Abstract

The present work includes a numerical study of natural convection heat transfer in symmetrical and unsymmetrical corrugated annuli filled with H2O-Al2O3 nanofluid. In this study, higher and lower temperatures were kept constant at inner and outer cylinders of the annulus; respectively. Eight mathematical models with an aspect ratio of 1.5 were developed to find the best model giving the highest heat transfer rates. The stream-vorticity formulation in curvilinear coordinates was used to solve the governing equations of heat transfer and fluid motion. The influences of Rayleigh number. Ra and volume fraction of nanoparticles. ( on isotherms, streamlines, local and average Nusselt numbers on the inner and outer cylinder were investigated. The results show that the heat transfer rate is significantly increased with an increase in nanoparticles volume fraction and Rayleigh number. The activity of the heated surface is increased with an increase in the undulation number, but the flow motion tends to be most difficult in the spaces between active undulation walls. Moreover, the heat transfer rates in unsymmetrical annuli are relatively higher than the rates in the symmetrical annuli. There are no evident changes in isotherms with an increase in the nanofluid volume fraction. Correlations for the mean Nusselt number on the inner and outer walls of annulus were deduced as a function of Rayleigh number and nanoparticles volume fraction for eight models with an accuracy range of 8–15 %.

Keywords: Energy, Mechanical engineering, Nanotechnology, Thermodynamics, Computational heat transfer, Energy storage technology, Heat transfer, Natural convection, Nanofluids, Nanoparticles, Annular cavity, Enclosure, Corrugated annulus

Energy; Mechanical engineering; Nanotechnology; Thermodynamics; Computational heat transfer; Energy storage technology; Heat transfer; Natural convection, Nanofluids, Nanoparticles, Annular cavity, Enclosure, Corrugated annulus.

1. Introduction

Natural convective heat transfer characteristics in enclosures have a great significance in industrial applications such as solar collectors, thermal storage systems, cooling of nuclear reactors, etc. In past years, different methods were used to augment the heat transfer in enclosures such as using porous media [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] and nanotechnology [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. The corrugated annulus is a type of enhanced heat transfer techniques. Corrugation aims to raise the secondary currents by producing radial velocity components and high flow mixing. As a result, the increase in the wet perimeter with remaining the cross-section area constant leads to an increase in the convective surface area. Therefore, it was extensively used in modern heat exchangers applicated in steam generation, condensation in power and cogeneration plants, chemical and agricultural products, automobile industry, etc. [44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58].

Hasanuzzamana et al. 2007 [44], studied the natural convection in a square cavity having two V-wavy parallel vertical plates and two flat horizontal plates. It was noticed that the average Nusselt number increased with the increase in the input heat energy. Noman et al. 2008 [45], concluded that the natural convection phenomena in a square enclosure with a hot sinusoidal corrugated top surface are affected by changing the inclination angles. Hasan et al. (2012) [46], noticed that the transient phenomena of natural convection in a square enclosure are affected by Rayleigh Number, corrugation amplitude, and frequency. Salam et al. 2013 [47], studied the inclination effect of hot thin plate located concentrically in an enclosure on the behavior of thermal field and fluid flow. The results showed that the heat transfer rate increased with increase in the corrugation frequency and the inclination angle of plate. Souad and Amina 2015 [48], found that the heat transfer rate in a square cavity decreased, and the total entropy generation raised with the increase in Bijan number and the amplitude of the hot wavy right wall. Chordiya and Sharma 2019 [49], studied the effect of shape, position, amplitude, and inclination angle of corrugated diathermal partitions in a porous cavity on the thermal distribution and fluid flow. They concluded that, for higher Rayleigh numbers, the existence of corrugated partitions led to the increase in heat transfer rate by about 61%. Behrouz and Saeed 2015 [50], employed H2O, Al2O3-H2O nanofluid, and Al2O3-Cu-H2O hybrid nanofluid to examine the natural convection heat transfer in a cavity having sinusoidal corrugated vertical walls. It was observed that the enhancement of heat transfer increased at higher Rayleigh numbers and volume concentrations. Saha 2017 [51], used H2O-TiO2 nanofluid to enhance the heat transfer inside a cavity with vertical sinusoidal walls and adiabatic horizontal flat walls. The results revealed that the heat transfer rate using TiO2 nanofluid was higher compared with using base fluid only. Mitchell 2017 [52], analyzed the heat transfer by natural convection inside a wavy enclosure containing Al2O3-water nanofluid. They concluded that the heat transfer rate increased with the increase in surface waviness, aspect ratio, and nanoparticles volume fraction. Soroush et al. 2017 [53], studied the turbulent free convection, conduction, and surface thermal radiation in a rectangular cavity with different shapes of heat source located at the bottom wall. It was noticed that employing the circular obstacles for heat source gave a higher heat transfer rate than other shapes only in low emissivity values. Walid 2018 [54], analyzed the heat transfer and fluid flow in a three-dimensional triangular solar collector with a hot corrugated bottom wall. It was noticed that the flow strength and the heat transfer rate at the heated surface increased with the increase in Rayleigh number. Ammar et al. 2019) [55], used various undulation numbers of a hot cylinder located inside a cooled wavy-walled enclosure filled with Ag nanofluid layer on the right half and a fully saturated porous media with Ag nanofluid on the left half. It was found that the average Nusselt number decreased with increase in the thickness of the porous layer. Rujda and Mahapatra 2019 [56], studied the effect of magnetic field on the natural convection and mass transfer in a wavy-walled cavity filled with water-based Al2O3 nanofluid. It was observed that increasing the undulations number and buoyancy ratio led to reducing the performance of heat and mass transfer rate. Dutta et al. 2020 [57], studied the natural convection in a porous corrugated rhombic cavity. It was noticed that the heat transfer process was indicated by the interaction between Rayleigh number and Darcy number together with a number of undulations. Abeer 2020 [58], enhanced the natural convection inside a square porous cavity by 10% with an increase in nanoparticle concentration. It was concluded that the average Nusselt number of the corrugated cylinder was slightly better than the Nusselt number for the smooth cylinder at the same conditions.

However, despite the significance of corrugation in different industrial applications, few investigations were concerned with corrugation utilization in a heat transfer augmentation study. Therefore, the present work comprises a numerical analysis of natural convection heat transfer in corrugated annuli filled with Al2O3 nanofluid. Eight mathematical models have been developed to find the best model giving the highest heat transfer rates. The ranges of Rayleigh number and volume fraction of nanoparticles were Ra and ; respectively.

2. Mathematical modeling

2.1. Physical domain

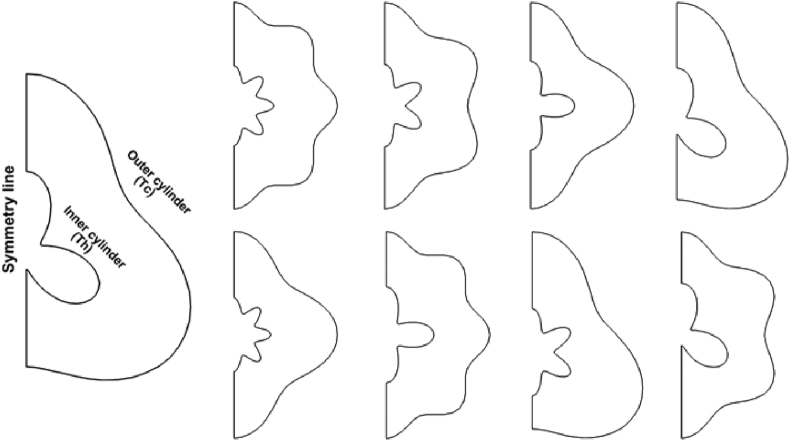

In the present work, eight models of two-dimensional corrugated annuli with radius ratio = 2.66, and filled with Al2O3-H2O nanofluid are studied as can be shown in Figure 1. The inner hot cylinder and the outer cold cylinder of annuli are maintained at and ; respectively. The characteristic length is taken as . The following mathematical functions are applied to have the corrugation walls of annuli [37].For symmetry simulation, changed from to

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where,

Figure 1.

Geometry configurations for eight models.

at inner cylinder

at outer cylinder number of undulations

amplitude.

= azimuth angle (deg)

2.2. Governing equations and formulation

As previously mentioned, the gap between the inner and outer cylinders of the annulus is filled with Al2O3-H2O nanofluid having ten values of volume fraction extended from 0 to 0.25. The thermophysical properties of the nanofluid are given in Table 1 [59]:

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties of water and nanoparticles [59].

| Material | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 4179 | 997 | 0.613 | |

| 765 | 3970 | 40 |

The thermophysical properties of H2O-Al2O3 nanofluid at different volume fractions must be estimated. These properties include the density , thermal expansion coefficient. and specific heat energy. , thermal conductivity , and dynamic viscosity , which are given as follows [59]:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Maxwell-Garanetts and Brinkman models were used in the present work to find the thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of H2O-Al2O3 nanofluid; respectively [50, 60, 61, 62, 63]. A steady-state single-phase incompressible flow and heat transfer by natural convection inside an annulus filled with nanofluid is considered in the present work. Additionally, the two-dimensional continuity, momentum, and energy equations are given below [35, 64]:

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

The stream function and vorticity can be defined as follows:

| (12) |

Variables Definitions’ in the dimensionless form are given below:

,

By substituting the dimensionless variables in Eqs. (8), (9), (10), and (11) and using Eq. (12), the governing equations in streamline-vorticity form become as given below [35, 64]:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

The boundary conditions are:

-

•

, at

-

•

, at ,

-

•

at .

| (16) |

| (17) |

The local and average Nusselt numbers for the inner hot cylinder and outer cold cylinder are given in the following equations:

| (18) |

| (19) |

Where, is the normal direction to the wall, and is the wall length.

The major advantages of applied scheme (stream-vorticity formulation) in two-dimensional natural convection heat transfer and incompressible flow are:

-

•

continuity equation is automatically satisfied

-

•

one vorticity equation will be solved only

-

•

the streamlines of the flow are given by contour lines of the stream function.

-

•

the vorticity is a conserved quantity.

The major scheme limitation is difficulty in extending this formulation to 3D and also due to some difficulties in the vorticity boundary treatment.

2.3. Grid generation

Grid Generation is conclusive for saving of time and cost, and to obtain good results quality for all cases studied in the present work. So, the physical domain should be transformed into a computational domain. The most applicable, programmable, and usage method is the elliptical partial differential equations method which produces grids with quietly changing cell size and slope of the grid lines. Moreover, the Poisson equation is used to control the orthogonality and the required spacing close to the boundaries of the generating system. The transformation functions are defined as

| (20) |

| (21) |

where & are arbitrary functions required to modify the local density of the grids.

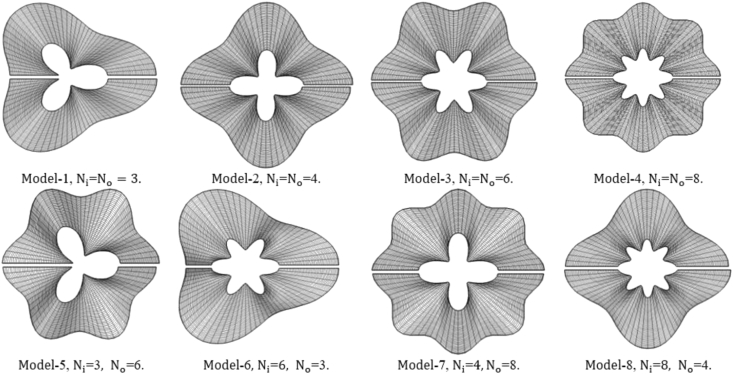

FORTRAN code has been developed to solve the governing equations by iterative scheme named finite difference discretization. In the first step, initial grids in the interior domain are generated using a simple algebraic grid generation method. Then, the solution and iteration process are starting with the initial grid. The final grid does not depend on the initial grid. Finally, the Poisson equations are solved iteratively using the iteration method. The boundary grid points are defined as Dirichlet boundary conditions. Generally, a converged grid is sufficiently obtained after more than 100 iterations. The final grid generation shapes for eight models obtained from FORTRAN code are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Grid used in the present study for eight models of corrugated annuli.

Then, the set of Eqs. (13), (14), and (15) are written in transformation form as given below [65]:

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

Where

, , , , ,

, ,

The dimensionless boundary conditions are given as follows:

-

•

at ,

-

•

at ,

-

•

at ,

-

•

, at .

| (25) |

| (26) |

Eqs. (25) and (26) were calculated using Simpson's rule 1/3 method.

2.4. Selection of grids and validation

To obtain grid-independence, some runs are carried out to make sure the present results are disposed of the mesh calibration, as shown in Table 2. The results included the average Nusselt number on the inner hot cylinder , and maximum/minimum stream functions ,. It is noticed that the grid size of 41 41 is soft enough to achieve accurate results. So, it was adopted.

Table 2.

Grid independency test at = 106, = 0.1.

| Model | Grids |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | 5.202 | 5.504 | 5.604 | 5.604 | ||||

| 2 | 5.207 | 5.400 | 5.527 | 5.527 | ||||

| 3 | 5.098 | 5.175 | 5.200 | 5.200 | ||||

| 4 | 4.977 | 5.149 | 5.271 | 5.271 | ||||

| 5 | 5.276 | 6.034 | 6.154 | 6.154 | ||||

| 6 | 5.254 | 6.006 | 6.177 | 6.177 | ||||

| 7 | 7.165 | 6.472 | 6.105 | 6.105 | ||||

| 8 | 6.987 | 6.353 | 6.163 | 6.163 | ||||

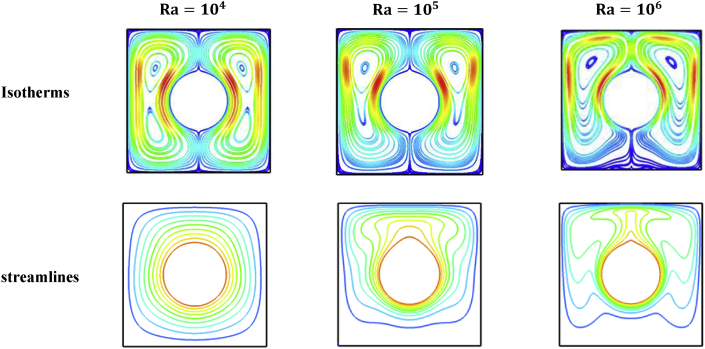

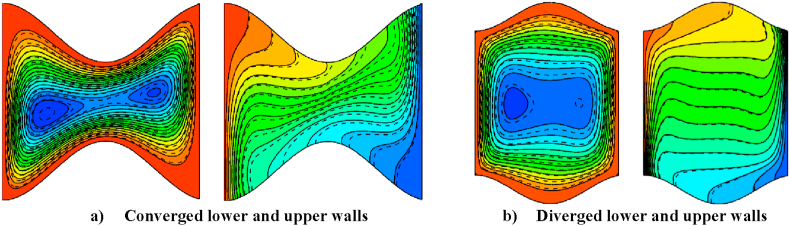

CFD code written in the FORTRAN was used to solve numerically the governing equations. The present numerical results are compared with the results obtained by kim et al. [66] and Moukalled [67] for circular hot cylinder enclosed by a square cylinder filled with air as shown in Table 3. It is noticed that the average Nusselt numbers at a certain Rayleigh number for all works are identified with a small difference ranging from 0.2 % to 1.7 %. Moreover, the results of streamlines and isotherms for the present code according to case study of Kim et al. [66] for Pr = 0.7 are shown in Figure 3. It is noticed that the present results have given a good agreement with the results of kim et al. [66]. Additional validation shown in Figure 4 is carried out by comparison the present results with the published work of Eiyad and Hakan [68] which is the natural convection in two wavy enclosures filled with Al2O3–H2O nanofluid at Ra = 105 and = 0.01. The figure shows that the patterns of streamlines and isotherms for present work are identical to results obtained by [68]. The values of minimum stream function for both works shown in Table 4 are close together with a very little difference ranging from 0.58 % to 4.2 %. As a result of these comparisons, it is concluded that the present numerical analysis is reliable and efficient.

Table 3.

Code validation.

Figure 3.

Streamlines and isotherms in a square enclosure for present numerical results according to case study of [66], Pr = 0.7.

Figure 4.

Streamlines and isotherms in an enclosure with different geometry configurations for present numerical results according to case study of [68] for Ra = 105, water-Al2O3 nanofluid with = 0.1 (a) AR = 0.85, (b) AR = 1.1.

Table 4.

Comparison of present workstream function with Eiyad and Hakan work [68].

| Case |

[68] |

|

Error % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | a | b | a | b | |

| -0.034 | -0.0058 | |||||

| -0.042 | 0.011 | |||||

2.5. Numerical solution

The governing equations associated with boundary conditions were solved numerically by the finite difference schemes. Central difference and forward and backward upwind difference approximations were utilized for partial differential derivatives and convective terms; respectively. While the explicit method was used for velocity and temperature fields. The stream function calculations were performed by using the successive over-relaxation (SOR) method with tolerance 10−6.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Streamlines and isotherms

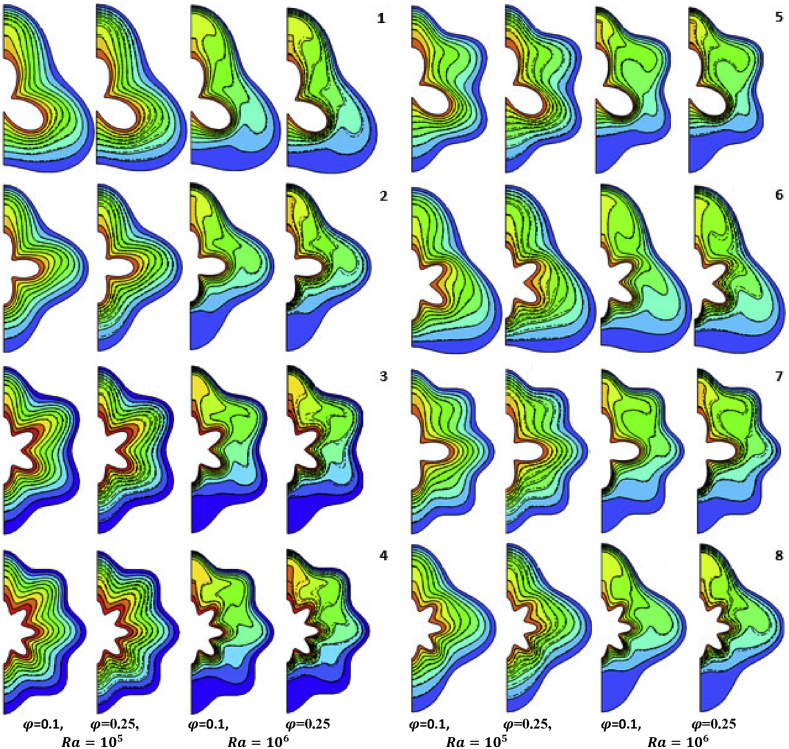

Figures 5 and 6 show the influences of Rayleigh number and the nanoparticles volume fraction on the streamlines and isotherms; respectively, for eight models of annuli. In general, increasing of nanoparticles volume fraction causes an increase in the intensity of streamlines. The lines of flow and temperature are symmetric about the mid vertical line of annulus, so it can be taken one half of the annulus only. Heating the corrugated inner wall leads to movement of the nanofluid in the enclosure. In model one symmetric annulus) at Ra = 104, the streamlines create pair of rotating cells bounded the hot corrugated wall on each half of the annular gap, one is located on the upper undulation of the heated wall, while the other one is located close to the lower undulation of the inner cylinder. The lower and upper cells emerge together with the increase in Rayleigh number. When the cells circulated clockwise, the maximum strength of the streamlines is adopted by . The left cells have a positive stream functions, while the right cells have negative stream function. The hot fluid is displaced upward towards the hot wall. Then it moves downward near to the outer cylinder wall. This leads to generating two-fluid flow directions, clockwise on the right side, and counterclockwise on the left side. On the other side, addition of nanoparticles to the base fluid causes an increase in the thermal conductivity of nanofluid. Increasing the volume fraction of nanoparticles leads to increasing the stream function intensity. So, the streamlines become strong. While, the isotherms seem to be more smoothing as the nanoparticles volume fraction increases. Actually, the existence of nanoparticles (Al2O3) has given an accumulation of the isotherms near the hot wall. This causes improving the heat transfer rates which is expressed by the increase in the Nusselt number. The figure shows also that the behavior of temperature and fluid fields changes with changing of undulation number for inner and outer cylinders (). The activity of heated surface increases by increasing the undulations number, but the flow motion tends to be most difficult in the spaces between active undulation walls. Moreover, there are no vortices at the lower region of the enclosure in which the flow is inert and stably stratified. It is noticed that the strength of the flow movement is decreased with the increase in corrugation number. Additionally, the streamlines cells extend toward upward because the reduction in the hot area causes changing the pattern of vortices. The multiple cellular motions are still continual at model two (, symmetric annulus), with weaker flow circulation than model one ). In this model, three major vortices are found on each side of the enclosure, located close to the upper, side, and lower undulations; respectively. These vortices tend to emerge together with the increase in Rayleigh number. The intensity of vorticity (stream function) increases with the increase in number of undulations for inner and outer cylinders to six as shown in model-3 ). In this model, three cells on each side have generated at the top, middle, and bottom of the annulus. In each half of model-4 ), one major vortex is found in the middle of the annulus. It moves towards the top of the annulus as the Rayleigh number is increased.

Figure 5.

Streamlines for eight models of corrugated annuli at nanoparticle volume fractions .

Figure 6.

Isotherms for eight models of corrugated annuli at nanoparticle volume fractions .

At a small Rayleigh number, the temperature distribution seems to appear with a shape similar to the shape of the corrugated inner cylinder because of weak fluid flow. At high Rayleigh numbers, the hot corrugated cylinder tends to transmit the heat to the nanofluid because of its highest temperature compared to temperature of the nanofluid inside the annular gap. The streamlines cells nearby the left and right surfaces begin to extend horizontally. Moreover, the streamlines move vertically far from the lower portion of the enclosure. The isotherms pattern distorts and the flow is almost not impacted adjacent to the bottom wall. Increasing Rayleigh number means fast flow circulation and thicker thermal boundary layer in the upper region. This leads to moving the isotherms pattern vertically, which means increasing the thermal currents at the upper part of the annulus. At a high Rayleigh number (Ra = 106), the thermal currents are powerful enough to push heat toward the left and right corrugated walls. Generally, the patterns of isothermals for the symmetrical models (1–4) are nearly similar. The isotherms extend horizontally due to the flow strongly impacts the top cold wall boundary.

One main major vortex located in the first quarter of annulus is found in model-5 (). Additionally, minor vortex generates down the lower part of the enclosure and emerges with the main vortex as Rayleigh number increases. In this model, the large active volume causes increasing the temperature gradient in the upper portion of the enclosure. The strength of the fluid circulation enlarges the significantly. Two major vortices are generated in model-6 ). The first one is located at the upper part of the annulus, while the other is located on the bottom side. They emerge together with the increase in Rayleigh number. In model-7 ), the mini vortex is penetrated in the middle horizontal line of the annulus, while two major vortices are generated above and below the middle horizontal line of annulus on each side of the enclosure. These cells tend to reverse their nature if the number of undulations is reversed between the inner and outer cylinders as shown in model-8 ). It is noticed that the major vortex permeates the horizontal axis of the enclosure and the other two minor vortices are generated above and below the horizontal axis of the annulus. The major-minor vortices emerge together with the increase in Rayleigh number. Increasing the corrugation number enlarges the hot surface area and increasing the temperature gradient. As a result, the flow is accelerated. The intensity of stream function increases significantly with the increase in the Rayleigh number. This means that the buoyancy force increases and overcomes the viscous force. As a result, the natural convection is the dominating factor in the heat transfer process. The conduction heat transfer is dominated at low Rayleigh number. In this case, the isotherms arrange in paths parallel to the shape of annulus walls. The behavior of thermal fields changes with increase in Rayleigh number to 106. The dominating convective heat transfer makes the isotherms to be undulant. There are no significant changes in isotherms contour with the changing of nanoparticles volume fraction.

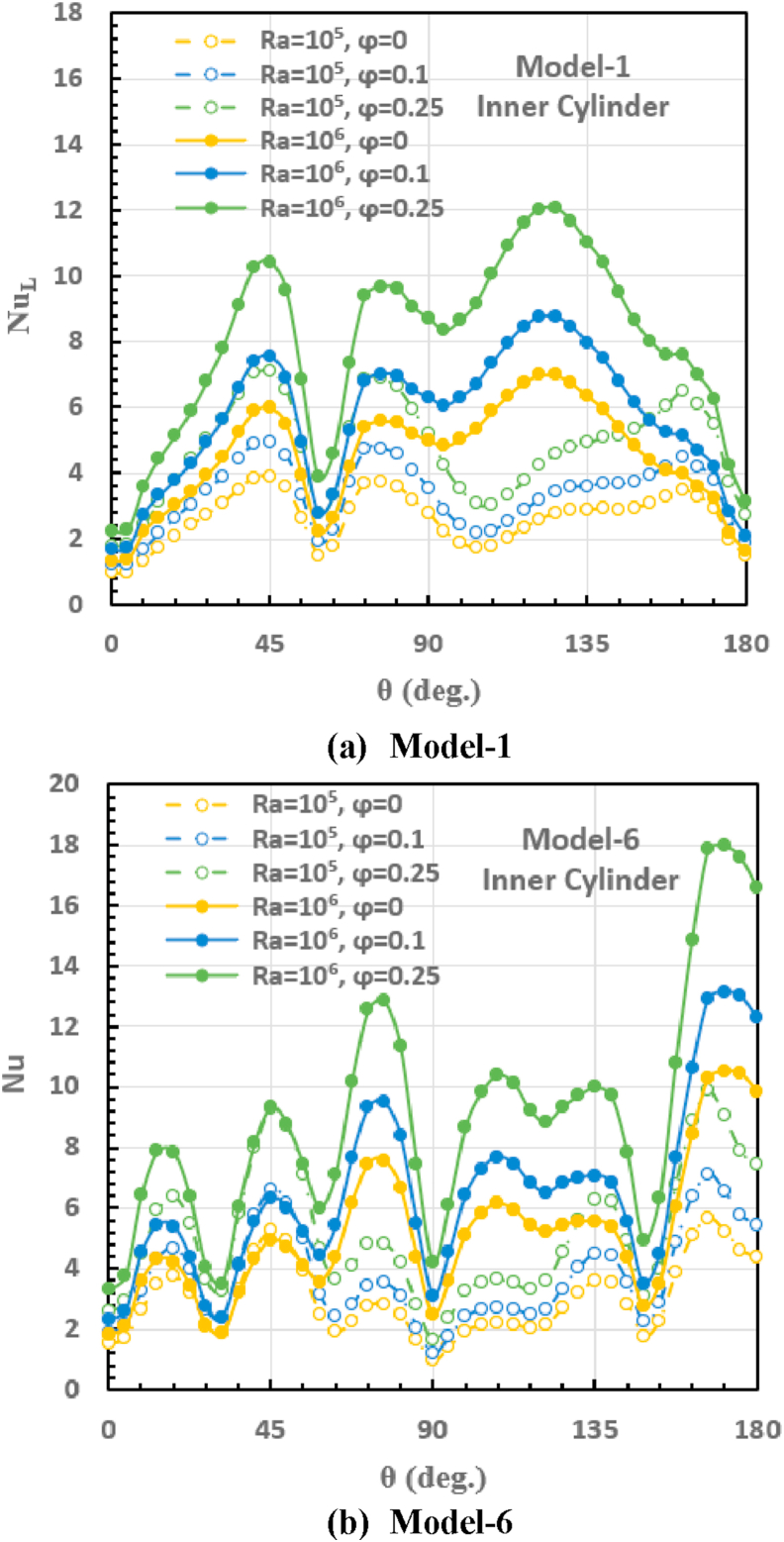

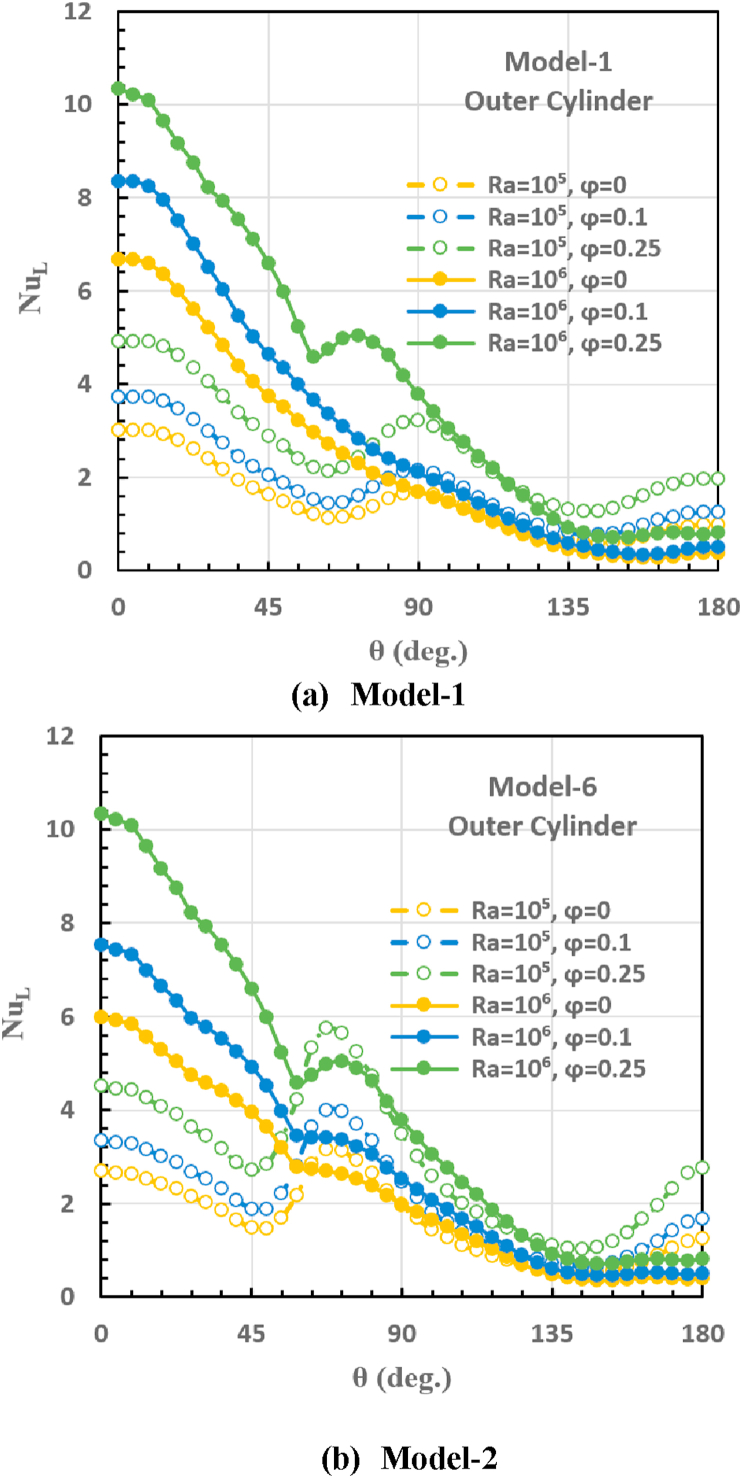

3.2. Local Nusselt number

Figures 7 and 8 show the local Nusselt number variation around the inner outer cylinders from = (top of wall) to (bottom of wall) for model 1 and model 6; respectively, at two Rayleigh numbers (Ra = and and three-volume fractions (). As can be shown in Figure 7 that the number of peaks for Nusselt number is similar to the number of undulations. The maximum Nusselt numbers on the inner cylinder after which the curve begins to descend are located at for model one, and at ( for model six. While, the minimum values after which the curve begins to rise are located at ( for model one, and at ( for model six, as shown in Figure 7. As we have said previously, the activity of heated surface increases by increasing the number of undulations. But, the flow motion tends to be most difficult in the space between active undulation walls. So, these regions are almost sluggish leading to reduction in the heat transfer rate. Moreover, the heat transfer rate decreases at the top and bottom of the inner cylinder. Additionally, the maximum and minimum Nusselt numbers on the outer cylinder are located at the top region ( and close to the bottom region (nearly at ; respectively, as shown in Figure 8. Generally, increasing the local Nusselt number with Rayleigh number and nanoparticle volume fraction is related to increase vortex intensity and the heat transfer activity between the nanoparticles and water. Furthermore, increasing the thermal conductivity of the nanofluid gives more heat transport to the cold wall compared with the hot wall. Additionally, the induced buoyancy force raises the hot fluid towards the inner hot wall while the colder fluid is displaced downward towards the outer cold wall. More importantly, the heat transfer behavior along the outer cylinder is slightly affected by increasing the number of undulations for the inner hot cylinder which causes increasing the heat transfer rate on the inner cylinder.

Figure 7.

Local Nusselt number for the inner cylinder at different Rayleigh numbers and nanoparticle volume fractions.

Figure 8.

Local Nusselt number for the outer cylinder at different Rayleigh numbers and nanoparticles volume fractions.

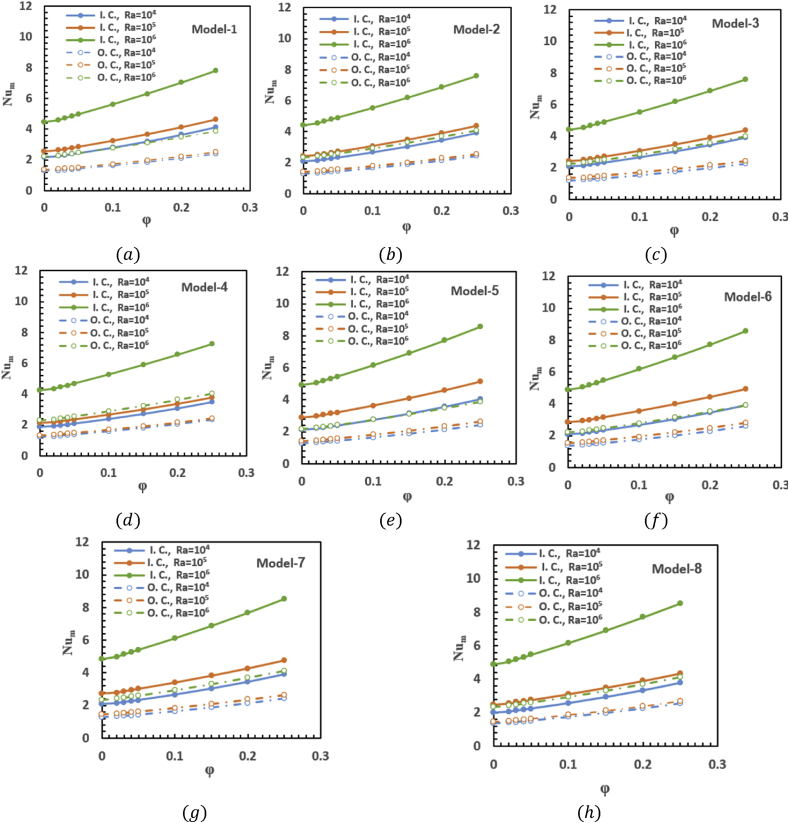

3.3. Average Nusselt number

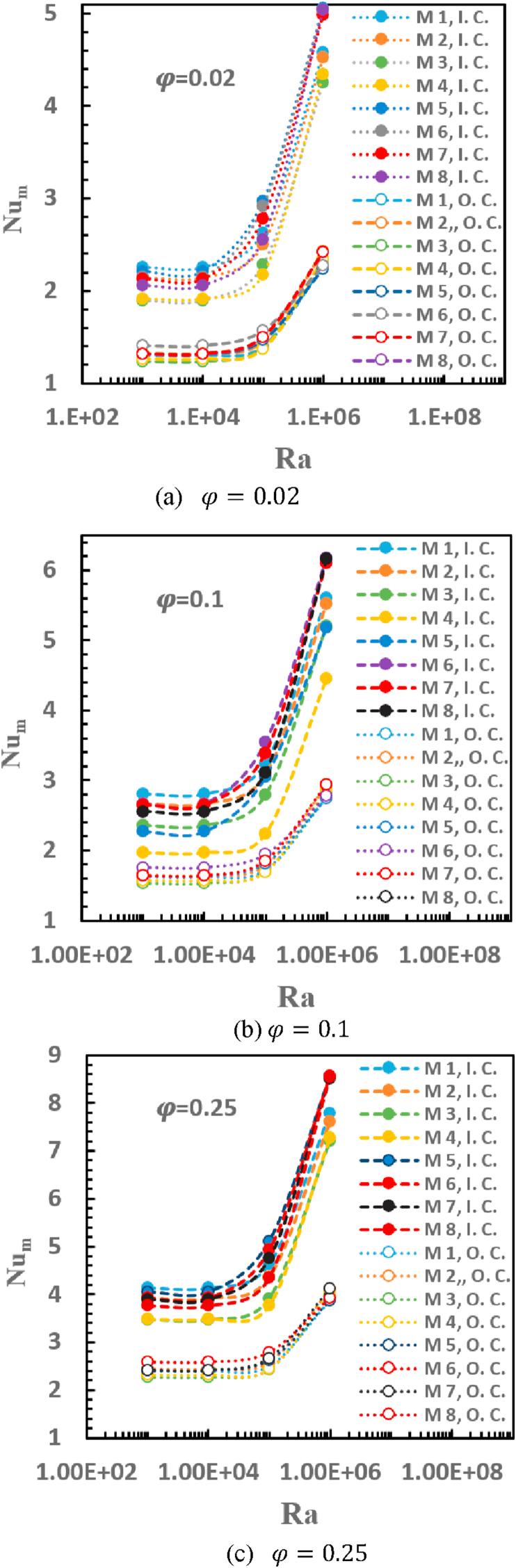

Figure 9 shows the effects of nanoparticles volume fraction on the average Nusselt number for the inner and outer cylinders, for eight models of corrugated annuli at different Rayleigh numbers. Increasing the volume fraction causes an increase in the average of Nusselt number. The reason behind that the heat capacity, density, and thermal conductivity of the nanofluid increase as the nanoparticles volume fractions increase. Moreover, the heat transfer rates from the inner hot cylinder to the nanofluid are higher than similar ones from the nanofluid to the outer cold cylinder. There is no doubt that the heat transfer process enhances with the increase in Rayleigh number because the stronger buoyancy force increases the movement of fluid particles and transport heat to the boundary walls. This leads to accelerating the Nusselt number on the inner hot wall and outer cold wall of the corrugated annulus.

Figure 9.

Variation of average Nusselt number with nanoparticles volume fractions for inner cylinder (I. C.) and outer cylinder (O. C.) for eight models of corrugated annuli at different Rayleigh numbers.

One of the important objectives of the present study is finding the best model giving the highest heat transfer rates. The variation of on the inner and outer walls of corrugated annulus versus Ra for eight models is shown in Figure 10, at three-volume fractions ( = 0.01, 0.1, and 0.25); respectively. The figure shows that there is a slight influence for increasing Ra from 104 to 105 on the average Nusselt number. While, the average Nusselt number increases with an increase in Rayleigh number to 106. The data extracted from the current study reveals that the highest heat transfer rates can be sequenced for the eight models as follows: (5, 6, 7, 8, 2, 1, 3, 4) for the inner hot cylinder, and (6, 8, 7, 5, 2, 1, 3, 4) for the outer cold cylinder. It is noticed that the unsymmetrical models (5, 6, 7, 8) produce the higher heat transfer rate than symmetric models (2, 1, 3, 4). The model-5 produces the highest heat transfer rate than other models. This due to that, one great main vortex is generated in this model witch its intensity increases with the increase in nanoparticle volume fraction. The wide gap of model-5 relatively compared with other models causes growing the large eddies easily which then merge to generate a great main vortex at the top region of the annulus gap. It is seen that increasing the number of undulations of unsymmetrical annulus leads to decreasing the heat transfer rate. Model-4 produces the lowest heat transfer rate than other models. This due to the weak wavy vortex resulted from a high number of undulations for inner and outer corrugated walls (. As a result, the convection currents are moving along the undulation paths leads to producing lower heat transfer rates.

Figure 10.

Mean Nusselt number for the hot and cold cylinders of the corrugated annuli against Rayleigh number.

3.4. Average Nusselt number correlations

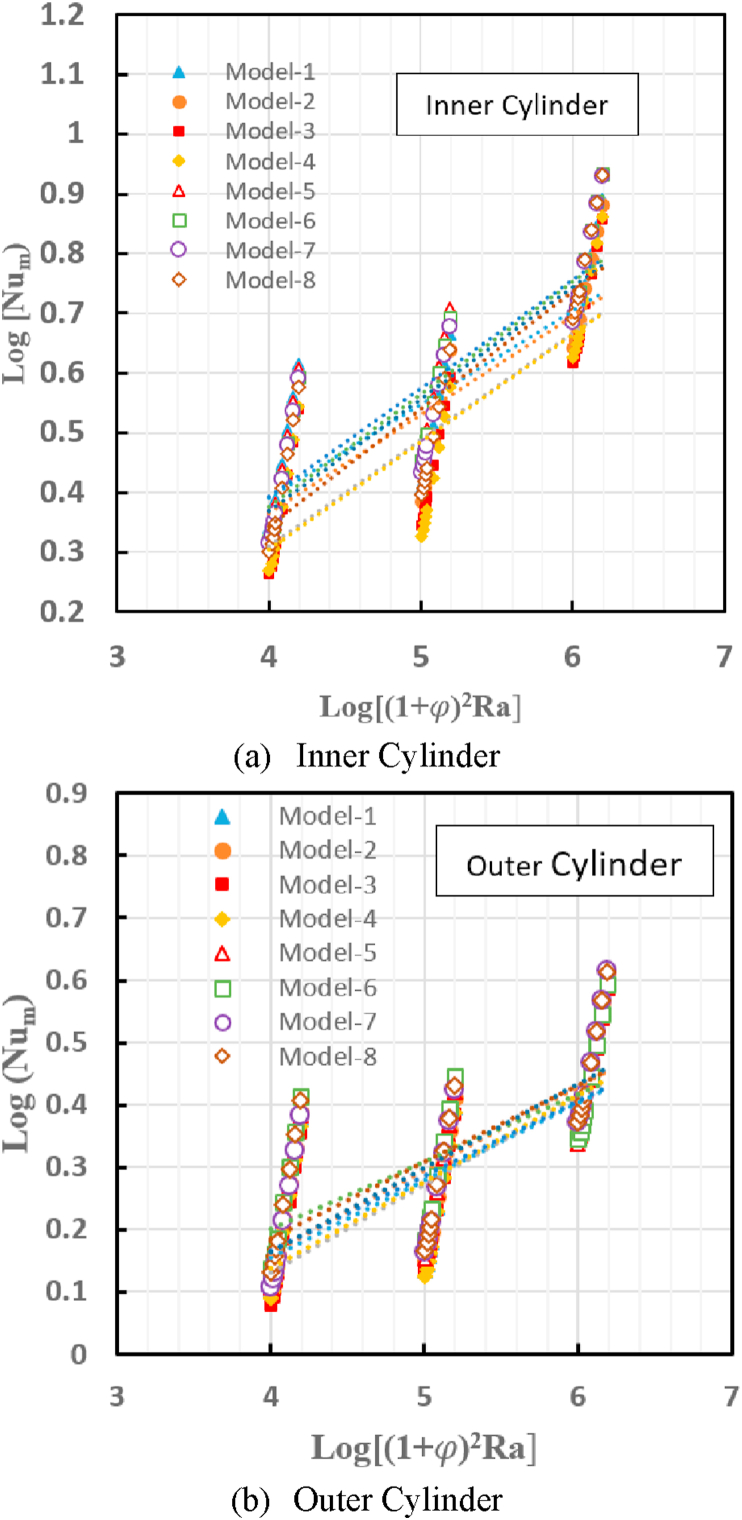

The logarithmic mean Nusselt number for the inner and outer corrugated cylinders against the logarithmic for inner and outer cylinders are shown in Figure 11-a & b; respectively. The ranges of Rayleigh number and volume fraction of nanoparticles are Ra and (; respectively. The general correlation for the average Nusselt number as a function of Rayleigh number and nanoparticles volume fraction has been deduced as follows:

| (27) |

Where c, n, and m are constants given in Table 5.

Figure 11.

Logarithmic mean Nusselt number versus logarithmic for the inner and outer cylinders with different models.

Table 5.

Constants of Eq. (27) for eight models.

|

Inner Cylinder | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | c | n | m |

| 1 | 0.7888 | 0.1571 | 1.1150 |

| 2 | 0.7451 | 0.1649 | 1.1211 |

| 3 | 0.6687 | 0.1783 | 1.1315 |

| 4 | 0.6611 | 0.1798 | 1.1327 |

| 5 | 0.7152 | 0.1818 | 1.1343 |

| 6 | 0.6855 | 0.1886 | 1.1397 |

| 7 | 0.6822 | 0.1878 | 1.1390 |

| 8 |

0.6400 |

0.1972 |

1.1465 |

|

Outer Cylinder | |||

| 1 | 0.7123 | 0.1235 | 1.0894 |

| 2 | 0.6897 | 0.1332 | 1.0967 |

| 3 | 0.6488 | 0.1408 | 1.1025 |

| 4 | 0.6591 | 0.1386 | 1.1008 |

| 5 | 0.7314 | 0.1198 | 1.0867 |

| 6 | 0.7932 | 0.1081 | 1.0778 |

| 7 | 0.6869 | 0.1347 | 1.0978 |

| 8 | 0.7385 | 0.1224 | 1.0885 |

4. Conclusions

The present work displays a numerical study of natural convection heat transfer of H2O-Al2O3 nanofluid inside symmetrical and unsymmetrical corrugated annuli at different nanoparticles volume fractions and Rayleigh numbers. It can be concluded from the current study that:

-

1.

Adding the nanoparticles (Al2O3) to the base fluid leads to more accumulation of the isotherms near the hot wall and an increasing the flow strength and heat transfer rate.

-

2.

Increasing the nanoparticles volume fraction and Rayleigh number leads to increasing the stream function intensity and heat transfer rate.

-

3.

The activity of heated surface increases by increasing the undulations number and making the flow motion tends to be most difficult in the spaces between active undulation walls. This leads to a decrease in the heat transfer rate.

-

4.

The heat transfer rate in unsymmetrical annuli is higher than that in the symmetrical annuli.

-

5.

Model 5 = 3 and = 6) produces the highest heat transfer rate than other models.

-

6.

Model 4 ( = = 8) produces the lowest heat transfer rates than other models.

-

7.

The conduction heat transfer is dominated at a low Rayleigh number. In this case, the isotherms arrange in paths parallel to the shape of annulus walls.

-

8.

There are no significant changes in isotherms contour with the changing of nanoparticles volume fraction.

-

9.

The values and trends of the local Nusselt number for the outer cold cylinder are slightly affected by increasing the undulations number of the inner cylinder (from . While this increase has given a behavior change and increased the rate of heat transfer in the inner cylinder.

-

10.

General correlations of mean Nusselt number for the inner and outer corrugated cylinders as a function of Rayleigh number and nanoparticles volume fraction have been deduced for eight models.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Sattar Aljabair: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Akeel Abdullah Mohammed: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Israa Alesbe: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Laith Jafar Habeeb for support the research with some references and discussions regarding theoretical work and results.

References

- 1.Oosthuizen P.H., Naylor D. Natural convective heat transfer from a cylinder in an enclosure partly filled with a porous medium. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow. 1996;6(6):51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nithiarasu P., Seetharamu K.N., Sundararajan T. Non-Darcy double-diffusive natural convection in axisymmetric fluid saturated porous cavities. Heat Mass Tran. 1997;32:427–433. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getachew D., Poulikakos D., Minkowycz W.J. Double diffusion in a porous cavity saturated with non-Newtonian fluid. J. Thermophys. Heat Tran. 1998;12(3):437–446. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pakdee Watit, Rattanadecho Phadungsak. The 20th Conference of Mechanical Engineering Network of Thailand 18-20 October. Nakhon Ratchasima; Thailand: 2006. Natural convection in porous enclosure caused by partial heating or cooling. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oztop Hakan F. Natural convection in partially cooled and inclined porous rectangular enclosures. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2007;46:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varol Yasin, Oztop Hakan F., Yilmaz Tuncay. Two-dimensional natural convection in a porous triangular enclosure with a square body. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2007;34:238–247. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varol Yasin, Oztop Hakan F., Pop Ioan. Natural convection in right-angle porous trapezoidal enclosure partially cooled from inclined wall. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2009;36:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revnic C., Grosan T., Pop I., Ingham D.B. Magnetic field effect on the unsteady free convection flow in a square cavity filled with a porous medium with a constant heat generation. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2011;54:1734–1742. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra Prakash, Satyamurty V.V. Non-darcian and anisotropic effects on free convection in a porous enclosure. Transport Porous Media. 2011;90:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Shou-Guang, Duan Luo-Bin, Ma Zhe-Shu, Jia Xin-Wang. The study of natural convection heat transfer in a partially porous cavity based on LBM. Open Fuel Energy Sci. J. 2014;7:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowdhury Raju, Abdul Hakim Khan Md., Noor-A-Alam Siddiki Md. Natural convection in porous triangular enclosure with a circular obstacle in presence of heat generation. Am. J. Appl. Math. 2015;3(2):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Yuan-Yuan, Li Ben-Wen, Zhang Jing-Kui. Spectral collocation method for natural convection in a square porous cavity with local thermal equilibrium and non-equilibrium models. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2016;96(May):84–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saravanan S., Brin R.K. Thermal nonequilibrium porous convection in a heat generating medium. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018;135(January):133–145. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammar Abdulkadhim, Abed Azher M., Mohsen1 A.M., Al-Farhany K. Effect of partially thermally active wall on natural convection in porous enclosure. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2018;5(4):395–406. December. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ataei-Dadavi Iman, Chakkingal Manu, Kenjeres Sasa, Kleijn Chris R., Tummers Mark J. Flow and heat transfer measurements in natural convection in coarse-grained porous media. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2019;130:575–584. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanafer Khalil, Vafai Kambiz, Lightstone Marilyn. Buoyancy-driven heat transfer enhancement in a two-dimensional enclosure utilizing nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2003;46:3639–3653. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oztop Hakan F., Eiyad Abu-Nada. Numerical study of natural convection in partially heated rectangular enclosures filled with nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 2008;29:1326–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Nada E., Masoud Z., Hijazi A. Natural convection heat transfer enhancement in horizontal concentric annuli using nanofluids. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2008;35:657–665. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogut Elif Buyuk. Natural convection of water-based nanofluids in an inclined enclosure with a heat source. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2009;48:2063–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abu-Nada E., Oztop H.F. Effects of inclination angle on natural convection in enclosures filled with cu–water nanofluid. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 2009;30(4):669–678. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghasemi S.M. Aminossadati. Periodic natural convection in a nanofluid-filled enclosure with oscillating heat flux. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2010;49:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmoodi Mostafa. Numerical simulation of free convection of nanofluid in a square cavity with an inside heater. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2011;50:2161–2175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bararnia H., Soleimani Soheil, Ganji D.D. Lattice Boltzmann simulation of natural convection around a horizontal elliptic cylinder inside a square enclosure. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2011;38:1436–1442. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheikholeslami M., Gorji-Bandpy M., Ganji D.D., Soleimani Soheil, Seyyedi S.M. Natural convection of nanofluids in an enclosure between a circular and a sinusoidal cylinder in the presence of magnetic field. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2012;39:1435–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasrin Rehena, Alim M.A. Free convective flow of nanofluid having two nanoparticles inside a complicated cavity. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2013;63:191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrizi Abouei, Farhadi M., Shayamehr S. Natural convection flow of Cu–Water nanofluid in horizontal cylindrical annuli with inner triangular cylinder using lattice Boltzmann method. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habibi Matin M., Pop I. Natural convection flow and heat transfer in an eccentric annulus filled by Copper nanofluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2013;61:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sourtiji E., Ganji D.D., Seyyedi S.M. Free convection heat transfer and fluid flow of Cu–water nanofluids inside a triangular–cylindrical annulus. Powder Technol. 2015;277:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravnik J., Škerget L. A numerical study of nanofluid natural convection in a cubic enclosure with a circular and an ellipsoidal cylinder. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2015;89:596–605. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sourtiji E., Ganji D.D., Seyyedi S.M. Free convection heat transfer and fluid flow of Cu–water nanofluids inside a triangular–cylindrical annulus. Powder Technol. 2015;277:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatami M., Song D., Jing D. Optimization of a circular-wavy cavity filled by nanofluid under the natural convection heat transfer condition. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2016;98:758–767. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatami M., Safari H. Effect of inside heated cylinder on the natural convection heat transfer of nanofluids in a wavy-wall enclosure. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2016;103:1053–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalidasan K., Rajesh Kanna P. Natural convection on an open square cavity containing diagonally placed heaters and adiabatic square block and filled with hybrid nanofluid of nanodiamond - cobalt oxide/water. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2017;81:64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehryan S.A.M., Kashkooli Farshad M., Ghalambaz Mohammad, Chamkha Ali J. Free convection of hybrid Al2O3-Cu water nanofluid in a differentially heated porous cavity. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dogonchi A.S., Ismael Muneer A., Chamkha Ali J., Ganji D.D. Numerical analysis of natural convection of Cu–water nanofluid filling triangular cavity with semicircular bottom wall. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018 published online 10 july 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guestala Mabrouk, Kadja Mahfoud, Hoang Mai Ton. Study of heat transfer by natural convection of nanofluids in a partially heated cylindrical enclosure. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2018;11:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddiqa Sadia, Begum Naheed, Hossain M.A., Rama Subba, Gorla Reddy. Numerical solutions of free convection flow of nanofluids along a radiating sinusoidal wavy surface. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2018;126:899–907. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mebarek-Oudina F. Convective heat transfer of Titania nanofluids of different base fluids in cylindrical annulus with discrete heat source. Heat Tran. Asian Res. 2019;48:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surendar Aravindhan, Muralidharan J., Saee Ali Dehghan, Maseleno Andino, Rudenko Aleksandr Alekseevich, Ross David. Mathematical modelling of free convection in an ellipse-rectangular annulus filled with nanofluid using LBM. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progr. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mebarek-Oudina F., Aissa A., Mahanthesh B., Oztop H.F. Heat transport of magnetized Newtonian nanoliquids in an annular space between porous vertical cylinders with discrete heat source. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2020;117:104737. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzougui S., Mebarek-Oudina F., Aissa A., Magherbi M., Shah Z., Ramesh K. Entropy generation on magneto-convective flow of copper-water nanofluid in a cavity with chamfers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouzerzour Abdeslem, Djezzar Mahfoud, Oztop Hakan F., Tayebi Tahar, Abu-Hamdeh Nidal. Natural convection in nanofluid filled and partially heated annulus: effect of different arrangements of heaters. PhysicaA. 2020;538:122479. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu Yu-Peng, Li You-Rong, Lu Liang, Mao Yong-Jian, Li Ming-Hai. Natural convection of water-based nanofluids near the density maximum in an annulus. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020;152:106309. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasanuzzamana M., Saidura R., Alib M., Masjukia H.H. Effects of variables on natural convective heat transfer through V-corrugated vertical plates. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2007;2(2):109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasan Noman, Saha Sumon, Feroz Chowdhury Md. Proceedings of the 4th BSME-ASME International Conference on Thermal Engineering, Dhaka/Bangladesh, 27-29 December. 2008. Natural convection within an enclosure of sinusoidal coregulated top surface. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasan Muhammad Noman, Saha Suvash C., Gu Y.T. Unsteady natural convection within a differentially heated enclosure of sinusoidal corrugated side walls. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2012;55(21-22 October):5696–5708. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain Salam Hadi, Sabah Riyadh, Ali Farooq Hassan. Numerical study of natural convection heat transfer of air flow inside a corrugated enclosure in the presence of an inclined heated plate. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dynam. Int. J. 2013;13(No. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morsli Souad, Sabeur-Bendehina Amina. Numerical study on natural convection and entropy generation in squares and corrugated cavities. J. Phys. Conf. 2015;574:1–6. 012113. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chordiya Jayesh Subhash, Sharma Ram Vinoy. Numerical study on effect of corrugated diathermal partition on natural convection in a square porous cavity. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2019;33:2481–2491. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takabi Behrouz, Salehi Saeed. Augmentation of the heat transfer performance of a sinusoidal corrugated enclosure by employing hybrid nanofluid. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2015;6(Feb):16. Article ID 147059. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saha Goutam. Heat transfer behavior inside a sinusoidal cavity using water based TIO2 nanofluid. GANIT J. Bangladesh Math. Soc. 2017;37:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell Leonard, Mozumder Aloke K., Mahmud Shohel, Das Prodip K. Natural convection of Al2O3-water nanofluid in a wavy enclosure. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017;1851:020003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadripour Soroush, Ghorashi Seyed Amin, Estajloo Mohammad. Numerical investigation of a corrugated heat source cavity: a full convection-conduction-radiation coupling. Am. J. Aero. Eng. 2017;4(3):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aich Walid. 3D buoyancy induced heat transfer in triangular solar collector having a corrugated bottom wall. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2018;8(2):2651–2655. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammar Abdulkadhim, Hamzah Hameed K., Ali Farooq H., Abed Azher M., Abed Isam Mejbel. Natural convection among inner corrugated cylinders inside wavy enclosure filled with nanofluid superposed in porous–nanofluid layers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Tran. 2019;109(December):1043–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parveen Rujda, Mahapatra T.R. Numerical simulation of MHD double diffusive natural convection and entropy generation in a wavy enclosure filled with nanofluid with discrete heating. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dutta Shantanu, Pati Sukumar, Biswas Arup Kumar. Thermal transport analysis for natural convection in a porous corrugated rhombic enclosure. Heat Transfer. 2020;49:3287–3313. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alhashash Abeer. Free convection from a corrugated heated cylinder with nanofluids in a porous enclosure. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020;12(8):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khalili Ebrahim, Ahmad Saboonchi, Saghafian Mohsen. Natural convection of Al2O3 nanofluid between two horizontal cylinders inside a circular enclosure. Heat Tran. Eng. 2017;38(2):177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho C.-J., Chen M., Li Z. Numerical simulation of natural convection of nanofluid in a square enclosure: effects due to uncertainties of viscosity and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2008;51(17–18):4506–4516. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghasemi B., Aminossadati S. Natural convection heat transfer in an inclined enclosure filled with a water-CuO nanofluid. Num. Heat Transf. Part A. 2009;55(8):807–823. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Zamily A.M.J. Analysis of natural convection and entropy generation in a cavity filled with multi-layers of porous medium and nanofluid with a heat generation. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2017;106:1218–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kahveci K. Buoyancy driven heat transfer of nanofluids in a tilted enclosure. J. Heat Tran. 2010;132(6) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dogonchi A.S., Sheremet M.A., Ganji D.D., Pop I. Free convection of copperwater nanofluid in a porous gap between hot rectangular cylinder and cold circular cylinder. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blazek Jiri. 2015. Computational Fluid Dynamics: Principles and Applications. Book • third ed. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim B.S., Lee D.S., Ha M.Y., Yoon H.S. A numerical study of natural convection in a square enclosure with a circular cylinder at different vertical locations. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2008;51:1888–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moukalled F. Natural convection in the annulus between concentric horizontal circular and square cylinders. J. Thermophys. Heat Tran. 1996;10(3):524–531. July-September. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abu-Nadaa Eiyad, Oztopcd Hakan F. Numerical Analysis of Al2O3/Water Nanofluids Natural Convection in a Wavy Walled Cavity. Num. Heat Transf. Part A: Appl. 2011;59(5):403–419. February. [Google Scholar]