Abstract

Background:

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) carries a poor prognosis. Liver transplantation (LT) is potentially curative for localized HCC. We evaluated the impact of LT on US general population HCC-specific mortality rates.

Methods:

The Transplant Cancer Match Study links the US transplant registry with 17 cancer registries. We calculated age-standardized incidence (1987–2017) and incidence-based mortality (IBM) rates (1991–2017) for adult HCCs. We partitioned population-level IBM rates by cancer stage and calculated counterfactual IBM rates assuming transplanted cases had not received a transplant.

Results:

Among 129,487 HCC cases, 45.9% had localized cancer. HCC incidence increased on average 4.0% annually (95%CI=3.6%−4.5%). IBM also increased for HCC overall (2.9% annually; 95%CI=1.7%−4.2%) and specifically for localized stage HCC (4.8% annually; 95%CI=4.0%−5.5%). The proportion of HCC-related transplants jumped sharply from 6.7% (2001) to 18.0% (2002), and further increased to 40.0% (2017). HCC-specific mortality declined among both non-transplanted and transplanted cases over time. In the absence of transplants, IBM for localized HCC would have increased at 5.3% instead of 4.8% annually.

Conclusions:

LT has provided survival benefit to patients with localized HCC. However, diagnosis of many cases at advanced stages, limited availability of donor livers, and improved mortality for non-transplanted patients have limited the impact of transplantation on general population HCC-specific mortality rates.

Impact:

Though LT rates continue to rise, better screening and treatment modalities are needed to halt the rising HCC mortality rates in the US.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Liver transplantation, epidemiology, incidence-based mortality, liver cancer, trends

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer and the fourth-most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in the world.(1) Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have contributed to rising HCC incidence in the United States (US).(2–4) Though HCC carries a poor prognosis, early detection of tumors through surveillance of at-risk individuals and treatment advances have improved survival.(4)

Liver transplantation (LT) offers definitive treatment for patients with localized HCC, because it removes the tumor and addresses underlying cirrhosis. LT is associated with 5-year survival rates of up to 70% for patients with localized HCC who fulfill the “Milan criteria” (i.e., one lesion <5 cm in diameter or up to 3 lesions <3 cm each, without evidence of vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread).(5,6)

In 2002, the US transplantation network implemented a liver allocation program that utilized the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) to ensure equitable organ distribution based on the urgency for LT.(7) To facilitate transplantation of HCC patients before their tumors progressed, the allocation system awarded exception points to patients who fulfilled the Milan criteria.(5,7,8) After implementation of MELD-based allocation, HCC patients experienced decreased waitlist time, increased transplantation rates, and improved survival.(9) Recently, organ allocation policies have evolved further to provide less priority to HCC patients for LT, with the goal to achieve greater equity in allocation of donor livers among transplant candidates with or without HCC.(10)

Cancer mortality rates are an important measure of progress against cancer because they capture both cancer incidence and survival,(11) but the effects of LT on population-level HCC mortality rates have not been assessed. The impact may be limited, because LT is only offered to a subset of HCC patients with localized cancer. Indeed, analyses of data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries have shown a steady increase in general population mortality rates for HCC in the US.(2,12) However, population-level cancer mortality data are obtained from death certificates which lack information on cancer characteristics such as stage at diagnosis or treatment. In contrast, incidence-based mortality (IBM) analysis, which incorporates linked data on mortality and incident cancers, enables decomposition of general population mortality rates according to cancer attributes.(11)

Herein, we present a comprehensive analysis of HCC incidence and IBM rates using US cancer registry data. We partition general population HCC mortality by cancer stage at diagnosis and use linked data from the US solid organ transplant registry to identify HCC cases who received LT. Our study thus provides information on the temporal trends in HCC in the US general population and the impact of LT on mortality rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

The Transplant Cancer Match (TCM) Study links the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) with 18 population‐based cancer registries, providing cancer data for approximately 50% of solid organ transplants in the US based on geographic area of residence.(13) SRTR contains information on all solid organ transplants (1987 onwards), including demographics, transplanted organs, and indication for transplant. As described below, we utilized data on HCC cases diagnosed during 1987–2017 in the geographic areas covered by 12 TCM cancer registries that provided causes of death for deceased cases, which are essential for calculating IBM rates (Table 1). This study was approved by human subjects’ review committees at the National Cancer Institute and, as required, at participating cancer registries.

Table 1:

Characteristics of HCC cases in 12 US states (1987 – 2017)

| Characteristics | Total (N = 129,487) Number (%) |

Non-transplanted cases (N = 114,754) Number (%) |

Transplanted casesa (N = 14,733) Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||

| 18–29 | 890 (0.7) | 803 (0.7) | 87 (0.6) |

| 30–39 | 2,079 (1.6) | 1,834 (1.6) | 245 (1.7) |

| 40–49 | 12,259 (9.5) | 10,170 (8.9) | 2,089 (14.2) |

| 50–59 | 37,951 (29.3) | 31,005 (27.0) | 6,946 (47.2) |

| 60–69 | 37,343 (28.8) | 32,502 (28.3) | 4,841 (32.9) |

| 70+ | 38,965 (30.1) | 38,440 (33.5) | 525 (3.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 97,637 (75.4) | 86,322 (75.2) | 11,315 (76.8) |

| Female | 31,850 (24.6) | 28,432 (24.8) | 3,418 (23.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 65,435 (50.5) | 56,781 (49.5) | 8,654 (58.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17,683 (13.7) | 16,417 (14.3) | 1.266 (8.6) |

| Asian | 16,515 (12.8) | 14,957 (13.0) | 1,558 (10.6) |

| Hispanic | 28,748 (22.2) | 25,646 (22.4) | 3,102 (21.1) |

| Other/unknown | 1,106 (0.8) | 953 (0.8) | 153 (1.0) |

| Cancer stage at diagnosisb | |||

| Local | 59,431 (45.9) | 44,698 (39.0) | 14,733 (100.0) |

| Regional | 27,308 (21.1) | 27,308 (21.1) | 0 |

| Distant | 24,108 (18.6) | 24,108 (18.6) | 0 |

| Unstaged | 18,640 (14.4) | 18,640 (14.4) | 0 |

| Cancer registry (years of cancer diagnoses) | |||

| California (1988–2012) | 34,499 (26.6) | 30,844 (26.9) | 3,655 (24.8) |

| Colorado (1988–2014) | 3,481 (2.7) | 3,068 (2.7) | 413 (2.8) |

| Connecticut (1987–2009) | 2,199 (1.7) | 2,012 (1.8) | 187 (1.3) |

| Georgia (1995–2010) | 3,628 (2.8) | 3,214 (2.8) | 414 (2.8) |

| Iowa (1987–2009) | 1,355 (1.0) | 1,208 (1.1) | 147 (1.0) |

| Illinois (1987–2013) | 9,908 (7.7) | 8,571 (7.5) | 1,337 (9.1) |

| Kentucky (1995–2011) | 1,845 (1.4) | 1,586 (1.4) | 259 (1.8) |

| New Jersey (1987–2016) | 9,185 (7.1) | 8,202 (7.1) | 983 (6.7) |

| New York (1995–2017) | 23,269 (18.0) | 20,747 (18.1) | 2,522 (17.1) |

| Ohio (1996–2015) | 7,101 (5.5) | 6,225 (5.4) | 876 (6.0) |

| Pennsylvania (1987–2013) | 11,132 (8.6) | 9,608 (8.4) | 1,524 (10.3) |

| Texas (1995–2014) | 21,885 (16.9) | 19,469 (17.0) | 2,416 (16.4) |

Received transplant within 5 years of diagnosis.

These values represent the updated stage classification after cases with advanced stage indicated in the cancer registry (1,847 regional, 267 distant, and 522 unstaged cancers) were reclassified as having local stage HCC because the patient received a liver transplant.

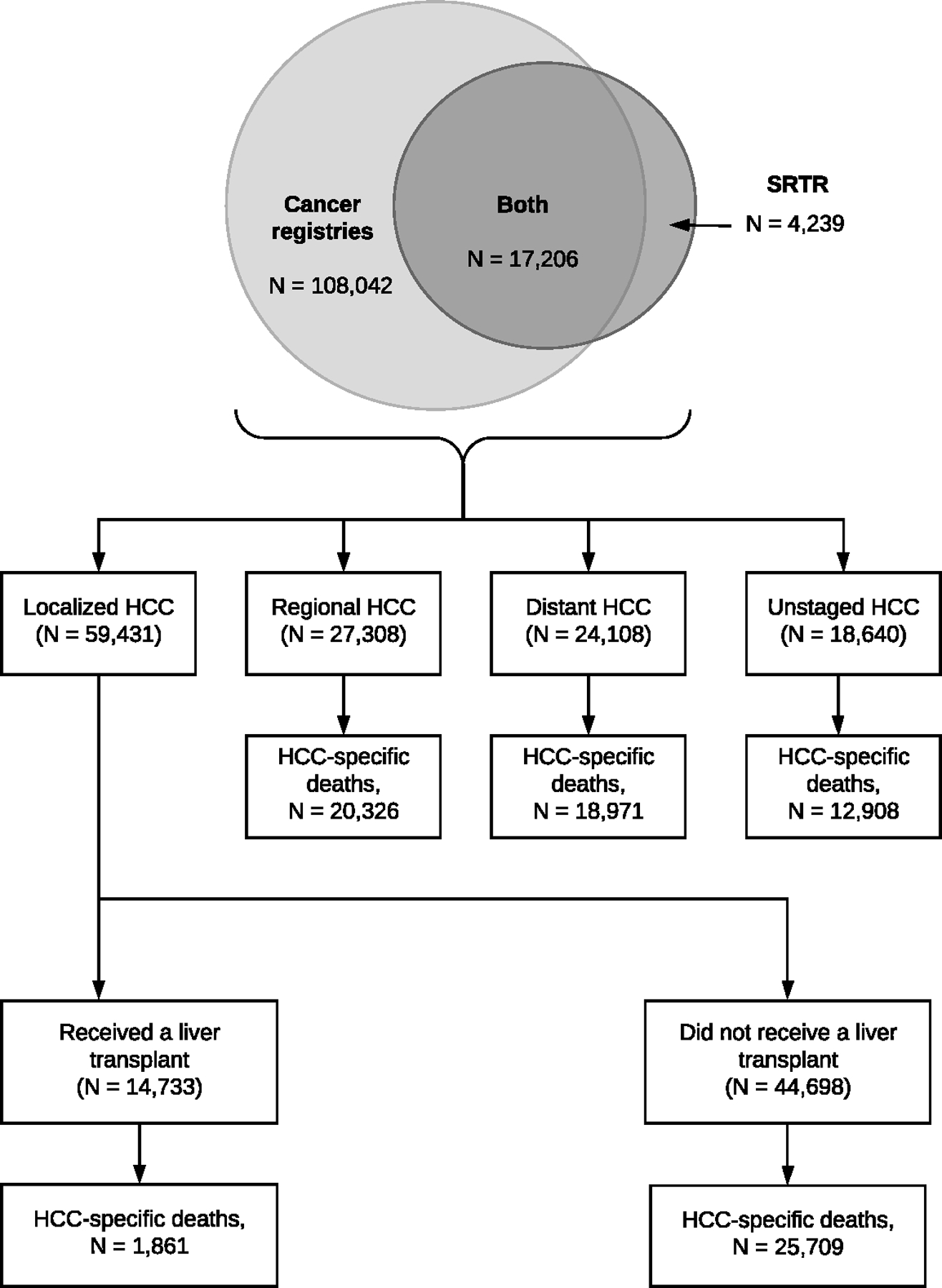

HCC cases and causes of death

We included HCC cases among adults (age ≥18 years at diagnosis) from both participating cancer registries and SRTR. From cancer registries, first primary HCC cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology version-3 codes (topography C22.0, morphology 8170–8175). We excluded cases diagnosed only by death certificate. In SRTR, adult transplant candidates or recipients were considered to have HCC if they linked to an HCC record in a cancer registry, had a candidate or recipient HCC diagnosis, or received MELD exception points for HCC. We ascertained a total of 129,487 HCC cases from cancer registries and SRTR (Figure 1). Of these, 108,042 (83.4%) cases were reported in cancer registries only, 4,239 (3.3%) cases were reported in SRTR only, and 17,206 (13.3%) cases were reported in both cancer registries and SRTR.

Figure 1: Characteristics of the study population.

The flow chart describes the characteristics of the 129,487 HCC cases from 12 states participating in the Transplant Cancer Match Study (1987–2017): 108,042 (83.4%) cases that were captured by cancer registries but were not registered in the SRTR (i.e., not entered on the waitlist or transplanted), 17,206 (13.3%) cases that were present in both cancer registries and the SRTR (i.e., entered on the waitlist and/or transplanted), and 4,239 (3.3%) cases that were on the waitlist or received a transplant but were not captured by the cancer registries. These cases were then further classified by the cancer stage at diagnosis as localized (confined to the liver), regional (involvement of regional lymph nodes), distant (metastasized), or unstaged. We reclassified some transplant recipients who had regional (N=1,847), distant (N=267), or unstaged (N=522) HCCs, as recorded by cancer registries, to localized stage, as the advanced stages may have been miscoded due to progression between diagnosis and transplantation. Localized HCCs were classified according to their transplant status. The number of HCC-specific deaths (1991–2017) for each stage are also specified.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

We classified HCC stage for cancer registry cases as localized, regional, distant, or unstaged using the SEER historic stage variable (Figure 1).(14) Cases identified only through SRTR or that linked to the SRTR were classified as localized HCCs because LT is only offered to patients with localized cancer (2,636 HCC cases [2.0% of cancer registry cases] had stage reclassified).(5,15)

Since most HCCs were documented in cancer registries, we primarily used underlying causes of death ascertained by cancer registries from the National Center for Health Statistics. For SRTR-only cases, causes of death were obtained from information reported by transplant centers. Because causes of death may be misclassified in death certificates, we used a SEER algorithm to categorize deaths as HCC-specific (Supplementary Table 1).(16,17) This algorithm utilizes data on tumor sequence (i.e., only one tumor, or the first of multiple tumors), site of cancer diagnosis, and cause of death including site-related co-morbidities (e.g., liver cirrhosis). If HCC was the only cancer diagnosed in an individual, then deaths due to any cancer or gastrointestinal disease were considered HCC-specific deaths. If HCC was the first of multiple cancers diagnosed in an individual, then deaths due to cancers of liver, intrahepatic bile ducts, or ill-defined primary sites, or gastrointestinal disease were considered HCC-specific. Using a broad range of causes of death improves the accuracy of cause-specific death classification.(16)

Statistical analysis

IBM rates correspond to general population mortality rates in which the numerator is the number of HCC-specific deaths linked to a prior HCC diagnosis, and the denominator is the person-time in the general population.(11) Since IBM rates rely on this linkage, sufficient “burn-in” period after cancer diagnosis is needed to capture all deaths due to the cancer. We utilized a 5-year burn-in period because the 5-year cumulative probability of death following HCC diagnosis is 94.9% (2). Thus, the IBM rate of localized HCC in 1991 equals the number of deaths due to HCC in 1991 among people diagnosed with localized HCC during 1987–1991, divided by the corresponding population in the geographic areas contributing to deaths during 1991. Since we used a 5-year burn in period, IBM rates were calculated for 1991–2017. Age-adjusted rates were standardized to the 2000 US general population. We present IBM rates partitioned by HCC stage at diagnosis. We used the Joinpoint regression program (version 4.6.0.0) to detect significant changes in calendar year trends in age-standardized incidence and IBM rates. Joinpoint regression identifies calendar years (i.e., joinpoints) where the slope of the log-linear segments changes significantly and calculates the annual percentage change in the rates between two consecutive joinpoints. A Monte Carlo permutation method was used to identify statistically significant changes in trends at a threshold of p<0.05. (18,19)

We used a counterfactual method to evaluate the impact of LT on general population HCC mortality rates. Specifically, we calculated HCC-specific mortality rates for cases with localized cancer who did not receive a transplant and applied these rates to the person-time observed following LT, stratified by diagnosis year and time-updated age group and calendar year. This calculation yielded the number of deaths that would have occurred among localized HCC cases who received LT if they had not received those transplants. We then used these numbers to calculate the counterfactual age-adjusted IBM rates in the absence of transplant according to calendar year of death.

Finally, we calculated HCC-specific mortality rates restricted to localized HCC cases by transplant status and calendar year of diagnosis. For non-transplanted cases, follow-up began at diagnosis and ended at death, last follow-up, or 5 years after diagnosis, whichever was earlier. For transplanted cases, we divided up their person-time so that follow-up before LT was considered non-transplanted, while person-time beginning at LT and ending at the earlier of death, last follow-up, or 5 years after diagnosis was considered transplanted. The resulting mortality rates were age-standardized to the person-time of follow-up among the transplanted HCC cases. Because participating cancer registries provided data for different calendar periods, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which we derived estimates separately for each individual cancer registry region.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of HCC cases in 12 US states (N=129,487) are provided in Table 1, according to LT status. Cases were mostly older than 50 years at diagnosis (88.2%). Approximately 46% of cases (N=59,431) had localized stage, of whom 14,733 (24.8%, or 11.4% of all HCCs) received LT (Figure 1). Transplanted cases were younger (median age at diagnosis 57 vs. 63 years) and more likely to be male (76.8% vs. 75.2%) and non-Hispanic white (58.7% vs. 49.5%) than non-transplanted cases (Table 1).

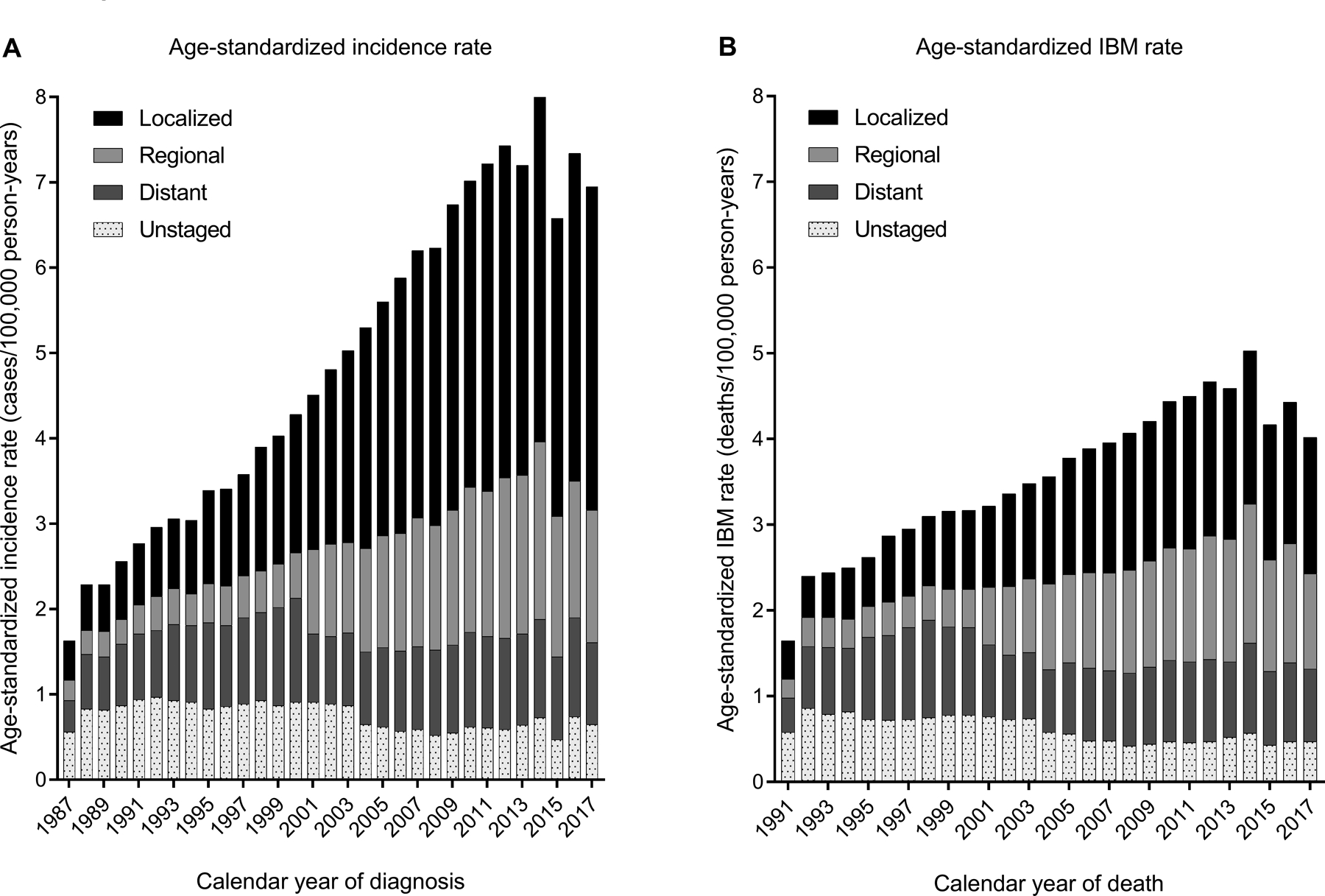

Overall, HCC incidence increased between 1987 and 2017 at an average rate of 4.0% per year (95% confidence intervals [CI]=3.6%−4.5%) (Figure 2A). The increase was steepest during 1987–2011 (APC, 5.2%), when incidence increased from 1.6 per 100,000 person-years (1987) to 7.2 per 100,000 person-years (2011), following which there was a non-significant decline. This trend was largely driven by localized HCC, which increased on average 10.2% per year during 1987–2006 and 5.0% per year during 2006–2011. The proportion of HCC cases that were local stage increased from 27.8% in 1987 to 54.3% in 2017.

Figure 2: Incidence and IBM rates of HCC, overall and partitioned by cancer stage at diagnosis.

The figures present the age-standardized rates (2000 US population) for HCC incidence (panel A) and IBM (panel B) according to calendar year of diagnosis or death in the 12 participating US states (1987–2017) The height of each bar represents the overall incidence or IBM rate for a specific calendar year. Each bar is partitioned to represent rates contributed by localized, regional, distant, or unstaged HCCs.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IBM, incidence-based mortality

During 1991–2017 in these states, a total of 79,775 HCC-specific deaths were observed following an HCC diagnosis (Figure 1). Of these, 27,570 (34.6%) deaths were in people with localized stage, 20,326 (25.5%) were in people with regional stage, and 18,971 (23.8%) were in people with distant stage HCC. For localized HCCs, most deaths (N=25,709; 93.2%) occurred in non-transplanted people.

Overall, IBM increased on average 2.9% per year (95%CI=1.7%−4.2%) (Figure 2B). The increase was apparent during 1991–2014, when IBM rose from 1.7 to 5.0 per 100,000 person-years, after which there was a non-significant decline. Increasing IBM rates were specifically observed for localized stage (APC, 4.8%) (Figure 2B).

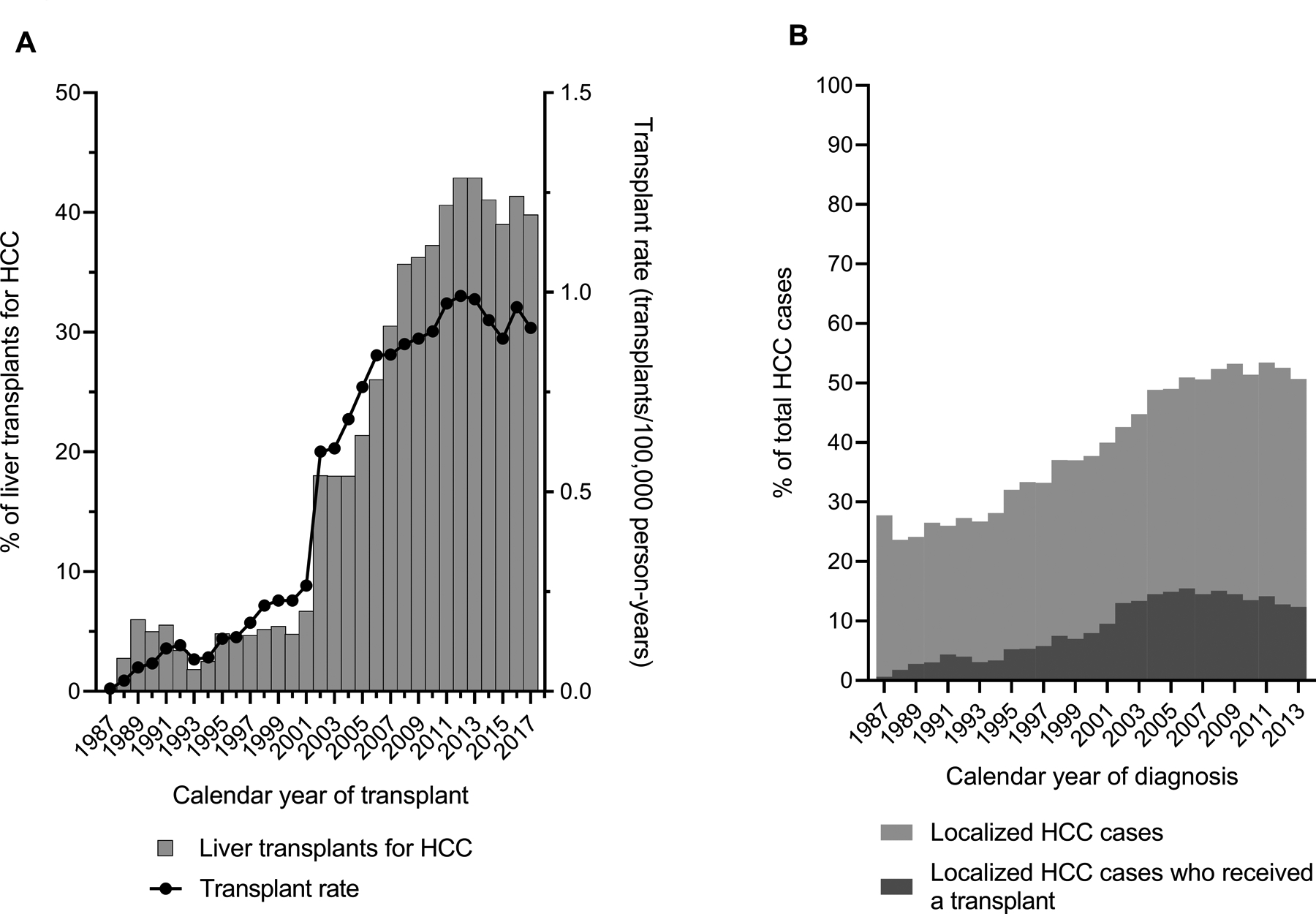

HCC-related LT rates increased steeply over time, particularly between 2000–2003 (APC, 40.9%) (Figure 3A). In 1987, 1.0% of all adult LT was conducted for HCC. This proportion increased gradually to 6.7% in 2001, jumped sharply to 18.0% in 2002 when MELD exception points were introduced, further increased to 40.0% in 2011, and remained stable thereafter (Figure 3A). The proportion of all HCC cases who received a transplant within 5 years of diagnosis varied over time from 0.6% in 1987, gradually increasing to a peak of 15.5% in 2006, and then declining to 12.4% in 2013 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: Liver transplants in the 12 US states participating in the study.

Panel A, shows the proportion of total adult liver transplants that were conducted for HCC in the 12 participating US states (left y-axis) and the rate of HCC-related transplants (number of transplants divided by the general population; right y-axis) by calendar year of transplant (x-axis). Panel B shows the proportion of total HCC cases that were local stage, and the proportion of total HCC cases who received a transplant within 5 years of diagnosis (y-axis) by calendar year of diagnosis (x-axis). Data are shown for cases diagnosed during 1987–2013 to include transplants through 2017.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma

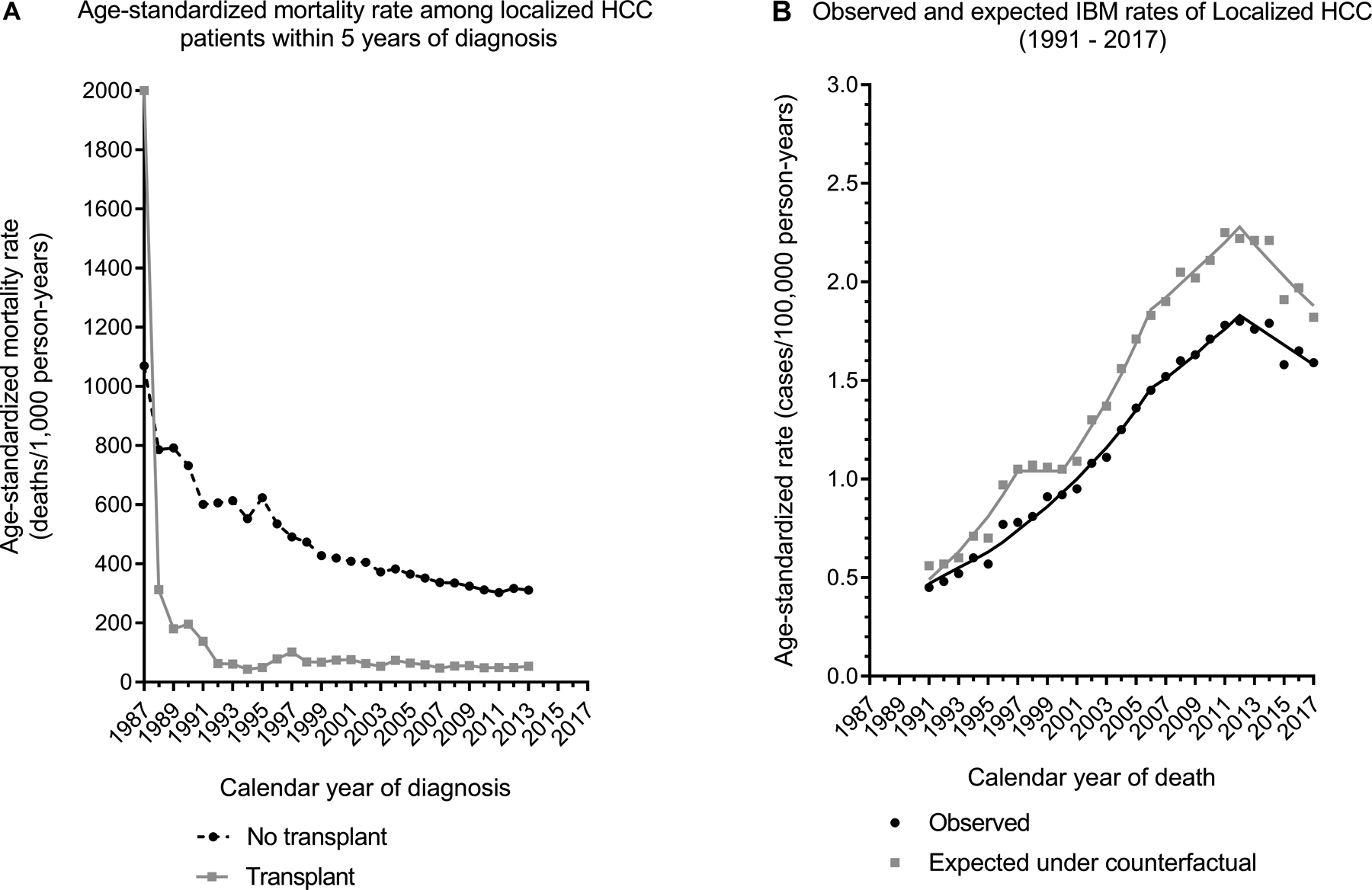

HCC-specific mortality rates among localized HCC cases declined across calendar years of diagnosis for both people who did and those who did not receive LT, although they remained higher for non-transplanted than transplanted cases (Figure 4A). In the absence of transplantation for localized HCCs, IBM rates would have increased at 5.3% per year instead of 4.8% per year for local stage HCC (Figure 4B). The impact of LT appeared greatest during 2002–2013 when the counterfactual IBM rate for localized HCC was 20.4–25.6% higher than the observed rate in each calendar year.

Figure 4: Impact of liver transplants on HCC-specific mortality in the 12 US states participating in the study.

Panel A shows the age-standardized mortality rate within 5 years of diagnosis among localized HCC cases (on y-axis) by calendar year of diagnosis (x-axis), according to their transplant status. Data has been shown for calendar years 1987–2013 to include deaths that have occurred till 2017. Panel B presents the observed (solid line) and counterfactual (dotted line) IBM rates for localized HCCs by calendar year of death.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IBM, incidence-based mortality

Additional details regarding HCC incidence, IBM, and LT trends are provided in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1. In our sensitivity analysis, the patterns were similar for each registry included in the study, although some data were sparse.

DISCUSSION

During 1987–2017, HCC has been a rising cause of cancer morbidity and mortality in the US, as demonstrated by the increasing incidence and IBM rates that we observed. The increase in incidence was steepest for localized HCC, resulting in a stage shift that likely reflects improvements in early detection. Additionally, implementation of MELD-based allocation for LT, which includes exception points for HCC, caused a sharp increase in LT for HCC in 2002. Transplantation has reduced HCC mortality rates in the general population. However, since only a small proportion of HCC patients eventually underwent LT, and because mortality rates improved in non-transplanted patients, the impact on population-level mortality rates has been somewhat limited.

Cancer mortality rates can be calculated in different ways depending on the denominator. One method is to calculate deaths among people diagnosed with cancer, which is mostly a function of cancer survival. In contrast, the denominator for IBM rates is the general population in a specified geographic area, i.e., the area covered by the included cancer registries for specific calendar years.(11) Moreover, IBM links cancer deaths to incident cancer diagnosis data, which provides information on cancer stage and treatment.(11) General population HCC-specific mortality rates have been increasing at the highest rates of all cancer sites in the US,(3) and our IBM analyses reveal that much of this increase over time has been related to deaths among patients with localized or regional cancers. IBM rates reflect general population mortality and are thus a function of both cancer incidence and survival. Increases in IBM for localized HCC in our study partly reflect an increase in incidence, but our observation that IBM rates for localized HCC are not increasing as steeply as the incidence rates is likely attributable to improved survival over time for localized HCC.

Forecasts using SEER data have predicted that HCC incidence will increase in the next 15 years due to aging of the baby boomer generation (born during 1945–1965) and rising rates of NAFLD.(20) Moreover, etiology of HCC differs across racial/ethnic groups, with NAFLD-related cases seen more frequently in Hispanics.(21) The introduction of direct-acting antiviral therapy in 2013 has dramatically improved cure rates for HCV infection, which should eventually lead to a decline in HCV-associated HCC incidence. Of interest, our data and the most recent analysis of SEER data suggest that the incidence rates of HCC have stabilized following 2011–2013,(22) although it is likely too early to capture the effect of HCV treatment or be confident about this favorable trend. HCV and NAFLD are the most common causes of HCC-related transplants in the US.(23,24) Significant racial disparities exist in access to liver transplantation.(25) As NAFLD-associated HCC cases rise in the US, racial disparity in access to transplant for Hispanics may widen even further.

Only a subset of patients with localized HCCs are eligible for LT. With careful candidate selection for patients whose tumors fulfil the Milan criteria, LT is associated with a low 5-year recurrence rate of 11–18%.(15) We observed that HCC-related transplants more than doubled following MELD implementation, and that the proportion of LT for HCC increased through 2017 when ~40% of all transplants were for HCC. Nonetheless, only 11.4% of all HCC patients (24.8% of patients with localized HCC) received a transplant within 5 years of diagnosis. Furthermore, the proportion of cases diagnosed with local stage HCC who receive a transplant has been declining since 2002 despite the increasing rate of LT for HCC (compare Figures 3A and 3B).

We used a counterfactual calculation to demonstrate that in the absence of LT, general population HCC mortality rates would have been higher than that observed. Despite this reduction in mortality, the impact of transplantation has not been larger because many cases are detected when they are no longer localized and thus too advanced for LT. Also, although a large fraction of LT is performed for HCC patients, these individuals still compete with others for available donor livers. The declining mortality rates among HCC cases who did not receive a transplant (Figure 4A) likely reflects the shift to earlier HCC diagnosis and improvements in treatment other than LT. Thus, though LT is a highly effective treatment for localized HCC at an individual level, the impact of transplantation on HCC mortality at the population level has been modest, as shown by our IBM analyses (Figure 4B).

A strength of our study was the linkage of cancer registries and the SRTR, which provided data on a large fraction of the US transplant population and near complete HCC ascertainment in participating states. We utilized IBM rates to examine mortality linked to incident HCCs by stage and transplantation status, and a validated algorithm to classify deaths as HCC-related.(16,17)

Our study also has some limitations. First, ~3% of HCCs appeared only in SRTR. Although they constituted a small minority of HCC cases, they comprised ~20% of transplant recipients with HCC. These cases may have been missed by cancer registries in the TCM Study due to migration of people across registry catchment areas. Nevertheless, these are genuine HCC cases as reflected by SRTR diagnoses. Second, we reclassified 2% of cancer registry cases to localized stage cancers. Because these patients received LT, we concluded that they were probably incorrectly staged in cancer registry data. LT is not routinely offered to individuals with localized HCC whose cancers progress while on the waiting list or whose cancers are beyond Milan criteria, unless they can be successfully downstaged to meet these criteria. Nonetheless, a prior review of pathology reports from 666 explanted livers revealed that the stage of ~30% of HCCs did not meet the Milan criteria at the time of transplantation, consistent with either progression of the cancer or underestimation of the stage prior to transplantation.(26) Third, we did not have data on other HCC treatments such as resection, ablation, or chemotherapy, or locoregional therapies for transplant candidates on the waitlist, which may have affected mortality. Fourth, only people with localized HCCs who fulfill the Milan criteria are eligible for LT, and patients in our study were not randomly assigned to receive LT. Because we applied mortality rates for non-transplanted cases to individuals who received an LT for calculating the counterfactual rates, we may have overestimated the benefit of LT. Finally, because the calendar years of coverage differed for included registries and organ sharing policies have changed over time, our results may not be representative of the experience of people who received liver transplants in the entire US population.

The increases in HCC incidence and mortality that we document point to the urgent need for substantially improved prevention, screening, and treatment options. Most LT for HCC is provided to relatively young patients, but the increase in HCC among older-age individuals has contributed strongly to the adverse overall trends.(27) Continued efforts to expand HCV treatment will be important, but barriers to uptake of antiviral medications remain, including the high cost.(28) HCC cases due to NAFLD are expected to increase by 137% between 2016 and 2030.(29) Screening for HCC in high-risk individuals, such as those with cirrhosis, using liver ultrasound (with or without serum alfa-fetoprotein testing) every 6 months is recommended.(4) However, current evidence supporting routine HCC screening with these techniques is inadequate, highlighting the need for better tumor markers and screening strategies.(30)

To the extent that HCC incidence continues to increase, and with a shift to localized stage diagnoses, demand for LT will rise. Models that select candidates with HCC whose tumors are beyond Milan criteria are being considered,(31) with the recognition that complete or partial response to down-staging treatment is an indicator of good tumor biology and acceptable post-transplant outcomes.(31) However, increasing demand for LT for HCC has outstripped the supply of available donor organs and has forced consideration of alternative allocation policies to foster greater opportunity for candidates with other indications for transplantation.(4,32) Indeed, changes in the MELD exception policy in 2015 deprioritized HCC patients and have likely led to a decline in the proportion of LTs for HCC.(24) Additional data will be required to evaluate the effect of recent changes in liver allocation policy on population-level HCC mortality rates.

In conclusion, LT has provided a survival benefit to people with localized HCC in the US. However, improvements in mortality for non-transplanted patients, limited availability of livers for transplantation, and diagnosis of many cases at advanced stages have kept the impact of transplantation on general population HCC mortality rates at a modest level. The rise in HCC incidence and mortality highlights the need for improved prevention, screening, and treatment for HCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance provided by individuals at the Health Resources and Services Administration, the SRTR, and the following cancer registries: the states of California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. We also thank Kelly Yu at the National Cancer Institute for study management, and analysts at Information Management Services for programming support (David Castenson, Matthew Chaloux, Michael Curry, Ruth Parsons).

Financial support:

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute.

PM, MSS, and EAE are employees of the National Cancer Institute and the Health Resources and Services Administration, which funded the study. The study design received scientific and administrative review by additional staff at the National Cancer Institute and the Health Resources and Services Administration. The manuscript was reviewed for scientific content and approved for release by the National Cancer Institute and the Health Resources and Services Administration. Other than the authors, no staff at either agency was involved in the conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation of the manuscript.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be interpreted to reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute, Health Resources and Services Administration, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), cancer registries, or their contractors

The SRTR is currently operated under contract number HHSH250201500009C (Health Resources and Services Administration) by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN. Previously the SRTR was managed under contracts HHSH250201000018C and HHSH234200537009C. The following cancer registries were supported by the SEER Program of the National Cancer Institute: California (contracts HHSN261201000036C, HHSN261201000035C, and HHSN261201000034C), Connecticut (HHSN261201800002), Iowa (HSN261201000032C and N01-PC-35143), New Jersey (HHSN261201300021I, N01-PC-2013-00021), and New York (HHSN261201800005I). The following cancer registries were supported by the National Program of Cancer Registries of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: California (agreement 1U58 DP000807-01), Colorado (U58 DP000848-04), Georgia (5U58DP003875-01), Illinois (5U58DP003883-03), New Jersey (NU58DP006279-02-00), New York (5NU58DP006309), and Texas (5U58DP000824-04). Additional support was provided by the states of California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, New Jersey, New York (including the Cancer Surveillance Improvement Initiative), and Texas.

Abbreviations:

- AAPC

Average annual percentage change

- CI

Confidence interval

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- IBM

Incidence-based mortality

- LT

Liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic liver disease

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- US

United States

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: Dr. Wong is a speaker for Eisai. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(6):394–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Njei B, Rotman Y, Ditah I, Lim JK. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology 2015;61(1):191–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, Ward JW, Jemal A, Sherman RL, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer 2016;122(9):1312–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68(2):723–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334(11):693–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, Natarajan Y, Chayanupatkul M, Richardson PA, et al. Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155(6):1828–37.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology 2003;124(1):91–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ioannou GN, Perkins JD, Carithers RL Jr. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of the MELD allocation system and predictors of survival. Gastroenterology 2008;134(5):1342–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg D, French B, Abt P, Feng S, Cameron AM. Increasing disparity in waitlist mortality rates with increased model for end-stage liver disease scores for candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma versus candidates without hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2012;18(4):434–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2019 Revised liver policy regarding HCC exception score. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/revised‐liver‐policy‐regarding‐hcc‐exception‐scores/.

- 11.Chu KC, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Hankey BF. A method for partitioning cancer mortality trends by factors associated with diagnosis: an application to female breast cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47(12):1451–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altekruse SF, Henley SJ, Cucinelli JE, McGlynn KA. Changing hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and liver cancer mortality rates in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(4):542–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF Jr., Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, et al. Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. Jama 2011;306(17):1891–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronin KA, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer 2014;120 Suppl 23:3755–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stage Summary 2018: Codes and Coding Instructions. In: Ruhl JL, Callaghan C, Hurlbut A, Ries LAG, Adamo P, Dickie L, et al. , editors. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howlader N, Ries LA, Mariotto AB, Reichman ME, Ruhl J, Cronin KA. Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102(20):1584–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2019 SEER Cause-specific Death Classification. https://seer.cancer.gov/causespecific/

- 18.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.6.0.0 - April 2018; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Statistics in medicine 2000;19(3):335–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrick JL, Kelly SP, Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Rosenberg PS. Future of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Incidence in the United States Forecast Through 2030. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(15):1787–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinheiro PS, Medina HN, Callahan KE, Jones PD, Brown CP, Altekruse SF, et al. The association between etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and race-ethnicity in Florida. Liver Int 2020;40(5):1201–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiels MS, O’Brien TR. Recent Decline in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Rates in the United States. Gastroenterology 2020;158(5):1503–5.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014;59(6):2188–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puigvehi M, Hashim D, Haber PK, Dinani A, Schiano TD, Asgharpour A, et al. Liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: Evolving trends over the last three decades. Am J Transplant 2020;20(1):220–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2010;16(9):1033–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiesner RH, Freeman RB, Mulligan DC. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular cancer: the impact of the MELD allocation policy. Gastroenterology 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S261–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiels MS, Engels EA, Yanik EL, McGlynn KA, Pfeiffer RM, O’Brien TR. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among older Americans attributable to hepatitis C and hepatitis B: 2001 through 2013. Cancer 2019;125(15):2621–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin M, Kramer J, White D, Cao Y, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, Madu S, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct-acting anti-viral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46(10):992–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018;67(1):123–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, O’Neil M, Freeman M, Relevo R, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2014;161(4):261–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta N, Yao FY. What Are the Optimal Liver Transplantation Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma? Clinical Liver Disease 2019;13(1):20–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heimbach JK, Hirose R, Stock PG, Schladt DP, Xiong H, Liu J, et al. Delayed hepatocellular carcinoma model for end-stage liver disease exception score improves disparity in access to liver transplant in the United States. Hepatology 2015;61(5):1643–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.