Abstract

Objective

Describe trends and patterns in long-term opioid prescriptions among adults with musculoskeletal conditions (MSK).

Design

Interrupted time-series analysis based on an open cohort study.

Setting

A representative sample of 402 Australian general practices contributing data to the MedicineInsight database.

Participants

811 174 patients aged 18+ years with an MSK diagnosis and three or more consultations in any two consecutive years between 2012 and 2018. Males represented 44.5% of the sample, 28.4% were 65+ years and 1.9% were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Annual prevalence and cumulative incidence (%) of long-term opioid prescribing (3+ prescriptions in 90 days) among patients with an MSK. Average duration of these episodes in each year between 2012 and 2018.

Results

The prevalence of long-term opioid prescribing increased from 5.5% (95% CI 5.2 to 5.8) in 2012 to 9.1% (95% CI 8.8 to 9.7) in 2018 (annual change OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.09), but a slightly lower incidence was observed in 2018 (3.0% vs 3.6%–3.8% in other years; annual change OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98 to 0.99). The incidence was between 37% and 52% higher among practices located in rural Australia or lower socioeconomic areas. Individual risk factors included increasing age (3.4 times higher among those aged 80+ years than the 18–34 years group in 2012, increasing to 4.8 times higher in 2018), identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (1.7–1.9 higher incidence than their peers), or living in disadvantaged areas (36%–57% more likely than among those living in wealthiest areas). Long-term opioid prescriptions lasted in average 287–301 days between 2012 and 2016, reducing to 229 days in 2017 and 140 days in 2018. A longer duration was observed in practices from more disadvantaged areas and females in all years, except in 2018.

Conclusions

The continued rise in the prevalence of long-term opioid prescribing is of concern, despite a recent reduction in the incidence and duration of opioid management.

Keywords: musculoskeletal disorders, pain management, epidemiology, back pain, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A national sample including 135 358 instances of long-term opioid prescriptions (3+ opioid prescriptions in 90 days) and 811 174 adult patients with musculoskeletal conditions from Australian general practice over 7 years.

Patients and practices from all Australian states, with different socioeconomic and demographic profiles, and from urban and rural regions are included in the study.

The study explores the incidence and duration of long-term opioid prescriptions over time and their association with sociodemographic characteristics.

Individuals attending multiple clinics for prescriptions are not tracked by MedicineInsight, which may underestimate the real frequency.

Moreover, the findings reflect prescribing patterns rather than medication use, and the available data do not allow the investigation of the place/professional that initiated these prescriptions.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal conditions (MSK) represent a public health problem worldwide due to their substantial impact on the quality of life, increasing prevalence and contribution to the global burden of disability.1 2 In Australia, MSK affect approximately 30% of adults (6.1 million individuals), but its prevalence is even higher in lower socioeconomic groups and the elderly.3–5 In terms of health costs, MSK accounted for $A5690 million in 2008–09, representing 9% of the total Australian healthcare expenditure in that year and the fourth most expensive group of diseases in the country.6 MSK are among the 10 most frequent problems managed by general practitioners (GPs).4 The principal symptom associated with these visits is chronic pain.1 3 5–7

Countries such as Australia, the USA, Canada, Belgium and the UK recognise MSK and chronic pain management as a public health priority and have developed national policies aiming to improve prevention and management.1 8 The strategies and actions include models of care orientated towards high-value care options for MSK pain management, as well as regular monitoring of their prevalence, patterns of medication use/prescription and side effects related to the use of these medications.1 2 8 Current guidelines recommend non-pharmacological interventions as the primary initial approach for managing MSK pain. Simultaneously, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs represent the first-line pharmacological therapy.8–10 The use of opioids for pain management is discouraged due to the increased risk of severe side effects, especially in elderly patients or among long-term users.8–15 Harmful effects associated with opioid use include sedation, falls, respiratory depression and death, as well as an increased risk of dependence and diversion. Moreover, long-term use of opioids can potentiate chronic pain mechanisms, reducing the effect of these drugs at standard doses.8 9 14

Despite their recognised harmful effects, opioid use has increased in the last decades, especially among high-income countries such as the USA, Canada, the UK, Germany, Norway, Australia and New Zealand.16–20 In the USA, for example, the use of opioids (licit and illicit) escalated 10–14 times in the last two decades, while in Australia there was a 238% increase in the number of people receiving potent opioids between 2006 and 2015.19 20 However, some countries have reported an apparent plateau of opioid use among patients with MSK in recent years.15 21–26 In Australia, a systematic review showed a significant rise in opioid use up to 2017, mainly driven by oxycodone.27 Nonetheless, most data regarding opioid use in Australia analysed data from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) database.27 PBS data represent an efficient and cost-effective way to monitor dispensed medicines and trends over time.28 However, studies based on dispensed medications tend to underestimate opioid use,29 the investigation of patterns is usually restricted to age and sex distribution and the use of aggregated data cannot distinguish between incident users, prevalent users or long-term users.27 Understanding the determinants and patterns of long-term opioid prescription/use is fundamental to inform stakeholders and propose targeted interventions aiming to reduce their use for MSK management.11–13 18 27 In Australia, only a few studies have examined opioid prescribing and its association with sociodemographic characteristics at the local level but not across states or including urban and rural areas.30 31

In this sense, MedicineInsight is a national longitudinal database established in 2011 by NPS MedicineWise to collect comprehensive, de-identified patient data from GP electronic medical records (EMR) across Australia.32 Data from MedicineInsight have been previously used to assess trends and patterns of preventive activities, medication prescriptions and laboratory requests for acute and chronic conditions managed in Australian general practice.5 32–37 This study aims to use MedicineInsight data to estimate the prevalence and cumulative incidence of long-term opioid prescriptions among adult patients with MSK. Furthermore, it describes trends in opioid prescriptions between 2012 and 2018 and investigates associations with patient and practice characteristics.

Methods

Study design

This is an interrupted time-series study analysing data from MedicineInsight, a large general practice database including patients from 662 general practices (8.2% of all general practices in Australia) and over 2700 GPs across Australia.32 Although practices participating in MedicineInsight were recruited using a non-random process, all Australian states and regions are represented, and the database includes practices that vary in size and type of services offered. Patients in the database have been found to be comparable with the general population as measured by sociodemographic variables and clinical conditions.5 32 The information extracted from MedicineInsight for the present study include EMR dating between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2018.

Patients within a practice have a unique identifying number which allows all the EMR held in the database for an individual to be linked and tracked over time. Patients’ EMR are collected monthly, de-identified and securely transferred to NPS MedicineWise’s data warehouse. Routinely collected information includes: demographics (gender, aboriginality, year of birth, patient postcode and area of residence), clinical information (diagnoses, reasons for consultation, immunisations), prescribed medications (generic and brand names, doses, active ingredient and number of repeats reasons for prescription, known allergies, drug reactions), pathology test results, clinical measurements (temperature, blood pressure, weight, height, waist circumference) and smoking status.32

Participants

To improve data quality, only practices established for at least 2 years before the end of the analysis period, with recorded data (ie, diagnosis, reason for encounter or reason for prescription) in at least 10% of clinical encounters, an average of 30 or more prescriptions per week and a consistent number of consultations over time (ie, ratio between the highest and lowest number of annual total consultations lower than five, no gaps of >6 weeks in the previous 2 years in practice data) were included.

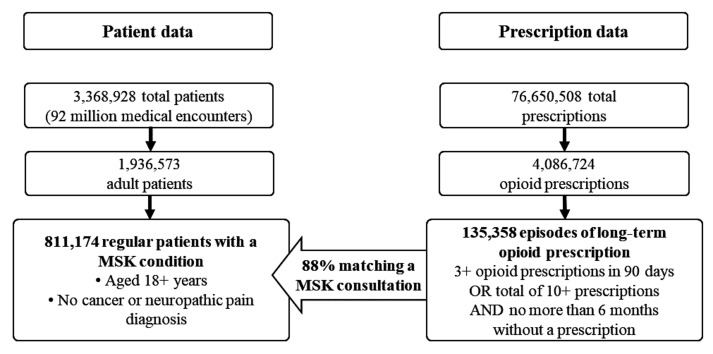

The sample included all regular patients (ie, individuals with three or more consultations in any two consecutive years) aged 18 years or older (figure 1). The sample was further restricted to patients with at least one recorded visit in the 12 months preceding the initial opioid prescription and follow-up time ended 6 months after the last medical encounter, in order to differentiate between past and current patients on opioids.21 Therefore, despite data in MedicineInsight were available since 2011, the analyses were restricted to the period 2012–2018. Patients were also excluded if they had a record of cancer or neuropathic pain up to 12 months before or 6 months after the start date of the initial long-term opioid prescription episode. Therefore, we used data from 811 174 regular adult patients with MSK attending 402 general practices across Australia.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of data extraction from MedicineInsight database for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions (MSK) and opioid prescriptions. Period 2012–2018.

Musculoskeletal conditions

Data regarding MSK conditions were extracted from the database using previously published algorithms.5 The diagnosis, reason for encounter and reason for prescription fields were used to identify patients with a potentially painful MSK condition, as these are typical fields used by GPs to record morbidity in Australian general practice.32 Most general practices use coding systems (ie, ‘Docle’, ‘Pyefinch’ or the International Classification of Primary Care 2), and these were mapped to the Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms.5 32 38 The list of MSK conditions included: (i) osteoarthritis, (ii) osteoarthrosis, (iii) spondylarthritis, (iv) fibromyalgia, (v) polymyalgia rheumatica, (vi) rheumatoid arthritis, (vii) myofascial pain, (viii) chronic fatigue syndrome, (ix) gout, (x) Paget disease, (xi) osteoporosis, (xii) tenosynovitis, (xiii) chronic back pain and (xiv) other conditions recorded as ‘chronic musculoskeletal pain’. Synonyms and misspellings of these terms were also used, considering that GPs can also use free-text in the completion of the diagnosis. The data extraction algorithms used in this study are available from the authors by request.

Prescription data

Data regarding opioid prescriptions (ie, codeine, tramadol, tapentadol, oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, hydromorphone) were extracted from the prescription dataset using generic and brand names.39 Using recommendations from the literature,21 40 a new ‘episode of opioid prescription’ was defined as a prescription provided to the patient where no opioid was prescribed within 6 months from the ‘end of the last episode’. The ‘end date’ of an ‘episode of opioid prescription’ was considered as being 28 days after the last prescription was provided (ie, in Australia, opioids can be prescribed for up to 28 days without repeats).8 39 An episode of ‘long-term opioid prescription’ was defined as patients receiving (i) three or more scripts (including the initiating script) within 90 days of the initial script or (ii) a total of 10 or more consecutive scripts with an interval lower than 180 between ‘episodes of opioid prescription’, even though the first three were not provided within 90 days. An episode of ‘long-term opioid prescription’ ended when the patient had not received a prescription for opioids for 6 or more months.8 39 A total of 135 358 instances of long-term opioid prescriptions were identified over the period (figure 1), with 88% of them matching a consultation when the GP recorded an MSK as the reason for diagnosis, reason for encounter and/or reason for prescription (ie, excluding cancer or neuropathic pain) within a period lasting from 30 days before the initial opioid prescription, or up to 120 days after it.8 39

Data analysis

The prevalence of long-term opioid prescriptions was estimated as the percentage of regular patients with MSK attending the practice that year that were on opioids (ie, long-term opioid prescription), either because these prescriptions started in that year or previous years. The cumulative incidence of long-term opioid prescription was estimated as the percentage of regular patients with MSK in any year between 2012 and 2018 starting opioids that year (ie, patients ‘at risk’ not on opioids). The average annual change in the prevalence or incidence of long-term opioid prescription was investigated using logistic regression, and the results expressed as ORs with their respective 95% CIs.

The association between sociodemographic characteristics and the incidence of long-term opioid prescription was also explored using logistic regression, and the variables were included in the models considering two hierarchical levels. The first level included practice characteristics: state, rurality (ie, major cities, inner regional or outer regional/remote Australia) and the practice’s Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD, as provided by MedicineInsight (based on the postcode of the practice) and divided in quintiles). IRSAD is a relative indicator of economic and social advantage/disadvantage of people and households within an area generated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and based on a range of census variables.41 Higher IRSAD scores indicate that the practice is located in a more advantaged area. The second level included patient characteristics: gender (males/females), age in groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–79, 80+ years), aboriginality (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander: no, yes, not recorded) and the patient’s IRSAD (divided in quintiles).

Results of the logistic regression models were expressed as marginal predicted probabilities (ie, adjusted cumulative incidence) instead of OR to facilitate interpretation of the results, as many medical doctors, researchers and health policymakers are not familiar with these measures of association.42 Wald tests for heterogeneity or trend were used to estimate the p values due to the use of clustered data (ie, practice defined as the cluster).

Quantile regression models were used to investigate the variables associated with the median duration (in days) of the long-term opioid prescription among incident cases, considering the same levels of adjustment as above.

All analyses were performed using the statistical software STATA V.15.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA) and conditioned to the patient’s probability of being in the sample to minimise selection bias (ie, the likelihood of receiving medical treatments or diagnosis increase with the number of visits to the practice).43

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not directly involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research. However, the provision of information for the study underwent a formal approval process guided by the MedicineInsight independent external Data Governance Committee that includes GPs, consumer advocates, privacy experts and researchers. Moreover, two of the authors are active GPs regularly attending patients affected by MSK, which also supported the design of the study.

Results

MedicineInsight included a total sample of 3 368 928 total patients, with 1 936 573 of them aged 18 years or older (figure 1). Most practices were from New South Wales (35.5%) and Victoria (21.7%) and located in major cities (60.5%), but practices from all regions and with a different socioeconomic profile were included (online supplemental table 1). Males represented 42.2% of the adults in the database, while 28.7% were 65 years or older and 2.0% Aboriginals or Torres Strait Islanders. The most common MSK among patients aged 18+ years were chronic back pain (16.6%), osteoarthritis (13.7%), tenosynovitis (6.7%) osteoporosis (4.2) and gout (4.0%). The rest of the conditions showed a prevalence lower than 1%.

bmjopen-2020-045418supp001.pdf (82KB, pdf)

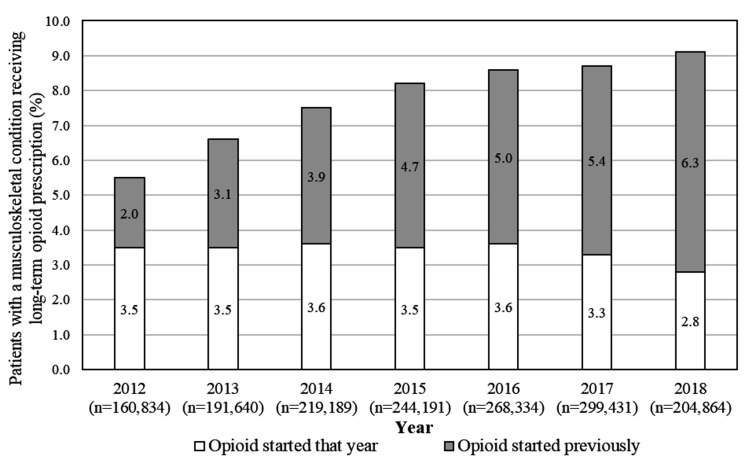

The analysed sample of unique regular adult patients with MSK attending one of the MedicineInsight practices between 2012 and 2018 consisted of 811 174 individuals. As shown in figure 2, the number of these patients per year ranged between 160 834 and 299 431 individuals.

Figure 2.

Frequency of long-term opioid prescription for the management of musculoskeletal conditions. Period 2012–2018. Number in parentheses (n) represent the total number of regular patients with a musculoskeletal condition in that year from a total of 811 174 regular patients investigated over the whole period.

The overall ‘prevalence’ of long-term opioid prescribing (ie, patients with MSK on opioids, either because they started that year or in previous years) increased from 5.5% (95% CI 5.2 to 5.8) in 2012 to 9.1% (95% CI 8.8 to 9.7) in 2018 (annual change OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.09; p value for trend <0.001). Figure 2 shows the increase was related to a higher proportion of patients starting opioids in previous years, rather than a rise in incident cases (ie, those who started opioids in that year).

The MSK with the highest rate of long-term opioid prescribing were spondyloarthritis (13.8%) and fibromyalgia (13.3%) in 2012, and Paget disease (22.2%) and fibromyalgia (21.4%) in 2018 (online supplemental figure 1). Patients with fatigue syndrome or gout were less likely to be on long-term opioids (4.4% and 3.4% in 2012; 8.6% and 6.9% in 2018, respectively).

bmjopen-2020-045418supp002.pdf (721.8KB, pdf)

Table 1 shows males represented 44.5% of the sample, 28.4% were 65+ years and 1.9% were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders. Individuals from different socioeconomic settings were all represented in the study, and 40.0% were for regional or remote areas. The cumulative incidence of long-term opioid prescription (ie, excluding those who were already on opioids) among regular patients with an MSK ranged between 3.6% and 3.8% between 2012 and 2016, dropping to 3.0% in 2018 (3.0%; annual change OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.98 to 0.99; p value for trend 0.002).

Table 1.

Cumulative incidence of long-term opioid prescription for the management of musculoskeletal conditions according to practice and patient’s characteristics (regular patients* aged 18+ years, Australia, 2012–2018)

| Year | Long-term opioids—incidence (%) | |||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| Regular patients with MSK ‘at risk’* | 157 528 | 185 358 | 210 089 | 231 961 | 253 648 | 281 655 | 190 079 | |

| Overall incidence—% (95% CI) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.0) | 3.7 (3.5 to 3.9) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.0) | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.1) | |

| Practice characteristics† | %‡ | |||||||

| State | ||||||||

| NSW | 36.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| VIC | 21.5 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.1 |

| QLD | 14.3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| WA | 11.3 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.5 |

| TAS | 10.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| SA | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 2.9 |

| ACT | 2.7 | 6.0 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 3.3 |

| NT | 0.6 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Rurality | ||||||||

| Major cities | 60.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Inner regional | 26.7 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 |

| Outer regional/Remote | 13.3 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.7 |

| IRSAD quintile | ||||||||

| Very high | 25.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

| High | 16.7 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| Middle | 22.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.1 |

| Low | 15.6 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.0 |

| Very low | 19.1 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.3 |

| Patient’s characteristics§ | ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 44.5 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| Female | 55.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 18.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| 35–49 | 23.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 |

| 50–64 | 28.8 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| 65–79 | 21.9 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| 80+ | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 6.2 |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | ||||||||

| No | 77.9 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 |

| Yes | 1.9 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 5.3 |

| Not recorded | 20.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.7 |

| IRSAD quintile | ||||||||

| Very high | 23.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| High | 16.9 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 2.7 |

| Middle | 23.0 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.0 |

| Low | 17.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.2 |

| Very low | 18.7 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

*At least three consultations in any two consecutive years from 2012 to 2018. Numbers (n) represent the number of regular patients with a musculoskeletal condition in that year, excluding those who were already on opioids (ie, patients ‘at risk’).

†Logistic regression models with all practice characteristics mutually adjusted. Values in ‘bold’ represent those associations with a p value <0.01.

‡Values in italics represent the total sample distribution (ie, regular adult patients with MSK) a musculoskeletal condition) according to these characteristics.

§Logistic regression models with all patient characteristics mutually adjusted+adjustment for practice characteristics. Values in ‘bold’ represent those associations with a p value <0.01.

¶Values in parentheses represent the 95% CI of the incidence.

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; IRSAD, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage; MSK, musculoskeletal condition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

The same table also shows the sociodemographic factors associated with the cumulative incidence of long-term opioid prescribing. In any investigated year, the cumulative incidence was 37%–52% higher among individuals attending practices located in rural Australia or areas with a very low IRSAD, compared with those attending practices located in major cities or areas with a higher IRSAD. Individual risk factors associated with a higher incidence of long-term opioid prescribing included increasing age (3.4 times higher among those aged 80+ years than the 18–34 years group in 2012, increasing to 4.8% in 2018), identifying as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (1.7–1.9 higher incidence than their peers), or living in areas with a lower IRSAD (36%–57% more likely than among those living in wealthiest areas). Neither the state where the practice was located nor the patient’s gender was associated with this outcome.

The average duration of the long-term opioid prescriptions among incident cases ranged from 287 to 301 days between 2012 and 2016, reducing to 229 days in 2017 and 140 days in 2018 (table 2). The most consistent pattern observed over the investigated years was an increased duration of prescribing among individuals attending practices located in lower socioeconomic areas (ie, up to 152 days longer than those attending practices located in the wealthiest areas) or females (ie, up to 77 days longer than in males). However, these differences were not evident in 2018.

Table 2.

Average time on long-term opioid prescription for the management of musculoskeletal conditions among incident cases according to practice and patient’s characteristics (regular patients* aged 18+ years. Australia, 2012–2018)

| Time on long-term opioids among incident cases (days) | |||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Incident cases | 5621 | 6647 | 7944 | 8652 | 9572 | 9958 | 5672 |

| Median duration (95% CI)† | 287 (266 to 308) |

301 (281 to 321) |

295 (279 to 311) |

288 (272 to 304) |

294 (281 to 307) |

229 (221 to 237) |

140 (135 to 145) |

| Practice characteristics‡ | |||||||

| State | |||||||

| NSW | 266 | 299 | 308 | 273 | 292 | 210 | 134 |

| VIC | 283 | 309 | 312 | 313 | 268 | 230 | 141 |

| QLD | 342 | 243 | 264 | 278 | 297 | 244 | 146 |

| WA | 294 | 288 | 281 | 333 | 336 | 246 | 141 |

| TAS | 339 | 367 | 205 | 367 | 292 | 241 | 138 |

| SA | 269 | 393 | 255 | 292 | 402 | 214 | 154 |

| ACT | 327 | 299 | 431 | 338 | 321 | 267 | 186 |

| NT | 249 | 683 | 261 | 206 | 237 | 116 | 108 |

| Rurality | |||||||

| Major cities | 301 | 327 | 288 | 309 | 290 | 221 | 137 |

| Inner regional | 309 | 313 | 319 | 290 | 316 | 234 | 142 |

| Outer regional/Remote | 242 | 243 | 310 | 309 | 284 | 240 | 148 |

| IRSAD quintile | |||||||

| Very high | 203 | 214 | 244 | 203 | 247 | 186 | 128 |

| High | 231 | 300 | 285 | 299 | 263 | 221 | 143 |

| Middle | 263 | 319 | 290 | 302 | 320 | 222 | 142 |

| Low | 393 | 341 | 361 | 341 | 293 | 259 | 145 |

| Very low | 349 | 346 | 322 | 355 | 333 | 251 | 141 |

| Patient’s characteristics§ | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 278 | 272 | 272 | 259 | 271 | 211 | 137 |

| Female | 311 | 349 | 329 | 336 | 323 | 238 | 143 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–34 | 230 | 361 | 276 | 363 | 247 | 233 | 147 |

| 35–49 | 335 | 361 | 345 | 327 | 350 | 257 | 154 |

| 50–64 | 299 | 337 | 320 | 293 | 306 | 221 | 142 |

| 65–79 | 278 | 257 | 277 | 279 | 242 | 203 | 132 |

| 80+ | 336 | 371 | 326 | 336 | 379 | 249 | 143 |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | |||||||

| No | 302 | 319 | 308 | 303 | 303 | 224 | 139 |

| Yes | 442 | 376 | 415 | 405 | 381 | 274 | 158 |

| Not recorded | 245 | 315 | 278 | 296 | 279 | 232 | 146 |

| IRSAD quintile | |||||||

| Very high | 238 | 287 | 236 | 268 | 277 | 230 | 127 |

| High | 249 | 315 | 258 | 296 | 292 | 218 | 140 |

| Middle | 278 | 315 | 306 | 297 | 319 | 233 | 139 |

| Low | 358 | 333 | 360 | 323 | 303 | 216 | 134 |

| Very low | 343 | 337 | 343 | 330 | 308 | 232 | 159 |

*At least three consultations in any two consecutive years from 2012 to 2018.

†Values in parentheses represent the 95% CIs of the median time on opioids. The corresponding interquartile range values are 2012=91–1177; 2013=98–1214; 2014=98–1145; 2015=94–989; 2016=97–759; 2017=91–474; 2018=78–255.

‡Quantile regression models with all practice characteristics mutually adjusted. Values in ‘bold’ represent those associations with a p value <0.01.

§Quantile regression models with all patient characteristics mutually adjusted+adjustment for practice characteristics. Values in ‘bold’ represent those associations with a p value <0.01.

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; IRSAD, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage; MSK, musculoskeletal condition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

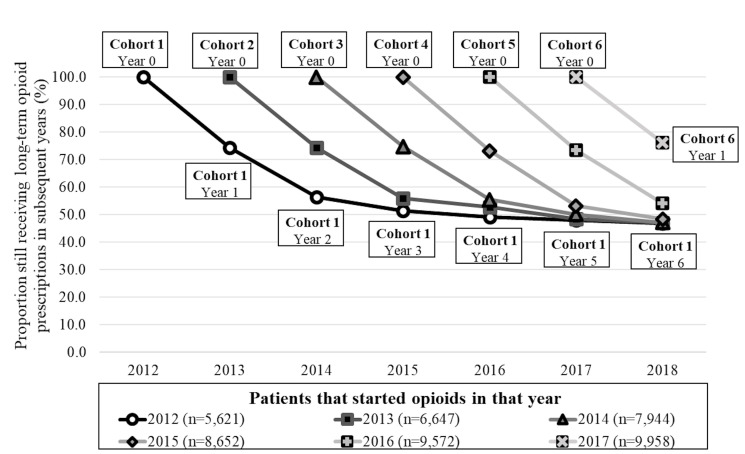

Figure 3 shows that 74.4% (95% CI 72.9 to 75.8) of those that started long-term opioid prescriptions in 2012 were still receiving these prescriptions after 1 year, while for those starting opioids in 2017, the proportion was 76.3% (95% CI 75.0 to 77.6). The proportion of patients in each cohort still on these prescriptions decreased to 54%–56% in year 2 and to 48%–51% in year 3 after starting long-term opioid prescriptions, remaining steady at around 48% in subsequent years.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients with musculoskeletal conditions starting long-term opioid prescriptions in any year that were still receiving these prescriptions in subsequent years. Period 2012–2018. Each connected line represents a different cohort followed over time. Numbers in parentheses (n) represent the total number of regular patients with a musculoskeletal condition that started long-term opioid prescriptions in that year.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Australian study that uses EMR from a national general practice database to investigate patterns of long-term opioid prescriptions for patients with MSK.27 Three main findings can be highlighted from the results. First, the overall prevalence of long-term opioid prescriptions increased between 2012 and 2018 as a consequence of the progressive rise of patients starting opioids in previous years rather than for an upsurge of incident cases. Second, factors associated with a higher incidence of long-term opioid prescription included increasing age, identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, living in a lower socioeconomic area or attending practices located in a rural setting or more disadvantaged areas. Finally, a longer duration of these episodes was observed among females or patients attending practices in lower socioeconomic areas.

The increase in the prevalence of long-term opioid prescriptions is consistent with other Australian studies using PBS data (9, 22).11 20 27 The observed increase in opioids prescriptions represents a substantial ongoing burden for Australia. In 2015–16, the total direct cost related to opioid use in Australia (ie, premature mortality, healthcare, criminal justice) was estimated to be $A15.76 billion, with additional $A26.8 associated the loss of quality of life of users and co-residents.44 Some authors suggest the increase in opioid use/prescription is related to the ageing population with higher rates of MSK, availability of slow-release opioid formulations and aggressive marketing of opioids by pharmaceutical companies.1 2 21 Moreover, the observed increase in Australia is probably related to the prescription of potent opioids. A previous study using PBS data found that between 2006 and 2015 weaker opioid use remained stable or declined, while there was a 238% increase in persons dispensed only strong opioids.20 Nonetheless, there is evidence that long-term opioid prescription for patients with MSK in the UK and North America reached a plateau around 2009–2011.21 22 45

Previous studies have also reported the incidence of opioid use has either decreased or remained unchanged in recent years, despite a rise in the prevalence.46–48 In consonance with these studies, we found a steady incidence between 2012 and 2016, followed by a lower incidence in 2018. Interestingly, the duration of long-term opioid prescription also declined in newly incident cases in 2017 and 2018 compared with the previous 5 years. Although results for 2018 might reflect an insufficient follow-up of incident cases in that year, it would not explain the findings observed in 2017. Recent education strategies among GPs and health policy changes may have helped reduce opioid initiation and duration when prescribing to someone affected by MSK.8 9 14 39 However, the increasing prevalence between 2012 and 2018 with an upsurging number of patients starting opioids in previous years (ie, ‘prevalent’ cases) may suggest insufficient pro-active opioid deprescribing is being undertaken. This conclusion is reinforced by the findings that 4 years or after starting long-term opioid prescriptions, half the patients continued to receive these prescriptions. Therefore, after all that time receiving opioids, it is likely that a considerable number of these patients became either dependent or possibly addicted to opioids.8 11 19

It is also overwhelming that sedative-hypnotics drugs (ie, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs) are being concomitantly prescribed with of opioids, increasing the risk of addiction, hospitalisations and deaths.19 49 50 Preliminary findings using MedicineInsight data show that the proportion of patients with MSK on long-term opioids prescriptions also receiving long-term benzodiazepines/Z-drugs prescriptions increased from 24.4% (95% CI 23.3 to 25.5) in 2012 to 30.0% (95% CI 29.0% to 30.9%). In contrast, among patients with MSK not receiving opioids, only 7.1% received long-term benzodiazepines/Z-drugs prescriptions in 2012 or 2018 (unpublished results). These findings help explain the substantial increase of opioid-induced deaths in Australia, which raised from 2.67 per 10 000 people in 2001 (514 out of 1038 total drug-induced deaths) to 4.36 per 100 000 people in 2018 (1088 out of 1740 total drug-induced deaths).44 49

Factors such as limited time of clinicians, insufficient training on deprescribing, restricted access to resources for monitoring patients using opioids are recognised barriers that affect strategies aiming to improve opioid prescription practices in primary care.1 51 Moreover, pharmaceutical companies’ aggressive marketing strategies also influence opioid prescription practices. In 2019, the Therapeutic Goods Administration fined Mundipharma $A302 400 for infringement notices related to misleading, imbalanced and inaccurate claims of promotional materials directed to Australian healthcare professionals, all of them related to nine opioid medicines marketed under the name Targin.52

Our finding that the elderly, patients living in lower socioeconomic areas, attending practices located in more disadvantaged settings or from rural and remote Australia have higher rates of long-term opioid prescription is consistent with British and American studies,21 22 53 as well as with results based on PBS data.11 30 31 These groups are also more likely to be affected by chronic MSK conditions.5 21 Perhaps, a maldistribution of support services or access to tertiary-based pain clinics could partially explain these differences,51 but further studies would be necessary to investigate the underlying causes in the Australian context.

Strengths and limitations

The study has significant strengths: a national sample including adult patients of all age groups, ethnicity or sex, and practices from all Australian states, socioeconomic areas or remoteness. Despite the novelty in the use of a national general practice database that allows the identification of patients with MSK, whether they were managed with opioids (incident and prevalent prescriptions) or not, and includes data on different associated factors, some limitations have to be recognised.

First, medicine-use information from MedicineInsight relates to records of GP prescribing, and not all prescriptions and repeats will be dispensed or taken by the patient. Therefore, results from this study reflect prescription patterns rather than opioid use.

Second, our study did not distinguish between the strength of preparations (ie, presented as either morphine equivalent doses or defined daily dose). However, previous studies found that up to 40% of the dispensed pain medications for non-cancer pain are potent opioids, and their use has increased over the years.15 17 20

Third, individuals attending multiple clinics for prescriptions are not tracked by MedicineInsight, and this may underestimate the real frequency of long-term opioid prescriptions. However, the observed trends and associations are consistent with the available literature.11 20–22 27 45

Finally, the place/professional that initiated the prescriptions (eg, ED, hospital, private specialist) cannot be investigated. Moreover, MedicineInsight does not provide details on the size and type of practices or characteristics of the doctors prescribing opioids (eg, junior doctor, specialist or GPs; years of experience and so on) Nonetheless, according to PBS data, half of the opioids prescribed in Australia are initiated by GPs17 and most patients with chronic pain requiring long-term opioid prescriptions are managed in primary care settings.51

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of long-term opioid prescribing for MSK conditions has increased in Australia between 2012 and 2018, despite a lower incidence and duration of these prescriptions in the last couple of years. This trend towards an increase in the prevalence of long-term opioid prescribing is of great concern, as current literature reports an overall escalation in the rates of opioid harms and deaths.8 9 11 14 Our study highlights the need for ongoing efforts to reduce the opioid burden, especially among those living and attending practices in more disadvantaged areas and considering the higher risk of adverse effect in elderly patients. This should come by reducing opioid initiation and by proactively deprescribing for suitable patients.8 14 While GPs are in an optimal position for this role,51 opioid stewardship is the responsibility of all prescribing medical practitioners and allied healthcare professionals dealing with MSK pain management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank NPS MedicineWise for their support in the development of this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript and are responsible for its content. NS and SB-T conceived the idea and planned this study. DG-C was responsible for data extraction and analysis, interpreting and presenting the results. SB-T and DG-C wrote the first draft and the revisions. NS contributed to the manuscript refinement. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from MedicineInsight and are not publicly available. Third parties may express an interest in the information collected through MedicineInsight. The provision of information in these instances undergoes a formal approval process and is guided by the MedicineInsight independent external Data Governance Committee. This Committee includes general practitioners, consumer advocates, privacy experts and researchers.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Adelaide exempted this study of an ethical review as only non-identifiable data were used. Access to the data for this study was approved by the MedicineInsight Data Governance Committee (project 2016-004 and 2019-029).

References

- 1.Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal Pain-Where to from here? Am J Public Health 2019;109:35–40. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggs AM, Shiffman J, Shawar YR, et al. Global health policy in the 21st century: challenges and opportunities to arrest the global disability burden from musculoskeletal health conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020;34:101549. 10.1016/j.berh.2020.101549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions across the life stages. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129547059 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke G, Valenti L, Glasziou P. Common general practice presentations and publication frequency. Aust Fam Physician 2013;42:65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Chica DA, Vanlint S, Hoon E, et al. Epidemiology of arthritis, chronic back pain, gout, osteoporosis, spondyloarthropathies and rheumatoid arthritis among 1.5 million patients in Australian general practice: NPS MedicineWise MedicineInsight dataset. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:20. 10.1186/s12891-018-1941-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Health-Care expenditure on arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions 2008–09. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129548392 [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Chica DA, Hill CL, Gill TK, et al. Individual diseases or clustering of health conditions? association between multiple chronic diseases and health-related quality of life in adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:244. 10.1186/s12955-017-0806-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australia P, Strategy NP. Pain management for all Australians. Australia: Pain Australia, 2014. http://www.painaustralia.org.au/improving-policy/national-pain-strategy [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2nd edn. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2018. https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Musculoskeletal/guideline-for-the-management-of-knee-and-hip-oa-2nd-edition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the space randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:872–82. 10.1001/jama.2018.0899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Opioid harm in Australia: and comparisons between Australia and Canada. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/opioid-harm-in-australia/contents/table-of-contents [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA 2011;305:1315–21. 10.1001/jama.2011.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA 2016;315:2415–23. 10.1001/jama.2016.7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1–49. 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashaye T, Hounsome N, Carnes D, et al. Opioid prescribing for chronic musculoskeletal pain in UK primary care: results from a cohort analysis of the COPERS trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019491. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Frenais FL, Bedder R, Vickerstaff V, et al. Temporal trends in analgesic use in long-term care facilities: a systematic review of international prescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:376–82. 10.1111/jgs.15238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalic S, Ilomäki J, Bell JS, et al. Prevalence and incidence of prescription opioid analgesic use in Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019;85:202–15. 10.1111/bcp.13792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manchikanti L, Sanapati J, Benyamin RM, et al. Reframing the prevention strategies of the opioid crisis: focusing on prescription opioids, fentanyl, and heroin epidemic. Pain Physician 2018;21:309–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shipton EA, Shipton EE, Shipton AJ. A review of the opioid epidemic: what do we do about it? Pain Ther 2018;7:23–36. 10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karanges EA, Buckley NA, Brett J, et al. Trends in opioid utilisation in Australia, 2006-2015: insights from multiple metrics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2018;27:504–12. 10.1002/pds.4369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedson J, Chen Y, Hayward RA, et al. Trends in long-term opioid prescribing in primary care patients with musculoskeletal conditions: an observational database study. Pain 2016;157:1525–31. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Xie F, Smith C, et al. Changing trends in opioid use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1733–40. 10.1002/art.40152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes K, Martins D, Juurlink D, et al. High-Dose opioid prescribing and Opioid-Related hospitalization: a population-based study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167479. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larochelle MR, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Trends in opioid prescribing and co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain: 2001-2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:885–92. 10.1002/pds.3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman MA, Komaiko KDR, Fung KZ, et al. Use of opioids and other analgesics by older adults in the United States, 1999-2010. Pain Med 2015;16:319–27. 10.1111/pme.12613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodard D, Van Demark RE. The opioid epidemic in 2017: are we making progress? S D Med 2017;70:467–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan PJ, Arroyo D, Pattullo C, et al. Trends in opioid prescribing in Australia: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev 2020;44:277–87. 10.1071/AH18245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollingworth SA, Symons M, Khatun M, et al. Prescribing databases can be used to monitor trends in opioid analgesic prescribing in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013;37:132–8. 10.1111/1753-6405.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gisev N, Pearson S-A, Karanges EA, et al. To what extent do data from pharmaceutical claims under-estimate opioid analgesic utilisation in Australia? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2018;27:550–5. 10.1002/pds.4329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Islam MM, McRae IS, Mazumdar S, et al. Prescription opioid dispensing in New South Wales, Australia: spatial and temporal variation. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2018;19:30. 10.1186/s40360-018-0219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Islam MM, Wollersheim D. Variation in prescription opioid dispensing across neighborhoods of diverse socioeconomic disadvantages in Victoria, Australia. Pharmaceuticals 2018;11:116. 10.3390/ph11040116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busingye D, Gianacas C, Pollack A, et al. Data resource profile: MedicineInsight, an Australian National primary health care database. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:1741–41h. 10.1093/ije/dyz147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badmus D, Menzies R. Using general practice data to monitor influenza vaccination coverage in the medically at risk: a data linkage study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031802. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardo CDO, Gonzalez-Chica D, Stocks N. Influenza-Like illness and antimicrobial prescribing in Australian general practice from 2015 to 2017: a national longitudinal study using the MedicineInsight dataset. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026396. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez-Chica D, Stocks N. Changes to the frequency and appropriateness of vitamin D testing after the introduction of new Medicare criteria for rebates in Australian general practice: evidence from 1.5 million patients in the NPS MedicineInsight database. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024797. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanam MA, Kitsos A, Stankovich J, et al. Chronic kidney disease monitoring in Australian general practice. Aust J Gen Pract 2019;48:132–7. 10.31128/AJGP-07-18-4630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee CMY, Mnatzaganian G, Woodward M, et al. Sex disparities in the management of coronary heart disease in general practices in Australia. Heart 2019;105:1898–904. 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SNOMED International . Snomed CT, 2020. Available: http://www.snomed.org/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 39.Australian Department of Health . The pharmaceutical benefits scheme. TGA prescription opioid regulatory reforms. Canberra, 2019. Available: https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-12/tga-prescription-opioid-regulatory-reforms [Accessed 30 Jan 2020].

- 40.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:85–92. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Cat. No. 2033.0.55.001 2018:Caneberra, Australia–Australian Bureau of Statistics http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001

- 42.Tajeu GS, Sen B, Allison DB, et al. Misuse of odds ratios in obesity literature: an empirical analysis of published studies. Obesity 2012;20:1726–31. 10.1038/oby.2012.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldstein BA, Bhavsar NA, Phelan M, et al. Controlling for informed presence bias due to the number of health encounters in an electronic health record. Am J Epidemiol 2016;184:847–55. 10.1093/aje/kww112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) . Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia. AIHW, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/phe/221/alcohol-tobacco-other-drugs-australia/contents/drug-types/non-medical-use-of-pharmaceutical-drugs [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han L, Allore H, Goulet J, et al. Opioid dosing trends over eight years among US Veterans with musculoskeletal disorders after returning from service in support of recent conflicts. Ann Epidemiol 2017;27:563–9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fassio V, Aspinall SL, Zhao X, et al. Trends in opioid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use and adverse events. Am J Manag Care 2018;24:e61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosher HJ, Krebs EE, Carrel M, et al. Trends in prevalent and incident opioid receipt: an observational study in veterans health administration 2004-2012. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:597–604. 10.1007/s11606-014-3143-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smolina K, Gladstone EJ, Rutherford K, et al. Patterns and trends in long-term opioid use for non-cancer pain in British Columbia, 2005-2012. Can J Public Health 2016;107:e404–9. 10.17269/CJPH.107.5413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Man N, Chrzanowska A, Dobbins T. Trends in drug induced death in Australia, 1997-2018. National drug and alcohol research centre, University of new South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia, 2019. Available: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/ndarc/resources/Drug%20Induced%20Deaths%20December%202019%20Bulletin_1.pdf [Accessed 20 Jan 2021].

- 50.Caughey GE, Gadzhanova S, Shakib S, et al. Concomitant prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines in Australia, 2012-2017. Med J Aust 2019;210:39–40. 10.5694/mja2.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheatle MD, Barker C. Improving opioid prescription practices and reducing patient risk in the primary care setting. J Pain Res 2014;7:301–11. 10.2147/JPR.S37306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woodley M. Mundipharma fined for misleading advertising of opioids. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners - News, 2019. Available: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/professional/mundipharma-fined-for-misleading-advertising-of-op [Accessed 21 Jan 2021].

- 53.Mordecai L, Reynolds C, Donaldson LJ, et al. Patterns of regional variation of opioid prescribing in primary care in England: a retrospective observational study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e225–33. 10.3399/bjgp18X695057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045418supp001.pdf (82KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-045418supp002.pdf (721.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from MedicineInsight and are not publicly available. Third parties may express an interest in the information collected through MedicineInsight. The provision of information in these instances undergoes a formal approval process and is guided by the MedicineInsight independent external Data Governance Committee. This Committee includes general practitioners, consumer advocates, privacy experts and researchers.