Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors blocking programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) have emerged as effective treatment options for cancer. However, immunotherapy is only effective in a subset of patients. Identifying effective biomarkers to predict the treatment response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors remains an unmet clinical need.

Methods

This study retrospectively analyzed clinical information and genetic profiling results of 16,013 samples from Chinese patients with various cancer types in order to investigate the prevalence of CD274 (also known as PD-L1) amplification in various cancer types and its association with existing PD-1/PD-L1 biomarkers, including tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and PD-L1 expression.

Results

Amplification of CD274 was identified in 174 samples with an overall prevalence of 1.09% among all cancer types in the cohort. The prevalence of CD274 amplification in different cancer types and histological subtypes of lung cancer was varied, with cervical cancer having the highest prevalence. Distinct distributions of TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression between CD274-amplified and wild-type samples were observed in several cancer types as well as among different histological subtypes of lung cancer.

Conclusions

Although CD274 amplification was only observed in a small proportion of patients, it demonstrated an association with TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression in several common cancer types. The molecular features of CD274 in different cancer types are heterogeneous. The role of CD274 amplification as a novel biomarker of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors remains to be characterized in future prospective clinical studies.

Keywords: CD274, PD-L1, gene amplification, predictive biomarker, pan-cancer analysis

Introduction

The treatment options for cancer have expanded with the increasing number of emerging clinical techniques and therapies. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are able to block programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and are an effective treatment approach for various hematologic malignancies and solid tumors (1). Therefore, immunotherapies with a PD‐1/PD‐L1 blockade action have been recognized and approved by regulatory authorities in many different countries. Numerous studies have reported that cancer patients receiving immunotherapy demonstrate a higher response rate and more durable remission (2). However, immunotherapy is only effective in a subset of patients. Identifying which patients are most likely to respond to, and benefit from, cancer immunotherapy remains an unmet clinical need.

PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor mutational burden (TMB) have been shown to have a clinically significant association with the treatment efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapies (3-6). Currently, they are used to predict treatment response. In addition to existing biomarkers, CD274 (also known as PD-L1) gene amplification is emerging as a potential novel biomarker for PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapies. The amplification of CD274 is characterized by copy number (CN) alterations located at the 9p24.1 locus. It was initially observed among patients with certain subtypes of lymphomas (7). More than half of the patients harboring CD274 amplification exhibited a high susceptibility to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapies (7).

However, the role of CD274 in solid tumors remains undefined due to limited data and studies. The two retrospective studies in U.S populations surveyed a wide variety of cancer types and reported that CD274 amplification occurred in a small subset (0.7% and 0.72%, respectively) of patients (8,9). The objective response rate for these patients was 66.7%, with a median progression-free survival of 15.2 months (8). Another study performed with a Chinese population reported a CD274 amplification rate of 3.79% across several common cancer types (10). Given the heterogeneous nature of cancer, the role of CD274 amplification as an immunotherapy biomarker among different populations may also vary and is worthy of further characterization.

In the present study, we performed an extensive analysis of CD274 amplification and its association with other well-known biomarkers for immunotherapies, including TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression in more than 10,000 tumor samples from Chinese patients with over 24 cancer types. We also performed an in-depth analysis of the common tumor types in the cohort and the different histological subtypes of lung cancer. We present the following article in accordance with the REMARK reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-853).

Methods

Patients and samples

The study included patients who were diagnosed with malignant solid tumors and had undergone comprehensive genomic profiling. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples or plasma from the patients were sent to Burning Rock Biotech laboratory (Guangzhou, China), which is a College of American Pathologists (CAP)-accredited and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified clinical laboratory for genetic profiling. The gene panels used in the present study consisted of either 168 genes (Lung Plasma, Burning Rock Biotech, China) or 520 genes (OncoScreen Plus, Burning Rock Biotech, China). Both panels cover the same genomic regions of CD274. The demographic, clinical, and genetic profiling information of the patients were retrospectively collected from a de-identified database. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wuxi People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

DNA extraction

The QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used to extract circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma and the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, UK) were used to extract tumor DNA from FFPE samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Qubit 2.0 fluorometer and the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) were used to measure DNA concentration.

Library construction and sequencing

DNA was sheared to fragments with M220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA), and then was subjected to end repair, phosphorylation and adaptor ligation. The Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) were used to select DNA fragments with a range of 200–400 bp. Then, capture probe baits for hybridization, magnetic beads for hybrid selection, and PCR amplification were applied. Two commercially available panels covering 168 genes (Lung Plasma) or 520 genes (OncoScreen Plus) were used to capture sequencing targets. DNA quality and fragment size were assessed by Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA). Samples with index were subjected to paired-end sequencing on Illumina NextSeq 500 (Illumina, Inc., Hayward, CA, USA).

Sequence data analysis

The paired-end reads were mapped to the human genome (hg19) by a Burrows-Wheeler aligner v.0.7.10 (11). Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) v.3.2 (12) and VarScan v.2.4.3 (13) was used to optimize local alignment, call and annotate variants. Factera v.1.4.3 (14) was used to perform DNA translocation analysis. The VarScan filter pipeline was used to filter variants in which loci with depths less than 100 were filtered out. Sequencing results from matched white blood cells were used to filter out germline mutations of the sample. At least eight supporting reads were required for calling single nucleotide variations (SNV) and at least five supporting reads were required for calling insertion-deletion variations (INDEL). Variants were grouped as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and were excluded for further analysis if their frequencies in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), 1,000 Genomes, dbSNP, and ESP6500SI-V2 databases exceeded 0.1%. The remaining variants were annotated with ANNOVAR (2016-02-01 release) (15) and SnpEff v.3.6 (16).

CNV calling

The in-house analysis scripts were used to detect CNVs. Briefly, potential sequencing bias in the coverage data due to guanine and cytosine (GC) content and probe design were corrected. The coverage of different samples was normalized to comparable scales according to the average coverage of all captured regions. The copy number was calculated for each capture interval based on the ratio between the coverage depth in the tumor sample and the reference coverage which is the average coverage of adequate samples (n>50) without CNV. CNV in gene was called if the coverage data of the gene region was significantly different from reference. The following criteria were applied for CNV calling: (I) if more than 60% coverage of the genes capture intervals were significantly different from the reference. The z-test was used when comparing coverage of each capture interval with mean interval coverage of control samples (P<0.005 for hotspot genes and P<0.001 for others); (II) if the copy number exceeded the threshold for copy number gain (CN >2.25 for hotspot genes and CN >2.5 for others) and copy number loss (CN <1.75 for hotspot genes and CN <1.5 for others).

CtDNA, which is tumor-derived fragmented DNA released by apoptotic or necrotic cancer cells, only constitutes a very small fraction of cell-free DNA (released by normal cells) and usually ranges from 0.01% to 0.1%. Numerous studies, including our internal data, have shown that more than 50% of mutations identified from plasma have an allelic frequency of less than 1%. Therefore, ultra-deep sequencing is necessary to identify mutations from plasma. The range of an average sequencing depth of 5,000×–20,000× is a well-established criterion for plasma genotyping. Matched white blood cells were used for germline mutation filtering. An average of 20,000× sequencing depth was achieved. Mutational allelic frequency (MAC) is the frequency of a variant in a defined population, expressed as a percentage. In this context, MAF is the percentage of a specific variant detected from plasma.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were presented as mean or median scores. The categorical variables were presented as frequencies. The unpaired Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare continuous variables, while two-sided Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables where appropriate. The statistically significant threshold was P value <0.05. All bioinformatics analyses were performed with R (v.3.5.3, the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Cohort characteristics

The study was performed on 16,013 tumor samples from patients with over 24 different cancer types. The gender ratio between male and female was 1.15 (8,339/7,241). The mean and median ages were 58.73 and 60 years old, respectively. Lung cancer accounted for 56.94% (9,118/16,013) of the total samples and was the most common cancer type. Other common types included in the cohort were breast cancer (8.89%, 1,423 samples), colorectal cancer (7.66%, 1,226 samples), gastroesophageal cancer (4.81%, 770 samples), and ovarian cancer (2.55%, 409 samples) (Figure S1).

The lung cancer samples were further divided by histological subtype. They consisted of 66.96% adenocarcinoma (6,105/9,118), 12.27% squamous cell carcinoma (1,119/9,118), 2.76% small cell lung cancer (252/9,118), 0.42% large cell lung cancer (38/9,118), 0.41% neuroendocrine tumor (37/9,118), and 17.19% consisted of others with an unidentified subtype (1,567/9,118).

Distribution of CD274 amplification

In total, amplification of CD274 was identified in 174 samples, including 107 samples of lung cancer, 17 samples of breast cancer, 8 samples of gastroesophageal cancer, 6 samples of ovarian cancer, and 6 samples of cervical cancer. Single cases with positive CD274 amplification were identified in kidney cancer, melanoma, bladder cancer, sarcoma, and renal pelvis cancer. The overall positive rate of CD274 amplification in the cohort was 1.09% (174/16,013). The rates of CD274 amplification among different cancer types varied. As shown in Figure 1A, cervical cancer showed the highest rate of CD274 amplification (3.26%, 6/184), followed by head and neck cancers (2.78%, 4/144). For common types in the cohort, positive rates of CD274 amplification were 1.17% for lung cancer (107/9,118), 1.19% for breast cancer (17/1,423), 0.24% for colorectal cancer (3/1,226), 1.04% for gastroesophageal cancer (8/770), and 1.47% for ovarian cancer (6/409).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of CD274 amplification. (A) CD274 amplification in common cancer types; (B) CD274 amplification in different histological subtypes of lung cancer.

In lung cancer, CD274 amplification was identified in 0.77% (47/6,105) of adenocarcinoma, 2.77% (31/1,119) of squamous cell carcinoma, 1.98% (5/252) of small cell lung cancer, and 7.89% (3/38) of large cell lung cancer samples. CD274 amplification was not identified in neuroendocrine tumor samples. The prevalence of CD274 amplification varied among different subtypes of lung cancer (P<0.05). Compared with adenocarcinoma, large cell lung cancer and squamous cell carcinoma showed significantly higher percentages of CD274 amplification (P<0.05, Figure 1B). Although large cell lung cancer showed the highest rate of CD274 amplification (7.89%), there were only 38 samples therefore this rate may not be representative of real-world data.

Distribution of TMB and mutant gene profiles

The mean and median levels of TMB in all analyzed samples were 5.87 and 3.64 mutations per mega base (Mb), respectively. For the 174 samples with CD274 amplification, the mean and median levels of TMB were 9.95 and 6.36 mutations/Mb, respectively. It was observed that TMB levels in the CD274-amplified samples were significantly higher than in the wild-type samples (P<0.001). However, when the TMB data were adjusted for maximum allele frequency (max AF), only marginally significant differences in TMB levels were observed between the two groups (P=0.0542). As shown in Figure 2A, although TMB levels between samples with amplified CD274 and wild type vary among different cancer types, no significant differences were observed except for lung cancer (P<0.001), gastroesophageal cancer (P<0.01), and kidney cancer (P<0.05). In lung cancer, the TMB level was higher in CD274-amplified samples than in wild-type samples (Figure 2A, P<0.001). The mean and median TMB levels in the CD274-amplified samples were 10.18 and 8.18 mutations/Mb, compared with 5.46 and 3.64 mutations/Mb in the CD274 wild-type samples, respectively. A subgroup analysis of TMB in lung cancer indicated that only adenocarcinoma showed a significantly different TMB level between CD274 amplification and wild type (Figure 2B). In lung adenocarcinoma, the mean and median TMB levels in CD274-amplified samples were 10.53 and 6.36 mutations/Mb, compared with 4.67 and 2.73 mutations/Mb in CD274 wild-type samples, respectively. In other histological subtypes of lung cancer (Figure 2B), there were no significant differences in TMB levels between CD274-amplified and wild-type samples.

Figure 2.

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) levels in CD274 amplification group and wild type. (A) Comparison in common cancer types; (B) comparison in different histological subtypes of lung cancer. The levels of TMB are indicated with logarithmic transformation in the vertical axis. The P value is indicated with asterisks. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

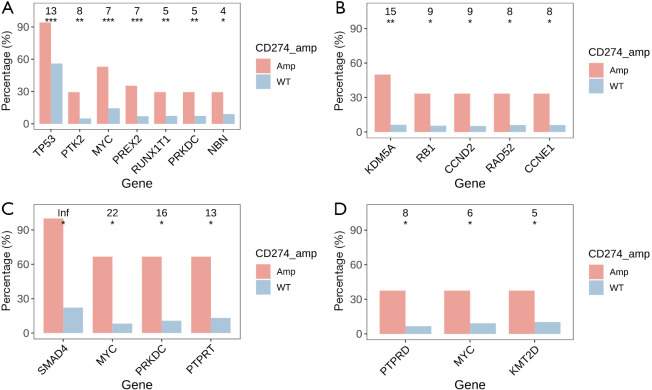

The profiles of gene mutations among different cancer types were heterogeneous. The present study observed a significant association of gene mutation rates with CD274 amplification in common cancer types. Signatures of mutant genes with a mutation rate >5% in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastroesophageal cancer, and ovarian cancer are shown in Figure 3. There were 7 genes in breast cancer, 4 genes in colorectal cancer, 3 genes in gastroesophageal cancer, and 5 genes in ovarian cancer that showed significantly higher mutation rates in CD274 amplification samples than in wild type samples. In lung cancer, 24 genes showed a higher mutation rate in samples with CD274 amplification while mutation of the EGFR gene was more often identified in CD274 wild-type samples. The signatures of mutant genes also varied among different histological subtypes. Fourteen genes in adenocarcinoma, 14 genes in squamous cell carcinoma, 4 genes in small cell lung cancer, and 6 genes in large cell lung cancer showed significantly higher mutation rates in samples with CD274 amplification than in wild type (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of mutant genes in other common cancer types of the cohort. (A) Breast cancer; (B) ovarian cancer; (C) colorectal cancer; and (D) gastroesophageal cancer. The numbers at the top reflect the effect size of each mutant gene indicated by odds ratio (OR). Inf: OR with positive infinity. The P value is indicated with asterisks. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Figure 4.

Distribution of mutant genes in lung cancer. (A) All samples of lung cancer; (B) adenocarcinoma; (C) squamous carcinoma; (D) small cell lung cancer; and (E) large cell lung cancer. Numbers at the top reflect the effect size of each mutant gene indicated by odds ratio (OR). Inf: OR with positive infinity. The P value is indicated with asterisks. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Distribution of MSI

In the present study, MSI status was available in approximately 85% of samples from the cohort (13,585/16,013). The vast majority of analyzed samples were microsatellite stable (MSS, 99.02%, 13,453/13,585). There were 124 samples with MSI-H (0.91%). Of the 149 samples with CD274 amplification, only two samples were MSI-H: one sample of lung cancer (0.96%, 1/104) and one sample of gastroesophageal cancer (16.67%, 1/6). In samples with CD274 wild type, 0.18% of samples of lung cancer (14/7,648) and 2.96% of samples of gastroesophageal cancer (18/608) were MSI-H. In addition, 4.99% of samples of colorectal cancer (50/1,003), 1.78% of samples of ovarian cancer (6/337), and 0.72% of samples of cervical cancer (1/139) were MSI-H in CD274 wild type (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of MSI in common cancer types.

| Cancer types | CD274 amp − | CD274 amp + | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSS* | MSI-H* | MSI-H* (%) | Total | MSS* | MSI-H* | MSI-H* (%) | Total | ||

| Lung cancer | 7,634 | 14 | 0.18 | 7,648 | 103 | 1 | 0.96 | 104 | |

| Breast cancer | 1,133 | 0 | 0 | 1,133 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | |

| Cervical cancer | 138 | 1 | 0.72 | 139 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Gastroesophageal cancer | 590 | 18 | 2.96 | 608 | 5 | 1 | 16.67 | 6 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 331 | 6 | 1.78 | 337 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Head and neck cancers | 126 | 0 | 0 | 126 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Sarcoma (non-GIST**) | 232 | 0 | 0 | 232 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Bladder cancer | 58 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 953 | 50 | 4.99 | 1,003 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Kidney cancer | 121 | 0 | 0 | 121 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 75 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

*, the status of microsatellite instability (MSI) was indicated as microsatellite stable (MSS) and microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H); **, sarcomas exclude of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

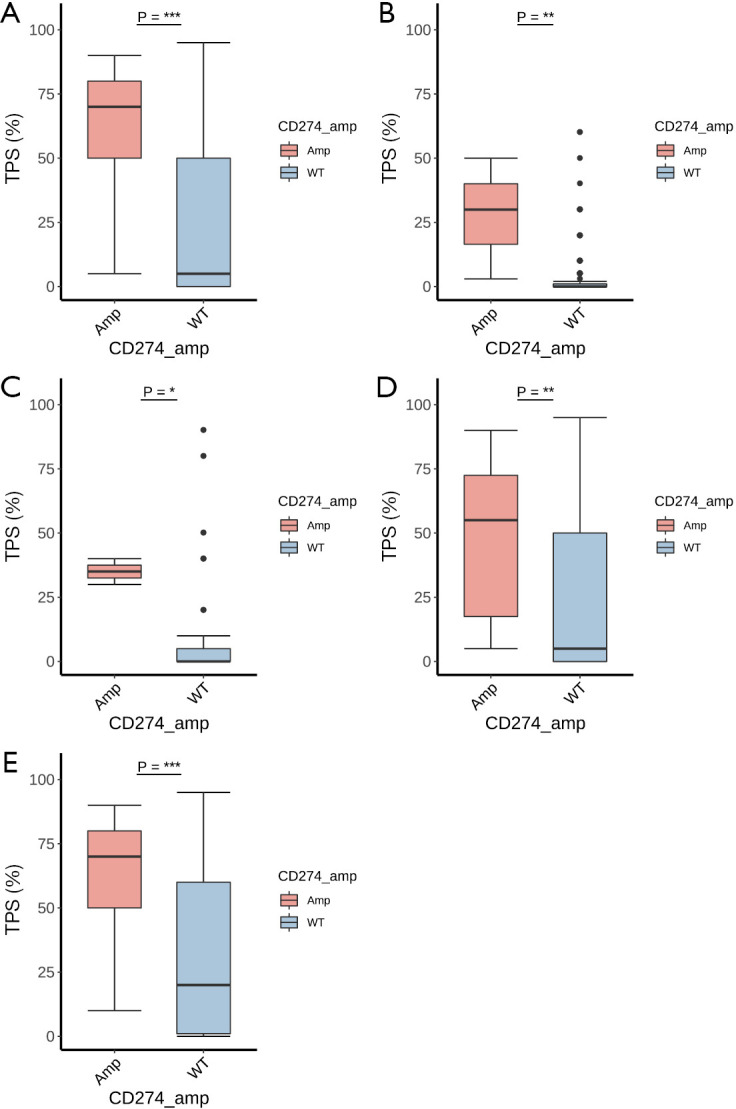

Distribution of PD-L1 expression

PD-L1 expression was available in 2,683 samples of the cohort (16.76%), including 40 samples with CD274 amplification and 2,643 samples with wild-type CD274. In lung cancer, breast cancer, and gastroesophageal cancer, a significantly higher level of PD-L1 expression was observed in the CD274 amplification group than in the wild-type group (Figure 5). In lung cancer, there were 29 samples in the CD274 amplification group with a mean TPS of 59.48 and a median TPS of 70, which was significantly higher than that of the 1707 samples in the wild-type group, which had a mean TPS of 25.07 and a median TPS of 5 (P<0.001). A subgroup analysis of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the lung also indicated a higher expression level of PD-L1 in the CD274 amplification samples than in the wild-type samples (P<0.01 and 0.001, respectively).

Figure 5.

Association of CD274 amplification with PD-L1 expression in different cancer types. (A) Lung cancer; (B) breast cancer; (C) gastroesophageal cancer; (D) lung cancer (adenocarcinoma) and (E) lung cancer (squamous carcinoma). The PD-L1 expression is indicated by the tumor proportion scores (TPS). The P value is indicated with asterisks. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Discussion

The development of immunotherapies via PD‐1/PD‐L1 blockade has shown promising treatment responses for various cancer types. However, several clinical studies have indicated that only a limited proportion of patients may benefit from PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors. Significant efforts have been undertaken to develop predictive biomarkers, including TMB (3), MSI (4), and PD-L1 expression (5,6), in order to identify appropriate patients for PD‐1/PD‐L1 immunotherapy. In addition, amplification of the CD274 gene has also been proposed as a novel biomarker for patients receiving immunotherapy.

In this study, we performed a pan-cancer analysis of CD274 amplification in a Chinese population sample spanning more than 24 cancer types. The overall prevalence of CD274 amplification in the study cohort was 1.09% among all cancer types, which is consistent with previous findings indicating that CD274 amplification occurs in a small subset of malignant tumors (8). The prevalence and distribution of CD274 amplification reported by previous studies are varied and may be explained by the different compositions of cancer types in different cohorts. A US population study reported an overall prevalence of CD274 amplification of 0.7% (8). Tumor types with a higher percentage of CD274 amplification included mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (10.5%), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (3.1%), lung squamous cell carcinoma (1.7%), and breast carcinoma (1.9%) (8). In another US study, the overall prevalence of CD274 amplification was 0.72 and the highest prevalence of CD274 amplification was identified in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (3.2%), uterine cervix cancer (2.1%), and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (2.0%) (9). Meanwhile, a Chinese study reported that CD247 was amplified in 3.79% of analyzed samples, and CD247 amplification most frequently occurred in lung squamous cell carcinoma and HER2‐positive breast cancer (10). In our study, cervical cancer showed the highest percentage of CD274 amplification (3.26%). Similar to other studies, we also observed a higher prevalence of CD274 amplification in head and neck cancers (2.78%).

The present study analyzed the distribution of established predictive biomarkers such as TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression for immunotherapies. Among all cancer types, the mean TMB was 5.87 mutations/Mb and the median TMB was 3.64 mutations/MB, which is slightly lower than the US cohort study that reported a mean TMB of 7.9 mutations/Mb and a median TMB of 3.8 mutations/Mb (9). TMB levels appear to vary according to different cancer types. Higher TMB levels in lung cancer and colorectal cancer have been reported in a Chinese population (10), whereas higher TMB levels in melanoma, lung cancer, and urothelial carcinoma have been reported in a US population (9). TMB was also associated with the amplification of CD274. It was reported that mutational load was higher in CD274-amplified samples (17). In our study, the mean TMB of the CD274-amplified and wild-type samples were 9.95 vs. 5.83 mutations/Mb (P<0.05), respectively. The medians were 6.36 vs. 3.64 mutations/Mb for the CD274-amplified and wild-type samples, respectively (P<0.05). In most cancer types in the present study, TMB levels trended higher in the CD274-amplified samples than the wild-type samples, but no statistically significant differences were observed except for lung cancer, gastroesophageal cancer, and kidney cancer. Our study also identified heterogeneous signatures of mutant genes between CD274 amplification and wild-type groups. Common oncogenes such as P53 and MYC showed a higher proportion of mutations in the CD247-amplified samples among various cancer types.

In our study, more than half of the samples were lung cancer, in particular adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The overall prevalence of CD274 amplification in lung cancer was 1.17%, but it varied among different subtypes. In adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, the prevalence of CD274 amplification was 0.77% and 2.77%, respectively (P<0.001). Previous studies have reported the prevalence of CD274 amplification in different subtypes of lung cancer ranging from 0.6% to 14.29% (18-22), which might be influenced by different populations and sample sizes. In CD274-amplified patients with NSCLC, improved survival outcomes with nivolumab monotherapy have been observed (21). Our study also evaluated TMB across different subtypes of lung cancer. Lung adenocarcinoma showed significantly higher TMB levels in CD274-amplified samples than wild-type samples (median TMB 6.36 vs. 2.73 mutations/Mb, P<0.05). CD274-amplified lung adenocarcinoma patients were more likely to harbor mutations in the following genes: TP53, PTPRD, and MET. For squamous cell carcinoma, there were no significant differences in TMB levels between CD274-amplified and wild-type samples (median TMB 8.18 vs. 7.27 mutations/Mb, P>0.05). The TMB of lung squamous cell carcinoma has been reported in other studies with a median level of 9.43 mutations/Mb (23), and genetic mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung have been frequently identified in P53, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, and SOX2 (24).

In addition, this study also performed an analysis of other biomarkers including MSI and PD-L1 expression. The overall prevalence of MSI-H in our study was 0.91% which was lower than previous studies that reported a prevalence of 4% in a Chinese population sample (10) and 1.9% in a US population sample9. This finding might be explained by the high proportion of lung cancer samples in the present cohort. MSI varied widely among different cancer types. A study of MSI across 39 cancer types indicated that 0.53% of lung adenocarcinoma and 0.60% of lung squamous cell carcinoma were MSI-H which were lower than other common cancer types (25). In our study, colorectal cancer showed the highest proportion of MSI-H which was consistent with previous studies (9,10). None of the identified MSI-H colorectal cancer patients harbored CD274 amplification. The analysis of PD-L1 expression indicated that samples with CD274 amplification showed a significantly higher level of PD-L1 expression in lung cancer (P<0.001), breast cancer (P<0.01), and gastroesophageal cancer (P<0.05). This finding was consistent with previous studies indicating that CD274 amplification was associated with an increased expression level of PD-L1 (20). The underlying mechanisms of PD-L1 upregulation might be associated with the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (22).

There were several limitations in our study, including potential sampling bias and the retrospective design of the study. Our study included cancer patients receiving NGS-based genetic profiling according to their physicians’ recommendations. The distribution of cancer types in the study cohort was also unbalanced. More than half of the samples were lung cancer, while other cancer types may not have been adequately represented. Therefore, the prevalence and distribution of CD274 amplification and other biomarkers might not be representative of some cancer types with limited sample sizes. As a retrospective study, detailed treatment and follow-up information were limited in the cohort. The application of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and survival outcomes in patients with CD274 amplification remains unknown.

Conclusions

The present study performed a comprehensive analysis of CD274 amplification with existing biomarkers of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors including TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression in various cancer types. Although CD274 was amplified in a small proportion of patients, distinct distributions of TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression between CD274 amplification and wild-type groups were observed in several cancer types. The heterogeneous molecular features of CD274 in different cancer types should be investigated in prospective clinical studies to confirm the role of CD274 amplification as a novel predictive biomarker of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, their families, and the medical and research staff who participated in this study.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wuxi People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the REMARK reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-853

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-853

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-853). YZ, JX, CC, and TH are employees of Burning Rock Biotech. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: D. Fitzgerald)

References

- 1.Boussiotis VA. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1767-78. 10.1056/NEJMra1514296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardhan K, Anagnostou T, Boussiotis VA. The PD1:PD-L1/2 Pathway from Discovery to Clinical Implementation. Front Immunol 2016;7:550. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden as an Independent Predictor of Response to Immunotherapy in Diverse Cancers. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16:2598-608. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509-20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 2015;14:847-56. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis AA, Patel VG. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker: an analysis of all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother cancer 2019;7:278. 10.1186/s40425-019-0768-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2010;116:3268-77. 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman AM, Piccioni D, Kato S, et al. Prevalence of PDL1 amplification and preliminary response to immune checkpoint blockade in solid tumors. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1237-44. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang RSP, Haberberger J, Severson E, et al. A pan-cancer analysis of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry and gene amplification, tumor mutation burden and microsatellite instability in 48,782 cases. Mod Pathol 2021;34:252-63. 10.1038/s41379-020-00664-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zang Y sheng, Dai C, Xu X, et al. Comprehensive analysis of potential immunotherapy genomic biomarkers in 1000 Chinese patients with cancer. Cancer Med 2019;8:4699-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1754-60. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297-303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 2012;22:568-76. 10.1101/gr.129684.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman AM, Bratman SV, Stehr H, et al. FACTERA: a practical method for the discovery of genomic rearrangements at breakpoint resolution. Bioinformatics 2014;30:3390-3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:e164. 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012;6:80-92. 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budczies J, Bockmayr M, Denkert C, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of copy number changes in programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1, CD274) - associations with gene expression, mutational load, and survival. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2016;55:626-39. 10.1002/gcc.22365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George J, Saito M, Tsuta K, et al. Genomic amplification of CD274 (PD-L1) in small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:1220-6. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, Mori K, et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy number gains in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7:32113-28. 10.18632/oncotarget.8528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clavé S, Pijuan L, Casadevall D, et al. CD274 (PDL1) and JAK2 genomic amplifications in pulmonary squamous-cell and adenocarcinoma patients. Histopathology 2018;72:259-69. 10.1111/his.13339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, Nishimoto K, et al. Evaluation of Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Gene Amplification and Response to Nivolumab Monotherapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw open 2020;3:e2011818. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda S, Okamoto T, Okano S, et al. PD-L1 Is Upregulated by Simultaneous Amplification of the PD-L1 and JAK2 Genes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:62-71. 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang T, Shi J, Dong Z, et al. Genomic landscape and its correlations with tumor mutational burden, PD-L1 expression, and immune cells infiltration in Chinese lung squamous cell carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:75. 10.1186/s13045-019-0762-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto T, Takada K, Sato S, et al. Clinical and Genetic Implications of Mutation Burden in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Lung. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:1564-71. 10.1245/s10434-018-6401-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as