Keywords: alcohol, crayfish, inhibition, neurons, social

Abstract

We report here that prior social experience modified the behavioral responses of adult crayfish to acute alcohol exposure. Animals housed individually for 1 wk before alcohol exposure were less sensitive to the intoxicating effects of alcohol than animals housed in groups, and these differences are based on changes in the nervous system rather than differences in alcohol uptake. To elucidate the underlying neural mechanisms, we investigated the neurophysiological responses of the lateral giant (LG) interneurons after alcohol exposure. Specifically, we measured the interactions between alcohol and different GABAA-receptor antagonists and agonists in reduced crayfish preparations devoid of brain-derived tonic GABAergic inhibition. We found that alcohol significantly increased the postsynaptic potential of the LG neurons, but contrary to our behavioral observations, the results were similar for isolated and communal animals. The GABAA-receptor antagonist picrotoxin, however, facilitated LG postsynaptic potentials more strongly in communal crayfish, which altered the neurocellular interactions with alcohol, whereas TPMPA [(1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid], an antagonist directed against GABAA-receptors with ρ subunits, did not produce any effects. Muscimol, an agonist for GABAA-receptors, blocked the stimulating effects of alcohol, but this was independent of prior social history. THIP [4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol], an agonist directed against GABAA-receptors with δ subunits, which were not previously known to exist in the LG circuit, replicated the suppressing effects of muscimol. Together, our findings provide strong evidence that alcohol interacts with the crayfish GABAergic system, and the interplay between prior social experience and acute alcohol intoxication might be linked to changes in the expression and function of specific GABAA-receptor subtypes.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The complex interactions between alcohol and prior social experience are still poorly understood. Our work demonstrates that socially isolated crayfish exhibit lower neurobehavioral sensitivity to acute ethanol compared with communally housed animals, and this socially mediated effect is based on changes in the nervous systems rather than on differences in uptake or metabolism. By combining intracellular neurophysiology and neuropharmacology, we investigated the role of the main inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, and its receptor subtypes, in shaping this process.

INTRODUCTION

Ethyl alcohol is a highly common drug of use, but one with particularly detrimental personal, social, and economic consequences. Alcohol is responsible for over 5% of deaths worldwide (1). In the United States, alcohol is responsible for almost 10% of deaths among the working age population, and excessive drinking cost $249 billion dollars in 2010 (2, 3). Despite this, the mechanisms through which alcohol exerts its neurobehavioral effects are poorly understood. Although most drugs bind to specific receptor types in the nervous system (e.g., opiates and opioids to opioid receptors, cannabis to endocannabinoid receptors) or receptor subtypes (e.g., nicotine and muscarine to different acetylcholine receptor subtypes), ethanol does not (4). Instead it affects the serotonergic system (5), glutamatergic receptors (6), GABAergic receptors (7), and even voltage-gated ion channels (8). Thus, the study of alcohol’s effects on nervous system function and behavior is complicated, and overall progress in understanding the underlying mechanisms has been slow. This translates to limited success and poor outcomes in treating alcohol-related disease in humans (e.g., 9).

Ethanol (EtOH) interacts with the GABAergic system and contributes to its modulation of behavior (10), and it has particularly strong effects on tonic inhibitory currents (11). Many GABA receptors are sensitive to EtOH, including the extrasynaptic receptors containing δ (delta) subunits, which often mediate tonic inhibition (10, 12, 13), and GABA receptors containing ρ (rho) subunits, which underlie a similar type of inhibition (14–16). However, the effects of EtOH within the GABA receptor family are complex. Most GABAA receptors are potentiated by EtOH, but GABAA-ρ1 receptors are inhibited (16). Within the field of GABA-related alcohol research, there are conflicting models of how EtOH’s cellular mechanisms connect to its behavioral manifestation (10), and results remain inconclusive (11). The complex interplay between EtOH and multiple neurotransmitter systems, combined with the different roles it may have within subsets of GABA receptor targets, makes animals of lower complexity with accessible nervous systems promising models for studying the relevant cellular-molecular mechanisms.

Crayfish have been historically productive model organisms for studying inhibitory processes of the nervous system. The inhibitory nature of GABA (then described as “Factor I”) was first studied using a crayfish preparation (17, 18). Several features of crayfish nervous systems in particular make them amenable as a productive organism for neurocellular and pharmacological investigation. The nervous system is readily accessible, and the neurons are large, with axons up to hundreds of microns in diameter in the escape circuits (19), allowing for intracellular, single-cell recordings. The nervous system is hardy, surviving for hours in a dish, even when removed from the rest of the animal. Furthermore, the neural circuits contain fewer neurons compared with vertebrates, and especially mammals, and many are individually identified. In some cases, such as the extensively studied escape circuits, neuron activity translates directly to behavioral output (20). The lateral giant (LG) interneuron, in particular, is arguably part of one of the best understood neural circuits in the animal kingdom (20).

Crayfish have three neural circuits that they use to execute as many tail-flip behaviors in response to predatory threats (21). Two of them contain giant interneurons, and to respond quickly, rapid strikes trigger action potentials in either of two pairs. Attacks to the front of the animal, or quickly approaching visual stimuli, will trigger the medial giant (MG) interneuron (20, 22–25). The medial giants originate in the brain and project the length of the animal. An action potential in the MG will recruit motor neurons that activate flexion muscles in all abdominal segments of the tail (20). The contraction of these phasic flexors causes the animal to rapidly curl its tail underneath its body, projecting itself rapidly backward to escape a frontal attack.

The LG circuit consists of paired neurons in each abdominal segment, electrically coupled to their contralateral homologue, as well as the LG neurons located more posteriorly (19). The LG receives most of its inputs in the tail and responds to sharp, phasic, mechanosensory stimuli (25–27). Like the MG, a single impulse in the LG is sufficient to initiate the complete tail-flip escape behavior. The action potential in the LG drives motorneurons that cause the contraction of the phasic flexor muscles in the anterior abdominal segments, resulting in partial flexion of the tail, and moving the animal forward and up in a jackknife motion, away from a caudal attack (20, 21, 28).

Postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) in the LG interneuron have characteristic components visible in intracellular recordings following the stimulation of nerves containing primary sensory afferents, allowing the investigation of different neurotransmitter actions depending on the time point selected for analysis. Three distinct parts of the LG PSP have been described (29). An early α component is comprised of excitatory inputs from electrical synapses formed by primary afferents that are excited by deflection of hairs and proprioceptors; a slightly delayed β component that gives rise to a single action potential and is formed by a polysynaptic chemical pathway involving mechanosensory interneurons; and a late γ component, which is considered to be mostly composed of inhibitory inputs (30; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A: circuit diagram of the preparation used for electrophysiology experiments. PSPs in the LG neuron were evoked with electric stimulation of the sensory nerves that contain the primary sensory afferents (SA) and recorded with an intracellular electrode in the axon of LG. A second extracellular electrode was placed between more rostral ganglia to monitor ascending LG action potentials. The SAs connect to LG directly via electrical synapses and to sensory interneurons (SI) via chemical synapses. Excitatory SIs connect to LG via electrical synapses, while unidentified interneurons provide delayed inhibition. The broken line shown in parallel to the LG axon denotes descending tonic inhibition, which was eliminated in this preparation of the isolated nerve cord. B: an example recording of LG PSP just below threshold (black trace) overlaid on an LG action potential (gray trace). The gray trace was taken 90 s after the black one. The action potential is truncated. The arrowhead points to the stimulus artifact, and the black arrows point to LG PSP time points that are 3 ms (“early”) and 5 ms (“late”) after stimulus onset. The Greek letters indicate the different phases of the LG PSP that are generated by electrical (α) as well as chemical (excitatory, β; mostly inhibitory, γ) inputs from sensory afferent (SA) and sensory interneurons (SI). LG, lateral giant; PSPs, postsynaptic potentials.

Only a small number of studies have investigated the effects of alcohol on crayfish behavior and nervous system function (31–35), and we have previously shown that juvenile crayfish respond behaviorally to EtOH exposure in a manner similar to that of humans and other intoxicated animals (36). First, crayfish became hyperactive and adopted an “aggressive” stance. Following this, they showed clear signs of disinhibition, such as spontaneous tail-flip behavior in the absence of any threatening stimuli. Eventually, they began to lose coordination, fell on their backs, and were unable to right themselves (31, 36). The behavioral disinhibition was paralleled in the LG neuron, which became more excitable when exposed to alcohol in ex vivo preparations (36). It was previously suggested that an interaction between EtOH and GABAergic inhibition could underlie this effect, because the threshold for LG-mediated escape behavior is modulated by tonic GABAergic inhibition (37, 38). This tonic inhibition of LG is due to descending inputs from the crayfish brain, and it can be removed by sucrose block or surgical cut of the nerve cord between the thorax and the abdomen (39). In most organisms, tonic GABAergic inhibition is mediated by extrasynaptic GABAA-δ receptors (40), which are highly sensitive to EtOH (12). Interestingly, removal of descending inhibitory tonic inputs did reduce the facilitatory effects of EtOH on the LG neuron in crayfish (36).

Ethanol interacts with the crayfish MG escape circuit as well (41). Surprisingly, exposure to the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol had only a minor effect on postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) of the MG neuron that were evoked by mechanosensory inputs, but washout of the drug caused a major decrease in MG PSP, and the same pattern was seen with the GABA receptor antagonist picrotoxin. The similarity between the results with muscimol and picrotoxin suggested that muscimol may be antagonizing GABA receptors in the MG circuit, possibly GABAA-ρ subtype receptors, where muscimol may act as a competitive inhibitor for binding sites (42). Importantly, when EtOH was applied after muscimol pretreatment to the ex vivo crayfish preparations, the otherwise potentiating effects of ethanol on the MG PSPs were eliminated (41).

Social experience changes the neurobehavioral sensitivity of juvenile crayfish to acute alcohol (36). Communally housed crayfish became intoxicated more quickly compared with animals that had been socially isolated for 1 wk before acute EtOH exposure. In addition, the lower behavioral sensitivity to EtOH in isolates was paralleled on the single neuron level, as socially isolated crayfish showed a heightened threshold for EtOH-mediated activation of the LG neuron when compared with socially experienced animals.

Importantly, when descending GABAergic tonic inputs were removed, the differences in LG excitability between socially experienced and socially naïve animals disappeared at low EtOH concentrations (36). These findings suggested that tonic inhibition and the associated GABA receptors might play an important role in mediating the socially dependent responses to acute EtOH, possibly based on differences in the expression of GABA receptors shaped by prior social experiences.

To gain a more complete understanding of the neurocellular interactions between EtOH and GABA receptors in crayfish, we conducted a series of pharmacological studies. Experiments were performed on the LG circuit using acute EtOH exposure following pretreatment with either a GABAA-receptor antagonist (picrotoxin) or a GABAA-receptor agonist (muscimol). To test the possibility that specific GABAA receptor subtypes mediate portions of the LG’s inhibition and its interaction with EtOH, a GABAA-ρ receptor-specific antagonist [(1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid (TPMPA)] and a GABAA-δ specific agonist [4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol (THIP)] were used. We performed these experiments in the isolated abdominal portion of the ventral nerve cord that contains the entire, intact, LG circuit but removes all tonic inhibition from our preparations. Both socially experienced and socially isolated animals were tested. In addition, we also present new behavioral data showing that the socially mediated sensitivity to ethanol generalizes to freely behaving adult crayfish, and the difference in EtOH sensitivity is not based on differences in hemolymph EtOH concentrations.

METHODS

Animals

Crayfish used in behavioral experiments were adult male Procambarus clarkii, obtained from a commercial supplier (Atchafalaya Biological). They were housed in large communal housing tanks (76 × 30 × 30 cm; L:W:H) with six to seven other crayfish and kept on a 12-h light:dark schedule at constant temperature of 22°C ± 1.5°C. They were fed shrimp pellets (Aqua Pets Americas) twice weekly, approximately two medium-sized pellets for each crayfish present in the tank. One week before testing, some crayfish were placed in complete social isolation by transferring them into small individual tanks (15 × 8 × 10 cm) and fed one shrimp pellet on the day of isolation. The water in communal tanks was constantly circulated and filtered using an aquarium pump (Tetra Spectrum Brands), whereas the small isolation tanks were equipped with air stones for water oxygenation (BubbleMac Industries). COMs (communally housed crayfish) were taken directly from one of the communal tanks, and ISOs (socially isolated crayfish) were taken from their isolation tanks. Both were weighed and measured before being transferred to the experimental (i.e., EtOH-containing) tank and tested individually.

For electrophysiology and neuropharmacology, adult crayfish of both sexes (P. clarkii) were obtained from commercial suppliers (Niles Biological Inc., or Carolina Biological Supply Company). Maintenance and feeding of these animals was identical to the behavioral experiments described above, except that some large communal tanks were shared by up to 13 individual crayfish, and the social isolation period was between 7 and 10 days.

No animals were used that had signs of injury, were missing two or more walking legs, either claw, or were still noticeably soft from a recent molt. Isolated animals were not used if they had molted in isolation, regardless of exoskeleton hardness. Each animal was used only once in a single experiment.

Experimental Procedures

Behavior.

Procedures followed a previously published protocol using juvenile crayfish (36) and customized for adult animals. We created EtOH water baths by mixing 100% ethyl alcohol (Ethyl Alcohol 200 Proof) with distilled water. Crayfish were transferred into experimental tanks (20 × 12 × 13 cm; L:W:H) filled with 1,500 mL of water containing 2 M EtOH solution. This concentration was used because we have previously shown that the effects of EtOH on crayfish behavior are dose dependent, and crayfish take up roughly 10% of the outside EtOH concentration into their bloodstream within the first 1–2 h of exposure (31, 33, 34, 36). The behavior of the animals was filmed with a digital video camera facing the longer side of the tank for a total of 60 min. Data were stored in S-VHS format and later reviewed using single-frame video analysis. The onset (first observation) of different behavioral changes evoked by EtOH intoxication was measured in minutes after the start of the trial. The onset of tail-flipping behavior was determined as the first occurrence of a tail-flip (which was always followed by additional tail-flips), and supine posture was measured when the animal first landed on its back and was unable to immediately right itself. At the end of the experimental period (i.e., after 60 min of recording), the animals were transferred into a new tank with fresh deionized water to detoxify.

The effects of 2 M EtOH on behavior were measured in individual crayfish that were communally housed (COMs) and in animals that were socially isolated (ISOs) for 1 wk before EtOH exposure. COMs (N = 19; 8.71 ± 0.36 cm, 18.15 ± 2.94 g) were similar in size and weight compared with ISOs (N = 20; 8.70 ± 0.37 cm, 18.67 ± 2.21 g). Experiments and video analysis were performed by two different researchers; the researcher conducting the video analysis was blind to the condition of the animals.

Hemolymph EtOH concentration.

Ethanol absorption in crayfish hemolymph was measured in separate groups of ISOs and COMs after immersion for 30 min in experimental tanks (20 × 12 × 13 cm; L:W:H) filled with 1.5 L of a 2 M EtOH solution. Directly after exposure, animals were anesthetized on ice for 15 min and hemolymph (∼150 µL) was drawn from the ventral sinus using a 1-mL syringe fitted with a 26 gauge needle. In all, 100 µL of the drawn hemolymph was rapidly transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing 100 µL of an anticoagulant solution (0.11 M Na Citrate, 0.1 M NaCl; 43), centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 RPM and immediately stored at −20°C. After samples had thawed to room temperature, EtOH concentration in the hemolymph was measured using a Biochemistry Analyzer (YSI 2700 SELECT). The instrument was equipped with Ethanol Membrane (YSI 2786) and Carbonate Buffer (YSI 1579). It was calibrated using Ethanol Standards (YSI 2790) of 2.0 g/L and 3.2 g/L. For each sample, average EtOH concentrations were calculated from three consecutive measurements. Samples were reanalyzed several months later after multiple thawing-freezing cycles to assess storage life and reproducibility. The remeasured values of most samples (>80%) were within 10% of the original value, and we decided to exclude three samples (two ISOs, one COM) from the final data set that did not meet this criterion. Thus, data presented are from six ISOs (9.42 ± 0.19 cm, 25.10 ± 1.55 g) and seven COMs (9.07 ± 0.60 cm, 25.52 ± 5.42 g). Neither weight (Mann–Whitney U test: P = 0.731) nor size (Mann–Whitney U test: P = 0.234) was significantly different between these two groups. Because groups were composed of males and females, we also examined differences between sexes (see results).

Neuropharmacology.

Animals used in electrophysiology experiments were anesthetized on ice for 15 min before any manipulations. The abdomen was removed with scissors and the ventral carapace of the abdomen cut bilaterally down to the tail fan with a smaller pair of scissors. The ventromedial strip of carapace was then removed with forceps, exposing the ventral nerve cord. Deeper incisions were made along the lateral sides of the tail muscle to remove connections between the nerve cord and innervated tissue. The scissors were then placed in the phasic tail flexor muscles, dorsal to the nerve cord, and used to disconnect the third nerve root from its targets. Incisions were made along the very caudal end of the tail interior, to cut the nerves of the last abdominal ganglion (A6). The nerve cord was then lifted with forceps and placed in the experimental dish with saline.

The dish was placed in a holder in the experimental cage and grounded. Extracellular electrodes were then placed on the lateral nerve roots of A6 for stimulation of sensory afferents that connect to LG and a rostral site on the cord for confirmation of giant neuron activity; an intracellular electrode was used to impale the LG neuron (Fig. 1A). Intracellular electrodes were made of borosilicate glass capillary tubes (World Precision Instruments) and were pulled with a P-97 electrode puller (Sutter Instruments). Electrodes were filled with 2 M potassium acetate and mounted on HS-1A headstages (Axon Instruments). Silver wire was used as the conductive contact. Extracellular electrodes were fabricated using 0.005- or 0.008-inch-diameter coated silver wire (A-M systems). All electrodes, as well as pump tubing, were held in place by micromanipulators (World Precision Instruments).

Saline was made using a modified Van Harreveld’s solution recipe (44). This was the vehicle for all drugs. EtOH was dissolved in saline to make a 200 mM solution. Previous work in juveniles has used lower concentrations (36), but preliminary experiments showed isolated adult nerve to be more resistant to the effects of EtOH, necessitating a higher concentration. The concentration selected for muscimol was 25 µM, as in previous work by Swierzbinski and Herberholz performed in the MG (41). We used the same concentration of 25 µM for picrotoxin (41), which also matches concentrations used previously on the LG (45, 46). TPMPA solutions were 10 µM. This concentration was selected because it is known to strongly antagonize GABAA-ρ receptors, while having little effect at other GABAA receptors (47). Similarly, a 10 µM concentration of THIP was used because this solution selectively agonizes GABAA-δ receptors (48). Nerve cord lengths of individual preparations were not measured, but statistics on the length of animals and sample sizes used in all experiments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of animal sizes and total number of animals used in neuropharmacology experiments

| Drug | Socialization | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | ISO | 8.58 | 0.57 | 13 |

| Saline | COM | 8.38 | 0.36 | 14 |

| Picrotoxin | ISO | 8.33 | 0.65 | 10 |

| Picrotoxin | COM | 8.10 | 0.34 | 10 |

| TPMPA | ISO | 8.84 | 0.80 | 11 |

| TPMPA | COM | 9.37 | 0.75 | 10 |

| Muscimol | ISO | 8.53 | 0.32 | 8 |

| Muscimol | COM | 8.28 | 0.57 | 11 |

| THIP | ISO | 9.17 | 0.68 | 11 |

| THIP | COM | 9.40 | 0.73 | 11 |

Animal sizes are measured in centimeters from rostrum to telson. COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; THIP, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid.

Experiments were performed in a Faraday cage. All signals were digitized (Digidata 1440; Molecular Devices). Intracellular signals were amplified using a model 900 A intracellular amplifier (Axon Instruments), and extracellular electrode signals were amplified with a model 1700 differential AC amplifier (A-M systems). Extracellular stimulation was applied via a Grass stimulator (Model S88, Natus Medical Inc.) and SIU5 stimulus isolation unit. Axoclamp Commander was used to control extracellular electrodes. Clampex 10.4 was used to record the data. Superfusion inflow was performed via a small tube connected to a Fisher Scientific FH100 peristaltic pump. Flow rate for all drugs was 5 mL/min. All solutions were held in separate aspirator bottles, and changing of solution was performed via electronically controlled solenoid valves.

Baseline measurements were performed with superfusion flow active. Baselines were taken over 15 min. Preparations were then exposed to 30 min of drug (saline, picrotoxin, TPMPA, muscimol, or THIP), followed by 30 min of EtOH, followed by 30 min of saline (“washout”). In all phases of all experiments, the interstimulus interval (ISI) was 90 s to avoid habituation.

Extracellular stimulation voltage (for afferent activation) was adjusted until the LG’s firing threshold was found to be within 0.2 V. The voltage was then reduced to 75% of the threshold voltage, rounded to the nearest 0.2 V. In the rare case that stimulation could not induce an action potential, even at the maximum stimulus of 15 V, the stimulus voltage was used at which the intracellularly recorded PSP showed no further increase with increasing stimulation.

All times were measured relative to the initial voltage change of the stimulus artifact. Both the 3- and 5-ms time points of the PSPs were selected for analysis (Fig. 1B). The 3-ms time point (“early PSP”) was selected, as this coincided with the occurrence of action potentials in our control preparations (mean time: 2.8 ± 1.1 ms), and this time point is known to correspond with the excitatory early β component (29). The 5-ms time point (“late PSP”) was selected, as it corresponds with the later β component, when postexcitatory inhibition (PEI) begins to be a substantial source of input (46). Measurements were taken at the end of each phase (i.e., the PSP size recorded after 30 min of drug, EtOH, or washout).

All measurements were averaged for 100 microseconds (0.1 ms) around the two time points (3 ms and 5 ms) to reduce the effect of transient noise. Some trials were later excluded due to the electrode becoming dislodged from the cell, or other technical reasons. In addition, data were not used if 1) high electrical noise was observed in more than three of the eleven baseline trials, 2) action potentials occurred in the baseline (at 75% threshold level), 3) any of the baseline trials had a PSP size < 0.8 mV, or 4) the coefficient of variation for the preparation’s baseline PSP size was greater than 20%.

pCLAMP (Molecular Devices) software was used to collect data on spiking events after drug application using a threshold search. A trial was marked as having an action potential if a spike occurred before the measurement. To avoid counting the rising phase of a spike as a true PSP measurement, trials were also marked as having action potentials if there was a spike less than 0.5 ms after the time point analyzed. In trials where a spike occurred, the PSP value was replaced with 120% of the PSP value of the most recent trial that was not contaminated by an action potential (49). If action potentials occurred in multiple consecutive trials (which was sometimes the case), we used the same value for all consecutive trials with action potentials.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS (v. 23) or R Statistical Computing v. 3.6.1 (50). The R packages used were broom 0.5.2 (51), plyr 1.8.4 (52), lme4 1.1.21 (53), lmerTest 3.1.0 (54), ggplot2 3.2.1 (55), and ggsignif 0.6.0 (56).

Nonparametric tests were used for behavioral and EtOH hemolymph data. Electrophysiological data were analyzed using a linear mixed model, as this allows for statistical analysis of interactions and has advantages when working with data sets where data may be missing. For this reason, the sample size is sometimes different in different experimental phases, even within a single treatment group.

Linear mixed models attempt to estimate the effect that each variable has on PSP size, compared with another condition (e.g., the effect of picrotoxin compared with the effect of saline exposure in the same group). These estimates are compared statistically to the null hypothesis of a zero effect size. P values are calculated using a two-tailed t test with Satterthwaite’s degrees of freedom approximation.

The models were fit using restricted maximum likelihood. Models included experimental phase, drug condition, and their interaction as fixed effects and included a random intercept for each individual. Both socializations were analyzed together in the primary model. Comparisons were made between all phases and saline baseline, as well as between each phase and its previous phase (e.g., change from muscimol exposure to subsequent EtOH exposure). When analyzing the effect of social experience (ISOs vs. COMs), the model included socialization and its interactions with the other fixed factors. The results consider all other estimates relevant to the specific studied condition. Statistical results are presented in the text, figures, and tables. In all figures, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

RESULTS

Behavior

Using juvenile crayfish, we have previously shown that the biphasic behavioral effects of acute EtOH exposure (i.e., excitation followed by inhibition) are dose dependent (36). Based on these results, we selected a concentration of 2 M EtOH for our current experiments in adult crayfish. Similar to our results in juveniles (36), we found that COMs experienced a significant higher behavioral sensitivity to EtOH compared with ISOs (Fig. 2). The onset of spontaneous tail-flips, a sign of EtOH-evoked excitation, started earlier for COMs (21.6 ± 5.7 min; N = 19) than ISOs (30.1 ± 9.7 min; N = 20), a significant difference (Mann–Whitney U test: P ≤ 0.01). Because we recorded exposure to EtOH for 1 h only, the onset of supine position (“falling on the back”), an indicator of the sedative effects generated by EtOH after longer exposure, was not always observed within this time period. In fact, although 84% (16/19) of COMs dropped on their backs within the hour, only 45% (9/20) of ISOs displayed this behavior. To statistically compare between COMs and ISOs, we assigned a value of 60 min to all cases in which supine position was not observed within the 60-min recording period. Although this may have led to an underestimation of the onset times (mostly for ISOs), we nevertheless found that supine position was observed significantly earlier (Mann–Whitney U test: P < 0.05) for COMs (51.0 ± 7.6 min) than ISOs (56.1 ± 6.8 min). In addition, we analyzed the frequency of supine position within the first hour of intoxication between COMs and ISOs, and the difference was significant [Fisher’s exact test (two sided); P < 0.05]. Thus, prior social experience strongly modulated the behavioral sensitivity to EtOH in adult crayfish as previously described for juvenile crayfish (36).

Figure 2.

Both the onset of tail-flipping behavior (TF) and the onset of supine position (SP) occurred later in adult crayfish that were individually isolated for 1 wk (ISOs) prior to acute 2 M EtOH exposure compared with communally housed crayfish (COMs). Means ± SD are shown. The differences are significant for both behaviors. *P ≤ 0.05. **P ≤ 0.01.

EtOH Concentration in the Hemolymph

Hemolymph (HL) samples were taken and analyzed from COMs and ISOs exposed to 2 M EtOH for 30 min. We found no difference in HL EtOH concentrations between the two social groups (Mann–Whitney U test: P = 0.836; Fig. 3). The average concentration for ISOs (108 ± 24 mmol; N = 6) was almost identical to COMs (109 ± 27 mmol; N = 7). This supports our hypothesis that the differences in behaviors are not based on differences in EtOH uptake or metabolism; instead, the prior social experience shapes the nervous system and alters the neurocellular targets for EtOH.

Figure 3.

Concentration of EtOH in the hemolymph of ISOs and COMs measured immediately after 30-min exposure to 2 M EtOH. Means ± SD are shown. Animals from both groups accumulated substantial amounts of EtOH in their hemolymph, but there was no significant difference in total EtOH concentration. COM, communally housed; HL, hemolymph; ISO, socially isolated.

Since ISO and COM groups contained both males and females, we also analyzed the data with respect to sex-specific differences. Weights and sizes were similar between males (25.69 ± 3.83 g; 9.21 ± 0.41 cm; N = 7; 3 ISOs, 4 COMs) and females (24.90 ± 4.45 g; 9.25 ± 0.59 cm; N = 6; 3 ISOs, 3 COMs), but the HL EtOH concentration was higher in males (121 ± 23 mmol) compared with females (94 ± 18 mmol), a significant difference (Mann–Whitney U test: P = 0.035). The reason for this difference is currently unknown, and measurements of total HL volume and/or EtOH metabolism would be required to determine the underlying mechanism (see discussion).

Neuropharmacology

The results were aggregated across both socializations, and a linear mixed model was used for general comparison. Statistical analyses of various antagonists and agonists were performed controlling for the effects seen in the saline condition. Therefore, P values for all drug measurements indicate whether the change in PSP size (early: 3 ms; late: 5 ms) of the LG is different from the change observed at the same time points in the saline controls. In addition, we compared across socializations (ISOs versus COMs) by controlling for all other factors. See materials and methods for detailed explanation. All means ± SD for all groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

All means and standard deviations for early (3 ms) and late (5 ms) LG PSPs in all groups of animals included in the neuropharmacology experiments

| Saline |

Picrotoxin |

TPMPA |

Muscimol |

THIP |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Socialization | Phase | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| 3 ms | ISO | Baseline | 4.34 | 1.97 | 4.24 | 2.74 | 4.36 | 1.46 | 4.96 | 1.80 | 4.26 | 1.65 |

| 3 ms | ISO | Drug | 4.93 | 2.77 | 4.38 | 3.31 | 4.98 | 1.56 | 4.02 | 2.08 | 4.40 | 1.67 |

| 3 ms | ISO | Ethanol | 6.29 | 3.57 | 5.14 | 4.18 | 5.64 | 1.84 | 5.04 | 2.51 | 4.64 | 2.09 |

| 3 ms | ISO | Washout | 5.50 | 3.98 | 5.31 | 4.01 | 5.26 | 2.06 | 5.09 | 1.94 | 4.97 | 2.04 |

| 3 ms | COM | Baseline | 4.23 | 1.92 | 4.61 | 2.68 | 3.89 | 2.04 | 3.64 | 1.59 | 3.59 | 1.28 |

| 3 ms | COM | Drug | 4.79 | 3.04 | 6.95 | 4.93 | 4.65 | 3.20 | 3.25 | 2.14 | 3.62 | 1.54 |

| 3 ms | COM | Ethanol | 6.01 | 3.35 | 7.57 | 5.00 | 5.59 | 4.66 | 3.75 | 2.11 | 4.37 | 1.83 |

| 3 ms | COM | Washout | 5.62 | 3.23 | 7.46 | 4.46 | 6.05 | 4.66 | 5.12 | 2.36 | 4.56 | 1.64 |

| 5 ms | ISO | Baseline | 3.98 | 1.46 | 4.63 | 2.64 | 3.91 | 1.44 | 4.53 | 1.75 | 5.04 | 1.99 |

| 5 ms | ISO | Drug | 5.15 | 2.02 | 6.22 | 4.87 | 4.69 | 1.51 | 3.59 | 2.07 | 5.22 | 1.83 |

| 5 ms | ISO | Ethanol | 7.39 | 3.13 | 8.01 | 6.66 | 5.69 | 2.01 | 4.84 | 2.71 | 5.81 | 2.30 |

| 5 ms | ISO | Washout | 6.26 | 2.96 | 7.18 | 5.09 | 5.37 | 1.94 | 4.96 | 2.09 | 6.01 | 1.96 |

| 5 ms | COM | Baseline | 4.38 | 1.93 | 4.64 | 1.96 | 3.98 | 2.10 | 4.06 | 1.03 | 4.29 | 1.38 |

| 5 ms | COM | Drug | 4.78 | 2.62 | 8.84 | 4.50 | 4.71 | 3.08 | 3.69 | 2.15 | 4.43 | 1.92 |

| 5 ms | COM | Ethanol | 6.85 | 3.08 | 10.27 | 5.02 | 5.87 | 4.44 | 4.42 | 2.23 | 5.32 | 2.04 |

| 5 ms | COM | Washout | 5.77 | 2.73 | 9.43 | 3.92 | 6.01 | 4.06 | 5.70 | 2.19 | 5.44 | 1.59 |

Values are in millivolts. COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; LG, lateral giant; PSP, postsynaptic potential; THIP, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid.

General effects of EtOH on LG PSP.

To establish control values for the effects of EtOH, we first measured the effects of acute EtOH exposure on the LG PSP after “pretreatment” with crayfish saline (Fig. 4). After 15 min of saline baseline recordings, we superfused saline into the dish for another 30 min. This was followed by superfusion of 200 mM EtOH into the dish for 30 min, and eventually by saline again for 30 min to attempt washout. Throughout the experiment, we recorded LG PSP every 90 s by stimulating the nerves containing primary afferents. Data present the averages of the last three measurements in each phase.

Figure 4.

A: control data (Saline), aggregated across both social conditions. Circles are the linear mixed model’s estimates, and lines are its 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), saline (Sa), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). *P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.001. B: PSP differences observed between ISOs (black) and COMs (gray) in the Saline condition. The circles represent point estimates of the effect that communalization has during saline exposure, controlling for the main effects of saline exposure and phase. Lines are 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), saline (Sa), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). *P ≤ 0.05. COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PSP, postsynaptic potential.

We found that LG PSPs increased during the saline phase compared with baseline for both the early PSP component and late PSP component (Fig. 4A; Table 3). This increase was significant for the late PSP (P ≤ 0.05) and is in line with earlier observations (36, 41), indicating that repeated sensory stimulation can lead to a modest increase in LG excitability over time.

Table 3.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the Saline condition

| 3 ms | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.28 | 4.86 | 6.04 | 5.56 |

| CI | [3.23, 5.33] | [4.29, 5.43] | [5.47, 6.62] | [4.94, 6.18] |

| P (baseline) | 0.051 | 1e-08 | 9e-05 | |

| P (previous) | 0.051 | 1e-04 | 0.138 | |

| 5 ms | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.19 | 4.96 | 7.03 | 6.04 |

| CI | [3.13, 5.25] | [4.27, 5.65] | [6.33, 7.73] | [5.28, 6.79] |

| P (baseline) | 0.033 | 1e-13 | 4e-06 | |

| P (previous) | 0.033 | 4e-08 | 0.012 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

After EtOH exposure, the size of LG PSP increased substantially, and when compared with baseline, the increase was significant for both the early PSP (P ≤ 0.001) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.001). When we compared PSP changes to previous phase, we found significant increases for both the early PSP (P ≤ 0.001) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.001) after application of EtOH. Importantly, this confirms that the facilitation by EtOH was not based on the increase observed after saline in the previous phase. Thus, EtOH facilitated LG PSP as we have reported before in recordings from semi-intact juveniles, strongly suggesting that EtOH’s stimulating effects persist even in the absence of brain-derived tonic inhibition. The observed EtOH-induced facilitation was reduced during washout, but PSPs remained higher when compared with baseline, and only the late PSP was significantly suppressed when compared with the previous EtOH phase (P ≤ 0.05). This is in line with prior results showing resilience to EtOH washout in the LG neuron even after 60 min of saline application (36).

Next, we compared socially experienced (COMs) and socially deprived (ISOs) groups of crayfish (Fig. 4B; Table 4). Baselines for the early PSP were similar between the two groups, and we did not find any difference between the two groups after exposure to saline. In addition, there were no differences after exposure to EtOH, or during washout. A similar picture emerged for the late PSP component. Baselines for the late PSP were similar between the two groups, and we did not find any difference between the two groups after exposure to saline or EtOH. During washout, however, the late PSP was reduced significantly more in COMs compared with ISOs (P ≤ 0.05).When compared with previous phases, we did not find any significant changes of early or late LG PSPs.

Table 4.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the two social groups in the Saline condition

| 3 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.34 | 4.93 | 6.29 | 5.98 |

| CI | [2.85, 5.82] | [4.14, 5.72] | [5.5, 7.08] | [5.12, 6.84] |

| 3 ms (COMs) | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.23 | 4.79 | 5.8 | 5.18 |

| CI | [2.16, 6.29] | [3.7, 5.89] | [4.69, 6.91] | [3.98, 6.37] |

| P (baseline) | 0.954 | 0.525 | 0.277 | |

| P (previous) | 0.954 | 0.563 | 0.62 | |

| 5 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.98 | 5.15 | 7.39 | 6.64 |

| CI | [2.48, 5.48] | [4.19, 6.12] | [6.43, 8.36] | [5.58, 7.69] |

| 5 ms (COMs) | Baseline | Saline | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.38 | 4.78 | 6.67 | 5.48 |

| CI | [2.29, 6.47] | [3.44, 6.12] | [5.31, 8.02] | [4.01, 6.94] |

| P (baseline) | 0.281 | 0.123 | 0.047 | |

| P (previous) | 0.281 | 0.631 | 0.577 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated. P values of < 0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

Overall, this analysis failed to show any major differences in sensitivity to EtOH between ISOs and COMs. This result is different from earlier work in semi-intact juvenile crayfish showing that EtOH sensitivity depends on prior social experience (36). It therefore suggests that the socially mediated responses of the LG to EtOH might be related to intact, brain-derived tonic inhibition in those semi-intact preparations.

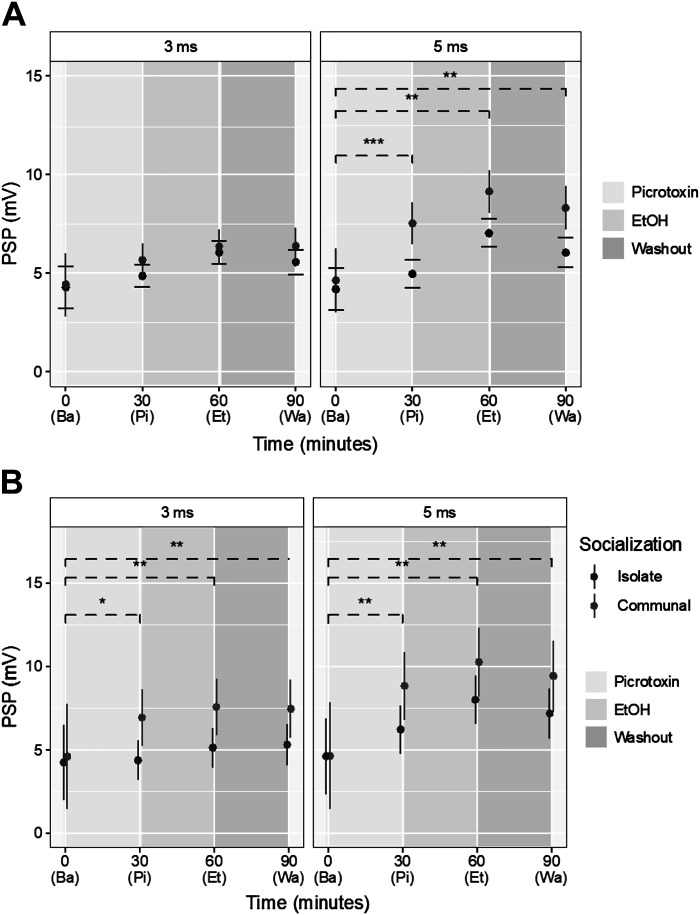

Effects of GABAA receptor antagonists.

Next, we measured the effects of acute EtOH exposure on the LG PSP after pretreatment with picrotoxin (PTX), a GABAA receptor antagonist (Fig. 5). After 15 min of saline baseline recordings, the isolated nerve cord was superfused with PTX for 30 min, followed by superfusion of 200 mM EtOH for 30 min, and washout with saline for 30 min. The results were compared with the saline “control” condition described above.

Figure 5.

A: effects of PTX aggregated across social conditions. Circles are the linear mixed model’s estimates, and lines are its 95% confidence interval. Black circles and lines are the estimates and confidence intervals for the saline condition, presented here for comparison. Significance brackets are broken to emphasize that comparisons are between the changes seen in drug and saline control conditions, rather than directly between phases. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), picrotoxin (Pi), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. B: PSP differences observed between ISOs (black) and COMs (gray) in the PTX condition. The circles represent point estimates of the effect of communalization, controlling for the main effects of PTX exposure and phase. Lines are 95% confidence intervals. Significance brackets are broken to emphasize that comparisons are between the changes seen in PTX and saline control conditions, rather than directly between phases. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), picrotoxin (Pi), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01. COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PSP, postsynaptic potential; PTX, picrotoxin.

We found that LG PSPs increased during the PTX phase compared with baseline for both the early PSP component and late PSP component (Fig. 5A; Table 5). The increase over saline was significant only for the late component (P ≤ 0.001). In EtOH, the LG PSP increased further, and the increase was significant for the late component when compared with baseline. During washout, the LG PSPs remained higher compared with saline, but the difference was only significant when compared with baseline. In summary, PTX produced a stronger facilitation of the late LG PSP component when compared with saline control, whereas the early component was largely unaffected.

Table 5.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the PTX condition

| 3 ms | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.43 | 5.66 | 6.35 | 6.38 |

| CI | [2.81, 6.04] | [4.79, 6.53] | [5.48, 7.23] | [5.48, 7.28] |

| P (baseline) | 0.147 | 0.716 | 0.154 | |

| P (previous) | 0.147 | 0.281 | 0.283 | |

| 5 ms | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.64 | 7.53 | 9.14 | 8.31 |

| CI | [3.01, 6.26] | [6.47, 8.59] | [8.07, 10.2] | [7.2, 9.41] |

| P (baseline) | 2e-04 | 3e-03 | 2e-03 | |

| P (previous) | 2e-04 | 0.41 | 0.777 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; PTX, picrotoxin. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

Interestingly, when we compared ISOs and COMs, we found some striking differences (Fig. 5B; Table 6). Compared with saline, the LG PSP was much more facilitated by PTX in COMs compared with ISOs. This was true for the early (P ≤ 0.05) and late PSP component (P ≤ 0.01). Moreover, when compared with baseline, the LG PSP after EtOH was significantly higher in COMs for the early (P ≤ 0.01) and late PSP component (P ≤ 0.01). These differences between ISOs and COMs were maintained in washout; the early PSP (P ≤ 0.01) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.01) were higher in COMs than ISOs.

Table 6.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the two social groups in the PTX condition

| 3 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.24 | 4.38 | 5.14 | 5.31 |

| CI | [1.99, 6.5] | [3.18, 5.57] | [3.94, 6.33] | [4.06, 6.55] |

| 3 ms (COMs) | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.61 | 6.95 | 7.57 | 7.46 |

| CI | [1.44, 7.77] | [5.27, 8.63] | [5.88, 9.26] | [5.71, 9.2] |

| P (baseline) | 0.013 | 7e-03 | 8e-03 | |

| P (previous) | 0.013 | 0.815 | 0.973 | |

| 5 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.63 | 6.22 | 8.01 | 7.18 |

| CI | [2.35, 6.91] | [4.75, 7.68] | [6.54, 9.47] | [5.66, 8.71] |

| 5 ms (COMs) | Baseline | PTX | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.64 | 8.84 | 10.27 | 9.43 |

| CI | [1.45, 7.84] | [6.78, 10.89] | [8.2, 12.33] | [7.29, 11.56] |

| P (baseline) | 2e-03 | 2e-03 | 1e-03 | |

| P (previous) | 2e-03 | 0.993 | 0.712 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PTX, picrotoxin. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

This result indicates a strong socially mediated effect of the GABAA-receptor antagonist PTX. The LG PSPs of COMs were much more affected by PTX, which also led to changes in the responses to EtOH, and the effect remained during washout. This was observed for both the early and late LG PSP component.

Next, we measured the effects of acute EtOH exposure on the LG PSP after pretreatment with TPMPA, a GABAA receptor antagonist for receptors containing ρ (rho) subunits (Fig. 6). After 15 min of baseline recordings, the isolated nerve cord was superfused with TPMPA for 30 min, followed by superfusion of 200 mM EtOH for 30 min, and washout with saline for 30 min. The results were compared with the saline control condition as described above.

Figure 6.

A: effects of TPMPA aggregated across social conditions. Circles are the linear mixed model’s estimates, and lines are its 95% confidence interval. Black circles and lines are the estimates and confidence intervals for the saline condition, presented here for comparison. Significance brackets are broken to emphasize that comparisons are between the changes seen in drug and saline control conditions, rather than directly between phases. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), TPMPA (TP), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). B: PSP differences observed between ISOs (black) and COMs (gray) in the TPMPA condition. The circles represent point estimates of the effect of communalization, controlling for the main effects of TPMPA exposure and phase. Lines are 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), TPMPA (TP), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PSP, postsynaptic potential; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid.

Overall, the GABAA-ρ antagonist TPMPA did not have a major effect on the LG PSP when compared with the saline condition (Fig. 6A; Table 7). We found no significant differences for the drug itself, EtOH, or during washout for both the early and late PSP components.

Table 7.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the TPMPA condition

| 3 ms | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.13 | 4.82 | 5.65 | 5.47 |

| CI | [2.54, 5.72] | [3.96, 5.68] | [4.78, 6.52] | [4.56, 6.38] |

| P (baseline) | 0.805 | 0.594 | 0.906 | |

| P (previous) | 0.805 | 0.437 | 0.531 | |

| 5 ms | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.94 | 4.69 | 5.77 | 5.47 |

| CI | [2.34, 5.54] | [3.65, 5.74] | [4.71, 6.84] | [4.37, 6.58] |

| P (baseline) | 0.972 | 0.07 | 0.586 | |

| P (previous) | 0.972 | 0.075 | 0.234 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid.

When we compared ISOs and COMs, we also found no differences (Fig. 6B; Table 8). Thus, unlike PTX, TPMPA was ineffective in modulating the LG PSP, and only the late PSP showed a modest interaction with EtOH. Moreover, there were no effects related to socialization, suggesting that GABAA-ρ receptors might not be present in the LG circuit of crayfish (see discussion).

Table 8.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the two social groups in the TPMPA condition

| 3 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.36 | 4.98 | 5.7 | 5.32 |

| CI | [2.16, 6.55] | [3.82, 6.15] | [4.51, 6.88] | [4.08, 6.55] |

| 3 ms (COMs) | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.89 | 4.65 | 5.59 | 5.64 |

| CI | [0.76, 7.01] | [2.99, 6.3] | [3.91, 7.27] | [3.88, 7.39] |

| P (baseline) | 0.849 | 0.407 | 0.114 | |

| P (previous) | 0.849 | 0.521 | 0.431 | |

| 5 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.91 | 4.69 | 5.68 | 5.36 |

| CI | [1.69, 6.13] | [3.26, 6.11] | [4.23, 7.13] | [3.84, 6.87] |

| 5 ms (COMs) | Baseline | TPMPA | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.98 | 4.71 | 5.87 | 5.6 |

| CI | [0.83, 7.13] | [2.68, 6.73] | [3.81, 7.93] | [3.45, 7.75] |

| P (baseline) | 0.505 | 0.261 | 0.133 | |

| P (previous) | 0.505 | 0.64 | 0.671 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid.

Effects of GABAA receptor agonists.

When we tested the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (Fig. 7), we found that muscimol significantly attenuated both the early (P ≤ 0.01) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.05) relative to baseline (Fig. 7A; Table 9). In preparations treated with muscimol, the facilitation caused by EtOH was also reduced, and this suppression was significant for the early (P ≤ 0.001) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.001). When we compared changes in PSPs to the previous phase, we found that muscimol only reduced the late LG PSP after EtOH exposure (P ≤ 0.05), and both the early (P ≤ 0.05) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.01) were significantly less suppressed in washout.

Figure 7.

A: effects of muscimol aggregated across social conditions. Circles are the linear mixed model’s estimates, and lines are its 95% confidence interval. Black circles and lines are the estimates and confidence intervals for the saline condition, presented here for comparison. Significance brackets are broken to emphasize that comparisons are between the changes seen in drug and saline conditions, rather than directly between phases. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), muscimol (Mu), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa).*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. B: PSP differences observed between ISOs (black) and COMs (gray) in the muscimol condition. The circles represent point estimates of the effect of communalization, controlling for the main effects of muscimol exposure and phase. Lines are 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), muscimol (Mu), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). *= P ≤ 0.05. COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PSP, postsynaptic potential.

Table 9.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the muscimol condition

| 3 ms | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.2 | 3.57 | 4.29 | 4.99 |

| CI | [2.56, 5.83] | [2.69, 4.45] | [3.4, 5.18] | [4.06, 5.91] |

| P (baseline) | 9e-03 | 4e-04 | 0.308 | |

| P (previous) | 9e-03 | 0.315 | 0.015 | |

| 5 ms | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.26 | 3.65 | 4.6 | 5.27 |

| CI | [2.61, 5.91] | [2.57, 4.73] | [3.52, 5.68] | [4.14, 6.4] |

| P (baseline) | 0.015 | 1e-05 | 0.157 | |

| P (previous) | 0.015 | 0.048 | 5e-03 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

Together, this suggests that muscimol is an effective inhibitor of the LG PSPs, resulting in a decrease in early and late PSP sizes. While EtOH still caused a modest increase of PSP sizes, pretreatment with muscimol reduced the magnitude of the increase when compared with baselines. However, when compared with previous phase, this suppression of EtOH effects was only observed for the late PSP, suggesting that, for the early PSP, it was likely based on the general suppression of the LG PSP by muscimol before EtOH was applied. Washout of EtOH resulted in an increase in PSP sizes rather than the decrease seen in saline controls. Washout of muscimol probably contributed to this effect, which would increase PSP sizes.

When we compared ISOs and COMs (Fig. 7B; Table 10), we found no significant differences between the two groups other than a less effective washout in COMs that was significant for the late PSP when compared with baseline (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 10.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the two social groups in the muscimol condition

| 3 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.96 | 4.02 | 5.04 | 5.09 |

| CI | [2.55, 7.37] | [2.74, 5.3] | [3.76, 6.32] | [3.76, 6.41] |

| 3 ms (COMs) | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.64 | 3.25 | 3.75 | 4.95 |

| CI | [0.4, 6.88] | [1.53, 4.96] | [2.02, 5.47] | [3.15, 6.74] |

| P (baseline) | 0.524 | 0.658 | 0.051 | |

| P (previous) | 0.524 | 0.849 | 0.127 | |

| 5 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.53 | 3.59 | 4.84 | 4.96 |

| CI | [2.1, 6.96] | [2.03, 5.16] | [3.28, 6.41] | [3.34, 6.58] |

| 5 ms (COMs) | Baseline | Muscimol | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.06 | 3.69 | 4.42 | 5.53 |

| CI | [0.79, 7.33] | [1.59, 5.79] | [2.31, 6.53] | [3.34, 7.73] |

| P (baseline) | 0.233 | 0.303 | 0.027 | |

| P (previous) | 0.233 | 0.876 | 0.222 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

Next, we measured the effects of the drug THIP, which agonizes GABAA-receptor with the δ (delta) subunit (Fig. 8). When compared with baseline, the agonist reduced the facilitation of the LG PSP normally seen after EtOH in the saline controls, and this was significant for the early PSP (P ≤ 0.01) and late PSP (P ≤ 0.001), similar to what we observed with muscimol. It also decreased the late PSP during EtOH when compared with the previous THIP phase (P ≤ 0.01), similar to muscimol, but no significant changes were found during washout (Fig. 8A; Table 11).

Figure 8.

A: effects of THIP aggregated across social conditions. Circles are the linear mixed model’s estimates, and lines are its 95% confidence interval. Black circles and lines are the estimates and confidence intervals for the saline condition, presented here for comparison. Significance brackets are broken to emphasize that comparisons are between the changes seen in drug and saline conditions, rather than directly between phases. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), THIP (TH), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. B: PSP differences observed between ISOs (black) and COMs (gray) in the THIP condition. The circles represent point estimates of the effect of communalization, controlling for the main effects of THIP exposure and phase. Lines are 95% confidence intervals. The x-axis is shaded based on the solution being superfused at each time. Time points correspond to the end of baseline (Ba), THIP (TH), EtOH (Et), and washout (Wa). COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; PSP, postsynaptic potential; THIP, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol.

Table 11.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the THIP condition

| 3 ms | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.93 | 4.01 | 4.4 | 4.58 |

| CI | [2.36, 5.5] | [3.16, 4.86] | [3.55, 5.26] | [3.68, 5.48] |

| P (baseline) | 0.262 | 4e-03 | 0.178 | |

| P (previous) | 0.262 | 0.079 | 0.164 | |

| 5 ms | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.66 | 4.83 | 5.47 | 5.53 |

| CI | [3.08, 6.24] | [3.79, 5.86] | [4.42, 6.51] | [4.44, 6.63] |

| P (baseline) | 0.258 | 2e-04 | 0.088 | |

| P (previous) | 0.258 | 9e-03 | 0.065 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; THIP, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol. P values of <0.05 are presented in bold typeface.

When we compared ISOs and COMs after THIP treatment, we found no significant differences between the two groups for the drug phase, EtOH, or washout (Fig. 8B; Table 12). This suggests no differences in GABAA-δ receptors between ISOs and COMs, either in expression or function. Nonetheless, the overall result strongly indicates that the crayfish LG circuit contains GABAA-δ receptors, an important, new finding for the crayfish nervous system.

Table 12.

Linear mixed model’s estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and P values for the two social groups in the THIP condition

| 3 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.26 | 4.4 | 4.64 | 4.79 |

| CI | [2.07, 6.46] | [3.24, 5.57] | [3.47, 5.8] | [3.55, 6.03] |

| 3 ms (COMs) | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 3.59 | 3.62 | 4.18 | 4.37 |

| CI | [0.51, 6.67] | [1.98, 5.25] | [2.52, 5.84] | [2.64, 6.1] |

| P (baseline) | 0.929 | 0.506 | 0.305 | |

| P (previous) | 0.929 | 0.452 | 0.699 | |

| 5 ms (ISOs) | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 5.04 | 5.22 | 5.81 | 5.84 |

| CI | [2.82, 7.25] | [3.79, 6.65] | [4.39, 7.24] | [4.32, 7.35] |

| 5 ms (COMs) | Baseline | THIP | Ethanol | Washout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 4.29 | 4.43 | 5.11 | 5.23 |

| CI | [1.18, 7.4] | [2.43, 6.43] | [3.08, 7.15] | [3.11, 7.35] |

| P (baseline) | 0.497 | 0.284 | 0.135 | |

| P (previous) | 0.497 | 0.687 | 0.64 |

Comparisons of all phases to baseline and to each previous phase are shown. CI, confidence interval; COM, communally housed; ISO, socially isolated; THIP, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo(5,4-c)pyridin-3-ol.

DISCUSSION

Behavior

We found that freely behaving adult crayfish respond to acute EtOH exposure very similar to crayfish juveniles (36). The stereotypic nature of the behavioral changes elicited by acute EtOH exposure is remarkable. The biphasic effects caused by increasing EtOH intoxication are demonstrated by spontaneous tail-flips at the early stages of exposure that signifies the excitatory (or disinhibitory) actions of EtOH, and by supine position, the loss of motor control, at the later stages of exposure via its strong inhibitory effects. Thus, adult crayfish, much like other animals, including humans, are behaviorally sensitive to EtOH and display robust, quantifiable responses when intoxicated.

In line with our previously published results in juvenile crayfish (36), prior social experience had a profound effect on the behavioral responses to EtOH. Communally housed animals (COMs) were more strongly affected by EtOH than animals that were socially isolated for 1 wk (ISOs) before exposure to EtOH. Thus, the effects of social history on behavioral sensitivity to EtOH generalizes across the lifespan of crayfish, with social experience being a common predictor of alcohol sensitivity in these animals.

We demonstrated previously that the EtOH-evoked behavioral effects are dose dependent in juvenile crayfish (36). Using EtOH concentrations of 0.1 M, 0.5 M, or 1 M, we described a strong correlation between drug concentration and onset of tail-flipping and supine position, confirming that higher EtOH concentrations lead to faster intoxication. Because low drug concentrations required hours of observation before behavioral effects were detected, and not all animals expressed the behaviors, we eventually settled on 1 M EtOH as the external concentration for comparison of the social groups (36). In the current study, we doubled the highest bath concentration of EtOH (i.e., 2 M) and elicited the behavioral changes in adult crayfish at roughly the same time points after EtOH exposure began. Since our adults were more than twice the size and weight of the previously used juveniles, this might suggest that adult crayfish are more sensitive to the intoxicating effects of EtOH. Previous studies in rodents also reported more resistance and less impaired motor function in EtOH-exposed adolescent rats compared with adults (57–59). Other studies using a memory task in rodents and humans, however, reported higher vulnerability to the effects of acute EtOH during adolescence (60, 61). Additional studies are required in crayfish of various developmental stages to gain further evidence for age-related effects.

EtOH Concentrations in the Hemolymph

We also measured EtOH concentrations in the hemolymph of intoxicated ISOs and COMs. We found that they did not differ, which strongly suggests that the observed behavioral differences are not based on differences in EtOH uptake or metabolism but are linked to changes in the nervous system that result from prior social experiences. This supports our notion that social environment shapes the nervous system and modifies the neurocellular targets for EtOH (36, 41). The values we measured for hemolymph EtOH concentrations are similar to what has been reported in crayfish before (31–33). Similar to these earlier studies, we found ∼5% of the external concentration (i.e., ∼100 mM) in the hemolymph after 30 min of acute EtOH exposure. Contrary to mammals, and especially humans, these concentrations did not induce major motor impairments or death in crayfish, which will only occur if exposure to EtOH continues for much longer (Herberholz, unpublished observation). Interestingly, other invertebrates like honeybees and fruit flies also seem to be able to tolerate higher EtOH concentrations than mammals (e.g., 62, 63).

Somewhat surprisingly, we also found higher EtOH concentrations in the hemolymph of males compared with females. Our sample size was small, and this result needs further confirmation, but it might suggest a difference in uptake or metabolism between both sexes. Notably, it has been shown that females have faster elimination rates for EtOH than males across a variety of species, including rats, macaque monkeys, and humans (64–66). Our future work could be aimed at investigating the mechanisms of EtOH metabolism in crayfish as well as any behavioral differences exhibited by adult male and female crayfish after acute EtOH exposure. This was not possible in our current study where only male crayfish were used in behavioral experiments.

Future investigation could also measure possible effects of different molt stages, which shape escape behavior and related circuitry through the actions of steroid hormones in crustaceans (67–70).

Neuropharmacology

We found that acute EtOH facilitated the LG PSP in the isolated nerve cord of adult crayfish. This confirms our previous findings that EtOH increases PSPs of the crayfish giant escape neurons (36), including the MG neurons, which are located in the brain (41). These earlier studies used preparations with intact tonic inhibition, and differences between socially isolated and communally housed crayfish were readily detectable (36). This result was not replicated in our current study, suggesting that the interactions between EtOH and social experience might depend on brain-derived tonic inhibition in the escape circuits. For example, EtOH has been shown to augment tonic inhibitory currents in rodents (71–73), but in our experiments on the isolated abdominal nerve cord, the natural ligand (GABA) for tonic inhibition was not present.

Washout of EtOH was more effective in COMs. This confirms prior results showing that washout of various drugs is easier to obtain in neurons of socially experienced crayfish compared with socially isolated ones, including EtOH and serotonin (36, 74). The reason for this has not been determined, but it suggest an interesting effect that depends on social experience, and it may provide COMs, which live in groups and face rapidly changing social situations, with the advantage of increased neuronal and behavioral plasticity (see below).

Picrotoxin (PTX) itself caused a significant facilitation of the PSP, and pretreatment with PTX caused an additional increase of the late PSP after EtOH application. However, this was only observed when the changes in PSP were compared with saline baseline, not to the previous phase (i.e., EtOH after PTX), suggesting that the facilitation of the PSP was mostly due to the actions of the GABAA-receptor antagonist, not EtOH. Since PTX is a very potent antagonist, which binds within the pore of chloride channels, this mechanism likely prevented EtOH from modulating these channels. Thus, the increase in PSPs seen after EtOH exposure alone is likely to involve other neurotransmitter systems. PTX is also a notoriously difficult drug to wash out (e.g., 39, 45), so the absence of an effective reversal in the washout phase is unsurprising.

Importantly, we found that PTX had a much stronger effect in COMs than ISOs, and the observed PTX effect occurred at both the early (3 ms) and late (5 ms) LG PSP. Since tonic inhibition was removed in our study, this result suggests that the differences between COMs and ISOs are based on differences in synaptic GABAA receptors that are present in the LG circuit and presumably on the LG dendrites (75). A difference in GABA receptor distribution and function between communally housed and social isolated crayfish has not been reported before, and this opens up interesting avenues for future investigation. Moreover, previous research suggested that PTX has little effect on the early PSP and instead blocks postexcitatory inhibition that occurs >4 ms after stimulus onset (46); however, this research was performed with individually housed (i.e., isolated) crayfish only, which might explain the differences between the two studies. The purpose for the delayed postexcitatory inhibition is to sharpen the LG’s response to sensory inputs, as it prevents responses to slower, more gradual stimuli (46). At 3 ms of the PSP (after stimulus onset), spikes are generally produced if the input is strong and phasic, and thus any inhibition around this time would be more effective in regulating LG threshold by balancing simultaneous excitatory inputs. Together this suggests intriguing differences in synaptic GABAergic inhibition between COMs and ISOs.

PTX also binds to chloride channels that are gated by other neurotransmitters besides GABA (76), and we recently found preliminary evidence that LG’s recurrent inhibition (which prevents it from firing another action potential during tail-flip escape) is mediated—at least in part—by glutamate-gated chloride channels (Venuti & Herberholz, unpublished observations). In addition, high concentrations of PTX have been shown to antagonize postsynaptic acetylcholine responses (e.g., 77), and cholinergic transmission is critical for excitation of LG via the chemical synapse in the circuit between primary afferents and interneurons (78). The concentration of PTX in our experiments (25 μM) increased over time due to superfusion into the dish, and we found that the social differences appeared early in our experiments when concentrations were still low (data not shown). Nonetheless, it should be acknowledged that the social differences we observed in response to PTX might not be based on GABAergic mechanisms alone.

What could be the adaptive function of COMs exhibiting more synaptic inhibition? Although additional data are needed to answer this question, a couple of interesting hypotheses can be proposed: COMs live in groups and are likely to receive frequent nonthreatening inputs to their abdomens due to their conspecifics nearby. Crayfish are known to form dominance hierarchies when housed in groups or pairs, and both attacks and escapes are reduced once hierarchies are formed and stabilized (e.g., 79–81). In addition, although not tested in crayfish specifically, living within a group reduces the danger of predation (“safety in numbers”), as has been demonstrated for various species (e.g., 82). Thus, increased inhibition and the corresponding higher threshold for escape might be an adaptation to communal living in crayfish. This is further supported by studies in cichlid fish that reported lower threat sensitivity in groups of fish compared with isolates (83). Moreover, we recently found that prior housing conditions affected the responses to simulated predator attacks in juvenile crayfish. Crayfish isolated for 1 wk before testing exhibited a much higher frequency of escape tail-flips, mediated by the medial giant (MG) interneuron, compared with animals that had unlimited access to sensory signals from conspecifics during the 1 wk before predator exposure (84).

TPMPA, an antagonist selective for GABAA-ρ receptors did not have any appreciable effect in our study, nor did it interact with EtOH or differ depending on social experience. This may suggest a lack of GABAA-ρ receptors in the LG circuit. However, the preparations used in our experiments did not experience tonic, brain-derived inhibition, therefore lacking the natural ligand and its actions that TPMPA would normally antagonize. GABAA-ρ receptors are involved in tonic inhibition of mammalian neurons (85), and their existence in crustacean nervous systems has been suggested by pharmacological and genetic studies (86, 87). Although we found no evidence for GABAA-ρ receptors, this result does not preclude the possibility that they exist in the LG circuit or elsewhere in the crayfish nervous system (41).

Muscimol significantly suppressed the LG PSPs, as is expected of a potent GABAA agonist. In addition, the facilitatory effects of EtOH were reduced in preparations pretreated with muscimol compared with saline controls. This could be due to the general inhibition evoked by muscimol, which may have counterbalanced the excitatory effects of EtOH or synergistic interaction between the two drugs. As mentioned earlier, EtOH is known to potentiate GABA receptors (acting as an indirect agonist; i.e., positive allosteric modulator) so that receptor responses to ligands are increased in magnitude (e.g., 88–90). EtOH may thus have increased inhibition itself by amplifying the actions of GABA and/or muscimol.

Whether muscimol produced its effects by binding to synaptic and/or extrasynaptic receptors is unknown at this point, but since its interplay with socialization was subtle and limited to washout after EtOH application, a strong interaction with tonic inhibitory receptors seems less likely (see below). This is consistent with previous work on the MG neuron of socially isolated crayfish with intact tonic inhibition. Here too, we found that muscimol suppressed the facilitatory effects of EtOH (41), suggesting that the interaction between muscimol and EtOH is largely independent of tonic inhibitory mechanisms. However, in our previous investigation of the MG neuron, muscimol itself did not reduce MG PSPs, while this was the case in the current study for LG PSPs. Although this might indicate some differences in the actions of muscimol on these two escape neurons, or on tonic GABAergic receptors, the study on MG neurons was restricted to socially isolated animals only. In our current study, we did not observe any significant differences between ISOs and COMs, and thus the mechanism underlying this difference requires further investigation.

Our finding that early and late LG PSP increased after washout indicate that both the inhibitory ligand and its allosteric modulator (EtOH) were successfully removed from the GABA receptors. A slightly stronger effect in COMs might suggest that more receptors were affected in COMs. This mirrors the effect seen with serotonin and EtOH (36, 74).

THIP, a highly selective agonist for GABAA-δ receptors, reduced the efficacy of EtOH to facilitate the LG PSPs, similar to the effects observed with muscimol. It is known that GABAA-δ receptors are potentiated by EtOH (e.g., 12), and therefore it seems likely that the effect observed in our study is due to this interaction. This would imply that GABAA-δ-like receptors are present in the crayfish LG circuit, a new finding that has not been reported before.

Outside its interaction with EtOH, the effect of THIP on the LG PSP was subtle, but it was readily apparent with muscimol, which substantially reduced LG PSPs. GABAA-δ receptors are typically located extrasynaptically and primarily mediate tonic inhibition (e.g., 91), and it is possible that muscimol acted on a wider range of receptors, including synaptic ones. Eliminating tonic inhibition in the LG circuit by blocking brain-derived descending inputs produced only a small increase of LG PSP size (38), which is in line with our finding that activating putative tonic receptors with THIP has only minor effects. Moreover, previous studies have shown that THIP is much less potent in inhibiting neural firing than muscimol (e.g., 92, 93), and experiments performed on the crayfish stretch receptors with higher THIP concentration than we used failed to show any effect (94, 95). A more specific test of the presence of open channels, such as membrane conductance measurements, would be a future approach to understand the role of THIP on the excitability of LG.

Despite this, our finding that THIP reduced the facilitatory effects of EtOH on LG PSPs, especially the late component, is significant and in line with previous work on this receptor (e.g., 71). Our result, obtained in preparation where the natural ligand for tonic inhibition was removed, suggests that THIP likely acted on GABAA-δ-like receptors that are present on the LG neuron. It further suggests that this inhibition was potentiated by EtOH.

We found no social differences in response to THIP in our current study. Previously, we showed that blocking tonic inhibition in semi-intact juvenile crayfish eliminated the differences between COMs and ISOs in their response to low concentrations of EtOH (36). This suggested that tonic inhibition is related to the socially mediated changes in EtOH sensitivity. The lack of interactions between socialization, THIP, and EtOH, however, supports the idea that such changes are not based on differences in expression of GABAA-δ-like receptors but are more likely caused by differences in release patterns of brain-derived GABA. Molecular and/or immunohistochemical investigations of receptor content and distribution would be a fruitful approach for testing this hypothesis.