Highlights

-

•

A dominance analysis of psychological variables associated to BD is proposed.

-

•

Positional, inter-individual and intra-individual factors were investigated.

-

•

The variables most associated to BD were enhancement motives and drinking identity.

-

•

The second order variables associated with BD were subjective norm and social motives.

-

•

Prevention actions may benefit of specifically targeting inter-individual variables.

Keywords: Binge drinking, University students, Identity, Enhancement motives, Subjective norm, Social motives

Abstract

Introduction

Binge drinking (BD) is a public health concern, especially in young people. Multiple individual factors referring to different level of analyses - positional, inter-individual and intra-individual – are associated to BD. As they have mainly been explored separately, little is known about the psychological variables most associated with BD. This study, based on an integrative model considering a large number of variables, aims to estimate these associations and possible dominance of some variables in BD.

Methods

A sample of university students (N = 2851) participated in an internet survey-based study. They provided information on alcohol related variables (AUDIT, BD score), positional factors (sex, age), inter-individual factors (subjective norm, social identity, external motivations), and intra-individual factors (internal motivations, meta-cognitions, impulsivity and personality traits). The data were processed via a backward regression analysis including all variables and completed with a dominance analysis on variables that are significantly associated with BD intensity.

Results

The strongest variables associated with BD intensity were enhancement motives and drinking identity (average ΔR2 = 21.81%), followed by alcohol subjective norm and social motives (average ΔR2 = 13.99%). Other associated variables (average ΔR2 = 2,84%) were negative metacognition on uncontrollability, sex, coping motives, lack of premeditation, positive metacognition on cognitive self-regulation, positive urgency, lack of perseverance, age, conformity motives and loneliness.

Conclusion

Results offer new avenues at the empirical level, by spotting particularly inter-individual psychological variables that should be more thoroughly explored, but also at the clinical level, to elaborate new prevention strategies focusing on these specific factors.

1. Introduction

Binge drinking (BD), an alcohol consumption pattern frequently used by students for recreational purposes, has increased significantly over the last decades in most Western countries. BD is usually defined as a heavy alcohol consumption over a short period (4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men in a two-hour interval in the USA according to NIAAA) and is associated with major personal, cognitive, academic and social negative consequences (e.g., Townshend, Kambouropoulos, Griffin, Hunt, & Milani, 2014). Since it is considered as a major public health issue, the community is looking for new effective prevention methods (see Cronce et al., 2018). These strategies can be either environmentally-focused (e.g., implementing minimum drinking age laws, Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002) or individually-focused (e.g., personalized normative feed-back, Vallentin-Holbech, Rasmussen, & Stock, 2018). Among the latter, most strategies are targeting one or several psychological variables associated to BD (e.g., subjective norm modification is the aim of personalized normative feed-back) to prevent this behavior. Yet, two elements hinder the arbitration and selection of the most important BD psychological factors to target in prevention campaigns. Namely, several psychological factors have been documented as being associated to BD and they have mainly been considered separately. We therefore propose a new classification to approach multiple BD correlates in order to arrange their complementary and/or specific role. Indeed, researches on psychological variables can be ranged according to their level of analysis contrasting positional (i.e., based on individuals’ place in the environment such as status, roles, or positions), inter-individual (i.e., mechanisms based on the relation between individuals) and intra-individual levels (i.e., internal mechanisms, Doise, 1982). As this provides a framework for the organization of an analysis including many different variables, this approach can constitute a new stimulating perspective to understand a multidetermined phenomenon such as BD.

At the positional level, studies on BD reported a higher prevalence among men than women and among young adults than older ones (e.g., Luo, Agley, Hendryx, Gassman, & Lohrmann, 2015).

At the inter-individual level, social factors have been considered in reference to socio-normative (subjective norm and drinking identity) and motivational variables. First, research has mainly evidenced that the higher the perceived approval and/or adoption of alcohol use by significant people such as peers, the higher the compliance to BD (for a meta-analysis, see Borsari & Carey, 2003). If the subjective norm is classically considered in global models explaining behaviors (mostly inspired by the Theory of Planned Behavior, Ajzen, 2002), recent studies evidenced that social identity (i.e., the extent to which individuals view themselves as a member of a social category, can constitute another key variable; e.g., Rise, Sheeran, & Hukkelberg, 2010). And indeed, specific to alcohol issues, drinking identity (i.e., the extent to which individuals view themselves as drinkers; e.g., Lindgren, Ramirez, Olin, & Neighbors, 2016), constitutes another positive correlate of frequency consumption, alcohol quantity or BD (e.g., Hagger, Anderson, Kyriakaki, & Darkings, 2007). Second, Cooper’s motivational model (Cooper, 1994) identified two external drinking motives: social (i.e., positive external motives such as drinking to boost social interactions during a party), and conformity (i.e., negative external motive such as drinking to avoid social censure or rejection) motivations. A higher level of social motives is associated with a higher drinking frequency and quantity, whereas a higher level of conformity motives is related to lower drinking levels (Cooper, 1994).

At the intra-individual level, psychological factors have been considered in reference to self-regulation and personality or emotional variables. For self-regulation variables, on the one hand Cooper (1994, op. cit.) identified internal motivations through enhancement (i.e., positive internal motive such as drinking to increase positive mood) and coping (i.e., negative internal motive such as drinking to regulate negative affect) motives to binge. Higher levels of enhancement and coping motives are associated with higher drinking frequency and quantity (Lannoy, Billieux, Poncin, & Maurage, 2017). On the other hand, metacognitive processes have also been associated with BD (e.g., Clark et al., 2012). Metacognitions are defined as schematic information that individuals hold about the significance of their cognitive experiences and ways to control it, and were considered in alcohol research, especially regarding their valence (Spada & Wells, 2008). Positive metacognitions are a specific form of expectancy related to alcohol use as a way to regulate emotional and cognitive functioning. Conversely, negative alcohol-related metacognitions refer to the lack of control over alcohol use and its potential cognitive harm.

Concerning personality and emotional variables, impulsivity (i.e., the tendency to act prematurely without fully considering the action’s consequences) is classically associated with BD (Caswell, Bond, Duka, & Morgan, 2015). More precisely, recent research has mostly identified an association between BD and the dimensions of negative urgency (i.e., the tendency to act rashly to regulate negative emotions; Bø, Billieux, & Landrø, 2016), lack of premeditation (i.e., the tendency to favor immediate reward options without regarding potential consequences of the action; VanderVeen, Cohen, & Watson, 2013), and sensation seeking (i.e., the tendency to seek out new or thrilling experience; Shin, Hong, & Jeon, 2012). In addition, some data have shown a positive association with anxiety (e.g., Strine et al., 2008) or depression symptoms (e.g., Schuler, Vasilenko, & Lanza, 2015) and a possible negative association with loneliness (i.e., a distressing feeling of isolation perception or social rejection, Varga & Piko, 2015).

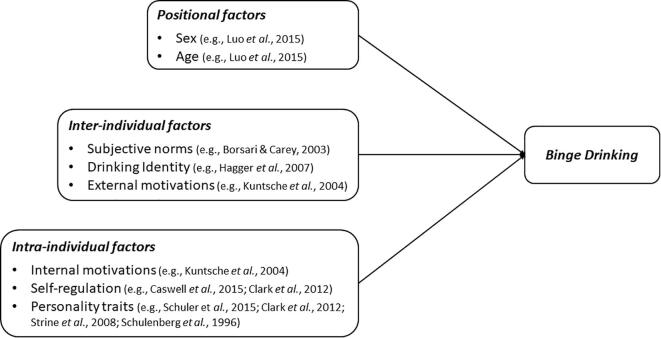

In sum, previous studies evidenced the role of several psychological factors in BD that can be classified into three main approaches (Fig. 1). However, little is known about these factors’ relative contribution for explaining BD as they were mostly considered in isolation. As these factors can be likely inter-correlated, studying these variables separately may have led to overestimate their respective implication and it seems therefore crucial to address their relative contribution to BD. By simultaneously assessing a large number of psychological factors known to be related to BD, this study aimed (i) to confirm or not their significant role in BD, (ii) to examine the strength of their relative contribution and (iii) to identify the most contributive factors to BD. Further, to counteract the limitations of traditional statistical methods assessing the strength of factors in models, we assessed the relative importance of psychological factors in BD by performing a dominance analysis.

Fig. 1.

Individual factors of Binge Drinking ranged into the three levels of analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Procedure and participants

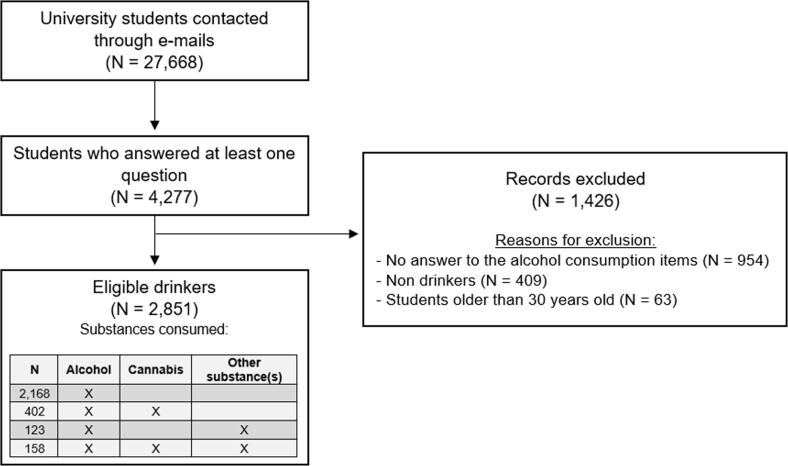

We recruited a convenience sample of 2851 students (see Fig. 2 for the flow diagram and Table 1 for the participants characteristics1) from the University of Caen Normandy (France) through an online survey (November 2017). This study was included in a larger research project exploring substance consumption among young adults2 (ADUC project: “Alcool et Drogues à l’Université de Caen”). Response rate (15,7%3) and ratio between completed response and included participants (67.17%) were similar to previous studies carried out among college students (e.g., Ehret et al., 2013, Lannoy et al., 2020, Neighbors et al., 2006). The survey was created with the Limesurvey® application and hosted by the server of the University. No compensation was provided to the participants.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics on interest variables.

| Socio demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Females, N (%) | 1793 (62.9%) | |

| Males, N (%) | 1058 (37.1%) | |

| Age (in years) | 20.50 (2.00) | |

| Alcohol use | ||

| AUDIT total score | 7.32 (5.45) | |

| Binge drinking score | 22.70 (20.90) | |

| Q1/ BD Sub-score 1 | 1.80 (1.16) | |

| Q2/ BD Sub-score 2 | 8.33(14.5) | |

| Q3/ BD Sub-score 3 | 33.5 (31.1) | |

| Personnality and Emotional variables | ||

| STAI-T | 47.80 (11.80) | |

| BDI | 7.71 (6.13) | |

| ESUL | 35.30 (11.50) | |

| UPPS-N – Negative urgency | 9.07 (2.83) | |

| UPPS-P – Positive urgency | 10.70 (2.52) | |

| Premeditation (lack of) | 7.59 (2.28) | |

| Perseverance (lack of) | 7.55 (2.48) | |

| Sensation seeking | 10.20 (2.87) | |

| Metacognitions | ||

| PAMS – Emotional S.R. | 20.80 (5.79) | |

| PAMS – Cognitive S.R. | 5.36 (1.72) | |

| NAMS – Uncontrollability | 3.29 (0.91) | |

| NAMS – Cognitive harm | 6.04 (2.64) | |

| Motivations | ||

| DMQ-R - Social | 8.86 (3.34) | |

| DMQ-R - Coping | 5.76 (2.97) | |

| DMQ-R - Enhancement | 8.48 (3.34) | |

| DMQ-R - Conformity | 4.47 (2.25) | |

| Socio-normative variables | ||

| Subjective norm - Alcohol | 2.21 (1.44) | |

| Drinking identity - Alcohol | 1.52 (1.05) | |

Note. Except for sex, data show means (standard deviations) ; ESUL : Echelle de Solitude de l’Université de Laval (loneliness measure) ; STAI-T : State-Trait Anxiety Inventory ; UPPS : Impulsive Behavior Scale ; BDI : Beck Depression Inventory ; AUDIT : Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test ; PAMS & NAMS : Positive and Negative Alcohol Metacognitions Scales (S.R. : Self-Regulation); DMQR: Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised.

2.2. Ethics

The study was notified and authorized by the “Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés” with the registration number u24-20171109-01R1. Besides students being solicited through their formal university e-mail addresses, the University Information System Direction (DSI) developed a security system between servers guaranteeing complete anonymity to responders. The e-mail contained information on the study aims and an informed consent form specifying that participation was not mandatory.

2.3. Measures

Details of all measures described below are available at OSF (Open Science Framework:https://osf.io/6e84m/?view_only https://osf.io/6e84m/?view_only=b96617b7facf4a2ea2428f8ca998795f). The items were presented to participants in the following order:

2.3.1. Socio-demographics variables, namely age, gender and native language4.

1.3.2. Alcohol related variables. Alcohol consumption was assessed using the French version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Cronbach α = 0.79; Gache et al., 2005). AUDIT is a 10-item measure designed to identify individuals at risk for alcohol-related problems, or who are actually experiencing such problems. The AUDIT has been validated and recommended as an effective alcohol measure in college students (DeMartini & Carey, 2012). More central to our purpose, a BD score (Townshend & Duka, 2002) was calculated using three questions (i.e., Q1: “number of average standard drinks (corresponding to 10 gr of ethanol in France) per hour”, Q2: “number of times being drunk in the previous 6 months” and Q3: “percentage of times getting drunk when drinking”). The score computation was (4 × Q1) + Q2 + (0.2 × Q3)5. This score, unlike the more classical measurement “drinks in a row” focusing only on the quantity of alcohol consumed, considers both quantity and frequency of consumption. It hence integrates repeated withdrawal from alcohol and is of high interest to focus on the specific pattern of drinking that is BD (Townshend & Duka, 2005; for a review on different possible measures of BD, see Maurage et al., 2020).

Alcohol metacognitions were assessed through the French version of the Positive Alcohol Metacognitions Scale (PAMS) and the Negative Alcohol Metacognitions Scale (NAMS; Likert-type scales from 1 = do not agree to 4 = agree very much; Gierski et al., 2015). The PAMS (12 items) assesses positive metacognitions about alcohol use, including metacognitions about emotional (Cronbach α = 0.91) and cognitive (Cronbach α = 0.79) self-regulation. The NAMS (6 items) assesses negative metacognitions by measuring uncontrollability (Cronbach α = 0.78) and cognitive harm (Cronbach α = 0.83).

Socio-normative variables were measured through the perceived subjective norm and social identity linked to alcohol use. Subjective norm (3-item Likert-type scale scored from 1 = do not agree to 7 = agree very much and 1 item from 1 = no person to 6 = 5 persons, the latter being adjusted after data gathering; Cronbach α = 0.83; items derived from the Theory of Planned Behavior; Ajzen, 2002) assesses how much most of the participants’ significant relatives approve and/or adopt alcohol consumption to “get smashed”. Drinking identity (2-item Likert-type scale from 1 = do not agree to 4 = agree very much; Cronbach α = 0.77; items adapted from Callero, 1985) assesses the extent to which excessive alcohol consumption is important to define the participant’s identity.

Drinking motives were assessed using the four-factor Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised (DMQ-R) in short form (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009) including social (Cronbach α = 0.85), coping (Cronbach α = 0.86), enhancement (Cronbach α = 0.81) and conformity (Cronbach α = 0.83) subscales (12-item Likert-type scales from 1 = never to 5 = always).

1.3.3. Impulsivity and Emotional measures. Impulsivity was measured using the French short version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (20-item Likert-type scale scored from 1 = do not agree to 4 = agree very much; Billieux et al., 2012) to measure five facets of impulsivity: positive urgency (Cronbach α = 0.74), negative urgency (Cronbach α = 0.79), lack of premeditation (Cronbach α = 0.79), lack of perseverance (Cronbach α = 0.87), and sensation seeking (Cronbach α = 0.82). Anxiety was measured using the French version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; 20-item Likert-type scale scored from 1 = no to 4 = yes; Cronbach α = 0.89; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) and depressive symptoms were assessed using the French version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-13; 13-item scale; Cronbach α = 0.88; Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988). Loneliness was measured through the ESUL (i.e., “Echelle de Solitude de l’Université de Laval”), a Canadian-French speaking adaptation of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (20-item Likert-type scale scored from 1 = never to 4 = often; Cronbach α = 0.90; De Grace, Joshi, & Pelletier, 1993).

2.4. Data analysis

The analyses were conducted using the program R version 4.0.1. As a first step, a backward linear regression analysis with repeated K-fold cross-validation was conducted to identify the factors, all centered, that are significantly associated to the BD score (Bruce, Bruce, & Gedeck, 2020). A repeated (N = 1000) 10-fold cross-validation method, evaluating the model performance on different subsets of the training data (i.e., a process to split the data) by repeating it a number of times (James, Witten, Hastie, & Tibshirani, 2014), was employed to counteract the limits of the backward regression method and account for the non-normality of the data. The best model identified is defined as the model that maximizes the R2, minimizes the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and takes into account a minimum of variables. As a second step, a bootstrapping dominance analysis (Azen and Budescu, 2003, Grömping, 2006, Nimon and Oswald, 2013) was conducted to estimate the relative weight of each factor in the selected model. One variable might be more important than the other when it contributes more to the explanation of the dependent variable (DV) at a given level of analysis. There are as many levels as there are factors in the model, the average contribution of a factor is thus calculated by averaging its contribution in each level of the analysis. A factor contribution of DV variance is defined by its square of part correlation (r2; i.e., the metric “lmg”; Grömping, 2006). This metric decomposes R2 (i.e., determination coefficient) into non-negative contributions that automatically sum to the total R2. This contribution is named general dominance. Besides, the general dominance is particularly relevant in combination with the bootstrapping method (Grömping, 2007) which provides bootstrap confidence intervals both for the relative importance of the factors and for their differences. The latter test the significant differences between factors contribution of the DV. In sum, a dominance analysis was processed using the bootstrapping method (N = 1000 samples) allowing us to rank the factors according to their relative importance on BD.

3. Results

The backward linear regression analysis evidenced a best 14-variable model (see Table 2), R2 = 0.512, F(14,1893) = 142, p < .001 (RMSE = 14.659; MAE = 10.172).

Table 2.

Summary of Stepwise linear regression with Backward method and repeated K-Fold cross-validation on BD score.

| Variables | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (F: −0.5; M: 0.5) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Age | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||

| PAMS - emotional dim. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PAMS – Cognitive reg. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||

| NAMS - Uncontrol. | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||||

| NAMS – Prejudice | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Subjective norm | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Drinking identity | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| DMQR– Social motives | * | * | ||||||||||||||||||

| DMQR–Coping motives | * | |||||||||||||||||||

| DMQR–Enhancement motives | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| DMQR–Conformity motives | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||

| UPPS - neg. urgency | ||||||||||||||||||||

| UPPS – pos. urgency | * | * | * | |||||||||||||||||

| UPPS – Premeditation | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| UPPS – Perseverance | ||||||||||||||||||||

| UPPS sens. seeking | ||||||||||||||||||||

| STAI-T | ||||||||||||||||||||

| BDI | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ESUL | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||||

| R2 Adjusted | 0.5032 | 0.5032 | 0.5032 | 0.5034 | 0.5039 | 0.5039 | 0.5038 | 0.5014 | 0.4987 | 0.4951 | 0.4946 | 0.4912 | 0.4913 | 0.4861 | 0.4759 | 0.472 | 0.4684 | 0.4612 | 0.4382 | 0.3226 |

| RMSE | 14.668 | 14.669 | 14.668 | 14.664 | 14.657 | 14.657 | 14.659 | 14.694 | 14.734 | 14.787 | 14.794 | 14.844 | 14.841 | 14.914 | 15.063 | 15.118 | 15.169 | 15.272 | 15.592 | 17.113 |

| MAE | 10.172 | 10.173 | 10.173 | 10.17 | 10.165 | 10.166 | 10.172 | 10.188 | 10.207 | 10.233 | 10.221 | 10.269 | 10.297 | 10.353 | 10.426 | 10.45 | 10.453 | 10.533 | 10.72 | 11.735 |

Note. PAMS & NAMS: Positive and Negative Alcohol Metacognitions Scales; Uncontrol. : Uncontrollability; DMQR: Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised; UPPS: Impulsive Behavior Scale; STAI-T: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; ESUL: Echelle de Solitude de l’Université de Laval (loneliness measure).

* variable included in the best model

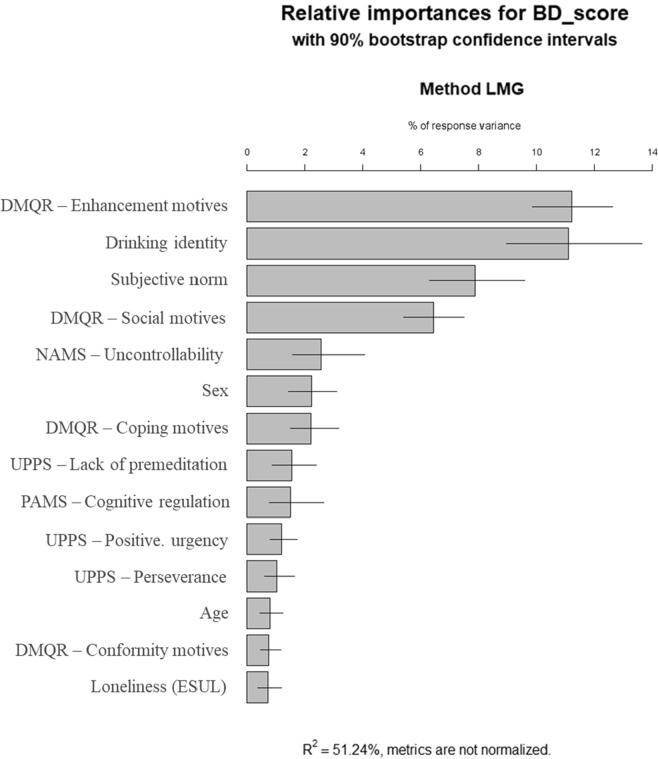

Then, the general dominance analysis indicated that the 14 significant variables were, from the highest relative weight to the lowest (see Table 3 and Fig. 3. for a graphic illustration), enhancement motives (ΔR2 = 20.93%, β = 0.257***, r2 = 0.1124), drinking identity (ΔR2 = 20.68%, β = 0.238***, r2 = 0.1111), subjective norm (ΔR2 = 15.38%, β = 0.175***, r2 = 0.0788), social motives (ΔR2 = 12.59%, β = 0.0740***, r2 = 0.0645), NAMS uncontrollability (ΔR2 = 5.02%, β = 0.0630***, r2 = 0.0257), sex (ΔR2 = 4.37%, β = 0.0950***, r2 = 0.0224), coping motives (ΔR2 = 4.29%, β = 0.0500*, r2 = 0.0220), UPPS lack of premeditation (ΔR2 = 3.02%, β = 0.0660***, r2 = 0.0155), PAMS cognitive regulation (ΔR2 2.93%, β = 0.0590**, r2 = 0.0150), UPPS positive urgency (ΔR2 = 2.34%, β = 0.0440*, r2 = 0.0120), UPPS perseverance (ΔR2 = 2.01%, β = 0.0370***, r2 = 0.0103), age (ΔR2 = 1.56%, β = -0.0670***, r2 = 0.0080), conformity motives (ΔR2 = 1.48%, β = -0.1060***, r2 = 0.0076), and loneliness (i.e., ESUL, ΔR2 = 1.40%, β = -0.0580***, r2 = 0.0072). All the remaining variables (UPPS negative urgency, UPPS sensation seeking, STAI, NAMS cognitive harm dimension, PAMS emotional dimensions, and BDI) were not significantly associated to the BD score variance.

Table 3.

Summary of the best 14-variable model on Binge Drinking Score (multiple linear regression) with bootstrapping dominance analysis (N = 1000).

| B | SE | 95% Confidence Interval |

β | Square of part correlation (r2) | 90% Confidence Interval for r2 |

% in R² | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | 5% | 95% | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 22.921 | 0.356 | 22.222 | 23.62 | |||||

| DMQR - Enhancement motives | 1.614 | 0.155 | 1.31 | 1.918 | 0.257*** | 0.112a | 0.099 | 0.127 | 21.93 |

| Drinking identity | 4.718 | 0.413 | 3.906 | 5.528 | 0.238*** | 0.111a | 0.089 | 0.135 | 21.68 |

| Subjective norm | 2.545 | 0.283 | 1.989 | 3.101 | 0.175*** | 0.079b | 0.064 | 0.096 | 15.38 |

| DMQR - Social motives | 0.468 | 0.154 | 0.165 | 0.77 | 0.074** | 0.065b | 0.055 | 0.075 | 12.59 |

| NAMS - uncontrollability | 1.545 | 0.447 | 0.668 | 2.422 | 0.063*** | 0.026c | 0.016 | 0.04 | 5.02 |

| Sex (F: −0.5; M: 0.5) | 4.209 | 0.749 | 2.738 | 5.678 | 0.095*** | 0.022c | 0.015 | 0.032 | 4.37 |

| DMQR - Coping motives | 0.348 | 0.138 | 0.076 | 0.619 | 0.050* | 0.022c | 0.015 | 0.031 | 4.29 |

| UPPS - Premeditation | 0.603 | 0.169 | 0.271 | 0.935 | 0.066*** | 0.016d | 0.009 | 0.024 | 3.02 |

| PAMS - Cognitive reg. | 0.724 | 0.224 | 0.283 | 1.164 | 0.059** | 0.015d | 0.007 | 0.027 | 2.93 |

| UPPS - Pos. Urgency | 0.375 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.044* | 0.012d | 0.008 | 0.018 | 2.34 |

| UPPS – Perseverance | 0.312 | 0.15 | 0.016 | 0.607 | 0.037* | 0.010d | 0.006 | 0.017 | 2.01 |

| Age | −0.664 | 0.165 | −0.987 | −0.34 | −0.067*** | 0.008d | 0.005 | 0.013 | 1.56 |

| DMQR - Conformity motives | −0.961 | 0.164 | −1.282 | −0.638 | −0.106*** | 0.008d | 0.005 | 0.012 | 1.48 |

| ESUL | −0.106 | 0.032 | −0.169 | −0.043 | −0.058*** | 0.007d | 0.004 | 0.012 | 1.40 |

Note : ESUL: Echelle de Solitude de l’Université de Laval (loneliness measure) ; UPPS: Impulsive Behavior Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; PAMS & NAMS: Positive and Negative Alcohol Metacognitions Scales; DMQR: Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised. Statistically significant at * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Fig. 3.

Relative weights of the 14 factors on BD score (with N = 1000 bootstrapping confidence intervals).

Lastly, based on the differences between factors’ weight on BD score, the 14 factors were classified into four ranks (see Table 3). The first rank included two variables (i.e., enhancement motives and drinking identity, average ΔR2 = 21.81%), two variables for the second rank (i.e., subjective norm and social motives, average ΔR2 = 13.99%), three variables for the third rank (i.e., NAMS uncontrollability, sex, and coping motives, average ΔR2 = 4.56%) and seven variables for the fourth rank (i.e., UPPS lack of premeditation, PAMS cognitive regulation, UPPS positive urgency, UUPS perseverance, age, conformity motives, and loneliness, average ΔR2 = 2.11%).

4. Discussion

This study uses an integrative model to identify the psychological factors that are significantly associated to BD; and among them, those which are most strongly associated with BD in university students. First, when confronting the results to an integrative approach, it turns out that 6 out of the 20 variables tested were not significantly associated with BD. Second, among the remaining significant factors associated to BD, the dominance analysis evidenced four decisive variables associated to BD: enhancement motives, drinking identity, subjective norm, and social motives. These results lead to several implications both at the empirical and prevention levels.

First, although positional (sociodemographic variables) and intra-individual (self-regulation processes and personality traits) factors have been largely documented, BD behavior actually appears to be also well explained at an inter-individual level. Indeed, the four strongest factors associated with BD are psychosocial variables dealing with the self (drinking identity) and with social pressure perception from important others (subjective norm) associated with positive motives (enhancement and social motives). Interestingly, these psychosocial reasons can be considered as “positive” to promote BD. Specifically, students underline direct (enhancement and social motives, respectively related to having fun and enjoying good times with friends) and indirect (subjective norm and drinking identity, respectively related to social valorization by peers and self-valorization) psychological benefits. In this line of reasoning, practicing BD would be “socially rational” from an inter-individual point of view. Future research could thus benefit from a deeper understanding of BD using psychosocial theories, as they specifically address these inter-individual processes and issues. For example, the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (Chung & Rimal, 2016) proposes to deepen normative influences interactions among variables such as subjective norms, identity and outcome expectations (i.e., the evaluation of the consequences arising from such behaviors, Bandura, 1997).

Second, the identification of the major psychological factors related to BD should impact the development of upcoming prevention protocols. Identifying the factors that are most associated with the recommended health behaviors can help to identify health promotion targets (Bandura, 2000), especially if cognitions related to these factors can be modified using simple intervention (see Webb & Sheeran, 2006 for a meta-analysis). In this line of reasoning, this research supports our understanding of the efficiency of programs specifically targeting some of the main variables associated to BD. For instance, motivational interviewing, which has been identified as being one of the most efficient type of brief alcohol interventions among young adults (Tanner-Smith & Lipsey, 2015), is usually structured by a set of different components such as alcohol consumption assessment, feedback on misuse risks, norms, information on potential harms, coping strategies and goal-setting plans for dealing with drinking situations. These prevention procedures clearly address one of the four decisive factors emphasized in the present study, namely the norm. However, the three other major factors (i.e., enhancement and social motives, and drinking identity) highlighted here did not elicit such an interest yet. This study underlines the necessity to develop new prevention programs that specifically target these major psychological factors related to BD among students. Current programs could benefit from including additional prevention modules tested in randomized controlled trial (e.g., addition of a module dealing with the decisional balance; Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006). With a framing technique associated with short-term perspective (Mollen, Engelen, Kessels, & van den Putte, 2017), it would be possible to counteract the perception of enhancement and social motives. And most of all, a possible promising path to deal with drinking identity could be to explore the benefits of a multicategorization process (see Crisp & Hewstone, 2007 for a review) that would weaken students' problematic consumer identity.

5. Limitations

First, regarding the measures relative to drinking identity, as this factor can be considered as an illustration of the dynamic interplay between personal identity (e.g., Lindgren et al., 2016) and social identity (e.g., Frings, Melichar, & Albery, 2016), further studies may gain in clarity by using more specific measures enabling the distinction between these two dimensions. Second, other positional variables that were not assessed in the current study such as family education level, income, immigration status or race/ethnicity could have play a role and could be investigated in future studies. Third, despite the limitations of traditional methods addressed by the dominance analysis, conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, assessing statistically the dominance of a variable is complex, and “no” true measure yet exists. Research on dominance analysis is still in its early stages (Johnson & LeBreton, 2004). Further, the weakness in the association between variables, as evidenced by a dominance analysis approach, in cross-sectional research does not preclude the role of these variables in behavioral change over time (see for instance: Tighe & Schatschneider, 2014). Therefore, further studies could be conducted in order to investigate the stability or not of the present findings through advancing years. Nevertheless, by demonstrating the usefulness of assessing the importance of a variable for a better addictive behaviors understanding, the present study may contribute to the growing interest in this method and its further improvement. Fourth, more general limitations can be considered. On the one hand, the self-reported nature of the survey potentially generated the recall and social desirability biases classically associated with such explorations. However, our results on socio-normative measures strongly suggest that binge drinkers do not refer to the general social desirability norms (i.e., prescribing a regulated and reasonable alcohol use) but rather to their peers as a reference group. Moreover, the anonymous nature of internet surveys might have at least partly reduced the social desirability bias. A complementary argument is that a recent research (Weigold, Weigold, & Russell, 2013, study 2) confirmed that methodologies inducing no contact between experimenter and participants lead to equivalent results than in-lab studies. On the other hand, in complement to the cross-sectional nature of our design, further longitudinal studies would be necessary to conclude on the causality between the identified factors and BD behavior. Finally, this study was particularly focused on the core psychological factors known to be related to BD. Of course, non-psychological factors, such as genetic (e.g., Wahlstrom, McChargue, & Mackillop, 2012) or psychophysiological (Bauer & Ceballos, 2014) factors, may be also kept in mind when approaching BD issues.

6. Conclusion

The systematic and simultaneous measure of key determinants of BD allowed to further understand BD practices by identifying four major psychological factors: enhancement motives, drinking identity, and further alcohol subjective norm, and social motives. Since BD behaviors seem to be primarily motivated by inter-individual factors, social psychology research could bring a more active contribution to further understand BD. On the whole, this research offers new avenues at the empirical level, by spotting the psychological determinants that should be more thoroughly explored, but also at the clinical level, to elaborate new prevention strategies focusing on these specific determinants.

Role of funding sources

This research was made possible by a grant from the Fondation pour la Recherche en Alcoologie (FRA) and the academic support of Unicaen. FRA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jessica Mange: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis, Visualization. Maxime Mauduy: Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis, Visualization. Cécile Sénémeaud: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Virginie Bagneux: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. Nicolas Cabé: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Denis Jacquet: Methodology. Pascale Leconte: Writing - review & editing. Nicolas Margas: Conceptualization. Nicolas Mauny: . Ludivine Ritz: Methodology, Project administration. Fabien Gierski: Resources, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Hélène Beaunieux: Methodology, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gwenaël Le Meur and Jérôme Gallot for their precious IT collaboration, Pauline Rasset for editing excel variables, Celine Quint and Anne-Pascale Le Berre for the English proofreading of this manuscript and Pierre L. Maurage for his stimulating discussion in general and in particular on this paper.

Footnotes

Age was used as a selection criterion because people under 30 are the population considered as being the most involved in BD (Reich, Cummings, Greenbaum, Moltisanti, & Goldman, 2015).

For each substance (cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, medicines or heroine), the participants had to provide a binary answer regarding their consumption (no vs. yes). Information collected is included in Fig. 2 to qualify the sample profile.

This rate is in line with the classical response rate related to internet surveys in the University of Caen Normandy (since 2016, eight surveys were sent to the student community; mean response rate = 15.94%; SD = 9.77) and ii) is higher than in most previous studies focusing on French University students (e.g., 7.07%, Tavolacci et al., 2013).

As only 27 participants indicated that French language was not their native language, this variable will not be further considered.

Sub-scores details associated with each question are provided as a complementary information in Table 1. Further, the weightings applied were from Townshend and Duka (2005), who based their calculation on Mehrabian and Russell (1978).

References

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf.

- Azen R., Budescu D.V. The dominance analysis approach for comparing predictors in multiple regression. Psychological methods. 2003;8(2):129. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). The anatomy of stages of change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 8–10. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of Social Cognitive Theory. In: Abraham In C., Norman P., Conner M., editors. Understanding and changing health behaviour: From health beliefs to self-regulation (Harwood Academic. Psychology Press; 2000. pp. 299–339. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer L.O., Ceballos N.A. Neural and genetic correlates of binge drinking among college women. Biological Psychology. 2014;97:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Carbin M.G. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Rochat L., Ceschi G., Carré A., Offerlin-Meyer I., Defeldre A.-C.…Van der Linden M. Validation of a short French version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(5):609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bø R., Billieux J., Landrø N.I. Binge drinking is characterized by decisions favoring positive and discounting negative consequences. Addiction Research & Theory. 2016;24(6):499–506. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2016.1174215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Carey K.B. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(3):331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce P., Bruce A., Gedeck P. and Python; O’Reilly Media: 2020. Practical Statistics for Data Scientists: 50+ Essential Concepts Using R. [Google Scholar]

- Callero P.L. Role-identity salience. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1985;48:203–215. doi: 10.2307/3033681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K.B., Carey M.P., Maisto S.A., Henson J.M. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell A.J., Bond R., Duka T., Morgan M.J. Further evidence of the heterogeneous nature of impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;76:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A., Rimal R.N. Social norms: A review. Review of Communication Research. 2016;4:1–28. doi: 10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2016.04.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A., Tran C., Weiss A., Caselli G., Nikčević A.V., Spada M.M. Personality and alcohol metacognitions as predictors of weekly levels of alcohol use in binge drinking university students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(4):537–540. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M.L. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp R.J., Hewstone M. Multiple social categorization. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;39:163–254. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2601(06)39004-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce, J. M., Toomey, T. L., Lenk, K., Nelson, T. F., Kilmer, J. R., & Larimer, M. E. (2018). NIAAA’s College alcohol intervention matrix: CollegeAIM. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 39(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/PMCID: PMC6104959. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Grace G.-R., Joshi P., Pelletier R. L’Échelle de solitude de l’Université Laval (ÉSUL): Validation canadienne-française du UCLA Loneliness Scale. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. 1993;25(1):12–27. doi: 10.1037/h0078812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini K.S., Carey K.B. Optimizing the use of the AUDIT for alcohol screening in college students. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(4):954–963. doi: 10.1037/a0028519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doise, W. (1982). L’explication en psychologie sociale. PUF.

- Ehret, P. J., Ghaidarov, T. M., & LaBrie, J. W. (2013). Can you say no? Examining the relationship between drinking refusal self-efficacy and protective behavioral strategy use on alcohol outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 38(4), 1898–1904. https://doi.org/doi: 10. 1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frings D., Melichar L., Albery I.P. Implicit and explicit drinker identities interactively predict in-the-moment alcohol placebo consumption. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2016;3:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gache P., Michaud P., Landry U., Accietto C., Arfaoui S., Wenger O., Daeppen J.-B. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening tool for excessive drinking in primary care: Reliability and validity of a French version. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(11):2001–2007. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187034.58955.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierski F., Spada M.M., Fois E., Picard A., Naassila M., Van der Linden M. Positive and negative metacognitions about alcohol use among university students: Psychometric properties of the PAMS and NAMS French versions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;153:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grömping U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo. Journal of statistical software. 2006;17(1):1–27. doi: 10.18637/jss.v017.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grömping U. Estimators of relative importance in linear regression based on variance decomposition. The American Statistician. 2007;61(2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger M.S., Anderson M., Kyriakaki M., Darkings S. Aspects of identity and their influence on intentional behavior: Comparing effects for three health behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(2):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James G., Witten D., Hastie T., Tibshirani R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning. 2014;Vol. 103 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.W., LeBreton J.M. History and use of relative importance indices in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7(3):238–257. doi: 10.1177/1094428104266510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Kuntsche S. Development and validation of the drinking motive questionnaire revised short form (DMQ–R SF) Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(6):899–908. doi: 10.1037/t17250-000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannoy S., Billieux J., Poncin M., Maurage P. Binging at the campus: Motivations and impulsivity influence binge drinking profiles in university students. Psychiatry Research. 2017;250:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannoy S., Mange J., Leconte P., Ritz L., Gierski F., Maurage P., Beaunieux H. Distinct psychological profiles among college students with substance use: A cluster analytic approach. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;109(october) doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren K.P., Ramirez J.J., Olin C.C., Neighbors C. Not the same old thing: Establishing the unique contribution of drinking identity as a predictor of alcohol consumption and problems over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30(6):659–671. doi: 10.1037/adb0000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Agley J., Hendryx M., Gassman R., Lohrmann D. Risk patterns among college youth: Identification and implications for prevention and treatment. Health Promotion Practice. 2015;16(1):132–141. doi: 10.1177/1524839914520702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurage P., Lannoy S., Mange J., Grynberg D., Beaunieux H., Banovic I.…Naassila M. What we talk about when we talk about binge drinking: Towards an integrated conceptualization and evaluation. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2020;55(5):468–479. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian A., Russell J.A. A questionnaire measure of habitual alcohol use. Psychological Reports. 1978;43(3):803–806. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1978.43.3.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollen S., Engelen S., Kessels L.T., van den Putte B. Short and sweet: The persuasive effects of message framing and temporal context in antismoking warning labels. Journal of Health Communication. 2017;22(1):20–28. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1247484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Dillard A.J., Lewis M.A., Bergstrom R.L., Neil T.A. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimon K.F., Oswald F.L. Understanding the results of multiple linear regression: Beyond standardized regression coefficients. Organizational Research Methods. 2013;16(4):650–674. doi: 10.1177/1094428113493929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich R.R., Cummings J.R., Greenbaum P.E., Moltisanti A.J., Goldman M.S. The temporal “pulse” of drinking: Tracking 5 years of binge drinking in emerging adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(3):635–647. doi: 10.1037/abn0000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rise J., Sheeran P., Hukkelberg S. The role of self-identity in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40(5):1085–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00611.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler M.S., Vasilenko S.A., Lanza S.T. Age-varying associations between substance use behaviors and depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;157:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.H., Hong H.G., Jeon S.-M. Personality and alcohol use: The role of impulsivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada M.M., Wells A. Metacognitive beliefs about alcohol use: Development and validation of two self-report scales. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(4):515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C., Gorsuch R., Lushene R., Vagg P., Jacobs G. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Strine T.W., Mokdad A.H., Dube S.R., Balluz L.S., Gonzalez O., Berry J.T.…Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with obesity and unhealthy behaviors among community-dwelling US adults. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith E.E., Lipsey M.W. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;51:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavolacci M.P., Ladner J., Grigioni S., Richard L., Villet H., Dechelotte P. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(724):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe E.L., Schatschneider C. A dominance analysis approach to determining predictor importance in third, seventh, and tenth grade reading comprehension skills. Reading and writing. 2014;27(1):101–127. doi: 10.1007/s11145-013-9435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townshend J.M., Duka T. Patterns of alcohol drinking in a population of young social drinkers: A comparison of questionnaire and diary measures. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2002;37(2):187–192. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townshend J.M., Duka T. Binge drinking, cognitive performance and mood in a population of young social drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(3):317–325. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000156453.05028.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townshend J.M., Kambouropoulos N., Griffin A., Hunt F.J., Milani R.M. Binge drinking, reflection impulsivity, and unplanned sexual behavior: Impaired decision-making in young social drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(4):1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/acer.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallentin-Holbech L., Rasmussen B.M., Stock C. Effects of the social norms intervention The GOOD Life on norm perceptions, binge drinking and alcohol-related harms: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2018;12:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVeen J.W., Cohen L.M., Watson N.L. Utilizing a multimodal assessment strategy to examine variations of impulsivity among young adults engaged in co-occurring smoking and binge drinking behaviors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127(1–3):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga S., Piko B.F. Being lonely or using substances with friends? A cross-sectional study of Hungarian adolescents’ health risk behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1107):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2474-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A.C., Toomey T.L. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:206–225. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlstrom L.C., McChargue D.E., Mackillop J. DRD2/ANKK1 TaqI A genotype moderates the relationship between alexithymia and the relative value of alcohol among male college binge drinkers. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2012;102(3):471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb T.L., Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(2):249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigold A., Weigold I.K., Russell E.J. Examination of the equivalence of self-report survey-based paper-and-pencil and internet data collection methods. Psychological Methods. 2013;18(1):53–70. doi: 10.1037/a0031607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]