Dear Editors of journal of infection,

Walsh et al. explored a systemic literature search of viral dynamics of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that prolonged RNA shedding may not represent transmissible live virus and patients were highly unlikely to be infectious beyond 10 days of symptom.1 , 2 On May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) modified the guideline on releasing symptomatic COVID-19 patients from the isolation that patients could be discharged 10 days after the onset of symptoms, plus at least 3 days without symptoms.3 However, this did not differentiate between mild and severe patients and direct measure of infectivity remains uncertain. Virus culture is important to assess the viability and could be a surrogate for transmissibility.2 Thus, this study aimed to trace real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and culture of SARS-CoV-2 from a range of different specimens over the period and to evaluate the contagious period of COVID-19 based on host severity.

We investigated 137 samples from 23 COVID-19 patients hospitalized at Severance Hospital in Seoul, South Korea between February and June 2020. Samples of nasopharyngeal swab, sputum, urine, and rectal swab were collected 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 days after admission. One patient refused additional sample collection. The sample collection of four patients was suspended due to an in-hospital outbreak.

Nasopharyngeal samples were collected in 2 mL viral transport media, while sputum, urine, and stool samples were collected in containers. Samples were subjected to total nucleic acid extraction using a viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The total nucleic acid was recovered using 60 µL of elusion buffer. Real-time RT-PCR assay targeting the three genes (RdRp, N, and E gene) of SARS-CoV-2 was performed with a Seegene Kit (Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay kit, Seegene, Korea). The copy number to construct a standard curve correlated with the cycle threshold (Ct) value. The remaining samples were used for culture. Vero cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Lonza, 12–604F), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, sterile filtered), 100 µg/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 10⁴ cells/well 24 h prior. The 10-fold diluted samples were placed in quadruplicate and incubated at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide. After 4 incubation days, the cytopathic effect was microscopically evaluated. Seven days later, real-time RT-PCR was conducted on 80 μL of infected cell supernatants. The remaining was scraped and transferred to fresh cells in 24-well plates. Cytopathic effect was further monitored for 72 h and virus isolation was confirmed via real-time RT-PCR.

The mean age of the patients was 69.3 years, and 50% of the patients were men (Table S1). Fourteen (77.8%) patients had pneumonia. Six were intubated due to severe pneumonia. The median (InterQuartile Rande, IQR) duration between symptom onset and admission was 3 (2–7.8) days. The patients received treatment following the therapeutic guidelines of the time. Seven (38.9%) patients received steroids while five (27.8%) patients received remdesivir. Three and seven patients underwent lopinavir/ritonavir and convalescent plasma infusion therapy, respectively. Despite intensive medical care, two patients died.

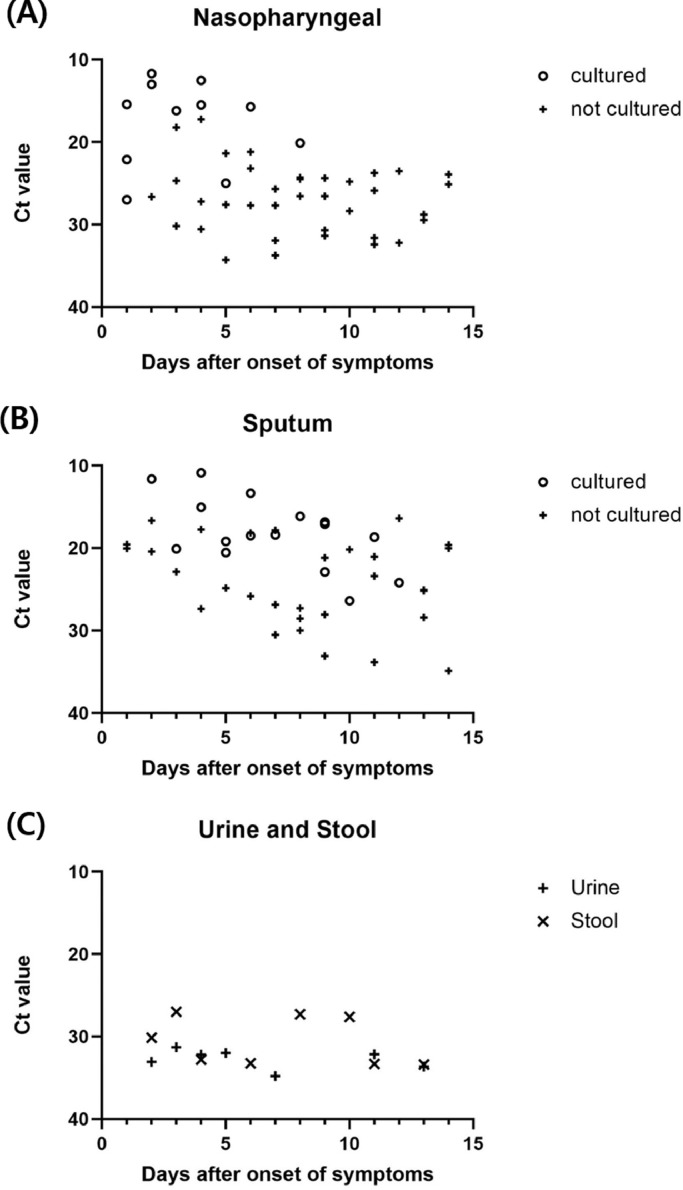

Nasopharyngeal samples were cultured in 11/48 samples (22.9%) and sputum samples were cultured in 16/47 samples (34.0%) (Fig. 1 ). The virus was not isolated in the stool and urine samples. The median (IQR) time from symptom onset to detecting the last viable virus was 3 (1.5–4.5) and 6.5 (4.8–9.0) days for nasopharyngeal swab and sputum samples, respectively. The cultured virus was present up to 12 days after the onset of symptoms. No growth was found for the N gene at a Ct value >23 for nasopharyngeal samples and >27 for sputum samples. The positive culture rate decreased and the Ct value increased over time in nasopharyngeal and sputum samples. In urine and stool samples, the Ct values were relatively high during the early phase of infection and virus isolation was not confirmed.

Fig. 1.

Cyclic threshold (Ct) value of collected samples with culture tests in accordance with the specimens.

Abbreviation: Ct, Cyclic threshold.

Six patients were excluded in the sub-analysis because they were transferred to our center one week after symptom onset, and they continuously tested negative on culture. Another patient was censored due to mortality. The time to viral clearance was defined as the duration between symptom onset and positive to negative culture conversion. Severe COVID-19 patients were classified when the patients applied high flow oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation. The stratified time to viral clearance based on severity and specimens is described in Fig. 2 . For nasopharyngeal samples, the median (IQR) duration was 3.5 (2.3–7.0) and 6 (2.0–6.8) days in the mild and severe groups, respectively. For sputum samples, the median (IQR) duration was 4 (2.0–6.8) and 11 (5.0–14.8) days in the mild and severe groups, respectively. Although the severe group had a longer viral shedding than the mild group, this was insignificant by Mann-Whitney U test (p value = 0.69 and 0.24, in nasopharyngeal swab and sputum samples, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Time to viral clearance in COVID-19 patients.

Abbreviation: ns, no significance.

Our study is generally consistent with previous studies; RT-PCR detected SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs, lower respiratory tract specimens, and rectal swabs, but not in urine samples,4 and the virus could not be isolated from serum, urine, and stool samples although SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected.5 We investigated with different specimens and found that urine and stool were less likely routes for transmission.

There was a negative relationship between the viable virus and Ct value or days after the symptom onset.6 In our study, the presence of all viable viruses in the nasopharyngeal samples was within 10 days after symptom onset. However, the sputum samples of three patients had positive isolated cultures beyond 10 days. Two of the patients were intubated, and one (Patient 6) had a mild fever. Patient 6, who was mildly symptomatic, was still capable of viral shedding 11 days after symptom onset, but showed viral culture conversion 3 days after the fever subsided. Therefore, close monitoring of presenting symptoms, including cough and fever, is warranted. A low Ct value could serve as a marker for detecting the live virus,7 but RT-PCR cannot reflect the presence of an infectious virus. We compared the time from symptom onset to uncultured virus between mild and severe patients. Severe patients had a longer median culturable virus period, without statistical significance. Virus isolation was more likely in patients with severe illness requiring admission to hospital or the ICU compared to outpatients,8 but corticosteroid, immunomodulators, and lopinavir/ritonavir treatment could be associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding.2 , 9 In our study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding and host severity do not identify infectiousness, especially during the later phase of infection. Even though prolonged viral clearance was observed in intubated patients, the virus was no longer viable after 15 days.

Despite small sample size and no inclusion of underlying immunocompromised patients, of whom prolonged live virus shedding and within-host genomic evolution were noted,10 our study suggests that low quantitative SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in a recovered patient is less likely to transmit the infection regardless of severity supporting the present WHO releasing isolation guidelines.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethical review committee of Severance Hospital (No. 4–2020–0076) and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Funding statement

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University, College of Medicine for 2020.

Data for reference

Available on request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.025.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Walsh K.A., Jordan K., Clyne B., Rohde D., Drummond L., Byrne P. SARS-CoV-2 detection, viral load and infectivity over the course of an infection: SARS-CoV-2 detection, viral load and infectivity. J Infect. 2020;81(3):357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh K.A., Spillane S., Comber L., Cardwell K., Harrington P., Connell J. The duration of infectiousness of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020;81(6):847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH . World Health Organization; 17 June 2020. Criteria for Releasing COVID-19 Patients from Isolation: Scientific Brief; p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bwire G.M., Majigo M.V., Njiro B.J., Mawazo A. Detection profile of SARS-CoV-2 using RT-PCR in different types of clinical specimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):719–725. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J.-.M., Kim H.M., Lee E.J., Jo H.J., Yoon Y., Lee N.-.J. Detection and isolation of SARS-CoV-2 in serum, urine, and stool specimens of COVID-19 patients from the Republic of Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(3):112. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jefferson T., Spencer E., Brassey J., Heneghan C. Viral cultures for COVID-19 infectious potential assessment–a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 3 Dec, 2020:ciaa1764. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cevik M., Tate M., Lloyd O., Maraolo A.E., Schafers J., Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(1):e13–e22. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basile K., McPhie K., Carter I., Alderson S., Rahman H., Donovan L. Cell-based culture of SARS-CoV-2 informs infectivity and safe de-isolation assessments during COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 24 Oct, 2020;(1):ciaa1579. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X., Zhu B., Hong W., Zeng J., He X., Chen J. Associations of clinical characteristics and treatment regimens with the duration of viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avanzato V.A., Matson M.J., Seifert S.N., Pryce R., Williamson B.N., Anzick S.L. Case study: prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell. 2020;183(7):1901–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.