Abstract

A program of comparing American (NASA) and Russian (ROSCOSMOS) space radiation transport codes has recently begun, and the first paper directly comparing the NASA and ROSCOSMOS space radiation transport codes, HZETRN and SHIELD respectively has recently appeared. The present work represents the second time that NASA and ROSCOSMOS calculations have been directly compared, and the focus here is on models of pion production cross sections used in the two transport codes mentioned above. It was found that these models are in overall moderate agreement with each other and with experimental data. Disagreements that were found are discussed.

Future exploration-class human space missions will continue to rely heavily on international cooperation, and a program has recently begun with the aim of comparing space radiation calculations between the American (NASA) and Russian (ROSCOSMOS) space agencies. This activity has involved several workshops in Moscow, with radiation experts sharing calculations and results from a wide variety of space radiation topics. The activity has recently expanded to include other space agencies from Europe, Japan and Canada. The first published paper to come out of these meetings has recently appeared [1]. That work focused on transport code flux predictions and represented the first time that the NASA and ROSCOSMOS space radiation transport codes, HZETRN [2, 3] and SHIELD [4, 5], respectively, had been directly compared to each other. (HZETRN stands for High charge (Z) and Energy TRaNsport.) An extensive discussion of the HZETRN and SHIELD codes is presented in that work [1] and will not be repeated in this Short Communication.

Recent work has shown that pion production can make a large contribution to the space radiation dose1 received from galactic cosmic ray (GCR) particles under realistic shielding scenarios [6, 7, 8]. Therefore, it is important that space radiation transport codes are able to accurately calculate pion production flux. Consequently, the pion production cross sections, which are used by transport codes, must be accurately modeled. HZETRN has recently been extended to include pion contributions and the associated electromagnetic cascade process [8, 9], and because of this recent advance with HZETRN, there is special interest in comparing pion production models with other transport codes.

The first paper that studied comparisons between HZETRN and SHIELD [1] also included a comparison of pion flux calculated by transporting the full GCR energy spectrum for the H, O and Fe projectile components being separately transported through various thicknesses of Al shielding (1, 10, 100 g/cm2). That study also included comparisons with the FLUKA code [10]. It was found that HZETRN, SHIELD and FLUKA were in excellent agreement for thick (100 g/cm2) shielding for H, O, and Fe projectiles and also excellent agreement for high energy pion production from H projectiles for thinner (1, 10 g/cm2) shielding. However, for thinner (1, 10 g/cm2) shielding, poor agreement with HZETRN was obtained for O and Fe projectiles and for lower energy pion production from H projectiles, with HZETRN results significantly smaller than SHIELD and FLUKA. These differences for thinner shielding were thought to be due to differences in nuclear models which are expected to manifest themselves for thin shields. However, to properly investigate this hypothesis, one needs to compare nuclear models directly, which is part of the motivation for the present work. In particular, why did HZETRN give consistently smaller results than SHIELD for the previous thick target transport study [1]? Was the reason because of smaller cross sections or differences in transport methods?

A paper has been previously published by Werneth, Norbury and Blattnig [11] which compared two different pion production cross section models to experimental data. The first model was a simple Thermal model parameterization [12, 13] based on a Boltzmann distribution, while the second model was the high energy parameterization of Badhwar [14, 15, 16] based on Feynman scaling. The paper [11] made recommendations as to which model should be included in the HZETRN code, and these recommendations have now been implemented, so that the current pion cross section model used in the HZETRN code consists of the Thermal model [12, 13] for low projectile kinetic energies, KE ≤ 1 GeV/n, the Badhwar model [14, 15, 16] for high energies, KE ≥ 5 GeV/n, and a blend of both models for the intermediate energy region, 1 GeV/n < KE < 5 GeV/n. The method of how to blend the models in the intermediate energy region is discussed by Slaba et al. [17] and is applied in log energy space, so that for example, at the mid-point in log space (KE=2.2 GeV/n) the HZETRN code calculates the pion cross section as one half Thermal model and one half Badhwar model.

The present work is a Short Communication and represents an addendum to the previously published pion cross section paper [11]. Figures 3 - 15 of reference [11] are reproduced here with the addition of the corresponding HZETRN and SHIELD MonteCarlo calculations as Figures 1 - 11. The aim is to compare the pion cross section model used by NASA in the HZETRN [2, 3] transport code to the pion cross section model used by ROSCOSMOS in the SHIELD [4, 5] transport code, and also to see whether one model provides a better comparison to the data previously studied [11].

Figure 1:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for p + 64Cu reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 3 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Proton kinetic energy values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 400, 450, 500 MeV have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 46, = 26.

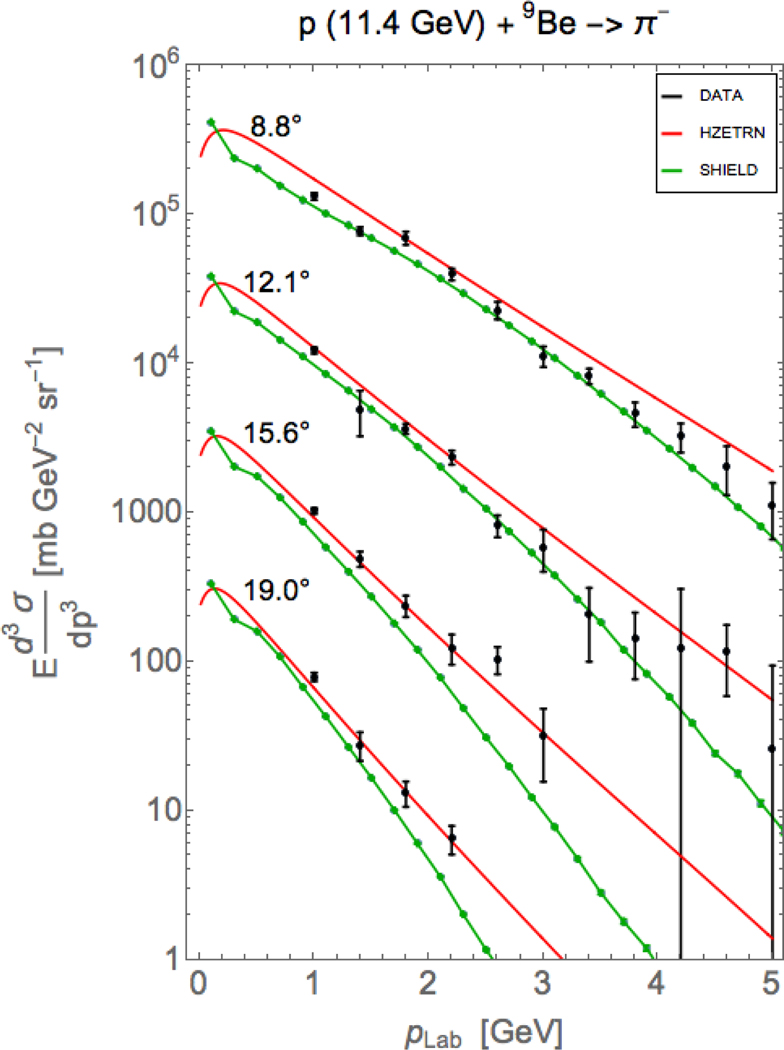

Figure 11:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for p + 9Be reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 15 of reference [11], where the Badhwar model is now identified as HZETRN. Some data points at various angles with large error bars reaching to 0 lie on top of each other. Such points have been very slightly shifted in energy so that they can be visually distinguished. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 15.6°, 12.1°, 8.8° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 3, = 1.

In order to obtain a quantitative estimate of the agreement between transport code cross section predictions xi and experimental data mi, the average chi squared is defined

| (1) |

where N is the number of data points. The values are listed in every figure caption. The values of mi are the data reported without consideration of the error bars. Obviously, a more sophisticated method [18] could be used, but the method of equation (1) is chosen to obtain a simple quantitative estimate of how the two transport codes compare to data.

Figures 1 - 6 show results for the low projectile kinetic energy region, KE < 1 GeV/n, where both the SHIELD and HZETRN cross section models are in moderate agreement with data, as seen from qualitative inspection of the plots together with the listed values, although there are large differences with data at low pion momentum seen in Figures 2 and 4. Figures 7 - 8 show results for the intermediate projectile kinetic energy region, 1 GeV/n < KE < 5 GeV/n, with SHIELD performing generally better than HZETRN. Figures 9 - 11 show results for the high projectile kinetic energy region, KE > 5 GeV/n. Note that all projectiles in this region are protons only. In Figure 9, all models are in comparable agreement with the data, which sometimes has large uncertainties. In Figures 10 - 11, the HZETRN and SHIELD models are in similar agreement with data, again as seen from qualitative inspection of the plots together with the listed values, although SHIELD shows somewhat larger differences with data at higher pion momentum in Figure 11.

Figure 6:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 139La + 139La reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Figs. 9 and 10 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 70°, 60°, 50°, 40°, 30° 20° have been multiplied by 10, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, respectively. = 1443, = 1136.

Figure 2:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 4He + 27Al reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 4 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 110°, 90°, 70° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 149, = 145.

Figure 4:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 20Ne + 27Al reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 6 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 110°, 90°, 70° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 131, = 423.

Figure 7:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for p + 12C reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 11 of reference [11], where a blend of the Thermal and Badhwar models is now identified as HZETRN. Proton kinetic energy values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 2.1 GeV have been multiplied by 10. = 4, = 36.

Figure 8:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 12C + 12C reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 12 of reference [11], where a blend of the Thermal and Badhwar models is now identified as HZETRN. 12C kinetic energy values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 2.1 GeV/n have been multiplied by 10. = 35, = 57.

Figure 9:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for p + 9Be reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 13 of reference [11], where the Badhwar model is now identified as HZETRN. Some data points at various angles with large error bars reaching to 0 lie on top of each other. Such points have been very slightly shifted in energy so that they can be visually distinguished. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 14.6°, 9.1°, 4.1° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 2, = 6.

Figure 10:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for p + 9Be reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 14 of reference [11], where the Badhwar model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 15.6°, 12.1°, 8.8° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 2, = 2.

Summary & Conclusions:

(1) Overall, the HZETRN and SHIELD codes compare to experimental data with total values, = 597 and = 403, obtained by considering all the data. (These numbers are obtained by averaging over the entire data set; not averaging the figures.) These numbers are meant to give nothing more than a simple quantitative idea of the relative comparisons of SHIELD and HZETRN to the data, and represent a simple quantitative supplement to qualitative inspection of the figures. (2) The HZETRN pion cross sections are often smaller than SHIELD for projectile energies below 5 GeV and larger than SHIELD above that energy. (3) Overall, differences between the transport codes and data are moderate. Given that pions can make a large contribution to dose [6, 7, 8], improvements to the pion production cross section models used in transport codes would be useful, especially where models show larger disagreements with data.

Figure 3:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 40Ar + 40Ca reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Fig. 5 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 110°, 90°, 70° have been multiplied by 10, 100, 1000 respectively. = 427, = 804.

Figure 5:

Inclusive pion production cross sections for 40Ar + KCl reactions. SHIELD calculations have been added to Figs. 7 and 8 of reference [11], where the Thermal model is now identified as HZETRN. Pion lab angle values are listed adjacent to each plot. Plots for 110°, 90°, 60°, 40°, 30°, 20° 15° have been multiplied by 10, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 respectively. = 645, = 228.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Advanced Exploration Systems (AES) Division under the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate of NASA. We wish to thank Tony Slaba for useful correspondence regarding the blend of models in the intermediate energy region.

Footnotes

Note that the large contribution is to absorbed dose, not dose-equivalent.

References

- [1].Norbury JW, Slaba TC, Sobolevsky N, Reddell B, Life Sci. Space Res 14 (2017) 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wilson JW, Slaba TC, Badavi FF, Reddell BD, Bahadori AA, Life Sci. Space Res 4 (2015) 46; ibid. 7 (2015) 27; ibid. 9 (2016) 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Slaba TC, Wilson JW, Badavi FF, Reddell BD, Bahadori AA, Life Sci. Space Res 9 (2016) 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dementyev AV, Sobolevsky NM, Rad. Meas 30 (1999) 553. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Denisov AN, Kuznetsov NV, Nymmik RA, Panasyuk MI, Sobolevsky NM Acta Astron. 68 (2011) 1440. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Aghara SK, Blattnig SR, Norbury JW, Singleterry RC, Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 267 (2009) 1115. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Norman RB, Blattnig SR, De Angelis G, Badavi FF, Norbury JW, Adv. Space Res 50 (2012) 146. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Slaba TC, Blattnig SR, Reddell B, Bahadori A, Norman RB, Badavi FF, Adv. Space Res 52 (2013) 62. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Norman RB, Slaba TC, Blattnig SR, Adv. Space Res 51 (2013) 2251. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Battistoni G. et al. , Ann. Nucl. Energy 82 (2015) 10. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Werneth CM, Norbury JW, Blattnig SR, Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. B 298 (2013) 86. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nagamiya S, Lemaire MC, Moeller E, Schnetzer S, Shapiro G, Steiner H, Tanihata I, Phys. Rev. C 24 (1981) 971. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Norbury JW, Phys. Rev. C 79 (2009) 037901. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Badhwar GD, Stephens SA, Golden RL, Phys. Rev. D 15 (1977) 820. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Blattnig SR, Swaminathan SR, Kruger AT, Ngom M, Norbury JW, Phys. Rev. D 62 (2000) 094030. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Norbury JW, Townsend LW, Phys. Rev. D 75 (2007) 034001. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Slaba TC, Blattnig SR, Tweed J, J. Comp. Phys 233 (2013) 464. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Norman RB, Blattnig SR, J. Comp. Phys 234 (2013) 217. [Google Scholar]