Summary

Sexual reproduction shuffles the parental genomes to generate new genetic combinations. To achieve that, the genome is subjected to numerous double-strand breaks, the repair of which involves two crucial decisions: repair pathway and repair template [1]. Use of crossover pathways with the homologous chromosome as template exchanges genetic information and directs chromosome segregation. Crossover repair, however, can compromise the integrity of the repair template and is therefore tightly regulated. The extent to which crossover pathways are used during sister-directed repair is unclear, because the identical sister chromatids are difficult to distinguish. Nonetheless, indirect assays have led to the suggestion that inter-sister crossovers, or sister chromatid exchanges (SCEs), are quite common [2–11]. Here we devised a technique to directly score physiological SCEs in the C. elegans germline using selective sister chromatid labeling with the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU). Surprisingly, we find SCEs to be rare in meiosis, accounting for <2% of repair events. SCEs remain rare even when the homologous chromosome is unavailable, indicating that almost all sister-directed repair is channeled into noncrossover pathways. We identify two mechanisms that limit SCEs. First, SCEs are elevated in the absence of the RecQ helicase BLMHIM-6. Second, the Synaptonemal Complex - a conserved interface that promotes crossover repair [12,13] - promotes SCEs when localized between the sisters. Our data suggest that crossover pathways in C. elegans are only used to generate the single necessary link between the homologous chromosomes. Noncrossover pathways repair almost all other breaks, regardless of the repair template.

eTOC Blurb

Identical sister chromatids have proven difficult to study. Almanzar et al. have developed a new way to label individual sisters and score exchanges between them. This analysis reveals that meiotic sister exchanges are rare in C. elegans. Sister exchanges are antagonized by the RecQ helicase BLMHIM-6 and can be promoted by the synaptonemal complex.

Graphical Abstract

Results and Discussion

Selective labeling of a single sister chromatid using EdU

During meiosis, chromosomes receive multiple double-strand breaks (DSBs), but undergo only a very limited number of inter-homolog exchanges, or crossovers [1,14–16]. These repair events manifest as chiasmata, the obligate physical links that promote correct segregation of the homologous chromosomes (homologs). The remaining breaks are repaired by alternative methods, including repair using the homolog without exchange of flanking sequences (noncrossover), and repair using the sister chromatid as a template, forming both crossovers and noncrossovers. While multiple mechanisms bias meiotic repair toward the homolog to ensure chromosome segregation [4], the prevalence and regulation of sister-directed repair is poorly understood, largely due to challenges in distinguishing the identical sisters and consequently, the resulting repair products. SCEs, unlike inter-sister noncrossover products, can be directly identified using nucleotide analogs [17–20]. However, these assays have not been extensively applied to modern model systems where meiotic recombination is well characterized and SCE etiology can be ascertained. To address this, we took advantage of the cytological and genetic amenability of C. elegans, and developed a way to selectively label individual sister chromatids. This allowed us to quantify physiological SCEs and to study SCE regulation.

We devised a pulse/chase method that results in only one sister containing the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU). The distal end of the C. elegans gonad is populated by mitotically dividing germline nuclei that eventually enter meiosis and progress through meiotic prophase as they travel through the gonad (Figure 1A). We exposed worms to a short pulse of EdU via soaking, allowing it to be incorporated into newly replicated DNA for one mitotic S-phase (Figures 1B and S1A; [15,21,22]). Chase times were then optimized such that labeled nuclei would enter meiosis, undergo pre-meiotic S-phase without EdU, and complete meiotic prophase, resulting in one of the strands of one of the two sisters containing EdU. (An additional mitotic cycle without EdU prior to meiotic entry would result in a combination of one or no EdU-containing sisters in each chromosome; see Figure S1B). The azide group on EdU can be labeled with an organic dye using ‘click’ chemistry [23], which is easily compatible with other labeling modalities and does not require DNA denaturation, unlike antibody labeling of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU; [24]).

Figure 1: A new method to visualize meiotic SCEs using selective labeling with EdU.

A. Overview of pulse/chase experiment. Nuclei undergoing DNA replication in the mitotic zone of the gonad incorporate EdU (green). After removal of EdU, the labeled nuclei continue dividing asynchronously until meiotic entry (crescent-shaped nuclei). The labeled nuclei progress through meiosis as they move through the gonad, and are remodeled in diakinesis into condensed structures that allow visualization of individualized sisters. Bottom, an image of a wild-type C. elegans gonad labeled with EdU and chased for 28 hours at 25°C. A labeled nucleus in diakinesis is marked with a dashed box. Note the asynchronous distribution of the labeled nuclei. See Figure S1A for further details. Blue, DNA (DAPI); Green, EdU.

B. Schematic illustrating single sister EdU labeling. Chromosomes undergo mitotic DNA replication in the presence of EdU (green), resulting in one EdU-containing strand in each sister. Following pre-meiotic DNA replication without EdU, labeling is reduced to one strand of one sister per homolog pair. In meiotic prophase, the meiotic chromosome axis (pink) appears at the interface between the homologs. When visualized as a condensed bivalent in diakinesis, sister chromatids are clearly resolvable, with the axis now delineating the interface between the sisters. Inset, a confocal image of bivalents harboring or lacking an exchange (left and right, respectively) with interpretative diagrams to the right. The nucleus harboring the exchange bivalent underwent an extra round of DNA replication without EdU before entering meiosis, resulting in labeling of only one of the four sisters. See Figure S1B for a related illustration. Blue, DNA (DAPI); red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU. Scale bars = 1μm.

C. EdU incorporation does not cause measurable DNA damage or affect bivalent formation. Analysis of bivalent formation in wild-type and him-8 spo-11(−) worms, which lack meiotic DSBs. (him-8 is present in this background due to genetic linkage with spo-11, but this does not impact the result.) DSB formation in him-8 spo-11(−) animals would result in chiasmata and bivalent formation; no bivalents were observed among the EdU labeled chromosomes. The presence of univalents in wild-type animals would have indicated failure to form chiasmata; no such incidence were observed in the presence or absence of EdU. N values indicate the number of chromosomes counted per genotype. See Figure S2B–C for further analysis.

At the end of meiotic prophase (diakinesis) chromosomes condense and sister chromatids individualize. The paired homologs are linked together by chiasmata, forming a cruciform-like bivalent. Each sister is on either side of the meiotic chromosome axis, which determines the division plane in the ensuing meiotic divisions (stained throughout with antibodies against the axis protein HTP-3 [25–27]; Figure 1B, inset). By combining EdU labeling with DAPI staining of bulk chromatin we directly visualized single sister chromatids. At this stage we could confidently identify SCEs, which manifest as an EdU signal traversing the axis, analogous to the so-called “harlequin chromosomes” ([17,18]; Figure 1B, inset; see also Figures S1B and S2A).

We wanted to address the potential impact of our experimental approach on genome integrity and DNA repair. In worms lacking endogenous meiotic DSBs even a single break is sufficient for chiasma formation [15,16], providing us with a sensitive readout for DNA damage. In animals lacking SPO-11, the enzyme that catalyzes meiotic DSBs [28], the homologs do not form a chiasma, and therefore condense as two unassociated oval univalents, with the two sisters on either side of the axis. EdU incorporation did not significantly induce chiasmata in this background (Figures 1C and S2B–C), indicating that EdU substitution does not induce DNA breaks in meiotic prophase. Wild-type animals labeled with EdU can still form bivalents (Figures 1C and S2B–C), indicating no significant perturbation of the crossover repair pathway. In these animals we also did not observe any chromosome fragmentation (N=183 EdU labeled chromosomes) suggesting DNA repair was functional. We conclude that our EdU labeling approach can reliably capture physiological sister-directed repair, overcoming challenges reported for BrdU labeling [29,30].

SCEs are a rare outcome of meiotic DNA repair

When we applied our single-sister labeling approach to wild-type animals, we observed only 4% of chromatids harboring exchanges, indicating a low level of SCEs (2/49 chromosomes; Figure 2A; all SCE counts are summarized in Table S1; statistically significant pairwise comparisons are noted throughout). This result might stem from a very strong bias for homolog-directed repair, which in C. elegans can only occur between already paired homologs. To investigate whether SCEs are elevated when only the sister chromatid is available as a template for repair, we used him-8 animals where the X chromosome fails to pair with its homolog and engage in homolog-directed repair. In him-8 worms programmed DSBs are formed and are eventually repaired, albeit with delayed kinetics [31]. Even in this condition we observed very few exchange chromatids (1/24 univalents; Figure 2A–B), indicating that competition with the homolog is not the reason for the paucity of SCEs. Alternative pathways that do not use a repair template, such as canonical nonhomologous end-joining (c-NHEJ), single-strand annealing (SSA) or theta-mediated end-joining (TMEJ), are thought to be rarely used during C. elegans meiosis [32–35]. Nonetheless, we directly examined the role of c-NHEJ by eliminating DNA ligase IV (lig-4; [36]). While breaks form and are efficiently repaired in lig-4; him-8 worms, we observed very few SCEs on both univalents and bivalents (0/28 and 1/55, respectively; Figure 2A), indicating that the low rate of SCEs in him-8 animals does not stem from breaks being channeled to c-NHEJ. Taken together, these data indicate that SCEs are a rare outcome of meiotic DSB repair, whether or not the homolog is available, and that sister-directed repair during meiosis almost always results in noncrossovers.

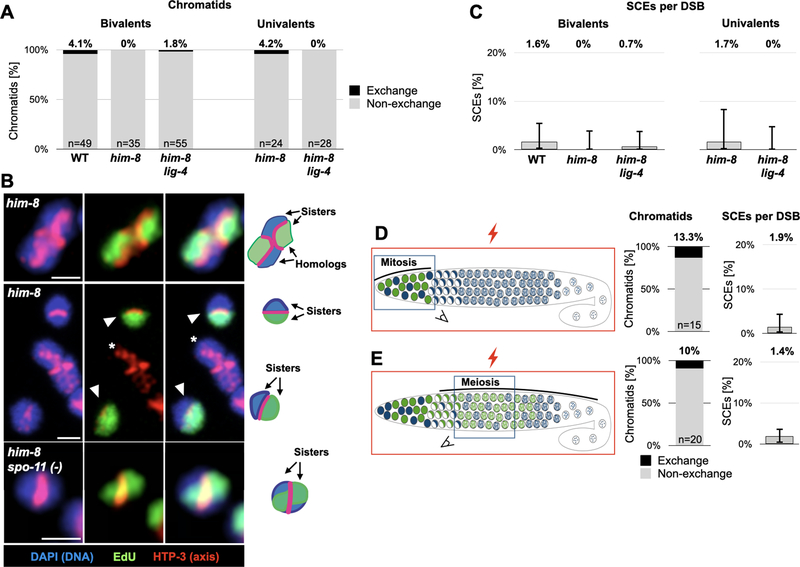

Figure 2: SCEs are rare outcome of meiotic DSB repair.

A. Exchange chromatids are rare, regardless of the availability of the homolog. Exchange and non-exchange chromatids on bivalent and univalent chromosomes in wild-type worms, in worms deficient for X chromosome pairing (him-8) and in worms defective for both X chromosome pairing and non-homologous end-joining (him-8; lig-4). N values indicate the number of chromatids counted for each genotype. Results were not significant for all pairwise comparisons with wild-type chromosomes (p>.05, Pearson’s chi-squared test). See also Table S1.

B. Representative cytology of bivalents and univalents. Top, a single sister of each homolog pair from him-8 animals labeled with EdU, with no exchanges in either of the long arms. Middle, two unpaired univalent X chromosomes (arrowheads) in him-8 animals, each with a single sister chromatid labeled with EdU, and no exchanges. An autosome bivalent (asterisk) is not labeled due to the different replication time of the X chromosome and the autosomes [62]. Bottom, univalent chromosomes in irradiated him-8 spo-11(−) animals with a single sister chromatid labeled with EdU, and an SCE. Note the EdU signal crossing the axis. Red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU, Blue, DNA (DAPI). Interpretive diagrams are shown on the right. Scale bars = 1μm.

C. SCEs are a rare outcome of meiotic DSB repair. Rates of SCE formation per DSB calculated using an estimate of 5 DSBs per homolog pair (2.5 per chromosome). Numbers represent the average rate a DSB resulted in an SCE. Error bars represent 95% exact binomial confidence intervals.

D. Direct quantification reveals that SCEs are a rare outcome of exogenous DSBs. Left, cartoon of irradiation experiment. him-8 spo-11(−) worms that are deficient for endogenous DSBs are labeled with EdU and exposed to 5000 rads X-ray irradiation (an average of 7 DSBs per chromosome). While the whole worms were subject to irradiation (red box), the nuclei in the mitotic zone (D) and meiotic prophase (E) reached diakinesis at time of dissection (indicated by blue squares). Middle, observed exchange chromatids. N values indicate the number of chromatids counted for each genotype. Right, rate of SCEs as a fraction of total DSB repair events. Error bars represent 95% exact binomial confidence intervals. See also Table S1.

The prevalence of exchange chromatids counted above (Figure 2A) overestimates the rate of SCE formation, since each chromosome is subjected to multiple DSBs. However, the number of meiotic DSBs in C. elegans remains controversial, with results from different assays ranging from 2 to more than 8 per homolog pair [13–15,37]. Therefore, in the experiments above we could only estimate the rate at which a DSB repair event results in an SCE, revealing rates of 1–2% SCEs per DSB in the various conditions we tested (Figure 2C; calculated using an estimate of 5 DSBs per homolog pair, or 2.5 DSBs per chromosome; 95% exact binomial confidence intervals are shown). In the case of him-8 and lig-4; him-8 animals this is likely a conservative estimate, since these mutants seem to incur additional breaks compared with wild-type animals [38,39]. To allow for direct quantification of the rate of SCE formation we induced a known number of DSBs in mitotic or meiotic nuclei using X-ray irradiation in him-8 spo-11(−) animals that lack endogenous breaks (Figure 2D–E). We irradiated the entire gonad at different times following EdU labeling, and identified the cell cycle stage at the time of DSB induction using chromosome morphology: chromosomes subjected to DSBs in meiosis subsequently formed bivalents connected by chiasmata, whereas chromosomes subjected to DSBs in the mitotic zone condensed as univalents [28]. Upon induction of an average of 7 DSBs/chromosome (see Methods for details), mitotic and meiotic nuclei harbored 13.3% and 10% exchange chromatids, respectively. This rate translates to 1.9% and 1.4% of DSBs repaired as SCEs (Figure 2D–E). The similar low rate of meiotic SCEs induced by irradiation and the estimated rate for endogenous DSBs suggests that neither the nature of X-ray induced breaks nor their genomic location play a significant role in determining repair outcomes. Furthermore, our analysis of mitotic chromosomes and of unpaired homologs in meiosis suggests that the low rate of SCEs is not a result of interaction or competition with the homolog.

Investigations of inter-sister repair have typically measured imperfect repair products between repeated elements, where the homolog is not available and only sister-directed repair can occur (e.g., [3]). These studies, like our data, indicate a disfavoring of crossover versus noncrossover outcomes during meiotic inter-sister repair. This conclusion received further substantiation in recent work in C. elegans [40].

Our labeling approach also enabled us to measure the frequency of SCEs in unperturbed meiosis, revealing that 4% of chromatids harbor an exchange, and 1.4–1.7% of DSBs are repaired as SCEs. Basal SCE rates of 10–20% were reported on both the Drosophila X chromosome and on chromosome III in budding yeast [2,5,6,11]. However, these measurements were made in cells with altered karyotype, relying on topological entrapments caused by SCEs in circular (or “ring”) chromosomes. In yeast, repair intermediates could be identified using physical assays that rely on obtaining synchronous cultures where specific loci - “hotspots” - undergo meiotic DSBs at very high rates. Quantification of inter-homolog and inter-sister intermediates unique to crossover pathways, such as double Holliday Junctions, suggested that inter-sister events comprise ~20% of all joint molecules in budding yeast, and as much as 75% in fission yeast [4,7–10]. These rates translate to 8–25% of all sister-directed events, and 2.5–9% of all DSBs, resulting in SCEs (low and high estimates are calculated based on [8]). The higher rates compared to our analysis of SCEs in C. elegans could be explained by evolutionary divergence of repair pathways and their regulation, or as a consequence of the very “hot” hotspots that were analyzed, which do not represent the rest of the yeast genome (incidentally, C. elegans lacks strong meiotic hotpots [41,42]). Alternatively, the resolution of inter-sister repair intermediates may be heavily biased toward a noncrossover fate, so that SCEs in yeast meiosis are quite rare, as we find in worms.

The RecQ helicase BLMHIM−6 antagonizes meiotic SCEs

The scarcity of meiotic SCEs in worms could be explained by a complete lack of sister engagement by the crossover repair machinery, or by efficient destabilization of sister-directed crossover intermediates. RecQ helicases play multiple roles in meiosis and mitosis, including disassembling and dissolving of repair intermediates ([43–46]; reviewed in [47]), compelling us to assess the prevalence of meiotic SCEs in worms lacking the RecQ helicase BLMHIM−6 (designated as him-6 worms). While eliminating BLMHIM−6 does not affect homolog pairing or the formation of inter-homolog crossover precursors [43], meiotic SCEs were greatly elevated in him-6 animals (26/60 chromosomes; Figure 3A–B). The majority of SCEs likely result from meiotic events, since SCE levels were significantly lower in him-6 spo-11 worms that lack meiotic DSBs (6/49 chromosomes; Figure 3B–C). These residual SCEs likely reflect problems during DNA replication (Figure 3D), as was reported for RecQ deficiencies in worms and other systems ([48], reviewed in [47]). This analysis suggests that sister chromatids have the potential to engage in crossover repair, but that inter-sister repair intermediates are efficiently destabilized or dissolved by BLMHIM−6, explaining why so few SCEs form in meiosis. Since the rate of SCE formation is still limited in him-6 animals (<17% of DSBs repaired as SCEs, calculated as in Figure 2C), additional mechanisms might also act to prevent meiotic SCEs. One of these might be the pro-crossover activity of BLMHIM−6 itself [43]. Additional mechanisms are likely to be revealed by applying our assay to worms impaired in pathways implicated in sister-directed repair [40,49–52].

Figure 3: SCEs are elevated in worms lacking the RecQ helicase BLMHIM−6.

A. Multiple SCEs are visible in an immunofluorescence image of a bivalent from a him-6 worm. Note that each sister pair underwent an SCE. Red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU, Blue, DNA (DAPI). Interpretive diagram shown to the right. Scale bar = 1μm.

B. Elevated levels of meiotic SCEs in him-6 worms. Frequency of observed exchange chromatids in wild-type, him-6 and him-6 spo-11 worms. Note the much lower level of exchanges in him-6 spo-11 versus him-6 worms, indicating that most exchange events in him-6 animals result from meiotic DSBs. Exchange chromosomes in him-6 worms occured at a similar rate in both bivalents and univalents (22/46 and 4/14, respectively). Univalents are formed due to the failure of some inter-homolog crossover precursors to mature to chiasmata [43]. The pairwise comparisons between wild type and him-6 and between him-6 and him-6 spo-11 were significant (p<0.0001 and p<.00001, respectively; Pearson’s Chi-square test). N values indicate the number of chromatids counted. See also Table S1.

C. Mostly non-exchange univalents in a representative image of a him-6 spo-11 diakinesis nucleus. Arrowhead indicates the single exchange chromosome. The two X chromosomes (asteriks) are unlabeled due to their late replication. Red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU, Blue, DNA (DAPI). Scale bar = 1μm.

D. Premeiotic and meiotic SCE formation in EdU labeled chromatids would result in indistinguishable diakinesis bivalents. Schematics of chromatids undergoing DNA replication with EdU, followed by pre-meiotic DNA replication without EdU, and undergoing SCEs (red asterisks) in meiosis (top) or during premeiotic DNA replication (bottom). Premeiotic SCEs could also occur at times other than premeiotic DNA replication (not shown). See also Figure S4.

The Synaptonemal Complex promotes SCEs when it mislocalizes between sisters

Our observation that inter-sister crossovers are inhibited, directly or indirectly, by BLMHIM−6 raises the question of how inter-homolog crossovers are protected from BLMHIM−6 inhibition. Most inter-homolog crossovers are designated by an assemblage of pro-crossover factors - including COSA-1 and MutSƔ - that provide protection from disassembling activities [13,53]. The localization of these pro-crossover factors is directed by a conserved proteinaceous structure, the Synaptonemal Complex, that assembles exclusively at the interface between paired homologs [12,31,54,55].

In worms lacking the meiotic cohesin subunit REC-8, homologs mostly fail to pair and the Synaptonemal Complex is mislocalized to the inter-sister interface where it recruits pro-crossover factors [56,57]. These foci may represent inter-sister crossovers, suggesting that the Synaptonemal Complex can promote SCEs in rec-8 animals in an analogous fashion to the promotion of inter-homolog crossovers in wild-type animals. EdU labeling in rec-8 animals revealed elevated levels of SCEs (Figure 4A and 4D), with about half of the chromosomes harboring an exchange. While this rate is significantly higher than in control animals, this analysis is confounded by chromosome fragmentation, by the poor univalent morphology in rec-8 mutants, and by the inability to distinguish SCEs based on axis localization in this background (Figure 4A; [57]).

Figure 4: The Synaptonemal Complex promotes SCEs when it localizes between sister chromatids.

A. Many exchange chromatids in an immunofluorescence image of a diakinesis nuclei from a rec-8 animal. Purple, DNA (DAPI), green, EdU. Insets are explained in the interpretive diagrams above and below (boxed regions). Chromatids with crossovers are indicated by arrows. As observed previously [56,57,61], rec-8 mutants affect chromosome morphology in diakinesis, and precluded the use of an axis marker to highlight SCEs. Scale bar = 1μm.

B. Univalent chromosomes undergoing multiple SCEs in immunofluorescence images of syp-1K42E worms grown at 25°C. Red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU, Blue, DNA (DAPI). Insets are explained in the interpretive diagrams above and below (boxed regions). Top, diakinesis nucleus containing a univalent with two SCEs. Bottom, a diakinesis nucleus highlighting a univalent with no exchanges (asterisk) and a univalent with a single SCE (arrowhead). See also Figure S3. Scale bar = 1μm.

C. Univalent chromosomes undergoing an SCE in immunofluorescence images of syp-3(me42) worms. Red, axis (anti-HTP-3 antibodies); green, EdU, Blue, chromatin (DAPI). Interpretive diagram is shown above. The univalent on the left shows no SCEs, while the univalent on the right harbors an SCE (arrowhead). See also Figure S3. Scale bar = 1μm.

D. Elevated frequency of exchange univalents in syp-1K42E, syp-3(me42) and rec-8 worms. The unpaired X univalents in him-8 animals (from Figure 2A) are shown as controls. The percentages above the bars indicate the total number of exchange chromatids (p<0.01, for both pairwise comparisons to him-8, Pearson’s chi-square test; single and double SCEs were pooled together for statistical analysis). N values indicate the number of chromatids counted. See also Table S1.

E. A diagram illustrating Synaptonemal Complex localization between sisters in syp-1K42E, syp-3(me42) and rec-8 mutants, thereby promoting SCEs in an analogous way to the promotion of inter-homolog crossovers in wild-type animals. See also Figure S4.

We also observed elevated SCEs using orthogonal perturbations: mutations in Synaptonemal Complex components - syp-1K42E and syp-3(me42) - that mislocalize the Synaptonemal Complex to the interface between sister chromatids, but do not impede the ability of the Synaptonemal Complex to recruit pro-crossover factors such as COSA-1 (Figure 4B, Figure S3 and [58,59]). We found elevated levels of SCEs in both syp-1K42E and syp-3(me42) animals (Figure 4B–D), suggesting that pro-crossover factors now mark sites of future SCEs (Figure 4E). Further supporting this idea, we observed both single and double SCEs in syp-1K42E animals, consistent with the presence of multiple GFP-COSA-1 foci per chromosome in this mutant (an average of 16.4 foci/nucleus, or 1.37 foci/chromosome; [59]).

Our analysis of him-8 animals (Figure 2) indicates that the Synaptonemal Complex does not prevent SCE formation, either directly or indirectly by bringing the homologs together. If that were the case, SCEs would have been elevated on the X chromosomes in him-8 mutants, which are unpaired and not associated with the Synaptonemal Complex. We find, however, that the role of the Synaptonemal Complex in regulating crossovers extends beyond limiting the number of crossovers to exactly one per homolog pair [60]. It was previously shown that the Synaptonemal Complex promotes inter-homolog crossovers by recruitment of pro-crossover factors, thereby establishing a protective structure that prevents disassembly by helicases such as BLMHIM−6 [13,56,61]. Here we demonstrate that this idea also applies to inter-sister crossovers, which were likewise promoted by the Synaptonemal Complex when it is localized between the sisters (Figure 4). Our work suggests that during meiosis in worms almost all crossover repair is inhibited, except when promoted by factors associated with the Synaptonemal Complex. Hence, by virtue of its localization exclusively between homologous chromosomes, the Synaptonemal Complex promotes homolog-directed, rather than sister-directed, crossover repair (Figure S4).

Our results also suggest that BLMHIM−6 disassembles or dissolves repair intermediates that would otherwise mature to be SCEs, as was demonstrated for RecQ helicases in other systems ([47] and Figure S4). Interestingly, removal of BLMHIM−6 does not increase the number of inter-homolog crossovers [43]. We hypothesize that underlying this seeming discrepancy is differential resolution: both inter-sister and inter-homolog intermediates form in him-6 animals, but while inter-sister intermediates are resolved as both crossovers and noncrossovers, inter-homolog events preferentially yield noncrossovers. This idea is supported by the presence of transient inter-homolog associations in him-6 mutants that lack bona fide crossovers [43]. It further suggests that a homolog-specific structure - potentially the Synaptonemal Complex or the axis - helps to direct the resolution of repair intermediates.

Conclusions

Using the cytological assay we developed, we show that <2% of DSBs that undergo sister-directed repair form crossovers. In contrast, the formation of the one inter-homolog crossover necessary to direct accurate chromosome segregation is promoted by a very robust assurance pathway [15,16]. Our analysis suggests that the low rate of SCEs is brought about by a dual-acting mechanism that designates and protects the single inter-homolog crossover, and that inhibits almost all other inter-homolog and inter-sister crossovers. While sister-directed repair is mostly error-free, DNA repair that involves repetitive elements can result in deletions, insertions and karyotype rearrangements. This risk is higher during crossover repair, since the integrity of both the broken chromosome and the repair template are compromised. We speculate that the meiotic program in worms goes to great lengths to limit crossover repair in order to mitigate the risk incurred by imperfect exchanges.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Requests for further information, reagents, or resources should be directed to the lead contact, Ofer Rog (ofer.rog@utah.edu).

Materials Availability

Worms lines generated in this study will be available upon request or will be deposited to the Caenorhabditis Genetics center (CGC).

Data and Code Availability

The published article includes all datasets generated and analyzed during this study.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Unless otherwise noted, C. elegans worms were cultured at 20°C under standard conditions [63]. spo-11::aid(slc3), which degrades SPO-11 in the presence of auxin, was constructed using CRISPR/Cas9 RNP injection as described in [64], except without the 3xFLAG tag. Injection was performed into ieSi38 [Psun-1::TIR1::mRuby::sun-1 3’UTR, cb-unc-119(+)] him-8 (tm611) IV animals, resulting in linkage of all three elements. When grown on auxin, this strain is referred to in the text as him-8 spo-11(−) for simplicity. syp-1K42E(slc11) was obtained in a targeted mutagenesis screen that is described in [59]. syp-1K42E worms are temperature sensitive; they were maintained at 15°C, but were grown at 25°C prior to and during EdU labeling, causing the Synaptonemal Complex to localize to 12 unpaired homologs (Figure S3).

METHOD DETAILS

EdU incorporation:

Worms were synchronized through egg washing as in [65]. Age matched worms were grown to the young adult stage (12–16 hours post L4) and then washed with 1ml of PBS with 0.1% Triton X (v/v) into a conical tube. Animals were washed one additional time to remove excess bacteria, and transferred to a new tube to which EdU (ThermoFisher A10044) dissolved in water as a 10mM stock was added to a final concentration of 4mM. Animals were then transferred to a nutator set to 80rpm and soaked in EdU for 40 minutes at room temperature. Finally, animals were washed twice with PBS/Triton X and plated onto fresh NGM plates. Once dry, the plates were then transferred to the 25°C incubator to begin an approximately 28 hour chase. Chase times were highly sensitive to genetic background and growth conditions, and were empirically determined to maximize single-labeled chromatids in diakinesis. Notably, EdU labeling was done on animals younger than 24 hours post-L4, which may explain why the time to traverse the gonad and reach diakinesis was shorter than previously reported [15,21,22].

Cytology:

Cytology was performed as previously described in [66], with modifications to accommodate the click chemistry required for EdU visualization (ThermoFisher C10337). Briefly, samples were fixed, dissected, and labeled with primary and secondary antibodies as in [66]. Slides were then washed for 30 minutes at room temperature in PBS with 1% Triton X (v/v) for further permeabilization to allow for better penetration of the click chemistry reagents. Samples were then labeled with Alexa 488-azide according to the kit’s instructions for 30 minutes at room temperature. Samples were washed 3x times for 10 minutes and then DAPI stained for 20 minutes at room temperature. Slides were mounted using Prolong Glass (ThermoFisher P36980), cured overnight, and sealed with nail polish. In typical experiments, >95% of gonads exhibited bright EdU staining in meiotic prophase. The following antibodies were used: guinea-pig anti-HTP-3 (1:500, [67]), mouse anti-GFP (1:1000, Roche 11814460001), goat anti-SYP-1 (1:500, [68]), Cy3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Guinea pig (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch), Cy5 AffiniPure Donkey anti-Goat (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch), and Alexa488 AffiniPure Donkey anti-Mouse (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch).

Depletion of proteins using auxin:

NGM plates with a final concentration of 1μM auxin (indole-3-acetic acid, VWR AAA10556–36) were made according to [65]. P0 worms were grown until 24 hours post-L4 on standard NGM plates and then transferred to auxin plates to lay eggs. After 24 hours, the adult worms were removed and the F1 generation, whose full development occurred on auxin, was used as experimental animals.

Irradiation:

Worms were exposed to 5,000 rad (50 Gy) of X-ray irradiation using a W-(ISOTOPE) source, inducing an average of 7 DSBs per chromosome (14 per homolog pair). The number of DSBs generated per a given dose of radiation was empirically assessed by titrating low doses of radiation, as in [16], yielding a factor of 0.0028 DSBs per homolog pair per rad [59]. Irradiation was performed either 1 hour or 6 hours after EdU labeling, for mitotic and meiotic induced breaks, respectively. Dissections were completed as described above, 28 hours after EdU labeling. For meiotic irradiation experiments (Figure 2E), only nuclei with 7 DAPI staining bodies (5 bivalent autosomes and 2 X chromosome univalents) were considered for the analysis.

Image acquisition and processing:

Confocal Microscopy images were collected as z-stacks (at 0.2μm intervals) using a 63× 1.40 NA objective on a Zeiss LSM 880 microscope equipped with an AiryScan detector. Image processing and analysis was conducted using the ZEN software package (Blue 2.1). Partial maximum intensity projections are shown throughout.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Quantification of exchanges:

Exchanges between sisters were quantified at the diakinesis stage of meiotic prophase, where chromosomes are condensed and each sister chromatid is individualized. Depending on the presence or absence of a chiasma, the homologs condense in a bivalent cruciform structure or as two oval univalents, respectively (Figure 1B and 2B). Several factors contributed to asynchrony in obtaining single-labeled sister chromatids in diakinesis: asynchronous mitotic cell-cycle, late replication of the X chromosome [62], and semi-synchronous entry into, and passage through, meiosis [15,21,22]. In addition, the poor resolution in the z-axis prohibited analysis of chromosomes that were not oriented horizontally relative to the imaging plane. Exchanges (or lack thereof) were examined only in chromosomes where one of the two sisters was labeled with EdU and the two sisters were clearly distinguishable in the xy-plane. Sister exchanges were scored when EdU labeled chromatin crossed the chromosome axis (decorated with anti-HTP-3 antibodies), which represents the inter-sister interface. For bivalents, each of the long arms was scored independently. In rec-8 animals, the sisters were identified based on chromatin morphology. While it is hard to rule out that some distal exchanges were not scored due to the small amount of labeled chromatin traversing the axis, the distribution of SCEs along univalents and bilavents suggests that we successfully captured at least 80% of SCEs (Figure S2A).

Statistics:

Chi-squared statistical analysis was conducted using the R software package. For pairwise comparisons of SCE rates (Figures 2A, 3B and 4D), Pearson’s Chi Squared test was used. Our null hypothesis was that there is no change in SCE frequency, and a P value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant and sufficient to reject the null hypothesis. In Figure S2B, an unpaired Student’s t-test was used. Our null hypothesis was that there was no difference between the two categories (with and without EdU), and a p value smaller than 0.05 was considered sufficient to reject the null hypothesis. Significance is marked throughout the figures using three asterisks above significant comparisons. Confidence intervals shown in Figure 2C–E represent 95% exact binomial confidence intervals.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Guinea pig anti-HTP-3 | Yumi Kim Lab | N/A |

| Mouse anti-GFP | Roche | Cat#11814460001 |

| Goat anti-SYP-1 | Dernburg Lab | N/A |

| Cy3 AffinPure Donkey anti-Guinea pig | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#706-165-148 |

| Cy5 AffinPure Donkey anti-Goat | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#705-175-147 |

| 488 AffiniPure Donkey anti-Mouse | Jackson Immunoresearch | Cat#715-545-150 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Indole-3-acetic acid (auxin) | VWR | Cat#AAA10556-36 |

| Cas9 protein | IDT | |

| EdU | ThermoFisher | Cat#A10044 |

| Prolong Glass antifade agent | ThermoFisher | Cat#P36980 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Click-it EdU Cell Proliferation Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat#C10337 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans: N2 | CGC | N2 |

| him-8(tm611) IV | CGC | CA257 |

| unc-119(ed3) III; ieSi38 [Psun-1::TIR1::mRuby::sun-1 3’UTR, cb-unc-119(+)] IV | CGC | CA1199 |

| lig-4(ok716) III | CGC | RB873 |

| him-6(ok412) IV | CGC | VC193 |

| rec-8(ok978) IV/nT1 [qls51] (IV;V) | CGC | VC666 |

| him-6(ok412) spo-11(me44) IV/nT1 (IV;V) | CGC | TG2196 |

| meIs8 [pie-1p::GFP::cosa-1 + unc-119(+)] II | CGC | AV620 |

| GFP-cosa-1 II; meIs9[unc-119(+); pie-1promoter::gfp::SYP-3] | CGC | AV630 |

| syp-3(me42)/hT2 [bli-4(e937) let-?(q782) qIs48] (I;III) | CGC | AV276 |

| GFP-cosa-1 II; meIs9[unc-119(+); pie-1promoter::gfp::SYP-3]; syp-3(me42)/hT2 [bli-4(e937) let-?(q782) qIs48] (I;III) | This study | ROG306 |

| unc-119(ed3) III; ieSi38 [Psun-1::TIR1::mRuby::sun-1 3’UTR, cb-unc-119(+)] him-8(tm611) IV | This study | ROG125 |

| unc-119(ed3) III; ieSi38 [Psun-1::TIR1::mRuby::sun-1 3’UTR, cb-unc-119(+)] him-8(tm611) spo-11::aid (slc3) IV | This study | ROG130 |

| syp-1K42E(slc11) V | Described elsewhere (SGG and OR) | ROG198 |

| lig-4(ok717) III; him-8(tm611) IV | This study | ROG189 |

| meIs8 [pie-1p::GFP::cosa-1 + unc-119(+)] II; syp-1K42E(slc11) V | This study | ROG202 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Zen 2.3 Blue Edition | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | N/A |

| Zen 2.3 Black Edition | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | N/A |

| RStudio Version 1.1.463 | RStudio, INC | N/A |

| Other | ||

| W-(ISOTOPE) X-ray source | Golic Lab | N/A |

| LSM 880 confocal microscope with AiryScan | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | N/A |

Highlights.

New technique enables direct scoring of exchanges between sister chromatids

Exchanges between sister chromatids are rare during meiosis in C. elegans

Inactivating the RecQ helicase BLMHIM-6 increases the level of sister exchanges

The synaptonemal complex promotes exchanges when localized between sisters

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Rog Lab for their advice and for critical reading of this manuscript; Kent Golic for his feedback and for use of the X-ray source; Erik Toraason and Diana Libuda for sharing their manuscript and data prior to publication; Yuval Mazor, Yumi Kim, Keith Cheveralls, Ido Rog, Tess Stapleton, and Sarit Smolikove for comments; Sara Nakielny for comments on the manuscript and editorial work; and Yumi Kim and Abby Dernburg for antibodies. Worm strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was supported by a Genetics Training Grant 5T32GM007464-42 to DEA, and by a Pilot Project Award from the American Cancer Society, 1R35GM128804 grant from NIGMS, and start-up funds from the University of Utah to OR.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zickler D, and Kleckner N (2015). Recombination, pairing, and synapsis of homologs during meiosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haber JE, Thorburn PC, and Rogers D (1984). Meiotic and mitotic behavior of dicentric chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 106, 185–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadyk LC, and Hartwell LH (1992). Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132, 387–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwacha A, and Kleckner N (1994). Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKim KS, Green-Marroquin BL, Sekelsky JJ, Chin G, Steinberg C, Khodosh R, and Hawley RS (1998). Meiotic synapsis in the absence of recombination. Science 279, 876–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webber HA, Howard L, and Bickel SE (2004). The cohesion protein ORD is required for homologue bias during meiotic recombination. J. Cell Biol. 164, 819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cromie GA, Hyppa RW, Taylor AF, Zakharyevich K, Hunter N, and Smith GR (2006). Single Holliday junctions are intermediates of meiotic recombination. Cell 127, 1167–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldfarb T, and Lichten M (2010). Frequent and efficient use of the sister chromatid for DNA double-strand break repair during budding yeast meiosis. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyppa RW, and Smith GR (2010). Crossover invariance determined by partner choice for meiotic DNA break repair. Cell 142, 243–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KP, Weiner BM, Zhang L, Jordan A, Dekker J, and Kleckner N (2010). Sister Cohesion and Structural Axis Components Mediate Homolog Bias of Meiotic Recombination. Cell 143, 924–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan R, and McKee BD (2013). The Cohesion Protein SOLO Associates with SMC1 and Is Required for Synapsis, Recombination, Homolog Bias and Cohesion and Pairing of Centromeres in Drosophila Meiosis. PLoS Genet. 9. Available at: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page SL, and Hawley RS (2004). The genetics and molecular biology of the synaptonemal complex. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 525–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woglar A, and Villeneuve AM (2018). Dynamic Architecture of DNA Repair Complexes and the Synaptonemal Complex at Sites of Meiotic Recombination. Cell 173, 1678–1691.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mets DG, and Meyer BJ (2009). Condensins regulate meiotic DNA break distribution, thus crossover frequency, by controlling chromosome structure. Cell 139, 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosu S, Libuda DE, and Villeneuve AM (2011). Robust crossover assurance and regulated interhomolog access maintain meiotic crossover number. Science 334, 1286–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokoo R, Zawadzki KA, Nabeshima K, Drake M, Arur S, and Villeneuve AM (2012). COSA-1 Reveals Robust Homeostasis and Separable Licensing and Reinforcement Steps Governing Meiotic Crossovers. Cell 149, 75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JH (1958). Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Tritium-Labeled Chromosomes. Genetics 43, 515–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latt S. a. (1974). Sister chromatid exchanges, indices of human chromosome damage and repair: detection by fluorescence and induction by mitomycin C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 71, 3162–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claussin C, Porubský D, Spierings DC, Halsema N, Rentas S, Guryev V, Lansdorp PM, and Chang M (2017). Genome-wide mapping of sister chromatid exchange events in single yeast cells using Strand-seq. Elife 6. Available at: 10.7554/eLife.30560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tease C, and Jones GH (1979). Analysis of exchanges in differentially stained meiotic chromosomes of Locusta migratoria after BrdU-substitution and FPG staining. Chromosoma 73, 75–84. Available at: 10.1007/bf00294847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crittenden SL, and Kimble J (2008). Methods in Molecular Biology™. Methods Mol. Biol. 450, 27–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox PM, Vought VE, Hanazawa M, Lee M-H, Maine EM, and Schedl T (2011). Cyclin E and CDK-2 regulate proliferative cell fate and cell cycle progression in the C. elegans germline. Development 138, 2223–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breinbauer R, and Köhn M (2003). Azide-alkyne coupling: a powerful reaction for bioconjugate chemistry. Chembiochem 4, 1147–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gratzner HG (1982). Monoclonal antibody to 5-bromo- and 5-iododeoxyuridine: A new reagent for detection of DNA replication. Science 218, 474 LP–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodyer W, Kaitna S, Couteau F, Ward JD, Boulton SJ, and Zetka M (2008). HTP-3 Links DSB Formation with Homolog Pairing and Crossing Over during C. elegans Meiosis. Dev. Cell 14, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dumont J, Oegema K, and Desai A (2010). A kinetochore-independent mechanism drives anaphase chromosome separation during acentrosomal meiosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muscat CC, Torre-Santiago KM, Tran MV, Powers JA, and Wignall SM (2015). Kinetochore-independent chromosome segregation driven by lateral microtubule bundles. Elife 4, e06462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dernburg AF, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, and Villeneuve AM (1998). Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell 94, 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutiérrez C, and Calvo A (1981). Approximation of baseline and BrdU-induced SCE frequencies. Chromosoma 83, 685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heartlein MW, O’Neill JP, and Preston RJ (1983). SCE induction is proportional to substitution in DNA for thymidine by CldU and BrdU. Mutat. Res 107, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacQueen AJ, Phillips CM, Bhalla N, Weiser P, Villeneuve AM, and Dernburg AF (2005). Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell 123, 1037–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert VJ, Davis MW, Jorgensen EM, and Bessereau J-L (2008). Gene conversion and end-joining-repair double-strand breaks in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 180, 673–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Y, and Smolikove S (2013). Impaired resection of meiotic double-strand breaks channels repair to nonhomologous end joining in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol 33, 2732–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macaisne N, Kessler Z, and Yanowitz JL (2018). Meiotic Double-Strand Break Proteins Influence Repair Pathway Utilization. Genetics 210, 843–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae W, Hong S, Park MS, Jeong H-K, Lee M-H, and Koo H-S (2019). Single-strand annealing mediates the conservative repair of double-strand DNA breaks in homologous recombination-defective germ cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Repair 75, 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clejan I, Boerckel J, and Ahmed S (2006). Developmental modulation of nonhomologous end joining in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 173, 1301–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colaiácovo MP, MacQueen AJ, Martinez-Perez E, McDonald K, Adamo A, La Volpe A, and Villeneuve AM (2003). Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev. Cell 5, 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamper EL, Rodenbusch SE, Rosu S, Ahringer J, Villeneuve AM, and Dernburg AF (2013). Identification of DSB-1, a protein required for initiation of meiotic recombination in Caenorhabditis elegans, illuminates a crossover assurance checkpoint. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosu S, Zawadzki KA, Stamper EL, Libuda DE, Reese AL, Dernburg AF, and Villeneuve AM (2013). The C. elegans DSB-2 Protein Reveals a Regulatory Network that Controls Competence for Meiotic DSB Formation and Promotes Crossover Assurance. PLoS Genet. 9. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1003674&type=printable. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toraason E, Clark C, Horacek A, Glover ML, Salagean A, and Libuda DE (2020). Sister chromatid repair maintains genomic integrity during meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. 2020.07.22.216143. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.22.216143v2 [Accessed September 29, 2020].

- 41.Kaur T, and Rockman MV (2014). Crossover heterogeneity in the absence of hotspots in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 196, 137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Z, Kim Y, and Dernburg AF (2016). Meiotic recombination and the crossover assurance checkpoint in Caenorhabditis elegans. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 54, 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schvarzstein M, Pattabiraman D, Libuda DE, Ramadugu A, Tam A, Martinez-Perez E, Roelens B, Zawadzki KA, Yokoo R, Rosu S, et al. (2014). DNA helicase HIM-6/BLM both promotes MutSγ-dependent crossovers and antagonizes MutSγ-independent interhomolog associations during caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. Genetics 198, 193–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Muyt A, Jessop L, Kolar E, Sourirajan A, Chen J, Dayani Y, and Lichten M (2012). BLM helicase ortholog Sgs1 is a central regulator of meiotic recombination intermediate metabolism. Mol. Cell 46, 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh SD, Lao JP, Hwang PY-H, Taylor AF, Smith GR, and Hunter N (2007). BLM ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell 130, 259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holloway JK, Morelli MA, Borst PL, and Cohen PE (2010). Mammalian BLM helicase is critical for integrating multiple pathways of meiotic recombination. J. Cell Biol. 188, 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatkevich T, and Sekelsky J (2017). Bloom syndrome helicase in meiosis: Pro-crossover functions of an anti-crossover protein. Bioessays 39, 1700073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wicky C, Alpi A, Passannante M, Rose A, Gartner A, and Müller F (2004). Multiple genetic pathways involving the Caenorhabditis elegans Bloom’s syndrome genes him-6, rad-51, and top-3 are needed to maintain genome stability in the germ line. Mol. Cell. Biol 24, 5016–5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adamo A, Montemauri P, Silva N, Ward JD, Boulton SJ, and La Volpe A (2008). BRC-1 acts in the inter-sister pathway of meiotic double-strand break repair. EMBO Rep. 9, 287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barber LJ, Youds JL, Ward JD, McIlwraith MJ, O’Neil NJ, Petalcorin MIR, Martin JS, Collis SJ, Cantor SB, Auclair M, et al. (2008). RTEL1 Maintains Genomic Stability by Suppressing Homologous Recombination. Cell 135, 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bickel JS, Chen L, Hayward J, Yeap SL, Alkers AE, and Chan RC (2010). Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes (SMC) Proteins Promote Homolog-Independent Recombination Repair in Meiosis Crucial for Germ Cell Genomic Stability. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Muse T, Galindo-Diaz U, Garcia-Rubio M, Martin JS, Polanowska J, O’Reilly N, Aguilera A, and Boulton SJ (2019). A Meiotic Checkpoint Alters Repair Partner Bias to Permit Inter-sister Repair of Persistent DSBs. Cell Rep. 26, 775–787.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zickler D, and Kleckner N (2016). A few of our favorite things: Pairing, the bouquet, crossover interference and evolution of meiosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 54, 135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacQueen AJ, Colaiácovo MP, McDonald K, and Villeneuve AM (2002). Synapsis-dependent and -independent mechanisms stabilize homolog pairingduring meiotic prophase in C.elegans. Genes Dev. 16, 2428–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rog O, Köhler S, and Dernburg AF (2017). The synaptonemal complex has liquid crystalline properties and spatially regulates meiotic recombination factors. Elife 6, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cahoon CK, Helm JM, and Libuda DE (2019). Synaptonemal Complex Central Region Proteins Promote Localization of Pro-crossover Factors to Recombination Events During Caenorhabditis elegans Meiosis. Genetics 213, 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pasierbek P, Jantsch M, Melcher M, Schleiffer A, Schweizer D, and Loidl J (2001). A Caenorhabditis elegans cohesion protein with functions in meiotic chromosome pairing and disjunction. Genes Dev. 15, 1349–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smolikov S, Eizinger A, Schild-Prufert K, Hurlburt A, McDonald K, Engebrecht J, Villeneuve AM, and Colaiácovo MP (2007). SYP-3 restricts synaptonemal complex assembly to bridge paired chromosome axes during meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 176, 2015–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gordon SG, Kursel LE, Xu K, and Rog O (2020). Synaptonemal Complex dimerization regulates chromosome alignment and crossover patterning in meiosis. 2020.09.24.310540. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.24.310540v1 [Accessed September 29, 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Libuda DE, Uzawa S, Meyer BJ, and Villeneuve AM (2013). Meiotic chromosome structures constrain and respond to designation of crossover sites. Nature 502, 703–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crawley O, Barroso C, Testori S, Ferrandiz N, Silva N, Castellano-Pozo M, Jaso-Tamame AL, and Martinez-Perez E (2016). Cohesin-interacting protein WAPL-1 regulates meiotic chromosome structure and cohesion by antagonizing specific cohesin complexes. Elife 5, e10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jaramillo-Lambert A, Ellefson M, Villeneuve AM, and Engebrecht J (2007). Differential timing of S phases, X chromosome replication, and meiotic prophase in the C. elegans germ line. Dev. Biol 308, 206–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brenner S (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang L, Köhler S, Rillo-Bohn R, and Dernburg AF (2018). A compartmentalized signaling network mediates crossover control in meiosis. Elife 7. Available at: 10.7554/eLife.30789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang L, Ward JD, Cheng Z, and Dernburg AF (2015). The auxin-inducible degradation (AID) system enables versatile conditional protein depletion in C. elegans. Development 142, 4374–4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips CM, Meng X, Zhang L, Chretien JH, Urnov FD, and Dernburg AF (2009). Identification of chromosome sequence motifs that mediate meiotic pairing and synapsis in C. elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 934–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hurlock ME, Čavka I, Kursel LE, Haversat J, Wooten M, Nizami Z, Turniansky R, Hoess P, Ries J, Gall JG, et al. (2020). Identification of novel synaptonemal complex components in C. elegans. J. Cell Biol. 219. Available at: 10.1083/jcb.201910043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harper NC, Rillo R, Jover-Gil S, Assaf ZJ, Bhalla N, and Dernburg AF (2011). Pairing centers recruit a Polo-like kinase to orchestrate meiotic chromosome dynamics in C. elegans. Dev. Cell 21, 934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all datasets generated and analyzed during this study.