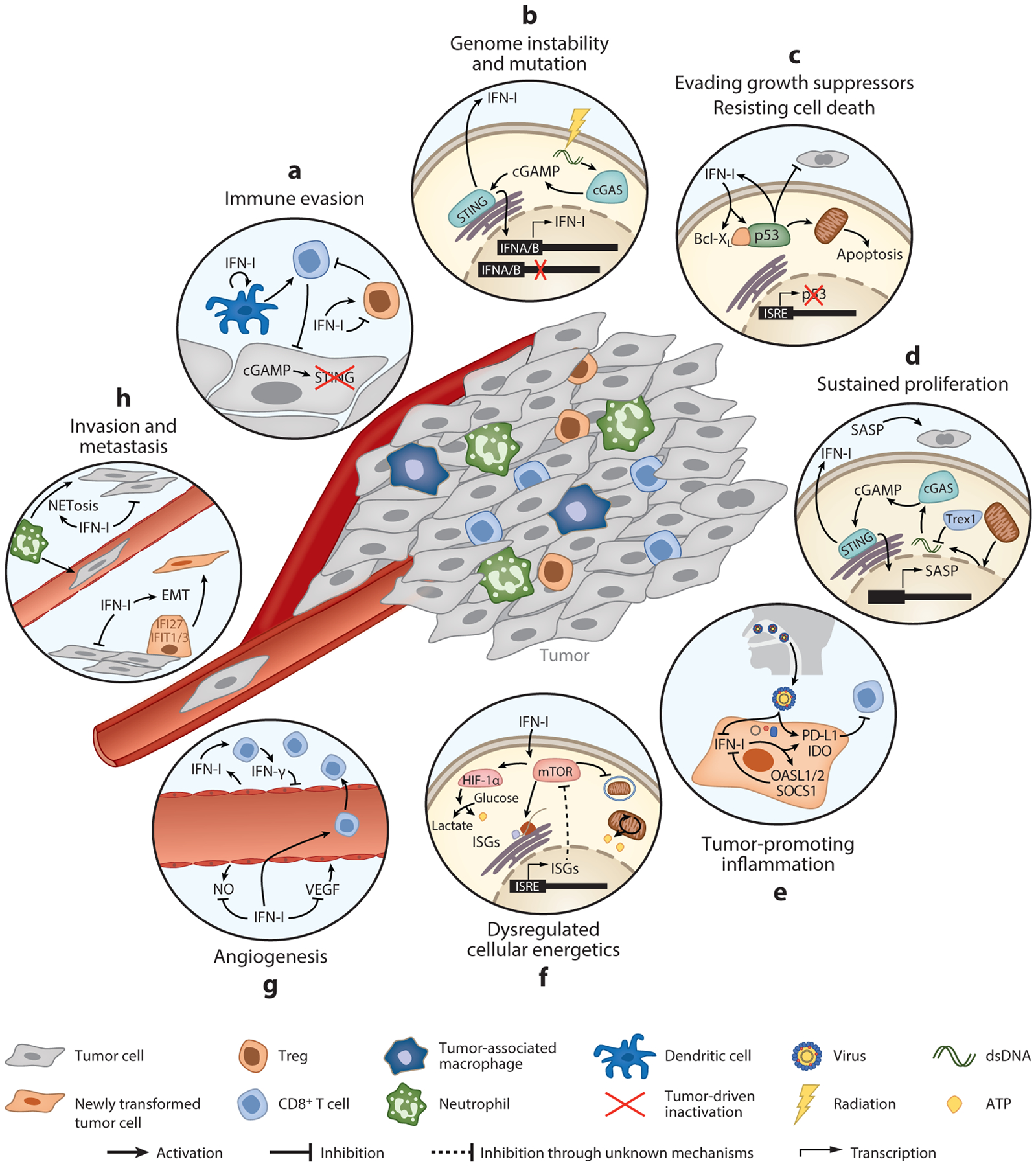

Figure 2.

IFN-I-mediated regulation of the hallmarks of cancer. Key pathways highlighting examples of the opposing roles in IFN-Is in different pathological processes during cancer development. (a) Immune evasion. Inactivation of STING or IFNAR blunts IFN-I production, limiting the ability of dendritic cells to prime T cell responses and enhancing Treg infiltration. Cancer cells can also co-opt IFN-Is to promote Treg function in the tumor microenvironment. (b) Genome instability and mutation. DNA damage induced by accumulated mutations or by radiation therapy stimulates IFN-I responses through cGAS-STING-mediated expression of ISGs. IFN-Is are also commonly mutated in cancer. (c) Evading growth suppressors/resisting cell death. Mutual activation of IFN-Is and p53 inhibits tumor cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Tumors can overcome these effects by mutating p53. (d) Sustained proliferation. STING activated in senescent cells upregulates IFN-I and SASP. While senescent cells are replicatively paralyzed, SASP can promote tumor growth. (e) Tumor-promoting inflammation. Chronic inflammation caused, for example, by viral infection induces a skewed IFN-I response, favoring the expression of negative regulatory ISGs that facilitate continued tumor growth. (f) Dysregulated cellular energetics. Through regulation of mTORC1, IFN-Is activate glycolysis or autophagy, either of which promotes tumor cell growth and survival. (g) Angiogenesis. IFN-Is inhibit VEGF and promote vascular normalization, allowing T cell infiltration and antitumor immunity. (h) Invasion and metastasis. IFN-Is can facilitate EMT and also promote inflammation at distal sites that enhance metastasis. Abbreviations: EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; IFNAR, IFN-α/β receptor; ISG, IFN-stimulated gene; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.