Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 preferentially targets the human’s lungs, but it can affect multiple organ systems. We report a case of cardiorenal syndrome in a 37-year-old man who had symptoms of fever, myalgia and cough. He tested positive for COVID-19 and presented 5 days later with acute heart failure. Work up was done including echocardiography showing reduced ejection fraction. Later in the hospital course he developed acute renal failure and was treated with intermittent renal replacement therapy. No other definite cause of cardiorenal complications was identified during the course of the disease. A possible link with COVID-19 was considered with underlying mechanisms still needed to be explored. This case highlights the potential of SARS-CoV-2 affecting heart and kidneys. The disease not only involves the organs directly but can exacerbate the underlying comorbid illness.

Keywords: COVID-19, heart failure, renal system, infectious diseases

Background

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified during an outbreak of respiratory illness in Wuhan, China. COVID-19 rapidly evolved into a global pandemic and was declared as health emergency by WHO in March 2020. The COVID-19 disease presentation is variable and heterogenous, ranging from asymptomatic carriers to serious illness like acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan failure and death.1 Interestingly, the disease involves multiple organs like the heart, kidneys and brain at an initial stage of the disease, although being linked to the respiratory system predominantly.2

The pre-existing and newly developed cardiovascular diseases are common in patients with COVID-19 disease and are associated with severity of the disease and high mortality.3 According to recent epidemiological study,4 the coronavirus infection can cause acute myocardial injury, arrythmia and shock in 7.2%, 18.7% and 8.7% patients, respectively. Renal involvement is also frequent in the course of COVID-19. About 40% or greater number of cases have abnormal proteinuria during hospital admission.5 Among the critically ill patients, acute kidney injury (AKI) is common affecting approximately 20%–40% of patients in the intensive care units in Europe and USA.6

The term cardiorenal syndrome is used for a number of conditions related to renal and cardiovascular system in which an acute or chronic insult of one organ system can cause dysfunction of the other organ system.7 SARS-CoV-2 binds to human ACE2 as entry route to human pneumocytes.8 The expression of ACE2 in the heart and kidneys explains the link between COVID-19 and the renal and cardiovascular system. Therefore, extrapulmonary cardiorenal manifestations can be seen due to renin–angiotensin system dysfunction secondary to coronavirus infection. These can include arrythmias, acute cardiac and renal injury thus leading to secondary cardiorenal syndrome.

With this case report, we highlight the atypical presentation of COVID-19 disease in the form of cardiorenal manifestations. Further research studies are critical to explore the underlying pathological mechanisms and find the ways of early diagnosis and treatment in order to decrease the mortality.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 37-year-old male healthcare worker, who had a history of close contact with a recently diagnosed patient with COVID-19 disease. Four to five days after the exposure, he started having typical symptoms of COVID-19 including high-grade fever, myalgia and dry cough. He was a non-smoker and his medical history was unremarkable except for ureteric calculi. He tested positive for COVID-19 on day 7 after the contact. Therefore, he was advised to self-isolate at home with close observation of his symptoms.

A few days later, he developed worsening shortness of breath and was advised to come to the hospital. On examination, he was noted to have bibasal crackles with gallop rhythm of the heart and resting tachycardia. There were no signs of pedal oedema. Besides the clinical examination initial investigations including complete blood count, renal and liver profile, cardiac troponins, ECG and chest X-ray were advised. In view of the suspicion of heart failure an echocardiography was planned.

Investigations

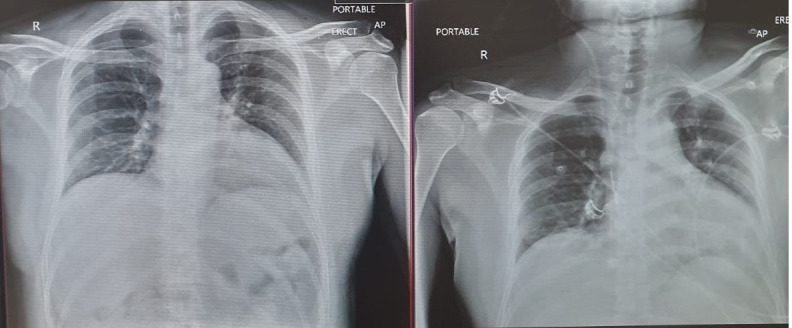

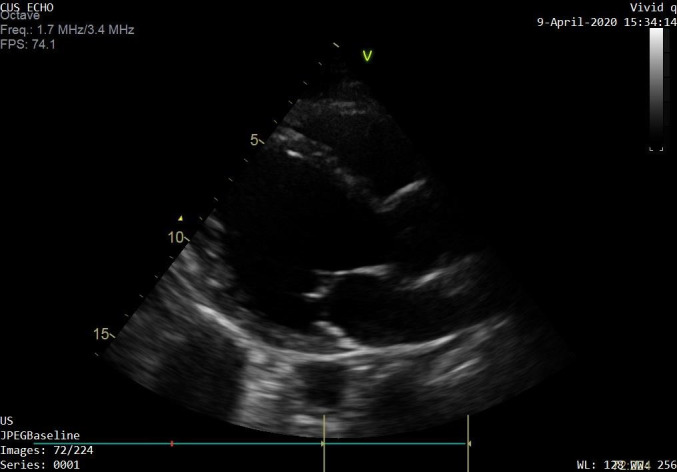

The patient’s initial investigations revealed lymphopaenia, raised C reactive protein (CRP) of 74 mg/L, lactate dehydrogenase of 303 U/L and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of 247 pg/mL. BNP levels between 100 pg/mL and 400 pg/mL with clinical suspicion indicating probable heart failure. Liver function tests were mildly deranged with bilirubin 5 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 50 U/L, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 82 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 53 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 29 U/L, however, the rest of the blood tests including haemoglobin, total white cell count, electrolytes and renal function were within normal range. Cardiac troponins were negative and ECG showed sinus tachycardia. The chest X-ray showed minimal bibasal infiltrates (figure 1). The transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed an eyeball ejection fraction estimate of 10%–15% and dilated left ventricle with left ventricular (LV) dimensions calculated as LV internal diameter end diastole of 7.1 cm and LV internal diameter end systole of 6.3 cm (figure 2 and video 1).

Figure 1.

Chest X-rays showing minimal bibasal infiltrates.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography showing severe left ventricular dilatation (day 5 COVID-19).

Video 1A.

Video 1B.

Video 1C.

Later, serial cardiac troponins, ECGs and TTE were ordered to monitor the heart function as illustrated in table 1.

Table 1.

Serial cardiac imaging, ECGs and troponin levels

| Day since admission | Day 0 (echocardiography) |

Day 5 (echocardiography) |

Day 21 (echocardiography) |

Day 86 (cardiac MRI) |

| LVEF (%) | 10–15 | 25–30 | 35–40 | 46 |

| LV function | Impaired | Impaired | Improved LV function | Impaired |

| LV | Severely dilated | Moderately dilated | Mildly dilated | Mildly dilated |

| Troponin T* | <5 ng/mL | <5 ng/mL | <5 ng/mL | – |

| ECG | Sinus tachycardia | Sinus tachycardia | Sinus rhythm | – |

**Reference value: troponin (0–14 ng/mL).

LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Interestingly, there was no significant rise in the cardiac troponin levels and ECG results showed persistent sinus tachycardia with occasional premature ventricular contractions and no signs of ischaemia. A gradual improvement in the ejection fraction was noted as the patient reported improvement in his shortness of breath on day 14 after the COVID-19 diagnosis. A follow-up cardiac MRI was ordered due to the suspicion of underlying viral cardiomyopathy. Cardiac MRI showed moderate LV impairment with modest dyssynchrony but interestingly no obvious evidence for myocardial fibrosis. Pre-COVID-19 pre-existing cardiomyopathy was considered.

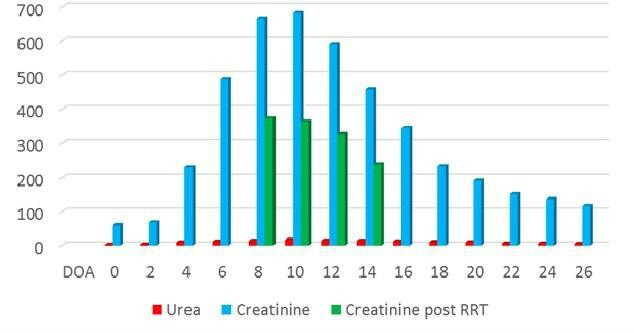

During the initial management of COVID-19 and possible cardiomyopathy without obvious cause, the patient had high-grade temperature spikes (39°C–40°C) with CRP <100 mg/L. He was initially prescribed ceftriaxone considering bacterial superinfection, although his blood and urine cultures were negative. Three days later, his CRP started creeping up with no significant improvement in fever spikes. Ceftriaxone was then changed to piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin added to cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In next 2–3 days, the patient’s renal functions started deteriorating with gradual worsening of creatinine clearance. Vancomycin levels were checked and found to be within normal range. The renal functions kept on deteriorating even when the patient was off the vancomycin and his creatinine clearance (GFR) became <10 mL/min/1.73 m2 with a creatinine of 657 μmol/L (figure 3). He became oliguric and started on intermittent haemodialysis. As a result, a renal biopsy was planned which showed acute tubular injury with some granular casts and some localised inflammation around injured tubules. Extensive investigations by the nephrology colleagues resulted in the impression that it was a case of acute tubular necrosis/tubular injury either viral or drug induced with no glomerular change on light microscopy. The patient received vancomycin for 3 days not exceeding 4 g/day. Studies have demonstrated the strong relationship between AKI and measures of vancomycin exposure. In this regard, longer duration of therapy exceeding 7 days or a daily dose of vancomycin in excess of 4 g correlate with higher risk of nephrotoxicity in multiple studies.9

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of renal functions during hospital admission. Note: DOA (day of admission), urea (mmol/L), creatinine (mmol/L). RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Differential diagnosis

The initial clinical suspicion pointed to a case of COVID-19-induced myocarditis, but negative cardiac troponins, nil significant changes in the ECGs and later follow-up cardiac MRI report ruled out this condition. The renal insult was considered to be secondary to drugs or bacterial superinfection. Renal function continued to deteriorate despite correcting the underlying causes. The requirement for intermittent haemodialysis and renal biopsy results led to think about a possible link with COVID-19 as underlying mechanisms are still needed to be explored.

The patient had cardiorenal complications during the course of COVID-19 with no other cause found. Pre-COVID-19 pre-existing cardiomyopathy was considered in the differentials with evolution of the ejection fraction.

Treatment

The initial treatment given to the patient was supportive and symptomatic. He was kept in a COVID-19 isolation room. Regarding the clinical suspicion of viral cardiomyopathy, he was started on low-dose beta blocker and an ACE inhibitor drug. The ACE inhibitor was held when renal functions started worsening and monitoring of heart function was carried out with serial ECGs and TTEs. The patient was given intravenous antibiotics on suspicion of bacterial superinfection, initially ceftriaxone and later piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin. With renal function deterioration, vancomycin was stopped with monitoring of vancomycin levels. The patient had intermittent renal replacement therapy (RRT) using standard haemodialysis machine in the conventional intermittent haemodialysis mode for 8 days as his creatinine clearance decreased to levels below 10 mL/min. Renal functions were monitored along with daily volume input–output record. The patient was kept in the intensive care unit till he recovered from acute renal insult.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient showed significant improvement prior to discharge as he was symptom free. Echocardiography showed that his ejection fraction had increased to 25%–30% (video 2) and his renal function was improving (see figure 3). His kidney functions recovered as he was no longer oliguric and in need of dialysis.

Video 2.

The patient was advised to self-isolate in accordance with Health Services Executive Ireland guidelines and booked for a follow-up in the heart failure clinic in 1 month time and renal clinic after 6 weeks.

Follow-up cardiac MRI showed an ejection fraction (EF) of 46% with moderate LV impairment and renal function was within normal range.

Discussion

In a meta-analysis and systemic review, acute cardiac injury with a frequency of 25.3% was the most reported cardiac complication of COVID-19 disease. Considering the cardiorenal interactions, AKI was stated in 8.8% of studies included in this meta-analysis.10 Various studies have documented cardiac involvement in COVID-19 with complications like myocarditis,11 acute myocardial infarction12 and exacerbation of heart failure.1 13 14 The kidneys are affected as sequelae of direct cellular injury,15 sepsis or cytokine storm in COVID-19. Previous studies of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome-associated coronaviruses showed a prevalence of acute renal insult (AKI) of 5%–15%.16 Early studies involving patients with COVID-19 suggested a lower incidence of AKI of 3%–9%. These studies conducted on Chinese patients4 and the most predominant abnormalities were albuminuria or haematuria on the first day of admission. Abnormal renal function tests including elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels were found in 15.5% and 14.1% of patients, respectively.5 The incidence of AKI was associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality.

There was no direct antiviral therapy approved or recommended at the time the patient presented to the hospital. A number of investigational agents including remdesivir were being tested or under trial for antiviral treatment of COVID-19. The main critical care goals recommended included avoidance of fluid overload, maintenance of blood pressure and good oxygenation. Renal treatment goals included supportive therapy and RRT16 if needed. The question of considering when to start RRT was still unclear and a matter of debate. The type of RRT in acute renal failure associated with patients with COVID-19 is another unanswered query. We could extrapolate the results from the population without COVID-19, where there is no difference in outcomes for early versus late start of RRT.8 Similarly based on data from patients without COVID-19, intermittent dialysis is an acceptable treatment option in AKI associated with COVID-19 disease.

There is no data supporting a COVID-19 related shift away from angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) in patients with heart failure. According to the Position Statement of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension17 and a joint statement from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association and Heart Failure Society of America posted online on 17 March 2020,18 holding these medications can worsen the cardiac status and overall COVID-19 outcome. A meta-analysis published in European Heart Journal provides reassurance that each of ACE inhibitors and ARBs are safe in context of COVID-19 and should not be discontinued.19 A recent randomised controlled trial (BRACE CORONA) provides evidence that there is no clinical benefit from routinely suspending ACE inhibitors or ARBs in hospitalised patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.20 Based on these guidelines, ACE inhibitor was prescribed considering the cardiac involvement and it was held temporarily only during the acute renal insult.

The knowledge on COVID-19 is evolving and new evidence-based information is published on a daily basis. This case report highlights that cardiorenal complications can occur in COVID-19. The aetiology is multifactorial, and management is supportive, with possible need of RRT. Large-scale clinical trials can help inform optimal management of AKI in COVID-19, and more retrospective data on clinical experience is required to assess the impact and prognosis of patients with COVID-19 with pre-existing heart diseases.

Patient’s perspective.

The time of my illness of COVID-19 was the worst period of my life. I initially kept my mind positive and hoped to win this battle, but when the things got worse, I got scared and depressed. I would like to say special thanks to the medical team who kept giving me the hope and kind help which I needed at that particular stage. I think it was a miracle of God, Who gave me a second chance to live through the great services of the medical team and support of my family and friends.

Learning points.

COVID-19 is not only a pulmonary disease, it also affects the kidneys and the heart and, therefore better described as a multisystemic entity.

Breathlessness in COVID-19 disease can be non-respiratory and related to acute myocarditis, cardiomyopathy or exacerbation of heart failure.

The objective of this article is to highlight the atypical presentation of cardiorenal complications in COVID-19 disease.

Further research studies are critical to explore the underlying pathological mechanisms and find the ways of early diagnosis and treatment in order to decrease the mortality.

Footnotes

Contributors: Dr MSS gave the idea to present the case summary. He found the clinical case quite interesting in the light of current COVID-19 pandemic. He discussed the plan with Dr UAA. Both Dr MSS and Dr UAA conducted the review of the available literature to find if there are similar case reports published already and what is known so far with reference to the topic under discussion. Both authors reported the results from available studies to one of the senior colleague (consultant in infectious disease) and sought the advice. They finalised the topic of the case report after discussion with the consultant. Dr MJY was very familiar with the case. He was advised to design the case report after collecting the relevant data and critically analyse the data. Dr UAA performed data acquisition and wrote the relevant sections of the case report with critical analysis and data interpretation. All the authors discussed and finalised the case report after going through all the important steps.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zheng Y-Y, Ma Y-T, Zhang J-Y, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:259–60. 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2352–71. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus–Infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int 2020;97:829–38. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, Blair JEA, et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2019;139:e840–78. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun ML, Yang JM, Sun YP, et al. [Inhibitors of RAS Might Be a Good Choice for the Therapy of COVID-19 Pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:219–22. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanrahan TP, Kotapati C, Roberts MJ, et al. Factors associated with vancomycin nephrotoxicity in the critically ill. Anaesth Intensive Care 2015;43:594–9. 10.1177/0310057X1504300507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Momtazmanesh S, Shobeiri P, Hanaei S, et al. Cardiovascular disease in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10,898 patients and proposal of a triage risk stratification tool. Egypt Heart J 2020;72:41. 10.1186/s43044-020-00075-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2352–71. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tam C-CF, Cheung K-S, Lam S, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006631. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA 2020;323:1612–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tai W, He L, Zhang X, et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol 2020;17:613–20. 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Apetrii M, Enache S, Siriopol D, et al. A brand-new cardiorenal syndrome in the COVID-19 setting. Clin Kidney J 2020;13:291–6. 10.1093/ckj/sfaa082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chu KH, Tsang WK, Tang CS, et al. Acute renal impairment in coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome. Kidney Int 2005;67:698–705. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67130.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. European Society of Cardiology . Position statement of the ESC Council on hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Available: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang

- 18. American College of Cardiology . HFSA/ACC/AHA statement addresses concerns re: using RaaS antagonists in COVID-19. Available: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/03/17/08/59/hfsa-acc-aha-statement-addresses-concerns-re-using-raas-antagonists-in-covid-19

- 19. Grover A, Oberoi M. A systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2021;7:148–57. 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, de Barros E Silva PGM, et al. Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Impact on adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)--The BRACE CORONA Trial. Am Heart J 2020;226:49–59. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]