Introduction

LEOPARD syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant inherited or sporadic disease associated with high penetrance and phenotypic variablity.1 It is caused by mutations in the protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor 11 (PTPN11), B-RAF, and RAF1 genes.2 The acronym LEOPARD refers to the main manifestations of the syndrome, namely, Lentigines, Electrocardiogram conduction abnormalities, Ocular hypertelorism, Pulmonary stenosis, Abnormal genitalia, Retarded growth, and sensorineural Deafness.

Herein, we report a case of LS, in which we identified a novel mutation in the PTPN11 gene.

Case report

A 43-year-old Jewish man born to healthy, non-consanguineous parents presented at the dermatology ward for the evaluation of multiple pigmented lesions, which, according to the patient, initially appeared at the age of 3 years and gradually increased in number. The patient was otherwise healthy.

The patient was born at term after a pregnancy with no significant complications or neonatal problems. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous flat brown-to-black-colored macules (lentigines) on the face, neck, torso, back, and limbs (Figs 1 and 2). Physical examination revealed a facial dysmorphism, including ocular hypertelorism, broad nasal root, low set ears, and pectus excavatum. A skin biopsy specimen showed features suggestive of lentigo simplex (Fig 3).

Fig 1.

Multiple lentigines on the face and neck along with hypertelorism, broad nasal root, and low set ears.

Fig 2.

Multiple lentigines on the back along with winged scapula.

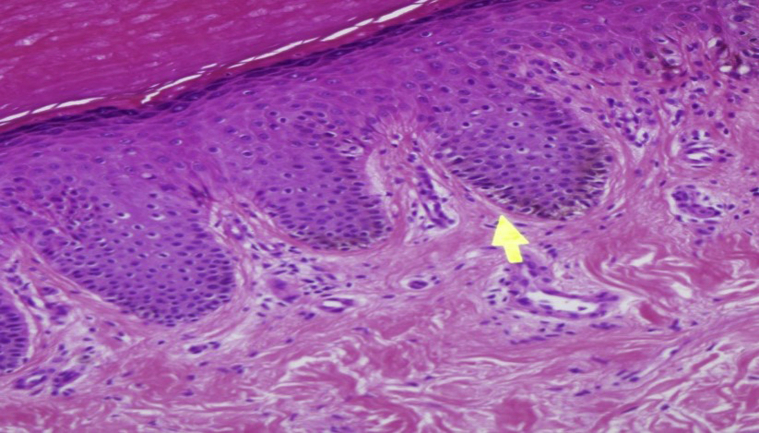

Fig 3.

Histopathology showed mild epidermal acanthosis, increased numbers of melanocytes without atypia in the basal layer, and variable basal hyperpigmentation. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain.)

There was no previous family history of lentigines. Since LS was clinically suspected, the following further investigations were conducted: Audiometry revealed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (>2000 Hz). Cardiac evaluation revealed a conduction abnormality (AV Block, Mobitz 1) in Holter, electrocardiogram values were within the normal limits, and Echo was normal with no evidence of pulmonary stenosis. Sanger sequencing of the coding regions of the PTPN11 gene revealed a novel heterozygous mutation at C.380C>T in exon 4 (Thr127Ile). The patient's parents were not found to carry the same genomic change.

Discussion

LS is a rare disease. Approximately 200 patients have been reported worldwide, but the real incidence of LS is not known.1 Most cases are caused by a germline PTPN11 missense mutation. However, mutations in the RAF1 and B-RAF genes have also been reported.2

According to Sarkozy et al, in approximately 85% of the cases, a heterozygous missense mutation is detected in exons 7, 12, or 13 of the PTPN11 gene.3 In our case report, we present a novel mutation located at exon 4 in the PTPN11 gene.

The PTPN11 gene encodes for the SRC homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing PTPase protein, characterized by 2 tandemly arranged SH2 (N-SH2 and C-SH2) domains and one protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) domain. SRC homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing PTPase functions as a cytoplasmic signaling transducer downstream of multiple receptors for growth factors, cytokines, and hormones, with a particular role through the RAS-mitogen activated protein kinase pathway.4,5

These genes are considered oncogenes. Once mutated, oncogenes have the potential to cause normal cells to become cancerous. Therefore, patients with LS are possibly at an increased risk of malignancy.6

The differential diagnosis of patients with multiple lentignies includes the following in addition to LS: Carney Complex, Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Ruvalcaba-Myhre-Smith syndrome, Bannayan-Zonnana syndrome, Cowden disease, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and benign lentiginoses.7

Voron et al8 proposed that diagnostic criteria of LS should require diffuse lentiginosis and 2 other syndrome traits. If diffuse lentigines are absent, the presence of a first-degree affected relative and 3 other distinct features are necessary for diagnosis.

In our case, the current clinical diagnostic criteria were fulfilled by lentigines and 4 minor criteria (cephalofacial dysmorphism, cardiac findings, deafness, and pectus excavatum). In addition, genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis (novel mutation in PTPN11).

In this report, we would like to emphasize the importance of detailed clinical evaluation and appropriate assessment in patients with multiple lentigines.

Genetic testing of patients with suspected or established diagnosis of LS is highly advisable, since it may assist in making the diagnosis or confirm it. However, more importantly, it may provide familial genetic counseling.

There is no published accepted follow-up protocol for patients with LS. However, we suggest the following clinical follow-up protocol based on the various possible types of systemic involvement: hearing test, cardiologic evaluation (echocardiography and electrocardiogram), growth parameter monitoring in children, neurological, and urogenital evaluations. Full-body photography and dermoscopy follow-up are also important due to the possibly large number of nevi.

The frequency by which these assessments should be conducted remains unclear, but we would advise evaluation at least once every 2 years, and surely earlier, if clinical symptoms and/or signs appear.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Sarkozy A., Digilio M.C., Dallapiccola B. Leopard syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelb B.D., Tartaglia M. Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines. In: Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle (WA): 1993. p. 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkozy A., Conti E., Digilio M.C. Clinical and molecular analysis of 30 patients with multiple lentigines LEOPARD syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41(5):e68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neel B.G., Gu H., Pao L. The 'Shp'ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(6):284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartaglia M., Niemeyer C.M., Shannon K.M., Loh M.L. SHP-2 and myeloid malignancies. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11(1):44–50. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kratz C.P., Rapisuwon S., Reed H., Hasle H., Rosenberg P.S. Cancer in Noonan, Costello, cardiofaciocutaneous and LEOPARD syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(2):83–89. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodish M.B., Stratakis C.A. The differential diagnosis of familial lentiginosis syndromes. Fam Canc. 2011;10(3):481–490. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9446-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voron D.A., Hatfield H.H., Kalkhoff R.K. Multiple lentigines syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1976;60(3):447–456. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]