Abstract

Objective

To determine the predisposition to use roll-your-own (RYO) cigarettes and the beliefs about RYO cigarettes of all the students of 3°–4° of ESO during the years 2016–17 and 2018–19. A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Bisaura High School from Sant Quirze de Besora. Primary Health Care in the Catalan Health Institute, Catalunya, Spain.

Participants

111 3rd and 4th of ESO (14–16 years).

Main measurements

Dependent variables used were future intentions of smoking and beliefs regarding RYO cigarettes. Independent variables were sex, course and ever smoked. The prevalence of the different dependent variables was described and compared according to the different independent variables with Pearson's Khi-square test.

Results

26.6% of the adolescents intended to smoke in the future of which 17.4% intended to smoke RYO cigarettes and 13.8% manufactured cigarettes (MC). Around 30% of adolescents express at least one wrong belief regarding RYO cigarettes. For example, the 26.7% believed that smoking RYO cigarettes generated less addiction than MC and the 32.1% that was less harmful. Those who had smoked at some time in their life had a greater intention to smoke in the future (54.5%), to smoke MC (27.3%) and RYO cigarettes (40.9%) than those who had never smoked (7.7%, 4.6% and 1.5% respectively) (p < 0.005). Some misconceptions differed depending on whether adolescents had ever smoked in life, sex and course. The boys believed that smoking RYO cigarettes was more natural than smoking MC (p < 0.005).

Conclusions

Educational activities to improve the information that young people have regarding RYO cigarettes are needed.

Keywords: Roll-your-own cigarettes, Manufactured cigarettes, Beliefs, Adolescents, Smoking intention

Abstract

Objetivo

Conocer la predisposición a usar tabaco de liar (TL) y las creencias sobre TL de todos los alumnos de 3°-4° de ESO durante los cursos 2016-17 y 2018-19. Estudio tansversal.

Emplazamiento

Institut Bisaura. Sant Quirze de Besora. Atención Primaria de Salud. Instituto Catalan de la Salud, Catalunya, España.

Participantes

111 adolescentes de 3° y 4° de ESO (14-16 años).

Mediciones principales

Variables dependientes: intenciones futuras de fumar y creencias con respecto al TL. Variables independientes: sexo, curso y haber fumado o no en la vida. Se describió la prevalencia de las variables dependientes y se comparó según las distintas variables independientes con la prueba de Chi cuadrado de Pearson.

Resultados

El 26,6% de los adolescentes manifestaron intención de fumar en el futuro, y de ellos, el 17,4% tenían intención de fumar TL y 13.8% tabaco manufacturado (TM). Alrededor del 30% de los adolescentes expresaron al menos una creencia errónea con respecto al TL. Concretamente, el 26,7% creía que fumar TL generaba menor adicción que fumar TM y el 32,1% creía que era menos perjudicial. Los que habían fumado alguna vez en la vida tenían mayor intención de fumar en el futuro (54,5%), de fumar TM (27,3%) y TL (40,9%) que los que no habían fumado nunca (7,7%, 4,6% y 1,5%, respectivamente) (p < 0,005). Algunas creencias erróneas difirieron según si los adolescentes habían fumado alguna vez en la vida, el sexo y el curso. Los chicos creían que fumar TL era más natural que fumar TM (p < 0,005).

Conclusiones

Son necesarias actividades educativas para mejorar la información que tienen los jóvenes con respecto al TL.

Palabras clave: Tabaco de liar, Tabaco manufacturado, Creencias, Adolescentes, Intención de fumar

Introduction

Tobacco consumption remains a major public health problem, being one of the leading causes of illness and death in developed countries.1, 2 Although in 2004 tobacco consumption started to decline, in 2016 was the second most used drug in Spain after alcohol and 8.8% of secondary school students between 14 to 18 years consumed daily.2 Among smokers, especially among young people, the proportion of people who use roll-your-own (RYO) cigarettes has grown.3, 4 In general, students start smoking manufactured cigarettes (MC) at an early age, concretely at 14.1 years and as the years go by they start smoking RYO.5 In Catalonia, the percentage of smokers who use RYO daily increased from 4.6% among men and 1.7% among women in 2006 to 29.6% and 22.6% respectively, in 2015.6 Also in Barcelona, the prevalence of smokers who use RYO increased from 0.4% in 2004–05 to 3.7% in 2011–12.7 With these consumer trends, it is estimated that by 2020 there will be a decrease in MC smokers, whereas RYO consumers will increase.3

On the one hand, RYO consumption growth can be explained by several economic reasons, as well as tobacco industry business strategies to attract new customers. For that matter, RYO has a lower price than MC,8 which makes some smokers choose this option instead of making an attempt to quit smoking.9 Moreover, some RYO smokers state it tastes better.10, 11 On the other hand, RYO consumption increase could also be explained by false beliefs about it. Many young people think that smoking RYO is less addictive, so they believe they have more personal control over its consumption.8 In fact, they also believethat is less harmful and has less additives than MC.7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 However, there are comparative studies that show that smoking RYO is more damaging to health than smoking MC, with RYO having higher concentrations of nicotine, tar and carbon monoxide18, 19, 20, 21 and even more tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs).13

Given the few existing studies on adolescent RYO smoking in Spain, the aim of the study is to know the predisposition to use RYO and RYO beliefs on 3°–4° ESO students during the 2016–17 and 2018–19 school years.

Methods

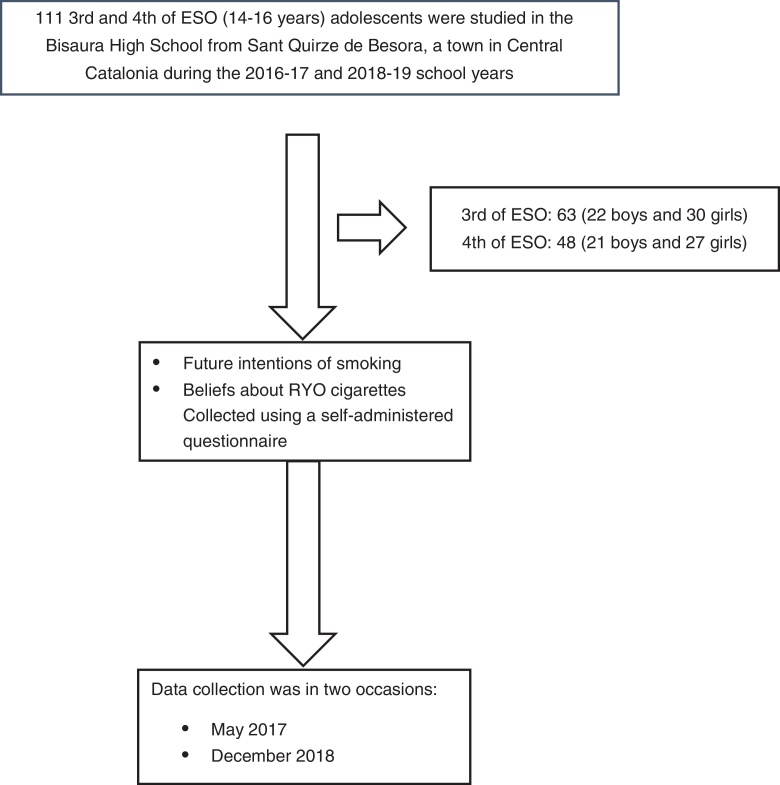

Study design

A Cross-sectional study during the 2016–17 and 2018–19 school years was carried out. All students in 3rd and 4th year of Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO, equivalent to 9–10th grades) from the Bisaura High School in Sant Quirze de Besora, a town in Central Catalonia (14–16 years) participated in the study, with a total of 111 participants. Smoking habits in the last 30 days (consumption frequency and daily smoked cigarettes), future intentions of smoking and beliefs about RYO cigarettes were collected using a self-administered questionnaire with the same questions that were used in the didactic unit: “Fumar? Jo No m’hi Embolico!8 Data collection was in two occasions: May 2017 and December 2018. The questionnaire was answered during school hours with the presence of the person responsible for the study, who provided instructions to complete the questionnaire and answered questions. The questionnaire was administered during school hours. Although participation in the study was voluntary, all students answered the questionnaire (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

General outline of the study.

This study is part of a training program called “Classes sense fum” framed within the curriculum of ESO. Schools that decide to participate in this training program give their consent so that all their students can participate. The Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and subsequent revisions, and the professional ethics codes were followed during the study. Also, the Spanish law on data confidentiality (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), and the Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights). The school staff informed the parents of the teenagers about the aims of the study and obtained their collaboration.

Study variables

The dependent variables were future smoking intentions and beliefs regarding the RYO cigarettes. Future intentions were studied by asking whether they intended to smoke in the future and if so, whether they would smoke MC or RYO. Beliefs about RYO cigarettes were studied through the degree of agreement for each of the following statements: ‘smoking RYO “hooks” less than smoking MC’, ‘smoking RYO is less harmful than MC because it is more natural’, ‘RYO and MC have nicotine and other harmful components and therefore are equally harmful’, ‘MC has more chemical additives than RYO’ and ‘it's easier to quit smoking for people who smoke RYO rather than the ones who smoke MC’.

The main independent variables were sex, the school year and having smoked at least once in their lifetime. Other variables to describe the sample were smoking frequency and number of cigarettes smoked per day (not having smoked, having smoked a cigarette a day or less, having smoked 2 or more cigarettes a day), both compared to the last 30 days.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of each of the dependent variables according to the independent variables was compared using relative frequencies and Pearson Chi-square test through STATA 15.0 statistical software. In all statistical tests a significance level of 5% was considered.

Results

A total of 111 students participated in the study (100% of the students of 3rd and 4th of ESO). 51.4% of them were girls and 56.8% were enrolled 3rd ESO. 40.5% of surveyed teens had smoked at some time in their life, of these, 34.9% did so every day. 41.9% of users smoked 2 or more cigarettes a day and 39.5% did not smoke during the past 30 days (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bisaura High School student characteristics (Sant Quirze), 2016–19.

| Boy |

Girl |

Total |

p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | % | |

| Course | 0.367 | ||||||

| 3rd | 33 | 61.1 | 30 | 52.6 | 63 | 56.8 | |

| 4th | 21 | 38.9 | 27 | 47.4 | 48 | 43.2 | |

| Having smoked in their lifetime | 0.263 | ||||||

| Yes | 19 | 35.2 | 26 | 45.6 | 45 | 40.5 | |

| No | 35 | 64.8 | 31 | 54.4 | 66 | 59.5 | |

| Frequency ofusea | 0.377 | ||||||

| Every day | 7 | 38.9 | 8 | 32.0 | 15 | 34.9 | |

| One or more times a week or less than once a week | 6 | 33.3 | 5 | 20.0 | 11 | 25.6 | |

| I have not smoked for the last 30 days | 5 | 27.8 | 12 | 48.0 | 17 | 39.5 | |

| Daily smoked cigarettes* | 0.282 | ||||||

| 2 or more cigarettes a day | 8 | 44.4 | 10 | 40.0 | 18 | 41.9 | |

| A cigarette day or less (just a few puffs) | 5 | 27.8 | 3 | 12.0 | 8 | 18.6 | |

| I have not smoked for the last 30 days | 5 | 27.8 | 12 | 48.0 | 17 | 39.5 | |

last 30 days.

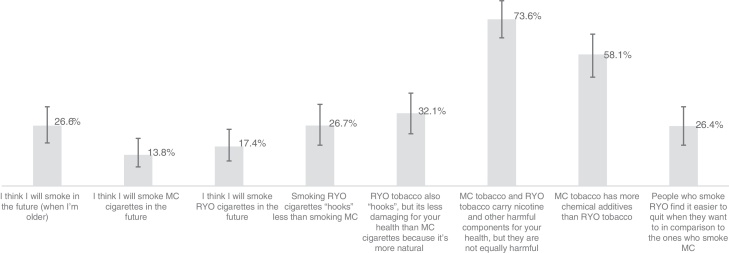

26.6% of adolescents reported that would smoke in the future, 13.8% that would smoke MC and 17.4% RYO (Fig. 2). No statistically significant differences were found by sex or course. Instead, teens who had smoked at least once in their life had higher proportions of intent tobacco consumption in the future (54.5% vs. 7.7%), MC consumption (27.3% vs. 4.6%) and RYO consumption (40.9% vs. 1.5%) than those who had never smoked (p < 0.005) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Bisaura High School student future intentions and beliefs about RYO of the (Sant Quirze), 2016–19.

Table 2.

Dependent variables (future intentions and beliefs about RYO) by sex, school year and according to whether they had ever smoked in life.

| Sex |

Course |

Smoke |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male |

Female |

p Value | 3rd |

4th |

p Value | Have smoked |

Not have smoked |

p Value | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Future intentions regarding smoking | |||||||||||||||

| I think I will smoke in the future (when I’m older) | 0.633 | 0.828 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 13 | 24.5 | 16 | 28.6 | 29 | 46.8 | 13 | 27.7 | 24 | 54.5 | 5 | 7.7 | |||

| No | 40 | 75.5 | 40 | 71.4 | 46 | 74.2 | 34 | 72.3 | 20 | 45.5 | 60 | 92.3 | |||

| I think I will smoke MC cigarettes in the future | 0.202 | 0.41 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 9.4 | 10 | 17.9 | 10 | 16.1 | 5 | 10.6 | 12 | 27.3 | 3 | 4.6 | |||

| No | 48 | 90.6 | 46 | 82.1 | 52 | 83.9 | 42 | 89.4 | 32 | 72.7 | 62 | 95.4 | |||

| I think I will smoke RYO cigarettes in the future | 0.7 | 0.922 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 18.9 | 9 | 16.1 | 11 | 17.7 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 40.9 | 1 | 1.5 | |||

| No | 43 | 81.1 | 47 | 83.9 | 51 | 82.3 | 39 | 83 | 26 | 59.1 | 64 | 98.5 | |||

| Beliefs about RYO tobacco | |||||||||||||||

| Smoking RYO cigarettes “hooks” less than smoking MC | 0.082 | 0.906 | 0.042 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 17 | 34.7 | 11 | 19.6 | 16 | 27.1 | 12 | 26.1 | 16 | 37.2 | 12 | 19.4 | |||

| No | 32 | 65.3 | 45 | 80.4 | 43 | 72.9 | 34 | 73.9 | 27 | 62.8 | 50 | 80.6 | |||

| RYO tobacco also “hooks”, but its less damaging for your health than MC cigarettes because it's more natural | 0.039 | 0.385 | 0.708 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 21 | 42 | 13 | 23.2 | 21 | 35.6 | 13 | 27.7 | 15 | 34.1 | 19 | 30.6 | |||

| No | 29 | 58 | 43 | 76.8 | 38 | 64.4 | 34 | 72.3 | 29 | 65.9 | 43 | 69.4 | |||

| MC tobacco and RYO tobacco carry nicotine and other harmful components for your health, and therefore are equally harmful | 0.927 | 0.854 | 0.288 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 37 | 74 | 41 | 73.2 | 43 | 72.9 | 35 | 74.5 | 30 | 68.2 | 48 | 77.4 | |||

| No | 13 | 26 | 15 | 26.8 | 16 | 27.1 | 12 | 25.5 | 14 | 31.8 | 14 | 22.6 | |||

| MC tobacco has more chemical additives than RYO tobacco | 0.315 | 0.492 | 0.682 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 31 | 63.3 | 30 | 53.6 | 36 | 61 | 25 | 54.3 | 26 | 60.5 | 35 | 56.5 | |||

| No | 18 | 36.7 | 26 | 46.4 | 2.3 | 39 | 21 | 45.7 | 17 | 39.5 | 27 | 43.5 | |||

| People who smoke RYO find it easier to quit when they want to in comparison to the ones who smoke MC | 0.927 | 0.05 | 0.016 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 13 | 26 | 15 | 26.8 | 20 | 33.9 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 38.6 | 11 | 17.7 | |||

| No | 37 | 74 | 41 | 73.2 | 39 | 66.1 | 39 | 83 | 27 | 61.4 | 51 | 82.3 | |||

Regarding beliefs, 26.7%, 32.1% and 26.4% believed that RYO cigarettes produced less addiction, was less harmful to health and it was easier to quit smoking compared to MC, respectively. Furthermore, 58.1% believed that MC had more chemical additives and 73.6% believed that RYO and MC were not equally harmful (Fig. 2). No statistically significant differences by sex or course were found, except in the belief that RYO was less damaging than MC, where 42% of boys thought it was less harmful, compared to 23.2% of girls (p < .005). In the stratified analyzes according to whether they had ever smoked in their life or not, statistically significant differences were found in some beliefs. Among those who smoked, 37.2% believed that RYO is less addictive than MC, and 38.6% believed that quitting RYO is easier than MC, compared to 19.4% and 17.7% of whom had never smoked (Table 2).

Discussion

The main results of the study show that 26.6% of surveyed teens intend to smoke in the future, concretely, 17.4% believe they will smoke RYO. About 30% of teens express at least one favorable misconception regarding RYO. The most reported one was that MC and RYO have nicotine and other components harmful to health, but they are not equally harmful (73.6% of adolescents) and that the MC has more chemical additives than RYO (58.1% of adolescents). Both future intentions and beliefs are statistically significant when associated with having smoked at least once in their lifetime, being those who have ever smoked in their life the ones with greater intention to smoke in the future and greater percentage of erroneous beliefs.

Despite the decreasing trend in smoking, a large number of young people continue with this habit and there are teenagers who start this harmful and addictive consumption very early.1, 22 The results of this study show that 40.5% of the surveyed students have smoked at least once in their life. Of these, 34.9% do it every day and 41.9% smoke 2 cigarettes or more a day. Some of these results agree with those obtained in the last ESTUDES survey,5 which documented that 40.7% of respondents had smoked at least once in their life. Among young people, the proportion of people who use roll-your-own cigarettes (RYO) has grown.3, 4 In our study we found that 26.6% of the respondents intend to smoke in the future, mainly RYO. Intention to smoke in the future has been identified as an important predictor of smoking behavior in adolescents over time, which means its identification can be useful for understanding the smoker's dynamics in adolescence.22

There is a significant proportion of young people with false beliefs regarding RYO and its properties. Specifically, more than 20% of young respondents believe that smoking RYO “hooks” less, that is less damaging than MC and it is easier for RYO smokers to quit than those who smoke MC. Therefore, our study shows that a large percentage of young people have false beliefs about RYO, in line with other studies carried out so far.8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 23 We have seen, for example, that many young people perceive the consumption of RYO as a less harmful way to smoke compared to the use of MC and they believe to have better personal control over consumption.8 However, studies show that are equally harmful or than smoking RYO is even worse than smoking MC.13, 14, 15, 16 We also found significant proportions of surveyed students who believe that RYO cigarettes “hook” less than MC, and that RYO is less harmful because it is more natural, in line with other authors.12, 14, 15, 16, 17 Furthermore, they believe that MC contains more chemical additives than RYO and that RYO smokers find it easier to quit when they want to.9

In line with other studies, we found that the fact of having smoked in life is significantly related to smoking intentions in the future,24 with the intention to smoke MC or RYO in the future, as well as the belief that smoking RYO hooks less than MC and that is easier to quit smoking it. Therefore, experimenting with tobacco consumption in adolescence is a major risk factor to consider and therefore, they should play a major role in smoking prevention programs.24 Behavioral interventions may reduce the proportion that nonsmoking adolescents try,25 but some authors suggest that there is no evidence that educational interventions have any influence in prevalence nor incidence of smoking.26

Although there are some examples of programs with these objectives, such as “Smokeless class”,8 which has shown to reduce false beliefs in teenagers after its evaluation,27 there is a need to continue strengthening, designing and evaluating prevention programs to prevent the onset of tobacco consumption during adolescence and correct false beliefs about RYO. Moreover, a change in the taxation of the tobacco would be desirable to correct the current price of the RYO, which is very low.7, 13, 28, 29

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow to establish causal effects. Another is its sample, specifically in some categories: the results may not be representative of all Catalan adolescents. Larger studies are needed to confirm the results obtained. To gain statistical power, two grades were studied, analyzing students between 14 and 16 years, considering the fact that in this period adolescents start using.5 We do not believe that the academic environment can exert counter pressure when declaring the actual consumption of substances; questions about substance use, consumer beliefs and intentions were self-declared and there are indications that the use of self-reported questionnaires is a reliable method for measuring substance use in adolescents.30

Even though demystification of false beliefs about RYO among adolescents is very important, future interventions should also focus on applying proactive programs in adolescents. Different strategies have proven to be effective in reducing tobacco consumption, passively reducing exposure to tobacco, or on promoting tobacco cessation, some of them are: increasing the price of tobacco products, education through the media, tobacco industry restrictions, use restrictions, access restrictions for underage and community education among others.31

Conclusions

The main conclusions can be summarized in the existence of a significant percentage of young people who intend to smoke in the future and have erroneous beliefs about RYO. There is therefore the need to continue working on activities with an educational and tobacco preventive approach. The information that young people have regarding RYO needs to be improved to correct their misconceptions about RYO, generating a critical analysis process to help prevent future consumption of both RYO and tobacco in general.

What is known on the topic

-

•

Among smokers, especially among young people, the proportion of people who use rolling tobacco has grown.

-

•

The increase can be explained by false beliefs about rolling cigarettes.

-

•

There are currently few studies on adolescent population that smokes rolling cigarettes in our country.

What this study contributes

-

•

There is a significant percentage of young people with future smoking intentions and wrong beliefs about rolling cigarettes.

-

•

These percentages differed depending on whether the teens had ever smoked in their life, their sex and their course.

-

•

The information that young people have about rolling cigarettes needs to be improved in order to correct their wrong beliefs and to generate a process of critical analysis to help prevent future tobacco consumption.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics declarations

This study is part of a training program called “Classes sense fum” framed within the curriculum of ESO. Schools that decide to participate in this training program give their consent so that all their students can participate. The Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and subsequent revisions, and the professional ethics codes were followed during the study. Also, the Spanish law on data confidentiality (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016, on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), and the Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights). The school staff informed the parents of the teenagers about the aims of the study and obtained their collaboration.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students and teachers of the High School Bisaura from Sant Quirze de Besora, whom facilitated the researchers to conduct the study. We also would like to thank M. Rosa Cirera Guàrdia and Helena González-Casals for their help in the various tasks involved in the management of the project. This paper is part of the doctoral dissertation of Eva Codinach-Danés, at the Universitat de Vic – Universitat Central de Catalunya.

References

- 1.Gutiérrez-Abejón E., Rejas-Gutiérrez J., Criado-Espegel P., Campo-Ortega E.P., Breñas-Villalón M.T., Martín-Sobrino N. Smoking impact on mortality in Spain in 2012. Med Clin (Barc) 2015;145:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas . Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2016. Encuesta Sobre Uso de Drogas En Enseñanzas Secundarias En España (ESTUDES), 1994–2014. https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/encuestas_ESTUDES.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu M., Martínez-Sánchez J.M., Clèries R., Villalbí J.R., Daynard R.A., Connolly G.N. Opposite trends in the consumption of manufactured and roll-your-own cigarettes in Spain (1991–2020) BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006552. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarrazo M., Pérez-Ríos M., Santiago-Pérez M.I., Malvar A., Suanzes J., Hervada X. Cambios en el consumo de tabaco: auge del tabaco de liar e introducción de los cigarrillos electrónicos. Gac Sanit. 2017;31:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas . Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2018. Encuesta Estatal Sobre El Uso de Drogas En Enseñanzas Secundarias (ESTUDES) 1994–2018. https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/encuestas_ESTUDES.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia O., Medina A., Schiaffino A. Direcció General de Planificació en Salut; 2018. Enquesta de Salut de Catalunya: Comportaments Relacionats Amb La Salut, l’estat de Salut i l’ús de Serveis Sanitaris a Catalunya. Informe Dels Principals Resultats 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sureda X., Fu M., Martínez-Sánchez J.M., Martínez C., Ballbé M., Pérez-Ortuño R. Manufactured and roll-your-own cigarettes: a changing pattern of smoking in Barcelona, Spain. Environ Res. 2017;155:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larriba-Montull J., Tarifa-Lucea N. Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya; 2016. Fumar? Jo No m’hi Embolico! Unitat Didàctica Sobre El Tabac de Cargolar. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson S.E., Shahab L., West R., Brown J. Roll-your-own cigarette use and smoking cessation behaviour: a cross-sectional population study in England. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e025370. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.María QÁ, Pérez M.C., Fernández I.I., Sánchez M.C.C., García B.C. El consumo y opinión sobre el tabaco de liar en población adolescente de un instituto del área centro de Asturias. RqR Enferm Comun. 2016;4:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young D., Wilson N., Borland R., Edwards R., Weerasekera D. Prevalence, correlates of, and reasons for using roll-your-own tobacco in a high RYO use country: findings from the ITC New Zealand survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:1089–1098. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslin E., Hanafin J., Clancy L. It's not all about price: factors associated with roll-your-own tobacco use among young people – a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:991. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5921-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cartanyà-Hueso À., Lidón-Moyano C., Fu M., Perez-Otunño R., Ballbè M., Matilla-Santander N. Comparison of TSNAs concentration in saliva according to type of tobacco smoked. Environ Res. 2019;172:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoek J., Ferguson S., Court E., Gallopel-Morvan K. Qualitative exploration of young adult RYO smokers’ practices. Tob Control. 2016;26:563–568. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nosa V., Glover M., Min S., Scragg R., Bullen C., McCool J. The use of the “rollie” in New Zealand: preference for loose tobacco among an ethnically diverse low socioeconomic urban population. N Z Med J. 2011;124:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor R.J., McNeill A., Borland R., Hammond D., King B., Boudreau C. Smokers’ beliefs about the relative safety of other tobacco products: findings from the ITC collaboration. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:1033–1042. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young D., Borland R., Hammond D., Cummings K.M., Devlin E., Yong H.H. Prevalence and attributes of roll-your-own smokers in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl. 3):iii76–iii82. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castaño Calduch T., Hebert Jiménez C., Campo San Segundo M.a.T., Ysa Valle M., Pons Carlos-Roca A. Tabaco de liar: una prioridad de salud pública y consumo. Gac Sanit. 2012;26:267–269. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowles J. Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited; 2007. Mainstream smoke emissions from “Roll-Your-Own” loose leaf tobacco sold in New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laugesen M., Epton M., Frampton C.M., Glover M., Lea R.A. Hand-rolled cigarette smoking patterns compared with factory-made cigarette smoking in New Zealand men. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1.) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcilla A., Beltran M.I., Gómez-Siurana A., Berenguer D., Martínez-Castellanos I. Comparison between the mainstream smoke of eleven RYO tobacco brands and the reference tobacco 3R4F. Toxicol Rep. 2014;1:122–136. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao X., White K.M., Young R.M. Future smoking intentions at critical ages among students in two chinese high schools. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s12529-018-09759-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sureda X., Villalbí J.R., Espelt A., Franco M. Living under the influence: normalisation of alcohol consumption in our cities. Gac Sanit. 2017;31:66–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariza i Cardenal C., Nebot i Adell M. Predictores de la iniciación al consumo de tabaco en escolares de enseñanza secundaria de Barcelona y Lleida. Rev Esp Salud Públ. 2002;76:227–238. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272002000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owens D.K., Davidson K.W., Krist A.H., Barry M.J., Cabana M., Caughey A.B. Primary care interventions for prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1590. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valdivieso López E., Rey-Reñones C., Rodriguez-Blanco T., Ferre C., Arija V., Barrera M.L. Efficacy of a smoking prevention programme in Catalan secondary schools: a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Spain: smoking prevention programme in schools. Addiction. 2015;110:852–860. doi: 10.1111/add.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valverde A., Suelves J., Larriba J., Valmayor S., Martínez D., Cabezas C. Actividad educativa para adolescentes sobre el tabaco de liar en Catalunya. Presentación Oral presented at the: XXXVI reunión científica de la sociedad española de epidemiología y XIII congresso da associação portuguesa de epidemiologia; Lisboa; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown A.K., Nagelhout G.E., van den Putte B., Willemsen M.C., Mons U., Guignard R. Trends and socioeconomic differences in roll-your-own tobacco use: findings from the ITC Europe Surveys. Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl. 3):iii11–iii16. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornelsen L., Normand C. Is roll-your-own tobacco substitute for manufactured cigarettes: evidence from Ireland? J Public Health (Oxf) 2014;36:65–71. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engs R., Hanson D. Gender differences in drinking patterns and problems among college students: a review of the literature. JADE. 1990;35:36–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopkins D.P., Briss P.A., Ricard C.J., Husten C.G., Carande-Kulis V.G., Fielding J.E. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 2001:16–66. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]