Abstract

Objectives:

Drug reference databases provide information on potential drug-related medical complications in a dental patient. It is important that database entries and recommendations are supported by evidence-based original studies focused on drug-related dental management complications. The aim of this study was to review and identify database drug categories associated with evidence-based drug-related medical complications during dental treatment

Data Sources:

Relevant publications on adverse drug reactions and dental management complications were thoroughly reviewed from the literature published between July 1975 and July 2019.

Material and Methods.

We reviewed the drug reference database ‘Lexicomp online for dentistry’ to identify medications associated with highest propensity to trigger drug-related dental management complications and correlated these with published original studies in PubMed®, EMBASE®, and Scopus® databases that associated drug actions with dental treatment complications.

Results:

Fifty-four publications (1.2% of all full text articles) reported original studies that directly tested drug associations with dental management complications. The cautions in the drug reference database on drug-related dental treatment mainly focused on local anesthetic precaution (p<0.001), xerostomia (p<0.001), bleeding (p<0.001) and a combination of xerostomia and bleeding (p<0.001). Antipsychotics/antidepressants were mostly associated with local anesthetic complications (80.95%), xerostomia (81.93%) and a combination of xerostomia and bleeding (22.89%). Bleeding complication was associated with anticoagulants (80%) and cancer chemotherapeutic agents (59.21%).

Conclusions:

Similarities exist within and across different drug categories in the database entries on drug-related medical complications in a dental patient. There was a relatively limited number of publications that directly tested the association between drug-related medical complications and dental therapies.

Practical implications:

The most common drug cautions during dental treatment reported in ‘Lexicomp online for dentistry’ were limited to drug-drug interactions with local anesthetic actions, excessive bleeding, xerostomia or a combination of any of these. These recommendations were supported by limited evidence-based studies.

Keywords: Drugs effects, Medical complications, Xerostomia, Bleeding, Dental treatment planning

Introduction

The characteristics of patients treated by the dental healthcare provider continue to evolve as humans live longer and many previously fatal medical conditions can now be safely treated because of advances in the medical sciences. Hence, there is greater likelihood that a dental patient will present with a pre-existing major and/or chronic medical condition 1 and many patients may also be on multiple medications that can potentially cause adverse drug reactions 2–4. It is paramount that the dental healthcare provider is aware of a patient’s medical status and medication history before formulating and implementing a comprehensive treatment plan. Hence, the overall healthcare needs of the patient can be addressed, and medical emergencies can be avoided. Majority of medical emergencies and risks of adverse events in a dental patient are often linked to bleeding, infections, drug actions and interactions as well as patient’s ability to withstand stress and trauma of dental treatment 5. It is the responsibility of the dental practitioner to prevent any life-threatening adverse event in the dental office, so complete review of the patient’s medical history is the basic starting point to know the patients’ medical condition. In addition, it is standard practice to document the patient’s medications and check various drug reference manuals for relevant information on adverse drug effects that may require modifying dental treatment plan based on the patient’s health status 6,7.

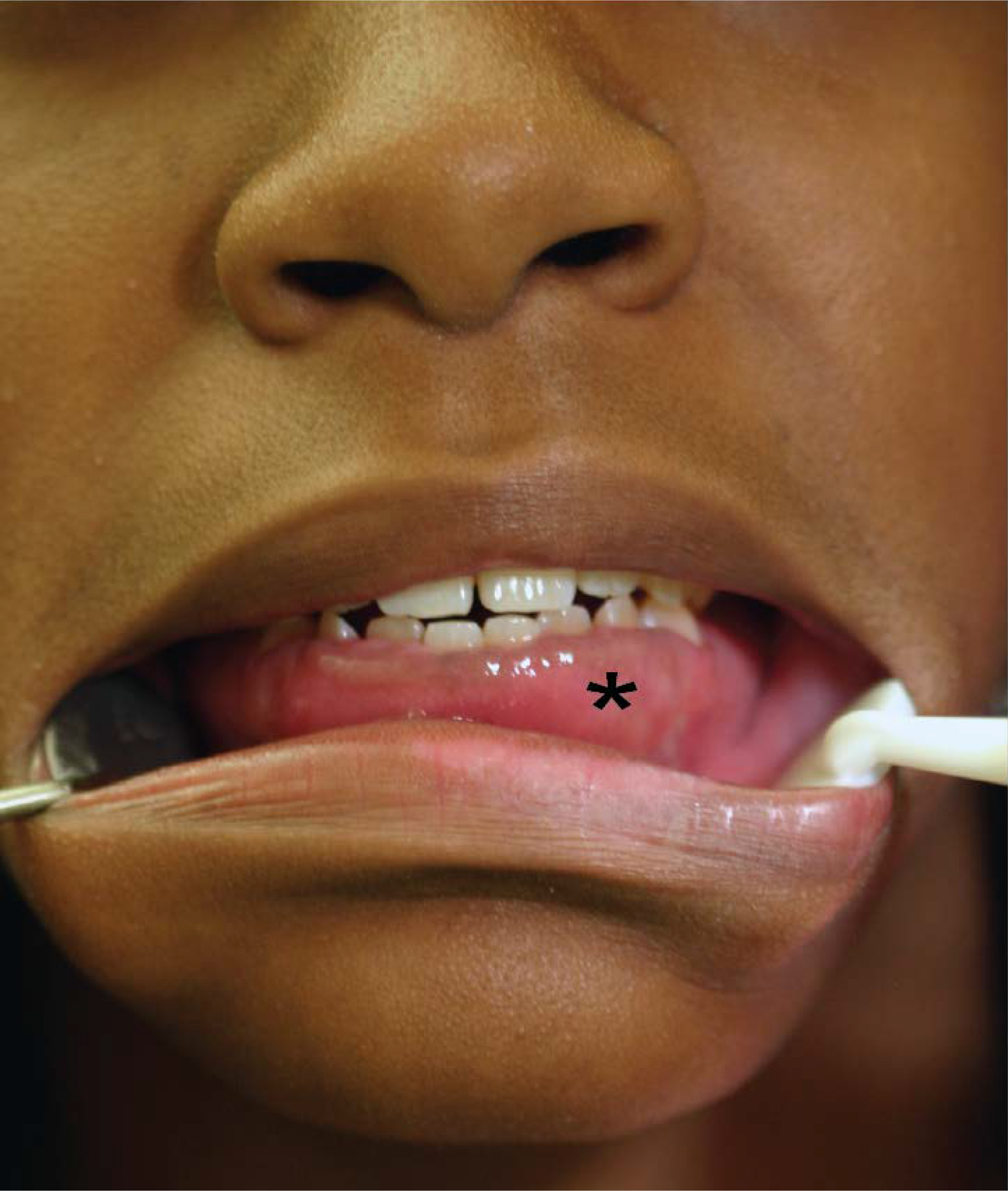

Several examples underscore the significance of consulting drug reference manuals. A patient on long-term use of bone anti-resorptives like bisphosphonates and denosumab is prone to jaw osteonecrosis 8,9, so dental extractions may need to be delayed or avoided if possible 10,11. When a hypertensive patient is on concomitant treatment for pain with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the clinician needs to exercise caution because NSAIDs can reduce the effectiveness of antihypertensive drugs such as beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and diuretics if taken for more than one week 12. Additionally, when the patient’s physician switches the patient to calcium channel blockers, there is a high risk of the complication of gingival hyperplasia in some individuals (Figure 1). Tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline cause significant hyposalivation (xerostomia) and potentiate the vasoconstrictive action of epinephrine, a common component of dental local anesthetic formulations. The macrolide group of antibiotics such as erythromycin and clarithromycin and the azole antifungals like fluconazole can inhibit the metabolism of lipid lowering statins (HMG-CoA [5- hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A] reductase inhibitors) such as simvastatin thereby potentiating their effects. Macrolides and azole antifungals also potentiate the adverse effects of statins such as increased risk for myopathy/rhabdomyolysis due to decreased metabolism. Also, many patients turn to alternative therapies such as herbal medications to manage an array of medical conditions 13. Gingko biloba, ginseng, garlic and ginger are readily available herbal medicines that can inhibit platelet activity and thereby promote excessive bleeding after dental surgery 14,15. To keep abreast of drug information updates, several print and online drug reference manuals are readily available including the ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ (https://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/online-for-dentistry/)16, a concise drug database for dentists with entries on drug adverse effects that may potentially alter dental treatment outcomes. ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ is marketed as a web-based drug reference database providing ease of access to dental-specific drug information, medication alerts and drug interactions to ensure medication and treatment safety in the dental setting 16. While the information on dental treatment complications often prompts the clinician to seek additional published information on the drug actions, it is unclear if the specific entries on dental and medical management complications are based on evidence from original research that detail these associations. The aim of this study was to review and identify database drug categories associated with evidence-based drug-related medical complications during dental treatment. We reviewed and identified the drug entries in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’16 that are associated with highest propensity to alter patient-specific dental treatment plan and assessed whether the associated adverse drug actions correlate with evidence from published literature.

Figure 1.

Drug induced gingival overgrowth (black star) in a young patient.

Methods

PubMed®, EMBASE®, and Scopus® databases were searched for drug related articles published from July 1975 through July 2019 that were associated with drug-related medical complications using the following search terms or phrases commonly used in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’16: adverse drug reaction, dental treatment, xerostomia, local anesthetic, anesthetic precaution, dental complication, bleeding, altered medical management. Two independent reviewers screened the search results based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 17 to identify full text articles with recommendations on drug-related medical complications during dental treatments or drug-related alterations in dental treatment (Figure 2). The articles were further assigned to one of the following publication categories: case reports, controlled trials, reviews, conference reports or letters. Additionally, each drug record in Lexicomp Online for Dentistry16 was searched for report or warnings that may potentially alter dental clinical decision making such as local anesthetic cautions, xerostomia and bleeding complications which were the most common recommendations in the ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ database. All identified drugs were assigned to different groups based on therapeutic categories. A drug category was assigned if five or more drugs were associated with some form of medical complication. Categories with less than five drugs were merged into a miscellaneous (others) category.

Figure 2.

Search strategy based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 17

A summary table was generated to correlate drug categories with local anesthetic precaution, xerostomia, bleeding and a combination of xerostomia with bleeding. A Pearson’s Chi-squared test of the summary table was performed using the null hypothesis that all the drug categories have similar probability for potential medical complications. Statistical significance suggesting that at least one drug category demonstrated a high propensity for medical complications was set at p < 0.05. Furthermore, pairwise comparison was performed for the drug categories and significance level was calculated using Bonferroni correction of 0.05 divided by number of total tests.

Results

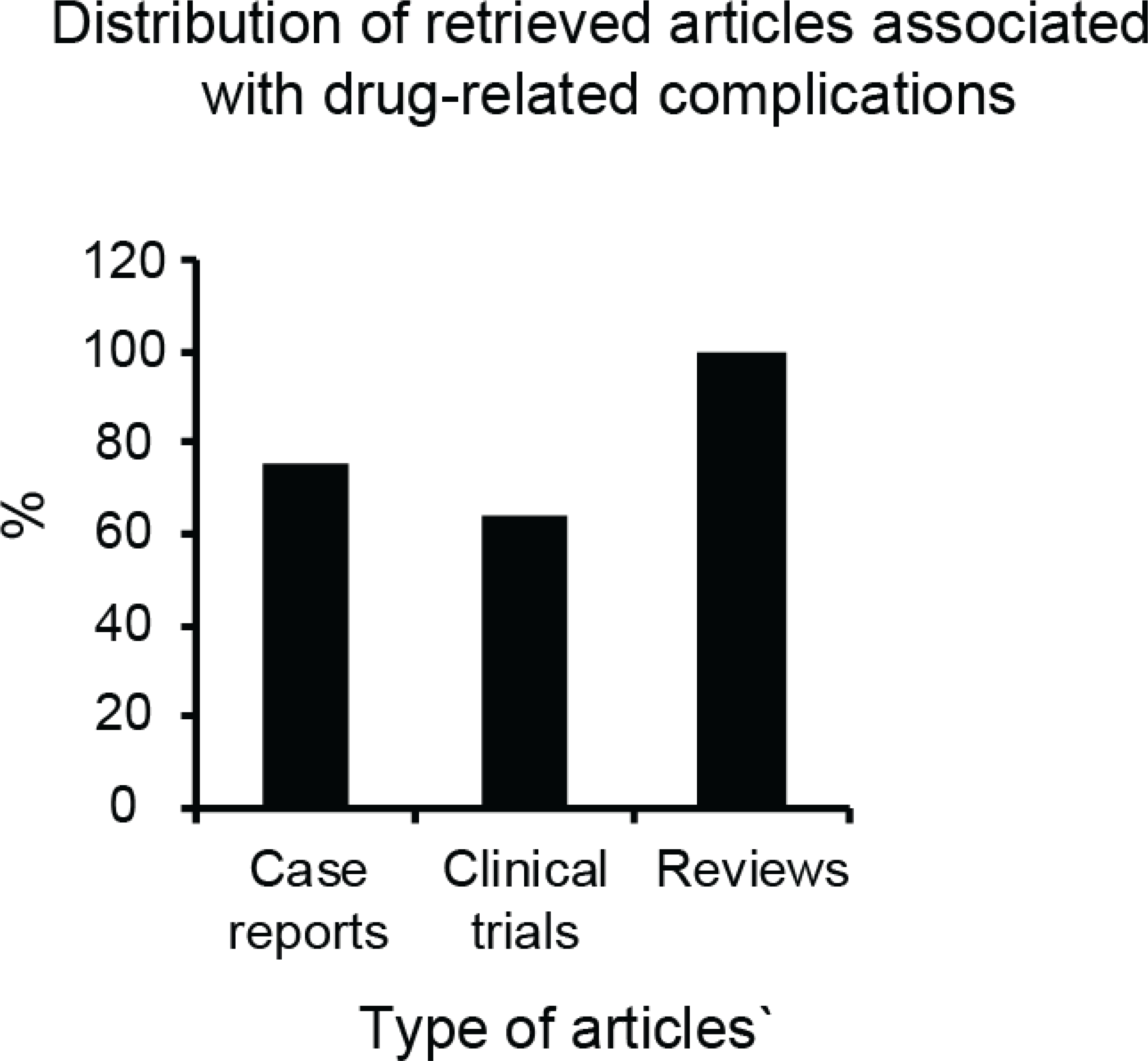

A total of 5251 non-duplicate publications were identified based on search criteria using several search strategies (PubMed® =1632; Embase® =1804; and Scopus® =1815). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria and review of titles and abstracts, 670 full-text were retrieved for review. Publications addressing drug-related complications included 37 of 49 (75.51%) clinical cases, 216 of 338 (63.91%) clinical trials and 283 of 283 (100%) review articles (Figure 2). After screening the full-text articles, 471 articles published with dental adverse effect as the primary outcome were selected for review (Figure 3). There were 1973 drugs in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ with cautions regarding drug-related medical complications during dental treatment. These were sorted into 59 drug categories according to database information and those with highest risks of medical complications were summarized as shown in Tables 1 to 5. Only 54 publications (1.2% of all full text articles) reported original studies that directly tested drug associations with dental management complications.

Figure 3.

Distribution of retrieved articles associated with drug-related complications

Table 1.

Drugs associated with local anesthetic precautions summarized into different categories. [Drug categories with less than five drugs associated with dental management complications were merged together as ‘Others’]

| Drugs associated with local anesthetic precautions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Category | Total | Drugs associated with complications | |

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Antipsychotic/Antidepressants | 84 | 68 | 80.95 |

| Antihistamine | 68 | 39 | 57.35 |

| Anticholinergic | 41 | 22 | 53.66 |

| Respiratory | 41 | 17 | 41.46 |

| Analgesic | 90 | 37 | 41.11 |

| Neurologic | 106 | 43 | 40.57 |

| Cancer Therapy | 61 | 20 | 32.97 |

| Cardiovascular | 145 | 26 | 17.93 |

| Gastrointestinal | 49 | 7 | 14.29 |

| Supplement | 66 | 6 | 9.09 |

| Antimicrobial | 295 | 23 | 7.80 |

| Others | 549 | 47 | 8.56 |

| Total | 1595 | 355 | 22.66 |

Table 5.

Summary of clinical trials and case reports that directly addressed drug-related dental complications.

| Clinical trials and reports specifically addressing drug-related dental complications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Drug Categories |

||||

| Antipsychotic/Antidepressants | Anticoagulants | Cancer Therapy | Analgesics | ||

| Clinical Trials | 46 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 40 |

| Case Reports | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Antipsychotics/antidepressants ranked as the top drug category associated with three of four most common dental management complications that include local anesthetic complication (80.95%, Table 1) xerostomia (81.93, Table 2) and a combination of xerostomia and bleeding (22.89%, Table 4). Antipsychotics/antidepressants, antihistamines and anticholinergics were also the top three contributors with respect to xerostomia (Table 2) and local anesthetic precautions (Table 1) while anticoagulants (80%) and cancer chemotherapeutic agents (59.21%) ranked first and second respectively in the bleeding complication category (Table 3). Pearson’s Chi-squared test showed that several drug categories in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ are associated with drug-related dental treatment cautions on local anesthetic precaution (p<0.001), xerostomia (p<0.001), bleeding (p<0.001) and both xerostomia/bleeding (p<0.001). Further pairwise comparison of the drug categories also demonstrated that the database has a similarly high propensity to recommend cautions when a patient is taking multiple medications [local anesthetic precaution (p < 0.001), xerostomia (p<0.001), bleeding (p<0.001) and both xerostomia/bleeding (p<0.005)].

Table 2.

Drugs associated with xerostomia precautions summarized into different categories. [Drug categories with less than five drugs associated with dental management complications were merged together as ‘Others’]

| Drugs associated with xerostomia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Category | Total | Drugs associated with complications | |

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Antipsychotic/Antidepressants | 83 | 68 | 81.93 |

| Antihistamine | 68 | 39 | 57.35 |

| Anticholinergic | 41 | 22 | 53.66 |

| Respiratory | 40 | 17 | 42.50 |

| Analgesic | 90 | 37 | 41.11 |

| Neurologic | 105 | 42 | 40.00 |

| Cardiovascular | 145 | 26 | 17.93 |

| Cancer Therapy | 152 | 22 | 14.47 |

| Gastrointestinal | 47 | 5 | 10.64 |

| Antimicrobial | 304 | 29 | 9.54 |

| Supplement | 68 | 5 | 7.35 |

| Others | 589 | 46 | 7.81 |

| Total | 1732 | 358 | 20.67 |

Table 4.

Drugs associated with a combination of xerostomia and bleeding precautions summarized into different categories. [Drug categories with less than five drugs associated with dental management complications were merged together as ‘Others’]

| Drugs associated with xerostomia and bleeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Category | Total | Drugs associated with complications | |

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Antipsychotic/Antidepressants | 83 | 19 | 22.89 |

| Analgesic | 90 | 12 | 13.33 |

| Cancer Therapy | 152 | 12 | 7.89 |

| Antimicrobial | 304 | 8 | 2.63 |

| Others | 589 | 46 | 7.81 |

| Total | 946 | 61 | 6.45 |

Table 3.

Drugs associated with bleeding precautions summarized into different categories. [Drug categories with less than five drugs associated with dental management complications were merged together as ‘Others’]

| Drugs associated with bleeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Category | Total | Drugs associated with complications | |

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Anticoagulant | 30 | 24 | 80.00 |

| Cancer Therapy | 152 | 90 | 59.21 |

| Analgesics | 90 | 41 | 45.56 |

| Homeostatic Agents | 23 | 9 | 39.13 |

| Antirheumatic | 13 | 5 | 38.46 |

| Antilipemic | 18 | 5 | 27.78 |

| Immunotherapy | 29 | 8 | 27.59 |

| Antipsychotic/Antidepressants | 83 | 20 | 24.10 |

| Neurologic | 105 | 12 | 11.43 |

| Antimicrobial | 304 | 26 | 8.55 |

| Endocrine | 79 | 6 | 7.59 |

| Others | 619 | 27 | 4.36 |

| Total | 1545 | 273 | 17.67 |

Discussion

This study addresses the expanding professional interest in identifying the relationships among systemic diseases, chronic therapeutic treatments, as well as comorbidities and drug actions that complicate dental care. Based on ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ database entries of drugs associated with procedural warnings that may prompt changes in dental-decision making, antipsychotics/antidepressants clearly ranked highest in three of four caution categories while antihistamines ranked 2nd in two of four caution categories. The high association of antipsychotics/antidepressants with medical cautions during dental treatment may be related to the fact that antipsychotics/antidepressants are commonly prescribed in the United States and Europe 18. These drugs are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States for multiple indications besides schizophrenia (bipolar mania, adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder, irritability associated with autism) and they are commonly used ‘off label’ in many other conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and orofacial pain disorders 19. Since psychiatric disorders are common across multiple age groups whether in urban or rural populations 20, this observation underscores the fact that a high number of dental patients may be on medications that pose a risk of adverse drug reaction requiring alterations to dental treatment plan. Particularly, many patients with psychiatric disorders are usually on multiple antipsychotic drugs 21. Antipsychotics/antidepressants inhibit several cytochrome P450 isoenzymes that are essential for the metabolism of other drugs, such as CYP2D6 that is essential for the metabolism of opioids. 7 Therefore, medication list of patients should be carefully scrutinized to identify potential drug-related medical complications. Notably, most antipsychotic drugs inhibit dopamine receptors, histamine, cholinergic and alpha adrenergic receptors, so they accentuate complications such as xerostomia, sialorrhea, dysgeusia, stomatitis, glossitis and bruxism when combined with other drugs 7. In addition to effects of medication-induced xerostomia, patients diagnosed with depression may be less motivated to maintain optimal oral hygiene 2,22 making them even more susceptible to higher incidence of dental caries and periodontal disease 23.

Unlike, several herbal medications that inhibit platelet activity 14, the direct action of antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) on postsurgical bleeding is still unclear 24,25. While postsurgical bleeding has been associated with SSRI-induced depletion of serotonin from platelets, other studies found no such association 24,26. However, direct relationship to dental bleeding or other management complications was not assessed in majority of these studies other than subjective reports of oral dryness (Figure 4). Severe oral dryness further predisposes to mucosal bleeding, that further complicates the adverse effects of the drug complications 27. While antipsychotic/antidepressants were most commonly associated with dental treatment modifications according to the Lexicomp drug database, there are other adverse drug actions that can significantly impact dental treatment. The risk of excessive bleeding during dental surgery is especially high in patients with cardiac arrhythmias, prosthetic heart valves, coronary artery stents, myocardial infarction and deep vein thrombosis because they are often on anticoagulant therapy 28–30. In this category of patients, the healthcare provider must make adequate plan to control excessive bleeding or modify the treatment plan accordingly. Additionally, a significant number of dental patients may also be on long term use of antiepileptic, antiretroviral, antihypertensive or chemotherapeutic agents that have been associated with kidney and/or liver damage. Hence, it is important to monitor renal and hepatic functions before placing these groups of dental patients on antimicrobials for acute infections to ensure proper metabolism and elimination of the drugs from the body. Analgesics and anesthetic agents should also be used cautiously until adequate medical care is established and hepatic and renal functions improve 31,32. Long-term use of NSAIDs can reduce the effectiveness of beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors and diuretics. Also, selective COX-2 inhibitors such as Celebrex, have also been associated with severe cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents that can also occur during routine dental treatment 33. The clinician will need to minimize the stress of dental treatment and keep duration of dental appointments short. Furthermore, dental patients on insulin therapy may be susceptible to diabetic shock from hypoglycemia if kept on the dental chair for prolong dental procedures. This severe medical emergency can be readily avoided with adequate planning.

Figure 4.

Drug induced oral dryness. This patient developed chemotherapy induced generalized oral dryness. The dorsum of the tongue displayed depapilation of the filiform papillae, hyperpigmentation, fibrosis (arrow head) and candidal overgrowth (clear arrow).

Drug-drug interactions are an obvious major concern for dental healthcare professionals because we identified 1595 drug entries in the Lexicomp online drug database for dentistry that were associated with local anesthetic precautions. This is highly significant considering that local anesthetics are the most commonly used drugs in dentistry. Although not a top category listed in this study, benzodiazepines commonly used to treat anxiety and insomnia may cause a patient to develop tolerance to anesthesia prompting the clinician to give higher doses of local anesthetics for dental procedures 34. Also, tricyclic antidepressants tend to potentiate the vasoconstrictive action of epinephrine, a common component of local anesthetics cartridges used in dentistry. It is vital to also consider that oral ulceration, lichenoid eruptions (Figure 5), hyperpigmentation, mucosal swelling and taste alterations are common oral adverse drug reactions, but these rarely cause significant alterations in dental treatment 2. Of the 46 clinical trials identified (Table 5), 40 studies focused mainly on analgesics, so there is still paucity of data from hypothesis driven studies that assessed direct relationships between different drugs and dental treatment complications. Therefore, more original studies to address the knowledge gap in this area are still warranted. There are some weaknesses of the current study. The methodology used in this systematic review focused mainly on dental treatment complications that are recurrently listed in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ drug database which obviously introduced an inherent bias to search terms selected. However, databases that document specific cardiovascular (e.g. hypertension), metabolic (e.g. diabetes mellitus), hematological (e.g. anemia, bleeding) and central nervous system (e.g. cognition) related issues will be more clinically-relevant to dental practitioner treating medically complex patients related issues

Figure 5.

Oral lichenoid drug reaction. This patient developed lichenoid drug reaction of oral mucosa (black arrows) to a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Conclusions and Relevance to practicing dentist:

In summary, only a limited number of drug-related cautions in ‘Lexicomp Online for Dentistry’ are associated with published evidence. A wide gap exists in the evidence-based recommendations on drug-related medical complications that impact dental treatment. The limited number of evidence-based clinical studies is expected because ethical issues make it conceptually impracticable to conduct well powered randomized controlled trials. With additional well-designed studies, it will be easier to categorially simplify drug-related medical complications and warnings into low, medium and high-evidence warnings. This will more appropriately guide dental practice as clinicians will be better informed to make evidence-based decisions.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by United Stated Department of Health and Human Services/National Institutes of Health grants CA169089 and DE022932 (to SOA). We thank Lu Chen and Dr. Jinbo Chen, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Biostatistics and Epidemiology Department for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to authorship and/or publication of article.

References

- 1.Tavares M, Lindefjeld Calabi KA, San Martin L. Systemic diseases and oral health. Dent Clin North Am 2014;58:797–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zavras AI, Rosenberg GE, Danielson JD, Cartsos VM. Adverse drug and device reactions in the oral cavity: surveillance and reporting. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144:1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner L, Mupparapu M, Akintoye SO. Review of the complications associated with treatment of oropharyngeal cancer: a guide for the dental practitioner. Quintessence Int 2013;44:267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ojha J, Bhattacharyya I, Islam N, Cohen DM, Stewart CM, Katz J. Xerostomia and lichenoid reaction in a hepatitis C patient treated with interferon-alpha: a case report. Quintessence Int 2008;39:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg MS, Glick M, Ship JA. Introduction to Oral Medicine and Oral Diagnosis: Evaluation of the Dental Patient. In: Greenberg MS, Glick M, Ship JA, (eds). Burket’s Oral Medicine. 11th ed: BC Decker, 2008:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hersh EV, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions in dentistry. Periodontol 2000 2008;46:109–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker DE. Adverse drug interactions. Anesth Prog 2011;58:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akintoye S Osteonecrosis of the jaw from bone anti-resorptives: impact of skeletal site-dependent mesenchymal stem cells. Oral Dis 2014;20:221–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mupparapu M Editorial: Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ): Bisphosphonates, antiresorptives, and antiangiogenic agents. What next? Quintessence Int 2016;47:7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAOM. AAOM clinical practice statement: Subject: The use of serum C-terminal telopeptide cross-link of type 1 collagen (CTX) testing in predicting risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2017;124:367–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz HC. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw−-2014 update and CTX. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;73:377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther 2007;29 Suppl:2477–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abebe W, Herman W, Konzelman J. Herbal supplement use among adult dental patients in a USA dental school clinic: prevalence, patient demographics, and clinical implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011;111:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong WW, Gabriel A, Maxwell GP, Gupta SC. Bleeding risks of herbal, homeopathic, and dietary supplements: a hidden nightmare for plastic surgeons? Aesthet Surg J 2012;32:332–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abebe W Review of herbal medications with the potential to cause bleeding: dental implications, and risk prediction and prevention avenues. EPMA J 2019;10:51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lexicomp. Lexicomp online database for dentistry. Philadelphia PA: WOLTERS KLUWER HEALTH, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audi S, Burrage DR, Lonsdale DO, et al. The ‘top 100’ drugs and classes in England: an updated ‘starter formulary’ for trainee prescribers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:2562–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez XF, Sundararajan T, Covington EC. A Systematic Review of Atypical Antipsychotics in Chronic Pain Management: Olanzapine Demonstrates Potential in Central Sensitization, Fibromyalgia, and Headache/Migraine. Clin J Pain 2018;34:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslau J, Marshall GN, Pincus HA, Brown RA. Are mental disorders more common in urban than rural areas of the United States? J Psychiatr Res 2014;56:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toteja N, Gallego JA, Saito E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy in children and adolescents receiving antipsychotic treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014;17:1095–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No SMA 18–5068, NSDUH Series H-53. Rockville MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 5600 Fishers Lane, Room 15-E09D, Rockville, MD; 20857, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedlander AH, Marder SR, Pisegna JR, Yagiela JA. Alcohol abuse and dependence: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:731–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvajal A, Ortega S, Del Olmo L, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and gastrointestinal bleeding: a case-control study. PLoS One 2011;6:e19819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang SM, Han C, Bahk WM, et al. Addressing the Side Effects of Contemporary Antidepressant Drugs: A Comprehensive Review. Chonnam Med J 2018;54:101–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salkeld E, Ferris LE, Juurlink DN. The risk of postpartum hemorrhage with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plemons JM, Al-Hashimi I, Marek CL, American Dental Association Council on Scientific A. Managing xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction: executive summary of a report from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145:867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Diermen DE, van der Waal I, Hoogstraten J. Management recommendations for invasive dental treatment in patients using oral antithrombotic medication, including novel oral anticoagulants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013;116:709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firriolo FJ, Hupp WS. Beyond warfarin: the new generation of oral anticoagulants and their implications for the management of dental patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012;113:431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deppe H, Mucke T, Auer-Bahrs J, Wagenpfeil S, Kesting M, Sculean A. Bleeding complications following Nd:YAG laser-assisted oral surgery vs conventional treatment in cardiac risk patients: a clinical retrospective comparative study. Quintessence Int 2013;44:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radmand R, Schilsky M, Jakab S, Khalaf M, Falace DA. Pre-liver transplant protocols in dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013;115:426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brockmann W, Badr M. Chronic kidney disease: pharmacological considerations for the dentist. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:1330–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kufta K, Saraghi M, Giannakopoulos H. Cardiovascular considerations for the dental practitioner. 1. Review of cardiac anatomy and preoperative evaluation. Gen Dent 2017;65:50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dionne RA, Yagiela JA, Cote CJ, et al. Balancing efficacy and safety in the use of oral sedation in dental outpatients. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:502–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]