Abstract

Introduction:

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among the general population is 10.6%. Primary care doctors (PCDs) are often the first contact for patients with common psychiatric disorders, but the majority of them are ill equipped to handle the same leading to symptomatic treatment. Hence, an innovative digitally driven and modular-based 1-year primary care psychiatry program (PCPP) was designed and implemented exclusively for practicing PCDs of Uttarakhand.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to assess the impact of this digitally driven 1-year PCPP on the general practice of PCDs.

Materials and Methods:

Ten PCDs were trained in the curriculum module “Clinical Schedule for Primary Care Psychiatry” which is a validated concise guideline for screening, classification, diagnosis, treatment, follow–ups, and referrals. Furthermore, they underwent training in on-site basic module (10 days); three online modules (with nil or minimal disruption in their regular clinical work) – Telepsychiatric On-Consultation Training (Tele-OCT), Collaborative Video Consultations, and weekly virtual classroom; and one public health module. In addition, PCDs underwent 10 criteria-based formative assessment including self-reports of weekly patients' audit (Primary Care Psychiatry Quotient [PCPQ]) and quarterly Tele-OCT evaluation sessions (Translational Quotient [TQ]).

Results:

PCPQ was 11.09% (2182 psychiatric patients of total 19,670 general outpatients) which means 11.09% of PCDs' total general consultations had psychiatric disorders, which would have been otherwise missed. Average scores obtained in first and second Tele-OCT evaluations (similar to clinical examination but in their real-time consultation) were 70.33% and 76.33%, respectively, suggestive of adequate TQ at 6 and 9 months of the course.

Conclusions:

One-year PCPP is shown to be effective in acquiring psychiatry knowledge, skills, and retention of skills (TQ) and also translated in providing psychiatric care in general practice with a positive impact on the delivery of primary care psychiatry.

Keywords: General practice, India, primary care, psychiatry, telepsychiatry

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Mental Health Survey, 2016, the current prevalence of psychiatric disorders in India is 10.6%.[1] Common mental disorders (CMDs) form the significant bulk with a prevalence of around 10%, whereas severe mental disorders have a prevalence of 0.8%.[1] The treatment gap for most of the psychiatric disorders is around 80%.[1] The total number of psychiatrists registered as members of the Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS) is 6475 as on June 30, 2020; however, few of them may not be working in India (as per the personal communication with Professor TSS Rao, General Secretary of IPS). However, there are reasons to believe that there are about 9000 psychiatrists are working in India.[2] Going by this data, we have 0.75 psychiatrists per 100,000 populations, whereas the estimated desirable is more than 3 per lakh. Taking these data into consideration, India requires 36,000 psychiatrists. Hence, we have a deficit of around 27,000 psychiatrists.[2]

The second area to be taken into consideration is the distribution of the Indian population. Around 70% of the Indian population reside in rural areas,[3] whereas the distribution of doctors/mental health professionals follows an opposite trend, with a concentration of specialists in urban areas.[4] This hampers the delivery of services to the majority of the Indian population. Primary care doctors (PCDs) are most often the first contact for these patients. Several studies have been conducted to study the prevalence of CMDs in patient population consulting PCDs and have shown that 17%–46% of this population need psychiatric care.[5] However, majority of PCDs are ill equipped to handle the psychiatric disorders and provide symptomatic treatment which further lead to chronicity of illnesses in the population.[6]

Only 29% of the mental health needs of the Indian population are being catered by available human resources.[4,7] Huge discrepancies between urban and rural distribution of available psychiatrists and lack of referral system makes it all the more difficult to cater needs of people living with socioeconomic deprivation who have the highest need for mental health care. All the above-mentioned reasons contribute to the primary reason of deficiency of human resources for psychiatric care to compound the mental health gap.[4] Taking into consideration this insuperable treatment gap with an amalgam of factors responsible for the same, overcoming this problem with the view of bolstering and expanding human resources appears to be intractable considering the logistic difficulties.

Integrating psychiatric care into primary health care appears to be a viable option to manage the above-mentioned roadblocks. Dysfunctional work patterns of PCDs are the reason for “functional treatment gap” at primary care to provide psychiatric treatment but provide symptomatic treatment to them.[6] Traditional classroom training (CRT) programs involving didactic lectures, video demonstrations, and PowerPoint presentations in group format are often conducted for these PCDs serving in government sector. Translation Quotient (TQ)[6] of CRT programs is questionable as they often fail in translating clinical skills required for early diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders. Reasons for poor TQ include delivery of curriculum of tertiary care psychiatry by psychiatrists, lack of continuous support and follow-up, top–down authoritarian approach, knowledge enhancing rather than skill-enhancing approach, and absence of adult learning principles. Alternatively, specialist psychiatrists in urban areas can be connected to PCDs with the availability of high-speed Internet and smartphones even in rural areas to ensure specialist consultations to patients in rural areas. This may be considered as a short-term solution to bridge the gap of psychiatric care. Task shifting, i.e., empowering PCDs to take care of psychiatric disorders in their general practice itself, appears to be the only long-term pragmatic, tangible, and viable option to cater to this crisis.[6]

Uttarakhand is the 27th state of India carved out of Uttar Pradesh in November 2000. It is the 20th most populous state of the country, with a population of 1.01 crores. It has 13 districts; seven lie in the Garhwal region, and the rest six in the Kumaon region. It has 15,669 villages. The shortfall of trained specialists makes it difficult to deliver even primary mental health care to this populous state.[8]

To address this public health issue, the Tele Medicine Centre, Department of Psychiatry at National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, India, a pioneering institute for neuropsychiatric care in India, designed an innovative approach and path-breaking 1-year, part-time, modular-based, digitally driven primary care psychiatry program (PCPP) dedicated for Uttarakhand PCDs that seeks to overcome above-mentioned criticisms. It is a 1-year program to train PCDs of Uttarakhand, which was recognized as “diploma in primary care psychiatry” (DPCP) by statutory bodies of NIMHANS Bengaluru, India.

PCDs undergo training from their hospital (earn a clinical diploma from your clinic rather than coming to a tertiary care academic hospital). A telepsychiatrist from NIMHANS, Bengaluru, trained all these PCDs in live, real-time, video streaming of their own consultations from their outpatient clinic. The first batch of DPCP trained 10 PCDs from Uttarakhand to identify, screen, and treat/refer cases of psychiatric disorders, using telemedicine technology, from March 2018 to March 2019.

Aim

The aim of the study was to assess the impact of this 1-year, digitally driven, part-time, modular PCPP on the general practice of the first batch of PCDs of Uttarakhand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is an interventional naturalistic study conducted at Tele Medicine Centre, Department of Psychiatry, NIMHANS, Bengaluru. Ethical Committee of NIMHANS, Bengaluru, approved this study.

Participant primary care doctors

Ten PCDs with qualification MBBS degree working in district hospitals (n = 6), community (n = 2), and primary health centers (n = 2) in various districts of Uttarakhand were deputed by the Government of Uttarakhand for DPCP course. Of the deputed 10 PCDs, two had some previous exposure to training in psychiatry (one worked in the department of psychiatry and other was, along with his general primary care, also working in de-addiction and opioid-substitution program).

Diploma in primary care psychiatry

Course curriculum, delivery modules, and assessments

DPCP is a 1-year, six module-based program incorporated ten criteria-based formative assessment and an exit examination. The training modules are curriculum module (Clinical Schedule for Primary care psychiatry) briefed below, basic (onsite, 10 days, residential), Telepsychiatric On-Consultation Training (Tele-OCT)/Virtual Classroom (VCR)/videoconference-based continuing skill development (V-CSD), collaborative video consultation (CVC), and public health modules.[9] Apart from the basic module, the rest four modules are digital modules and public health are home assignment module. Each of them has different objectives. PCPP involves principles of adult learning and top–down approach. It involves teaching PCDs screening methods, early detection and providing first-line standard treatment of psychiatric disorders, and referring relevant cases to higher center, with a minimum interference in their busy clinical workflow. To make sessions more structured and effective, a curriculum module called “Clinical schedules for primary care psychiatry” (CSP)[10] designed by the primary care psychiatry team of NIMHANS was used for the training of PCDs. A detailed description of PCPP/DPCP is available elsewhere.[6]

Clinical schedule for primary care psychiatry (version 2.1)[10]

CSP is an all-in-one integrated, adopted, validated tool for PCDs to provide the first-line, safe, and effective pharmacotherapy for highly prevalent six psychiatric disorders at primary care which include tobacco addiction, alcohol (harmful and addiction), psychotic, depressive, anxiety (panic and generalized anxiety disorders), and somatization disorders (TAPDAS). It consists of the screener, classification of psychiatric disorders adapted for use in primary care settings, diagnostic criteria, referral points, and management guidelines for these six highly prevalent psychiatric disorders. The CSP screener consists of a questionnaire containing 21 culturally appropriate questions to screen patients for TAPDAS. CSP uses a cluster-based transdiagnostic classification of psychiatric disorders adopted for the use of PCDs. Clusters are (1) CMDs cluster subdivided as predominantly depressive, anxiety, somatization, or mixed symptoms; (2) psychotic disorder cluster subdivided as acute (cover acute psychosis and mania), chronic (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders), or episodic (focus on bipolar disorder); and (3) alcohol disorders simplified as harmful (frequent and infrequent type) and addiction with simplified diagnostic criteria for primary care use. CSP version 2.1 designed by primary care psychiatry team at NIMHANS Bengaluru is available on request for readers. CSP version 2.2 is available elsewhere[11] and downloadable at http://nimhansdigitalacademy.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CSP-2.2-Oct-2018.pdf. Management guidelines in CSP include pharmacotherapy, brief counseling, and follow-up guideline along with strategies for referral guidelines. CSP screener has inbuilt pragmatism of real-world scenarios. It is adopted and validated with higher sensitivity and specificity at primary care.[10]

Basic on-site module[12]

A basic module which consisted of 10-day on-site residential training in NIMHANS, Bengaluru, was conducted for 10 PCDs of Uttarakhand. This was the first module of this 1-year course and was scheduled from 15 to 24 March 2018. During this training, PCDs were oriented to CSP; attended NIMHANS outpatient department where demonstrations of clinical examination in psychiatry were done and underwent in-person OCT for first and follow-up consultations; trained to screen, diagnose, and manage/refer first consultations psychiatry patients (TAPDAS) using CSP; and oriented to Tele-OCT. Didactic classroom teaching sessions on TAPDAS and specialty topics such as Child, Perinatal, Medicolegal and Disaster Psychiatry, Emergency Psychiatry, and Sexual and Sleep Disorders were also conducted. PCDs also were taken for a field visit to the District Mental Health Program of Ramanagara district, Karnataka. A live demonstration of electroconvulsive therapy was conducted. PCDs visited emergency psychiatry ward of NIMHANS. On-site module was concluded after obtaining feedback from all ten PCDs regarding the training. Further details of the on-site module have been mentioned elsewhere.[12]

Telepsychiatric on-consultation training[6]

OCT is on-job/hand-holding training conducted in live, real-time clinical scenarios where PCDs are providing consultations to their general patients with minimal disruption to their clinical work. The goal of OCT is to maximize the quality of the general practice of PCDs with the provision of standard psychiatric care to patients with psychiatric disorders. It incorporates the principles of “real patients, real consultations, but with new clinical practice acumen,” andragogy, bottom–up approach wherein each and every clinical skill is taken care separately from entry-to-exit of patients, and the principle of two-way learning with equal partnership as there are 50% chances of getting a psychiatric patient during consultations, and hence, telepsychiatrist trains PCDs on psychiatric patients and PCDs give inputs to telepsychiatrist on nonpsychiatric patients enabling a two-way learning process.[6] It uses Hub (telepsychiatrist at NIMHANS)-and-Spoke (Uttarakhand doctors at their workplace hospitals) model and training is structured based on CSP. Two to three Tele-OCT sessions were conducted for each doctor. It was a one-to-one session conducted for about 2–3 h in 10–15 general patients in each session. In the first session, telepsychiatrists are demonstrated about interview skill using screener and subsequent treatment algorithm of CSP (from the screener, checking diagnostic criteria, finding diagnosis from taxonomy, plan of first-line treatment, choosing appropriate medication and its dosage, and writing a prescription to each patient using the prescription template) for consecutive general patients and PCDs were asked to simply see themselves, and in next session, PCDs were encouraged to try similar clinical interviewing and at last asked to do-it-yourself in their clinical flow (See-, Try-, and Do-It-Yourself teaching methodology). The Tele-OCT has dual outcomes: training of clinical direct skill transfer and consultation from collaborative care. A total of 22 Tele-OCT training and 24 Tele-OCT evaluation sessions were conducted for these ten PCDs. Each session lasted for 2–3 h and 10–15 patients were seen in each session. Further details of Tele-OCT are available elsewhere.[6,11]

Virtual classroom/videoconference-based continuing skill development module

It is based on the principle of peer learning wherein interactive sessions in the form of seminars, case conferences, and expert lectures were conducted every Tuesdays between 3 and 4 PM. They are of two types:

Conducted by PCDs: They are based on TAPDAS disorders and content was collaboratively prepared with a telepsychiatrist working with them

Conducted by experts: Conducted on psychiatric subspecialty topics.

In this batch of PCDs, Under VCR/V-CSD module, PCDs conducted 11 seminars (on TAPDAS) and 10 case conferences (cases are from their own clinic, verified and collaboratively prepared PowerPoint with help of trainer telepsychiatrist) on different topics. Experts conducted 18 1-h interactive lectures for PCDs on specialty topics (Neuropsychiatry [n = 3], Emergency Psychiatry [n = 1], Child and Adolescent Psychiatry [n = 4], Geriatric Psychiatry [n = 2], Women mental Health [n = 1], and Sleep Medicine [n = 2]) with relevance to primary care practice. Attendance of each PCD for number of this module ranged from 72% to 100%.

Collaborative video consultations module

This module based on the practice-based learning. Live and real-time video-based assistance was provided by a telepsychiatrist from 9 am to 4:30 pm on all working days for discussion of selected cases by PCDs. This module began for each PCD only after first Tele-OCT session. PCDs chose cases for discussion with trainer telepsychiatrist and both of them collaboratively decided the best management plan for selected patients. Some of these patients were followed up for 6 months. A total of 315 CVCs with an average of 32 CVC (highest 69 CVC) per PCD were conducted in 1 year. Each PCD also completed follow-up of five psychiatric patients for 6 months (a criteria of formative assessment).

Public health module

It was home assignment module. Under this module, it was mandatory for PCDs to design a public education material and deliver public health talk/initiative. Under public health module, 25 public initiatives were conducted and 14 public education materials were designed. Trainer telepsychiatrist checked for quality content and provided necessary feedback to them.

Assessment: Formative and summative

This DPCP program had 10 formative assessments for each PCD throughout the year. The ten criteria were one case conference (collaborative and verified), one seminar (collaborative and verified), 25 CVC consults, 6-month follow-up CVC for at least 5 patients, weekly audit of total and psychiatric disorders, wherein PCDs entered details of general and psychiatric patients in a Google form, weekly prescription audit of psychiatric medications, wherein PCDs sent their prescriptions of psychotropics for audit, substantial attendance for VCR/V-CSD module (>50%), periodic Tele-OCT evaluation sessions, conducting at least one public initiative, and designing at least one public education material. This DPCP course also had a summative assessment (exit exam) at the end of the course which is beyond the scope of this article.

Outcome parameters

Since it was an innovative training program, the authors have defined two pragmatic outcome parameters to evaluate the effectiveness of 1-year PCPP; primary care psychiatry quotient (PCPQ), and TQ.

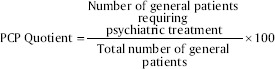

Primary care psychiatry quotient

PCPQ is defined as the proportion of psychiatric caseness among total general patients of PCDs. It may be equated with a prevalence of psychiatric disorders at primary care.

As described above, 17%–46% of the patient population consulting PCDs have psychiatric disorders.[5] Considering this, the authors feel that PCPQ of around 30% may be considered adequate for a primary care psychiatry training program.

PCPQ was calculated from weekly self-report of patients audits of all PCDs. This was one of the criteria of formative assessment.

Translational quotient

TQ assesses the degree of integration of psychiatry clinical skills among PCDs in their real primary care clinical scenario. TQ of a training program can be defined as ability of a training program to translate learnt/taught knowledge into clinical skills required for use during the routine busy clinical practice. This quotient is the most crucial requirement for early diagnosis and first-line treatment at primary care level by PCDs.[6] In this study, TQ was assessed two Tele-OCT evaluative sessions were conducted by a tele-psychiatrist for each PCD at 6 and 9 months after the course started in a live video streaming of their real-time general outpatient consultations. These evaluations were conducted by a telepsychiatrist working in primary care psychiatry but not trained that particular PCD. PCDs were evaluated based on six criteria: elicitation of psychiatric symptoms using CSP screener, clinical reasoning of caseness for psychiatric diagnosis, an appropriate decision regarding choosing psychiatric medications, coverage of components of brief counseling to patients, time management for psychiatric evaluation at primary care level, and overall clinical psychiatric skills. Each criterion was scored between 1 and 5 with a minimum total score of 6 and maximum score of 30.

RESULTS

Primary care psychiatry quotient

According to the weekly audit of 34 weeks (response rate for this weekly audit was 65.4% [34 weeks of 52 weeks]), 2182 psychiatric patients of total 19,670 general consultations were identified in a year that otherwise might have got missed. The estimation of 1-year PCPQ in this study was 11.09%. Table 1 gives details of the number of patients with various psychiatric disorders, seen by PCDs during this period.

Table 1.

Self-report of primary care doctors on their pattern of consultations in general practice (total=19,670)

| Disorder | Number of consultations (%) |

|---|---|

| Nil psychiatry | 17,480 (88.86) out of 19,670 total general consultations |

| Total consultations with one or more psychiatric disorder/s | 2182 (11.09) of 19,670 total general consultations |

| Differential psychiatric disorders (n=2182)*, n (%) | |

| Tobacco use disorder | 451 (20.66) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 202 (9.25) |

| Psychosis | 108 (4.94) |

| Depressive disorder | 413 (18.92) |

| Anxiety disorders | 400 (18.33) |

| Somatization disorder | 412 (18.88) |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 501 (22.96) |

*Please note that one patient had one or more psychiatric disorders

Translational quotient

Average scores obtained in the first and second Tele-OCT evaluation were 70.33% (53.34%–86.67%) and 76.33% (53.34%–86.67%), respectively. Table 2 gives the number of patients and their psychiatric diagnoses made during Tele-OCT evaluation sessions.

Table 2.

Number of consultations during evaluation telepsychiatric on-consultation training sessions (total=109)

| Disorder | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Nil psychiatry | 63 (57.8) of 109 total general consultations |

| Total consultations with one or more psychiatric disorders | 46 (42.2) of 109 total general consultations |

| Differential psychiatric disorders (n=46)*, n (%) | |

| Tobacco use disorder | 13 (28.26) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 8 (17.39) |

| Psychotic disorder | 2 (4.34) |

| Depressive disorder | 16 (34.78) |

| Anxiety disorders | 5 (10.86) |

| Somatization disorder | 7 (15.21) |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 3 (6.52) |

*Please note that one patient had one or more psychiatric disorders

DISCUSSION

It is the first study to evaluate the impact of innovative digitally driven PCPP with innovative as well as pragmatic outcome clinical parameters such as PCPQ and TQ.

Evaluation measures of the impact of the training program are the essence of these training programs. The best measures of the outcome are changes in clinical practice like rates of prescriptions, referrals, illness detection, and hospitalization.[13] PCPQ is one such outcome measuring psychiatric illness detection by PCDs in their general patient population. PCPQ in this study was 11.09% indicated that around 11% of patients visiting general care at their PHCs provided first-line psychiatric care by these trainee PCDs. Without psychiatric training, these patients usually receive symptomatic treatment, wherein these disorders become chronic and cause significant disability in functioning. Hence, this 1-year PCPP addressing this gap is a good beginning, with considering the prevalence of psychiatric disorders at primary care being 17%–46%.[5]

Heterogeneity in the types of interventions for training PCDs in psychiatry makes it difficult to derive measures for assessing effectiveness of these programs. A 50 years review of about 400 articles of PCDs training reported that the three important variables are important for the effectiveness of training program such as the duration of the intervention, the degree of active participation of the learners, and the degree of integration of new learning into the learners' clinical context.[13,14]

Apart from theoretical knowledge, attitude toward psychiatric patients and clinical skills are paramount for effective psychiatric practice which is possible only in long-term programs rather than short conferences/lectures of hours to days.[13,15] Furthermore, providing continuous support to PCDs is more likely to improve the quality of care rather than just optimizing the number of psychiatrists.[13,16] This was 1-year program consisted of initial two weeks on-site classroom and consultation based trainings, followed by continuous support with remaining clinical as well as public health modules in the remaining period along with incorporation of adult learning principles, interactive sessions may be responsible for effectiveness of PCPP.

The level of active participation and involvement of PCDs is a pointer of effectiveness of a training program. Opportunities to practice the acquired knowledge and skills in real-life scenarios,[13,17] models of collaborative care,[13,18] and interactive sessions may influence the clinical practice of PCDs. Under tele-OCT and CVC modules, PCDs were given opportunities to execute their knowledge and skills along with collaborative care by a telepsychiatrist (via video consultations), which was reflected by their involvement in modules, as an average of 32 CVCs were conducted (wherein required CVC for formative assessment were 25) which also indicated intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, public health module provided opportunities to PCDs to share their knowledge with general public to increase awareness, wherein 25 public initiatives were conducted and 14 public education materials were designed. Furthermore, the programs wherein the trainees are in proximity to their site of clinical practice with supervising telepsychiatrist in real clinical role have been found to be the most effective models.[13,18,19] This program fulfill both criteria of proximity of PCDs at their own live outpatient consultation of general pratice and simultaneously virtual clinical support from a telepsychiatrist for same patients.

A degree of integration of psychiatry clinical skills was measured using TQ. TQ of around 70.33% and 76.33% in the first and second evaluative Tele-OCT session, respectively, at 6 and 9 months after commencement of training indicates adequate skill transfer and retention in terms of screening questions, interpretation of psychiatric signs and symptoms, diagnosing common psychiatric disorders and providing first-line and follow-up treatments and referral of appropriate patients, and collaborative care to general patients.[6]

Limitations and future directions

This study assessed the collective impact of all six modules, not individual module, of DPCP in general practice of PCDs. The baseline assessment of PCPQ and TQ was not done. Impact of individual module in sequential way needs to be assessed, i.e., at the end of each Tele-OCT session and every fifth CVCs.

CONCLUSIONS

One-year PCPP is shown to be effective in acquiring psychiatry knowledge, skills, and retention of skills and also translated in providing psychiatric care in general practice with a positive impact on delivery of primary psychiatric care services and also contributed to increasing awareness about mental health among people.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by the National Health Mission, Government of Uttarakhand.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the assistance of staffs from Tele Medicine Centre, NIMHANS, Bengaluru. The authors acknowledge the feedback from faculties of the Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, during the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murthy RS. National mental health survey of India 2015-2016. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:21–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_102_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg K, Kumar CN, Chandra PS. Number of psychiatrists in India: Baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:104–5. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudhira H, Gururaja K. Population crunch in India: Is it urban or still rural? Cur Sci. 2012;103:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R. Telepsychiatry: Promise, potential, and challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:3–11. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nambi SK, Prasad J, Singh D, Abraham V, Kuruvilla A, Jacob KS. Explanatory models and common mental disorders among patients with unexplained somatic symptoms attending a primary care facility in Tamil Nadu. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB, Thirthalli J. Designing and implementing an innovative digitally driven primary care psychiatry program in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:236–44. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_214_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehradun U. India: WHO and Ministry of Health; WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health System in Uttarkhand, India. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of Uttarakhand. UTTARAKHANDGovernment Portal. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 March 26]. Available from: https://uk.gov.in/

- 9.Pahuja E, Santosh KT, Harshitha N, Fareeduzaffer, Manjunatha N, Gupta R, et al. Diploma in primary care psychiatry: An innovative digitally driven course for primary care doctors to integrate psychiatry in their general practice. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102129. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni K, Adarsha AM, Parthasarathy R, Philip M, Shashidhara HN, Vinay B, et al. Concurrent Validity and Interrater Reliability of the “Clinical Schedules for Primary Care Psychiatry”. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2019;10:483–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB, Vinay B, Shashidhara HN, Parthasarathy P, et al. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, NIMHANS Publication No. 157, 2019; [Last accessed on 2020 Jul 27]. Karnataka Telemedicine Mentoring and Monitoring Program: An Implementation Manual of Primary Care Psychiatry. ISBN: 978-81-86506-00-4. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334048173_Karnataka_Telemedicine_Mentoring_and_Monitoring_KTM_Program_An_implementation_Manual_of_Primary_Care_Psychiatry . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni K, Gowda GS, Malathesh BC, Kumar S, Manjunatha BR, Shashidhara HN, et al. Conference summary of “Ten days, on-site training of basic module of 'primary care psychiatry program' for primary care doctors of Uttarakhand”. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:29–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodges B, Inch C, Silver I. Improving the psychiatric knowledge, skills, and attitudes of primary care physicians, 1950-2000: A review. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1579–86. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg K, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Chand PK, Math SB. Case vignette-based evaluation of psychiatric blended training program of primary care doctors. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:204–7. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_250_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher RM, 3rd, Chapman RJ. The medication seminar and primary care education. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1981;3:16–23. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(81)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley D, Korsen N, Bird D, Agger M. Management of patients with depression by rural primary care practitioners. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:139–45. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soumerai SB. Principles and uses of academic detailing to improve the management of psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28:81–96. doi: 10.2190/BTCA-Q06P-MGCQ-R0L5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rittelmeyer LF, Jr, Flynn WE. Psychiatric consultation in an HMO: A model for education in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:1089–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]