Abstract

Asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus are prevalent during pregnancy and associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. The risk of gestational diabetes mellitus is increased with asthma, and more severe asthma; yet, the underlying mechanisms are unknown. This review examines existing literature to explore possible links.

Asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus are associated with obesity, excess gestational weight gain, altered adipokine levels and low vitamin D levels; yet, it’s unclear if these underpin the gestational diabetes mellitus–asthma association. Active antenatal asthma management reportedly mitigates asthma-associated gestational diabetes mellitus risk. However, mechanistic studies are lacking.

Existing research suggests asthma management during pregnancy influences gestational diabetes mellitus risk; this may have important implications for future antenatal strategies to improve maternal-fetal outcomes by addressing both conditions. Addressing shared risk factors, as part of antenatal care, may also improve outcomes. Finally, mechanistic studies, to establish the underlying pathophysiology linking asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus, could uncover new treatment approaches to optimise maternal and child health outcomes.

Keywords: Asthma, pregnancy, gestational diabetes, maternal health

Introduction

Chronic medical conditions can complicate pregnancy and increase the risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are the most common, affecting up to 12.7%1 and 14.3%2 of pregnant women in Australia, respectively. Notably, asthma is associated with an increased risk of GDM.3–6 Their interaction may be causally related and modifiable, raising the possibility that treating these conditions can improve pregnancy outcomes.

A 2014 meta-analysis reported a 39% increased relative risk (RR) of GDM in women with, compared to women without, asthma (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17–1.66, n = 19 cohort studies).4 Among four studies that adjusted for covariates, the odds of GDM amongst women with asthma was 66% higher than women without asthma (odds ratio (OR) 1.66, 95% CI 1.53–1.79).4 Moreover, the risk was higher with moderate to severe, versus mild, asthma (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.06–1.33, n = 3 studies),4 but mitigated with active asthma management (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.81–1.46, n = 7 studies).4 However, no research has explored underlying mechanisms linking asthma and GDM.

Asthma and GDM are independently associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes including preterm birth, neonatal hospitalisation, respiratory distress and perinatal mortality.7–10 However, whether the presence of both conditions increases the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, above the risk conferred by either alone, is unknown. There are also long-term adverse maternal and offspring health outcomes associated with both conditions.8,9,11–13 Thus, optimising asthma management, preventing GDM, and maintaining euglycemia during pregnancy, is ideal to promote maternal and offspring health.

An understanding of the pathogenesis linking maternal asthma and GDM is needed to direct research in this area. Thus, this review will examine current knowledge regarding the association, and explore the underlying pathophysiology, that may link these conditions.

Potential links between asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus

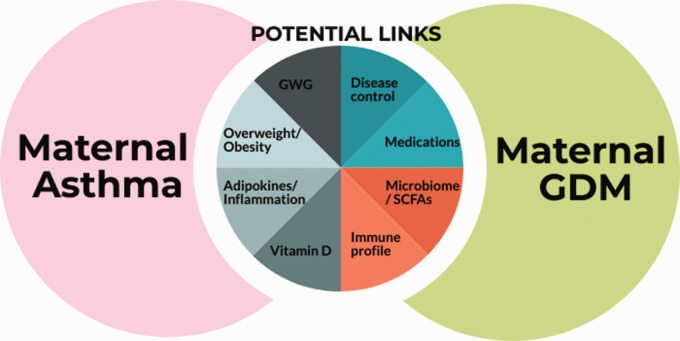

Several factors may link asthma and GDM, notably weight status and weight gain during pregnancy, alterations in adipokines and inflammatory mediators, suboptimal vitamin D levels and/or asthma management (Figure 1). While a complex interplay likely exists, for simplicity, these factors are explored separately.

Figure 1.

Factors potentially underlying the association between maternal asthma and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). GWG: gestational weight gain; SCFAs: short chain fatty acids.

Of note, alterations in the T-cell profile,14 and the composition of the gut microbiota and short chain fatty acid metabolism,15 may be implicated in the GDM-asthma association; however, this is outside the scope of this review.

Obesity

Estimated rates of obesity during pregnancy in women from the USA, UK and Australia range from 18% to 31.8%,16,17 reaching 53.7% in low-income women in the USA.16 Obesity is associated with increased risks, including early pregnancy loss, pre-eclampsia, a large-for-gestational age (LGA) infant and congenital anomalies.16 Furthermore, obesity imparts increased risk for metabolic syndrome and asthma/wheeze in offspring.16,18

The prevalence of GDM increases with each body mass index (BMI) category.8 A meta-analysis of 20 cohort studies found that overweight, obesity and severe obesity increased the risk of GDM by 2, 4 and 8 times, respectively, compared to healthy-weight women.19 A recent meta-analysis of individual patient data (IPDMA; 265,270 singleton births) estimated that approximately 43% of GDM was attributable to maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity,20 demonstrating BMI is a strong determinant of GDM.

A higher proportion of pregnant women with asthma are overweight or obese, compared to pregnant women without asthma.21,22 Our group found 32.3% and 40.2% of pregnant women with asthma were overweight and obese, respectively, with approximately half experiencing an exacerbation(s) requiring medical intervention, compared to 25% of non-overweight women.23 An earlier study reported a 30% increased odds of an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy in the presence of obesity (95% CI 1.1–1.7).21 Recently, we found obesity during pregnancy reduced the effectiveness of biomarker-based clinical asthma management on exacerbations (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.59, 95% CI 0.32–1.08).24 Thus, obesity is a major problem affecting women with asthma.

The associated increased GDM risk may be mediated via higher levels of obesity, and inferred adiposity and associated metabolic alterations, in women with asthma. In support, a previous study found that several adverse events in pregnancy, including GDM, were associated with obesity, not asthma status;21 GDM rates did not differ between asthma and control groups, within obese or non-obese categories,21 with the odds of GDM 4.2 times higher in obese women and no significant interaction between asthma and obesity.21 However, larger studies, which adjusted for pre-pregnancy maternal obesity, found GDM was associated with maternal asthma,3,6 suggesting that obesity does not account entirely for the increased rate of GDM observed with maternal asthma.

There is evidence indicating metabolic disturbances exist in the asthma population, regardless of weight status. Studies of children with asthma have reported a higher prevalence of insulin resistance,25 and higher likelihood of acanthosis nigricans,26 compared to children without asthma, independent of BMI z-score. These data suggest that metabolic disturbances exist due to the presence of asthma alone. However, these studies did not examine whether asthma management influenced the association. A more recent study found that obese asthmatic children had higher HbA1c levels versus non-asthmatic obese children, suggesting a compounding effect between asthma and obesity upon metabolic markers.27 However, no similar research has been conducted in pregnancy.

Gestational weight gain

Around 50% of women exceed guidelines for gestational weight gain (GWG), with this being more common in overweight and obese women.28 Excess GWG increases the risk for preterm birth, caesarean delivery, LGA infants and macrosomia, and is an independent risk factor for GDM.28,29

A recent IPDMA found that the odds of GDM was increased in women with higher GWG z-scores in the first half of pregnancy, with a 14% increased odds of GDM per standard deviation (SD) increase in GWG z-score (95% CI 1.10–1.18).20 Although greater for overweight and obese women, the risk of GDM was still increased in healthy-weight women with high, versus medium, GWG (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.14–1.58).20 Moreover, a systematic review of interventions targeting GWG demonstrated a decreased risk of GDM.30 These data underline the importance of entering pregnancy at a healthy weight, as well as sustaining healthy weight gain during pregnancy.

The timing of GWG may be more important to GDM risk than the total amount of weight gain. Excess GWG early in pregnancy was predictive of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) in a study of 413 women, independent of total GWG,31 and associated with an increased odds of developing GDM in a study of 2090 singleton pregnancies.32 Rapid and early weight gain likely reflects accumulation of adipose tissue, as opposed to maternal-fetal growth/adaptations, and may result in increased inflammation during pregnancy. Indeed, excess GWG is predominantly comprised of adipose tissue, with no difference in lean mass accrual between women with excess versus adequate GWG.33 Greater visceral, and total, fat accumulation in the first trimester reportedly increases the likelihood of IGT and dysglycaemia in later pregnancy.34,35 Thus, regardless of pre-pregnancy weight status, GWG appears an important factor in GDM development.

There is limited work examining GWG in women with asthma; however, our previous study found 70–79% of women with asthma exceeded recommendations for GWG.23 Another study reported average GWG in women with asthma to be 5.1 kg in trimester one, with a total GWG of 12.5 kg; higher GWG in either trimester one or overall GWG increased the odds of an exacerbation, with a dose-dependent association observed for each kilogram gained in trimester one beyond 5 kg.36 Moreover, trimester one GWG increased the odds for a severe exacerbation.36 Our recent work indicates that the efficacy of biomarker-based asthma management on reducing exacerbations during pregnancy is reduced with excess GWG (IRR 0.58, 95% CI 0.32–1.04).24 Although excess GWG appears prevalent in women with asthma, it is unclear whether women with asthma gain more weight during pregnancy compared to women without asthma. It is also untested whether the trajectory of weight gain in pregnancy differs between women with and without asthma (and contributes to GDM risk).

Adipokines, cytokines and inflammation

During pregnancy, adipocytes and the placenta produce the pro-inflammatory mediators, leptin and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and the anti-inflammatory adiponectin, which may contribute to normal pregnancy alterations. Leptin resistance is common, with leptin concentrations typically two- to threefold higher in pregnancy, peaking at approximately 28 weeks gestation.37,38 Conversely, adiponectin levels progressively decline across gestation.37 Changes in inflammatory mediators during pregnancy relate to functional roles (e.g. hormone regulation, implantation and placental growth, increasing fat store mobilisation); yet, these changes create a shift towards a pro-inflammatory environment and can affect insulin secretion and sensitivity. Thus, pregnancy itself induces a pro-inflammatory state; however, ‘amplification’ of this low-grade inflammatory state is characteristic of GDM, with increased concentrations of inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress markers documented in GDM, versus healthy, pregnancies.37,39

Adipokines may contribute to GDM risk via their role in insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction and adiposity accumulation and distribution, which subsequently affects glucose/insulin metabolism.40 A 2015 meta-analysis of prospective studies found adiponectin levels were lower (weighted mean difference [WMD]: −2.25 [−2.75, −1.75] μg/mL, n = 9 studies), and leptin levels higher (WMD: 7.25 [3.27, 11.22] ng/mL, n = 8 studies), in the first and/or second trimester, in women who subsequently developed GDM versus women who did not.41 However, most of the studies included did not adjust for a measure of body composition or weight status. Furthermore, the findings for other adipokines (e.g. visfatin, resistin, TNFα, vaspin) are less conclusive due to fewer published studies, of which, results are conflicting.41

Research demonstrates associations between adipokine levels in pregnancy and GDM development, regardless of BMI. A 2014 meta-analysis of observational studies38 found leptin levels (WMD 7.14 [4.00, 10.28] ng/mL) and TNFα levels (WMD 2.08 [0.75, 3.41] pg/mL) were elevated in women with, versus without, GDM, when BMI-matched.38 Conversely, adiponectin levels were lower in BMI-matched cases versus controls (WMD −2.66 [−2.85, −2.48] μg/mL).38 This suggests that associations between adipokines and GDM are not entirely attributable to increased BMI, and inferred increased adiposity levels; however, confirmation with accurate measures of adiposity is required.

Asthma is associated with chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, which increases with uncontrolled asthma and exacerbations.42 Alterations in adipokine levels and inflammatory mediators in non-pregnant populations with asthma have been reported, including higher levels of leptin42,43 and interleukin (IL)-6,44 versus controls; and linked to asthma outcomes including lung function,42,44,45 asthma severity42,46 and exacerbations.42,44 Altered adipokine levels have been reported in asthma, independent of BMI, including increased levels of leptin and leptin:adiponectin ratio,42 and decreased ghrelin42 and adiponectin levels.47 Higher leptin and leptin:adiponectin ratio, and lower ghrelin and adiponectin, levels during an exacerbation have also been reported in females.42 Moreover, asthma is associated with oxidative stress, which may inhibit adiponectin gene expression.37 However, whether there is a compounding effect of pregnancy and asthma on adipokine/cytokine alterations and subsequent disturbances in metabolic function, requires examination.

Inadequate adiponectin levels may contribute to GDM development via decreased insulin sensitivity and loss of its anti-inflammatory role. Adiponectin concentrations have been independently associated with insulin resistance, weight and serum lipids in pregnancy, and it has been suggested that depressed adiponectin levels contribute to macrosomia associated with GDM pregnancies.40 Conversely, higher leptin and TNFα levels propagate inflammation and may raise insulin resistance,41 with both demonstrated to suppress β-cell insulin secretion.40 Furthermore, insulin signalling in insulin-sensitive tissues is impaired by TNFα,40 with increases in TNFα across pregnancy independently associated with adverse changes in insulin sensitivity.40 Notably, TNFα and IL-6 downregulate the adiponectin gene and can suppress adipocyte transcription of adiponectin.37

Levels of adiponectin and leptin decrease and increase, respectively, as pregnancy progresses. Early GWG may reflect increases in adipose tissue33 and subsequent amplification of adverse alterations in adipokines, creating a pro-inflammatory shift early in pregnancy. There is the potential risk for more dramatic disturbances in adipokine levels in the pregnant woman with asthma, whose levels are already altered due to the presence of asthma, thus, predisposing them to GDM development. However, no studies have investigated whether adipokine levels are altered in women with asthma during pregnancy, with and without GDM.

Vitamin D and pregnancy

During pregnancy, physiological changes in the metabolism of various nutrients occur, including vitamin D, which has been associated with several pregnancy-related outcomes, including GDM.48–50 The active form of vitamin D, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)D), increases from early gestation, peaking in the third trimester, with levels two to three times higher than non-pregnant women; yet, serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), the most common measure of vitamin D status, are relatively unaffected.51 Despite this, suboptimal vitamin D status has been highlighted as a common nutritional problem during pregnancy, regardless of latitude or sun exposure,52 and it is unclear what therapeutic target is required for optimal perinatal health.

A 2018 meta-analysis of observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) free of the Hawthorne effect, found low versus high, 25(OH)D levels in pregnancy were associated with an 85% increased odds of developing GDM (95% CI 1.47–2.33, n = 38 studies, n = 29,902 pregnancies).53 25(OH)D levels were also inversely associated with fasting plasma glucose and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) but not fasting insulin or HbA1c.53 However, vitamin D supplementation was not protective against GDM (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.39–1.31, n = 4 studies, n = 968 pregnancies);53 yet, this result became statistically significant with the omission of one study, suggesting it heavily weighted the result. Indeed, the population in the omitted trial was extremely vitamin D deficient, and received the intervention for only four weeks prior to GDM screening.54 Furthermore, only one of the trials included in the meta-analysis was powered to detect a difference in GDM incidence, which it did.55 Thus, due to heterogeneity in the available evidence, it remains unclear whether vitamin D supplementation plays a role in GDM prevention.

Circulating 25(OH)D levels are reportedly lower in the asthmatic population.56–58 We previously reported persistent vitamin D insufficiency (25(OH)D < 75 nmol/L) in 60% of women with asthma during pregnancy, which was associated with poorer infant respiratory outcomes.59 However, whether vitamin D status impacts the association between maternal asthma and GDM risk is yet to be examined.

Vitamin D has varied extra-skeletal roles, notably in the regulation of insulin production, improvements in insulin signalling and sensitivity, and postulated interactions with insulin-like growth factor to impact glucose homeostasis.51,60 Vitamin D can act directly on β-cell function to increase insulin secretion:9 observational studies report a link between low 25(OH)D levels and the development of insulin resistance, and most RCTs report improvements in insulin sensitivity with supplementation.60 Vitamin D can reduce systemic inflammation associated with insulin resistance,9 and reportedly inhibits adipose tissue, and immune cell, inflammation.61 It may also play a protective role against glucolipotoxicity, with one in vitro study supporting 1,25(OH)D in the regulation of key enzymes involved in protective pathways.62

Given these findings, and the documented low 25(OH)D levels during pregnancy, it is plausible that the increased prevalence of GDM in asthma is mediated via lower 25(OH)D levels, reducing insulin secretion and, consequently, increasing blood glucose levels.

Asthma management: Medications, severity and control

A 2014 meta-analysis of cohort studies examining adverse perinatal outcomes with maternal asthma, showed that asthma in pregnancy was associated with a 45% increased risk of GDM where no active management was given to study participants (95% CI 1.20–1.76, n = 12 studies), compared to women without asthma.4 In contrast, among seven studies where active asthma management was described, there was no significant association between maternal asthma and GDM (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.81–1.46), whilst bronchodilator use was associated with a reduced risk (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.57–0.72, n = 2 studies).4 This suggests that asthma management influences metabolic disturbance, via direct medication effects and/or indirect effects on asthma control and/or severity during pregnancy.

Two subsequent nested case–control studies examined the effect of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) on GDM risk. The first examined data from 1001 pregnant women with asthma and GDM, versus 30,030 matched women with asthma without GDM, from Quebec.63 The ICS (+/− long-acting β-agonist [LABA]) dosage was not associated with GDM risk; however, authors concluded that further studies are needed that adjust for obesity and asthma severity.63 The second study, including women with or without asthma, compared data from 34,190 GDM cases with 170,934 matched women without GDM, from Korea.64 Authors adjusted for GDM-associated comorbidities including history of GDM, pregnancy-induced hypertension and impaired glucose metabolism, and concomitant respiratory medication use.64 There was no significant association between ICS use, with or without LABA, in the 180 days preceding GDM diagnosis, and GDM risk.64 An ICS medication possession rate of 0–0.3 versus 0, was associated with a 20% lower odds of GDM after adjustment for concomitant respiratory medication use, age, comorbidities and healthcare utilisation during pregnancy;64 yet, further adjustment for medication use pre-pregnancy removed significance.64 Thus, limited evidence to date suggests that ICS use is not associated with GDM risk, which may be attributable to a lack of biological effect of ICS on glucose control during pregnancy.65

In line with the hypothesis that GDM may be driven by inflammatory pathways, one may infer that the use of anti-inflammatory medications may reduce the risk of GDM; yet, studies in non-pregnant populations have found that high-dose ICS use is associated with a greater risk of diabetes onset.66 Therefore, the pathogenesis in pregnancy may be different to the non-pregnant state, and requires further investigation.

Conversely, oral corticosteroids (OCSs) contribute to insulin resistance and subsequent glucose intolerance and Type 2 diabetes.67 Given the shared risk factors and pathogenesis, OCS use may increase GDM risk.64 OCSs are commonly used to manage severe uncontrolled asthma and acute exacerbations of asthma,68 and, in women who receive them preceding or during pregnancy, could potentially impact glucose control and GDM risk. However, no studies have examined asthma-related OCS use and GDM risk, with insufficient evidence in other diseases to support a link between OCS exposure and GDM development.69

Multiple asthma medication use during pregnancy has also been associated with increased GDM rates.70 Notably, overweight and obesity increased the odds of asthma medication use in early and late pregnancy, compared to a healthy weight;70 however, medication use, including polypharmacy, may be a proxy marker of asthma control or severity, regardless of weight status. A 2014 meta-analysis found moderate to severe asthma increased the risk of GDM (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.06–1.33, n = 3 studies), yet, exacerbations did not (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.82–4.95, n = 2 studies).4 Conversely, a 2014 Quebec study examining 12,975 asthmatic, and 27,989 non-asthmatic, pregnancies, found asthma severity and control in the year preceding 20 weeks gestation were unrelated to GDM risk.5 Likewise, a study of 938 women found no association between exacerbations, or asthma severity, and GDM risk.6 Conflicting and limited evidence underlines the need for further research examining the influence of asthma medications, control and severity, on GDM risk.

Conclusion

The increased risk of GDM with asthma appears to be mitigated by active asthma management during pregnancy. Clinical trials exploring antenatal asthma management as a strategy to improve maternal–fetal outcomes by reducing the risk imposed by asthma and GDM, and establishing the underlying mechanism linking these conditions, could uncover new treatment options. Furthermore, multiple risk factors are common to both asthma and GDM, notably obesity, excess GWG, altered levels of adipokines and systemic inflammation and insufficient vitamin D levels; understanding and addressing these factors, if beneficial, in antenatal care, may reduce the risk of GDM in women with asthma and lead to improved outcomes for mother and child.

Examination of factors unique to women with asthma, which increase GDM risk, is needed, thereby enabling potential intervention strategies to be investigated which aim to reduce the incidence of GDM in this high-risk group. Given the high prevalence and individual impact of maternal asthma and GDM on maternal and offspring health, whether the presence of both conditions compounds the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, requires investigation.

Acknowledgements

None

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PGG reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: MEJ is supported by the Hunter Children’s Research Foundation Peggy Lang Early Career Fellowship. HLB is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (APP1120070) and the Mater Foundation. PGG received a Practitioner Fellowship from the NHMRC (APP1155810). VEM was the recipient of a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1084816) and is currently the Gladys M Brawn Memorial Career Development Fellow at the University of Newcastle.

Ethical approval: Not applicable

Informed consent: Not applicable

Guarantor: Dr Jensen guarantees the manuscripts accuracy and the contribution of all co-authors.

Author contribution: MEJ researched the literature, conceived the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

ORCID iD: ME Jensen https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8653-4801

References

- 1.Murphy VE, Jensen ME, Gibson PG. Asthma during pregnancy: Exacerbations, management, and health outcomes for mother and infant. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 38: 160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Incidence of gestational diabetes in Australia. Cat. no. CVD 85, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/incidence-of-gestational-diabetes-in-australia (2019, accessed 01 November 2019).

- 3.Mendola P, Laughon SK, Mannisto TI, et al. Obstetric complications among US women with asthma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 208: 127 e121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G, Murphy VE, Namazy J, et al. The risk of maternal and placental complications in pregnant women with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014; 27: 934–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blais L, Kettani FZ, Forget A. Associations of maternal asthma severity and control with pregnancy complications. J Asthma 2014; 51: 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali Z, Nilas L, Ulrik CS. Low risk of adverse obstetrical and perinatal outcome in pregnancies complicated by asthma: a case control study. Respir Med 2016; 120: 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy VE, Namazy JA, Powell H, et al. A meta-analysis of adverse perinatal outcomes in women with asthma. Bjog 2011; 118: 1314–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johns EC, Denison FC, Norman JE, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: mechanisms, treatment, and complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018; 29: 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kampmann U, Madsen LR, Skajaa GO, et al. Gestational diabetes: a clinical update. World J Diabet 2015; 6: 1065–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billionnet C, Mitanchez D, Weill A, et al. Gestational diabetes and adverse perinatal outcomes from 716,152 births in France in 2012. Diabetologia 2017; 60: 636–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morten M, Collison A, Murphy VE, et al. Managing asthma in pregnancy (MAP) trial: FENO levels and childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142: 1765–1772.e1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattes J, Murphy VE, Powell H, et al. Prenatal origins of bronchiolitis: protective effect of optimised asthma management during pregnancy. Thorax 2014; 69: 383–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armengaud JB, Ma RCW, Siddeek B, et al. Offspring of mothers with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy: the short term and long-term impact. What is new?. Diabet Res Clin Pract 2018; 145: 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sifnaios E, Mastorakos G, Psarra K, et al. Gestational diabetes and T-cell (Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg) immune profile. In Vivo 2019; 33: 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-Arango LF, Barrett HL, McIntyre HD, et al. Connections between the gut microbiome and metabolic hormones in early pregnancy in overweight and obese women. Diabetes 2016; 65: 2214–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poston L, Caleyachetty R, Cnattingius S, et al. Preconceptional and maternal obesity: epidemiology and health consequences. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2016; 4: 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thrift AP, Callaway LK. The effect of obesity on pregnancy outcomes among Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous women. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godfrey KM, Reynolds RM, Prescott SL, et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2017; 5: 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet Care 2007; 30: 2070–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos S, Voerman E, Amiano P, et al. Impact of maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy complications: an individual participant data meta-analysis of European, North American, and Australian cohorts. Bjog 2019; 126: 984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendler I, Schatz M, Momirova V, et al. Association of obesity with pulmonary and nonpulmonary complications of pregnancy in asthmatic women. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tata LJ, Lewis SA, McKeever TM, et al. A comprehensive analysis of adverse obstetric and pediatric complications in women with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 991–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy VE, Jensen ME, Powell H, et al. Influence of maternal body mass index and macrophage activation on asthma exacerbations in pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5: 981–987.e981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy VE, Jensen ME, Robijn AL, et al. How maternal BMI modifies the impact of personalised asthma management in pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 07: 13. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arshi M, Cardinal J, Hill RJ, et al. Asthma and insulin resistance in children. Respirology 2010; 15: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cottrell L, Neal WA, Ice C, et al. Metabolic abnormalities in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perdue AD, Cottrell LA, Lilly CL, et al. Pediatric metabolic outcome comparisons based on a spectrum of obesity and asthmatic symptoms. J Asthma 2019; 56: 388--394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilmore LA, Klempel-Donchenko M, Redman LM. Pregnancy as a window to future health: excessive gestational weight gain and obesity. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39: 296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kominiarek MA, Peaceman AM. Gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 217: 642–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett CJ, Walker RE, Blumfield ML, et al. Interventions designed to reduce excessive gestational weight gain can reduce the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Diabet Res Clin Pract 2018; 141: 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomedi LE, Simhan HN, Chang CC, et al. Gestational weight gain, early pregnancy maternal adiposity distribution, and maternal hyperglycemia. Matern Child Health J 2014; 18: 1265–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong C, Li X, Chen R, et al. Greater early and mid-pregnancy gestational weight gain are associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2017; 22: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berggren EK, Groh-Wargo S, Presley L, et al. Maternal fat, but not lean, mass is increased among overweight/obese women with excess gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 214: 745–e741.745.e745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin AM, Berger H, Nisenbaum R, et al. Abdominal visceral adiposity in the first trimester predicts glucose intolerance in later pregnancy. Diabet Care 2009; 32: 1308–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Souza LR, Berger H, Retnakaran R, et al. First-trimester maternal abdominal adiposity predicts dysglycemia and gestational diabetes mellitus in midpregnancy. Diabet Care 2016; 39: 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali Z, Nilas L, Ulrik CS. Excessive gestational weight gain in first trimester is a risk factor for exacerbation of asthma during pregnancy: a prospective study of 1283 pregnancies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 761--767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miehle K, Stepan H, Fasshauer M. Leptin, adiponectin and other adipokines in gestational diabetes mellitus and pre-eclampsia. Clin Endocrinol 2012; 76: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu J, Zhao YH, Chen YP, et al. Maternal circulating concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, leptin, and adiponectin in gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014: 926932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shang M, Dong X, Hou L. Correlation of adipokines and markers of oxidative stress in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and their newborns. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2018; 44: 637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fasshauer M, Bluher M, Stumvoll M. Adipokines in gestational diabetes. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2014; 2: 488–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao W, Baecker A, Song Y, et al. Adipokine levels during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Metab Clin Exp 2015; 64: 756–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsaroucha A, Daniil Z, Malli F, et al. Leptin, adiponectin, and ghrelin levels in female patients with asthma during stable and exacerbation periods. J Asthma 2013; 50: 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sood A, Ford ES, Camargo CA., Jr., Association between leptin and asthma in adults. Thorax 2006; 61: 300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters MC, McGrath KW, Hawkins GA, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 concentrations, metabolic dysfunction, and asthma severity: a cross-sectional analysis of two cohorts. Lancet Respirat Med 2016; 4: 574–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hickson DA, Burchfiel CM, Petrini MFet al. Leptin is inversely associated with lung function in African Americans, independent of adiposity: the Jackson Heart Study. Obesity 2011; 19: 1054–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nasiri Kalmarzi R, Ataee P, Mansori M, et al. Serum levels of adiponectin and leptin in asthmatic patients and its relation with asthma severity, lung function and BMI. Allergol Immunopathol 2017; 45: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sood A, Cui X, Qualls C, et al. Association between asthma and serum adiponectin concentration in women. Thorax 2008; 63: 877–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poel YH, Hummel P, Lips P, et al. Vitamin D and gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Inter Med 2012; 23: 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purswani JM, Gala P, Dwarkanath P, et al. The role of vitamin D in pre-eclampsia: a systematic review. BMC Preg Childbirth 2017; 17: 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei SQ, Qi HP, Luo ZC, et al. Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013; 26: 889–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Websky K, Hasan AA, Reichetzeder C, et al. Impact of vitamin D on pregnancy-related disorders and on offspring outcome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018; 180: 51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saraf R, Morton SM, Camargo CA, Jr., et al. Global summary of maternal and newborn vitamin D status—a systematic review. Mater Child Nutrit 2015; 12: 647–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Gong Y, Xue H, et al. Vitamin D and gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review based on data free of Hawthorne effect. Bjog 2018; 125: 784–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hossain N, Kanani FH, Ramzan S, et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of maternal vitamin D supplementation: results of an open-label, randomized controlled trial of antenatal vitamin D supplementation in Pakistani women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 2448–2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mojibian M, Soheilykhah S, Fallah Zadeh MA, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on maternal and neonatal outcome: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Reprod Med 2015; 13: 687–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shahin MYA, El-Lawah AA, Amin A, et al. Study of serum vitamin D level in adult patients with bronchial asthma. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc 2017; 66: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niruban SJ, Alagiakrishnan K, Beach J, et al. Association between vitamin D and respiratory outcomes in Canadian adolescents and adults. J Asthma 2015; 52: 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamašauskienė L, Gasiūnienė E, Lavinskienė S, et al. Evaluation of vitamin D levels in allergic and non-allergic asthma. Medicina 2015; 51: 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jensen ME, Murphy VE, Gibson PG, et al. Vitamin D status in pregnant women with asthma and its association with adverse respiratory outcomes during infancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019; 32: 1820–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szymczak-Pajor I, Sliwinska A. Analysis of association between vitamin D deficiency and insulin resistance. Nutrients 2019; 11: 794--821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garbossa SG, Folli F. Vitamin D, sub-inflammation and insulin resistance. A window on a potential role for the interaction between bone and glucose metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017; 18: 243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuricova K, Pleskacova A, Pacal L, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D increases the gene expression of enzymes protecting from glucolipotoxicity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and human primary endothelial cells. Food Funct 2016; 7: 2537–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baribeau V, Beauchesne MF, Rey E, et al. The use of asthma controller medications during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138: 1732–1733.e1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee CH, Kim J, Jang EJ, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids use is not associated with an increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus: two nested case-control studies. Medicine 2016; 95: e3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borsi SH, Rashidi H, Shaabanpour M, et al. The effects of inhaled corticosteroid on insulin sensitivity in asthmatic patients. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2018; 88: 892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suissa S, Kezouh A, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids and the risks of diabetes onset and progression. Am J Med 2010; 123: 1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tamez-Perez HE, Quintanilla-Flores DL, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Steroid hyperglycemia: prevalence, early detection and therapeutic recommendations: a narrative review. World J Diabet 2015; 6: 1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention, 2019: Available from: www.ginasthma.org.

- 69.Bandoli G, Palmsten K, Forbess Smith CJ, et al. A review of systemic corticosteroid use in pregnancy and the risk of select pregnancy and birth outcomes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2017; 43: 489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kallen B, Otterblad Olausson P. Use of anti-asthmatic drugs during pregnancy. 1. Maternal characteristics, pregnancy and delivery complications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]