Abstract

Objective.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a condition characterized by bony proliferation at sites of tendinous and ligamentous insertions in the spine. Spinal mobility is reduced in DISH and may affect movement in the thorax, potentially leading to restrictive pulmonary function. This study investigated whether DISH is associated with restrictive spirometric pattern (RSP) in former and current smokers.

Methods.

Participants (n = 1784) with complete postbronchodilator spirometry who did not meet spirometric criteria for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at time of enrollment in the COPDGene study were included in this study. Subjects were classified as RSP if they had forced expiratory volume in 1 s(FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio > 0.7 with an FVC < 80%. Computed tomography (CT) scans were scored for the presence of DISH in accordance with the Resnick criteria. Chest CT measures of interstitial and alveolar lung disease, clinical symptoms, health surveys, and 6-min walking distance were recorded. Uni- and multivariable analyses were performed to test the association of DISH with RSP.

Results.

DISH was present in 236 subjects (13.2%). RSP was twice as common in participants with DISH (n = 90/236, 38.1%) compared to those without DISH (n = 301/1548, 19.4%; p < 0.001). In multivariable analysis, DISH was significantly associated with RSP (OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.22–2.60; p = 0.003) after adjusting for potential confounders. The RSP group with and without DISH had significantly worse spirometry, dyspnea, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, BODE index (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity), and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 questionnaire score.

Conclusion.

In heavy smokers with an FEV1/FVC ratio > 0.70, DISH is associated with RSP after adjustment for intrinsic and extrinsic causes of restrictive lung function. (Clinical trial registration number: NCT00608764.)

Key Indexing Terms: DIFFUSE IDIOPATHIC SKELETAL HYPEROSTOSIS, COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY, SPIROMETRY, LUNG FUNCTION

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a common condition characterized by bony proliferation at sites of tendinous and ligamentous insertion of the spine. On imaging, it is typically characterized by flowing ossification in the area of the anterior longitudinal ligament, most commonly in the thoracic and lumbar spine and in some cases may be associated with extraspinal enthesopathies1. DISH is a disease of aging with increasing prevalence with advancing age especially prominent in the sixth to seventh decade. The estimated prevalence is around 10% with a male predominance2. The condition is commonly identified as an incidental finding when imaging is performed for other reasons3. However, spinal stiffness and decreased mobility are described as possible symptoms. The etiology of DISH is still unknown, but it is associated with diabetes mellitus type II and obesity4. The bridging osseous tissue between vertebral bodies in DISH creates a stiff “thoracic cage” that may affect ventilation5. More recently it has been shown that DISH is associated with lower lung volumes [lung capacity as measured by computed tomography (CT)]6. A limitation of that study was that for the functional assessment only prebronchodilator spirometric data was obtained. Further, kyphotic angle, which may be associated with pulmonary restriction, was not available in that cohort.

Restrictive spirometric pattern (RSP) in general population studies can be explained by intrinsic or extrinsic restrictive factors. The intrinsic group of factors can be divided into interstitial, pleural, and alveolar disease processes. Known extrinsic factors are obesity, abdominal ascites, neuromuscular diseases, and kyphoscoliosis7. While measurement of lung volumes is required to define a true restriction, in 1991 the American Thoracic Society suggested that a restrictive ventilatory defect defined as abnormally low forced vital capacity (FVC) in combination with a normal or high forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/FVC ratio could be termed a “restrictive pattern”8. The COPDGene study is a multicenter observational study designed to identify genetic factors associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Previous work in the COPDGene study has shown that many heavy smokers with normal FEV1/FVC ratio and reduced FEV1 (< 80% predicted) can be classified as PRISm, a category distinct from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification for COPD that also has characteristics suggestive of restriction and is distinct from RSP9,10. The PRISm group of smokers had increased prevalence of diabetes, central obesity, greater mortality, more respiratory symptoms, less emphysema, and more airway wall thickening compared with normal spirometry and FEV1 > 80%. Based on these definitions, RSP is a subset of both “normal” spirometry and PRISm groups. COPDGene is a unique cohort in that it included subjects with a heavy smoking history and excluded subjects with previously diagnosed interstitial lung disease (ILD) or significant ILD identified on chest CT. The selection bias in the design of the COPDGene cohort suggests that many subjects in this cohort will be dominated by risk for COPD progression rather than classic “restriction.”

We hypothesized that DISH in heavy smokers with no known ILD would have a higher incidence in subjects with RSP compared to those with “normal” physiology and that this association would be independent of known other factors for restriction. Our aim was to investigate the relationship between DISH and RSP in current and former smokers with an FEV1/FVC ratio > 0.70 who were participating in the COPDGene study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

All subjects in this report were participants in the COPDGene study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT000608764) and enrollment and exclusion criteria have been previously described11. The COPDGene study was initiated in 2007–2011, enrolling 10,192 smokers with a minimum of 10 pack-years of smoking and 108 never smokers (non-Hispanic white and African American), with the goal to define subtypes of smoking-related lung disease and genetic associations to those subtypes. Chest CT scans were performed and extensive clinical data have been obtained. All subjects provided written informed consent, and the study was approved at each of the 21 clinical centers (see Supplementary Data for list of centers, available with the online version of this article). This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board approval for COPDGene is HS-2778, “COPDGene Central Data Management, Imaging and Human Subject Contacts.”

COPDGene specifically excluded those with a diagnosis of ILD and other lung diseases (except a history of asthma), and excluded subjects without a diagnosis of ILD whose CT scans on radiology review showed significant history of ILD.

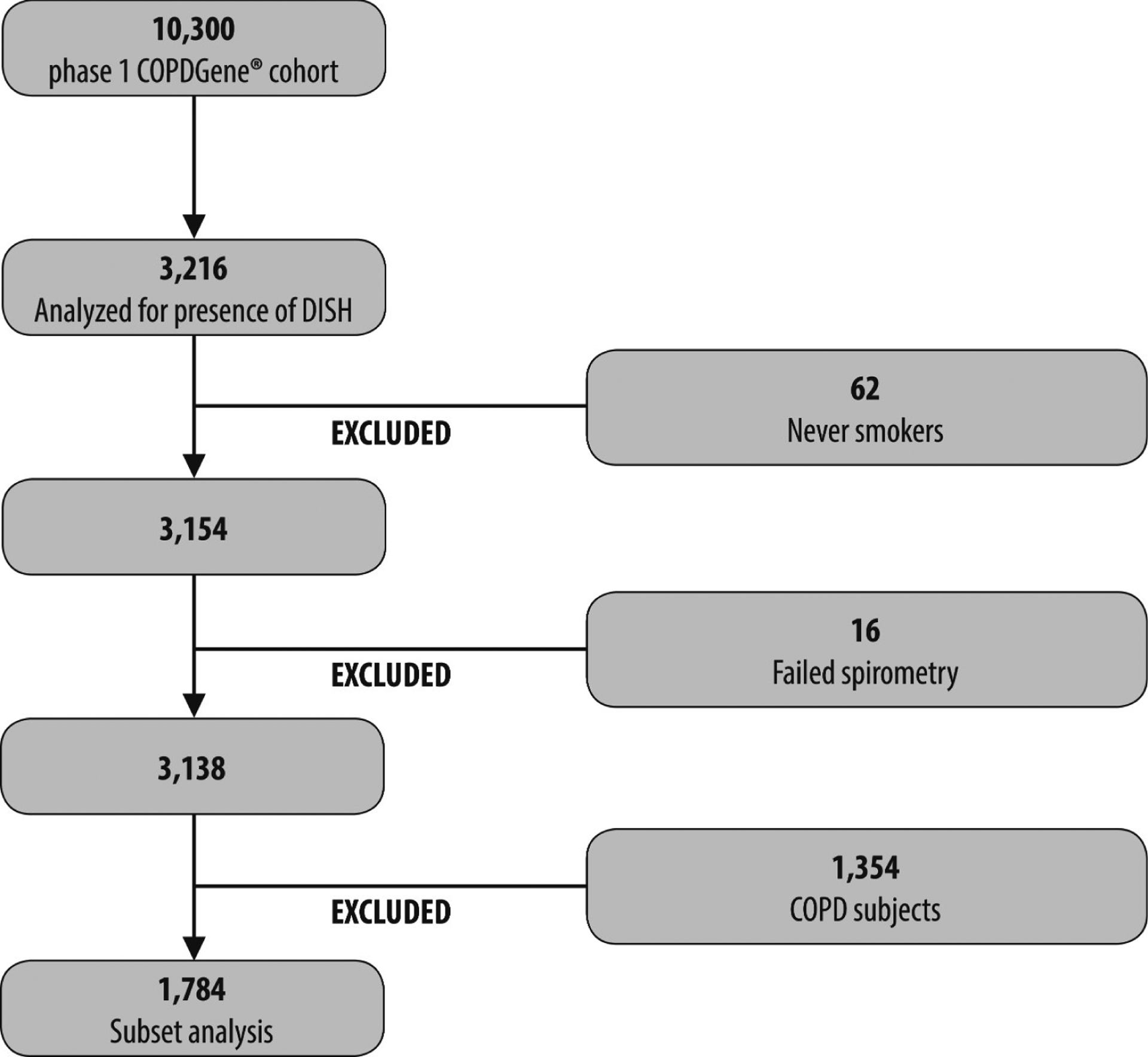

For this substudy, a sample of 1784 current or former smoking non-COPD subjects were included who had had their chest CT scans performed with a calcium calibration phantom [INTable CT scanner pads (Image Analysis Inc.)] and were part of an earlier study of bone density. Figure 1 shows a detailed flow chart. This subset of subjects has been previously described12.

Figure 1.

Flow chart. COPDGene: multicenter observational study designed to identify genetic factors associated with COPD. DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

CT scanning and assessment of DISH.

The scans were acquired using multi-detector CT scanners and standardized protocols. Visual scoring for DISH was performed by trained imaging analysts using TeraRecon software and 3-D sharp reconstructions from the stored image files. A minimum of 2 readers per scan scored scans as DISH if there were 3 or more adjacent levels of flowing osteophytes. Scans with divergent reads were adjudicated by a third reader. Typical flowing lesions with extensive disc narrowing were not scored as DISH. Additionally, the kyphotic angle was measured between Th1 and Th12 in the sagittal view and differences of more than 5° between readers were adjudicated by a third reader.

CT measurement of the lungs.

Quantitative CT measures have been described in detail previously and include the 15th percentile of low-attenuation areas (n = 1743; Perc15, surrogate for emphysema), percentage of lung high attenuation areas between −250 and −600 Hounsfield units [HU; high attenuation area (HAA)] as a surrogate for interstitial lung abnormalities, percentage of gas trapping [n = 1575; expiratory to inspiratory ratio of mean lung attenuation (E/I-ratio MLA)], and airway wall thickness (n = 1737; expressed as the square root of the wall area at a theoretical airway with an internal perimeter of 10 mm; Pi10)13. Further, the total lung capacity (TLC) in inspiration on CT was quantified (n = 1743).

Spirometry and clinical assessment.

All subjects completed pre- and post-bronchodilator (with albuterol) spirometry following ATS guidelines using the EasyOne spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik AG). Studies have shown that spirometry with FVC and FEV1 can be used as a surrogate of restriction but do not define the etiology of restriction14. The estimated prevalence of RSP based on spirometry varies considerably because of different definitions in the literature and the use of bronchodilation. A study investigated the effect of 3 different definitions of the RSP and the difference between pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry on prevalence estimates15. The estimated prevalence in a general population differed most on the choice of pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry.

Presence of an RSP was defined as a fixed threshold of FVC < 80% predicted with a FEV1/FVC ratio > 0.7 on postbronchodilator spirometry15. Definite COPD subjects were excluded based on spirometry (FEV1 < 80% predicted with an FEV1/FVC > 0.7). The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 questionnaire (SF-36; n = 1423), BODE index (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity; n = 1774), and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ; n = 1783) scores were collected and calculated from the phase I or research visit. A 6-min walk test was performed at baseline (n = 1774)16,17,18.

Statistical analysis.

Normally distributed variables were stated as mean (SD) and non-normal data as median (interquartile range, Q1–Q3). Differences between DISH and no DISH and subjects with RSP or no RSP were compared using a Student t test (normal continuous variables), a Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal continuous variables), and a chi-square test (categorical variables). Multivariable logistic regression analysis using backward selection was performed to study the association of RSP with DISH adjusting for age, race, pack-years, height, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, high cholesterol, hypertension (HTN), HAA, Pi10, E/I-ratio, and Perc15. Subjects were grouped by both DISH and RSP status to assess the effect of these variables on quality of life and function. Comparisons were made across groups using ANOVA, with t tests between groups to define significant differences. A significance level of < 0.05 was set. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0.0 (IBM Statistics).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

DISH was present in 236 subjects (13.2%). In subjects with DISH, RSP pulmonary function was significantly more prevalent than in those without DISH, 38.1% versus 19.4% (p < 0.001). In Table 1 characteristics by the presence or absence of DISH are given. DISH subjects were older and more likely to be male (69% male vs 47%). It was less common in African Americans (28% African Americans with DISH vs 39% African Americans among subjects without DISH). DISH subjects were less likely to be current smokers (44% vs 61%) but had significantly higher BMI. Chest CT measures (Perc15, HAA, Pi10, and E/I MLA ratio) were not significantly different between subjects with DISH and no DISH, except that the kyphosis angle was greater in the DISH subjects (39.2 vs 35.1; p < 0.001). HTN, high cholesterol, and diabetes were significantly more present in patients with DISH (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by DISH and no DISH.

| Variables | DISH, n = 236 | No DISH, n = 1548 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictive-like pulmonary function, n (%) | 90 (38.1) | 301 (19.4) | < 0.001 |

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 61.8 (8.8) | 55.9 (8.0) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, M/F | 164/72 | 731/817 | < 0.001 |

| Race, white/black, n | 168/68 | 939/609 | 0.001 |

| Pack-years smoking, mean (SD) | 41.0 (23.4) | 37.7 (20.6) | 0.023 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 104 (44.1) | 950 (61.4) | < 0.001 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 98.5 (19.5) | 84.3 (18.8) | < 0.001 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 173 (9) | 170 (10) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 33.0 (6.5) | 29.0 (6.0) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes present | 62 (26.3%) | 164 (10.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension present | 132 (55.9%) | 577 (37.3%) | < 0.001 |

| High cholesterol | 118 (50%) | 516 (33.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Perc15 Insp (HU), mean (SD) | −902.1 (23.9) | −901.4 (24.2) | 0.664 |

| HAA, %, mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.3) | 0.697 |

| E/I MLA, %, mean (SD) | 82.1 (4.7) | 81.6 (5.2) | 0.819 |

| Pi10, mm, mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.12) | 3.6 (0.12) | 0.218 |

| FEV1, % predicted, mean (SD) | 86.7 (16.0) | 92.3 (15.4) | < 0.001 |

| FVC, % predicted, mean (SD) | 84.7 (15.2) | 92.0 (15.0) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.592 |

| TLC on CT, ltr | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.3) | 0.027 |

| Kyphotic angle, mean (SD) | 39.2 (10.3) | 35.1 (10.6) | < 0.001 |

DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis; BMI: body mass index; Perc15: HU value at the 15th percentile (n = 1743); E/I MLA: expiratory to inspiratory ratio of mean lung attenuation (n = 1575); Pi10: square root of wall area of a 10-mm lumen perimeter (n = 1737); FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; HAA: high attenuation area; TLC: total lung capacity (n = 1743); CT: computed tomography; HU: Hounsfield units

RSP pulmonary function was present in 391 subjects (21.9%) of the total group of 1784 subjects. The RSP subjects had significantly more pack-years of smoking (42.4 vs 36.9, p < 0.001) and were slightly more likely to be current smokers (64% vs 58%, p = 0.015). Details on the baseline characteristics stratified by RSP pulmonary function and normal spirometry are shown in Table 2. BMI was significantly higher in the subjects with RSP [mean (SD) 32.1 (7.2) and 28.9 (5.7); p < 0.001]. There was no significant difference in kyphotic angle between the 2 groups [mean (SD) 35.0 (11.5) and 35.8 (10.4); p = 0.180]. Perc15 inspiration was significantly higher in those with RSP pulmonary function [mean (SD) HU −887 (27) vs −908 (22) HU; p < 0.001]. The mean (SD) HAA was not different in those with RSP pulmonary function compared to the normal group [3.9% (1.4) and 3.8% (1.4); p = 0.703]. The RSP pulmonary function group had a significantly higher Pi10 compared to the normal group [3.71 (0.13) vs 3.63 (0.11) mm; p < 0.001]. The E/I MLA ratio was comparable in both groups. The mean (SD) TLC on CT was significantly lower in those with RSP pulmonary function [4.6 (1.1) and 5.5 (1.3); p < 0.001].

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics stratified by presence of RSP pulmonary function.

| Variables | RSP Pulmonary Function, n = 391 | Normal, n = 1393 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| DISH | 90 (23.0%) | 146 (10.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 57.5 (8.6) | 56.5 (8.3) | 0.031 |

| Sex, M/F | 201/190 | 694/699 | 0.310 |

| Race, white/black, n | 233/158 | 874/519 | 0.140 |

| Pack-years smoking, mean (SD) | 42.4 (24.1) | 36.9 (20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 250 (63.9) | 804 (57.7) | 0.015 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 94.1 (21.6) | 84.0 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 171 (10) | 170 (10) | 0.098 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 32.1 (7.2) | 28.9 (5.7) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes present | 62 (26.3%) | 164 (10.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension present | 132 (55.9%) | 577 (37.3%) | < 0.001 |

| High cholesterol | 118 (50%) | 516 (33.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Perc15 Insp (HU), mean (SD) | −887.0 (26.5) | −905.5 (21.8) | < 0.001 |

| HAA (%), mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.4) | 0.703 |

| E/I MLA (%), mean (SD) | 82.1 (5.4) | 81.5 (5.0) | 0.092 |

| Pi10, mm, mean (SD) | 3.71 (0.13) | 3.63 (0.11) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1, % predicted, mean (SD) | 72.4 (10.0) | 96.9 (12.4) | < 0.001 |

| FVC, % predicted, mean (SD) | 71.0 (7.9) | 96.7 (11.3) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.79 (0.06) | 0.78 (0.05) | 0.001 |

| TLC on CT, ltr | 4.6 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| Kyphotic angle, mean (SD) | 35.0 (11.5) | 35.8 (10.4) | 0.180 |

DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis; RSP: restrictive spirometric pattern; BMI: body mass index; Perc15: HU value at the 15th percentile (n = 1743); E/I MLA: expiratory to inspiratory ratio of mean lung attenuation (n = 1575); Pi10: square root of wall area of a 10-mm lumen perimeter (n = 1737); FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; HAA: high attenuation area; TLC: total lung capacity (n = 1743); CT: computed tomography; HU: Hounsfield units.

Univariable and multivariable associations with the presence of RSP pulmonary function.

Table 3 lists the outcomes of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis of the presence of RSP. At univariable analysis, subjects with DISH had a significantly higher OR of having RSP (2.55, CI 95% 1.91–3.42). At multivariable logistic regression analysis, the presence of DISH remained significantly associated with RSP after adjusting for age, race, pack-years, height, BMI, diabetes, HTN, high cholesterol, HAA, Pi10, E/I-ratio, and Perc15 (OR 1.78, CI 95% 1.22–2.60; p = 0.003). Detailed results of the multivariable logistic regression are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between RSP pulmonary function and DISH: results of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis.

| Variable | Increment or Comparison | Univariable, OR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable, OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISH | Yes/No | 2.55 (1.91–3.42) | < 0.001 | 1.78 (1.22–2.60) | 0.003 |

| Age | +1 yr | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.032 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.002 |

| Sex | Male vs female | 1.01 (0.85–1.33) | 0.579 | ||

| Race | White vs black | 1.14 (0.91–1.44) | 0.257 | 1.56 (1.13–2.16) | 0.007 |

| Pack-years smoking | +1 pack-yr | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.007 |

| Smoking status | Current vs former | 1.30 (1.03–1.64) | 0.027 | ||

| Weight | +1 kg | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | < 0.001 | ||

| Height | +1 cm | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.099 | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.001 |

| BMI | +1 kg/m2 | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | Present vs absent | 2.30 (1.71–3.10) | < 0.001 | ||

| Hypertension | Present vs absent | 1.64 (1.30–2.05) | < 0.001 | ||

| High cholesterol | Present vs absent | 1.25 (1.00–1.58) | 0.055 | ||

| Pi10 | +0.1 mm | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 0.001 | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | < 0.001 |

| E/I MLA ratio | +1% | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 0.093 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.039 |

| HAA | +1% | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 0.703 | ||

| Perc15 | +1 HU | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | < 0.001 |

| Kyphotic angle | +1 degree | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.180 |

DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis; RSP: restrictive spirometric pattern; BMI: body mass index; Perc15: HU value at the 15th percentile (n = 1743); E/I MLA: expiratory to inspiratory ratio of mean lung attenuation (n = 1575); Pi10: square root of wall area of a 10-mm lumen perimeter (n = 1737); HAA: high attenuation area; HU: Hounsfield units.

Association between DISH, RSP, and quality of life metrics BODE and 6-min walk distance.

We assessed DISH alone compared to the groups with no DISH/no RSP and found that the effect of DISH was a significant reduction in 6-min walk distance [1480 (351) feet for DISH alone vs 1560 (323) feet for no DISH/no RSP; p = 0.003], and yet worse 6-min walk distance for those with both DISH and RSP disease (Table 4). When combined with RSP, the additional effect of DISH was a higher/better score for the SF-36 mental component summary score [50.5 (10.4) vs 46.5 (12.5); p = 0.009] than RSP alone. Similarly, the SGRQ total score was better (lower) in RSP subjects who also had DISH [26.2 (22.8) vs 31.6 (23.7); p = 0.03]. The RSP groups both with and without DISH had significantly worse spirometry, dyspnea, SGRQ, BODE, and SF-36 scores.

Table 4.

Association between both DISH status and presence or absence of RSP pulmonary function on quality of life and function.

| Variables | No Dish, No RSP Pulmonary Function | DISH + No RSP Pulmonary Function | RSP Pulmonary Function + No DISH | Both DISH and RSP Pulmonary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. subjects | 1247 | 146 | 301 | 90 |

| FEV1, % predicted, mean (SD) | 97.1 (12.4) | 94.9 (12.7) | 72.2 (9.7)* | 73.3 (10.8)* |

| FVC, % predicted, mean (SD) | 97.1 (11.4) | 93.2 (11.7)* | 71.1 (7.8)*^ | 70.8 (8.5)*^ |

| mMRC Dyspnea Scale, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.5)*^ | 1.3 (1.5)*^ |

| SGRQ Total, mean (SD) | 17.8 (19.0) | 16.8 (17.4) | 31.6 (23.7)*^ | 26.2 (22.8)*^† |

| SF-36 PCS, mean (SD) | 48.0 (9.8) | 47.8 (9.4) | 42.1 (10.5)*^ | 42.6 (11.0)* |

| SF-36 MCS, mean (SD) | 49.1 (11.3) | 50.6 (11.3) | 46.5 (12.5)*^ | 50.5 (10.4)† |

| BODE score, mean (SD) | 0.52 (0.93) | 0.43 (0.84) | 1.3 (1.4)*^ | 1.0 (1.4)*^ |

| 6-min walk distance (feet), mean (SD) | 1560 (323)^ | 1480 (351) | 1326 (347)*^ | 1314 (390)*^ |

p < 0.0001 for comparison to No DISH/No PRISm pulmonary function group.

p < 0.001 for comparison to DISH/no PRISm pulmonary function.

p < 0.05 for comparison to PRISm pulmonary function/no DISH.

Subjects grouped by both DISH status and presence or absence of RSP pulmonary function to assess the effect of DISH and or RSP on quality of life and function. Comparisons were made across groups using ANOVA, with t tests between groups to define significant differences.

DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis; RSP: restrictive spirometric pattern; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short-form 36 questionnaire (n = 1423); BODE index: Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity (n = 1774); SGRQ: St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (n = 1783); mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; PCS: physical component score; MCS: mental component score.

DISCUSSION

We found, after correction for several known causes of restrictive lung function, that DISH was significantly associated with RSP in a cohort of current and former smokers, excluding smokers with a low FEV1/FVC ratio. DISH is a common “incidental finding” in imaging studies. Our findings contribute to the understanding of the association between DISH and pulmonary function abnormalities, and our data suggest that DISH may be a previously unrecognized cause of extrinsic restriction-like pulmonary function in subjects with a substantial smoking history.

In the last decade, multiple population-based studies have shown that a significant proportion of the general adult population has RSP or restriction-like pattern on spirometry19,20. In heavy smokers without prior known ILD in the COPDGene cohort, a large portion of the subjects likely had this physiology as a result of small airway inflammatory disease. This is supported in our data by a significant increase in Pi10 in the RSP group. It is important to identify restrictive elements that may also contribute to this physiology. The common restrictive elements that contribute to RSP can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic factors7. Intrinsic factors can be further split into interstitial, pleural, and alveolar causes. In this study, we corrected for alveolar disease such as emphysema, and did not observe significant amounts of pleural fluid in these subjects. Our cohort excluded subjects with diagnosed ILD and screened CT scans after enrollment for ILD. We further assessed for interstitial abnormalities by quantifying HAA of the lung. We found no differences in HAA in those with or without RSP and those with or without DISH. Known extrinsic factors are obesity, ascites, neuromuscular diseases, and kyphoscoliosis20.

In our regression models, we corrected for 2 important extrinsic factors that may cause RSP: obesity (BMI) and kyphosis. There was no difference between the groups in kyphosis; however, we did not look into (kypho)scoliosis. It has been shown that longterm milder degrees of scoliosis can influence respiratory function and there can also be a role for rib ankylosis and deformities21. We did not expect scoliosis to be a major issue because previous studies have suggested that especially severe scoliosis (> 60° Cobb angle) has a substantial effect on lung function22. None of the included DISH participants had scoliosis of this severity, and the Cobb angle was the same in the group with RSP compared to those with normal lung function. While we did not correct for neuromuscular disease, it cannot explain our observations in this cohort owing to the low prevalence of neuromuscular disease in the general population (1–10 per 100,000)23.

Our data suggest that DISH may create an extrinsic restrictive factor that contributes to RSP in heavy smokers without known ILD. This pattern has been suggested in a previous study in which the thoracic cage is forcing individuals to ventilate by diaphragm contraction and only eventually leading to restriction of pulmonary function24. A previous case report suggested that advanced DISH creates a rigid “thoracic cage” because of the osseous bridging of vertebral bodies, ribs, and sternum, reducing the mechanism of lung expansion to diaphragm contractions only5. Our findings support that an extrathoracic cause has to be considered as an explanation for the DISH contribution to the RSP. DISH should also be included in the differential diagnosis of RSP, especially after the elimination of other common restrictive causes. Because a chest CT scan is often performed when restriction is diagnosed, it is possible to specifically look for the presence of DISH. Our study suggests that DISH may affect thoracic cage mobility, and we demonstrate a novel potential extrinsic factor for RSP spirometry in current and former smokers. RSP spirometry in smokers independent of DISH is strongly associated with more dyspnea, worse BODE index, and lower walking distance, consistent with a primary effect of the smoking-induced lung disease. The presence of DISH is shown to have an additional negative influence on walking distance in current and former smokers at high risk for progressive COPD.

RSP with and without DISH is associated with worse spirometry, more dyspnea, worse quality of life by SGRQ and SF-36, worse BODE scores and lower 6-min walk distances in this group of current and former smokers without spirometric COPD. This may be related to small airways inflammation that is associated with early COPD in smokers. We identify DISH alone and in association with RSP pulmonary function, but the major effect of DISH appears to be a reduction in 6-min walk distance in those subjects who have DISH alone without associated RSP pulmonary function. This suggests that the occurrence of DISH in combination with smoking-induced airway inflammatory disease causes a measurable decrease in functional performance (6-min walk).

RSP has been shown to be associated with a decreased quality of life based on SGRQ scores23, and a study including 2 large population-based cohorts of adults showed that the presence of RSP significantly affects the physical health component of quality of life25,26. However, when DISH is associated with RSP, subjects have significantly better SGRQ Total score. This suggests that the effect of this extrinsic restriction on respiratory quality of life has less negative effect on symptoms other than exercise performance.

It has been hypothesized that DISH is associated with the metabolic syndrome. In our data we observed that both DISH and RSP are associated with higher BMI, more pack-years, diabetes, HTN, and high cholesterol. Further, all the univariate OR were significant. After multivariable adjustment, higher BMI and more smoking remained in the model; the association between RSP and DISH weakened but remained significant. This suggests that to some extent the association between DISH and RSP is direct. In cross-sectional studies, care is needed with causal assumptions. Our observation on the association between DISH and cardiometabolic factors supports further causal studies into the connections among RSP, DISH, and metabolic syndrome27,28.

Strengths of our study include the well-characterized cohort of smokers and the use of postbronchodilator spirometry. To our knowledge this is the largest study examining DISH and its relation to RSP in current and former smokers. There are some study limitations: selection criteria limited the cohort to heavy current or former smokers; RSP in heavy smokers remains a complex mixture of subjects with progressive obstruction characterized as the early stages of small airway disease and restriction from multiple etiologies.

The definition of RSP pulmonary function used in our study is the same as that commonly used to define restriction-like physiology in general population studies15. Other definitions could be considered [i.e., FVC < 80% and FEV1/FVC > lower limit of normal (LLN) and FVC < LLN and FEV1/FVC > LLN]15. A study investigated the prevalence of an RSP in a general population of 726 subjects in the age range 21–86 years by obtaining spirometry15. The prevalence of RSP was calculated according to 3 different definitions based on pre- as well as postbronchodilator spirometry. This study showed no significant differences among 3 definitions of RSP. On the other hand, the use of pre- and postbronchodilator showed more significant variation in terms of RSP15.

We found that DISH is significantly associated with RSP in a cohort of heavy smokers. The association of DISH persisted after extensive correction for known intrinsic restrictive factors, supporting the hypothesis that DISH can potentially lead to a novel extrinsic cause of restrictive-like spirometry in a rigid thoracic cage. To some extent, DISH and RSP may be components of the metabolic syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (award number U01 HL089897, award number U01 HL089856). Dr. E.K. Silverman has received grant and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

ONLINE SUPPLEMENT

Supplementary material accompanies the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsukamoto Y, Onitsuka H, Lee K. Radiologic aspects of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in the spine. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1977;129:913–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Julkunen H, Heinonen OP, Knekt P, Maatela J. The epidemiology of hyperostosis of the spine together with its symptoms and related mortality in a general population. Scand J Rheumatol 1975;4:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westerveld LA, van Ufford HM, Verlaan JJ, Oner FC. The prevalence of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in an outpatient population in the Netherlands. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1635–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vezyroglou G, Mitropoulos A, Antoniadis C. A metabolic syndrome in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: a controlled study. J Rheumatol 1996;23:672–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida M, Kibe A, Aizawa H, Matsumoto K, Inoue H, Koto H, et al. [Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis with fibrobullous change in upper lung lobes and dyspnea due to limitation of thoracic cage]. [Article in Japanese] Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 1999;37:823–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oudkerk SF, Buckens CF, Mali WP, De Koning HJ, Öner FC, Vliegenthart R, et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis is associated with lower lung volumes in current and former smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:241–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson HA. Respiratory conditions update: restrictive lung disease. FP Essent 2016;448:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan ES, Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Hokanson JE, Regan EA, Make BJ, et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res 2014;15:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan ES, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Regan EA, Make BJ, Lynch DA, et al. Clinical and radiographic predictors of GOLD-unclassified smokers in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD 2010;7:32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaramillo JD, Wilson C, Stinson DS, Lynch DA, Bowler RP, Lutz S, et al. Reduced bone density and vertebral fractures in smokers. Men and COPD patients at increased risk. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:648–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroeder JD, McKenzie AS, Zach JA, Wilson CG, Curran-Everett D, Stinson DS, et al. Relationships between airflow obstruction and quantitative CT measurements of emphysema, air trapping, and airways in subjects with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201:W460–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanney MP, Beckert LE, Frampton CM, Wallace LA, Jensen RL, Crapo RO. Validity of the American Thoracic Society and other spirometric algorithms using FVC and forced expiratory volume at 6 s for predicting a reduced total lung capacity. Chest 2004;126:1861–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backman H, Eriksson B, Hedman L, Stridsman C, Jansson SA, Sovijärvi A, et al. Restrictive spirometric pattern in the general adult population: methods of defining the condition and consequences on prevalence. Respir Med 2016;120:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ATS Committee. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godfrey MS, Jankowich MD. The vital capacity is vital: epidemiology and clinical significance of the restrictive spirometry pattern. Chest 2016;149:238–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, García-Río F, Muñoz L, Sánchez G, Sobradillo V, et al. Spirometrically-defined restrictive ventilatory defect: population variability and individual determinants. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang GS, Park YH, Taylor JA, Sartoris DJ, Seragini F, Pathria MN, et al. Hyperostosis of ribs: association with vertebral ossification. J Rheumatol 1993;20:2073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barois A Respiratory problems in severe scoliosis. Bull Acad Natl Med 1999;183:721–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deenen JC, Horlings CG, Verschuuren JJ, Verbeek AL, van Engelen BG. The epidemiology of neuromuscular disorders: a comprehensive overview of the literature. J Neuromuscul Dis 2015;2:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verlaan JJ, Oner FC, Maat GJ. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in ancient clergymen. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1129–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Venker C, Ceccato CM, Halonen M, Martinez FD. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax 2010;65:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerra S, Carsin AE, Keidel D, Sunyer J, Leynaert B, Janson C, et al. Health-related quality of life and risk factors associated with spirometric restriction. Eur Respir J 2017;25:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baffi CW, Wood L, Winnica D, Strollo PJ Jr, Gladwin MT, Que LG, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the lung. Chest 2016;149:1525–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pappone N, Ambrosino P, Di Minno MND, Iervolino S. Is diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis a disease or a syndrome? Rheumatology 2017;56:1635–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.