The trade-off between different objectives is at the heart of political decision making. Public health, economic growth, democratic solidarity, and civil liberties are important factors when evaluating pandemic responses. There is mounting evidence that these objectives do not need to be in conflict in the COVID-19 response. Countries that consistently aim for elimination—ie, maximum action to control SARS-CoV-2 and stop community transmission as quickly as possible—have generally fared better than countries that opt for mitigation—ie, action increased in a stepwise, targeted way to reduce cases so as not to overwhelm health-care systems.1

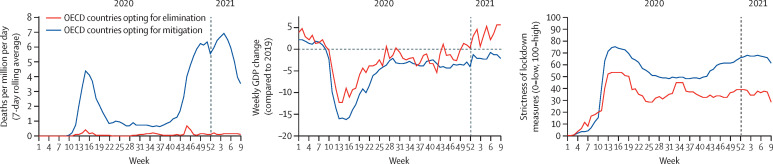

We compared COVID-19 deaths, gross domestic product (GDP) growth, and strictness of lockdown measures during the first 12 months of the pandemic for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries that aim for elimination or mitigation (figure ).2, 3, 4 Although all indicators favour elimination, our analysis does not prove a causal connection between varying pandemic response strategies and the different outcome measures. COVID-19 deaths per 1 million population in OECD countries that opted for elimination (Australia, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea) have been about 25 times lower than in other OECD countries that favoured mitigation (figure). Mortality is a proxy for a country's broader disease burden. For example, decision makers should also consider the increasing evidence of long-term morbidities after SARS-CoV-2 infection.5

Figure.

COVID-19 deaths, GDP growth, and strictness of lockdown measures for OECD countries choosing SARS-CoV-2 elimination versus mitigation

OECD countries opting for elimination are Australia, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. OECD countries opting for mitigation are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the UK, and the USA. Data on strictness of lockdown measures are from Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker.2 Data on COVID-19 deaths are from Our World in Data.3 Data on GDP growth are from OECD Weekly Tracker of economic activity.4 GDP=gross domestic product. OECD=Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

There is also increasing consensus that elimination is preferable to mitigation in relation to a country's economic performance.6 One study quantified the optimal basic reproduction number so that elimination is achieved at minimal economic cost.7 To this end, consider weekly GDP growth with respect to 2019 for the OECD countries that opted for elimination or mitigation (figure). Elimination is superior to mitigation for GDP growth on average and at almost all time periods. GDP growth returned to pre-pandemic levels in early 2021 in the five countries that opted for elimination, whereas growth is still negative for the other 32 OECD countries.

Despite its health and economic advantages, an elimination strategy has been criticised for restricting civil liberties. This claim can be challenged by analysing the stringency index developed by researchers at the University of Oxford.2 This index measures the strictness of lockdown-style policies that primarily restrict people's behaviour by combining eight indicators of containment and closure policies, eight indicators of health system policies, and one indicator of public information campaigns.2 Among OECD countries, liberties were most severely impacted in those that chose mitigation, whereas swift lockdown measures—in line with elimination—were less strict and of shorter duration (figure). Importantly, elimination has been framed as a civic solidarity approach that will restore civil liberties the soonest; this focus on common purpose is frequently neglected in the political debate.

Evidence suggests that countries that opt for rapid action to eliminate SARS-CoV-2—with the strong support of their inhabitants—also better protect their economies and minimise restrictions on civil liberties compared with those that strive for mitigation. Looking ahead, mass COVID-19 vaccination is key to returning to usual life, but relying solely on COVID-19 vaccines to control the pandemic is risky due to their uneven roll-out and uptake, time-limited immunity, and the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants.8, 9 History shows that vaccination alone can neither single-handedly nor rapidly control a virus and that a combination of public health measures are needed for containment. The eradication of smallpox required concerted, decades-long efforts, including vaccination; communication and public engagement; and test, trace, and isolate measures.10 Even at the end of vaccination campaigns, such public health measures must be maintained to some extent or new waves of infections might lead to increased morbidity and mortality.11 With the proliferation of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, many scientists are calling for a coordinated international strategy to eliminate SARS-CoV-2.12, 13, 14, 15 Moreover, the US Department of State declared in April, 2021, that stopping COVID-19 is the Biden–Harris administration's number one priority and highlighted that “this pandemic won't end at home until it ends worldwide”.16

National action alone is insufficient and a clear global plan to exit the pandemic is necessary. Countries that opt to live with the virus will likely pose a threat to other countries, notably those that have less access to COVID-19 vaccines. The uncertainty of lockdown timing, duration, and severity will stifle economic growth as businesses withhold investments and consumer confidence deteriorates. Global trade and travel will continue to be affected. Political indecisiveness and partisan policy decisions reduce trust in government. This does not bode well in those countries that have seen a retraction of democracy.17 Meanwhile, countries opting for elimination are likely to return to near normal: they can restart their economies, allow travel between green zones,18 and support other countries in their vaccination campaigns and beyond. The consequences of varying government COVID-19 responses will be long-lasting and extend beyond the end of the pandemic. Early economic and political gains made by countries aiming to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 will probably pay off in the long run.

Acknowledgments

IK is a member of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board. JVL is a member of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission Public Health Taskforce. DS is a member of the Scottish COVID-19 Advisory Group and the UK Cabinet Office COVID-19 Advisory Group. SV is a member of Team Halo (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the UN, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Baker MG, Wilson N, Blakely T. Elimination could be the optimal response strategy for Covid-19 and other emerging pandemic diseases. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale T, Angrist N, Goldszmidt R, et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker) Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- 4.Woloszko N. OECD; Paris: 2020. Tracking activity in real time with Google Trends. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 2020, no 1634. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, et al. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. published April 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hendren N, et al. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2020. The economic impacts of COVID-19: evidence from a new public database built using private sector data. Working paper no 27431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn F, Khailaie S, Stoeckli M, et al. The common interests of health protection and the economy: evidence from scenario calculations of COVID-19 containment policies. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.14.20175224. published online Aug 16. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aschwanden C. Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature. 2021;591:520–522. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00728-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman D, Loe B, Chadwick A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. published online Dec 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya S. Reflections on the eradication of smallpox. Lancet. 2010;375:1602–1603. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore S, Hill EM, Tildesley MJ, et al. Vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infects Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00143-2. published online March 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priesemann V, Brinkmann MM, Ciesek S, et al. Calling for pan-European commitment for rapid and sustained reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Lancet. 2021;397:92–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priesemann V, Balling R, Brinkman MM, et al. An action plan for pan-European defence against new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Lancet. 2021;397:469–470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00150-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliu-Barton M, Pradelski B, Wolff GB, et al. Aiming for zero COVID-19: Europe needs to take action. 2021. http://www.covid-greenzone.com

- 15.Fontanet A, Autran B, Lina B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;397:952–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blinken AJ. Secretary Antony J. Blinken remarks to the press on the COVID response. US Department of State. April 5, 2021. https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-remarks-to-the-press-on-the-covid-response/

- 17.Bollyky TJ, Kickbusch I. Preparing democracies for pandemics. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pradelski B, Oliu-Barton M. In: Europe in the time of Covid-19. Bénassy-Quéré A, Weder di Mauro B, editors. CEPR Press; London: 2020. Green bridges: reconnecting Europe to avoid economic disaster; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.