Abstract

The primary aim of this study was to examine sex differences in acute antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in rats. Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) was administered to adult Sprague–Dawley rats to induce pain and inflammation in one hindpaw; 2.5 h later, vehicle or a single dose of the NSAIDs ibuprofen (1.0–32 mg/kg) or ketoprofen (0.1–10 mg/kg), or the COX-2-preferring inhibitor celecoxib (1.0–10 mg/kg) was injected i.p. Mechanical allodynia, heat hyperalgesia, biased weight-bearing, and hindpaw thickness were assessed 0.5–24 h after drug injection. Ibuprofen and ketoprofen were more potent or efficacious in females than males in reducing mechanical allodynia and increasing weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw, and celecoxib was longer-acting in females than males on these endpoints. In contrast, ketoprofen and celecoxib were more potent or efficacious in males than females in reducing hindpaw edema. When administered 3 days rather than 2.5 h after CFA, ketoprofen (3.2–32 mg/kg) was minimally effective in attenuating mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia, and did not restore weight-bearing or significantly decrease hindpaw edema, with no sex differences in any effect. Neither celecoxib nor ketoprofen effects were significantly attenuated by cannabinoid receptor 1 or 2 (CB1 or CB2) antagonists in either sex. These results suggest that common NSAIDs administered shortly after induction of inflammation are more effective in females than males in regard to their antinociceptive effects, whereas their anti-inflammatory effects tend to favor males; effect sizes indicate that sex differences in NSAID effect may be functionally important in some cases.

Keywords: celecoxib, gender, ibuprofen, inflammatory pain, ketoprofen, rats, sex differences

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most widely used medications for the treatment of mild-to-moderate pain. In the United States, more than 29 million adults (12.1% of the population) were reported to be regular NSAID users in 2010, a 41% increase in use since 2005 (Zhou et al., 2014). Given known sex differences in inflammatory processes (Mirandola et al., 2015), sex differences in the potency or efficacy of NSAIDs might be expected. One of the earliest laboratory studies comparing NSAID effect in healthy humans reported that a single dose of ibuprofen (800 mg) produced analgesia against electrically induced pain in men but not women (Walker and Carmody, 1998). In contrast, against UVB-induced inflammatory pain in healthy humans, 800 mg ibuprofen increased heat pain threshold and tolerance with no sex difference (Sycha et al., 2003); however, with only four to six subjects/sex, this study likely lacked power for a valid sex comparison. No sex differences in the effect of ketorolac were observed in another larger laboratory study (n = 25/sex), but the single dose of drug tested did not produce significant analgesia against cold pressor pain, thus yielding an inconclusive result (Compton et al., 2003).

Sex differences in the pain-relieving effects of NSAIDs also have been examined in several clinical trials. In a secondary analysis of data from a large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, diclofenac (50 mg twice-daily) taken by patients with acute low back pain was more effective in women than men on one measure of recovery (pain score of 0 or 1 for seven consecutive days) but not the other (pain score of 0 or 1) (Hancock et al., 2009). Ryan et al. (2008) found an equivalent analgesic effect of 600 mg ibuprofen in men and women, when it was taken every 6 h for 24 h after oral surgery. Similarly, no significant sex differences in the analgesic effect were found in dental pain patients for several NSAIDs, including ibuprofen (with or without paracetamol) and etoricoxib, although at higher efficacy levels the authors note that sample sizes were likely inadequate to test for sex differences (Moore et al., 2011). Finally, a meta-analysis of the ibuprofen effect based on seven studies of postoperative dental pain revealed no significant sex difference in pain reduction over 6 h post-medication, although it was noted that baseline pain was higher in women than in men (Averbuch and Katzper, 2000). Thus, it is possible that ibuprofen was actually more effective in women than in men.

Animal studies are typically utilized to systematically characterize analgesic potency and efficacy, yet females and males have been compared in only a few animal studies of NSAID-induced antinociception. In one study, repeated ibuprofen treatment decreased swelling and reversed the lengthened meal duration induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) injection into the temporomandibular joint in female and male rats, but the ibuprofen effect was longer-lasting in females (Kerins et al., 2003). In another rat study, a single dose of diclofenac increased paw pressure thresholds in females but not males (Romanowska et al., 2008). Finally, knockout of the genes that encode cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) or −2 (COX-2) – the enzymes that NSAIDs inhibit – had some sexually dimorphic effects on allodynia, edema and joint destruction induced by CFA in mice (Chillingworth et al., 2006).

Given the widespread use of NSAIDs – both over-the-counter and by prescription in humans, as well as in veterinary medicine – the present study was designed to obtain comprehensive dose- and time-effect comparisons of NSAID-induced antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in female vs male rats using a model of persistent inflammatory pain. Time- and dose-effect curves were obtained for three NSAIDs: one nonspecific COX inhibitor (ibuprofen), one COX-1-preferring inhibitor (ketoprofen) and one COX-2-preferring inhibitor (celecoxib) (Cryer and Feldman, 1998; Varrassi et al., 2020). Rats were given an intraplantar (i.pl.) injection of CFA into one hindpaw, and multiple pain-related behaviors were assessed, including two measures of evoked pain as well as a measure of spontaneous pain. Hindpaw thickness was assessed as an index of edema. In a separate experiment, the most potent and efficacious NSAID, ketoprofen, was then compared between females and males 3 days after CFA injection, to determine if ketoprofen was still more effective in females than males under conditions of established inflammation.

Finally, a third experiment was conducted to test the hypothesis that acute NSAID-induced antinociception involves the endocannabinoid system. Several studies implicate the endocannabinoid system in the antinociceptive effects of NSAIDs in male rodents (e.g., Staniaszek et al., 2010; Telleria-Diaz et al., 2010). There is growing evidence of sex differences in the endocannabinoid system and in the antinociceptive effects of exogenous cannabinoids, with some studies demonstrating greater antinociceptive potency of cannabinoids in females than in males (for review, see Cooper and Craft, 2018). Thus, a separate experiment was conducted to determine whether NSAID-induced antinociceptive effects involve cannabinoid receptor activation in both sexes.

Methods

Subjects

Adult (60–100 days old) male and female Sprague–Dawley rats were used (sample size/sex/group is reported below and in each figure legend). Rats were bred in-house from Envigo (formerly Harlan) stock (Livermore, California, USA), and housed under a 12:12-h light:dark cycle (lights on at 06:00) in a vivarium room maintained at 21 ± 2°C. Male and female rats were typically housed in same-sex pairs in the same vivarium room but with males and females on different racks. TekFresh bedding (Envigo, Denver, Colorado, USA) was used in the cages, and rats had ad libitum access to food and water except during testing. Rats were tested during the light part of the cycle, between 08:00 and 16:00. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University, and rats were treated in accordance with the National Research Council, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011).

Apparatus

An electronic von Frey aesthesiometer (IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, California, USA) was used to measure the mechanical threshold. To measure sensitivity to noxious heat, the Hargreaves test (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy) was used, with an infrared intensity of 52 mW/cm2 and a cutoff of 31 s. Tests were conducted on both the left and right paws, with approximately half of the rats in each treatment group being tested on the left hindpaw first and half on the right hindpaw first. To assess hindpaw weight-bearing, an incapacitance meter (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Illinois, USA) was used. To assess edema, dorsal-ventral hindpaw thickness was measured in millimeters with calipers.

Behavioral procedures

Experiment 1: dose- and time-effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception against acute inflammatory pain

Rats were weighed and then lightly anesthetized with isoflurane; paw inflammation/pain was induced with an i.pl. injection of CFA into the right hindpaw. Two and one half hours later, vehicle [saline or 50% polyethylene glycol (PEG); n = 11/sex] or a single dose of ibuprofen (1.0, 3.2, 10 or 32 mg/kg; n = 9–11/sex/dose), ketoprofen (0.1, 0.32, 1.0, 3.2 or 10 mg/kg; n = 9–10/sex/dose) or celecoxib (1.0, 3.2 or 10 mg/kg; n = 9/sex/dose) was injected i.p. Each rat was placed into a hanging wire cage (that allowed access to the plantar surface of the hindpaws) for approximately 15 min. At 0.5 h post-NSAID injection, the von Frey test was conducted: the force required to induce hindpaw withdrawal, in grams, was recorded for each hindpaw (three trials each hindpaw, spaced approximately 30 s apart). Next, the Hargreaves test was conducted: latency to withdraw each hindpaw from the heat stimulus was recorded in seconds (three trials each hindpaw, spaced approximately 30 s apart). Then, weight-bearing on each hindpaw was simultaneously recorded (three trials, spaced approximately 30 s apart). Finally, the maximum dorsal-ventral hindpaw thickness was taken as a measure of edema, using calipers. All tests were conducted again, in the same order, at 1.5, 3.5, 6 and 24 h after NSAID injection.

Experiment 2: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception against established inflammatory pain

A separate group of rats was used to examine NSAID effect under conditions of persistent inflammation. Three days after i.pl. CFA treatment, rats were injected i.p. with vehicle or a single dose of ketoprofen (3.2, 10 or 32 mg/kg; n = 10/sex/dose). Nociception was assessed as described above using the von Frey, Hargreaves, and weight-bearing tests at 2 h postinjection, and paw thickness was measured at 3 h postinjection. These time points were chosen based on maximal or near-maximal ketoprofen effects observed in Experiment 1.

Experiment 3: cannabinoid receptor mediation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception

Procedures were the same as in Experiment 1, except rats were injected i.p. with vehicle (1:1:8 ethanol:cremaphor:saline), the CB1 receptor-selective antagonist rimonabant (1.0 mg/kg), or the CB2 receptor-selective antagonist SR144528 (1.0 mg/kg), immediately before vehicle (saline or 50% PEG), 10 mg/kg celecoxib or 3.2 mg/kg ketoprofen (n = 8–13/sex/treatment group). Antagonist doses were based on a previous study demonstrating antagonism of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the CFA model, using 1.0 mg/kg of each antagonist (Craft et al., 2013). Rats were tested on behavioral assays as described for Experiment 1, at 0.5, 1.5, 3.5 and 6 h post-NSAID injection. Experimenters were blind to the antagonist condition.

Determination of estrous stage

In Experiment 1, immediately after behavioral testing on the first day (after testing at the 6-h time point), a vaginal cell sample was obtained by lavage from each of the females. Slides were later stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and scored as follows: proestrus was identified by the predominance (approximately 75% or more of cells in the sample) of nucleated epithelial cells; proestrus to estrus (sometimes referred to as ‘late proestrus’) was identified by approximately equal proportions of nucleated and cornified epithelial cells; estrus was identified by the presence of dense sheets of cornified epithelial cells; and diestrus was identified by scattered nucleated and cornified epithelial cells and leukocytes (diestrus-1), or leukocytes with very few epithelial cells (diestrus-2) (Freeman, 1988).

Drugs

Ibuprofen (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in saline, which served as the vehicle. Ketoprofen (Sigma-Aldrich) and celecoxib (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) were dissolved in PEG to which distilled water was added for a final PEG concentration of 50%; some rats in the vehicle-treated group were tested with this vehicle instead of saline. All NSAIDs were administered i.p. in volumes of 1–2 ml/kg. Rimonabant (SR141716A) and SR144528 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) were dissolved in 1:1:8 ethanol:cremaphor:saline, which served as the vehicle; antagonists were administered i.p. in volumes of 1 ml/kg. CFA (0.1 ml of 1 mg/ml killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis suspended in mineral oil; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the right plantar hindpaw.

Data analysis

At each time point after drug injection, the mean of the three trials was calculated for each paw on the von Frey, Hargreaves and weight-bearing tests. Baseline sex comparisons (in vehicle-treated rats) were conducted by ANOVA, with variables of sex (female vs male), paw (left vs right, repeated) and time (five levels, repeated); raw data are shown in Table 1. Because individual differences are typical for measures that are body size-dependent (e.g., weight-bearing and paw thickness), raw data for each vehicle- and drug-treated rat were transformed to % of each rat’s control (left) hindpaw: [score in right (CFA-injected) hindpaw/score in left (uninjected) hindpaw] × 100. These percent-of-control-paw data were then analyzed by ANOVA, with variables of sex (two levels), dose (4–6 levels) and time (five levels, repeated). There were significant sex differences in several measures in vehicle-treated controls (see Results, Fig. 1); thus, before comparing drug effects between the sexes, drug data were further transformed by subtracting the same-sex, the group mean vehicle score from each individual drug-treated rat’s score, at each time point, for each measure. The time course of effects using these transformed data is plotted for one dose of each drug in Figs. 2–4 (Experiment 1). An area-under-the-curve (AUC) value was also derived from each rat’s time-effect curve using the trapezoidal rule, to summarize time course effects across multiple doses on the first day (0.5–6 h postinjection); AUC values are shown in Figs. 5–7 (Experiment 1) and in Fig. 8 (Experiment 2). AUC values for the four dependent measures were analyzed by MANOVA, with variables of sex (two levels) and NSAID dose (4–6 levels). Finally, to compare drug potency between the sexes in Experiment 1, drug data at the time of maximal observed effect (3.5 h postinjection) were transformed to % maximum possible effect (%MPE): for example, [(mechanical threshold (right paw) in drug-treated rat − mean mechanical threshold (right paw) in vehicle-treated rats of the same sex)/[mean mechanical threshold (left paw) in vehicle-treated rats of the same sex − mean mechanical threshold (right paw) in vehicle-treated rats of the same sex)] × 100. Percent MPE data were compared between the sexes using a two-way ANOVA, with variables of sex (two levels) and NSAID dose (3–5 levels).

Table 1.

Raw scores on nociception and paw thickness tests in vehicle-treated control rats

| Test | 0.5 h | 1.5 h | 3.5 h | 6 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| von Frey (g) | |||||

| Females | |||||

| CFA paw | 35.4 ± 3.6 | 16.8 ± 2.9 | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 11.3 ± 2.9 | 7.9 ± 1.5 |

| Untreated paw | 75.0 ± 6.0 | 78.6 ± 4.5 | 97.1 ± 2.3 | 99.4 ± 2.5 | 86.6 ± 3.8 |

| Males | |||||

| CFA paw | 43.0 ± 5.8 | 30.6 ± 3.0 | 14.6 ± 2.4 | 12.3 ± 1.6 | 17.6 ± 3.9 |

| Untreated paw | 88.6 ± 4.6 | 95.3 ± 5.8 | 101.5 ± 5.1 | 112.1 ± 4.8 | 107.0 ± 2.8 |

| Hargreaves (s) | |||||

| Females | |||||

| CFA paw | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| Untreated paw | 14.7 ± 1.0 | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 14.2 ± 1.2 | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 12.0 ± 1.1 |

| Males | |||||

| CFA paw | 12.8 ± 2.4 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.7 |

| Untreated paw | 16.1 ± 1.9 | 14.8 ± 1.0 | 16.7 ± 1.7 | 15.2 ± 1.4 | 17.0 ± 1.2 |

| Weight-bearing (g) | |||||

| Females | |||||

| CFA paw | 81.2 ± 4.3 | 44.6 ± 3.1 | 17.5 ± 3.6 | 10.5 ± 1.6 | 27.1 ± 3.6 |

| Untreated paw | 115.6 ± 5.5 | 134.6 ± 6.7 | 145.7 ± 7.7 | 135.7 ± 6.4 | 146.4 ± 6.7 |

| Males | |||||

| CFA paw | 124.2 ± 8.7 | 109.5 ± 12.6 | 45.6 ± 5.8 | 35.2 ± 4.2 | 78.6 ±14.0 |

| Untreated paw | 145.8 ± 10.0 | 142.8 ± 6.6 | 174.1 ± 10.8 | 176.1 ± 7.6 | 160.8 ± 8.1 |

| Paw thickness (mm) | |||||

| Females | |||||

| CFA paw | 6.86 ± 0.13 | 7.59 ± 0.15 | 9.38 ± 0.15 | 10.71 ± 0.16 | 10.66 ± 0.14 |

| Untreated paw | 4.89 ± 0.07 | 4.89 ± 0.06 | 5.00 ± 0.06 | 5.01 ± 0.06 | 4.97 ± 0.05 |

| Males | |||||

| CFA paw | 7.92 ± 0.20 | 8.92 ± 0.24 | 10.60 ± 0.21 | 11.80 ± 0.19 | 11.76 ± 0.15 |

| Untreated paw | 5.99 ± 0.04 | 6.00 ± 0.04 | 6.06 ± 0.04 | 6.02 ± 0.05 | 6.08 ± 0.04 |

Mean ± 1 S.E.M. of n = 11/sex.

CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Fig. 1.

Nociception and edema scores in vehicle-treated control rats. CFA was injected into the right hindpaw, and 2.5 h later vehicle was administered i.p. At 0.5–24 h later, mechanical threshold (von Frey test; a), latency to withdraw from noxious heat (Hargreaves test; b), weight-bearing on the CFA-injected hindpaw (c), and maximum dorsal-ventral thickness of the CFA-injected hindpaw (d) were assessed. All scores are the CFA-injected paw relative to the uninjected paw (right paw score/left paw score × 100), to adjust for individual differences in body size; see Table 1 for raw data. Each symbol is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 11 females or 11 males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

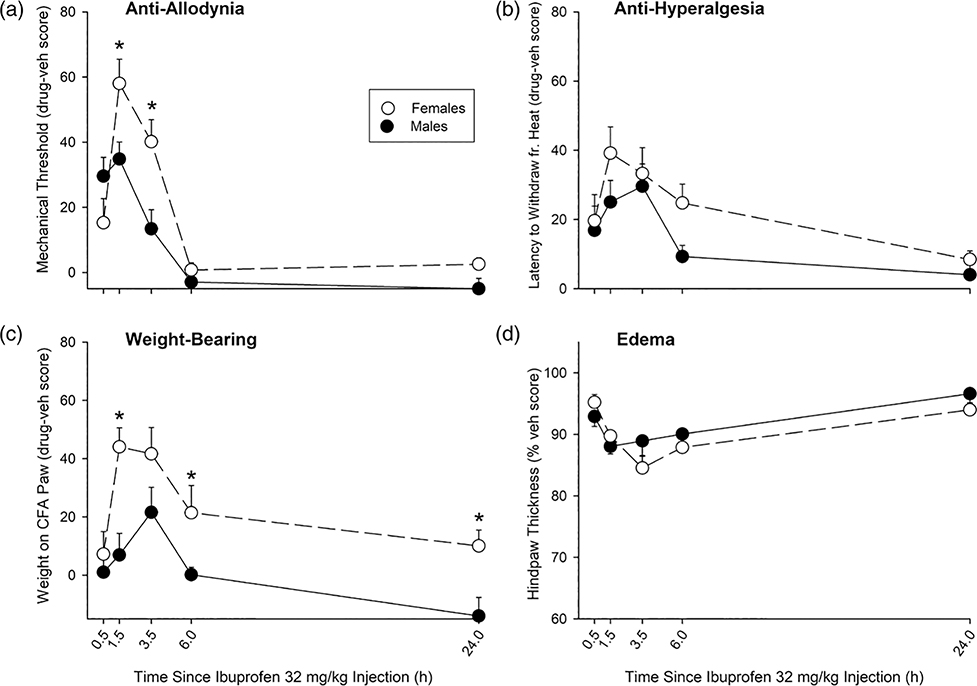

Fig. 2.

Time course of ibuprofen effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats under conditions of acute inflammatory pain. CFA was injected into the right hindpaw, and 2.5 h later ibuprofen was administered i.p. At 0.5–24 h later, mechanical threshold (von Frey test; a), withdrawal from noxious heat (Hargreaves test; b), weight-bearing on the CFA-injected hindpaw (c), and maximum dorsal-ventral thickness of the CFA-injected hindpaw (d) were assessed. For clarity, only the highest dose of ibuprofen tested, 32 mg/kg, is plotted. Scores in vehicle-treated rats were subtracted from scores of ibuprofen-treated rats (a–c), or drug scores are % of vehicle scores (d), to adjust for sex differences in vehicle-treated controls (see Fig. 1); AUC values below 0 indicate that NSAID-treated rats had scores (e.g., mechanical thresholds) lower than that of vehicle-treated controls. AUC values for all ibuprofen doses are shown in Fig. 5. Each symbol is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 11 females or 11 males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. AUC, area under the curve; CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Fig. 4.

Time course of celecoxib effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats under conditions of acute inflammatory pain. For clarity, only the highest dose of celecoxib tested, 10 mg/kg, is plotted; AUC values for all doses are shown in Fig. 7. Other details are the same as in Fig. 2. Each symbol is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of nine females or nine males.

Fig. 5.

Ibuprofen dose-effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats: ibuprofen’s antiallodynic (a) and antihyperalgesic (b) effects, its ability to restore weight-bearing (c), and reduce edema (d) of the CFA-injected paw. AUC values were derived from time-effect curves on the first day (0.5–6 h postinjection); AUC scores in vehicle-treated rats were subtracted from AUC scores of ibuprofen-treated rats, to adjust for sex differences in vehicle-treated controls. Each bar is the mean + 1 S.E.M. of 9–11 females or 9–11 males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. AUC, area under the curve; CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Fig. 7.

Celecoxib dose-effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats: celecoxib’s antiallodynic (a) and antihyperalgesic (b) effects, its ability to restore weight-bearing (c), and to reduce edema (d) of the CFA-injected paw. Other details and vehicle data are the same as shown in Fig. 5. Each bar is the mean + 1 S.E.M. of nine females or nine males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Fig. 8.

Ketoprofen dose-effect in female vs male rats under conditions of established inflammatory pain. CFA was injected into the right hindpaw, and 3 days later vehicle or ketoprofen was administered i.p. Two hours later, mechanical threshold (von Frey test; a), withdrawal from noxious heat (Hargreaves test; b) and weight-bearing on the CFA-injected hindpaw (c) were assessed; the maximum dorsal-ventral thickness of the CFA-injected hindpaw (d) was measured at 3 h postinjection. Other details are the same as in Fig. 2. Each point is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 10 females or 10 males. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

In Experiment 2, ketoprofen data at the single time point assessed were transformed to %-of-control-paw for each rat, in the same way as described for Experiment 1. The second transformation (subtracting mean vehicle score from each drug score) was not done because there were sex differences in only one dependent measure in vehicle-treated controls in this experiment. Percent-of-control-paw data were analyzed by MANOVA, with factors of sex (two levels) and ketoprofen dose (four levels).

In Experiment 3, drug data were transformed as described for Experiment 1, and repeated measures ANOVA were conducted on time course data, with between-subjects factors of sex (two levels), antagonist (three levels), NSAID dose (two levels) and within-subjects measure of time (four levels). Separate analyses were conducted on celecoxib data and on ketoprofen data, but the same control groups were used in each analysis (vehicle+vehicle, rimonabant+vehicle, SR144528+vehicle). For all analyses, P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Dunnett’s test was used to compare multiple drug doses to a single vehicle control group, and t-tests with Bonferroni correction were used to compare sexes at a single time point or dose. For all repeated measures ANOVAs, Mauchley’s test of sphericity was conducted to test for homogeneity of variance; if this assumption was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser adjusted df, F and P values are reported. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0.

Results

Experiment 1: dose- and time-effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception against acute inflammatory pain

The effects of CFA in female vs male vehicle-treated controls are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. The time course of NSAID effects from 0.5 to 24 h postinjection produced by one dose of each NSAID tested is shown in Figs. 2–4. AUC values derived from time-effect curves on the first day of testing only (0.5–6 h postinjection) for all doses of each NSAID are shown in Figs. 5–7, to illustrate acute, dose-related NSAID effects in females vs males. To illustrate sex differences in NSAID potency, dose-effect curves at the time of maximal observed effect (3.5 h) are plotted in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Potency of ketoprofen, celecoxib, and ibuprofen at the time of maximal observed effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats. Percent MPE data were derived from time-effect curves at the 3.5-h time point (see Methods). Each point is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 9–11 female or 9–11 male rats. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant; MPE, maximum possible effect.

Complete Freund’s adjuvant effects in vehicle-treated controls

I.pl. CFA decreased mechanical and noxious heat thresholds and weight-bearing on the injected hindpaw, and increased edema in a time-dependent manner. All of these effects were apparent when testing commenced 3 h after i.pl. CFA injection (0.5 h after i.p. vehicle injection), and reached maximum by 6–8.5 h after CFA injection (3.5–6 h after vehicle injection); raw data are shown in Table 1, and transformed data (see Data analysis) are shown in Fig. 1. Females and males showed very similar trajectories of CFA-induced pain-related behaviors and hindpaw edema. However, weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw decreased significantly more in females than males (Sex: F1,20 = 24.59, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.551; Sex × Time: F2.4,47.2 = 3.81, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.160; Fig. 1c), and increases in paw thickness were significantly greater in females than in males (Sex: F1,20 = 15.03, P = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.429; Sex × Time: F4,80 = 3.85, P < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.161; Fig. 1d). Thus, drug data were adjusted before analysis of sex differences in NSAID effects (see Data analysis).

Ibuprofen

Analysis of 0.5–24 h time course data for all doses (1.0–32 mg/kg) showed that ibuprofen increased mechanical threshold in a time-dependent manner, and its effect was greater in females than males at some doses and time points (Sex × Dose × Time: F10.5,239.8 = 2.94, P = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.115); the effect of 32 mg/kg ibuprofen on mechanical threshold over 24 h is shown in Fig. 2a. Analysis of complete time course data for all doses also showed that ibuprofen increased latency to withdraw from noxious heat, an effect that peaked 1.5–3.5 h postinjection (Dose × Time: F12.3,280.4 = 3.37, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.129), with no sex difference (Sex: F1,91 = 3.72, NS). The effect of 32 mg/kg ibuprofen on heat hyperalgesia over 24 h is shown in Fig. 2b. Ibuprofen also increased weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F12.4,283 = 3.36, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.129), with a greater effect in females than in males at several time points (Sex × Time: F3.1,283 = 9.53, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.095); the effect of 32 mg/kg is shown in Fig. 2c. Finally, ibuprofen decreased hindpaw thickness in a dose-and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F13.2,300.8 = 4.35, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.161), with a slightly later peak effect in females compared to males (Sex × Time: F3.3,300.8 = 3.27, P < 0.025, partial η2 = 0.035); the time course of effect for 32 mg/kg is shown in Fig. 2d.

Figure 5 shows AUC values derived from time-effect curves on the first day (0.5–6 h post-NSAID injection) for all doses of ibuprofen tested. Ibuprofen increased mechanical thresholds more in females than in males at some doses (Sex × Dose: F4,91 = 3.03, P < 0.025, partial η2 = 0.117; Fig. 5a). Ibuprofen also lengthened latency to respond to noxious heat more in females than in males (Sex: F1,91 = 3.82, P = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.040; Dose: F4,91 = 12.57, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.356), although this sex difference was not statistically significant at any single dose (Fig. 5b). Ibuprofen also increased weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw more in females than in males (Sex: F1,91 = 16.07, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.150; Dose: F4,91 = 9.60, P = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.297; Fig. 5c), but decreased hindpaw thickness with no sex difference (Dose: F4,91 = 10.57, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.317; Fig. 5d).

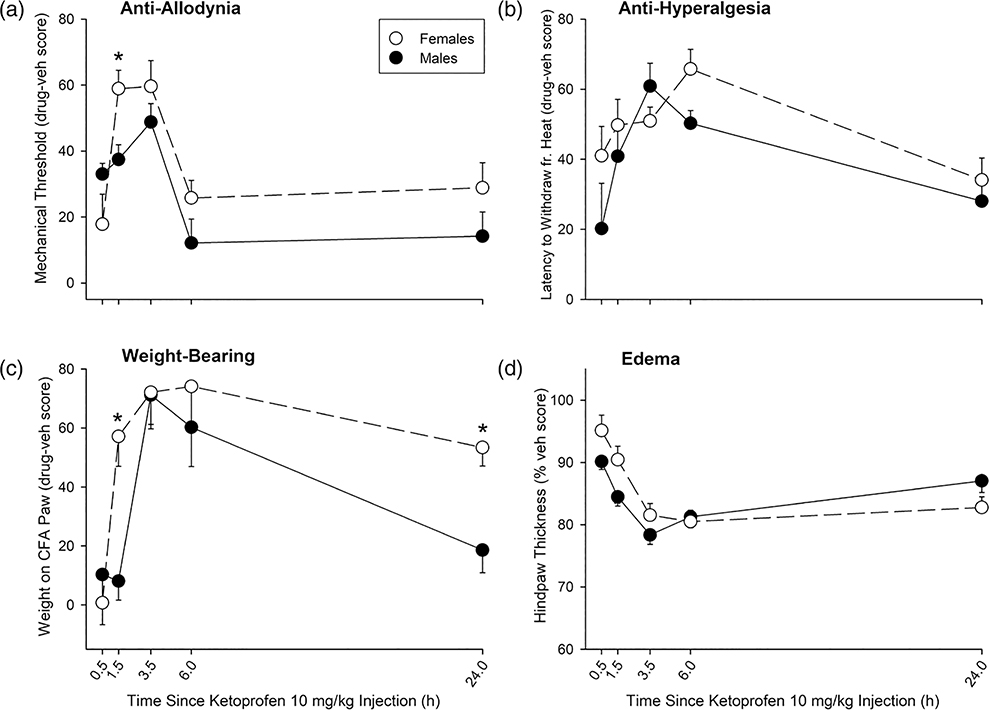

Ketoprofen

Analysis of time course data for all doses (0.1–10 mg/kg) showed that ketoprofen increased the mechanical threshold in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F15.7,328.9 = 6.42, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.234), and its effect was greater in females than in males at some time points (Sex × Time: F3.1,328.9 = 8.93, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.078). Specifically, ketoprofen was more effective in females than in males at 1.5 h (P < 0.001) and 3.5 h postinjection (P < 0.025). The time course of ketoprofen (10 mg/kg) effect on the mechanical threshold is shown in Fig. 3a. Analysis of time course data for all doses also showed that ketoprofen increased latency to withdraw from noxious heat in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F15.2,320.2 = 2.91, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.122), with slightly different peak times of effect in females compared to males (Sex × Time: F3,320.2 = 3.10, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.029). The time course of effect for 10 mg/kg ketoprofen on the Hargreaves test is shown in Fig. 3b. Ketoprofen also increased weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw with greater effects in females at some doses and time points (Sex × Dose × Time: F20,420 = 1.61, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.071). Specifically, ketoprofen-induced increases in hindpaw weight-bearing were greater in females than males at 1.5 h postinjection (P = 0.001) and 24 h postinjection (P < 0.005). The effect of the highest dose of ketoprofen tested, 10 mg/kg, on weight-bearing is shown in Fig. 3c. Finally, ketoprofen decreased hindpaw thickness in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F17,356.5 = 4.64, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.181), with greater effects in males than in females at early time points (Sex × Time: F3.4,356.5 = 5.92, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.053); the time course of effect for 10 mg/kg is shown in Fig. 3d.

Fig. 3.

Time course of ketoprofen effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats under conditions of acute inflammatory pain. For clarity, only the highest dose of ketoprofen tested, 10 mg/kg, is plotted; AUC values for all doses are shown in Fig. 6. Other details are the same as in Fig. 2. Each symbol is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 10 females or nine males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. AUC, area under the curve; CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Figure 6 shows AUC values derived from time-effect curves on the first day (0.5–6 h postinjection) for all doses of ketoprofen tested. Ketoprofen increased mechanical thresholds more in females than in males (Sex: F1,105 = 14.28, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.120; Dose: F5,105 = 32.87, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.610; Fig. 6a). Although low doses of ketoprofen also appeared to produce greater effects in females than in males on the Hargreaves test, sex differences on this endpoint were not significant (Dose: F5,105 = 17.19, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.450; Fig. 6b). However, ketoprofen’s effect on hindpaw weight-bearing was greater in females than in males at several lower doses (Sex × Dose: F5,105 = 2.49, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.106; Fig. 6c). Ketoprofen-induced reductions in hindpaw thickness were similar in females and in males (Dose: F5,105 = 14.98, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.416; no Sex × Dose interaction; Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Ketoprofen dose-effect in CFA-treated female vs male rats: ketoprofen’s antiallodynic (a) and antihyperalgesic (b) effects, its ability to restore weight-bearing (c), and to reduce edema (d) of the CFA-injected paw. Other details and vehicle data are the same as shown in Fig. 5. Each bar is the mean + 1 S.E.M. of 9–10 females or 9–10 males. *Significant sex difference, P ≤ 0.05. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Celecoxib

Analysis of 0.5–24 h time course data for all doses (1.0–10 mg/kg) showed that celecoxib increased the mechanical threshold in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F7.9,179.8 = 4.17, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.155), with greater effects in females than in males at some time points (Sex × Time: F2.6,179.8 = 4.11, P = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.057). Post-hoc tests at each time point showed a sex difference only at 24 h (P < 0.001): at that time, a small celecoxib effect persisted in females but not in males. The time course of celecoxib effect on mechanical threshold is shown in Fig. 4a (for clarity, only the highest dose tested, 10 mg/kg, is shown). Analysis of time course data for all doses also showed that celecoxib increased latency to withdraw from noxious heat in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F9.4,212 = 2.02, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.082), with no sex differences; the time course for 10 mg/kg celecoxib is shown in Fig. 4b. Celecoxib also increased weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Dose × Time: F10.7,242.6 = 5.26, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.188), with greater effects in females than in males at some time points (Sex × Time: F3.6,242.6 = 5.62, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.076). Post-hoc tests showed significantly greater celecoxib effects in females than in males at the 1.5- and 24-h time points (P’s ≤ 0.001); that is, celecoxib had an earlier onset and longer duration of action in females than in males on this pain-related behavior. The time course for 10 mg/kg celecoxib on weight-bearing is shown in Fig. 4c. Finally, analysis of time course data for all doses showed that celecoxib decreased hindpaw thickness in a dose-dependent manner (Dose: F3,68 = 13.79, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.378), with greater effects in males than in females at some time points (Sex × Time: F3.3,221.1 = 5.82, P = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.079). Post-hoc tests showed that celecoxib-induced decreases in paw thickness were greater in males than in females at the 1.5-h time point (P < 0.005). The time course for 10 mg/kg celecoxib on hindpaw thickness is shown in Fig. 4d.

Figure 7 shows AUC values derived from time-effect curves on the first day (0.5–6 h postinjection) for all doses of celecoxib tested. Analysis of AUC values indicated that celecoxib increased mechanical thresholds (Dose: F3,68 = 12.84, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.362; Fig. 7a), withdrawal latencies to noxious heat (Dose: F3,68 = 8.87, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.281; Fig. 7b), and weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw (Dose: F3,68 = 13.15, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.367; Fig. 7c) with no sex differences, but reduced hindpaw thickness more in males than in females (Sex: F1,68 = 6.41, P < 0.025, partial η2 = 0.086; Dose: F3,68 = 6.84, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.232; Fig. 7d).

Sex differences in potency of antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: dose-effect curves at time of maximal effect

Figure 9 shows dose-effect curves for all three NSAIDs at 3.5 h postinjection, the time at which drug effects were maximal or near-maximal (see Figs. 2–4). Overall, ketoprofen was the most potent and efficacious NSAID and ibuprofen was the least potent, on all three nociceptive measures and on hindpaw thickness, the measure of edema. Additionally, all NSAIDs tended to be more efficacious in increasing weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw than in reducing mechanical allodynia or hindpaw edema. Analysis of dose-effect data at the time of peak observed effect showed that in terms of antiallodynic effects, ketoprofen was more potent in females than males (Sex: F1,85 = 5.44, P < 0.025, partial η2 = 0.062), whereas ibuprofen was more efficacious in females than in males at the highest dose tested (Sex × Dose: F3,71 = 3.79, P < 0.025, partial η2 = 0.138), and the celecoxib effect did not differ between the sexes (Fig. 9a). In regard to antihyperalgesic effects, there were no significant sex differences at the time of peak observed effect for any NSAID (Fig. 9b). In regard to increasing weight-bearing on the inflamed hindpaw, ketoprofen was more potent but not more efficacious in females than in males (Sex × Dose: F4,85 = 2.58, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.107), whereas there were no sex differences for the other two NSAIDs (Fig. 9c). Finally, in regard to edema reduction at the time of peak observed effect, both ketoprofen (Sex: F1,85 = 4.47, P < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.069) and celecoxib (Sex: F1,48 = 9.22, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.190) were more potent and efficacious in males than in females, whereas ibuprofen effect did not differ between the sexes (Fig. 9d).

Estrous stage

Vaginal lavage samples taken after the 6-h time point in Experiment 1 showed that approximately 11% of females were in early proestrus, 12% were in late proestrus, 19% were in estrus, and 58% were in diestrus-1 or −2. Analysis of time course data from females on the first day of testing (0.5–6 h time points) with estrous stage entered as the covariate revealed no significant effect of estrous stage on any measure, for any of the NSAIDs, with one exception. Estrous stage significantly influenced paw thickness in the celecoxib experiment, at some time points (Estrous × Time: F3,99 = 5.37, P < 0.005, partial η2 = 0.140). Specifically, celecoxib-induced decreases in paw thickness were greatest in females that were in estrus (data not shown). However, the number of celecoxib-treated rats in each estrous stage was low, and the distribution of females in various estrous stages tested at each dose was uneven (most estrous females were in the 10 mg/kg group).

Experiment 2: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception against established inflammatory pain

A separate experiment was conducted to determine whether the NSAID that was the most potent and efficacious under conditions of acute inflammation, ketoprofen, was differentially effective in females and males once inflammation was well established. Three days after i.pl. CFA, vehicle-treated rats showed mechanical allodynia, heat hyperalgesia, biased weight-bearing and increased thickness of the CFA-injected paw (Fig. 8a–d, see bars at 0 mg/kg), although effects were smaller than those observed at 3.5–24 h after CFA injection in Experiment 1 (compare to Fig. 1). There were no sex differences in CFA’s effects at 3 days postinjection, except greater hindpaw thickness in females than in males (F1,72 = 30.92, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.300; Fig. 8d), similar to the sex difference observed during the first 24 h after CFA injection on this measure (Fig. 1d). Under these conditions of established inflammation, higher ketoprofen doses were needed (3.2–32 mg/kg) to produce antinociception compared to those that were effective against acute inflammatory pain (0.1–1.0 mg/kg in Experiment 1). When administered 3 days after CFA, ketoprofen dose-dependently attenuated CFA-induced mechanical allodynia (Dose: F3,72 = 4.08, P = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.145; Fig. 8a) and heat hyperalgesia (Dose: F3,72 = 2.75, P = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.103; Fig. 8b), but did not attenuate biased weight-bearing (Fig. 8c), and there were no sex differences in any of these effects. Ketoprofen reduced paw thickness only slightly (Dose: F3,72 = 2.60, NS, partial η2 = 0.098). Thus, whereas under conditions of acute inflammation, ketoprofen was more potent in females than in males in reducing pain-related behaviors, and under conditions of persistent inflammation, sex differences were not observed.

Experiment 3: cannabinoid receptor mediation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug antinociception

To determine whether NSAID effects are mediated by cannabinoid receptors, a separate group of CFA-treated, male and female rats was pretreated with vehicle, the CB1R-selective antagonist rimonabant (1.0 mg/kg), or the CB2R-selective antagonist SR144528 (1.0 mg/kg), immediately before receiving vehicle, celecoxib 10 mg/kg, or ketoprofen 3.2 mg/kg. As in Experiment 1, celecoxib alleviated CFA-induced decreases in mechanical threshold (F1,106 = 8.45, P < 0.005; partial η2 = 0.074) and latency to respond to noxious heat (F1,106 = 28.80, P < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.214), as well as increasing weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw (F1,106 = 72.28, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.405), and reducing edema (F1,106 = 12.96, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.109). Figure 10 depicts the effects of rimonabant and SR144528 in combination with celecoxib in males, the only sex in which there appeared to be possible evidence of antagonism. Cannabinoid antagonists partially reduced celecoxib effects on weight-bearing, although this effect was not significant (antagonist: F2,29 = 2.93, NS, partial η2 = 0.168; Fig. 10c). The antagonists also appeared to block celecoxib’s effect on hindpaw edema at 0.5–1.5 h postinjection, but again this effect was not significant (Antagonist × Time: F4.3,63.0 = 1.21, NS, partial η2 = 0.077; Fig. 10d). A higher dose of each antagonist (3 mg/kg) was subsequently examined in combination with 10 mg/kg celecoxib, but the higher antagonist dose also did not significantly attenuate any celecoxib effect, in either sex (data not shown).

Fig. 10.

Effects of 10 mg/kg celecoxib in combination with vehicle, 1 mg/kg rimonabant, or 1 mg/kg SR144528, in male rats. CFA was injected into the right hindpaw, and 2.5 h later drugs were co-administered i.p. At 0.5–6 h later, mechanical threshold (von Frey test; a), withdrawal from noxious heat (Hargreaves test; b), weight-bearing on the CFA-injected hindpaw (c) and the maximum dorsal-ventral thickness of the CFA-injected hindpaw (d) were assessed. All scores are the CFA-injected paw relative to the uninjected paw (right paw score/left paw score × 100), to adjust for individual differences. Each symbol is the mean ± 1 S.E.M. of 10–12 males. CFA, complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Similar to Experiment 1, ketoprofen 3.2 mg/kg alleviated CFA-induced decreases in the mechanical threshold (F1,119 = 50.85, P < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.299) and latency to respond to noxious heat (F1,119 = 66.63, P < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.359), as well as increasing weight-bearing on the CFA-injected paw (F1,119 = 72.10, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.377), and reducing edema (F1,119 = 25.23, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.175) (data not shown). Neither rimonabant nor SR144528 significantly altered ketoprofen effects in either sex, on mechanical allodynia (Antagonist × Ketoprofen: F2,119 = 0.003; no interactions with Sex or Time), heat hyperalgesia (Antagonist × Ketoprofen: F2,119 = 0.637; no interactions with Sex or Time), weight-bearing (Antagonist × Ketoprofen: F2,119 = 0.026; no interactions with Sex or Time), or edema (Antagonist × Ketoprofen: F2,119 = 0.234; no interactions with Sex or Time) (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study shows that three NSAIDs are differentially effective in female and male rats against acute inflammatory pain. The main findings are: (1) NSAIDs are more potent in females than males in reducing pain-related behaviors, whereas anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs tend to favor males; (2) greater ketoprofen-induced antinociception in females, and greater ketoprofen-induced anti-inflammatory effects in males are observed under conditions of acute but not established inflammation; and (3) neither ketoprofen nor celecoxib produce effects that are mediated by cannabinoid receptors in either sex, under the testing conditions used herein.

Sex differences in antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

When administered 2.5 h after induction of pain and inflammation, ibuprofen was more effective in females than males in reducing mechanical allodynia, heat hyperalgesia and biased weight-bearing. These sex differences were significant when 0.5–24 h time course data were analyzed, as well as when AUC values (0.5–6 h) were analyzed, although ibuprofen potency at the peak time of observed effect (3.5 h) was not significantly different in females and males. Similar to ibuprofen, ketoprofen was more effective in females than in males in reducing mechanical allodynia and biased weight-bearing, based on the analysis of both complete time course and AUC data; furthermore, ketoprofen was more potent though not more efficacious in females than in males at the time of peak observed effect, on these two pain-related behaviors. In contrast, sex differences in the antihyperalgesic effects of ketoprofen were minimal, regardless of analysis. Finally, celecoxib was also more effective in females than in males in reducing mechanical allodynia and biased weight-bearing, but primarily at the 24-h time point, as reflected by significant Sex × Time interactions in the complete time course analyses, and a lack of sex differences in the AUC analysis (0.5–6 h) or peak effect analysis (3.5 h). Thus, sex differences in antinociceptive effects of celecoxib were primarily a slightly longer duration of action in females compared to males.

In contrast to the sex differences observed when ketoprofen was administered 2.5 h after CFA, there were no sex differences in the ketoprofen effect when it was administered 3 days after induction of inflammation (Experiment 2). Although our experiments were not designed to directly (statistically) compare ketoprofen effect under conditions of acute vs. established inflammation, the results of Experiments 1 and 2 suggest that greater female sensitivity to NSAID antinociception is related to the acute inflammatory response rather than to later phase inflammatory responses.

In contrast to the greater acute antinociceptive effects of NSAIDs observed in females, all three NSAIDs tended to be more effective in reducing hindpaw inflammation in males. This sex difference was statistically significant for ketoprofen (at early time points, including at the time of peak observed effect) and for celecoxib (all three analyses), whereas ibuprofen was slightly but not significantly more potent in males than in females.

The present finding of greater NSAID antinociception in females agrees with two previous studies in rats demonstrating that a single dose of ibuprofen (Kerins et al., 2003: temporomandibular CFA model) or diclofenac (Romanowska et al., 2008: acute pressure) produced greater or longer-lasting antinociception in female than in male rats. The present finding that two of three NSAIDs had greater anti-inflammatory effects in males compared to females also agrees with a previous study showing greater naproxen (50 mg/kg)-induced reductions in paw edema in male compared to female rats, using a collagen-induced arthritis model (Li et al., 2017); pain-related behaviors were not assessed in that study. Taken together, the present and previous studies demonstrate sex differences in NSAID effects in rodents using several different drugs and various pain tests/models, and suggest that NSAIDs are more potent in reducing pain in females, but more potent (and more efficacious, in some cases) in reducing inflammation in males. In the current study, statistically significant sex differences in acute NSAID effects were associated with small-to-medium effect size estimations (partial η2 values of 0.035–0.19), indicating that sex differences explain little variation in the NSAID effect in some cases, but may be large enough to be functionally important in others.

Mechanisms underlying sex differences in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug effect

Because all NSAIDs are COX inhibitors, it is possible that sex differences in COX expression or activity may underlie sex differences in NSAID effect. Some sex differences in COX have been reported. For example, 4 h after inflammation was induced by intrathoracic carrageenan, COX-2 was significantly higher in male than in female mice in thoracic exudate (Pace et al., 2017). COX-2 expression was also higher in neutrophils from male compared to female humans (Pace et al., 2017), and in brains of male compared to female rats (Günther et al., 2015). Moreover, using a 20-day CFA model of arthritis, Chillingworth et al. (2006) showed that COX-1 or COX-2 gene knockout reduced the development of joint edema and destruction in female but not male mice, whereas the development of mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia were COX-2 gene-dependent in both sexes. Given that ketoprofen is a COX-1-preferring inhibitor, ibuprofen is a nonselective COX-inhibitor, and celecoxib is a COX-2-preferring inhibitor (Cryer and Feldman, 1998; Varrassi et al., 2020), we expected that sex differences in NSAID effect would differ among these drugs. However, sex differences in antinociception (greater in females) and in anti-inflammatory effect (greater in males) were similar among the three NSAIDs, suggesting that sex differences are not related to COX-specificity per se. It should be noted that among COX-2-preferring inhibitors, however, celecoxib is the least selective (Varrassi et al., 2020), so sex differences in celecoxib effect could be due to COX-1 in addition to COX-2 inhibition. In other words, all of the NSAIDs we tested inhibit COX-1 to some extent, so sex differences in the role of COX-1 cannot be ruled out.

An additional mechanism that may contribute to sex differences in NSAID antinociception involves voltage-gated sodium channels. CFA and other inflammatory pain inducers are known to increase voltage-gated sodium channel 1.7 (Nav 1.7) expression in dorsal root ganglia, leading to increased neuronal excitability and thus behavioral hyperalgesia and allodynia (Gould et al., 1998; Tanaka et al., 1998). Ibuprofen and NS398 (a COX-2 selective inhibitor) have been shown to suppress CFA-induced increases in Nav 1.7 expression in rats (sex not specified: Gould et al., 2004). If both COX-1 and −2 inhibitors reduce the expression of Nav 1.7 (and/or other Nav channels known to be involved in inflammatory pain) more in females than in males, all NSAIDs would be more effective antinociceptive agents in females than males. To our knowledge, this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Finally, sex differences in pharmacokinetics of some NSAIDs have been reported in rats (Roskos and Boudinot, 1990), and humans (Lorier et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016; but see Knights et al., 1995), although the direction and type of sex differences may be drug- and species-specific. In the present study, for a given NSAID, sex differences were not consistent across all measures, whereas sex differences that are consistent across measures would be predicted if sex differences were simply due to, say, greater blood levels of the NSAID in one sex compared to the other. Thus, it is unlikely that sex differences in antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of each NSAID are due simply to sex differences in blood levels of that NSAID.

In the present study, estrous stage only significantly modulated females’ response to the anti-inflammatory effect of one NSAID, celecoxib. This study was not explicitly designed to investigate estrous stage modulation of NSAID effects; females were randomly selected for testing without regard to estrous stage. Thus, the distribution of females among estrous stages was not the same across all doses of each drug, and so the only statistical comparison that could be conducted was an analysis of covariance. We have previously observed that in studies designed and powered to detect the estrous stage modulation of opioid (Stoffel et al., 2003) and cannabinoid (Craft and Leitl, 2008; Wakley and Craft, 2011) antinociception, estrous stage can influence analgesic potency. In regard to previous NSAID studies examining the impact of estrous stage, diclofenac antinociception did not differ significantly among female rats in different estrous stages (Romanowska et al., 2008), and ketoprofen pharmacokinetics did not differ among female rats in different estrous stages (Bruguerolle and Bouvenot, 1991). However, another study demonstrated that estradiol could prolong the antinociceptive effect of a COX-2 inhibitor (NS398) while not altering the effects of a COX-1 inhibitor, using a carrageenan model of inflammatory pain (Hunter et al., 2011). Together with our preliminary finding that females in estrus (within 24 h of peak estradiol: Freeman, 1988) were the most sensitive to celecoxib-induced reductions in edema, further investigation into estrous stage and ovarian hormone modulation of the NSAID effect may be warranted, particularly for COX-2 inhibitors.

Cannabinoid receptor mediation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug effects

Several previous studies implicate the endocannabinoid system in the antinociceptive effects of NSAIDs. Intrathecal administration of the nonselective COX inhibitor indomethacin was antinociceptive in wildtype but not CB1R knockout mice, and in wildtype mice, intrathecal administration of a CB1R antagonist blocked indomethacin antinociception (Gühring et al., 2002). In anesthetized rats, intrathecal CB1R blockade also reduced the effect of the COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide on mechanically evoked responses of dorsal horn neurons (Staniaszek et al., 2010), and reversed the effect of another COX-2 inhibitor on the development of inflammation-evoked spinal neuron hyperexcitability (Telleria-Diaz et al., 2010). In the present study, neither CB1R- nor CB2R-selective antagonists given i.p. significantly decreased the effects of celecoxib or ketoprofen on pain-related behaviors or on inflammation, in either sex. Our negative finding agrees with a previous study in which neither rimonabant nor SR144528 given i.p. attenuated the antinociceptive effects of oral indomethacin in male mice (Anikwue et al., 2002). Additionally, peripheral antinociceptive effects of intraplantar dipyrone, indomethacin, and diclofenac (the latter being highly COX-2-selective) were not blocked by intraplantar CB1R or CB2R antagonists in rats (Silva et al., 2012). Taken together, the present and previous studies on the cannabinoid receptor mediation of NSAID antinociception suggest that endocannabinoid involvement in the effects of NSAIDs may be limited to spinal nociceptive processes. Thus, cannabinoid involvement may be less likely to be observed when NSAIDs are administered systemically and their actions involve multiple levels of the pain neuraxis. However, it is also possible that the relatively short duration of action of rimonabant compared to the NSAIDs tested in our study contributed to the lack of antagonism we observed: maximal NSAID effects were observed 1.5–3.5 h postinjection, a time at which rimonabant effects are waning (Järbe et al., 2010).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that female rats are more sensitive than males to the antinociceptive effects of NSAIDs that vary in COX-selectivity, when NSAIDs are administered soon after the induction of inflammatory pain. In contrast, two of three NSAIDs were more effective in reducing hindpaw inflammation in males than in females. It is not yet clear whether sex differences observed in animal studies translate to humans, as no systematic dose- and time-effect analyses of NSAID analgesia or anti-inflammatory effect have been conducted in women vs men. As noted in a 2009 review of clinical trials on the COX-2 inhibitor etoricoxib, women were underrepresented in Phase I trials, and although there were many women in Phase II trials, almost none of the 58 published trials reviewed included sex comparisons of etoricoxib efficacy and side-effects (Chilet-Rosell et al., 2009). The present results underscore the importance of conducting sex difference analyses, to determine whether there is any basis for refining prescribing guidelines for NSAIDs in women vs men.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Psychopharmacology Research Fund and a Herbert L. Eastlick Professorship (to R.C.), and by National Institute on Drug Abuse T32 DA035200 (to S.B.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anikwue R, Huffman JW, Martin ZL, Welch SP (2002). Decrease in efficacy and potency of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by chronic delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303:340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbuch M, Katzper M (2000). A search for sex differences in response to analgesia. Arch Intern Med 160:3424–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruguerolle B, Bouvenot G (1991). Lack of evidence of ketoprofen kinetic changes during the oestrous cycle in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 5:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilet-Rosell E, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Horga JF (2009). Women’s health and gender-based clinical trials on etoricoxib: methodological gender bias. J Public Health (Oxf) 31:434–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chillingworth NL, Morham SG, Donaldson LF (2006). Sex differences in inflammation and inflammatory pain in cyclooxygenase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291:R327–R334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton P, Charuvastra VC, Ling W (2003). Effect of oral ketorolac and gender on human cold pressor pain tolerance. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 30:759–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, Craft RM (2018). Sex-dependent effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: a translational perspective. Neuropsychopharmacology 43:34–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Kandasamy R, Davis SM (2013). Sex differences in anti-allodynic, anti-hyperalgesic and anti-edema effects of Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat. Pain 154:1709–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Leitl MD (2008). Gonadal hormone modulation of the behavioral effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in male and female rats. Eur J Pharmacol 578:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryer B, Feldman M (1998). Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity of widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med 104:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME (1988). The neuroendocrine control of the ovarian cycle of the rat. In: The Physiology of Reproduction. Knobil E, Neill J, editors. New York: Raven Press; pp. 1893–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Gould HJ III, England JD, Liu ZP, Levinson SR (1998). Rapid sodium channel augmentation in response to inflammation induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant. Brain Res 802:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould HJ III, England JD, Soignier RD, Nolan P, Minor LD, Liu ZP, et al. (2004). Ibuprofen blocks changes in Na v 1.7 and 1.8 sodium channels associated with complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced inflammation in rat. J Pain 5:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gühring H, Hamza M, Sergejeva M, Ates M, Kotalla CE, Ledent C, Brune K (2002). A role for endocannabinoids in indomethacin-induced spinal antinociception. Eur J Pharmacol 454:153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther M, Plantman S, Davidsson J, Angéria M, Mathiesen T, Risling M (2015). COX-2 regulation and TUNEL-positive cell death differ between genders in the secondary inflammatory response following experimental penetrating focal brain injury in rats. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 157:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, McLachlan AJ, Day RO, Davies RA (2009). Can predictors of response to NSAIDs be identified in patients with acute low back pain? Clin J Pain 25:659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DA, Barr GA, Shivers KY, Amador N, Jenab S, Inturrisi C, Quinones-Jenab V (2011). Interactions of estradiol and NSAIDS on carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia. Brain Res 1382:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TU, Gifford RS, Makriyannis A (2010). Antagonism of Δ9-THC induced behavioral effects by rimonabant: time course studies in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 648:133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerins CA, Carlson DS, McIntosh JE, Bellinger LL (2003). Meal pattern changes associated with temporomandibular joint inflammation/pain in rats; analgesic effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knights KM, McLean CF, Tonkin AL, Miners JO (1995). Lack of effect of gender and oral contraceptive steroids on the pharmacokinetics of ®-ibuprofen in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol 40:153–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, DuBois DC, Song D, Almon RR, Jusko WJ, Chen X (2017). Modeling combined immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects of dexamethasone and naproxen in rats predicts the steroid-sparing potential of naproxen. Drug Metab Dispos 45:834–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorier M, Magallanes L, Ibarra M, Guevara N, Vázquez M, Fagiolino P (2016). Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of ketoprofen after oral administration of modified-release formulations in Caucasian healthy subjects. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 41:787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirandola L, Wade R, Verma R, Pena C, Hosiriluck N, Figueroa JA, et al. (2015). Sex-driven differences in immunological responses: challenges and opportunities for the immunotherapies of the third millennium. Int Rev Immunol 34:134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RA, Straube S, Paine J, Derry S, McQuay HJ (2011). Minimum efficacy criteria for comparisons between treatments using individual patient meta-analysis of acute pain trials: examples of etoricoxib, paracetamol, ibuprofen, and ibuprofen/paracetamol combinations after third molar extraction. Pain 152:982–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pace S, Rossi A, Krauth V, Dehm F, Troisi F, Bilancia R, et al. (2017). Sex differences in prostaglandin biosynthesis in neutrophils during acute inflammation. Sci Rep 7:3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowska K, Grotkiewicz M, Rewekant M, Makulska-Nowak HE (2008). Sex dependent antinociceptive activity and blood pressure changes in SHR, WKY and WAG rat strains after diclofenac treatment. Acta Pol Pharm 65:723–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskos LK, Boudinot FD (1990). Effects of dose and sex on the pharmacokinetics of piroxicam in the rat. Biopharm Drug Dispos 11:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JL, Jureidini B, Hodges JS, Baisden M, Swift JQ, Bowles WR (2008). Gender differences in analgesia for endodontic pain. J Endod 34:552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Nan F, Li M, Liang M, Wang Y, Chen Z, Luo Z (2016). Pharmacokinetic properties of intravenous ibuprofen in healthy Chinese volunteers. Clin Drug Investig 36:1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LC, Romero TR, Guzzo LS, Duarte ID (2012). Participation of cannabinoid receptors in peripheral nociception induced by some NSAIDs. Braz J Med Biol Res 45:1240–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniaszek LE, Norris LM, Kendall DA, Barrett DA, Chapman V (2010). Effects of COX-2 inhibition on spinal nociception: the role of endocannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol 160:669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel EC, Ulibarri CM, Craft RM (2003). Gonadal steroid hormone modulation of nociception, morphine antinociception and reproductive indices in male and female rats. Pain 103:285–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sycha T, Gustorff B, Lehr S, Tanew A, Eichler HG, Schmetterer L (2003). A simple pain model for the evaluation of analgesic effects of NSAIDs in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56:165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Cummins TR, Ishikawa K, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Waxman SG (1998). SNS Na+ channel expression increases in dorsal root ganglion neurons in the carrageenan inflammatory pain model. Neuroreport 9:967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telleria-Diaz A, Schmidt M, Kreusch S, Neubert AK, Schache F, Vazquez E, et al. (2010). Spinal antinociceptive effects of cyclooxygenase inhibition during inflammation: Involvement of prostaglandins and endocannabinoids. Pain 148:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varrassi G, Pergolizzi JV, Dowling P, Paladini A (2020). Ibuprofen safety at the golden anniversary: are all NSAIDs the same? A narrative review. Adv Ther 37:61–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakley AA, Craft RM (2011). Antinociception and sedation following intracerebroventricular administration of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in female vs. male rats. Behav Brain Res 216:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JS, Carmody JJ (1998). Experimental pain in healthy human subjects: gender differences in nociception and in response to ibuprofen. Anesth Analg 86:1257–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Boudreau DM, Freedman AN (2014). Trends in the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general U.S. population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 23:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]