Abstract

Background

ESRD is considered an irreversible loss of renal function, yet some patients will recover kidney function sufficiently to come off dialysis. Potentially modifiable predictors of kidney recovery, such as dialysis prescription, have not been fully examined.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study using United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data to identify incident hemodialysis (HD) patients between 2012 and 2016, the first 4 years for which dialysis treatment data is available. The primary outcome was kidney recovery within 1 year of ESRD and HD initiation, defined by a specific recovery code and survival off dialysis for at least 30 days. Patient and treatment characteristics were compared between those that recovered versus those that remained dialysis-dependent. A time-dependent survival model was used to identify independent predictors of kidney recovery.

Results

During the study period, there were 372,387 incident HD patients with available data, among whom 16,930 (4.5%) recovered to dialysis-independence. Compared to non-recovery, a higher proportion of patients with kidney recovery were of white race, and non-Hispanic ethnicity. Both groups had a similar age distribution. Patients with an acute kidney injury diagnosis as primary cause of ESRD were most likely to recover, but the most common ESRD diagnosis among recovering patients was type 2 diabetes (29.8% of recovery cases). Higher eGFR and lower albumin at ESRD initiation were associated with increased likelihood of recovery. When examining HD ultrafiltration rate (UFR), each quintile above the first quintile was associated with a progressively lower likelihood of recovery (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.43–0.48 for highest versus lowest quintile, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

We identified non-modifiable and potentially modifiable factors associated with kidney recovery which may assist clinicians in counseling and monitoring incident ESRD patients with a greater chance to gain dialysis-independence. Clinical trials are warranted to examine the impact of dialysis prescription on subsequent kidney function recovery.

Keywords: End-stage renal disease, Acute kidney injury, Kidney recovery, Risk factors

Background

By definition, a diagnosis of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) indicates that patients have irreversibly lost kidney function to the point of requiring dialysis or transplantation. Yet a proportion of such patients will in fact recover kidney function sufficient to come off dialysis, at least for a period of time – as high as 5–6% of incident ESRD patients in recent years [1, 2]. Dialysis-independence is a critically important and highly patient-centered outcome for dialysis patients, but there are currently no tools to help clinicians more accurately identify which patients are most likely to recover.

Because ESRD designation is a clinical determination, it remains prone to some inherent imprecision. Identification of patient factors associated with recovery can help guide both patient and provider expectations and assist in monitoring for recovery. This can be important because kidney function recovery in the dialysis center may not be recognized if not actively searched for. In many dialysis centers, it is not routine to assess residual kidney function and therefore any improvement in kidney function may be missed. Under-recognition of recovery can result in patients remaining on dialysis longer than necessary.

Perhaps even more importantly, there is a need to identify clinical practices – including dialysis prescription – that may influence (either positively or negatively) the chances of kidney recovery. The potential negative impacts of hemodialysis therapy on cardiac and neurologic function have been well-described [3, 4], and this may translate to exacerbating kidney injury when kidney recovery is still possible. Dialysis treatment factors have not been examined in the context of ESRD recovery, in part because of limited availability of such data. However, in 2012, mandatory reporting of some clinical treatment data from U.S. dialysis centers began through the Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web Enabled Network (CROWNWeb) application, providing an opportunity to examine dialysis prescription factors with outcomes on a national level.

The goal of this study was to identify ESRD patient characteristics and hemodialysis prescription factors associated with subsequent kidney function recovery, with the hope of informing current practices as well as laying the foundation for further research into optimizing treatment approaches in this patient population.

Methods

Data sources and patient population

The United States Renal Data System (USRDS) collects, analyzes, and distributes information about chronic kidney disease (CKD) and ESRD in the United States. The USRDS data sources include Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), and selected clinical and administrative data reported monthly by all Medicare-certified dialysis facilities in the U.S. (CROWNWeb). Data from these sources are merged together to create a treatment history file of ESRD treatment for each patient [5, 6]. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board with a waiver of consent due to the retrospective nature and use of de-identified datasets (HUM00086162).

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of incident ESRD patients on dialysis in the U.S. We identified patients with kidney recovery by ESRD initiation year from 1996 through 2016 in order to describe trends. We then focused the cohort analysis on patients starting maintenance hemodialysis (HD) between May 1st, 2012 and May 31st, 2016, representing the initial period for which CROWNWeb treatment data became available. Patient treatments were followed through May 31st, 2017, allowing at least 1-year of follow-up on all patients. Patient demographic information, including age, sex, race, and ethnicity were obtained from USRDS 2017 Standard Analysis Files (SAF). Additional clinical information, such as pre-ESRD laboratory data, insurance coverage, cause of ESRD and pre-ESRD care, were obtained from the ESRD medical evidence Form (CMS Form 2728).

Hemodialysis treatment data was obtained from CROWNWeb. Data are reported to CROWNWeb on a once-monthly data and represent the findings from a single treatment, as opposed to the average of all monthly treatments. Dialysis ultrafiltration rate (UFR) was calculated as (pre-HD weight – post-HD weight)/(post-HD weight)/(treatment time) for each month since ESRD initiation. The mean UFR of the first 12 months was grouped into quintiles and used in the descriptive analysis. The monthly UFR was also grouped into separate quintiles and used in the time-dependent model.

Our primary outcome was recovery to dialysis independence within 1 year of ESRD initiation. ESRD recovery events were identified by the recovery of kidney function code in the USRDS patient event file, and patients had to survive at least 30 days without receiving additional dialysis or undergoing kidney transplantation. This parameter was an effort to exclude patients that were withdrawn from dialysis. Of note, there is a separate specific code to denote withdrawal from dialysis for palliative care reasons.

Statistical approach

Patient characteristics were compared between patients that did versus did not recover kidney function to dialysis independence within 1 year. An unadjusted Cox model was conducted for each predictor, with censoring for death.

Time dependent Cox regression analysis was performed to estimate the relationship of predictors with the primary outcome of recovery to dialysis independence within 1 year. To account for potential changes in dialysis prescription over the time period, UFR was used as a time-varying covariate. We generated a counting process data, in which each patient is represented by one row, and each row represents a 1 month interval during which the UFR could be changed while all other covariates remain constant.

Results

ESRD recovery trends

From 1996 through 2016 there were 2,166,429 incident dialysis patients, of whom 104,250 (4.8%) experienced kidney recovery. Over these 2 decades, the crude cumulative incidence of recovery increased gradually from 2.7% in 1996 to a peak of 6.3% in 2010, before decreasing the past several years (Table 1). Even with this recent trend, the cumulative incidence of recovery from the 5 most recent years represents a 91% increase in recovery compared to the first 5 years of the study period. The majority of recovering patients (62.5%) did so within the first 3 months after dialysis initiation.

Table 1.

Trends in ESRD recovery, from 1996 to 2016

| Patients with Recovery by time from Dialysis Initiation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Incident ESRD Patients | 0–3 months |

4–12 months |

Total within 1 year | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1996 | 75,038 | 1138 | 1.52% | 864 | 1.15% | 2002 | 2.67% |

| 1997 | 80,075 | 1323 | 1.65% | 952 | 1.19% | 2275 | 2.84% |

| 1998 | 85,140 | 1381 | 1.62% | 1016 | 1.19% | 2397 | 2.82% |

| 1999 | 88,735 | 1560 | 1.76% | 1084 | 1.22% | 2644 | 2.98% |

| 2000 | 92,076 | 1749 | 1.90% | 1294 | 1.41% | 3043 | 3.30% |

| 2001 | 95,763 | 2008 | 2.10% | 1278 | 1.33% | 3286 | 3.43% |

| 2002 | 97,892 | 2277 | 2.33% | 1538 | 1.57% | 3815 | 3.90% |

| 2003 | 100,145 | 2407 | 2.40% | 1650 | 1.65% | 4057 | 4.05% |

| 2004 | 101,613 | 2661 | 2.62% | 1762 | 1.73% | 4423 | 4.35% |

| 2005 | 103,751 | 2961 | 2.85% | 1938 | 1.87% | 4899 | 4.72% |

| 2006 | 107,192 | 3167 | 2.95% | 2096 | 1.96% | 5263 | 4.91% |

| 2007 | 107,176 | 3726 | 3.48% | 2259 | 2.11% | 5985 | 5.58% |

| 2008 | 108,707 | 4099 | 3.77% | 2249 | 2.07% | 6348 | 5.84% |

| 2009 | 112,300 | 4366 | 3.89% | 2530 | 2.25% | 6896 | 6.14% |

| 2010 | 112,609 | 4426 | 3.93% | 2700 | 2.40% | 7126 | 6.33% |

| 2011 | 110,420 | 4211 | 3.81% | 2498 | 2.26% | 6709 | 6.08% |

| 2012 | 112,312 | 4496 | 4.00% | 2505 | 2.23% | 7001 | 6.23% |

| 2013 | 115,070 | 4687 | 4.07% | 2351 | 2.04% | 7038 | 6.12% |

| 2014 | 117,954 | 4413 | 3.74% | 2154 | 1.83% | 6567 | 5.57% |

| 2015 | 121,471 | 4313 | 3.55% | 2263 | 1.86% | 6576 | 5.41% |

| 2016 | 120,990 | 3746 | 3.10% | 2154 | 1.78% | 5900 | 4.88% |

| Total | 2,166,429 | 65,115 | 3.01% | 39,135 | 1.81% | 104,250 | 4.81% |

ESRD End-stage renal disease

Patient characteristics

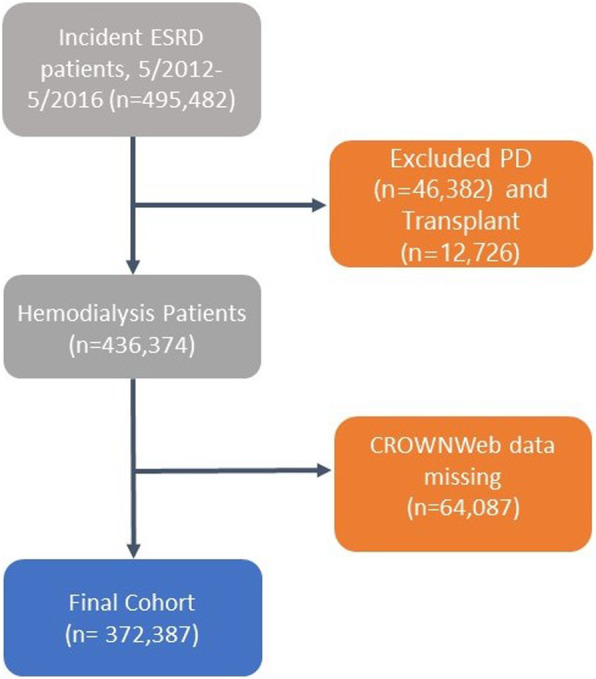

Between May 2012 and May 2016, we identified 372,387 incident HD patients for whom CROWNWeb data was available (Fig. 1). Among these, 16,930 (4.5%) recovered to dialysis independence within 1 year. Patient characteristics at time of ESRD incidence are shown in Table 2. A slightly higher proportion of men compared to women experienced recovery. White patients had the highest cumulative incidence of recovery at 5.4%, while 2.9% of Black patients recovered. Diagnoses of diabetes, congestive heart failure and cerebrovascular disease were each associated with lower likelihood of recovery. Evidence of prior nephrology care (such as prior use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or nephrology visits) was associated with lower likelihood of recovery.

Fig. 1.

Derivation of analytic cohort

Table 2.

Patient characteristics by ESRD recovery status

| All Patients | Patients With Recovery | Patients Without Recovery | Univariate Cox model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 372,387 | 16,930 | 355,457 | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 214,906 | 9980 (4.6%) | 204,926 (95.4%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Female | 157,481 | 6950 (4.4%) | 150,531 (95.6%) | 0.95 | 0.92, 0.98 | 0.0013 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 247,388 | 13,306 (5.4%) | 234,082 (94.6%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Black | 102,499 | 3013 (2.9%) | 99,486 (97.1%) | 0.53 | 0.50, 0.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Native American | 3541 | 98 (2.8%) | 3443 (97.2%) | 0.49 | 0.40, 0.60 | < 0.0001 |

| Asian | 13,675 | 368 (2.7%) | 13,307 (97.3%) | 0.48 | 0.43, 0.53 | < 0.0001 |

| Pacific Islander | 4413 | 100 (2.3%) | 4313 (97.7%) | 0.40 | 0.33, 0.48 | < 0.0001 |

| Other/unknown | 871 | 45 (5.2%) | 826 (94.8%) | 0.96 | 0.71, 1.28 | 0.76 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 372,387 | 63.0 (14.3) | 63.4 (14.8) | 1.001 | 1.00, 1.002 | 0.29 |

| Age in years (category) | ||||||

| 0–44 | 40,796 | 1835 (4.5%) | 38,961 (95.5%) | ref | ref | Ref |

| 45–64 | 143,006 | 6524 (4.6%) | 136,482 (95.4%) | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.09 | 0.26 |

| 65+ | 188,585 | 8571 (4.5%) | 180,014 (95.5%) | 1.08 | 1.02, 1.13 | 0.004 |

| Primary ESRD cause (category) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 179,438 | 5429 (3%) | 174,009 (97%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Hypertension | 112,091 | 3945 (3.5%) | 108,146 (96.5%) | 1.18 | 1.13, 1.22 | < 0.0001 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 25,493 | 1381 (5.4%) | 24,112 (94.6%) | 1.78 | 1.68, 1.89 | < 0.0001 |

| Cystic Kidney | 6286 | 70 (1.1%) | 6216 (98.9%) | 0.34 | 0.28, 0.45 | < 0.0001 |

| Other Urologic | 4776 | 262 (5.5%) | 4514 (94.5%) | 1.82 | 1.64, 2.10 | < 0.0001 |

| Other Cause | 34,961 | 4645 (13.3%) | 30,316 (86.7%) | 4.92 | 4.73, 5.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown Cause | 7868 | 661 (8.4%) | 7207 (91.6%) | 2.96 | 2.73, 3.20 | < 0.0001 |

| Missing Cause | 1474 | 537 (36.4%) | 937 (63.6%) | 17.85 | 16.33, 19.50 | < 0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 219,004 | 8197 (3.7%) | 210,807 (96.3%) | 0.64 | 0.62, 0.67 | < 0.0001 |

| Atherosclerotic Heart Disease | 58,333 | 2573 (4.4%) | 55,760 (95.6%) | 0.99 | 0.95, 1.03 | 0.60 |

| Heart Failure | 113,142 | 4560 (4.0%) | 108,582 (96.0%) | 0.87 | 0.84, 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 326,100 | 12,978 (4.0%) | 313,122 (96.0%) | 0.44 | 0.43, 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 42,162 | 1947 (4.6%) | 40,215 (95.4%) | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 | 0.07 |

| COPD | 36,486 | 2038 (5.6%) | 34,448 (94.4%) | 1.32 | 1.26, 1.38 | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 26,453 | 1640 (6.2%) | 24,813 (93.8%) | 1.50 | 1.42, 1.58 | < 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 32,996 | 1348 (4.1%) | 31,648 (95.9%) | 0.90 | 0.85, 0.95 | 0.0003 |

| Pre-ESRD ESA Use | < 0.0001 | |||||

| No | 205,728 | 10,216 (5%) | 195,512 (95%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Yes | 51,895 | 1103 (2.1%) | 50,792 (97.9%) | 0.42 | 0.39, 0.45 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 114,764 | 5611 (4.9%) | 109,153 (95.1%) | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.03 | 0.67 |

| Pre-ESRD Nephrologist care | ||||||

| No | 95,181 | 7832 (8.2%) | 87,349 (91.8%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Yes | 223,610 | 5645 (2.5%) | 217,965 (97.5%) | 0.29 | 0.28, 0.30 | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 53,596 | 3453 (6.4%) | 50,143 (93.6%) | 0.78 | 0.75, 0.82 | < 0.0001 |

| Insurance Coverage | ||||||

| Medicare only | 110,954 | 5096 (4.6%) | 105,858 (95.4%) | ref | ref | ref |

| Employer only | 41,771 | 1953 (4.7%) | 39,818 (95.3%) | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 | 0.27 |

| Medicaid only | 46,707 | 1854 (4%) | 44,853 (96%) | 0.83 | 0.78, 0.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 54,724 | 2087 (3.8%) | 52,637 (96.2%) | 0.82 | 0.78, 0.86 | < 0.0001 |

| Medicare and employer | 22,187 | 994 (4.5%) | 21,193 (95.5%) | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.03 | 0.30 |

| Medicare and other | 46,250 | 2252 (4.9%) | 43,998 (95.1%) | 1.08 | 1.02, 0.13 | 0.004 |

| None | 30,019 | 1788 (6%) | 28,231 (94%) | 1.26 | 1.20, 1.33 | < 0.0001 |

| Other only | 19,775 | 906 (4.6%) | 18,869 (95.4%) | 0.96 | 0.90, 1.03 | 0.30 |

| Lab values at ESRD Initiation | ||||||

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 370,847 | 5.7 (3.8) | 6.7 (10.3) | 0.96 | 0.9, 0.91 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 367,099 | 11.7 (5.6) | 10.1 (4.6) | 1.07 | 1.07, 1.07 | < 0.0001 |

| Serum Albumin (g/dL) | 251,335 | 3 (2.3) | 3.2 (3.2) | 0.73 | 0.71, 0.75 | < 0.0001 |

ESRD End-stage renal disease, ESA Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, eGFR Estimated glomerular filtration rate, COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In terms of primary etiology for ESRD, the diagnostic categories with the highest cumulative incidence of recovery were “missing cause” (36.4%) and “other cause” (which includes acute tubular necrosis; 13.3%). When looking at specific diagnoses, the top 4 diagnoses by proportion of recovery were forms of acute kidney injury (AKI), each with > 20% of patients recovering (Table 3). Combined, these 4 diagnoses contributed to 16.0% of all recovery patients. Conversely, by absolute numbers the top ESRD diagnoses from which patients recovered were type 2 diabetes and hypertension, which together accounted for 51.9% of all recovery patients.

Table 3.

Top diagnoses listed as primary cause of ESRD in patients with kidney function recovery, ranked by proportion and by absolute numbers

| By Proportion Recovering | By Absolute Numbers Recovering | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Total | Recovering | Diagnosis | Total | Recovering |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 783 | 215 (27.5%) | Diabetes Type 2 | 165,263 | 5046 (3.1%) |

| Postinfectious glomerulonephritis | 256 | 64 (25.0%) | Hypertension, unspecified | 108,470 | 3738 (3.4%) |

| Tubular necrosis (no recovery) | 10,099 | 2359 (23.4%) | Tubular necrosis (no recovery) | 10,099 | 2359 (23.4%) |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | 313 | 68 (21.7%) | Missing or Uncertain | 9053 | 1167 (12.9%) |

CROWNWeb data and treatment characteristics

Following dialysis initiation, albumin, calcium and hemoglobin were similar between patients that recovered versus did not recover (Table 4). Patients without recovery had higher phosphorus and parathyroid hormone levels. Patients without recovery also had higher monthly doses of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and were more likely to have received intravenous iron supplementation. With regards to dialysis vascular access, a higher proportion of patients who had a catheter recovered than those with an arteriovenous fistula or graft (5.8% versus 1.0%, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Patient treatment characteristics and laboratory data as reported in CROWNWeb, by recovery status

| Variablea | All | Patients With Recovery (n = 16,930) | Patients Without Recovery (n = 355,457) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) or Proportion | N | Mean (SD) or Proportion | N | Mean (SD) or Proportion | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 353,182 | 3.5 (0.5) | 16,012 | 3.4 (0.5) | 337,170 | 3.5 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 355,196 | 8.8 (0.6) | 16,226 | 8.9 (0.6) | 338,970 | 8.8 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 357,569 | 10.4 (1.0) | 16,365 | 10.3 (1.2) | 341,204 | 10.4 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| ESA monthly dose (units) | 299,143 | 43,949 (40196) | 12,284 | 39,733 (40193) | 286,859 | 44,130 (40187) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin | 342,910 | 460 (328) | 15,232 | 533 (373) | 327,678 | 458 (325) | < 0.001 |

| Iron % saturation | 349,400 | 24.1 (8.8) | 15,769 | 23 (10.1) | 333,631 | 24.1 (8.8) | < 0.001 |

| IV Iron administration | |||||||

| Yes | 212,999 | 59.7% | 8534 | 52.7% | 204,465 | 60.0% | < 0.001 |

| No | 144,016 | 40.3% | 7647 | 47.3% | 136,369 | 40.0% | |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 356,401 | 4.8 (1.2) | 16,288 | 4.1 (1.0) | 340,113 | 4.8 (1.2) | < 0.001 |

| Parathyroid Hormone (pg/mL) | 83,940 | 367 (314) | 3755 | 221 (187) | 80,185 | 374 (317) | < 0.001 |

| Vascular Access Type | < 0.001 | ||||||

| AVF/AVG | 87,996 | 24.3% | 915 | 5.5% | 87,081 | 25.2% | |

| Catheter | 255,931 | 70.8% | 14,817 | 89.4% | 241,114 | 69.9% | |

| Other | 17,819 | 4.9% | 837 | 5.1% | 16,982 | 4.9% | |

| Treatment time per session (minutes) | 335,737 | 223 (28) | 15,996 | 219 (29) | 319,741 | 223 (28) | < 0.001 |

| Single pool Kt/V | 353,328 | 1.5 (0.3) | 16,101 | 1.5 (0.3) | 337,227 | 1.5 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Normalized protein catabolic rate (g/kg/d) | 270,580 | 0.8 (0.2) | 10,943 | 0.70 (0.2) | 259,637 | 0.8 (0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-HD weight (kg) | 335,856 | 84.3 (23.9) | 16,004 | 85.8 (24.7) | 319,852 | 84.2 (23.8) | < 0.001 |

| Post-HD weight (kg) | 335,855 | 82.3 (23.5) | 16,004 | 84.2 (24.3) | 319,851 | 82.2 (23.4) | < 0.001 |

| Mean ultrafiltration rate (ml/kg/hr) | 372,271 | 6.9 (3.1) | 16,920 | 5.4 (3.5) | 355,351 | 7.0 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile of ultrafiltration rate | < 0.001 | ||||||

| 1st (lowest) (<=4.3) | 74,454 | 20.0% | 6779 | 40.1% | 67,675 | 19.0% | |

| 2nd (> 4.3–5.9) | 74,454 | 20.0% | 3369 | 19.9% | 71,085 | 20.0% | |

| 3rd (> 5.9–7.3) | 74,455 | 20.0% | 2558 | 15.1% | 71,897 | 20.2% | |

| 4th (> 7.3–9.1) | 74,454 | 20.0% | 2117 | 12.5% | 72,337 | 20.4% | |

| 5th (> 9.1) | 74,454 | 20.0% | 2097 | 12.4%% | 72,357 | 20.4% | |

ESA Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (includes all forms of ESA but predominantly epoeitin alfa during study period), AVF Arteriovenous fistula, AVG Arteriovenous graft, HD Hemodialysis. Note: collection of parathyroid hormone data in CROWNWeb ceased in April 2014

aLaboratory values are reported as the mean (SD) for continuous variables, and as a proportion for categorical variables. Data is aggregated for the first 3 months after dialysis initiation

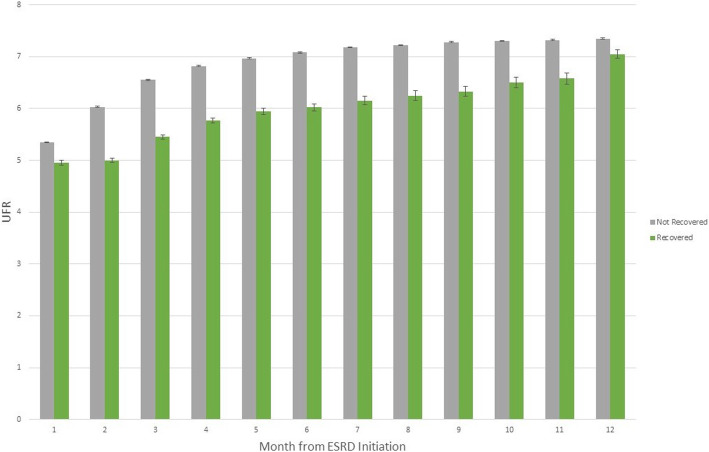

Dialysis treatment time per session was clinically similar between the recovery and non-recovery groups, as was single pool Kt/V. Pre- and post-dialysis weight were slightly higher in the recovery group compared to the non-recovery group. Mean UFR was significantly higher in the non-recovery group compared to the recovery group (7.0 vs 5.4 mL/kg/hr., p < 0.001). When categorized into quintiles, the proportion of patients recovering kidney function decreased with increasing quintile of UFR, ranging from 9.1 to 2.8% from lowest to highest quintile respectively (Table 4). When looking at monthly values, UFR was consistently lower in patients who eventually experienced recovery within 1 year compared to those that did not recover (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean ultrafiltration (UFR) rate by month, stratified by kidney function recovery

In the adjusted model (Table 5), higher UFR over time remained significantly associated with lower likelihood of recovery. There was a stepwise reduction in hazard for recovery with each increasing quintile of UFR. Compared to the lowest quintile, patients with UFR in the top quintile had a 59% lower likelihood of recovery (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.38–0.43). Higher eGFR was associated with recovery. Serum albumin was no longer a significant predictor. Calcium (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.23–1.31), phosphorus (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.56–0.58) and hemoglobin (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.93–0.97) were all significantly associated with recovery.

Table 5.

Multivariate time-dependent model for kidney recovery among incident hemodialysis patients

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (ref = “male”) | ||

| Female | 0.96 (0.92,1.00) | 0.050 |

| Race (ref = “White”) | ||

| Black | 0.49 (0.47,0.52) | < 0.001 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.62 (0.48,0.80) | 0.0003 |

| Asian | 0.64 (0.56,0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Native Hawaii/Pacific Islander | 0.57 (0.44,0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 0.63 (0.39,1.01) | 0.055 |

| Age, years (ref = “0–44”) | ||

| 45–64 | 0.93 (0.86,1.00) | 0.003 |

| 65+ | 0.74 (0.68,0.80) | < 0.001 |

| Primary cause by category (ref = “Diabetes”) | ||

| Cystic Kidney | 0.46 (0.35,0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1.82 (1.68,1.97) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.12 (1.11,1.25) | < 0.001 |

| Missing Cause | 7.41 (4.03,13.62) | < 0.001 |

| Other Cause | 3.37 (3.17,3.57) | < 0.001 |

| Other Urologic | 1.52 (1.30,1.76) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown Cause | 2.02 (1.81,2.26) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.94 (0.90,0.99) | 0.02 |

| Atherosclerotic Heart Disease | 0.97 (0.92,1.03) | 0.28 |

| Heart Failure | 1.20 (1.14,1.25) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.23 (1.17,1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 0.89 (0.83,0.94) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 0.83 (0.79,0.89) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.01 (0.95,1.08) | 0.70 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1.07 (1.00,1.15) | 0.04 |

| Institutionalized | 0.95 (0.89,1.01) | 0.10 |

| Pre-ESRD ESA Use (ref = “no”) | ||

| Yes | 0.69 (0.63,0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.06 (1.01,1.12) | 0.03 |

| Pre-ESRD Nephrologist care (ref = “no”) | ||

| Yes | 0.34 (0.32,0.35) | < 0.0001 |

| Unknown | 0.69 (0.64,0.73) | < 0.0001 |

| Insurance Coverage (ref = “Medicare only”) | ||

| Employer only | 1.06 (0.99,1.15) | 0.12 |

| Medicaid only | 0.89 (0.83,0.96) | 0.003 |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 0.85 (0.80,0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Medicare and employer | 0.99 (0.91,1.08) | 0.86 |

| Medicare and other | 1.01 (0.95,1.08) | 0.68 |

| None | 0.95 (0.88,1.03) | 0.25 |

| Other only | 0.94 (0.86,1.03) | 0.20 |

| Laboratory values | ||

| Serum Creatinine (per mg/dL) | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.86 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 1.05 (1.04,1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Calcium (per mg/dL) | 1.26 (1.22,1.31) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (per g/dL) | 0.99 (0.95,1.04) | 0.72 |

| Phosphorus (per mg/dL) | 0.57 (0.56,0.58) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (per g/dL) | 0.95 (0.93,0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile of ultrafiltration rate (ref = ‘1st/lowest’) | ||

| 2nd | 0.70 (0.67,0.74) | < 0.001 |

| 3rd | 0.58 (0.55,0.62) | < 0.001 |

| 4th | 0.50 (0.47,0.53) | < 0.001 |

| 5th (highest) | 0.41 (0.38,0.43) | < 0.001 |

ESRD End-stage renal disease, ESA Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, eGFR Estimated glomerular filtration rate

Discussion

Over the past two decades there has been a marked overall increase in kidney function recovery among incident ESRD patients. In this national analysis of USRDS data that included a first examination of CROWNWeb data in this context, we identified clinical characteristics and potentially modifiable treatment factors associated with recovery to dialysis independence, a highly relevant, patient-centered outcome. Our findings can help clinicians appropriately risk stratify incident ESRD patients.

We identified several factors associated with kidney recovery, including demographic factors such as female sex and younger age. Most notably, the primary ESRD diagnoses associated with the greatest likelihood of kidney recovery were acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and post-infectious glomerulonephritis – each with 20% or higher recovery. Although non-modifiable, these characteristics can help clinicians risk stratify for the purposes of both monitoring and potentially changing management. For patients most likely to recover, clinicians may choose to defer declaration of ESRD in favor of continued observation for recovery, which has been made easier by the implementation of the Trade Bill allowing AKI related maintenance dialysis at ESRD facilities [7]. In these cases, clinicians may apply recently proposed protocols emphasizing closer monitoring of residual kidney function and increased attention to intradialytic hemodynamic stability [8]. Patients with a favorable recovery profile should be properly educated about signs of kidney recovery and avoidance of potential nephrotoxic exposures. Risk stratification is also important to identify those least likely to recover. Examples include earlier placement of an arteriovenous fistula for vascular access, or earlier referral for transplant evaluation. Thus, accurate risk assessment allows both the opportunity to optimize likelihood of recovery and also the efficient use of resources for those unlikely to recover.

While AKI-related primary diagnoses had the highest cumulative incidence of recovery, they accounted for only about 20% of all recovering ESRD patients. Conversely, patients with ESRD attributed to type 2 diabetes and hypertension comprised slightly more than 50% of all ESRD patients who recovered. Presumably, these patients had an AKI component on top of other comorbidities that was either unrecognized or underestimated. Importantly, when completing the CMS 2728 ESRD certification form, clinicians are only able to pick one primary diagnosis as the cause of ESRD. Further, there is inherent subjectivity in choosing the primary diagnosis, which can predispose to inaccuracies [9]. If an underlying AKI is a component of those who recover, this might not be reported and thus overlooked by clinicians. This oversight might further be accentuated in the transition from hospital to ESRD facilities providing dialysis treatment. Clinically, there is a need to better identify this AKI component in order to recognize the potential for recovery. One possible systems-based solution could be to add a “secondary diagnosis” field to the ESRD certification form, where an acute component could be identified. This change might allow clinicians to identify and treat those with an underlying AKI with a more comprehensive approach. The use of a secondary diagnosis might also improve the handoff between hospital and ESRD facilities.

Another area that warrants further inquiry is the apparent racial inequality in recovery. After adjusting for other characteristics, all race groups had a decreased recovery of kidney function when compared to white patients; this difference was most pronounced with Black patients, who had a 51% lower likelihood of recovery. There are a few possible explanations for this finding. Biologically, the high risk alleles of the APOL1 gene have been implicated in the excess risk for ESRD observed in Black compared to white patients [10]. Although a link between APOL1 and AKI has not been established, [11] it is conceivable that a severe AKI episode could accelerate an underlying ESRD predisposition in high risk patients. Beyond genetic explanation, it is important to discuss the impact of health inequality, and perhaps even unconscious bias, affecting this population. Knowing that Black patients are generally more likely to have ESRD, providers may be predisposed to overlooking the possibility of recovery and/or have a lower threshold for designating a patient as ESRD in the first place. Patient recovery may also be affected by socioeconomic disparities manifested by lower health literacy and education levels. Social determinants of health disproportionately affect Black patients, and have been shown to be prevalent factors in those with kidney disease [12]. Previous studies have also demonstrated a link between lower health literacy and adverse outcomes in patients with CKD and ESRD [13]. Further evaluation is needed to explore the role of social determinants of health in kidney recovery, as these may represent an important opportunity to help reduce the racial disparities observed in our study.

In this study, which to the best of our knowledge is the first exploration of dialysis treatment data available in the USRDS and recovery, we found that higher quintiles of UFR were associated with a progressively lower likelihood of kidney recovery. Being an observational study, we cannot derive a causal relationship between UFR and kidney recovery, especially since CROWNWeb does not capture potentially important confounders such as residual kidney function and urine output. Nonetheless, higher UFR is a well-established risk factor for intradialytic hemodynamic instability [14] which can contribute to organ perfusion damage, providing a plausible mechanism for hindering kidney recovery. Indeed, several studies have reported an association between higher UFR and risk for adverse outcomes such as cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients [15, 16]. A recent study linked higher UFR with both higher mortality and greater loss of residual kidney function; notably, this risk was increased even at UFR values of 6–10 mL/kg/hr. when compared to < 6 mL/kr/hr [17]. Lower UFR values (< 10 mL/kg/hr) have traditionally been considered somewhat “safe”, which emphasizes the importance of monitoring hemodynamic variables. Indeed, a single-center study of patients with AKI requiring outpatient dialysis similarly noted that more frequent episodes of intradialytic hypotension were associated with lower likelihood of recovery to dialysis independence [18]. Our findings build upon this literature by identifying higher UFR as an important and potentially modifiable risk factor for kidney function non-recovery among incident ESRD patients.

Due to the increased recognition of the harms of intradialytic hypotension and link with higher UFR, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted UFR as a reporting quality measure beginning in 2020 [19]. Our findings further highlight the importance of this component of dialysis prescription and would seem to support the recommendations from the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative’s recently published “WATCH-ME” protocol: Weight assessment, Access, Teaching (patient education), Clearance (assessment of residual kidney function), Hypotension avoidance, and Medication review [8]. This protocol emphasizes the importance of weight management and avoidance of hypotension through permissive hypervolemia if necessary. Of note, excessive hypervolemia has also been associated with worse outcomes, [20] so a balance of these extremes is key in weight management for these patients. Whether application of these principles to incident ESRD patients who are more likely to recover kidney function may result in increased recovery has not been evaluated. However, observational studies have noted that facilities with protocols specifically aimed at reducing intradialytic hemodynamic instability are associated with improved patient outcomes compared to facilities without such protocols [21]. In particular, patients with a primary ESRD diagnosis of AKI require close observation for evidence of renal recovery, and more attention to weight changes and hypotension might provide a good starting point.

There are several limitations to our study. Most notably, the observational design and lack of data on residual kidney function and urine volume limit any causal inferences between the observed higher UF rates and lower likelihood of renal recovery. Nonetheless, our findings are plausible and in line with expert guidelines regarding optimal approaches to dialysis prescription in patients with AKI. We encourage dialysis organizations which have access to more granular treatment data to further explore and confirm our study’s findings. Another limitation is the inherent subjectivity in determining ESRD status and assigning a primary cause of this diagnosis. It is not feasible to do a nephrologist-level analysis, but it is conceivable that individual practice patterns could significantly influence recovery rates. Our study period was prior to recent regulatory changes (i.e. passage of the Trade Bill as discussed above) which have potentially significantly changed the approach to ESRD diagnosis in patients with AKI; future analyses are needed to assess the impact of these changes. Lastly, our primary outcome of kidney function recovery may have incomplete ascertainment due to lack of recognition. We hope that the results of this study will increase awareness of the potential for recovery and reduce any missed opportunities.

Conclusions

Nearly 1 in 20 incident ESRD patients will recover to dialysis independence within 1 year. In this study we identified several predictors of kidney recovery, including a potential link between higher ultrafiltration rate and reduced likelihood of recovery. Clinicians can use this information to risk stratify patients and consider delaying ESRD designation and/or closer monitoring for recovery, particularly among patients with a primary ESRD diagnosis in an AKI category.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- CROWNWeb

Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web Enabled Network

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- HD

Hemodialysis

- UFR

Ultrafiltration rate

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- USRDS

United States Renal Data System

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study. HY and DS performed primary analysis of the data. MS, RS and MH provided interpretation of the data. MS and MH drafted the manuscript and all authors provided critical revisions and final approval for publication. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), which is funded by the National Institute of Digestive and Diabetes and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), through National Institutes of Health (NIH) contract HHSN276201400001C. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), which is a publicly available data source. Requests for datasets can be made at https://usrds.org/for-researchers/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board (HUM00086162). The need for informed consent was waived by the University of Michigan institutional review board due to the retrospective nature and use of de-identified datasets. The authors confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mohan S, Huff E, Wish J, Lilly M, Chen SC, McClellan WM. Fistula first breakthrough initiative data C: recovery of renal function among ESRD patients in the US medicare program. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BJ, Johansen KL, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Potential impact of medicare payment policy on misclassification of dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury as ESRD: a national temporal trend analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(2):311–313. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre CW. Recurrent circulatory stress: the dark side of dialysis. Semin Dial. 2010;23(5):449–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eldehni MT, Odudu A, McIntyre CW. Randomized clinical trial of dialysate cooling and effects on brain white matter. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(4):957–965. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, Bhave N, Dietrich X, Ding Z, Eggers PW, Gaipov A, Gillen D, Gipson D, Gu H, Guro P, Haggerty D, Han Y, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Hsiung JT, Hutton D, Inoue A, Jacobsen SJ, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Kleine CE, Kovesdy CP, Krueter W, Kurtz V, Li Y, Liu S, Marroquin MV, McCullough K, Molnar MZ, Modi Z, Montez-Rath M, Moradi H, Morgenstern H, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O’Hare AM, Obi Y, Park C, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Potukuchi PK, Repeck K, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Schrager J, Selewski DT, Shamraj R, Shaw SF, Shi JM, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Sumida K, Kurella Tamura M, Tilea A, Turf M, Wang D, Weng W, Woodside KJ, Wyncott A, Xiang J, Xin X, Yin M, You AS, Zhang X, Zhou H, Shahinian V. US renal data system 2018 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3 Suppl 1):A7–A8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.2019 Researcher's guide to the USRDS database. Available online: https://usrds.org/research.aspx. Accessed 7 Jan 20. 2019.

- 7.Heung M. Outpatient Dialysis for acute kidney injury: Progress and pitfalls. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(4):523–528. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.03.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashani K, Rosner MH, Haase M, Lewington AJP, O'Donoghue DJ, Wilson FP, Nadim MK, Silver SA, Zarbock A, Ostermann M, Mehta RL, Kane-Gill SL, Ding X, Pickkers P, Bihorac A, Siew ED, Barreto EF, Macedo E, Kellum JA, Palevsky PM, Tolwani AJ, Ronco C, Juncos LA, Rewa OG, Bagshaw SM, Mottes TA, Koyner JL, Liu KD, Forni LG, Heung M, Wu VC. Quality improvement goals for acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):941–953. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01250119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker BM, Freedman BI. Need to reclassify etiologies of ESRD on the CMS 2728 medical evidence report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(3):477–479. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08310817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruzel-Davila E, Wasser WG, Aviram S, Skorecki K. APOL1 nephropathy: from gene to mechanisms of kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(3):349–358. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grams ME, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Estrella MM, Foster MC, Tin A, Kao WH, Coresh J. Explaining the racial difference in AKI incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(8):1834–1841. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laster M, Shen JI, Norris KC. Kidney disease among African Americans: a population perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(5 Suppl 1):S3–S7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor DM, Fraser S, Dudley C, Oniscu GC, Tomson C, Ravanan R, Roderick P. Investigators a: health literacy and patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(9):1545–1558. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronoff GR. The effect of treatment time, dialysis frequency, and ultrafiltration rate on intradialytic hypotension. Semin Dial. 2017;30(6):489–491. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Movilli E, Gaggia P, Zubani R, Camerini C, Vizzardi V, Parrinello G, Savoldi S, Fischer MS, Londrino F, Cancarini G. Association between high ultrafiltration rates and mortality in uraemic patients on regular haemodialysis. A 5-year prospective observational multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(12):3547–3552. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Levin NW, Twardowski ZJ, Wizemann V, Saito A, Kimata N, Gillespie BW, Combe C, Bommer J, Akiba T, Mapes DL, Young EW, Port FK. Longer treatment time and slower ultrafiltration in hemodialysis: associations with reduced mortality in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2006;69(7):1222–1228. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YJ, Okuda Y, Sy J, Lee YK, Obi Y, Cho S, Chen JLT, Jin A, Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E. Ultrafiltration rate, residual kidney function, and survival among patients treated with reduced-frequency hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):342–350. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pajewski R, Gipson P, Heung M. Predictors of post-hospitalization recovery of renal function among patients with acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2018;22(1):66–73. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) end-stage renal disease quality incentive program summary. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/ESRD-QIP-Summary-Payment-Years-2019-2024.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 20.

- 20.Heung M, Wolfgram DF, Kommareddi M, Hu Y, Song PX, Ojo AO. Fluid overload at initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with lack of renal recovery in patients with acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(3):956–961. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasgupta I, Thomas GN, Clarke J, Sitch A, Martin J, Bieber B, Hecking M, Karaboyas A, Pisoni R, Port F, Robinson B, Rayner H. Associations between hemodialysis facility practices to manage fluid volume and Intradialytic hypotension and patient outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(3):385–393. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08240718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), which is a publicly available data source. Requests for datasets can be made at https://usrds.org/for-researchers/.