Abstract

Glycocalyces are the pericellular coat of glycoproteins, glycolipids, and proteoglycans. Yet the exploration of glycocalyx function is still ongoing because of the availability of investigative tools capable of discerning the function of one component without inflicting collateral changes in the organization/function of other constituents. The current report by Ramnath et al. explores the function of one family of molecules, the syndecans, as potential regulators of endothelial cell glycocalyx thickness in normal and diabetic glomeruli.

Glycocalyces are a complex pericellular layer projecting from cell surfaces outward toward the microenvironment. Although the mo-lecular composition of the protein and carbohydrate components comprising the glycocalyx has been explored over the past several decades, the organization of glycocalyces and regulation of their structure have been difficult to discern in vivo for different reasons. For example, in the case of mesangial cells, which are embedded within basement membrane–like extracellular matrix, it is almost impossible to discern by routine methods where the pericellular glycocalyx ends and the matrix begins. One would surmise that in the case of podocytes and endothelial cells, whose apical surfaces face fluid-phase micro-environments, glycocalyces would be reasonably easy to resolve. However, routine fixation/tissue processing methods have adverse effects on glycocalyx structure, more often than not resulting in a disruption of the native architecture/organization of the pericellular coat.

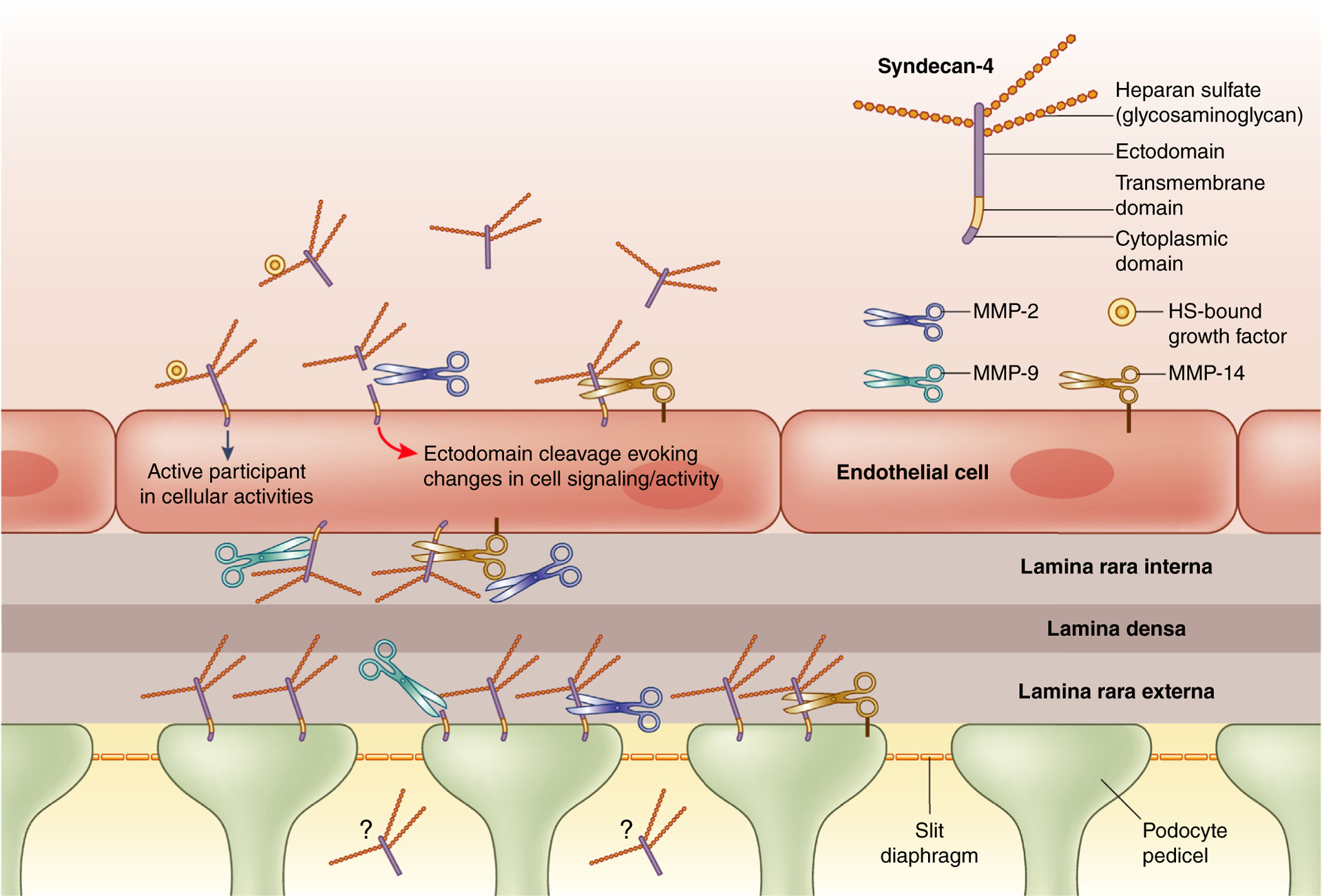

Syndecans (Sdc) are one set of mo-lecular components participating in the formation of the pericellular endothelial glycocalyx.1 Sdcs consist of a 4-member family of single-pass transmembrane proteoglycans whose ectodomains, projecting outward from the cell surface, bear heparan and/or chon-droitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains (Figure 1).2,3 Although the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tails of the 4 Sdc family members share a reasonably high degree of homology, the ectodomains of the Sdc family members are dissimilar in amino acid sequence, size, and position of their glycosaminoglycan chains. One must view the biology of the Sdcs in a holistic manner, for the Sdc core proteins and their glycosaminoglycan chains each have their own intrinsic bioactivities. A recent evaluation of the Sdc inter-actome2 indicates that approximately 67% to 71% of the currently known interactions between Sdc family members and their respective partners are mediated via their glycosaminoglycan chains. Given this point of reference, one could support the rather simplistic view that a vital function of Sdc core proteins is to place the highly bioactive glycosaminoglycan chains in the right place, at the right time.

Figure 1 |. The cartoon depicts the potential distribution of syndecan(s) on endothelial and podocyte surfaces in the glomerular capillary.

For clarity the endothelial fenestrae are not shown. The localization and 1 major function of syndecan-4 on the basal surfaces of cells has been well-described in the literature.2 Syndecans, via sulfate motifs, present in heparan sulfate (HS) chains, engage matrix components, which comprise the glomerular basement membrane (e.g., laminin and type IV collagen). Syndecan-4, when engaged to matrix molecules in this manner, works alongside integrins as a co-receptor, evoking downstream intracellular events that affect cellular signaling functions and/or behaviors. The metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-14) are all capable of cleaving syndecan core proteins at several different sites along the length of the protein core2,3 yielding proteolytic fragments of variable sizes. All 3 MMPs do target regions of syndecan-4 that are relatively membrane-proximal, removing most of the ectodomain (with attached glycosaminoglycan chains) portion of the molecule. Proteolytic cleavage of basally located syndecans in this manner would disrupt the interactions between syndecan-4 and its basement membrane ligands, potentially affecting intracellular signaling. In addition, since heparan sulfates are capable of sequestering growth factors, cytokines, etc., proteolytically cleaved syndecan-4 ectodomain (apical or basal) would also cause a loss of the pericellular pool of these molecules into the microenvironment. Although one would surmise that the shed syndecan-4 found in the plasma would potentially arise from the apically located syndecan-4 on endothelial cells, what is uncertain is the origin of the shed syndecan-4 found in the urine. Work from our laboratory has demonstrated that podocytes express syndecan-4 at the level of the pedicel, which could be 1 source of urinary syndecan-4 fragments.

The functions of the Sdcs have been traditionally associated with growth factor sequestration/presentation to their cognate receptors, mediation of cell signaling, and actively participating in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. Most recently, Sdcs have been associated with other activities such as regulation/modulation of TRPC (transient receptor potential channel) function and identified as active participants in exo-some biogenesis.2

Because of the influence of Sdcs (whether direct or indirect) to intracellular signaling pathways, cells have evolved several mechanisms to regulate cell surface bioavailability of functional Sdcs. Such mechanisms include: endo-cytotic processes that remove the entire molecule from the surface4; the lytic actions of carbohydrate lyases, such as heparanases, to trim the overall length of the glycosaminoglycan chains, and sulfatases that deconstruct critical sulfate patterns, which are known to be necessary for the bioactivity of heparans, along the length of the heparan chain.5 In addition, the actions of proteases, such as plasmin, thrombin, metzincins (matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs]), ADAMS (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase), or ADAMTS (ADAMS having thrombospondin domains), are capable of cleaving Sdc core proteins, permitting them to be shed from the cell surface (Figure 1).2,3,6 The latter process has been explored over the past 2 decades, and numerous proteolytic cleavage sites for Sdc 1, 2, and 4 have been identified. Because of the sequence dissimilarity among the Sdc ectodomains, the distribution of proteolytic cleavage sites along the length of the Sdc core proteins differs significantly, leading to the generation of cleavage fragments whose sizes are both core protein specific and protease specific.

The report by Ramanth et al.7 used the MMP inhibitor, MMPI (2-[(4-biphenylsulfonyl)amino]-3-phenylpropionic acid), an orally active, small molecule inhibitor of MMP2 and MMP9, to ameliorate changes in the thickness of the glomerular endothelial cell glycocalyces that develop in an animal model of type 1 diabetes mellitus. The rationale for this intervention was that the authors noted, as have others, an increase in active MMP2 and MMP9 levels in kidney cortical lysates, plasma, and urine. In turn, when comparing glomerular endothelial cell glycocalyx thickness between untreated and treated diabetic animals, a 1.6-fold increase in glycocalyx thickness and a 2-fold increase in glycocalyx coverage in the glomerular endothelium of MMPI-treated animals were seen. A similar response was noted, but not measured, for podocyte glycocalyces, which were also labeled by the experimental methods. A corresponding decrease (2-fold) in the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio was seen in the MMPI-treated animals compared with untreated animals.

How does Sdc4 fit into the picture? During the course of the study the authors measured a 1.6-fold reduction of Sdc4 protein expression in the glomeruli from diabetic versus control animals. A 1.8-fold increase in plasma Sdc4 protein levels and an 11.8-fold increase in urinary Sdc4 protein levels in specimens taken from diabetic versus control animals was also seen. The authors further verified the decrease in endothelial Sdc4 abundance in vivo using an intravital labeling approach for Sdc4 with monoclonal antibody KY/8.2 directed against residues 1 to 71 of the Sdc4 ectodomain. Intervention with MMPI appeared to correct many of the changes, leading to the resto-ration of Sdc4 (1.8-fold increase vs. untreated) levels in the glomeruli of MMPI-treated diabetic animals. A 2-fold decrease in the measurement of plasma levels of Sdc4 levels in MMPI-treated diabetic animals versus untreated was also noted, suggesting that MMPI intervention was able to halt MMP2/9 Sdc4 shedding activity. Surprisingly, MMPI intervention did not change the release of shed Sdc4 into the urine.

The report from Ramanth et al. reveals a number of very important observations about how the underlying pathophysiology present in diabetes mellitus drives augmented Sdc4 shedding via the enhanced activities of MMP2/9. Much of the data presented in this current study are consistent with data from earlier investigations reported by the Satchell laboratory. However, the downstream effects of Sdc4 shedding have not been fully elucidated in this circumstance, with the study data showing association rather than causation.

An additional conundrum (i.e., the elephant in the room) is the question: if the presence of Sdc4 in the endothelial glycocalyx is critical to maintain the integrity of the endothelial glycocalyx, then why don’t the Sdc4 knockout mice in general develop significant proteinuria?8

Discerning the downstream effectors/effects of Sdc4 shedding in this system could prove to be an extremely difficult task because of the overall promiscuous nature of the Sdc inter-actome, the interactions mediated by both the core protein and its attached glycosaminoglycan chains comprising a diverse grouping of molecules.2 More-over, the fact that Sdcs participate at the cell surface in multiple lateral interactions with other entities adds yet another layer of complexity to the system. One could speculate that such lateral interactions, potentially ternary in nature, could be at the root of the effects seen on the glycocalyx as the result of Sdc4 shedding. Using STORM (stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy), Fan et al.9 recently demonstrated the surface distribution of cell surface heparan sulfate (the glycosaminoglycan attached to Sdcs) and hyaluronan, another key glycosaminoglycan found in the glycocalyx. Their report showed a hexagonal weave-like network of hyaluronan elements at the endothelial cell surface with heparan sulfate– positive clusters present at the weave intersections. Given the fact that the presence of hyaluronan was recently shown to be critical for the normal function of the endothelial glycocalyx,10 if the hyaluronan weave is mediated via a ternary interaction with Sdcs via an unknown binding partner, then Sdc shedding could have consequences on the global organization of the endothelial glycocalyx.

So the question still remains: participant or bellwether?

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The author declared no competing interests.

Editor’s Note

The Editors invite you to also read the letters to the editor by Comper and Ramnath, in this issue, devoted to the same paper by Ramnath et al. as this commentary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marki A, Esko JD, Pries AR, Ley K. Role of the endothelial surface layer in neutrophil recruitment. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:503–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gondelaud F, Ricard-Blum S. Structures and interactions of syndecans. FEBS J. 2019;286: 2994–3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manon-Jensen T, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR. Mapping of matrix metalloproteinase cleavage sites on syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 ectodomains. FEBS J. 2013;280:2320–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christianson HC, Belting M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan as a cell-surface endocytosis receptor. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond E, Khurana A, Shridhar V, Dredge K. The role of heparanase and sulfatases in the modification of heparan sulfate proteoglycans within the tumor microenvironment and opportunities for novel cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2014;4:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 2010;277:3876–3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramnath RD, Butler MJ, Newman G, et al. Blocking matrix metalloproteinase-mediated syndecan-4 shedding restores the endothelial glycocalyx and glomerular filtration barrier function in early diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;97: 951–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Echtermeyer F, Thilo F, et al. The proteoglycan syndecan 4 regulates transient receptor potential canonical 6 channels via RhoA/Rho-associated protein kinase signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan J, Sun Y, Xia Y, et al. Endothelial surface glycocalyx (ESG) components and ultra-structure revealed by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Biorheology. 2019;56:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Berg BM, Wang G, Boels MGS, et al. Glomerular function and structural integrity depend on hyaluronan synthesis by glomerular endothelium. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1886–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]