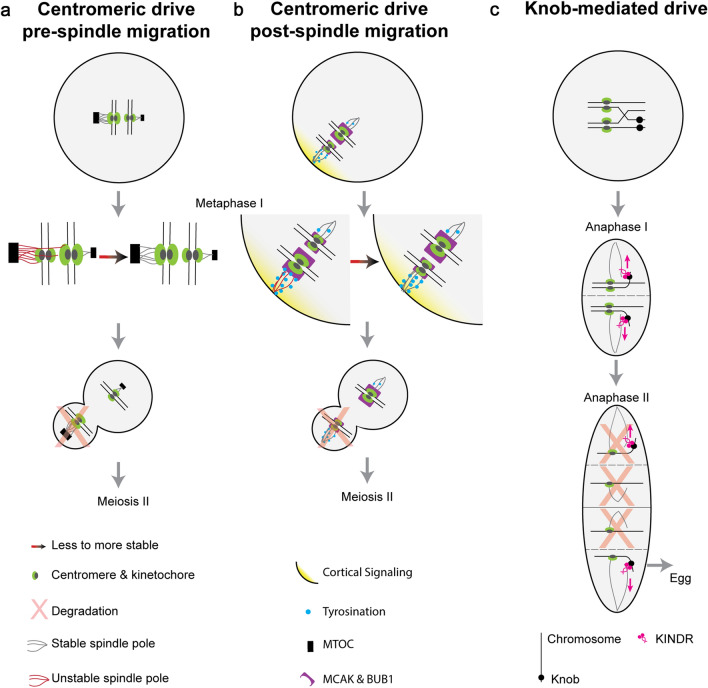

Fig. 2.

Models of Asymmetric Meiotic Drive. This figure depicts the mechanistic understanding of two examples of centromeric drive (a and b) and one example of non-centromeric drive (c). a An example of female centromeric drive in hybrid mice where cis-acting chromosome reorientation occurs before trans-acting spindle migration. In this system, larger MTOCs (black box) give rise to denser spindle poles (gray line) which preferentially interact with larger kinetochores (green oval). If this favorable interaction is not initially established (red line), then proteins involved in fixing erroneous microtubule attachments are recruited and chromosomes reorient to the more favorable interaction (red–black arrow). Spindles migrate to the periphery, and the outward-facing larger kinetochore is extruded to the polar body and degraded (red X). b Another example of female centromeric drive in hybrid mice where chromosomes reorientation occurs after spindle migration. Cortical signaling (yellow gradient) leads to an enrichment of tyrosination (blue circle) on cortical spindle poles. Spindle pole tyrosination is less stable (red lines) on larger kinetochores (green) with more BUB1 kinase and MCAK (purple). If not in the more stable orientation, then proteins involved in fixing erroneous microtubule attachments cause chromosomes to reorient to the stable orientation (red–black arrow), causing the smaller kinetochore to be extruded to the polar body (red X). c Maize knob-mediated drive requires the kinesin KINDR (pink) which binds knob repeats (black circles) and migrates along the spindle microtubules toward the outward spindle poles (pink arrow), including the distal cell which becomes the egg