Abstract

Background:

The Purdue Pegboard test (PPT) assesses upper-extremity dexterity and motor skills. We hypothesized that PPT skill would predict functional and cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease (PD), independent of observer-rated measures of motor impairment.

Methods:

We utilized data from 399 PD participants enrolled in the Deprenyl and Tocopherol Antioxidative Therapy of Parkinsonism (DATATOP) trial. Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) metrics, neuropsychological assessments, and clinical rating scales were extracted for analysis with multivariate linear mixed-effects (LME) and generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression models.

Results:

In multivariate logistic regression, higher baseline and time-varying PPT scores predicted better visual processing speed and attention throughout longitudinal follow-up. No similarly strong associations were found for tests of memory, non-visual attention, phonemic fluency, or set-shifting. Independently of observer-rated motor impairment (UPDRS part III), PPT performance was significantly associated with changes in activities of daily living (ADL) function measured with UPDRS part II. Low baseline PPT score (≤10th percentile) doubled the relative risk of later ADL dysfunction (≥90th percentile).

Conclusions:

PPT impairment selectively predicted declining psychomotor processing speed in PD. The domain-specificity of this association may reflect correlated pathophysiological changes in top-down visual and motor control pathways. PPT also predicted increasing ADL dysfunction after adjusting for objective measures of motor impairment. We suggest that PPT scores may be prognostically useful for predicting cognitive changes and ADL dysfunction, which have dramatic impacts on both patient and caregiver quality of life. Furthermore, simple task-based assessments like the PPT could be investigated for remote assessment in PD.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, functional impairment, Purdue pegboard test, cognitive domains, visual processing, cognitive impairment, neuropsychological tests

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative condition and is diagnostically linked to motor impairment (tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability).1 There is also increasing appreciation for the varied non-motor symptoms experienced by persons with PD, which include cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, depression, anxiety, and sleep and perceptual disturbances.2, 3 Motor impairment that reduces independence in activities of daily living (ADL) and the presence of non-motor symptoms are both critical determinants of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in PD.4, 5 Furthermore, cognitive impairment and ADL dysfunction are two of the most important determinants of caregiver duress and the need for nursing home placement in PD.6 Therefore, prognostic indicators of these developments may be useful for understanding trajectories of HRQoL and independence.

Many prior studies of risk factors for cognitive decline in PD have focused on predicting the onset of dementia or reaching a cutoff on a ‘global’ screening measure such as the mini-mental status exam (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). However, due to the heterogeneity of PD and its differential impacts on cognitive domains,7 it is also important to understand the specific aspects of cognition to which putative biomarkers are relevant. This may inform our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, as well as our ability to anticipate incipient cognitive decline and counsel patients accordingly.

Simple functional assessments that are easy to administer and interpret are increasingly attractive options for monitoring PD progression. The Purdue Pegboard test (PPT) is a neuropsychological test that measures manual dexterity and visuomotor coordination.8, 9 Low PPT score has been cross-sectionally associated with reduced MoCA performance in PD10 and poor PPT score may portend an increased risk for dementia in PD11 However, these studies did not investigate domain-specific cognitive changes predicted by PPT. Additionally, these studies did not statistically adjust for motor impairment, making it unclear whether the PPT offers prognostic value beyond that of observer-rated motor deficits. In the present study, we accounted for these and other issues while assessing the predictive value of PPT score for several cognitive tests in the well-characterized Deprenyl and Tocopherol Antioxidative Therapy of Parkinsonism (DATATOP) trial.12 We also hypothesized that because the PPT represents a unified functional metric of sensorimotor integration, attention, and manual dexterity, lower PPT scores would also predict ADL dysfunction after adjusting for observer-rated motor impairment.

Methods

DATATOP study documents and data were provided by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) through the Archived Clinical Research Datasets program. These data are available to qualified researchers pending an approved request. DATATOP enrolled patients with de novo PD in a multicenter trial coordinated by the Parkinson Study Group (PSG); extensive study documentation is readily available in prior publications12 DATATOP was approved by the IRB of each participating site and written informed consent was provided by all participants.

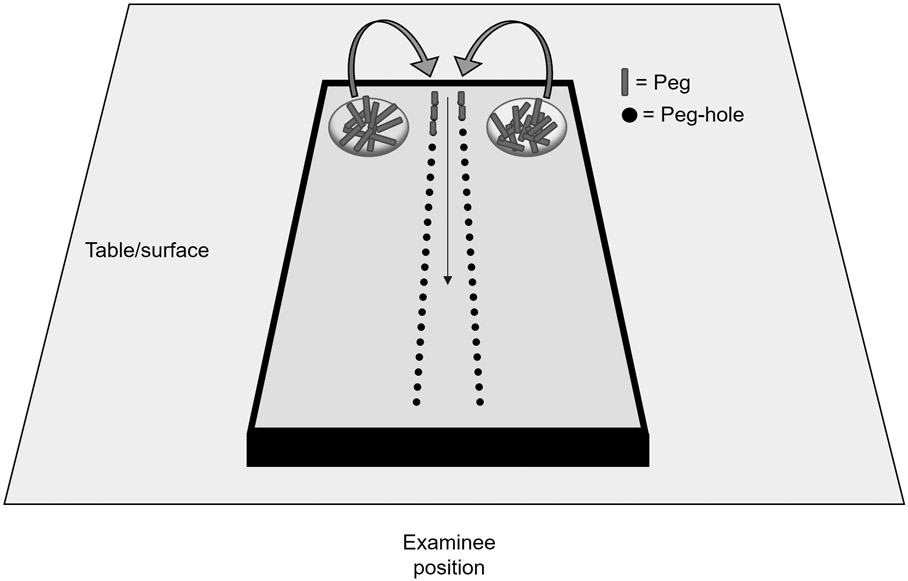

We extracted demographic and clinical participant data including PPT scores and cognitive test results. A schematic of the PPT task is provided in Figure 1. Participants are given 30 seconds to complete the test, in which both hands are used to sequentially move as many small metal pegs as possible (maximum of 50) into two parallel rows of small holes arranged orthogonal to the examinee. Total score is the number of correctly loaded pegs at the end of the trial. The UPDRS parts II and III were used for ADL function and motor impairment scales, respectively. The cognitive tests included were: the Symbol Digit Modalities (SDMT), a test of visual attention and visual processing speed in which the participant uses a key to convert visually presented symbols into numbers13; the backward Digit Span test (DST), a test of non-visual attention and working memory in which the participant must repeat a series of orally presented numbers in reverse order14; the Odd man out test, a set-shifting and rule inference task involving the identification of outlier patterns based on a classification rule that the participant must ascertain15; the Selective Reminding test, which assesses delayed recognition and delayed recall as measures of retention and retrieval 16; the Controlled Word Association test (COWAT), a test of phonemic fluency17; the New Dot test, a test of visuospatial discrimination and memory in which the participant must remember and recognize changes to a dot-pattern.18 To enable meaningful longitudinal analyses, participants were excluded if they lacked data for ≥ 2 visits or if follow-up data spanned fewer than one year. A total of 399 participants met these criteria. In the available data, follow-up duration ranged from 12 to 26 months (median 17 months).

Figure 1: Pegboard test schematic.

Participants are given 30 seconds to complete the test, in which both hands are used to sequentially move as many small metal pegs as possible (maximum of 50) into two parallel rows of small holes arranged orthogonal to the examinee. Total score is the number of correctly loaded pegs at the end of the trial.

All data analyses were conducted in R.19 Data were initially analyzed by linear mixed-effects (LME) models with cognitive test scores as continuous dependent variables. Model diagnostics suggested non-normal residual distribution for some cases, therefore we opted for a robust version of LME implemented in R through the package robustlmm.20 Robust LME regression weights observations on the basis of residual skew to negate outlier bias.20 Participant identifier was entered as the only random effect. The primary outcome for each model was the coefficient estimate (B) with 95% confidence intervals and p-value (two-tailed test, adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm method) for bimanual PPT score (range 0-24). LME models were adjusted for with the following fixed covariables: baseline outcome measure (cognitive test) score, age at enrollment, disease duration, Hoehn & Yahr stage, sex, education (years), UPDRS rigidity (q31-35), postural-instability (q46-47), postural tremor (q29-30), tremor (a20, c20, 24-28) and hand movement score (q36-41). In predictive baseline LME models, we used the values for these variables and PPT score at baseline, but follow-up scores for the dependent variable. In longitudinal time-varying LME models, the dependent and independent variables were temporally concordant (same visit).

In addition to robust LME model analysis, we performed a confirmatory secondary analysis with generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression models, with autoregressive correlation structures specified. GEE models do not assume a particular distribution of errors, which eliminates concerns over non-normal residuals as observed in non-robust LME models.21 Because GEE logistic regression accepts a binary outcome variable, we dichotomized cognitive test scores on the basis of impairment, which we defined as performance falling at or below the 10th percentile. Percentiles were defined using the distribution of scores among PD participants at the baseline DATATOP assessment. We used the 10th percentile to define “impairment” to ensure that the number of cases would be sufficient for multivariable regression. ORs were calculated as the exponentiated coefficients from the logistic regression output, with 95% confidence intervals calculated from the corresponding standard errors. The relative probabilities of cognitive test impairment for patients with and without PPT impairment were calculated by converting model-derived odds of cognitive impairment into probabilities with the formula (P = odds/(1+odds).22 As for LME models, p-values were based on a two-tailed test and were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm method. Independent variables were specified as described above for LME models. All GEE modeling was performed using the R package ‘geepack’.21 Robust GEE parameter and standard error estimates were selected for reporting. Where provided, relative risk calculations were performed in accordance with convention.23

Results

Because the study population of DATATOP has been extensively characterized, we have placed the baseline demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics summary data in a supplement (Table S1). Among the 399 participants, 268 (67.2%) were male and 227 (56.9%) were Hoehn & Yahr stage 1 or 1.5 at enrollment. The remaining 172 (43.1%) were stage 2 or 2.5. MMSE score was 28.8 ± 1.4 (mean ± SD) and ranged from 23-30. Bimanual PPT score was 8.2 ± 3.2, ranging from 1-24. UPDRS-III motor exam scores were 15.9 ± 8.5.

We first used robust LME regression to determine (1) whether PPT performance at baseline was predictive of later cognitive test scores, and (2) whether time-varying PPT score correlated significantly with cognitive test scores. LME results are summarized in Table 1. PPT score correlated strongly with SDMT over time, though baseline PPT performance was not statistically significant as a predictor of later SDMT scores throughout follow-up. PPT performance was not significantly predictive of—nor longitudinally correlated with— visuospatial discrimination/memory (New dot test), delayed recall or delayed recognition, phonemic fluency, non-visual attention (Digit Span test), or set-shifting (Odd Man Out test). In the SDMT models, the UPDRS motor exam score for hand movement items was also correlated over time with SDMT score (B = −0.27; 95% CI: −0.15 to −0.3940; unadjusted p<0.001) and as a predictive measure at baseline (B = −0.24; 95% CI: −0.46 to −0.02; unadjusted p=0.033). Postural instability, postural tremor, rigidity, and tremor subscores were not similarly associated.

Table 1:

Linear mixed-effects models for the effect of PPT score on cognitive scores

| Independent variable type |

Outcome variable |

B-coefficient | 95% CI (low) |

95% CI (high) |

Adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline PPT score | SDMT | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.139 |

| Phonemic fluency | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.39 | 0.326 | |

| Delayed recognition | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.322 | |

| Delayed recall | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.640 | |

| New dot | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.345 | |

| Digit-span | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.634 | |

| Odd-man-out | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.696 | |

| PPT score (time-varying) | SDMT | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.53 | < 0.001 |

| Phonemic fluency | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.33 | 0.548 | |

| Delayed recognition | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 1.000 | |

| Delayed recall | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 1.000 | |

| New dot | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.354 | |

| Digit-span | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 1.000 | |

| Odd-man-out | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.390 |

Two linear-mixed effects models were constructed for each cognitive test (dependent variable). For models measuring the effect of baseline PPT (score at enrollment) on cognitive test score over time, baseline values were also used for all other adjusting covariables. For the non-baseline models, the values at each follow-up assessment were used for all covariables. Baseline cognitive test score was used to adjust all models. B-coefficients (unstandardized coefficients) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) correspond to the relationship between bimanual PPT score (independent variable) and the indicated neuropsychological test. P-values for baseline and longitudinal models were separately adjusted using the Holm method, using the number of tests (7) as the number of multiple comparisons. Covariables adjusted for in all models include sex, education (years), age, disease duration, UPDRS III subsections (rigidity, postural tremor, postural instability, hand movements), and Hoehn & Yahr stage.

We noted that because the cognitive tests produce scores with different distributions, we considered that our LME models may have yielded false-negative results for the five tests that were not predicted by PPT score. We therefore designed GEE logistic regression models (Table 2) for each cognitive measure. In this context, low baseline PPT score (≤ 10th percentile) was still selectively predictive of worse SDMT performance after correction for multiple comparisons. However, PPT score correlated over time with both the SDMT and the COWA test of phonemic fluency.

Table 2:

GEE regression models for the effect of PPT score on cognitive impairment

| Independent variable type |

Outcome variable (≤ 10th percentile on indicated test) |

Odds ratio | 95% CI (low) |

95% CI (high) |

Adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline PPT score | SDMT | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.94 | 0.043 |

| Phonemic fluency | 0.85 | 0.71 | 1.02 | 0.439 | |

| Delayed recognition | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 0.535 | |

| Delayed recall | 0.97 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 1.000 | |

| New dot | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.01 | 0.436 | |

| Digit-span | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 1.000 | |

| Odd-man-out | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.000 | |

| PPT score (time-varying) | SDMT | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.021 |

| Phonemic fluency | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.020 | |

| Delayed recognition | 1.04 | 0.96 | 1.13 | 0.891 | |

| Delayed recall | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.06 | 1.000 | |

| New dot | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.521 | |

| Digit-span | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.08 | 1.000 | |

| Odd-man-out | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.103 |

Two GEE logistic regression models were constructed for each cognitive test (dependent variable). For models measuring the effect of baseline PPT (score at enrollment) on cognitive test score over time, baseline values were also used for all other adjusting covariables. For the non-baseline models, the values at each follow-up assessment were used for all covariables. Baseline cognitive test score was used to adjust all models. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) correspond to the relationship between bimanual PPT score and impaired cognitive test score (≤ 10th percentile). P-values for baseline and longitudinal models were separately adjusted using the Holm method, using the number of tests (7) as the number of multiple comparisons. Covariables adjusted for in all models include sex, education (years), age, disease duration, UPDRS III subsections (rigidity, postural tremor, postural instability, hand movements), and Hoehn & Yahr stage.

We next hypothesized that since the PPT requires complex visuomotor planning and manual dexterity, it would also have value for predicting overall daily functioning. Therefore, we used the UPDRS part II to quantify ADL dysfunction as the outcome in LME regression (Table 3). Interestingly, baseline PPT was a strong predictor when dichotomized at the 10th percentile, but not when retained as a continuous variable. However, PPT correlated with ADL longitudinally regardless of dichotomization. To explain this, we noted that at baseline, the relationship between ADL and PPT is non-linear and better described by a quadratic function (Figure 2). Analysis of covariance suggested that a quadratic model fit these data better than a linear model (df=1, F=23.2, p<0.0001), and the adjusted R2 values were 0.11 and 0.15 for univariable linear and quadratic models, respectively. However, this was not the case at the final participant evaluation, where no value for a second-order term was found (df=1, F = 0.01, p=0.91). Therefore, PPT is limited as a linear predictor of ADL in early PD, but poor performance is still useful for predicting ADL. To quantify this value, we calculated the relative risk of ADL impairment (UPDRS part II score ≥ 90th percentile), which was 2.3 (Z = 5.42; p<0.0001) for participants with baseline PPT impairment (≤ 10th percentile). After adjusting for UPDRS motor impairment (part III), Hoehn & Yahr stage, age, disease duration, and MMSE score in logistic regression, the relative risk remained fairly stable at 1.8 (corresponding OR = 2.7; 95% CI: 1.4–5.1; p = 0.003). Finally, we tested whether the cognitive measures available similarly predicted or correlated with ADL (Supplemental table S2). This analysis indicated that none of the seven cognitive assessments were significantly predictive of ADL decline as observed for the PPT. Interestingly, delayed recall did selectively correlate over time with ADL, though not as markedly as for the PPT.

Table 3:

Linear mixed-effects models for ADL prediction by PPT

| Independent variable | B-coefficient | 95% CI (low) |

95% CI (high) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| PPT score | −0.08 | −0.18 | 0.03 | 0.140 |

| PPT impairment | 2.18 | 1.08 | 3.28 | < 0.001 |

| Time-varying | ||||

| PPT score | −0.13 | −0.20 | −0.06 | < 0.001 |

| PPT impairment | 0.74 | 0.33 | 1.16 | < 0.001 |

Linear models were constructed with ADL score (UPDRS part II; higher is worse) as the outcome variable. PPT impairment was defined as a score ≤ 10th percentile. Baseline models measured the effect of baseline PPT on ADL over time and baseline values were also used for all other adjusting covariables. For the time-varying models, the values at each follow-up assessment were used for all covariables. Baseline ADL score was used to adjust all models. B-coefficients (unstandardized) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) correspond to the relationship between bimanual PPT score (independent variable) and ADL score. Covariables adjusted for in all models include sex, education (years), age, disease duration, UPDRS III subsections (rigidity, postural tremor, postural instability, hand movements), and Hoehn & Yahr stage.

Figure 2: Baseline PPT as a non-linear correlate of ADL function.

ADL function (UPDRS part II; higher is worse) as a function of PPT score at baseline (left panel) or the final evaluation (right panel) (n=399). Analysis of variance supported the superiority of the quadratic function (red dashed lines) over the linear function (black lines) at baseline (df=1, F=23.2, p<0.0001), but not at the final visit (df=1, F=0.01, p=0.91). Adjusted R2 values were 0.153 and 0.106 for the quadratic and linear models at baseline, respectively.

Discussion

Our findings support prognostic value for the PPT for assessing aspects of cognition and functional impairment in early de novo PD. Specifically, we found that the PPT is most pertinent to visual processing speed and attention, as assessed by the SDMT. Our models adjusted for age, disease duration, and specific motor impairments that could confound a relationship between PPT and test performance, including hand movement quality, postural instability, and disease severity (Hoehn & Yahr). This suggests that difficulty with the PPT portends cognitive decline even after adjusting for objective motor impairment and disease-specific metrics. Notably, our repeated-measures analyses adjusted for baseline cognitive test score, indicating that lower PPT scores remain dynamically correlated with worsening visual processing speed later in the disease. We also noted a longitudinal correlation between PPT and phonemic fluency when the latter variable was dichotomized at the 10th percentile, but baseline PPT did not predict worsening phonemic fluency after correction for multiple comparisons.

Low PPT scores were also associated with an approximately two-fold increase in the risk of becoming functionally disabled (UPDRS ADL score ≥ 90th percentile) during the 2-year duration of DATATOP evaluation. This was significant and stable after adjusting for UPDRS motor impairment, Hoehn & Yahr stage, age, disease duration, and MMSE score, suggesting that it is not confounded by overall disease severity or generalized cognitive decline. This supports the more general notion that skill-based or tool-based assessments may have predictive value that is not encapsulated by observer-rated or objective measures of motoric impairment. Tests like the PPT require fine cognitive control over motor processes, which likely explains its predictive association with both the SDMT and general functional impairment.

We did not identify significant correlations between PPT score and visuospatial discrimination (New dot test), non-visual attention (Digit-span test) or generalized executive function (Odd man out test). This suggests that our cognitive findings are specific to attention and processing speed in the context of visual stimulus processing, as tested by the SDMT. Therefore, reduced manual dexterity and speed in the functional, task-based context of the PPT may portend declining speed at which visual information can be processed and/or assigned value in a top-down manner. The fact that adjusting for motor impairment or disease severity does not eliminate this predictive association suggests that the PPT exhibits dissociable predictive value unique to tests of visuospatial processing.

The SDMT taxes frontoparietal and fronto-occipital networks involved in attention and top-down visual processing.24 Low PPT performance may be an early marker of dysfunction in this attentional system, or a more general marker for declining top-down cognitive control over complex goal-directed behaviors. Pathology in frontostriatal circuitry is an important factor in the cognitive dysfunction of early PD,25-27 suggesting that frontal network dysfunction may be underlie the connection between SDMT and PPT performance changes. Because DATATOP enrolled participants not yet exposed to dopaminergic agents, this finding is also not confounded by complications of therapy and may more accurately reflect the cognitive-motor deficits inflicted by PD. However, we acknowledge that the current study is not equipped to mechanistically inform the correlation between PPT skill and SDMT score. Additionally, DATATOP did not recruit non-PD controls. This limits the generalizability of our analyses, as we could not investigate utility for the PPT outside of the PD population.

Given the need for functional assessments that provide prognostically useful information in PD, our findings support further exploration of the PPT or similar task-based tests. In 2014, the PDEDGE task force—commissioned by the Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy to study effective outcome measures in PD—recommended the PPT for monitoring PD through Hoehn & Yahr stages 2-4. It also strongly recommended a similar test of manual dexterity, the nine-hole peg test, which may be preferable to the PPT due to lower cost. Future studies would be required to investigate which tests are most cost-effective and informative in the PD population.

PD is increasingly recognized to be a profoundly heterogeneous disorder,28 which reinforces the need to understand the specific deficits patients are at risk for. Our findings build upon and clarify previous research that suggested a potential link between PPT performance and cognition, but did not provide descriptions of how it may relate to specific cognitive domains.11 We suggest that future studies address the real-world utility of the PPT or similar tests in the context of remote care. Our current findings are limited by the relatively limited follow-up duration in the NINDS DATATOP dataset. Therefore, replication of our findings in a dataset or study spanning a longer total follow-up would also be of benefit. Similarly, it would be interesting to know whether the findings reported herein would replicate in a study of elderly individuals without a diagnosis of PD, as cognitive impairment and ADL dysfunction are not unique to PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors report no pertinent conflicts of interest. J.T.H. receives stipend support through the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (NIH/NIGMS T32GM007309) and the National Institute on Aging (F30AG067643). G.M.P reports consultation for Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosures / Conflict of Interest statement

The present study was supported by the Parkinson Study Group and the Parkinson’s Foundation Advancing Parkinson’s Treatments Innovations Grant.

References

- 1.Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, et al. Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017;3:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E. The Neuropsychiatry of Parkinson Disease: A Perfect Storm. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019;27:998–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schapira AHV, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2017;18:435–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller B, Assmus J, Herlofson K, Larsen JP, Tysnes OB. Importance of motor vs. non-motor symptoms for health-related quality of life in early Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, Chaudhuri KR, Group NV. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2011;26:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Tandberg E, Laake K. Predictors of nursing home placement in Parkinson's disease: a population-based, prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Neuropsychological and clinical heterogeneity of cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology 2010;9:1200–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desrosiers J, Hebert R, Bravo G, Dutil E. The Purdue Pegboard Test: normative data for people aged 60 and over. Disabil Rehabil 1995;17:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiffin J, Asher EJ. The Purdue Pegboard: norms and studies of reliability and validity. J Appl Psychol 1948;32:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu MT, Szewczyk-Krolikowski K, Tomlinson P, et al. Predictors of cognitive impairment in an early stage Parkinson's disease cohort. Mov Disord 2014;29:351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anang JB, Gagnon JF, Bertrand JA, et al. Predictors of dementia in Parkinson disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology 2014;83:1253–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoulson I DATATOP: A decade of neuroprotective inquiry. Ann Neurol 1998;44:S160–S166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith A Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler D A standardized memory scale for clinical use. J Psychol 1945;19:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flowers KA, Robertson C. The effect of Parkinson's disease on the ability to maintain a mental set. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985;48:517–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 1974;24:1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benton AL, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination: Manual of instruction. Iowa City: University of Iowa, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albert M, M M. The assessment of memory disorders in patients with Alzheimer's disease. In: L S, ed. Neuropsychology of memory. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1984: 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- 19.R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Version 3.6.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koller M robustlmm: An R Package for Robust Estimation of Linear Mixed-Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software 2016;75:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R Package geepack for Generalized Estimating Equations. Journal of Statistical Software 2006;15/2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton EC, Dowd BE, Maciejewski ML. Odds Ratios-Current Best Practice and Use. JAMA 2018;320:84–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva PHR, Spedo CT, Baldassarini CR, et al. Brain functional and effective connectivity underlying the information processing speed assessed by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Neuroimage 2019;184:761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owen AM, James M, Leigh PN, et al. Fronto-striatal cognitive deficits at different stages of Parkinson's disease. Brain 1992;115 ( Pt 6):1727–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams-Gray CH, Evans JR, Goris A, et al. The distinct cognitive syndromes of Parkinson's disease: 5 year follow-up of the CamPaIGN cohort. Brain 2009;132:2958–2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams-Gray CH, Foltynie T, Brayne CE, Robbins TW, Barker RA. Evolution of cognitive dysfunction in an incident Parkinson's disease cohort. Brain 2007;130:1787–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg D, Postuma RB, Bloem B, et al. Time to redefine PD? Introductory statement of the MDS Task Force on the definition of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:454–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.