diseases/covid-19/about+covid-19/latest+updates/covid-19+dashboard. Accessed 15 Feb 2021.

- 13.Calderon-Anyosa RJC, Kaufman JS. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Prevent Med. 2021;143:106331. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakelliadis EI, Katsos KD, Zouzia EI, Spiliopoulou CA, Tsiodras S. Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on characteristics of autopsy cases in Greece. Comparison between 2019 and 2020. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;313:110365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Byard RW, Haas E, Marshall DT, Gilbert JD, Krous HF. Characteristic features of pediatric firearm fatalities – comparisons between Australia and the United States. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54:1093–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin A, van den Heuvel C, Byard RW. Differences in local and national database recordings of deaths from suicide. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2017;13:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s12024-017-9853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]