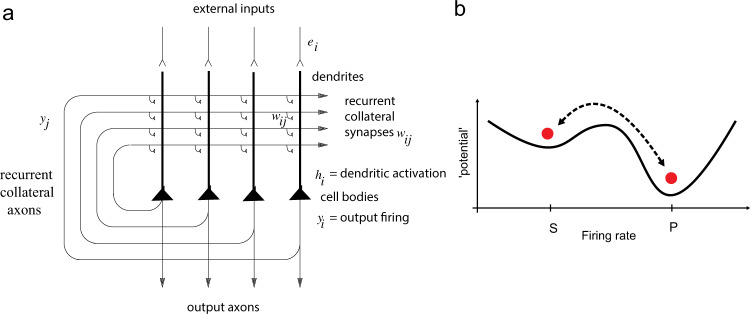

Fig. 1. Attractor Networks.

a Architecture of an attractor network. External inputs ei activate the neurons in the network, and produce firing yi, where i refers to the i’th neuron. The neurons are connected by recurrent collateral synapses wij, where j refers to the jth synapse on a neuron. By these synapses, an input pattern on ei is associated with itself, and thus the network is referred to as an autoassociation network. Because there is positive feedback via the recurrent collateral connections, the network can sustain persistent firing. These synaptic connections are assumed to be formed by an associative (Hebbian) learning mechanism. The inhibitory interneurons are not shown. They receive inputs from the pyramidal cells and make negative feedback connections onto the pyramidal cells to control their activity. The recall state (which could be used to implement short-term memory or memory recall) in an attractor network can be thought of as the local minimum in an energy landscape. b Energy landscape. The first basin (from the left) in the energy landscape is the spontaneous state with a low firing rate (S), and the second basin is the high firing rate attractor state, which is ‘persistent’ (P) in that the neurons that implement it continue firing at a high rate. The vertical axis of the landscape is the energy potential. The horizontal axis is the firing rate, with high to the right. In the normal condition, the valleys for both the spontaneous and for the high firing attractor state are equally deep, making both states stable. In general, there will be many different high firing rate attractor basins, each corresponding to a different memory. In schizophrenia, it is hypothesized that the high firing rate (P) state is too shallow due to low firing rates, providing instability which leads to the cognitive symptoms of poor short-term memory and attention in the prefrontal cortex. It is also hypothesized that in schizophrenia the spontaneous firing rate state (S) is too shallow due to reduced inhibition and that this leads to noise-induced jumping into high-firing rate states in the temporal lobe that relate to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia such as hallucinations and delusions. In contrast, it is hypothesized that in obsessive–compulsive disorder, the basin for the high firing attractor state is deep, making the high firing rate attractor state that implements for example short-term memory too stable, and very resistant to distraction29. This increased depth of the basin of attraction of the persistent state may be associated with higher firing rates of the neurons if for example the state is produced by increased currents in NMDA receptors29.