Abstract

This review assesses the current state of knowledge about monetary sanctions, e.g., fines, fees, surcharges, restitution, and any other financial liability related to contact with systems of justice, which are used more widely than prison, jail, probation, or parole in the United States. The review describes the most important consequences of the punishment of monetary sanctions in the United States, which include a significant capacity for exacerbating economic inequality by race, prolonged contact and involvement with the criminal justice system, driver’s license suspension, voting restrictions, damaged credit, and incarceration. Given the lack of consistent laws and policies that govern monetary sanctions, jurisdictions vary greatly in their imposition, enforcement, and collection practices of fines, fees, court costs, and restitution. A review of federally collected data on monetary sanctions reveals that a lack of consistent and exhaustive measures of monetary sanctions presents a unique problem for tracking both the prevalence and amount of legal financial obligations (LFOs) over time. We conclude with promising directions for future research and policy on monetary sanctions.

Keywords: monetary sanctions, fines, legal financial obligations

INTRODUCTION

Monetary sanctions are the most common form of punishment imposed by criminal justice systems across the United States. Despite their ubiquity and routine imposition in response to offenses ranging from traffic violations to the most serious criminal offenses, monetary sanctions are understudied and undertheorized in criminology. Monetary sanctions fulfill multiple symbolic and practical functions within the criminal justice system, including retribution, deterrence, restoration, and revenue generation. As a result, monetary sanctions comprise a diverse set of penalties with varying purposes and justifications. For example, fines are imposed as punishment, but restitution is typically sentenced as a means to restore crime victims’ losses. Court fees and surcharges are added on to base fines to generate revenue to fund courts, other criminal justice operations, or even general government activities.

Monetary sanctions are often referred to as intermediate, alternative, or less-restrictive punishments (Gordon & Glaser 1991, Hillsman 1990, Morris & Tonry 1990, 42 Pa.C.S.A § 9721). Yet in current practice, monetary sanctions are very often sentenced in addition to other common penalties such as community service, probation or parole, and incarceration (Adamson 1983, Bannon et al. 2010, Blackmon 2009, Oshinsky 1997). For people with the means to pay, monetary sanctions may simply be an inconvenience, but for those with more limited means, criminal justice debt can become an onerous burden that triggers serious and escalating consequences (Harris 2016).

Given these diverse meanings, functions, and consequences, how can monetary sanctions be understood as a form of punishment in contemporary society? Studies to date are limited by the lack of nationally representative data covering the full range of monetary sanctions. As a result, what is known about the workings of monetary-sanction systems comes primarily from research conducted in single states (e.g., Harris 2016). Nevertheless, recent events such as those in Ferguson, Missouri, are increasingly bringing monetary sanctions to the forefront of policy makers’ attention. The US Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation of the Ferguson Police Department found that routine traffic stops frequently escalate into incarceration via the accumulation of unpaid monetary sanctions (US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015). Similar accounts are emerging from around the country (e.g., Back Road Calif. 2016, Wang 2015).

In this article, we review the current state of knowledge on monetary sanctions and propose directions for future research and policy. We focus on monetary sanctions in the United States, although the use of these sanctions, especially fines, is widespread internationally (Frase 2001; Kantorowicz-Reznichenko 2015; O’Malley 2009a,b).

CATEGORIES OF MONETARY SANCTIONS

Monetary sanctions take numerous forms, are codified by law, and are implemented at all levels of jurisdiction (city/municipal, county, state, and federal). They are assessed for all varieties of offense, from violations and summonses to misdemeanors and felonies. To lay the foundation for reviewing extant knowledge, we first introduce the various categories of monetary penalties.

Fines

Fines are financial punishments assessed by a judge upon conviction for any level of offense, typically specified in state statutes as a fixed dollar amount or variable range. Fines have a very long history in criminal sentencing, dating back to Biblical times (see Sichel 1982). The Anglo-Saxons had a system of fines (Pollock & Maitland 1895), and the perceived injustice of undue fines was an impetus for the Magna Carta (Zitzer 1988, 1989). In the United States, fines have often been used to reinforce systems of racial stratification. As Harris et al. (2010, p. 1,758) explain: “[M]onetary sanctions were integral to systems of criminal justice, debt bondage, and racial domination in the American South for decades.” Apart from mandatory fines specified by statute, judges wield considerable discretion in deciding whether to fine and in setting the amount of a fine. Fines in the United States are typically assessed in addition to incarceration or supervision rather than as a replacement for such punishments, as is more common in other nations (O’Malley 2009a,b; 2011).

Restitution

Unlike fines, restitution can be a means to pursue restorative aims and accountability to crime victims. Restitution is generally intended to compensate victims for damage to property, medical expenses, or other offense-related costs. Restitution comes in two forms: direct restitution, which is paid to the victim for some quantifiable harm, and indirect restitution, which is paid to the state for disbursement to victims who apply for compensation. Judges often have wide latitude in sentencing direct restitution, whereas indirect restitution often takes the form of a mandatory surcharge for all manner of offenses as dictated by state statutes.

Court Fees

State laws also allow courts to charge criminal defendants fees to ostensibly recoup justice system costs. These fees vary greatly across jurisdictions. Judges have wide latitude in imposing some fees but others are statutorily mandated. Fees may include charges for the use of a public defender, the prosecutor’s time, or the cost of summoning expert witnesses. People can be charged for requesting a jury trial, for the execution of an arrest warrant by a sheriff, for monthly payment processing charges, or daily charges for incarceration. Fee amounts are generally specified as fixed amounts or ranges by statute and rarely have a connection to identifiable case-processing costs. Jurisdictions often exercise a great deal of discretion in how they design and implement fee policies. Currently, clear federal guidelines are lacking and state guidelines provide only loose parameters for guidance.

Surcharges and Assessments

Jurisdictions may levy surcharges and assessments on top of base fines, fees, and costs. These surcharges are flat or proportional charges and can also be added to monetary sanctions for every level of offense. Like fees, surcharges are commonly used to financially support courts and other government agencies. However, unlike fees, surcharges are imposed regardless of the actual criminal justice services used. Table 1 displays cross-state variation in the imposition of surcharges and assessments for a similar traffic offense. Surcharges and assessments for driving on a suspended license vary considerably by state and can be as high as $2,500 (e.g., in California).

Table 1.

Legal financial obligations and time to full payment for driving with a suspended license (Harris et al. 2016)

| State | Fine | Fees | Surcharges | Added charges |

Amount due at sentencing |

Total paid, $50 monthly, on-time payments |

Months until paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | $300–$1,000 | $4, incarceration costs | $60–200 | 12% interest, $946–$2,276 | $1,310–$3,480 | $1,310–$5,983 | 31–120 |

| Georgia | $500–$1,000 | $0 | $405–$805 | NA | $905–$1,805 | $905–$1,805 | 19–37 |

| Illinois | $0–$2,500 | $310, incarceration costs | $85–$1,022.50 | NA | $395–$3,832.50 | $395–$3,832.50 | 8–77 |

| Minnesota | $200 | $3–$13 | $75 | $0 | $279.50–$289.50 | $279.50–$289.50 | 6 |

| Missouri | $150–$500 | $12, incarceration costs | $19.50–$44.50 | $25 | $206.50–$582.50 | $206.50–$582.50 | 5–12 |

| North Carolina | $0-$200 | $125.50 | $35.50 | 4% interest | $188–$388 | $214.52–$431.31 | 5–9 |

| New York | $200–$500 | $50 | $83 | NA | $333–633 | $333–$633 | 7–13 |

| Texas | $0–$500 | $62.10 | $0–$300 | $25 | $62.10–$862.10 | $87.10–$887.10 | 2–18 |

| Washington | $0–$1,000 | $200 | $250 | 12% interest, $100 annual | $450–$1,450 | $686.85–$2,222.88 | 14–45 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

IMPACTS OF MONETARY SANCTIONS

Monetary sanctions have several defining characteristics. Monetary sanctions affect a person’s ability to reintegrate into society post-incarceration and, in some states, can accrue indefinitely. Yet the person who receives the sanction does not necessarily have to be the person who pays it. As a result of these features, the impacts of monetary sanctions are extensive and substantial. The proceeding section reviews several of the most important effects of the current system of monetary sanctions in the United States, noting the limitations of data availability where applicable.

Social Stratification

Despite the lack of robust quantitative data to examine the effect of monetary sanctions on social stratification, a variety of factors strongly suggest their capacity for exacerbating economic and racial inequality. For instance, for every $1 a typical African-American family owns, a typical Caucasian family owns $15.63, and for every $1 a typical Latino family owns, a typical Caucasian family owns $13.33 (Sullivan et al. 2015). American criminal justice is also characterized by deep racial and ethnic inequality. The nationwide arrest rate for African Americans is 2.5 times that for Caucasians (Hartney & Vuong 2009). After arrest, the odds of being released after paying bail are twice as high for incarcerated Caucasians compared to Latinos and African Americans (Schlesinger 2005). There is also abundant evidence that race has a significant effect on sentencing outcomes (Green 1961, Kleck 1981, Mitchell 2005, Spohn 2000).

Western (2006), for example, shows that African-American and Latino men with low educational achievement, high unemployment, and low wages are more likely than equivalent Caucasian men to be ensnared in the criminal justice system. Overwhelmingly, felony defendants come from poverty-stricken neighborhoods and under- and unemployed contexts (Pager & Western 2009) and have failed in their school systems (Bersani & Chapple 2007, Kalleberg 2011, Peterson & Krivo 2010). Given that monetary sanctions are usually imposed in addition to, rather than in lieu of, incarceration and other forms of punishment, it is likely that their effects are most pronounced among those who are already economically, socially, and politically disadvantaged. Taken together, the vast racial disparities in wealth combined with the significant racial disparities throughout the criminal justice system and the monetary sanctions that accrue at each step of case processing create enormous potential for these sanctions to worsen racial disparities.

Indeed, state-level analyses of monetary-sanction statutes show that the majority of felony defendants have had legal debt imposed at sentencing (Harris 2016, Harris et al. 2010). Monetary sanctions are also imposed for a wide range of misdemeanor and traffic offenses, which significantly broadens their scope. Even relatively small fines assessed for minor offenses can trigger the accumulation of fees, costs, and surcharges (Harris et al. 2016). Thus, monetary sanctions both intensify the punishment of people with felony convictions by adding on to other punishments, e.g., incarceration, and widen the reach of the criminal justice system into the lives of people who would otherwise be unaffected but for their minor infraction citations like traffic or other low-level offenses.

Collateral Consequences

People with outstanding monetary-sanction debt often experience numerous additional penalties that interfere with economic and social well-being, even for non-felony offenses. The baseline collateral consequence is simply prolonged contact and involvement with the criminal justice system. People are subject to the regular court summons, the issuance of warrants, and pursuit by private collection agencies. The repercussions of criminal justice debt ultimately touch on many aspects of life.

One of the most detrimental consequences of unpaid monetary sanctions is driver’s license suspension. The practice is not only widespread but, insofar as it constrains employment and childcare options, directly undermines the goal of people successfully separating from the criminal justice system. A study of legal statutes in nine states reveals that all nine states allow for driver’s licenses to be suspended for unpaid monetary sanctions in at least some cases. State laws in California, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Texas allow for the suspension of driver’s licenses for any unpaid legal financial obligations (LFOs). In the remaining five states (Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, New York, and Washington), driver’s licenses can be suspended only for unpaid monetary sanctions related to vehicle or traffic violations (Harris et al. 2016). Moreover, evidence in California suggests that this practice entails significant racial disparities. For example, in the City and County of San Francisco, African Americans are 5.8% of the population but are 48.7% of the arrestees for “failure to appear/pay” traffic court warrants (Back Road Calif. 2016). In contrast, Caucasians are 41.2% of the population but only 22.7% of those arrested for driving with a suspended license (Back Road Calif. 2016). This amounts to African Americans being overrepresented by a factor of 8.4, whereas Caucasian residents are underrepresented by a factor of 0.6 (Back Road Calif. 2016).

Unpaid criminal justice debt can also lead to a loss of voting rights. Thirty states disenfranchise people either fully or conditionally (e.g., upon missing a payment) for debt related to a felony conviction, and eight states do so for misdemeanor convictions (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, and South Carolina) (Fredericksen & Lassiter 2016). Nine states (Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, and Tennessee) explicitly list unpaid monetary sanctions in their disenfranchisement laws (Fredericksen & Lassiter 2016).

A consequence of potentially enormous impact is the practice of reporting unpaid criminal justice debt to credit agencies. This can compromise good credit scores needed to secure housing, automobiles, employment, and credit itself (e.g., credit cards, mortgages, loans). The reporting of criminal justice debt to credit bureaus can happen as a result of civil judgments (e.g., New York), which are publicly available information, or because jurisdictions have a policy of directly reporting all debt (e.g., Nevada). Moreover, unpaid monetary sanctions can prompt liens, wage garnishment, and tax rebate interception (Bannon et al. 2010). In this way, monetary sanctions have the distinct ability to transgress the traditional boundary between civil and criminal law.

Perhaps the most troubling consequence of unpaid monetary sanctions is incarceration. Failure to pay monetary sanctions, including restitution, can be grounds for the revocation of parole or probation, which triggers incarceration. Parole and probation revocation happen as people are incarcerated not necessarily for new offenses but because not paying monetary sanctions often violates sentencing conditions. People do not even need to be on probation to become incarcerated for nonpayment. Some counties issue a court summons when someone misses payment and issue arrest warrants upon failure to appear in court. [Note that a warrant alone can lead to collateral consequences, such as the loss of federal or state welfare benefits or job loss, in addition to triggering incarceration for nonpayment and failure to appear (Harris 2016)]. In fact, the practice of incarcerating people for nonpayment has recently garnered a great deal of public attention over concerns about debtors’ prisons. Evidence from around the country reveals that debtors’ prisons do in fact exist, and advocacy groups have mounted legal challenges on the premise that incarceration is an acceptable consequence of unpaid monetary sanctions (Am. Civ. Lib. Union 2010; 2015a,b; Am. Civ. Lib. Union Wash. Columbia Leg. Serv. 2014; Am. Civ. Lib. Union La. 2015; Bannon et al. 2010; Hager 2015; Regnier 2015; Shapiro 2014; South. Cent. Hum. Rights 2013).

People are routinely incarcerated for failure to pay monetary sanctions, despite the Supreme Court ruling in Bearden v. Georgia (1983) that prohibits courts from doing so unless they find that a person “willfully” fails to pay. The language of court decisions, including Bearden, stipulates that if “reasonable,” “sufficient bona fide,” or “good faith” efforts to pay have been made, people cannot be held in contempt for nonpayment. In practice, judges have interpreted these legal concepts as requiring defendants, even those who are indigent and homeless, to go to great lengths to secure the means for payment, including seeking loans from friends, family members, and employers, or taking day-laborer jobs (Harris 2016). In addition, some localities have institutionalized auto-jail, pay-or-stay or pay-and-sit, or sitting-out fines policies. The latter two policies entail sentencing people to a set number of days in jail in exchange for a certain amount of financial credit toward their debt (Harris 2016).

Law Enforcement

Deficits at every level of government put pressure on public institutions to cut costs or to produce revenue, prompting the Government Accountability Office to predict that state and local governments will “continue to face a gap between revenue and spending during the next 50 years” (Gov. Account. Office 2015, p. 1). The ensuing predicament is that, as a consequence, public institutions become both the originator and the beneficiary of monetary sanctions (Beckett & Harris 2011, Reynolds & Hall 2011, US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015). To wit, payments for monetary sanctions do, in fact, generate revenue. For example, the California Legislature has been diverting money from the State Penalty Fund (the destination of fine and fee payments) to the General Fund for decades (Nieto 2006). Other jurisdictions, such as the court system in Nevada and probation departments in Texas, similarly rely on revenue from monetary sanctions (McLean & Thompson 2007). In the New York metropolitan area, fines generate 47% of criminal court revenue, which is split between New York City and New York State (each receives approximately $14,000,000).

The problem is that the pursuit of revenue makes debt collectors out of law enforcement officers, and police contact is the dominant entry point to the criminal justice system (Bur. Justice Stat. 1997). The role of monetary sanctions in increasing the likelihood of interaction with law enforcement can take various forms. Police may inordinately act on warrants for nonpayment (which revokes parole or probation) or they may disproportionately pursue infractions that carry fines. Current policy creates these potentialities (e.g., Office City Audit. 2011, US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015) and anecdotal evidence shows that they occur (e.g., Hitt 2015, Simmons 2014). It is increasingly clear that criminal justice debt may be both a cause and effect of police contact (e.g., US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015), which can undermine community policing efforts, detract from non-revenue-producing law enforcement, and generally disrupt the purposes of policing.

Evidence from jurisdictions around the country demonstrates how law enforcement participates in imposing and collecting monetary sanctions. Data from Hillsborough County, Florida, show that revenue from civil traffic fines dwarfs that of other types of courts (e.g., criminal, juvenile, and non-traffic civil) (Blakke 2009). It is problematic when jurisdictions and agencies become dependent on revenue from monetary sanctions. For instance, the Nevada Supreme Court recently went broke because revenue from traffic tickets plummeted (Knowles 2015), and the city of San Jose, California, lamented the drop in traffic violation revenue (Office City Audit. 2011).

The systemic pressure on law enforcement to assist with collecting criminal justice debt produces untenable situations like the warrant redemption program in Texas (Maass 2016, Mawajdeh 2016, Weiss 2016). The state legislature passed a bill in 2015 (H.B. 121) that allows for credit card readers to be installed in police patrol vehicles. At the same time, some counties have contracts for automatic license plate reading (ALPR) technology. The counties give all of their outstanding court fee data to the ALPR company, which then collects a 25% surcharge on the debt. Technically, people who are stopped under this program are given a choice of arrest or immediate payment. They can either pay the amount they owe plus a $125 processing fee or they can be arrested, go to jail, have their car towed and impounded, and miss work or any other obligations they may have. Clearly, this choice is a false one to people who cannot afford to pay the debt on the spot. Not only does this program create individual dilemmas, but it also creates an incentive to focus on revenue-producing warrants rather than traffic violations in real time. Moreover, it is a law enforcement model based on debt, with no incentive to reduce the number of warrants, which would put at risk both the free ALPR equipment and the revenue it helps produce.

Recidivism

There is good reason to suspect that monetary sanctions might affect recidivism, although very few studies explore these effects. On the positive side, there is some evidence to suggest that monetary sanctions directed primarily at restitution contribute to lower recidivism rates (Gordon & Glaser 1991, Ruback et al. 2004). On the negative side, to the extent that people are unable to pay the monetary sanctions imposed, recidivism might be expected to increase. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that monetary sanctions increase the likelihood of probation revocation among adults (Gordon & Glaser 1991). In a study of a sample of juveniles in Pennsylvania, owing restitution and other costs significantly increased the likelihood of subsequent adjudication and conviction (Piquero & Jennings 2016). Overall, given the extent of the other collateral consequences of monetary sanctions, there is reason to expect a non-negligible criminogenic effect of unpaid criminal justice debt.

SOURCES OF VARIATION IN THE IMPOSITION OF MONETARY SANCTIONS

Although the use of monetary sanctions is widespread in the United States, jurisdictions vary a great deal in their systems of monetary sanctions (Harris et al. 2016). There is no nationally consistent set of laws, policies, or principles that govern monetary sanctions.

At the individual level, demographic characteristics like race, ethnicity, gender, and age are associated with type and severity of monetary sanctions imposed. In Washington State, for example, net of legal factors Latinos receive higher monetary sanctions than non-Latinos (Harris et al. 2011). In other states, such as Pennsylvania, race and ethnicity appear to have no association with the total amount of monetary sanctions but type of offense is most pertinent (Ruback & Clark 2011, Ruback et al. 2004). Across several states, fines and fees are more likely to be imposed for drug and traffic offenses, whereas restitution is more likely to be assessed for property crimes (Gordon & Glaser 1991, Harris et al. 2011, Ruback & Clark 2011, Ruback et al. 2004). Other characteristics also predict the imposition of monetary sanctions for both misdemeanor and felony offenses (Gordon & Glaser 1991, Harris et al. 2011, Ruback & Clark 2011). Men are more likely to have higher monetary sanctions assessed in Washington State (Harris et al. 2011). Age has a negative effect on the dollar amount of monetary sanctions imposed in Pennsylvania, with youth being less likely to receive higher sanctions (Ruback & Clark 2011).

County-level analyses within individual states have shown few consistent predictors of the amount of monetary sanctions imposed. In Washington State, for example, the percent of a county’s population that vote Republican increases the amount of fines and fees assessed (Harris et al. 2011). But in Pennsylvania, no county-level factors are significantly associated with monetary sanction amounts net of individual case factors (Ruback & Clark 2011). At the federal level, offense type is a strong predictor of the likelihood of receiving a monetary sanction, with up to 96% of some offense categories receiving one (US Sentencing Comm. 2015).

The Promises and Pitfalls of Publicly Available Data on Monetary Sanctions

Although robust nationwide data are thus far nonexistent, we can use two types of secondary data to examine a subset of monetary sanctions in America: sample surveys and automated court records. Our review of existing data sources shows that both types of data lack extensive information on all forms of monetary sanctions and that even when data are collected on specific types of monetary sanctions, the amount imposed is rarely asked, particularly in survey data. The lack of consistent and exhaustive measures of monetary sanctions presents a unique problem for tracking both the prevalence and amount of LFOs over time.

Table 2 lists survey items that measure monetary sanctions in national and state data (US Dep. Justice 1972; 1978; 1979; 1983; 1986; 1989; 1991a,b; 1996; 1997; 2002; 2004). Since the early 1970s, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has routinely administered sample surveys to the inmate population. The Surveys of Inmates in Local Jails and the Surveys of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities have inquired about the imposition of specific types of monetary sanctions over time. However, the types of monetary sanctions vary considerably by survey and period. For example, defendants may be charged for legal representation by public defenders if judges determine that defendants have sufficient means to pay for the cost of their defense. In 1972, the Survey of Jail Inmates asked if inmates had a private attorney or public defender and whether the family was required to pay for the legal services. A similar question was asked in the 1978 Survey of Jail Inmates; yet, by 1983, this question was no longer asked of jail inmates. Similarly, in 1979, the only monetary sanction question raised in the Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities was if the inmate was ordered to pay restitution. This question was asked again in the 1986 survey, but the 1991 survey extended the list of possible monetary sanctions to include information on fines, court costs, and a host of court-ordered substance abuse testing and treatment programs. The inaugural Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities also included this list of possible monetary sanctions in 1991. Since 1997, the Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities has continued to ask and itemize a host of questions on monetary sanctions that include fines, court costs, restitution, and court-ordered programs. The 1996 Survey of Inmates in Local Jails adopted a similar set of survey items, allowing for greater comparability with state and federal data on monetary sanctions.

Table 2.

The prevalence of survey items on monetary sanctions in national and state data

| Year | Data source | Question | Answer type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Survey of Jail Inmates | Do you or did you have a lawyer or public defender and if so, did you or your family have to pay for the lawyer’s services? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1978 | Survey of Jail Inmates | Did you have to pay for legal counsel? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1979 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities | What type of disciplinary action taken: restitution? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1983 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Are you in jail today because you could not afford to pay a fine imposed by the court? (does not include bail or restitution) | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1986 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities | What type of disciplinary action taken: fee/restitution? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1988 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Did your sentence include any special conditions or restrictions, that is anything other than jail time, prison time, parole, or probation, like restitution to the victim? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Does your sentence include any special conditions or restrictions, such as fines, court costs, restitution, community service, drug testing or treatment, or any other conditions? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include a fine? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include restitution? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include court costs? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include community service? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug testing? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include alcohol treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include sex offender treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include psychiatric or psychological counseling? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

Do these special conditions or restrictions include any other special conditions or restrictions? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1991 | Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities Survey of Inmates of Federal Correctional Facilities |

What were the specific reasons that your parole/other conditional release was revoked: failure to pay fines, restitution, or other financial obligations (e.g., child support)? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Does your sentence include a fine? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Does your sentence include court costs? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Does your sentence include restitution to the victim? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Does your sentence include other types of fees or monetary sanctions? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | If yes, how much was the total dollar amount? | Continuous |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include community service? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug testing? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug or alcohol treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include sex offender treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include psychiatric or psychological counseling? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1996, 2002 | Survey of Inmates in Local Jails | Do these special conditions or restrictions include any other special conditions or restrictions? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | What were the specific reasons that your parole or supervised release was taken away or revoked: failure to pay fines, restitution, or other financial obligations (e.g., child support)? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Did your sentence include court costs? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Did your sentence include a fine? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Did your sentence include restitution to the victim? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Did your sentence include another type of fee or monetary sanction? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include community service? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug testing? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include mandatory drug or alcohol treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include sex offender treatment program? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include psychiatric or psychological counseling? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1997, 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities | Do these special conditions or restrictions include any other special conditions or restrictions? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1988–1989, 1990–1991 |

National Pretrial Reporting Program | Sentence received: fine? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1988–1989, 1990–1991, 1992–1993 |

National Pretrial Reporting Program | Fine amount? | Continuous |

| 1990–1991 | National Pretrial Reporting Program | Combined sentenced received: fine? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–1991 | National Pretrial Reporting Program | Combined sentenced received: restitution? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–1991, 1992–1993 |

National Pretrial Reporting Program | Sentence received: restitution? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–1991, 1992–1993 |

National Pretrial Reporting Program | Restitution amount? | Continuous |

| 1992–1993 | National Pretrial Reporting Program | Sentence received: fine, restitution, and/or community service? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–2009 | State Court Processing Statistics | Fine imposed? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–2009 | State Court Processing Statistics | Fine amount? | Continuous |

| 1990–2009 | State Court Processing Statistics | Restitution required? | Binary (Y/N) |

| 1990–2009 | State Court Processing Statistics | Restitution amount? | Continuous |

| 2006–2015 | Annual Parole Survey | On December 31, how many adult parolees supervised by your agency had a status of only having financial conditions remaining? | Continuous |

Although the Surveys of Inmates contain binary questions about whether or not fines, court costs, restitution, and court-ordered programs are imposed, the dollar amounts of these LFOs are rarely collected. The 1996 Survey of Inmates in Local Jails is the only questionnaire that assesses the total dollar amount of other types of fees and monetary sanctions, such as supervision costs and mandatory assessments. However, the amount of fines, court costs, restitution orders, and special programs are never asked in any of these surveys.

The lack of detailed information about the total fines, fees, and/or restitution imposed at sentencing is offset by gains in how these financial penalties are related to future entanglements with the criminal justice system. Since 1991, state and federal inmates were regularly asked if their probation or parole was revoked for failure to pay these monetary sanctions. The Survey of Inmates in Local Jails began asking about parole and probation revocation due to monetary sanctions in 2002. In 1994, the Bureau of Justice Statistics began fielding the Annual Parole Survey, which collects administrative data on probation and parole in all 50 states, the federal system, and the District of Columbia. By 2006, the Annual Parole Survey began collecting data on the number of parolees who have only financial conditions remaining as a part of their sentence (US Dep. Justice 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014a, 2015). These data, when combined with the Survey of Inmates, would have allowed for national and state estimates of the likelihood of reincarceration as a result of failure to pay monetary sanctions. However, because the Annual Parole Survey did not inquire about the unpaid financial obligations among parolees until after the 2004 Survey of Inmates, population-level estimates of the risk of parole revocation due to LFOs is more difficult to quantify.

Another source of secondary data on monetary sanctions is automated court records. In the early 1980s, the Bureau of Justice Statistics wanted to determine the feasibility of a national pretrial database. Before 1988, there was no national system for collecting information on individual and case characteristics until adjudication and sentencing. The 1988–1993 National Pretrial Reporting Program (NPRP) provides a detailed picture of felony defendants moving through criminal courts in 40 of the 75 most populous counties (Pretr. Serv. Resour. Cent. 2011a,b; 2013). The first iteration of the data only contained information on whether a fine was imposed and the amount of the fine. Subsequent waves of data included individual measures of whether fines and restitution were imposed as well as the amounts of the fines and restitution orders.

By the mid-1990s, the NPRP was replaced by State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS). The SCPS, like the NPRP, tracks felony cases in approximately 40 of the 75 most populous counties and collected this information biennially from 1990 through 2006 and again in 2009 (US Dep. Justice 2014b). These 75 counties make up more than a third of the US population and approximately half of all reported crimes. The SCPS samples court cases filed in May of a given year and tracks the life cycle of the case until final disposition or until one year has passed from the filing date. These data contain information on whether fines and restitution were imposed and the amounts of each monetary sanction. Court costs, surcharges (mandatory or otherwise), collection fees, public defender charges, special assessment fees, and costs for court-ordered programs (drug monitoring, domestic violence rehabilitation, and driving lessons) are not contained in the data. Given that the number of court-ordered programs and the cost of participation have increased significantly since the 1990s, these forms of financial obligations represent a critical omission in automated court data on monetary sanctions.

Findings from the State Court Processing Statistics

Robust nationwide data on the use of monetary sanctions are thus far nonexistent. To illustrate the limitations of existing data sources on monetary sanctions, we explore what the SCPS can tell us about the frequency with which courts sentence fines for felonies and the amount of fines they tend to sentence across jurisdictions and over time. We construct descriptive statistics and trends on the imposition of fines and restitution in these data. All estimates are weighted, and monetary values are expressed in 2016 dollars.

Table 3 lists the counties sampled in the SCPS, along with the coverage of the SCPS data across counties over time. Despite the relatively large number of counties included in the SCPS, only 12 counties are included in every wave of the data; either 39 or 40 counties are sampled for each wave of data. More than half of the counties listed below are missing in at least 50% of SCPS waves. Although the data provide valuable insight into individual-level case processing, their utility for comparative and time-series analysis may be restricted to the handful of counties sampled in each wave of the survey.

Table 3.

County coverage in the state court processing statistics (SCPS), 1990–2009

| County | Percent of waves includeda |

|---|---|

| Maricopa, AZ; Los Angeles, CA; San Bernardino, CA; Broward, FL; Dade, FL; Cook, IL; Wayne, MI; Bronx, NY; Kings, NY; Shelby, TN; Dallas, TX; Harris, TX | 100 |

| Pima, AZ; Orange, CA; Santa Clara, CA; Honolulu, HI; Essex, NJ; Philadelphia, PA | 80 |

| Hillsborough, FL; Marion, IN; Montgomery, MD; St Louis, MO; New York, NY; Hamilton, OH; Tarrant, TX; Salt Lake, UT; King, WA | 70 |

| Jefferson, AL; Alameda, CA; Fulton, GA; Queens, NY; Fairfax, VA; Milwaukee, WI | 60 |

| Sacramento, CA; San Diego, CA; Ventura, CA; Orange, FL; Palm Beach, FL; Pinellas, FL; Baltimore (County), MD; Erie, NY; Monroe, NY; Suffolk, NY; Franklin, OH; Allegheny, PA; El Paso, TX | 50 |

| San Francisco, CA; Nassau, NY; Montgomery, PA | 40 |

| Contra Costa, CA; Riverside, CA; San Mateo, CA; DuPage, IL; Jefferson, KY; Baltimore (City), MD; Jackson, MO; Westchester, NY; Travis, TX | 30 |

| Hartford, CT; Washington, DC; Duval, FL; Essex, MA; Suffolk, MA; Prince George, MD; Macomb, MI; Oakland, MI; Wake, NC; Middlesex, NJ; Cuyahoga, OH | 20 |

| New Haven, CT; Middlesex, MA | 10 |

Authors’ calculations of the SCPS.

Table 4 details the characteristics of cases described in the SCPS data for those counties that are included in all waves, including total caseloads represented in the data, the percent of violent or property and drug felony defendants sentenced to pay fines, and the median fine amount for defendants convicted of either violent felonies or property and drug felonies sentenced to pay fines. Across all waves of the data, and inclusive of all sample counties, approximately 20% of defendants initially charged with a felony and ultimately convicted of either a misdemeanor or a felony were sentenced to pay fines. The median amount for those sentenced to pay fines was $506, in 2016 dollars. Approximately 12% of all convicted defendants in the SCPS were sentenced to pay restitution, with a median sentenced amount of $400. There is, however, substantial variation in the sentencing of fines across jurisdictions.

Table 4.

Sentenced fines and restitution among counties included in all waves of the state court processing statistics (SCPS), 1990–2009a

| County | Percent of convictions with fine |

Percent of convictions with restitution |

Median fine ($) | Median restitution ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maricopa, AZ | 40 | 18 | 1,551 | 1,580 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 9 | 17 | 308 | 294 |

| San Bernardino, CA | 10 | 25 | 306 | 679 |

| Broward, FL | 16 | 5 | 417 | 1,065 |

| Dade, FL | 24 | 3 | 388 | 1,455 |

| Cook, IL | 7 | 2 | 680 | 484 |

| Wayne, MI | 7 | 29 | 548 | 76 |

| Bronx, NYb | 7 | 0 | 320 | NA |

| Kings, NY | 10 | 0 | 323 | 171 |

| Shelby, TN | 72 | 1 | 769 | 603 |

| Dallas, TX | 72 | 14 | 862 | 1,208 |

| Harris, TX | 11 | 1 | 862 | 1,846 |

| Full SCPS, all waves | 20 | 12 | 506 | 400 |

| National difference between SCPS 2009 wave and 1990 wave | 3 | 3 | 38 | 10 |

Authors’ calculations of the SCPS.

The median restitution for Bronx, NY, is unobservable because no cases included in the SCPS reported a restitution sentence. Fines and restitution are expressed in 2016 dollars.

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Counties vary dramatically in the frequency with which they impose fines. Dallas County, Texas, and Shelby County, Tennessee, imposed fines most frequently among those counties fully covered in the SCPS data, whereas Wayne County, Michigan, and Bronx and King Counties in New York imposed fines relatively infrequently. The median sentenced fines in Maricopa County, Arizona, were substantially higher than the median sentenced fines in any of the other counties fully covered in the data. Counties also vary substantially in their use of restitution. Although Wayne County, Michigan, sentenced convicted defendants to pay restitution in 29% of all cases, defendants in many counties were rarely or never sentenced to restitution. And although defendants in Wayne County were often sentenced to restitution, the sentenced amount was usually very low, in contrast to Maricopa County, Arizona, which sentenced restitution less frequently but for far higher amounts. This cross-sectional variation suggests that the jurisdiction of sentencing plays an important role in the amount of legal debt a convicted criminal defendant will owe. It is important to note that these figures are conservative estimates of both the frequency of cases in which courts impose financial penalties and the total amount of debt imposed because these data exclude surcharges, court and legal system fees, interest, and other costs borne by defendants.

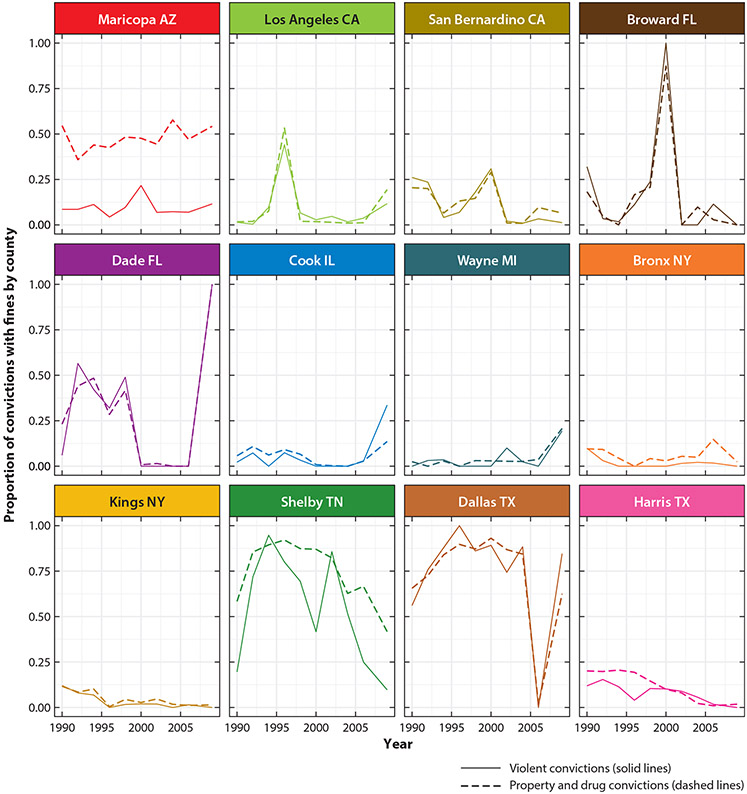

Altogether, the SCPS provides little evidence of a clear national trend in the sentencing of fines for felonies in the included counties. Figure 1 shows the proportion of defendants convicted of violent, property, and drug offenses sentenced to pay fines by county at each wave of data collection between 1990 and 2009. Although some counties experienced dramatic wave-to-wave fluctuations, such as Broward and Dade Counties in Florida, Shelby County, Tennessee, and Dallas County, Texas, most counties remained relatively stable in the rate at which they sentenced fines to those initially charged with a felony and ultimately convicted of either a misdemeanor or a felony. The SCPS indicates that the proportion of defendants in large counties sentenced to pay fines actually decreased by 3% between 1990 and 2009, whereas the proportion of defendants sentenced to pay restitution increased by 3%. The median sentenced fine increased by $38 between 1990 and 2009 (inflation adjusted), and the median sentenced restitution increased by $10. Notably, several county observations record no sentenced fines, which may be a sampling artifact. On their own, these time-series data provide little evidence of a uniform positive trend in increasing rates of sentencing fines.

Figure 1.

The proportion of convictions with sentenced fines among counties in all waves of the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS), 1990–2009. Violent convictions are the solid line; property and drug convictions are the dashed line. Source: authors’ calculations of the State Court Processing Statistics.

Limitations of the State Court Processing Statistics Database

As the only national data system that details sentencing outcomes across many jurisdictions, the SCPS provide our best source for comparative statistics on felony sentencing outcomes. Yet there are several reasons to be concerned about using the SCPS data to describe county trends in the imposition of monetary sanctions. First, the design of the SCPS restricts sampling to only courts in the 75 most populous counties. The sentencing of monetary sanctions in rural counties may exhibit distinctly different characteristics when compared with sentencing from the urban counties described in the SCPS.

Second, the SCPS data only sample cases within a one-month period (May) for each biennial year. It could be that May is not a representative case filing month for a calendar year or biennium period. Because the SCPS does not weight-up the data to either the calendar year or biennial period, it is unknown whether estimates are representative of all cases every two years, even if they are representative of the month of May. Moreover, there is an assumption that the underlying distribution of case characteristics is uniform across calendar months and biennium, which may not be observed in these time-series comparisons.

Third, there is reason to believe that some sampling weights have been calculated incorrectly. The SCPS employs a two-stage sampling process; in the first stage, they select counties. There are four strata in the first stage of selection, and ten counties are taken with certainty in Stratum 1 because of the volume of their felony filings, whereas counties in other strata were not taken with certainty. Because there was an error made for one of the counties to be taken with certainty, this county was removed, thereby changing the sampling weight for Stratum 1 from 1.0 to 1.11. Strata 2, 3, and 4 were then constructed based on the variance of court filings, population, and arrest data. Stratum 2 counties had fewer filings than Stratum 1 counties but more than Stratum 3 counties, and Stratum 4 counties had the lowest number of filings. Counties were ordered within strata by census region and court filings. The codebook states that the weights associated with Strata 1–4 are 1.111, 1.714, 2.0, and 2.5, respectively. However, an examination of the county weights in the data reveals that there are 14 different county weights for the period, ranging from 1.0 to 3.889.

Finally, these data exclude cases not initially charged with a felony. The SCPS cannot provide any information on changes in the frequency of sentencing or the amount of fines sentenced for misdemeanor and traffic charges over time. Similarly, these data do not capture monetary sanctions that are not formally part of a sentenced defendant’s punishment, such as fees, surcharges, assessments, interest, and court-ordered programs. These omitted sanctions often make up a substantial portion of the total debt incurred by those who encounter the criminal justice system, although existing data systems limit our ability to learn about their use across jurisdictions and over time. Nevertheless, the SCPS database is the only federal data system that details fine and restitution amounts across multiple jurisdictions. As such, the SCPS provide our most reliable source for comparative statistics on felony sentencing outcomes but have substantial limitations for the study of monetary sanctions more broadly.

CHANGES IN MONETARY-SANCTION POLICY AND LAW

Understanding the policy implications of monetary sanctions in the United States starts with acknowledging the meager empirical basis on which to develop policy. Policy, as a discipline, holds empirics at the core of its praxis. Despite some important exceptions (Harris 2016; Harris et al. 2010, 2011, 2016), the empirics on which to base policy formulation in this domain are inadequate. As outlined at the outset, the bulk of extant literature is limited to a single jurisdiction, is dated, or is atheoretical. The subsequent section summarizes bona fide changes in law, pivotal legal challenges, and important changes in policy.

Missouri has been the site of some of the most problematic manifestations of monetary sanctions and, as a result, some of the most promising reform in the form of statutory change. The 2014 killing of the unarmed African-American teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer, along with a report on fines and fees written by a public defender agency (Harvey et al. 2014), prompted a DOJ investigation of Ferguson’s police department, as mentioned above. In the course of identifying systemic issues of racial bias, the DOJ found that the municipality had an extortionate system of monetary sanctions. Essentially, city leaders were treating residents and passers-through as a source of government revenue. In fact, the report details how the City Finance Director wrote to both the Police Chief1 and the City Manager2 explicitly urging increased ticket writing for the sake of city income.

The revelation of just how profoundly unscrupulous fining practices were, coupled with the tenacious efforts of local legal advocates, prompted a notable set of policy reforms. First, the courts issued an order (Rule 37.65, 2014) that allows for people deemed to “not have at that time the present means to pay the fine” to pay fines in installments. It also allows for judges to reduce or waive unpaid fines. The following year, the legislature passed Senate Bill 5, which capped the annual general operating revenue that can come from traffic fines. Now, these fines can only constitute 20%3 (reduced from 30%) of a city’s general operating revenue.4 Cities can no longer add charges for “failure to appear” when a person misses a court date nor can they assess more than $300 for minor traffic offenses. Perhaps most importantly, given the region’s egregious abuse of a policy of incarcerating people for nonpayment, the bill also prohibits jail time for minor traffic offenses.

The courts in Biloxi, Mississippi, which also previously incarcerated indigent people for failure to pay court-ordered fines, exemplify policy change via legal challenge. Here, instead of legislative action, the courts changed their policy as a result of settling a federal lawsuit filed by the ACLU. The changes included prohibiting private probation companies from collecting fines and fees, hiring a public defender to represent indigent people charged with nonpayment, and not adding fees to the debt owed by people paying on installment plans or sentenced to community service.

A key outcome of the settlement was the development of a “bench card” for all Biloxi municipal judges. This is a laminated sheet of paper with guidelines about right to counsel and imposition and collection of monetary sanctions. It recommends that, when imposing monetary sanctions, judges consider whether the person is homeless, incarcerated, or has an annual income at or below 125% of the federal poverty level. It also proscribes imposing pay-or-stay sentences, requiring forfeiture of confiscated money, or jailing people to collect unpaid court debt (Biloxi Munic. Court 2016). In terms of policy impact, the bench card idea is proving to be an influential one. In early 2017, the National Taskforce on Fines and Fees, initially crafted by the Obama DOJ and comprising members from the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) and the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA), voted to create their own national bench card and establish a policy that encourages nationwide judicial training in the use of the bench card (Montgomery 2017).

A prime example of proactive and significant policy change occurred in Alameda County, California. The Board of Supervisors there voted unanimously to cease charging fees to families with children in the juvenile justice system (Resolution 2016-66) (Alameda Cty. Board Superv. 2016). Before the ban, families were routinely charged fees, including $25 per night in juvenile hall, a $15 daily fee for ankle monitoring, and a $300 public defender fee (Valle & Carson 2016). Unpaid fees became civil judgments, which could result in parents’ wages being garnished, their bank accounts being levied, and their tax refunds being intercepted (Alameda Cty. Board Superv. 2016). The Board of Supervisors had implemented the fees in 2009 as a way to offset increasing probation costs (Valle & Carson 2016). However, upon closer scrutiny, the county found that it had spent more than $250,000 to collect approximately $420,000 from an estimated 300 families (Valle & Carson 2016). The California legislature is considering a bill (SB 190; http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/biLlTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB190) to extend similar protections statewide in the 2017–2018 session.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Given the growing national attention now being paid to monetary sanctions, we need more research to better understand a variety of related issues, including the factors that influence the sentencing of monetary sanctions at the ecological and individual levels, the collateral consequences of court-ordered debt for individuals and their families, how jurisdictional-level legislative differences foster structural forms of inequality between states and locales, the effects of monetary sanctions on recidivism, and how systems of monetary sanctions intersect with other modes of punishment and social institutions beyond the criminal justice system. In this section, we highlight some aspects of monetary sanctions most urgently requiring sustained scholarly attention.

The Possibilities of Proportional Punishment

In the United States, fines are typically one of an offender’s many monetary sanctions, and they rarely replace incarceration or supervision, particularly for felony offenses. In addition, statutorily mandated fines, fees, and surcharges are not adjusted to ability to pay and do not necessarily reflect the severity of the offense (for a full discussion, see Gist 1996). The use of fines in other countries takes an entirely different approach. First, day fines are often used as a complete substitution for incarceration or supervision (as opposed to supplementing them) and are often the default sanction (Kantorowicz-Reznichenko 2015). Second, day fines are calculated based on both an offender’s financial situation (typically by calculating a percentage of income) and the severity of the offense (e.g., Hillsman & Mahoney 1988, Greene 1988). Tailoring the sanction to the individual avoids many of the deleterious effects of the system of monetary sanctions in the United States, which routinely ignores ability to pay.

It follows that offenders in day-fine countries are at much less risk of being drawn into a protracted, disproportionate, and harmful system of punishment. Because taking into account the burden on the offender is explicitly part of their rationale, day fines are a superior method for maintaining equality before the law (for a full discussion, see Kantorowicz-Reznichenko 2015). Indeed, the example of Germany (the country with the most extensive day-fine system) indicates that day fines seem to be impervious to demographic changes, which is often a precursor to harsher crime policy (Frase 2001). As such, day fines are an effective punishment that generates income, but they do so without undermining the core principles of effective criminal justice policy (Frase 2001, Martin et al. 2016).

The United States has some experience with day fines. During the heyday of developing alternative sanctions in the 1980s and 1990s, several initiatives were launched to explore the viability of proportional fines. The results were largely promising. A RAND study of these day fines in Arizona (Maricopa County) focused on felony offenders “with low need for supervision and treatment” (Turner & Greene 1999, p. 1). It found that day fines successfully diverted people from standard supervision probation, and increased payment, without negative consequences in arrests and technical violations (Turner & Greene 1999). A study funded by the National Institutes of Justice (1992) tested day fines in Milwaukee and Staten Island and found similarly positive results, but it was limited to low-level courts. However, a similar effort to test day fines in Ventura County, California faltered because of a set of problems deemed to be intractable at the time, such as securing adequate staffing and obtaining the data necessary to monitor and evaluate the program (Mahoney 1995).

It is important to note that although proportionality has only been applied to fines, the principle could be used effectively with fees and surcharges as well. Doing so would entail legislative action that allowed for factoring ability to pay into monetary sanctions such as felony surcharges or fees for DNA testing. This type of intervention is well-suited for testing in a small number of jurisdictions (for legislation) or courthouses (for specific fines, fees, and surcharges). In sum, there is both reason for optimism and valuable experience on which to draw to more closely align the current US system of monetary sanctions with the day-fine model. Indeed, by taking into account both offense severity and ability to pay, the day-fine model could help address the most pressing concerns of our current system of monetary sanctions.

Enforcement and Collection of Monetary Sanctions

Enforcing and collecting monetary sanctions increases the bureaucracy needed to administer criminal justice and widens the field of stakeholders and actors beyond just the courts. Although monetary sanctions such as fees and surcharges are ostensibly assessed to provide revenue and recoup system costs, we do not currently know whether states and local jurisdictions are actually netting revenue over and above the costs of collection. Some states charge interest on unpaid debt, and many state laws allow courts and local governments to contract with private collections agencies that typically charge a collection fee (Harris et al. 2016). Given the broad array of enforcement mechanisms and collateral consequences (e.g., tax rebate interception, liens, wage garnishment, etc.) coupled with the sizable between- and within-state variation, a key question is how well current policy achieves both efficiency and fairness. That is, are the financial and social costs of our current systems of collection worth the revenue produced?

Another pressing issue scholars need to address is the extent of dependence on revenue from monetary sanctions. Because jurisdictions claim they rely on LFO revenue, this question should be addressed at both the municipal and state levels. Many states have complicated systems of divvying up the money from fines, fees, surcharges, and even restitution. Tracking where the money goes is difficult. For instance, Nevada splits its administrative assessment ($30–$120) on every misdemeanor among the county treasurer, municipal courts, and the state general fund, with the remainder being split 51/49 between the courts and a variety of criminal justice–related programs (Martin 2017). Mississippi, meanwhile, has more than forty criminal assessments on traffic violations, misdemeanors, and felonies that help fund everything from the DuBard School for Language Disorders Fund to prosecutors’ salaries (Miss. Code § 99–19–73). On the one hand, monetary sanctions support many very worthwhile endeavors (crime victim compensation funds chief among them). On the other hand, the structures in place foster a myopic focus on revenue while largely shielding decision-makers from the short- and long-term costs entailed in actually collecting this revenue. The question of whether the benefits truly outweigh the costs remains rich ground to be broken in this domain.

Alternatively, but just as important, researchers are beginning to ask about the costs incurred by the current system. Social costs are one type of cost warranting close investigation. Although scholars have begun to document the negative consequences for failure to pay court debt (e.g., Harris et al. 2016), two unanswered questions rise to the top of the list in terms of urgency. The first is the question of effects on families. By one recent estimate, people leaving prison do so with an estimated $13,000 in court-ordered debt (deVuono-Powell et al. 2015). Research on the effects of incarceration on legal bystanders (Comfort 2008) has compelling analogs in monetary sanctions. Indeed, the fact that people other than the person sentenced can serve a monetary sanction instead means that the potential for others to be caught up in paying the debt is particularly high (Comfort 2016, Harris 2016). Moreover, given that justice-involved people are already more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged, the extent to which court-ordered debt further stresses familial stability demands rigorous inquiry (Harris et. al. 2017).

Related to this topic is the question of how, precisely, criminal justice debt affects the reentry process. Although we know that failure to pay monetary sanctions can pose a significant barrier to reentry (Bannon et al. 2010), the literature would benefit greatly from more robust qualitative work that brings to light the meaning people (i.e., debtors and their families) make of their debt. Given that the diffuse effects of criminal justice debt on families and communities are likely substantial, crafting policy that minimizes disproportionate harm requires assiduous analysis of these effects.

Finally, the field needs research on the criminogenic effects of criminal justice debt. Common sense and anecdotal evidence suggest that saddling justice-involved people with criminal justice debt may decrease the likelihood of desistance from crime. Not only are justice-involved people more likely to have socioeconomic and educational disadvantages, but the stigma of a criminal record is known to limit employment options (Ewert et al. 2014, Pager 2007, Pettit 2012, Pettit & Western 2004). Thus, rather than supporting the complete reintegration into society postincarceration, monetary sanctions constitute yet another hurdle people must clear.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

“Unless ticket writing ramps up significantly before the end of the year, it will be hard to significantly raise collections next year…Given that we are looking at a substantial sales tax short fall, it’s not an insignificant issue” (US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015, p. 2).

“Court fees are anticipated to rise about 7.5%. I did ask the Chief if he thought the PD could deliver 10% increase. He indicated they could try” (US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015, p. 2).

Lowering this cap is not new in Missouri: In 1999, the Missouri General Assembly passed “Macks Creek Law,” which capped the amount municipalities (with a municipal court division) could receive from traffic fines at 45%; in 2009 the cap was lowered to 35%, and lowered again to 30% in 2013.

SB 5 also reduced the cap in St. Louis County to 12.5%. The lower cap for St. Louis County was later challenged in court. A city judge later struck down the lower cap for St. Louis, which is now being appealed.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adamson CR. 1983. Punishment after slavery: southern state penal systems, 1865–1890. Soc. Probl 30(5):555–69. http://socpro.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2307/800272 [Google Scholar]

- Alameda Cty. Board Superv. 2016. Resolution No. 2016-66: a resolution placing a moratorium on the assessment and collection of all juvenile probation fees and the juvenile public defender fee. March 29 [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union. 2010. In For A Penny. The Rise of America’s New Debtors’ Prisons. New York: ACLU. https://www.aclu.org/report/penny-rise-americas-new-debtors-prisons [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union. 2015a. Debtors’ Prisons. New York: ACLU. https://www.aclu.org/issues/racial-justice/race-and-criminal-justice/debtors-prisons [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union. 2015b. LD 951 Will End Jail Time for Being Too Poor to Pay Fines. New York: ACLU. https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-maine-calls-legislature-end-debtors-prisons [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union. La. 2015. Louisiana’s Debtors Prisons: An Appeal to Justice. New Orleans, LA: ACLU La. https://www.laaclu.org/en/publications/louisianas-debtors-prisons-appeal-justice [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union. Wash. Columbia Leg. Serv. 2014. Modern-Day Debtors’ Prisons: The Ways Court-Imposed Debts Punish People for Being Poor. Seattle, WA: ACLU Wash. http://www.columbialegal.org/sites/default/files/ModernDayDebtorsPrison.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Back Road Calif. 2016. Stopped, Fined, Arrested: Racial Bias in Policing and Traffic Courts in California. BOTRCA. http://www.lccr.com/wp-content/uploads/Stopped_Fined_Arrested_BOTRCA.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bannon A, Nagrecha M, Diller R. 2010. Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Reentry. New York: New York Univ. School Law Brennan Cent. Justice [Google Scholar]

- Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983)

- Beckett K, Harris A. 2011. On cash and conviction: monetary sanctions as misguided policy. Criminol. Public Policy 10(3): 509–37 [Google Scholar]

- Bersani B, Chapple C. 2007. School failure as an adolescent turning point. Sociol. Focus 40:370–91 [Google Scholar]

- Biloxi Munic. Court. 2016. Biloxi Municipal Court Procedures for Legal Financial Obligations & Community. Biloxi, MS: Biloxi Muni. Court [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon DA. 2009. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books. 1st ed. [Google Scholar]

- Blakke D 2009. Payment of court-related fees, charges, costs, fines, and other monetary penalties in hillsborough county. Annu. Assess. Collect. Rep, Hillsborough Cty. Clerk Courts, Tampa, FL [Google Scholar]

- Bur. Justice Stat. 1997. Criminal Justice System Flowchart. Washington, DC: US Dep. Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/largechart.cfm [Google Scholar]

- Comfort M 2008. Doing Time Together: Love and Family in the Shadow of the Prison. Chicago, IL: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Comfort M 2016. A twenty-hour-a-day job: the repercussive effects of frequent low-level criminal justice involvement on family life. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci 665:63–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deVuono-Powell S, Schweidler C, Walters A, Zohrabi A. 2015. Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families. Oakland, CA: Ella Baker Cent. Forw. Together Res. Action Des. http://whopaysreport.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ewert S, Sykes B, Pettit B. 2014. The degree of disadvantage: incarceration and inequality in education. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci 651:24–43 [Google Scholar]

- Frase RS. 2001. Sentencing in Germany and the United States: Comparing Äpfel with Apples. Freiburg im Breisgau, Germ.: Max-Planck-Inst. For. Int. Crim. Law [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen A, Lassiter L. 2016. Disenfranchised by Debt: Millions Impoverished by Prison, Blocked from Voting. Seattle, WA: Alliance Just Soc. http://allianceforajustsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Disenfranchised-by-Debt-FINAL-3.8.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gist NE. 1996. How to use structured fines (day fines) as an intermediate sanction. Bur. Justice Assist. Rep. NCJ 156242, US Dep. Justice, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MA, Glaser D. 1991. The use and effects of financial penalties in municipal courts. Criminology 29(4):651–76 [Google Scholar]

- Gov. Account. Office (GAO). 2015. State and local governments’ fiscal outlook, 2015 update. GAO Rep. GAO-16-260SP, GAO, Washington D.C. http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/674205.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Green E 1961. Judicial Attitudes in Sentencing. New York: St. Martin’s Press [Google Scholar]

- Greene J 1988. Preliminary Data Report: Day-Fine Pilot Project. New York: VERA Inst. Justice. https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/preliminary-data-report-day-fine-pilot-project/legacy_downloads/1524b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hager E 2015. Debtors’ Prisons, Then and Now: FAQ. New York: Marshall Proj. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2015/02/24/debtors-prisons-then-and-now-faq [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Huebner B, Martin K, Pattillo M, Pettit B, et al. 2017. Debtors’ Experiences with Monetary Sanctions. New York: Laura John Arnold Found. In press [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Huebner B, Martin K, Pattillo M, Pettit B, et al. 2016. Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions. New York: Laura John Arnold Found. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A 2016. A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Evans H, Beckett K. 2011. Courtesy stigma and monetary sanctions: toward a socio-cultural theory of punishment. Am. Sociol. Rev 76(2):234–64 [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Evans H, Beckett K. 2010. Drawing blood from stones: legal debt and social inequality in the contemporary United States. Am. J. Sociol 115(6):1753–99 [Google Scholar]

- Hartney C, Vuong L. 2009. Created Equal: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the US Criminal Justice System. Oakland: Natl. Counc. Crime Delinq. http://www.nccdglobal.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/created-equal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harvey T, McAnnar J, Voss MJ, Conn M, Janda S, Keskey S. 2014. ArchCity Defenders: Municipal Courts White Paper. St. Louis:ArchCity Defenders. http://www.archcitydefenders.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/ArchCity-Defenders-Municipal-Courts-Whitepaper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hillsman S 1990. Fines and day fines. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, Vol. 12, ed. Tonry M, Morris N. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Hillsman ST, Mahoney B. 1988. Collecting and enforcing criminal fines: a review of court processes, practices, and problems. Justice Syst. J 13:17–36, 90–92 [Google Scholar]

- Hitt J 2015. Police shootings won’t stop unless we also stop shaking down black people: the dangers of turning police officers into revenue generators. Mother Jones, Sep-Oct, http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/07/police-shootings-traffic-stops-excessive-fines/ [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg A 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Kantorowicz-Reznichenko E 2015. Day fines: Should the rich pay more? Rev. Law Econ 11:481–501 [Google Scholar]

- Kleck G 1981. Racial discrimination in criminal sentencing: a critical evaluation of the evidence with additional evidence on the death penalty. Am. Sociol. Rev 46(6):783–805 [Google Scholar]

- Knowles D 2015. Broke because of traffic ticket revenue drop: the news that the court faces a $1.4 million shortfall comes amid a debate over the role of municipal violations. Bloomberg Politics, March 24 [Google Scholar]

- Maass D 2016. “No cost” license plate readers are turning Texas police into mobile debt collectors and data miners. Electronic Frontier Foundation, January. 26, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/01/no-cost-license-plate-readers-are-turning-texas-police-mobile-debt-collectors-and [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney B July 1995. The Ventura Day Fine Pilot Project: A Report on the Planning Process and the Decision to Terminate the Project, With Recommendations Concerning Future Development of Fines Policy. Denver, CO: Justice Management Institute [Google Scholar]

- Mawajdeh H 2016. New license plate reader could make Texas cops debt collectors, too. Texas Standard, Febr. 2, http://www.texasstandard.org/stories/new-license-plate-reader-could-make-texas-cops-debt-collectors-too/ [Google Scholar]

- Martin K 2018. Monetary myopia: an examination of institutional response to revenue from monetary sanctions for misdemeanors. Crim. Justice Policy Rev In press [Google Scholar]

- Martin K, Smith SS, Still W. 2016. Shackled to debt: criminal justice financial obligations and the barriers to reentry they create. New Think. Commun. Correct. Bull, Natl. Inst. Justice, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- McLean R, Thompson M. 2007. Repaying Debts. New York: Counc. State Gov. Justice Cent. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell O 2005. A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. J. Quant. Criminol 21:439–66 [Google Scholar]

- Miss. Code § 99–19–73 (2015)

- Montgomery L 2017. National Task Force of Judicial Leaders Releases Resources to Aid State Courts. Williamsburg,VA: Natl. Cent. State Courts. http://www.ncsc.org/Newsroom/News-Releases/2017/Fines-Fees-Task-From-Resources.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Morris N, Tonry MH. 1990. Between Prison and Probation: Intermediate Punishments in a Rational Sentencing System. New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Natl. Inst. Justice. 1992. Day fines in American courts: the Staten Island and Milwaukee experiments. Natl. Inst. Justice Rep. NCJ 136611, US Dep. Justice, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Nieto M 2006. Who Pays for Penalty Assessment Programs in California? Sacramento, CA: Calif. Res. Bur. [Google Scholar]

- Office City Audit. 2011. Report to the City Council: City of San Jose. Traffic citation revenue: revenue has declined over the last five years and the city continues to receive a small share of the revenue. City Audit. Rep 11–06, Office City Audit., San Jose, CA [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P 2009a. The Currency of Justice: Fines and Damages in Consumer Societies. NewYork, NY: Routledge-Cavendish [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P 2009b. Theorizing Fines. Punishm. Soc. 11(1):67–83 [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P 2011. Politicizing the case for fines. Criminol. Public Policy 10(3):547–53 [Google Scholar]

- Oshinsky DM. 1997. “Worse than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. 1. ed. New York: Free Press [Google Scholar]