Abstract

Mentalizing capacities depends on the quality of primary attachment interactions with caregivers who thinks of the child as a subject with mental states. Operationalized as reflective functioning, mentalization is crucial for regulating emotions and developing of a coherent sense of identity, for interacting with individuals making sense to own and others mental states, and for distinguishing internal and external realities without distortions. Although the clinical literature on interplay between mentalization, attachment, and emotional regulation is rich, the empirical research is limited. This study sought to explore connections between reflective functioning, attachment styles, and implicit emotion regulation, operationalized as defense mechanisms, in a group of depressive patients. Twenty-eight patients were interviewed using the adult attachment interview (AAI) and diagnosed using the Psychodynamic Chart-2 of the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, Second Edition. The reflective functioning scale and the defense mechanisms rating scale Qsort were applied to AAI transcriptions to assess reflective functioning and defensive profile. Patients with secure attachment showed significantly higher levels in reflective functioning and overall defensive functioning as compared to those with insecure attachment. Good reflective functioning and secure attachment correlated with mature defenses and specific defensive mechanisms that serve in better regulating affective states. Overall, the relationship between mentalization, attachment and emotion regulation lay the foundations for the delineation of defensive profiles associated with attachment patterns and reflective functioning in depressive patients. The systematic assessment of these psychological dimensions with gold-standard tools may help in tailoring personalized therapeutic interventions and promoting more effective treatments.

Key words: Mentalization, attachment, defense mechanisms, Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual-2, defense mechanisms rating scale Q-sort

Introduction

Mentalization can be defined as the individual’s imaginative capacity to understand and interpret-both implicit and explicitly-behavior in self and others as conjoined with intentional mental states, such as motives, affects, desires, beliefs, goals, and needs (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002). It allows to symbolize human experiences, enabling individuals to use thoughts and ideas to represent, describe and express their internal life, as well as deeply understand the intersubjective nature of social relationships (Bouchard et al., 2008). This form of representational mental activity is crucial for emotion regulation and development of a coherent sense of identity. Moreover, it helps in interacting with others making sense of what occurs in one’s own and others’ minds, in distinguishing between internal and external reality (e.g., cognitive and emotional processes), and in building connection with real-world (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016; Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Higgitt, & Target, 1994).

The construct of mentalization was founded within attachment theory and operationalized as reflective functioning (RF) (Fonagy, Target, Steele, & Steele, 1998). The individual develops mentalizing capacities in early infancy and their progression depends on the quality of primary attachment interactions with caregivers who thinks of the child as a subject with mental states (Bowlby, 1973). From this perspective, a close, warm, and affectively attuned infant-caregiver relationship allows the development of a secure attachment and provides the ideal condition for fostering an optimal mentalization. Conversely, caregivers’ failure in sensitiveness and responsiveness to the child’s need of protection and support may evolve into insecure attachment and hinder the development of mentalizing abilities (Fonagy et al., 2002).

Maladaptive caregiving of parents who cannot reflect empathically on the child’s inner experience and respond accordingly may promote severe distortions in child’s mentalizing ability, such as hypermentalization (e.g., overinterpretive mental state reasoning), vulnerability to mentalizing capacity breakdowns, and impairments in cohesive and integrated sense of self, adaptive capacities in affective regulation, and stable and mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships (Lingiardi & Bornstein, 2017; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2018).

Child-caregiver interactions are encoded and internalized by the child in ‘internal working models’ (IWM), which are mental representations of the attachment figure, the self, and their relationship that predict child’s later social and emotional outcome (Bowlby, 1969, 1980; Eagle, 2013; Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985).

Research has highlighted a strong connection between attachment and mentalization. Insecure attachment is related to RF deficits (Bouchard et al., 2008; Fonagy & Target, 1997, 1998; Nazzaro et al., 2017), which together increase the risk to develop several psychopathological conditions (e.g., anxiety and depressive disorders) and personality syndromes (e.g., Antonsen, Johansen, Ro, Kvarstein, & Wilberg, 2016; Bouchard et al., 2008; Calati, Oasi, De Ronchi, & Serretti, 2010; Fischer-Kern et al., 2010; Katznelson, 2014; Levy et al., 2006; Muller, Kaufhold, Overbeck, & Grabhorn, 2006; Taubner, White, Zimmermann, Fonagy, & Nolte, 2013). Moreover, parental RF appears to be involved in the intergenerational transmission of attachment (Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005; Stacks et al., 2014).

In light of what above described, the link between RF, attachment, and implicit emotion regulation seems rather clear. Emotion regulation strategies serve in mitigating distress through volunteer (explicit emotion regulation) or automatic (implicit emotion regulation) modification of the intensity, duration, and type of the experienced emotion (Gross & Thompson, 2007; Gyurak, Gross, & Etkin, 2011). Research demonstrated that both explicit and implicit emotion regulation strategies are essential for psychological well-being (Di Giuseppe, Ciacchini, Piarulli, Nepa, & Conversano, 2019; Gyurak et al., 2011), although the adequacy of implicit emotion regulation, such as mature defense mechanisms, plays a key role in the overall adaptiveness of individual psychological functioning (Di Giuseppe, Gennaro, Lingiardi, & Perry, 2019; Maffei et al., 1995).

Defense mechanisms are defined as unconscious mechanisms that mediate the individual’s reaction to emotional conflicts or external situations derived from difficulties in adapting inner needs, impulses, desires and thoughts to real world (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Perry, 2014). They serve to eliminate or attenuate negative sensations (distress, anxiety, insecurity, fear, etc.) connected to dangerous or threatening events or emotional experiences, real or imaginary (Olson, Perry, Janzen, Petraglia, & Presniak, 2011; Vaillant, 1992). According to the gold-standard classification of defense mechanisms (Di Giuseppe, Perry, Petraglia, Janzen, & Lingiardi, 2014; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Perry, 1990), each of the thirty defense mechanism holds specific definition and function that contribute to determine the individual defense style. Defense mechanisms are hierarchically organized into seven levels of adaptiveness, ranging from least to most mature (Table 1). At the more immature levels, defenses act a massive image distortions and withdrawn of charged feelings, while more adaptive defense levels allow higher awareness of feelings, ideas, thus maximize gratification and resilience (Di Giuseppe, Prout, Fabiani, & Kui, 2020). Immature defense mechanisms are often associated to various levels of severity of psychological functioning and different psychopathological conditions, especially personality disorders (e.g., Di Giuseppe, Gennaro et al., 2019; Hilsenroth, Callahan, & Eudell, 2003; Lingiardi et al., 1999; Oasi et al., 2017; Perry, Presniak, & Olson, 2013). On the other hand, mature defense mechanisms are associated with physical and psychological health and better adjustment (Hayden et al., 2021; Martino et al., 2020).

The relationship between attachment, defense mechanisms and psychological distress in clinical and nonclinical populations has been neglected in empirical research. In one study, Cramer and Kelly (2010) found that levels of insecure attachment style and defenses of denial were higher among parents abusing their children. Another research revealed that anxious attachment and immature defenses were significant predictors of postnatal depression (McMahon, Barnett, Kowalenko, & Tennant, 2005). Moreover, defense mechanisms may mediate the significant association between insecure attachment and alexithymic traits in youth population (Besharat & Khajavi, 2013). Consistent with this study, Laczkovics and colleagues (2018) supported the mediating role of immature defenses on the association between insecure attachment and psychopathology, suggesting that attachment had a direct impact on defense mechanisms, which in turn conveys the effects of insecure attachment on psychopathology. A recent research pointed out that insecure attachment is related to primitive defenses of denial, splitting, and projection (Prunas, Di Pierro, Huemer, & Tagini, 2019). Another study highlighted that secure attachment and adaptive defenses have a crucial impact in providing individuals exposed as children to intimate partner violence (IPV) with ways to survive their traumatic environments (Bain & Durbach, 2018).

According with these findings and clinical literature (cfr., Bowlby, 1973, 1980), we assume that attachment security is associated to mature psychological defenses intervening to modulate and reduce intense painful feelings and impact of negative experiences or events (Ciocca et al., 2020; Kobak & Bosmans, 2019; Malik, Wells, & Wittkowski, 2015). Similarly, it is reasonable to consider a strong connection between RF and defenses taking into account that they help in regulating emotional states activated within interpersonal relationships and influenced by mental procedures and representations from past meaningful relational experiences (Eagle, 2013). Moreover, consistent with the framework of the M Axis of the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, Second Edition (PDM-2) (Lingiardi & Bornstein, 2017), it is important to recognize that these capacities of mental functioning are interconnected and based on specific and integrated set of psychological processes (Lingiardi, McWilliams, Bornstein, Gazzillo, & Gordon, 2015).

Starting from these premises, the present study sought to explore the connections between all these relevant dimensions of psychological functioning in a group of depressive patients. More in detail, this research focused on two main aims:

Hypothesis 1: Identify whether attachment security was characterized by higher RF and higher overall defensive functioning (ODF) [see defense mechanisms rating scale Q-sort (DMRS-Q)’s description among ‘Measures’]. We hypothesized that people with secure attachment would show significantly higher RF and ODF as compared to insecure individuals.

Hypothesis 2: Investigate the associations between RF, attachment security/insecurity, and specific defense mechanisms. We hypothesized that high-adaptive defenses would be positively associated with both high RF and secure attachment, while disavowal, image-distorting defenses, and action defenses would be positively related to low RF and insecure attachment.

Methods

Participants’ sampling

The sample consisted of 28 patients recruited from two national counselling centers (Rome, Italy) between June 2019 and February 2020 (before the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic). The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) being at least 18 years old; ii) not having a diagnosis of organic syndrome, psychotic disorder or any syndrome with psychotic symptoms that could complicate the assessment of any variable in the study; and ii) not being on drug therapy. Clinicians (all of psychodynamic orientation) were direct to briefly describe to their patients the rationale of the research project on psychological assessment. All the patients indicated their willingness to participate in the study on a volunteer basis and without remuneration. They provided written informed consent. The patients were taken once-a-week psychotherapy treatment and therapists provided basic demographic and diagnostic data. The study protocol received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Sapienza University of Rome.

Table 1.

Defense levels and their corresponding defenses.

| Defense level | |

|---|---|

| Highly adaptive (mature) | Affiliation, altruism, anticipation, humor, self-assertion, self-observation, sublimation, suppression |

| Obsessional | Isolation of affect, intellectualization, undoing |

| Neurotic | Repression, dissociation, reaction formation, displacement |

| Minor image-distorting (narcissistic) | Devaluation (of self and others’ images), idealization (of self and others’ images), omnipotence |

| Disavowal | Denial, projection, rationalization, autistic fantasy |

| Major image-distorting (borderline) | Splitting (of self and others’ images), projective identification |

| Action | Acting out, help-rejecting complaining, passive aggression |

Patients

The clinical sample was equally distributed among gender. Mean age was approximately 45 years [standard deviation (SD)=4.90, range=39-58]. Twenty-three patients had a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) and five had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Moreover, according to the P Axis of the Psychodynamic Chart-2 (PDC-2) (see the description of the PDC-2 in section ‘Measures’) of the PDM-2, the level of patients’ personality organization was neurotic (mean score of overall personality organization=6.07, SD=1.72). Some patients (N=20) had a personality syndrome (comorbid with psychiatric diagnosis), which was distributed as follow: six depressive, four narcissistic, four borderline, two dependent, two obsessive, one anxious-avoidant and phobic, one hysteric-histrionic, while two patients showed subclinical depressive traits (rating score=3). Concerning the adult attachment interview (AAI) classifications distribution, the four-way distribution of states of mind with respect to attachment was as follows: 14 patients were Secure-Autonomous (F), 4 were Preoccupied (E) and 9 were Dismissing (Ds); the remaining 1 participant was Unresolved/ disorganized (U/d) with an additional classification as Dismissing. The length of treatment averaged 2.67 months (SD=0.88; range=1-4).

Measures

Clinical questionnaire

We constructed an ad hoc clinician report questionnaire to obtain information about therapists, patients, and their psychotherapies. Clinicians provided basic demographic and professional data, as well as DSM-5 diagnoses assigned at the intake. Clinicians also furnished data on the therapies, such as length of treatment.

Psychodynamic Chart-2 of the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual

The PDC-2 (Gordon & Bornstein, 2015) is a clinician report tool used to guide clinicians in the PDM-2-oriented diagnostic assessment of adults. The PDC-2 starts with Section I: Level of Personality Organization calls for ratings of identity, object relations, level of defenses, and reality testing. Then, the clinician has to provide an overall rating of the personality organization as either ‘normal’ (healthy), mildly dysfunctional (neurotic), dysfunctional (borderline), or severely dysfunctional (psychotic). Section II: Personality Styles/Syndromes (P Axis) asks the clinician to determine the patient’s emerging personality patterns by checking as many relevant patterns as apply; then, the clinician notes the one or two most dominant patterns. For research purposes, each pattern can be given a rating from 1 (severe) to 5 (high functioning). Section III: Mental Functioning (M Axis), which asks the clinician to rate the patient’s level of strength or weakness on each of 12 mental functions on a scale from 1 (severe deficits) to 5 (healthy) and then to provide an overall rating for level of personality severity as the sum of these 12 ratings. Section IV: Symptom Patterns (S Axis) asks the practitioner to describe the patient’s main symptom patterns from those that are related to predominantly psychotic disorders, mood disorders, disorders primarily related to anxiety, event- and stressor-related disorders, and so forth. Moreover, the clinician may use DSM or ICD symptoms and codes here. The dominant symptoms are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (severe) to 5 (mild). Section V: Cultural, Contextual, and Other Relevant Considerations. In the present study, we used only the first two sections of this measure on the personality assessment.

Adult attachment interview

The adult attachment interview (AAI) (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996) is a semi-structured interview used to assesses the individual’s ‘state of mind’ with respect to attachment relationships. The AAI consists of 20 questions asked in a set order with standardized probes. Individuals are asked to describe the overall quality of their childhood relationship with their parents as well as any experiences of loss, rejection, early separation, and maltreatment. The interview requires participants to reflect on their parents’ styles of parenting and to consider how their childhood experiences with their parents may have influenced their personality development. The traditional AAI scoring system points to the following attachment classification: secure/autonomous (F), dismissing (Ds), enmeshed/preoccupied (E), or unresolved/disorganized (U/d). The U/d category is assigned a secondary organized classification (F, Ds or E). Previous research has shown that the AAI has remarkable stability and predictive validity (for a review, see Hesse, 2008). Individuals classified as F are able to cope effectively with negative feelings about past experiences and are aware of the value of attachment relationships. On the other hand, E individuals are overwhelmed by anxiety and negative emotions arising from childhood memories. Ds individuals deal with painful feelings related to attachment relationships through ‘defensive exclusion’ (Bowlby, 1973) of attachment-related memories, idealization of painful relationships or derogation of attachment figures. Individuals with U category show disorganization or confusion with regard to attachment-related loss or trauma.

Reflective functioning scale

The reflective functioning scale (RFS) (Fonagy et al., 1998) is a quantified index of mentalization capacity applied to the transcripts of the AAI (George et al., 1996). It is designed to assess whether subjects are able to understand attachment- related experiences in terms of mental states. The coding system is based on the following dimensions: i) awareness of the nature of mental states (e.g., the fact that mental states can be disguised); ii) explicit effort made to tease out the mental states underlying one’s own and others’ behavior (e.g., an awareness that different people may experience different feelings and thoughts in response to the same situation); iii) recognition of the developmental aspects of mental states (e.g., an understanding of age-derived changes in mental states); and iv) recognition of mental states in the interviewer (e.g., guessing that an interviewer may be distressed while listening to an emotionally difficult story). RF is assessed through ratings of the perceived level of reflection made by the individual on the different passages in the AAI, with questions that directly encourage the subject to employ reflective capacities (‘demand,’ as opposed to ‘permit,’ questions) carrying more weight. The scores given to subject’s statements throughout the interview are weighed together to obtain a final RF score on an 11- point scale ranging from –1 (negative reflective capacity or antireflective) to 5 (ordinary reflective capacity) to 9 (exceptionally reflective functioning). The RFS was validated on the coherence scale of the AAI and shows good interrater reliability when administered by trained raters (Fonagy et al., 1998). Psychometric analysis confirmed the one-factor structure, which also showed good reliability and stability over time (Taubner et al., 2013).

Defense mechanisms rating scale-Q sort

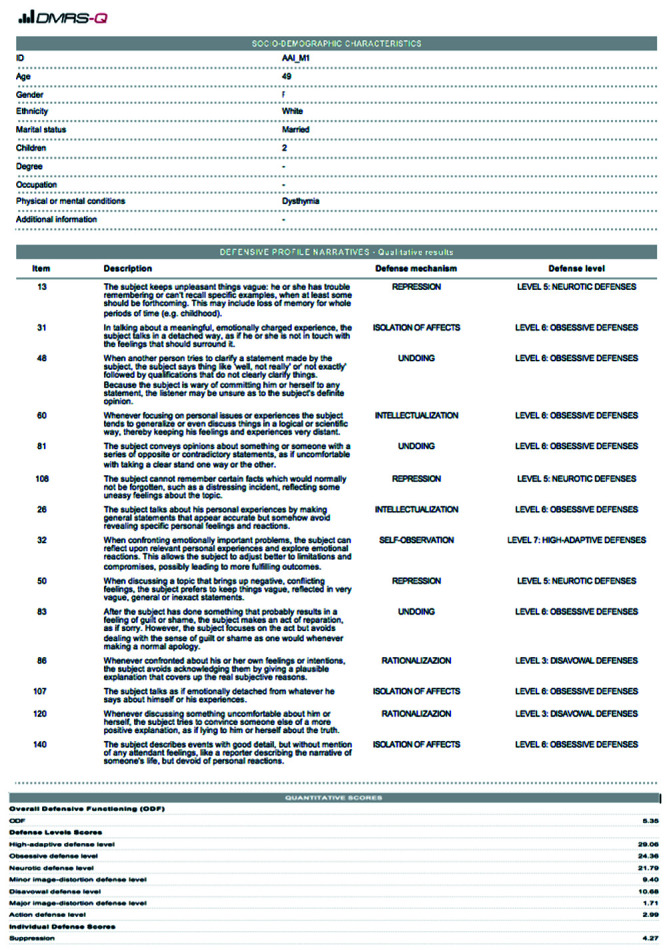

The DMRS-Q (Di Giuseppe et al., 2014) is a computerbased observer-rated measure developed for the assessment of defense mechanisms in clinical setting and based on the gold-standard theory of defense mechanisms (Perry, 1990). The DMRS-Q consists of 150 statements describing 30 defense mechanisms in terms of personal mental states, relational dynamics, verbal and nonverbal expressions, self and others’ perceptions that emerge on occasions when the subject experiences internal or external stress or conflict. Raters sorted each statement utilizing a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from least characteristic to most characteristic, which described how each defense pattern contributed to the individual’s defensive functioning. After sorting all 150 statements into a seven-ranks forced distribution, the software provides a DMRS-Q report (Figure 1) with: i) a qualitative description of the patient defensive profile, the so called defensive profile narratives (DPN); and ii) quantitative scores for the ODF, seven hierarchically ordered defense levels, and 30 defense mechanisms (see Table 1 for a comprehensive description of the hierarchy of defense mechanisms). The DMRS-Q rating procedure is available online at: https://webapp.dmrs-q.com/login

Procedure

All patients were assessed with the DSM-5 and PDC-2 of the PDM-2 after 4 initial diagnostic interviews to collect background information, developmental history, and current concerns. In this time, they interviewed with the AAI by two member of the research group. AAI interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and was coded by two certified AAI coders who were blind to all other study variables. The interrater reliabilities (ICC) of the AAI subscales were of 0.73 and agreement of the two raters on major attachment classification (four-way classification) was 85.7% (with 100% agreement on insecure vs secure classification). RF was coded according to the RFS from verbatim transcripts of the AAI by two raters who performed the training trained by H. Steele. The ICC of RF raters was 0.84. Defense mechanisms were assessed from AAI transcripts by two raters trained in the use of the DMRS-Q. Raters’ ICC among all DMRS-Q scales was 0.82 on average.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to verify differences in RF and ODF between patients with secure attachment versus patients with insecure attachment. Bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r, two-tailed) were carried out to examine the relationship between RF, attachment, and defense mechanisms. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 23 for Windows.

Results

Differences between groups with secure versus insecure attachment in reflective functioning and overall defensive functioning

Differences in mentalization (as assessed using the RFS) and defensive functioning (as assessed using the ODF index of DMRS-Q) between patients with secure (N=15) versus insecure/disorganized (N=13) attachment were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. Results showed significant differences between groups in RF (Mann-Whitney U=3.50; P≤0.000, two tailed) and ODF (Mann-Whitney U=45, P=0.016, two tailed). More in detail, levels of RF and ODF were greater for secure patients (MdnRF=5; MdnODF=5.31) than for insecure/disorganized patients (MdnRF=3; MdnODF=4.73).

Relationships among mentalization, attachment and defense mechanisms

Table 2 displays correlations between RF, attachment, and defensive functioning assessed among the whole hierarchy of defense mechanisms.

Results showed that RF was positively associated with the high-adaptive defense level, and negatively associated with minor image distorting, major image distorting, and acting defense levels. Moreover, RF showed positive correlations with the individual defenses suppression, self-observation, affiliation, and undoing, and negative correlations with the individual defenses omnipotence, projection, splitting of self-image, help-rejecting complaining, and acting out. Consistently, attachment security was positively associate with the high-adaptive defensive level and with the individual defenses affiliation and undoing. Secure attachment also showed negative correlations with the individual defenses displacement, projection, splitting od self-image, and acting out.

Figure 1.

Example of a shortened defense mechanism rating scale-Q (DMRS-Q) report.

Discussion

Empirical research advances have been providing deeper understanding of connections between psychodynamic constructs helped by the development of more and more effective instruments for their assessment. Applying gold-standard tools for testing attachment patterns (AAI), RF (RFS) and defense mechanisms (DMRS-Q), this pilot study demonstrated the relationship between these psychological constructs in a sample of dysthymic individuals. Taking into account the whole hierarchy of defense mechanisms, our findings lay the foundations for the delineation of defensive profiles associated with specific attachment patterns and RF capacities.

Table 2.

Associations among reflective functioning, attachment security/insecurity, defensive levels and mechanisms.

| DMRS-Q | RF | Secure/insecure attachment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defense levels | High-adaptive | 0.471* | 0.410* |

| Obsessional | 0.170 | 0.101 | |

| Neurotic | 0.042 | –0.195 | |

| Minor-image distorting | –0.419* | –0.305 | |

| Disavowal | –0.353 | –0.287 | |

| Major-image distorting | –0.408* | –0.219 | |

| Action | –0.518** | –0.339 | |

| Defense mechanisms | Suppression | 0.379* | 0.331 |

| Sublimation | 0.195 | 0.192 | |

| Self-observation | 0.364 | 0.284 | |

| Self-assertion | 0.417* | 0.233 | |

| Humor | 0.218 | 0.147 | |

| Anticipation | 0.242 | 0.330 | |

| Altruism | 0.201 | 0.120 | |

| Affiliation | 0.433* | 0.538** | |

| Isolation of affects | –0.188 | 0.076 | |

| Intellectualization | –0.091 | –0.087 | |

| Undoing | 0.449* | 0.379* | |

| Repression | 0.245 | –0.093 | |

| Dissociation | –0.305 | –0.257 | |

| Reaction Formation | 0.295 | 0.328 | |

| Displacement | –0.307 | –0.410* | |

| Devaluation of self-image | –0.278 | –0.336 | |

| Devaluation of others’ image | –0.306 | –0.302 | |

| Idealization of self-image | –0.268 | –0.149 | |

| Idealization of others’ image | –0.252 | 0.323 | |

| Omnipotence | –0.444* | –0.317 | |

| Denial | –0.170 | –0.211 | |

| Rationalization | –0.160 | –0.055 | |

| Projection | 0.595*** | –0.525** | |

| Autistic fantasy | –0.127 | –0.039 | |

| Splitting of self-image | 0.643*** | –0.518** | |

| Splitting of others’ image | –0.076 | –0.077 | |

| Projective identification | –0.304 | –0.135 | |

| Passive aggression | –0.262 | –0.142 | |

| Help-rejecting complaining | –0.498** | –0.331 | |

| Acting out | –0.559** | –0.396* |

DMRS-Q, defense mechanism rating scale-Q sort; RF, reflective functioning. Attachment (secure coded=1, insecure/disorganized coded=0); *P≤0.05; ** P≤0.01; ***P≤0.001.

Our first hypothesis, that people with secure attachment would show significantly higher RF and more adaptive defensive functioning than insecure individuals, was fully confirmed by the findings. Consistent with literature and empirical contributions in the field (Besharat & Khajavi, 2013; Boldrini, Lo Buglio, Giovanardi, Lingiardi, & Salcuni, 2020; Malik et al., 2015; Bouchard et al., 2008; Fonagy & Target, 1997, 1998; Horz-Sagstetter, Mertens, Isphording, Buchheim, & Taubner, 2015; Nazzaro et al., 2017), the results indicate the shared line of development of two very important aspects of psychological functioning, such as mentalization and emotion regulation, that take place in early relationships with sensitive and responsive caregivers as main sources of the development of secure internal working models of attachment (Bowlby, 1969; Carrere & Bowie, 2012; Fonagy &Target, 1998; Hershenberg et al., 2011). Conversely, we confirmed Besharat and Khajavi’s idea (2013) that massive use of immature defense mechanisms in insecure attachment may be aimed to react against mental distress by blocking awareness of negative emotions.

At a deeper level of inquiry, the results fully confirmed our second hypothesis of a positive association between RF, secure attachment and adaptive defense mechanisms. This research found the use of mature defense mechanisms in people with secure attachment and good RF, such as affiliation and undoing. Looking at the functions of these defenses, we notice that affiliation enhances personal coping skills and attachment needs satisfaction by seeking support from others, while undoing minimizes the distress caused by uncomfortable feelings by expressing a series of opposite affects, impulses, or actions (e.g., misdeeds followed by acts of reparation) in order to camouflage the subject’s primary feeling or intention (Perry, 1990).

Conversely, the use of immature-depressive defenses, in particular projection, splitting of self-image, and acting out, were strongly related to poor RF and insecure attachment. These defensive mechanisms protect the individual from awareness of internal conflict and external stressors by attributing his or her own unacknowledged feelings, impulses, or thought to others (projection), by failing to integrate the positive and negative qualities of the self into cohesive image (splitting of self-image), and by expressing of intolerable feelings in impulsive behaviors without prior thought (acting out). These findings add empirical evidences to previously reported correlation between secure/ insecure attachment and mature/primitive defense mechanisms (Besharat & Khajavi, 2013; Ciocca et al., 2020; Cramer & Kelly, 2010; Kobak & Bosmans, 2019; McMahon et al., 2005; Prunas et al., 2019).

In addition, our results showed that good levels of RF was associated with higher use of self-observation, self-assertion, and suppression, which are all mature defenses that helps the individual in dealing with internal conflicts or external stressors by recurring to introspective thinking, direct expression or feelings and ideas, or voluntarily temporarily avoiding thinking about disturbing problems, in order to maximize gratification and adjustment. In particular, selfobservation allows the person to make optimal adaptation to the demands of external reality based on having an accurate view of one’s own affects, wishes and impulses, and behavior. Moreover, we found that RF was negatively associated to image-distorting and action defense levels and to as individual defenses of omnipotence and help-rejecting complaining, supporting the relevant interplay between mentalization and emotion regulation. These results suggest that the capacity to understand and interpret self and others’ behaviors as conjoined with intentional mental states (Fonagy et al., 2002) is strongly related to the ability to deal with one’s feelings, desires, and thoughts without recurring to self and others’ images distortion and impulsive withdrawn of intolerable feelings.

Taking together these findings, the primacy of interpersonal dimension and the relationship between attachment, RF and defense mechanisms become more evident. Attachment theory (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Bowlby, 1973; Collins & Read, 1990; Mikulincer, 1995) often linked attachment security to positive perceptions of the self and others, and insecure attachment patterns to low self-esteem and negative expectations about the others. In our sample the security of attachment and good mentalization skills were related to mature defenses that frame a safe and balanced relationship with the self (selfassertion and self-observation), but also indicate the capacity to acknowledge the trustfulness of the other and the possibility to rely on others as a resource (affiliation).

The present study also presented some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and therefore generalization must be drawn with caution. Further research involving larger stratified samples should be pursued to confirm these associations. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of the research, only exploratory analyses of associations between the studied variables were possible. Longitudinal studies should be designed to gain insight on how defense mechanisms, attachment patterns and RF might impact the adjustment of dysthymic patients during and after psychological interventions. Finally, RF and defensive mechanisms were evaluated using the same source of the attachment assessment (the AAI transcripts). Further studies should use mixed method (i.e., interviews and self-reports) to have a broader assessment of these variables.

However, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to have studied the association between defenses and mentalizing capacity (assessed with gold-standard tools), taking into account the link with the attachment. Our findings are consistent with the diagnostic framework of the PDM-2 and have significant implications from both the theoretical and clinical perspectives (Hilsenroth, Katz, & Tanzilli, 2018).

The strong relationship between two largely, but separately, studied constructs as mentalization and emotion regulation suggests new directions for bridging these fields of study, for example by conceptualizing mentalizing ability as peculiar high-adaptive defensive patterns (i.e. affiliation, self-observation and self-assertion). Furthermore, the importance of a broad assessment of these constructs highlights the need of developing tailored interventions for depressed patients, informed by the use of specific defense mechanisms and their relations with insecure attachment and mentalization deficits.

In particular, psychological interventions aimed at preventing and addressing depressive problems should focus on the interrelation between attachment insecurity, low RF and the use of immature-depressive defenses. Thus, it might be useful to first establish with patients a secure and trustful relationship (Fonagy, Luyten, Allison, & Campbell, 2019) in which tackling the difficulties related to insecure internal working models of attachment (e.g. lack of trust in others, problems in emotion regulation, low levels of self-esteem; see Bowlby, 1973), at the same time encouraging the patients to open up and value their resources, empowering the self-image and providing a positive relationship in which to improve the relationship with the other.

Additionally, within a good therapeutic relationship (informed on these psychological dimensions) patients can increase their mentalizing abilities and learn to better symbolize their psychic contents, moving out from the immature defensive dimensions of acting-out and helpreject complaining to a more mature capacity for self-observation and expression of one’s suffering (Hoglend & Perry, 1998; Conversano & Di Giuseppe, 2021).

As suggested by previous studies (e.g., Kobak & Bosmans, 2019; Mikulincer & Horesh, 1999), this research supports that the joint effect of high RF, secure attachment, and mature defense mechanisms may help stabilizing the mental health of patients, helping them regulating better their emotions and developing positive representations of the self and the others.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks Anna Canale for her support and encouragement in the preparation of this work.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen B. T., Johansen M. S., Ro F. G., Kvarstein E. H., Wilberg T. (2016). Is reflective functioning associated with clinical symptoms and long-term course in patients with personality disorders?. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 64, 46-58. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K., Horowitz L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med:psych/97801996 80375.001.0001 [Google Scholar]

- Besharat M. A., Khajavi Z. (2013). The relationship between attachment styles and alexithymia: mediating role of defense mechanisms. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(6), 571-576. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini T., Lo Buglio G., Giovanardi G., Lingiardi V., Salcuni S. (2020). Defense mechanisms in adolescents at high risk of developing psychosis: An empirical investigation. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 23(1). doi:10.4081/ripppo.2020.456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard M., Target M., Lecours S., Fonagy P., Tremblay L., Schachter A., Stein H. (2008). Mentalization in adult attachment narratives: reflective functioning, mental states, and affect elaboration compared. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 25(1), 47-66. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.25.1.47. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: vol. I. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1973). Attachment and loss: vol. II Separation, anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1980). Attachment and Loss. Vol. 3: Loss, Sadness and Depression. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Calati R., Oasi O., De Ronchi D., Serretti A. (2010). The use of the defense style questionnaire in major depressive and panic disorders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 83, 1-13. doi:10.1348/147608309X 464206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrere S., Bowie B. H. (2012). Like parent, like child: Parent and child emotion dysregulation. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(3), e23-e30. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocca G., Rossi R., Collazzoni A., Gorea F., Vallaj B., Stratta P., Longo L., Limoncin E., Mollaioli D., Gibertoni D., Santarnecchi E., Pacitti F., Niolu C., Siracusano A., Jannini E. A., Di Lorenzo G. (2020). The impact of attachment styles and defense mechanisms on psychological distress in a nonclinical young adult sample: A path analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 384-390. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020. 05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N. L., Read S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644-663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conversano C., Di Giuseppe M. (2021). Psychological factors as determinants of chronic conditions: Clinical and psychodynamic advances. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 635708. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P., Kelly F. D. (2010). Attachment style and defense mechanisms in parents who abuse their children. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(9), 619-627. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef3ee1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Ciacchini. R., Piarulli A., Nepa G., Conversano C. (2019). Mindfulness disposition and defense style as positive responses to psychology distress in oncology professionals. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 40, 104-110. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Gennaro A., Lingiardi V., Perry J.C. (2019). The role of defense mechanisms in emerging personality disorders in clinical adolescents. Psychiatry, 82, 128-142. doi:10.1080/00332747.2019.1579595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Lucchesi M., Michelini M., Vitiello S., Piantanida A., Fabiani M., Maffei S., Conversano C. (2020). Preliminary reliability and validity of the DMRS-SR-30, a novel self-report based on the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 870. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J.C., Petraglia J., Janzen J., Lingiardi V. (2014). Development of a Q-sort version of the defense mechanisms rating scales (DMRS-Q) for clinical use. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 452-465. doi:10.1002/jclp.22089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Prout T. A., Fabiani M., Kui T. (2020). Defensive profile of parents of children with externalizing problems receiving Regulation-Focused Psychotherapy for Children (RFP-C): A pilot study. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8(2). doi:10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp-2515. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle M. N. (2013). Intersections: Psychoanalysis and psychological science.Attachment and psychoanalysis: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Kern M., Buchheim A., Horz S., Schuster P., Doering S., Kapusta N. D., Taubner S., Tmej A., Rentrop M., Buchheim P., Fonagy P. (2010). The relationship between personality organization, reflective functioning, and psychiatric classification in borderline personality disorder. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(4), 395-409. doi:10.1037/a0020862 [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Target M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: their role in self-organization. Development and psychopathology, 9(4), 679-700. doi:10.1017/s095457949700 1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Gergely G., Jurist E., Target M. (2002). Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self. Other Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Luyten P., Allison E., Campbell C. (2019). Mentalizing, epistemic trust and the phenomenology of psychotherapy. Psychopathology, 52(2), 94-103. doi:10.1159/ 000501526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Steele H., Steele M. (1991). Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment at one year of age. Child Development, 62(5), 891-905. doi:10.2307/1131141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Steele M., Steele H., Higgitt A., Target M. (1994). The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1992. The theory and practice of resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 35(2), 231-257. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Target M. (1998). Mentalization and the changing aims of child psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 8(1), 87-114. doi:10.1080/ 10481889809539235. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Target M., Steele H., Steele M. (1998). Reflective- functioning manual: version 5 for application to adult attachment interviews. (Unpublished manual) University College London. [Google Scholar]

- George C., Kaplan N., Main M. (1996). Adult Attachment Interview (3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkley. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R. M., Bornstein R. F. (2015). Brief manual for the Psychodiagnostic Chart-2 (PDC-2). Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/14475535/Brief_Manual_for_the_Psychodiagnostic_Chart-2_PDC-_ [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J., Thompson R. A. (2007). Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations. Gross J. J. (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation (pp. 3-24). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A., Gross J. J., Etkin A. (2011). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a dual-process framework. Cognition & Emotion, 25(3), 400-412. doi:10.1080/02699931.2010.544160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. C., Mullauer P. K., Beyer K. J., Gaugeler R., Senft B., Dehoust M. C., Adreas S. (2021). Increasing mentalization to reduce maladaptive defense in patients with mental disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 637915. doi:10.3389/ fpsyt.2021.637915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershenberg R., Davila J., Yoneda A., Starr L. R., Miller M. R., Stroud C. B., Feinstein B. A. (2011). What I like about you: The association between adolescent attachment security and emotional behavior in a relationship promoting context. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 1017-1024. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. (2008). The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 552-598). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenroth M. J., Callahan K. L., Eudell E. M. (2003). Further reliability, convergent and discriminant validity of overall defensive functioning. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(11), 730-737. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000095125.92493.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenroth M. J., Katz M., Tanzilli A. (2018). Psychotherapy research and the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM- 2). Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(3), 320-327. doi:10.1037/ pap0000207 [Google Scholar]

- Hoglend P., Perry J. C. (1998). Defensive functioning predicts improvement in treated major depressive episodes. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186(4), 238-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horz-Sagstetter S., Mertens W., Isphording S., Buchheim A., Taubner S. (2015). Changes in reflective functioning during psychoanalytic psychotherapies. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 63(3), 481-509. doi:10.1177/0003065115591977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katznelson H. (2014). Reflective functioning: a review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(2), 107-117. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R., Bosmans G. (2019). Attachment and psychopathology: a dynamic model of the insecure cycle. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 76-80. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laczkovics C., Fonzo G., Bendixsen B., Shpigel E., Lee I., Skala K., Prunas A., Gross J., Steiner A., Huemer J. (2018). Defense mechanism is predicted by attachment and mediates the maladaptive influence of insecure attachment on adolescent mental health. Current Psychology 39, 1388-1396. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9839-1. [Google Scholar]

- Levy K. N., Meehan K. B., Kelly K. M., Reynoso J. S., Weber M., Clarkin J. F., Kernberg O. F. (2006). Change in attachment patterns and reflective function in a randomized control trial of transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1027-1040. doi:10.1037/0022-006X. 74.6.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Bornstein R. F. (2017). Profile of mental functioning - M axis. Lingiardi V., McWilliams N. (Eds.), Psychodynamic diagnostic manual (2nd ed.). (pp. 75-133). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Lonati C., Delucchi F., Fossati A., Vanzulli L., Maffei C. (1999). Defense mechanisms and personality disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(4), 224-228. doi:10.1097/00005053-199904000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., McWilliams N., Bornstein R. F., Gazzillo F., Gordon R. M. (2015). The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Version 2 (PDM-2): Assessing patients for improved clinical practice and research. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32(1), 94-115. doi:10.1037/a0038546 [Google Scholar]

- Maffei C., Fossati A., Lingiardi V., Madeddu F., Borellini C., Petrachi M. (1995). Personality maladjustment, defenses, and psychopathological symptoms in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Personality Disorders, 9(4), 330-345. doi:10.1521/pedi.1995.9.4.330 [Google Scholar]

- Main M., Kaplan N., Cassidy J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66-104. doi:10.2307/3333827 [Google Scholar]

- Malik S., Wells A., Wittkowski A. (2015). Emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between attachment and depressive symptomatology: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 428-444. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014. 10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino G., Caputo A., Schwarz P., Bellone F., Fries W., Quattropani M. C., Vicario C. M. (2020). Alexithymia and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1763. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C., Barnett B., Kowalenko N., Tennant C. (2005). Psychological factors associated with persistent postnatal depression: past and current relationships, defense styles and the mediating role of insecure attachment style. Journal of Affective Disorders, 84(1), 15-24. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. (1995). Attachment style and the mental representation of the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1203-1215. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1203 [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Horesh N. (1999). Adult attachment style and the perception of others: The role of projective mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76, 1022-1034. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P.R. (2018). Attachment theory as a framework for studying relationship dynamics and functioning. Vangelisti A. L., Perlman D. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (p. 175-185). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316417867.015 [Google Scholar]

- Muller C., Kaufhold J., Overbeck G., Grabhorn R. (2006). The importance of reflective functioning to the diagnosis of psychic structure. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 79, 485-494. doi:10.1348/147608305x68048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro M.P., Boldrini T., Tanzilli A., Muzi L., Giovanardi G., Lingiardi V. (2017). Does reflective functioning mediate the relationship between attachment and personality?. Psychiatry Research, 256, 169-175. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017. 06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oasi O., Buonarrivo L., Codazzi A., Passalacqua M., Risso RicciG. M., Straccamore F., Bezzi R. (2017). Assessing personality change with Blatt’s anaclitic and introjective configurations and Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure profiles: Two case studies in psychodynamic treatment. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 20(1). doi:10.4081/ripppo.2017.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson T. R., Perry J. C., Janzen J. I., Petraglia J., Presniak M. D. (2011). Addressing and interpreting defense mechanisms in psychotherapy: General considerations. Psychiatry, 74(2), 142-165. doi:10.1521/psyc.2011.74.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (1990). Defense mechanism rating scales (5th ed.). Boston, MA: The Cambridge Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J.C. (2014). Anomalies and specific functions in the clinical identification of defense mechanisms, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 406-418. doi:10.1002/jclp.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J.C., Presniak M.D., Olson T.R. (2013). Defense mechanisms in schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders. Psychiatry, 76(1), 32-52. doi:10.1521/psyc.2013.76.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunas A., Di Pierro R., Huemer J, Tagini A. (2019). Defense mechanisms, remembered parental caregiving, and adult attachment style. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36, 64-72. doi:10.1037/pap0000158 [Google Scholar]

- Slade A., Grienenberger J., Bernbach E., Levy D., Locker A. (2005). Maternal reflective functioning, attachment, and the transmission gap: A preliminary study. Attachment and Human Development, 7(3), 283-298. doi:10.1080/14616730 500245880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacks A. M., Muzik M., Wong K., Beeghly M., Huth-Bocks A., Irwin J. L., Rosenblum K. L. (2014). Maternal reflective functioning among mothers with childhood mal- treatment histories: links to sensitive parenting and infant attachment security. Attachment and Human Development, 16(5), 515-533. doi:10.1080/14616734.2014. 935452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubner S., Hörz S., Fischer-Kern M., Doering S., Buchheim A., Zimmermann J. (2013). Internal structure of the Reflective Functioning Scale. Psychological Assessment. 25(1), 127-135. doi:10.1037/a0029138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubner S., White L. O., Zimmermann J., Fonagy P., Nolte T. (2013). Attachment-related mentalization moderates the relationship between psychopathic traits and proactive aggression in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 929-938. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9736-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1992). Ego mechanisms of defense: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Washington: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]