There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Allosteric inhibition of Hif-2α normalized the erythropoietin and endothelin-1 levels in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice.

Oral delivery of an Hif-2α inhibitor reversed polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in genetically defined murine models of human diseases.

Abstract

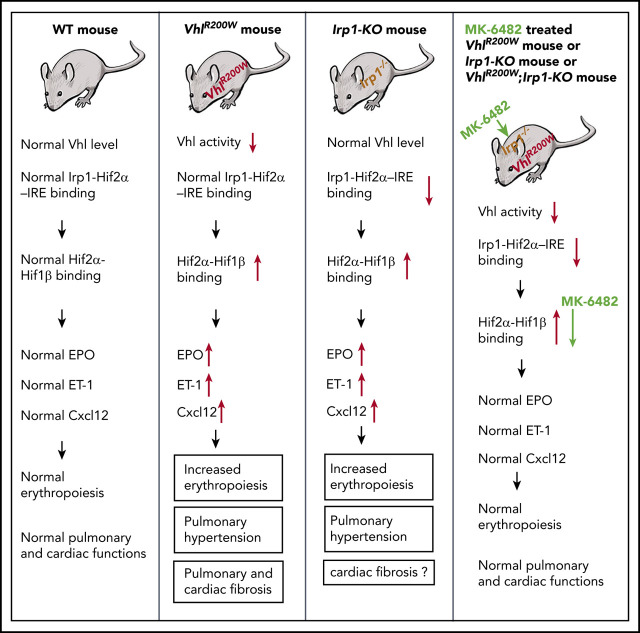

Polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension are 2 human diseases for which better therapies are needed. Upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) and its target genes, erythropoietin (EPO) and endothelin-1, causes polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in patients with Chuvash polycythemia who are homozygous for the R200W mutation in the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene and in a murine mouse model of Chuvash polycythemia that bears the same homozygous VhlR200W mutation. Moreover, the aged VhlR200W mice developed pulmonary fibrosis, most likely due to the increased expression of Cxcl-12, another Hif-2α target. Patients with mutations in iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) also develop polycythemia, and Irp1-knockout (Irp1-KO) mice exhibit polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac fibrosis attributable to translational derepression of Hif-2α, and the resultant high expression of the Hif-2α targets EPO, endothelin-1, and Cxcl-12. In this study, we inactivated Hif-2α with the second-generation allosteric HIF-2α inhibitor MK-6482 in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. MK-6482 treatment decreased EPO production and reversed polycythemia in all 3 mouse models. Drug treatment also decreased right ventricular pressure and mitigated pulmonary hypertension in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice to near normal wild-type levels and normalized the movement of the cardiac interventricular septum in VhlR200Wmice. MK-6482 treatment reduced the increased expression of Cxcl-12, which, in association with CXCR4, mediates fibrocyte influx into the lungs, potentially causing pulmonary fibrosis. Our results suggest that oral intake of MK-6482 could represent a new approach to treatment of patients with polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis, and complications caused by elevated expression of HIF-2α.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Polycythemia, also known as erythrocytosis, can result from multiple causes, including mutations in proteins involved in oxygen sensing and erythropoiesis, such as in the erythropoietin-erythropoietin receptor (EPO-EPOR), and mutations in hemoglobins (HBB, HBA), 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase (BPGM), VHL, EGLN1 (prolyl hydroxylase domain-2 [PHD-2]), endothelial PAS-domain containing protein-1 (EPAS1, HIF-2α) and IRP1 genes that increase HIF-2α expression levels in renal tissues or endothelia.1-9 Pulmonary hypertension can develop as a primary disease in which mutations in several disease genes have been identified,10 including bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2)11 and VHL in Chuvash polycythemia,12,13 but in many cases, the causes and pathophysiology are not well understood. Better therapies are needed for polycythemia14 and pulmonary hypertension.15,16

A homozygous germline loss-of-function mutation in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene at codon 200 (R200W) is associated with a disease commonly known as Chuvash polycythemia, an inherited disease that is endemic in, but not limited to, the Chuvash region of Russia.6,17,18 In addition to polycythemia, these patients develop pulmonary hypertension, thromboses, and cerebral hemorrhages and die prematurely.18 A mouse model bearing the same prevalent homozygous VhlR200W mutation recapitulates the polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension phenotypes,13,19 and older VhlR200W mice also exhibit pulmonary fibrosis.13

The VHL protein, which plays a crucial role in cellular oxygen sensing and regulation of α subunits of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-α), is a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that mediates proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α, also known as EPAS-1, after oxygen-dependent hydroxylation by prolyl-hydroxylases (PHDs), predominantly PHD-2, in normal oxygen conditions.20-24 HIF-1α and HIF-2α are transcription factors that are involved in mediating the physiological response to changes in oxygen concentrations. At low cellular oxygen (hypoxic) conditions, impaired hydroxylation of HIF-α by PHDs prevents the VHL ubiquitin ligase complex from ligating and degrading HIF-α.23 Stabilized HIF-1α and HIF-2α translocate into the nucleus where they dimerize with the constitutively expressed aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), also known as HIF-1β, to form an active transcription factor complex.25 HIF-α-ARNT complexes bind to hypoxia responsive elements26 and activate transcription of numerous genes, including EPO, endothelin-1, and C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL-12).21,27,28 Loss of VHL function leads to accumulation of HIF-α and high expression of the HIF target genes, highlighting the importance of VHL in oxygen sensing and cardiovascular homeostasis. Although both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are crucial regulators for the response to hypoxia, results of previous studies have demonstrated that HIF-2α activation has a predominant role in the pathogenesis of several polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension models.13,29-31 In patients with Chuvash polycythemia and the VHLR200W mouse model, impaired degradation of HIF-2α is responsible for both polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension,12,13,32 as heterozygous deletion of Hif-2α, but not of Hif-1α, prevented the polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in mice with the VhlR200W mutation.13 In addition, aged VhlR200W mice exhibited pulmonary fibrosis.13 Taken together, the results of these studies demonstrate that the PHD2/VHL/HIF-2α axis is important in regulating Chuvash polycythemia, pulmonary vascular homeostasis, and pulmonary fibrosis. Overexpression of HIF-2α led to elevated levels of several of its targets, including EPO, which promotes the production of red blood cells (RBCs); endothelin-1, which is a potent vasoconstrictor in endothelial cells33,34; and Cxcl-12 which promotes fibrosis in lungs of VhlR200W mice.13

Recently, multiple patients with polycythemia phenotypes similar to patients with Chuvash polycythemia but without VHLR200W mutations were found to carry mutations in iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) in Icelandic pedigrees.3 IRP1 and IRP2 are homologous mammalian cytosolic proteins that maintain cellular iron homeostasis by binding to a RNA stem-loop secondary structure, known as iron responsive elements (IREs) located in the 5′ or 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs), encoding proteins that are involved in iron import, utilization, storage, and export.35-37 Binding of the IRPs to the HIF-2α-IRE at 5′ UTR represses translation of HIF-2α.38,39 We have previously studied mice with targeted deletion of Irp140 and have shown that these mice also develop polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension.4 Moreover, cardiac fibrosis and cardiomyocyte degeneration were observed in older Irp1-KO mice (>12 months old) maintained on a low-iron diet.4 The polycythemia phenotype of Irp1-KO mice was also reported independently by 2 other research groups.9,41 Deletion of Irp1 leads to increased translation of Hif-2α, resulting in elevated levels of EPO in serum and endothelin-1 in pulmonary endothelia.4 Thus, a major molecular cause of polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in patients and mouse models with VHLR200W and IRP1 mutations is excess HIF-2α expression in multiple tissues due to either its decreased degradation or increased synthesis. HIF-2α also regulates expression of the CXCL-12 chemokine,27 and increased expression of Cxcl-12 has been observed in the lungs of VhlR200W13 and Irp1-KO mice.4 CXCL-12 plays an important role in the progression of pulmonary hypertension42 and in association with C-X-C motif chemokine receptor-4 (CXCR-4) promotes fibrocyte influx into the lungs, leading to fibroblast proliferation and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.43-46

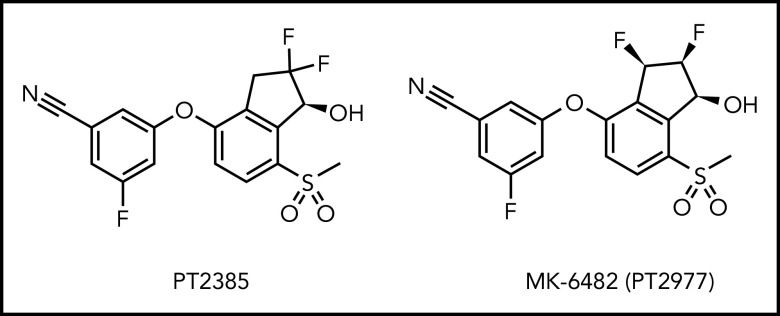

Structural analysis of HIF-2α has identified a large ligand-binding pocket in its PAS-B domain47-49 that is absent in HIF-1α.50 Peloton Therapeutics Inc (Dallas, TX) and Merck & Co Inc (Kenilworth, NJ) have developed several small-molecule drugs, including PT2385 and MK-6482, also known as PT2977 (molecular structures shown in Figure 1), which can specifically occupy this cavity in the PAS-B domain of HIF-2α51-53 and can thereby disrupt the binding of HIF-2α to its heterodimerization partner Hif-1β, and inhibit HIF-2α–mediated transcriptional activity. These small molecules inhibit the expression of HIF-2α target genes, including EPO, endothelin-1, and CXCL-12. The second-generation drug MK-6482 (3-[(1S,2S,3R)-2,3-difluoro-1-hydroxy-7-methylsulfonylindan-4-yl]oxy-5-fluorobenzonitrile)53,54 contains a vicinal difluoro group that replaces the geminal difluoro group in the first-generation HIF-2α inhibitor PT2385, and these chemical modifications have been found to improve the pharmacokinetic profile and increase the potency of the modified drug.53 Since VEGFA is a target of HIF-2α, and it plays a pathogenic role in advanced renal cell carcinoma, MK-6482 has been used in clinical trials to treat renal cell carcinoma, and has shown encouraging antitumor activity, together with a favorable safety profile.53-56 In this study we treated VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice with MK-6482, hypothesizing that by inhibiting the Hif-2α activity, this drug would attenuate polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary fibrosis in these mice. Our results showed that oral MK-6482 treatment successfully reversed both polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in all 3 mouse models and normalized the expression of Cxcl-12, a marker for pulmonary fibrosis, in VhlR200W mice, indicating promising potential of this HIF-2α inhibitor for treatment of these harmful human diseases.

Figure 1.

Structures of PT2385 and MK-6482 (also known as PT2977), specific inhibitors of HIF-2α. Structure of the originally designed HIF-2α inhibitor PT2385, which contains the difluoro group in the geminal position, was modified to enhance the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of MK-6482 in which the difluoro group is in the vicinal position.53

Materials and methods

Study approval

All procedures involving mice were performed according to protocols approved by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 18-038) and met National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for humane care of animals.

Animals

The VhlR200W mice were originally generated by Hickey et al.19 Heterozygous breeding pairs (C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Mary Slingo and Peter Robbins57 (University of Oxford). The mice were genotyped as described by Hickey et al.19 Irp1-KO mice were generated as described40 and backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for 10 generations. VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice were made by first crossing VhlR200W mice with Irp1-KO mice and breeding the resultant heterozygous mice. All the experiments were conducted in 6- to 11-month-old mice, unless specifically mentioned. The mice were weaned at 3 to 4 weeks of age and were maintained on a normal NIH-07 diet, unless otherwise mentioned.

Drug treatment

We received pharmaceutical grade MK-6482 from Peloton Therapeutics Inc and Merck & Co, Inc. MK-6482 was formulated with 10% absolute ethanol, 30% PEG400, 60% water containing 0.5% methylcellulose, and 0.5% Tween 80 (all pharmaceutical grade from Spectrum Chemicals), according to methods used by other investigators.52 The dose was 0.1 mg/g per day. Wild-type (WT), VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice were treated via oral gavage once daily. Control mice received only vehicle. After 5 weeks, we measured complete blood count (CBC) and intraventricular pressure by Millar catheterization, harvested serum, euthanized the mice, and harvested tissues.

Low iron diet description

We placed the Irp1-KO mice for our main experiment on low-iron diets 2 weeks before the start of drug treatment to maximize their polycythemia phenotype.4 The low-iron diet was bought from Harlan Teklad and contained 3.7 ± 0.9 mg iron/kg chow (measured by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry).

Hep3b cells

The Hep3b human cell line was cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1% nonessential amino acids at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were harvested after growing at either 21% O2 or 2.5% O2 in the presence or absence of 20 μM MK-6482 for 16 hours.

Hematocrit measurement: capillary spin method

We withdrew ∼100 μL of blood from each mouse by using the mandibular bleeding method and funneling into a heparin-coated tube. Hematocrit tubes were ∼80% filled with blood by capillary action and sealed. We centrifuged the sealed tubes in an LW Scientific microhematocrit centrifuge and used a hematocrit reader to measure hematocrit.

CBC measurement

Approximately 100 μL of blood was harvested into a heparin-coated tube from each mouse via mandibular bleeds. All the CBC measurements were performed with an IDEXX ProCyte Dx Hematology Analyzer.

Plasma volume calculation

Plasma volume was calculated from the known weight of the mice and the centrifuged hematocrit data according to the equation: plasma volume (ml) = total blood volume (ml) × (1 − hematocrit/100). Total blood volume was calculated as 0.079 mL/g × weight of mouse in grams, assuming that a mouse has, on average, 79 mL/kg of body weight blood. In this calculation of plasma volume, we used data obtained only from the mice with comparable body weights to minimize the relative error arising from total blood volume calculation.

Serum EPO, endothelin-1, and Cxcl-12 measurements by ELISA

EPO, endothelin-1, and Cxcl-12 were measured in serum samples with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from R&D Systems, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed with primer sequences for EPO, endothelin-1, Cxcl-12, and actin, according to published methods.4,58 The results were normalized against actin levels.

Intracardial pressure measurements

We invasively measured the intraventricular pressure by using a microtip pressure transducer catheter connected to an electrostatic chart recorder (Millar Instruments). After the mice were anesthetized with 1% to 3% isoflurane, the right external jugular veins were cannulated. The catheter was then advanced into the right ventricle. Correct placement was verified according to the right ventricular pressure curve, and the pressure and volume tracings were then recorded. The body temperature of the mice was maintained at 37°C to 38°C. The data were recorded using LabChart software (AD Instruments). The mice were then euthanized, while under anesthesia, by cervical dislocation or by exsanguination.

Hif-2α western blot analysis

Kidney tissue lysates were prepared, and western blot analysis of Hif-2α was performed as previously described59 with an Hif-2α antibody (catalog no. NB100-122; Novus Biologicals).

Echocardiography

We performed transthoracic echocardiography in mice with a high-frequency ultrasound system (Vevo 2100; VisualSonics). We acquired the images with an MS-400 transducer (VisualSonics) with a center operating frequency of 30 MHz, and a broadband frequency of 18 to 38 MHz. The axial resolution and footprint of this MS-400 transducer are 50 µm and 20 × 5 mm, respectively. Two-dimensional images were obtained for multiple views of the heart.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses for multiple comparisons were performed with an ordinary 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

MK-6482 attenuated polycythemia in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice

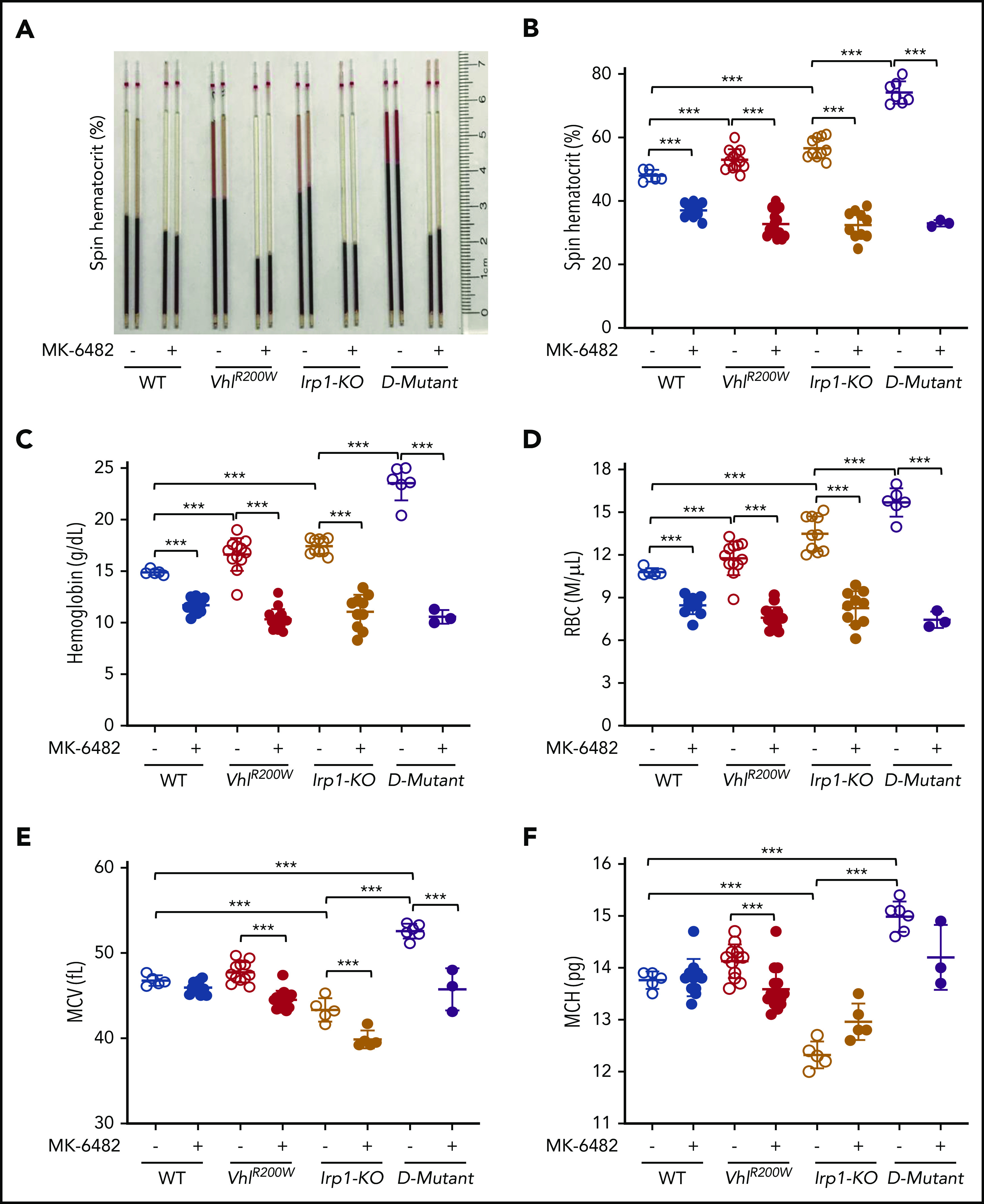

We placed the Irp1-KO mice on a low-iron diet 2 weeks before drug treatment to enhance polycythemia.4 We measured hematocrit levels of untreated, vehicle-treated, and MK-6482 (Figure 1)–treated WT, VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice by capillary centrifugation. There was no significant difference in hematocrit levels between the untreated and vehicle-only–treated mice (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). The hematocrit levels of vehicle-treated VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice were significantly higher than those of vehicle-treated WT mice (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 2A), reconfirming that these mutant mice had polycythemia.4,19 The hematocrits of vehicle-treated double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice were substantially more elevated than those of either the Irp1-KO or the VhlR200W mice (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 2A), as previously observed, consistent with their independent mechanisms of elevating HIF-2α, which should be additive.58 After drug (MK-6482) treatment, the hematocrits of the VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice decreased dramatically (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 2A). No placebo effect was observed also for the other CBC parameters (supplemental Figure 1A-D). The analyses showed increased hemoglobin and RBC levels in vehicle-treated VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice compared with the WT animals (Figure 2C-D). MK-6482 treatment markedly diminished levels of hemoglobin and RBC counts of the mutant and double-mutant mice, showing complete recovery from polycythemia in all 3 mouse models. We treated 5 Irp1-KO mice with MK-6482 and 5 Irp1-KO mice with vehicle, without maintaining them on a low-iron diet, and found that the effect of the drug on the hematocrits of those mice was comparable with that observed with the Irp1-KO mice receiving the low-iron diet (supplemental Figure 3). Plasma volumes, calculated from the weight of the mice and the centrifuged (spin) hematocrit data, were reduced in the VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice, compared with that in the WT mice (supplemental Figure 2B). During drug treatment, calculated plasma volumes were increased in all the mutant and double-mutant mice, indicating that the observed changes in hemoglobin levels were complemented with the changes in plasma volumes.18,60 MCV and MCH levels in Irp1-KO mice, but not in VhlR200W mice, were lower than those in WT mice (Figure 2E-F), consistent with previously observed systemic iron deficiency in Irp1-KO mice.4 Drug treatment did not restore normal MCV and MCH levels in the Irp1-KO mice. The MCHC levels of VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice increased on treatment with the drug (supplemental Figure 2C). Significantly increased reticulocytosis in Irp1-KO mice, as compared with the WT controls (supplemental Figure 2D), indicated that there was stress erythropoiesis in the mice.8 However, reticulocytosis was diminished when the Irp1-KO mice were treated with MK-6482, suggesting that the drug mitigated stress erythropoiesis in these mice. We did not find any significant effect of either the mutations or the drug on WBC and platelet counts, although a slight increase in platelet levels was observed with drug treatment in all 3 mouse models (supplemental Figure 2E-F).

Figure 2.

MK-6482 reversed polycythemia in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. Hematocrit levels, as determined by the capillary centrifugation method (A-B), hemoglobin (C), RBC (D), MCV (E), and MCH (F) levels of 6- to 11-month-old WT, VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice treated with vehicle or the Hif-2α inhibitor MK-6482. Oral administration of MK-6482 significantly decreased the elevated hematocrit, hemoglobin, and RBC levels, and ameliorated polycythemia in all 3 mutant models. MK-6482 also decreased MCV and MCH values in the mutant mice. Notably, MCV and MCH levels were decreased in the Irp1-KO mice, suggesting that IRP1 deficiency induces mild iron deficiency that is reversed by VhlR200W mutation. ***P < .001, by ordinary 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons). D-mutant, double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mouse.

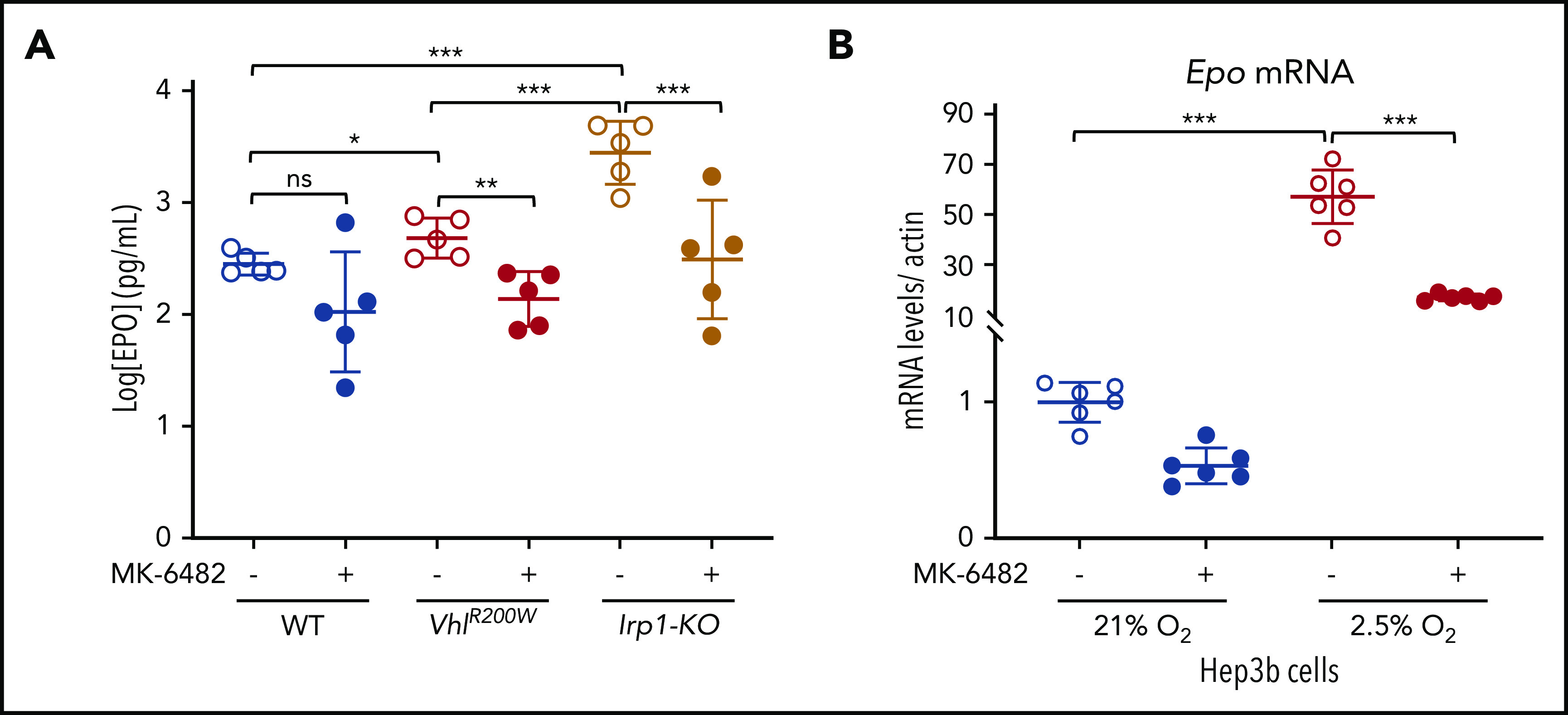

MK-6482 attenuated polycythemia in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice by reducing the expression of EPO

EPO is a glycoprotein cytokine secreted by the kidneys in response to hypoxia. It is a specific transcriptional target of HIF-2α, but not of HIF-1α.61 Because EPO stimulates RBC production, we measured EPO levels in the serum of vehicle- and drug-treated mice by ELISA, and we observed that the elevated EPO levels of VhlR200W mice and Irp1-KO mice were significantly diminished during drug treatment (Figure 3A). Notably, Irp1-KO mice had more than fivefold higher EPO levels than VhlR200W mice. MK-6482 treatment also significantly decreased the expression of EPO in Hep3b cells when the cells were grown at low (2.5%) oxygen concentrations (Figure 3B), to elicit expression of HIF-2α in response to hypoxia. These results demonstrated that MK-6482 attenuates polycythemia by reducing the EPO level in the mutant mice, and the drug also decreases the expression of EPO, in response to cellular hypoxia. We assessed Hif-2α protein levels in the kidney lysates of the vehicle- or drug-treated VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice, as EPO is a specific target of HIF-2α.61 Hif-2α protein levels were not affected by drug treatment (supplemental Figure 4), as expected, because MK-6482 inhibits only HIF-2α–mediated transcriptional activity by disturbing HIF-2α-Hif-1β binding and does not contribute to the degradation of HIF-2α protein.53

Figure 3.

MK-6482 attenuated polycythemia by reducing EPO levels in VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice and in hypoxic Hep3b cells. (A) Serum EPO levels measured by ELISA were significantly increased in VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice, but on treatment with the drug, the elevated EPO levels in VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice decreased to normal WT levels. (B) Epo mRNA levels of Hep3b cells were more than 50-fold higher when grown at 2.5% oxygen concentration than levels grown at atmospheric oxygen concentrations, and the drug treatment significantly reduced the Epo expression levels. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, by ordinary 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons). ns, not significant.

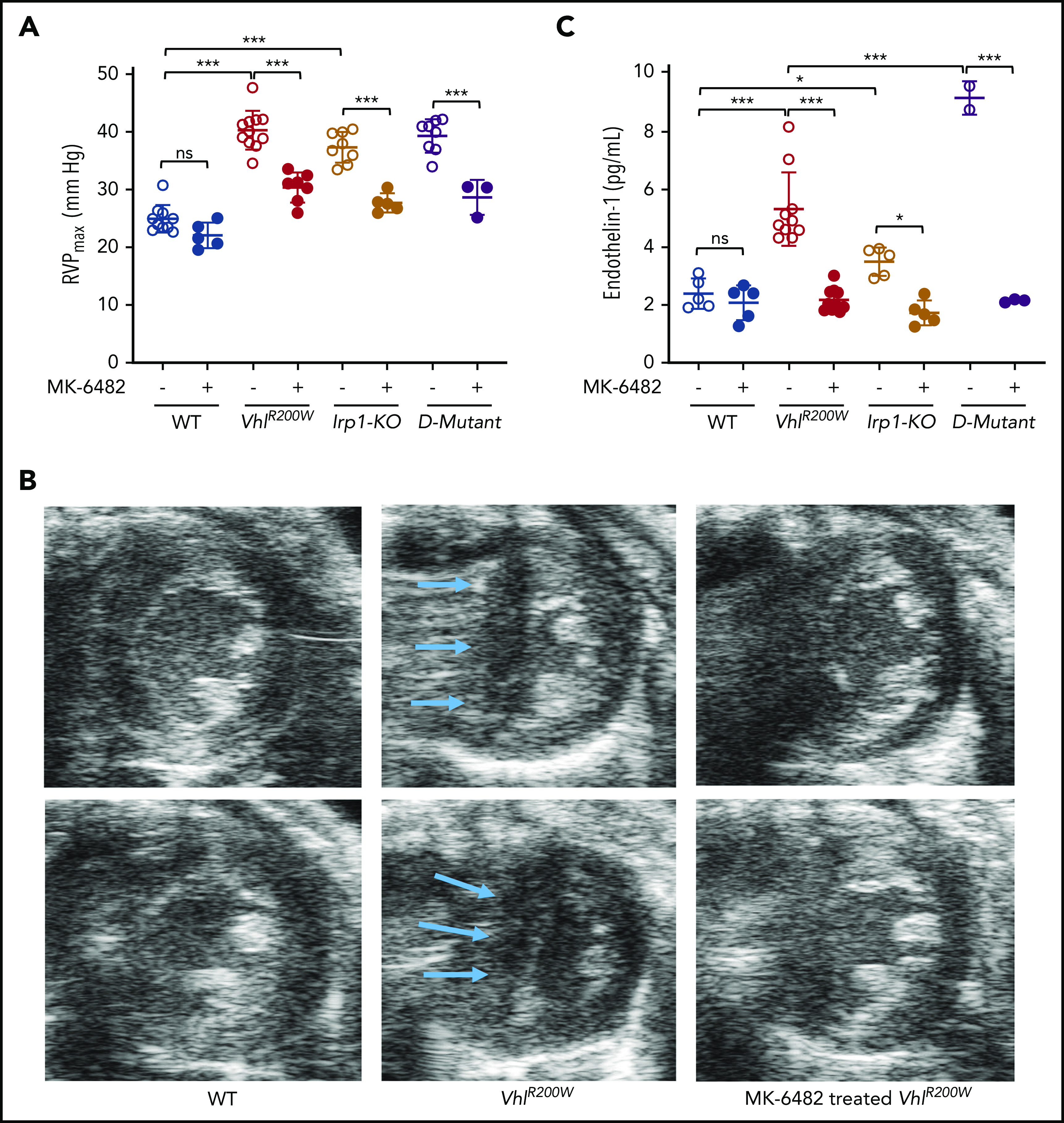

MK-6482 mitigated pulmonary hypertension in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice

We measured intraventricular pressures by the Millar catheterization method. The data for the untreated and vehicle-treated groups of mice did not show any placebo effect (supplemental Figure 5). The right ventricular pressure (RVP) was markedly elevated in untreated or vehicle-treated VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice compared with WT mice (Figure 4A), reconfirming that pulmonary hypertension developed in VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice and demonstrating for the first time that pulmonary hypertension develops in mice with both the Vhl and Irp1 mutations (VhlR200W;Irp1-KO).4,19 However, contrary to the results obtained for hematocrits, the RVPs of VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice4,13 did not increase further in double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. The drug treatment significantly decreased RVPs of the mutant and double-mutant mice, bringing the values close to WT level (Figure 4A). Untreated VhlR200W mice showed systolic flattening of the cardiac interventricular septum (IVS) compared with the normal convex appearance of the IVS in the WT mice throughout systolic contraction (Figure 4B). The D-shaped appearance of the left ventricle in the short-axis views of the untreated VHL mice correlated with elevated RVPs and pulmonary hypertension, as elevated right-side cardiac pressures pushed the IVS toward the left ventricular chamber. Importantly, treatment of the VhlR200W mice with the drug eliminated the development of IVS flattening (Figure 4B), further supporting that MK-6482 is an effective drug for attenuating pulmonary hypertension in the mutant mice.

Figure 4.

MK-6482 treatment reduced pulmonary hypertension in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice and diminished elevated endothelin-1 levels in all 3 mouse models. (A) RVPs measured by catheterization of lightly anesthetized mice showed significantly elevated pressures in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice in comparison with WT mice, and MK-6482 treatment significantly decreased the RVPs, not only in VhlR200W and Irp1-KO mice, but also in double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. (B) Transthoracic echocardiography showed systolic flattening of the IVS in vehicle-treated VhlR200W mice, as indicated by the appearance of an abnormal D-like structure (arrows) compared with the normal convex appearance of the IVS in the WT mice. The D-like structure disappeared and the normal convex shape of the IVS reappeared upon treatment with MK-6482. Representative images from 2 animals of each group are shown. Five mice from each group were tested, except for the drug-treated VhlR200W;Irp1-KO group, in which 3 mice were tested. (C) Serum endothelin-1 levels were elevated in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice compared with the WT mice. When treated with MK-6482, the endothelin-1 levels of the mutant and double-mutant mice reverted to normal WT levels. ns, not significant, *P < .05; ***P < .001 by ordinary 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons). D-mutant, double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mouse.

MK-6482 likely mitigated pulmonary hypertension in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice by reducing endothelin-1 levels

Endothelin-1, a HIF target and potent vasoconstrictor, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension, tissue hypertrophy, and fibrosis.32 We measured endothelin-1 protein levels in the serum of drug- and vehicle-treated WT, VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice and found that the endothelin-1 levels significantly increased in the sera of all the mutant and double-mutant mice compared with the WT animals (Figure 4C). MK-6482 treatment markedly diminished the endothelin-1 level, returning it to near normal levels in all 3 mutant mouse models. In addition, increased endothelin-1 mRNA levels in VhlR200W mouse lungs were significantly reduced by drug treatment (supplemental Figure 6). These results suggested that MK-6482 mitigated pulmonary hypertension, in part by decreasing the levels of endothelin-1 released by pulmonary endothelial cells.

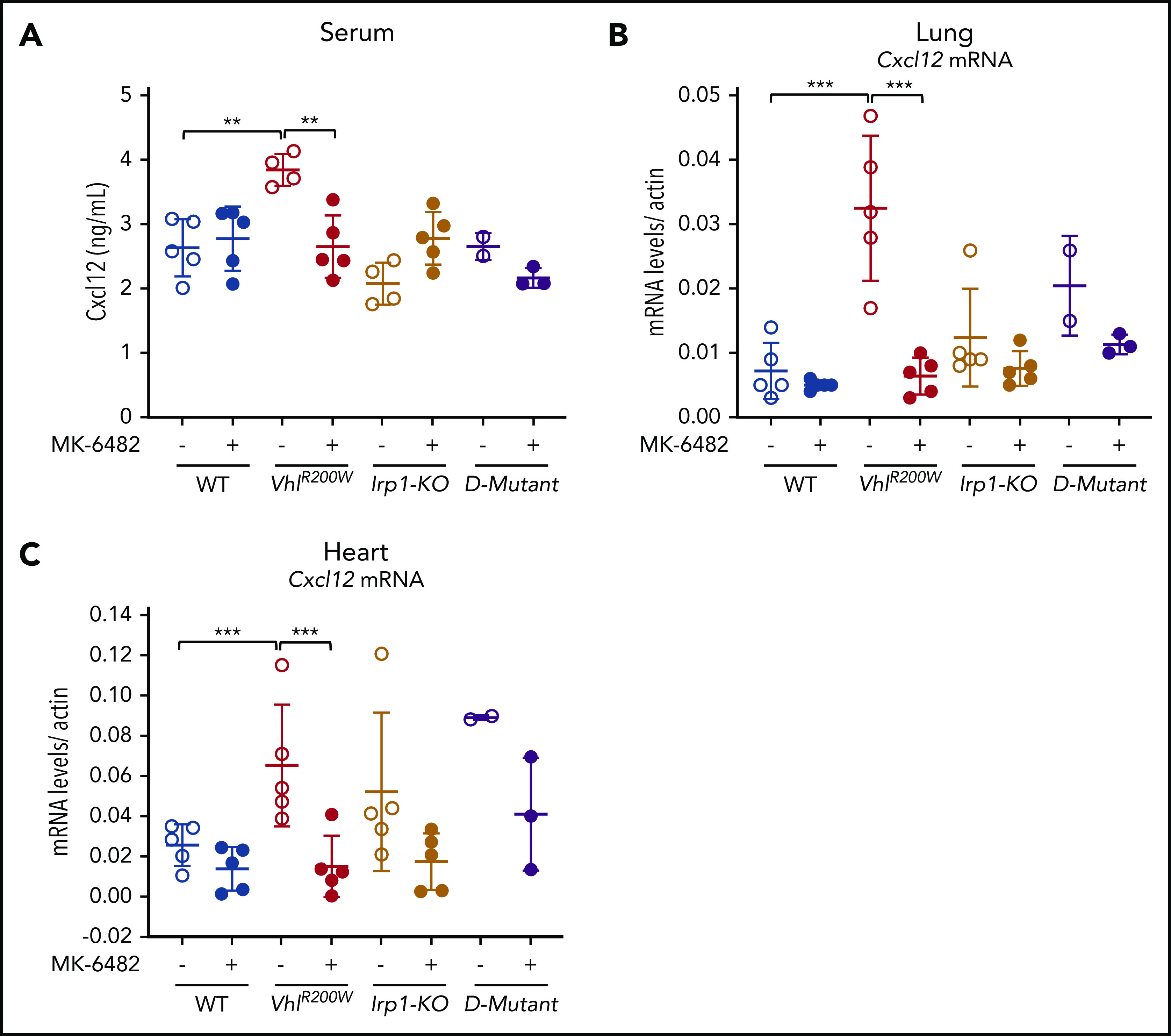

MK-6482 reduced the elevated expression of Cxcl-12 in VhlR200W mice

Aged VhlR200W mice develop pulmonary fibrosis,13 and 1-year-old or older Irp1-KO mice fed with a low-iron diet exhibit cardiac fibrosis.4 There is no known drug that reverses pulmonary fibrosis.62,63 Improved therapies are also needed for cardiac fibrosis.64 Expression of the chemokine CXCL-12, which, in association with its receptor CXCR-4, mediates the influx of fibrocytes into the lung to promote fibroblast proliferation and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,43-45 is induced by HIF-2α.27 Given that MK-6482 disrupts HIF-2α/ARNT heterodimerization51-53 and thereby decreases the expression of HIF-2α target genes, we measured the Cxcl-12 expression levels in vehicle- and drug-treated WT, VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. The mRNA levels of Cxcl-12 in lung and heart tissues and protein expression levels of Cxcl-12 in serum were significantly increased in VhlR200W mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5). On MK-6482 treatment, these increased expression levels of Cxcl-12 in VhlR200W mice reverted to normal WT levels, indicating that MK-6482 may also be effective in reducing cardiac and pulmonary fibrosis in these mice over time.

Figure 5.

MK-6482 decreased the elevated expression of Cxcl-12 in VhlR200W mice. (A) Cxcl-12 protein levels were significantly increased in the serum of VhlR200W mice. When treated with MK-6482, serum Cxcl-12 protein reverted to WT levels. Cxcl-12 mRNA expression levels in lung (B) and heart (C) were elevated in the VhlR200W mice. Drug treatment significantly reduced the Cxcl12 mRNA levels. **P < .01; ***P < .001, by ordinary 1-way ANOVA (multiple comparisons). D-mutant, double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mouse.

Discussion

We worked with mice lacking either Irp1 or functional Vhl, the 2 independent genetic mouse models of polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension that represent models of known human diseases. Phlebotomy therapy has long been used to treat patients with Chuvash polycythemia. However, frequent phlebotomies lead to iron deficiency that can cause 2 conflicting effects on the regulation of HIF-2α. In iron-deficient conditions, increased binding of IRP1 to the HIF-2α IRE at 5′ UTR causes translational repression of HIF-2α.36,38,65,66 On the contrary, iron deficiency reduces PHD2 activity and subsequently promotes the stabilization of HIF-2α.23,24 Thus, it is unclear whether phlebotomy represses or aggravates polycythemia.14 Our results clearly demonstrate that the HIF-2α-inhibitor MK-6482 reduces polycythemia in all 3 mouse models studied. Although Hif-1α deficiency has been shown to cause defective erythropoiesis in yolk sac and embryos,67 our results indicate that Hif-2α is the major player in regulating erythropoiesis in our mouse models. The CBC parameters showed that mild anemia developed in all the experimental mice, including the WT mice, after treatment with MK-6482, indicating that the drug worked on target. Low-grade anemia was also found to be the most common adverse effect in patients with MK-6482-treated clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, and this anemia was managed with EPO replacement rather than dose reduction or discontinuation of treatment.54,68 Pulmonary hypertension is a disease for which there is no cure. However, there are some treatment options available, including oral administration of the drugs ambrisentan, bosentan, or macitentan, all of which are endothelin-1 receptor antagonists.69 Indeed, endothelin-1 plays an important role in the development of pulmonary hypertension.70 In this study, endothelin-1 levels were increased in the mutant and double-mutant mice, and the drug treatment completely prevented the elevation of endothelin-1 levels in all 3 mutant mouse models, suggesting that this drug has a potential for use in treatment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with Chuvash polycythemia and in patients in whom the disease is caused by the upregulation of endothelin-1 or HIF-2α.

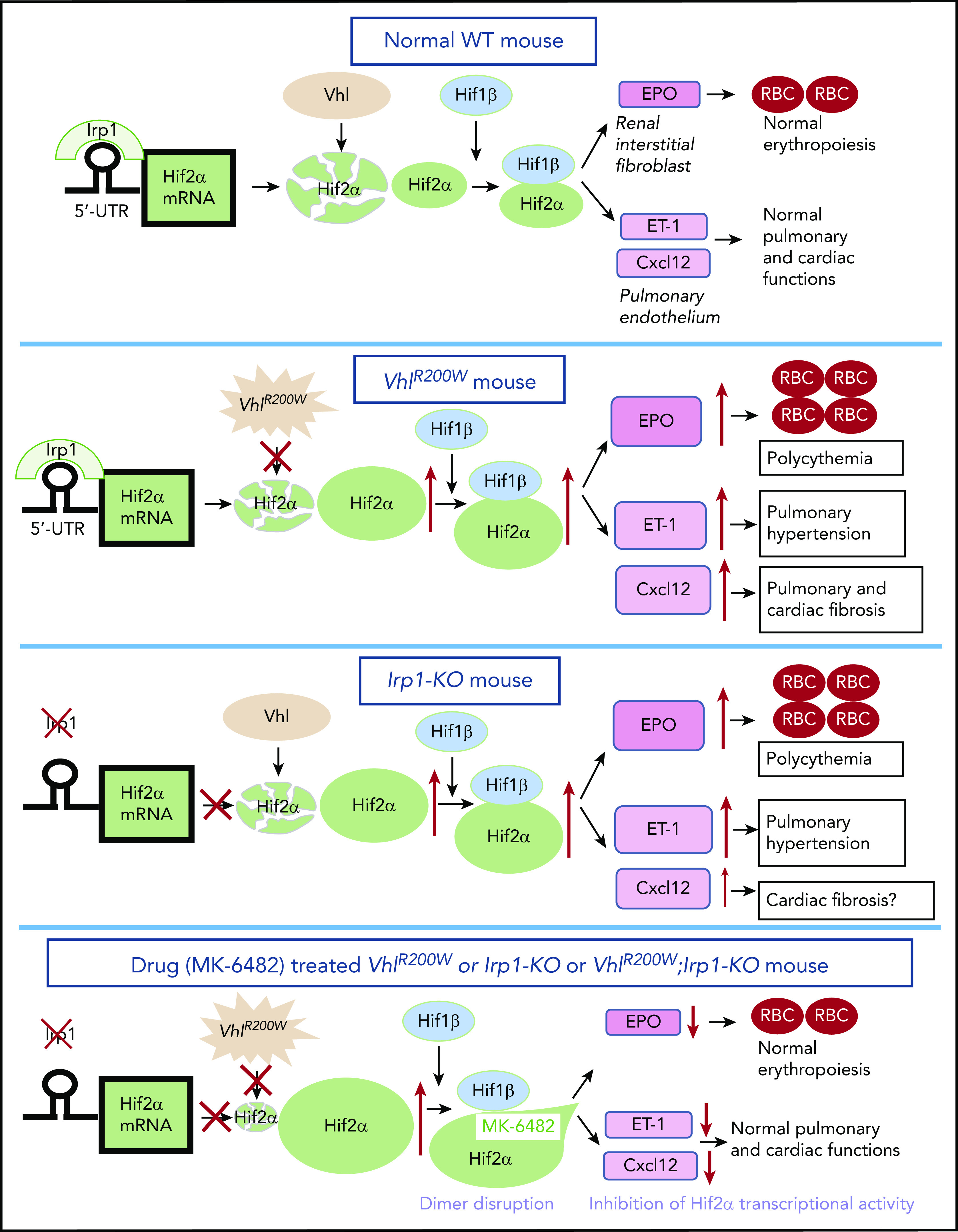

We previously showed that polycythemia develops in VhlR200W mice as early as 6 weeks of age,58 and pulmonary hypertension develops in Irp1-KO mice as early as 3 months of age.4 Because the mice used in this study were 6 to 11 months of age when they received the drug, our results indicate that MK-6482 treatment reversed both polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension phenotypes in the mouse models. The extremely pronounced polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension observed in double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice were also reversed almost completely upon treatment with MK-6482. The mitigation of polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension is attributable to the loss of the Hif-2α transcriptional activity, as MK-6482 binds in the ligand binding pocket of the HIF-2α PAS-B domain and disrupts the HIF-2α/ARNT heterodimerization52 necessary to transcriptionally activate target genes, including EPO, endothelin-1, and Cxcl-12 (Figure 6). Thus, daily oral intake of MK-6482 may represent a new approach to the treatment of Chuvash patients and of other patients who are suffering from forms of polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary fibrosis caused by elevated HIF-2α levels.

Figure 6.

Model for the therapeutic action of MK-6482 in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice. The expression of Hif-2α protein is regulated at multiple levels. Irp1, which is most likely the predominant IRE-binding protein in renal interstitial fibroblast and pulmonary endothelial cells, binds to the Hif-2α-IRE at the 5′ UTR and thus represses Hif-2α translation. Thus, Irp1 deficiency results in an increased Hif-2α expression through derepression of Hif-2α translation. In contrast, the Vhl protein promotes degradation of Hif-2α (as well as Hif-1α) under normoxic conditions. However, VhlR200W does not mediate normal Hif-2α degradation. Thus, either Irp1 deletion or the VhlR200W mutation leads to high levels of Hif-2α and augmented levels of Hif-2α target genes, including EPO, endothelin-1 (ET-1), and Cxcl-12. MK-6482, the second-generation, specific inhibitor of Hif-2α, binds to the internal cavity in the PAS-B domain of Hif-2α, distorting its structure and disrupting the formation of Hif-2α-Hif-1β dimers, thus inhibiting Hif-2α–dependent transcriptional activity and thereby reducing the elevated expression levels of Hif-2α targets in VhlR200W, Irp1-KO, and double-mutant VhlR200W;Irp1-KO mice.

Humans living at high altitudes, including Tibetans, develop genetic adaptations and show improved survival, despite living with comparatively low oxygen availability.71,72 A high-frequency missense mutation in the EGLN1 gene encoding PHD2 is responsible for such adaptive response in Tibetans.73 However, exposure to high-altitude hypoxia causes polycythemia characterized by augmented erythropoiesis and elevated hematocrit levels, and pulmonary hypertension10,74 associated with elevated RVPs and increased endothelin-1 levels75 in most nonadapted people. Our results suggest that treatment with the specific Hif-2α inhibitor MK-6482 can also mitigate hypoxic polycythemia and hypoxic pulmonary hypertension, indicating that this drug may be used to treat high-altitude polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in nonadapted individuals. However, because this class of drugs may also cause defects in respiratory control, some caution should be taken, and individuals should be monitored carefully when MK-6482 is used as a therapy for patients who are dependent on hypoxic ventilatory drive.49

An interesting observation we had here regarding the regulation of the Hif-2α targets EPO and endothelin-1 is that the translational inhibition of Hif-2α through binding of Irp1 to Hif-2α-IRE at the 5′ UTR plays a more pronounced role in regulating EPO than the Vhl protein–mediated proteasomal degradation of Hif-2α, whereas the reverse is true of the regulation of endothelin-1. A major difference between these 2 pathways for downregulation of Hif-2α is that the Irp1/Hif-2α IRE binding pathway specifically decreases Hif-2α expression, but Hif-1α expression remains unaffected, because Hif-1α has no IRE, whereas the Vhl protein–mediated pathway degrades both Hif-1α and -2α. In our previous work,58 we showed that Tempol, a small, stable nitroxide molecule76 corrects polycythemia in VhlR200W mice via translational repression of Hif-2α expression, but it did not attenuate pulmonary hypertension in those mice (M.C.G., unpublished results, 15 December 2015). As we observed in our previous study,58 the serum EPO levels increased significantly, but only slightly in untreated VhlR200W mice, compared with WT animals. These results are consistent with a previously observed hypersensitivity to EPO and involvement of the JAK/STAT5 pathway.77-79 Notably, inhibition of JAK-1 and JAK-2 by the inhibitor ruxolitinib was shown to reduce the severity of polycythemia in 3 patients.80 Our results, however, imply that increased Hif-2α expression is the predominant factor that causes polycythemia in VhlR200W mice and clearly in Irp1-KO mice.

Suppression of Hif-2α signaling by a small-molecule Hif-2α inhibitor has recently been found to diminish pulmonary hypertension in rodents exposed to hypoxia for 4 to 5 weeks.33 In another study, pharmacological inhibition of Hif-2α by a Hif-2α translational inhibitor C76 has been observed to reduce pulmonary hypertension in prolyl hydroxylase-2–deficient Egln1Tie2Cre mice and Sugen 5416/hypoxia PAH rats.30 Our study with 3 independent mouse models that had mutations comparable to those in 2 defined groups of patients suggested that polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary and cardiac fibrosis can be mitigated by treatment with a small-molecule inhibitor of Hif-2α, MK-6482, a drug that has been shown to have a favorable safety profile in renal cancer trials.53,54 Thus, multiple patients with pulmonary hypertension and/or polycythemia caused by mutations of critical genes known to be involved in the HIF-2α pathway, and others as yet undefined, may benefit from the potent and selective Hif-2α inhibitor MK-6482, which showed promising efficacy and tolerability in humans.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Peloton Therapeutics Inc (Dallas, TX) and Merck & Co Inc (Kenilworth, NJ) for their generous gift of the drug MK-6482 (PT2977); Peter Robbins and Mary Slingo of Oxford University for providing the heterozygous VhlR200W mice; Laura Schmidt of Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research for helping to obtain the drug; Eric A. Meade of Merck for critically reading the manuscript; and members of the T.A.R. laboratory for contributing to constructive discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Intramural Research Program (grant ZIAHD001602).

Footnotes

An embryo of the IRP1-knockout mouse, bred in our laboratory, has been deposited in the Mutant Mouse Resource and Research Center (MMRRC), supported by the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.C.G. designed the project, performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; D.-L.Z. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and reviewed the paper; W.H.O. performed experiments and reviewed the paper; A.N. and D.A.S. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and reviewed the paper; W.M.L. provided guidance on drug use and formulation and reviewed the paper; and T.A.R. designed and supervised the project and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tracey A. Rouault, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bldg 35A, Rm 2D824, Bethesda, MD 20892-3755; e-mail rouault@mail.nih.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bento C. Genetic basis of congenital erythrocytosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018;40(suppl 1):62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira JL, Coon LM, Frederick LA, et al. Genotype-Phenotype Correlation of Hereditary Erythrocytosis Mutations, a single center experience. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(8):1029-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oskarsson GR, Oddsson A, Magnusson MK, et al. Predicted loss and gain of function mutations in ACO1 are associated with erythropoiesis. Commun Biol. 2020;3(1):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh MC, Zhang DL, Jeong SY, et al. Deletion of iron regulatory protein 1 causes polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in mice through translational derepression of HIF2α. Cell Metab. 2013;17(2):271-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. The Genomics and Genetics of Oxygen Homeostasis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2020;21(1):183-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallik N, Sharma P, Kaur Hira J, et al. Genetic basis of unexplained erythrocytosis in Indian patients. Eur J Haematol. 2019;103(2):124-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zmajkovic J, Lundberg P, Nienhold R, et al. A Gain-of-Function Mutation in EPO in Familial Erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):924-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson SA, Nizzi CP, Chang YI, et al. The IRP1-HIF-2α axis coordinates iron and oxygen sensing with erythropoiesis and iron absorption. Cell Metab. 2013;17(2):282-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson N, Pantopoulos K. IRP1 regulates erythropoiesis and systemic iron homeostasis by controlling HIF2α mRNA translation. Blood. 2013;122(9):1658-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassoun PM, Schumacker PT. Update in pulmonary vascular diseases 2013. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(7):738-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girerd B, Lau E, Montani D, Humbert M. Genetics of pulmonary hypertension in the clinic. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(5):386-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sable CA, Aliyu ZY, Dham N, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure and iron deficiency in patients with upregulation of hypoxia sensing due to homozygous VHL(R200W) mutation (Chuvash polycythemia). Haematologica. 2012;97(2):193-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickey MM, Richardson T, Wang T, et al. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation promotes pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(3):827-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordeuk VR. Chuvash polycythemia: diagnosis and management. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2011;9(12):929-930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, Dalaan AM, Satoh T, Galiè N. Treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(4):323-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diab N, Hassoun PM. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: screening challenges in systemic sclerosis and future directions. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1700522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Nouraie M, et al. The heterozygote advantage of the Chuvash polycythemia VHLR200W mutation may be protection against anemia. Haematologica. 2011;96(9):1371-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sergeyeva A, Gordeuk VR, Tokarev YN, Sokol L, Prchal JF, Prchal JT. Congenital polycythemia in Chuvashia. Blood. 1997;89(6):2148-2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickey MM, Lam JC, Bezman NA, Rathmell WK, Simon MC. von Hippel-Lindau mutation in mice recapitulates Chuvash polycythemia via hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha signaling and splenic erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(12):3879-3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyers M, Rottapel R. VHL: a very hip ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(22):12230-12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krek W. VHL takes HIF’s breath away. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(7):E121-E123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouvès A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouysségur J. HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. EMBO J. 2003;22(16):4082-4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson RJ, McKie AT. Iron and oxygen sensing: a tale of 2 interacting elements? Metallomics. 2015;7(2):223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107(1):43-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mole DR, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of HIF by the von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor: implications for cellular oxygen sensing. IUBMB Life. 2001;52(1-2):43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee P, Chandel NS, Simon MC. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(5):268-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin SK, Diamond P, Williams SA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 is a novel regulator of aberrant CXCL12 expression in multiple myeloma plasma cells. Haematologica. 2010;95(5):776-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaelin WG Jr. The VHL Tumor Suppressor Gene: Insights into Oxygen Sensing and Cancer. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2017;128:298-307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 Hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) Deficiency in Endothelial Cells and Hematopoietic Cells Induces Obliterative Vascular Remodeling and Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Mice and Humans Through Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2447-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai Z, Zhu MM, Peng Y, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Vascular Remodeling and Right Heart Failure in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension with a HIF-2α Inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(11):1423-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapitsinou PP, Rajendran G, Astleford L, et al. The Endothelial Prolyl-4-Hydroxylase Domain 2/Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Axis Regulates Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36(10):1584-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bushuev VI, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Endothelin-1, vascular endothelial growth factor and systolic pulmonary artery pressure in patients with Chuvash polycythemia. Haematologica. 2006;91(6):744-749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu CJ, Poth JM, Zhang H, et al. Suppression of HIF2 signalling attenuates the initiation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(6):1900378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Polyakova LA, Nouraie M, Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Complications in children and adolescents with Chuvash polycythemia. Blood. 2015;125(2):414-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(8):406-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghosh MC, Zhang DL, Rouault TA. Iron misregulation and neurodegenerative disease in mouse models that lack iron regulatory proteins. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;81:66-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2010;142(1):24-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang DL, Ghosh MC, Rouault TA. The physiological functions of iron regulatory proteins in iron homeostasis - an update. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkinson N, Pantopoulos K. The IRP/IRE system in vivo: insights from mouse models. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyron-Holtz EG, Ghosh MC, Iwai K, et al. Genetic ablations of iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 reveal why iron regulatory protein 2 dominates iron homeostasis. EMBO J. 2004;23(2):386-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson CP, Shen M, Eisenstein RS, Leibold EA. Mammalian iron metabolism and its control by iron regulatory proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(9):1468-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bordenave J, Thuillet R, Tu L, et al. Neutralization of CXCL12 attenuates established pulmonary hypertension in rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(3):686-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antoniou KM, Soufla G, Lymbouridou R, et al. Expression analysis of angiogenic growth factors and biological axis CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51(1):71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie LZL. Role of CXCL12/CXCR4-Mediated Circulating Fibrocytes in Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Biomed (Syd). 2017;2:134-139. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li F, Xu X, Geng J, Wan X, Dai H. The autocrine CXCR4/CXCL12 axis contributes to lung fibrosis through modulation of lung fibroblast activity. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(3):1844-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, et al. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(3):438-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Key J, Scheuermann TH, Anderson PC, Daggett V, Gardner KH. Principles of ligand binding within a completely buried cavity in HIF2alpha PAS-B. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(48):17647-17654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheuermann TH, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Guo Y, Bruick RK, Gardner KH. Artificial ligand binding within the HIF2alpha PAS-B domain of the HIF2 transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(2):450-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng X, Prange-Barczynska M, Fielding JW, et al. Marked and rapid effects of pharmacological HIF-2α antagonism on hypoxic ventilatory control. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2237-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaelin WG Jr. HIF2 Inhibitor Joins the Kidney Cancer Armamentarium. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(9):908-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Courtney KD, Infante JR, Lam ET, et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation Trial of PT2385, a First-in-Class Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α Antagonist in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(9):867-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng Z, Zou X, Chen Y, Wang H, Duan Y, Bruick RK. Modulation of HIF-2α PAS-B domain contributes to physiological responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(52):13240-13245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu R, Wang K, Rizzi JP, et al. 3-[(1S,2S,3R)-2,3-Difluoro-1-hydroxy-7-methylsulfonylindan-4-yl]oxy-5-fluorobenzonitrile (PT2977), a Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2α (HIF-2α) Inhibitor for the Treatment of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Med Chem. 2019;62(15):6876-6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choueiri TP, Plimack ER, Bauer TM, et al. Phase I/II study of the oral HIF-2α inhibitor MK-6482 in patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38. Abstract 611. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garje R, An JJ, Sanchez K, et al. Current Landscape and the Potential Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors and Selenium in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jonasch EDF, Iliopoulos O, Rathmell WK, et al. Phase II study of the oral HIF-2α inhibitor MK-6482 for Von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated renal cell carcinoma [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 suppl). Abstract 5003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slingo M, Cole M, Carr C, et al. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation in mice alters cardiac substrate and high-energy phosphate metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311(3):H759-H767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghosh MC, Zhang DL, Ollivierre H, Eckhaus MA, Rouault TA. Translational repression of HIF2α expression in mice with Chuvash polycythemia reverses polycythemia. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(4):1317-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang DL, Ghosh MC, Ollivierre H, Li Y, Rouault TA. Ferroportin deficiency in erythroid cells causes serum iron deficiency and promotes hemolysis due to oxidative stress. Blood. 2018;132(19):2078-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stembridge M, Williams AM, Gasho C, et al. The overlooked significance of plasma volume for successful adaptation to high altitude in Sherpa and Andean natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(33):16177-16179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rankin EB, Biju MP, Liu Q, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(4):1068-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(8):797-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez FJ, Collard HR, Pardo A, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park S, Nguyen NB, Pezhouman A, Ardehali R. Cardiac fibrosis: potential therapeutic targets. Transl Res. 2019;209:121-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanchez M, Galy B, Muckenthaler MU, Hentze MW. Iron-regulatory proteins limit hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha expression in iron deficiency. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(5):420-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmer M, Ebert BL, Neil C, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of HIF-2a translation link its 5’UTR iron-responsive element to oxygen sensing. Mol Cell. 2008;32(6):838-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoon D, Pastore YD, Divoky V, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 deficiency results in dysregulated erythropoiesis signaling and iron homeostasis in mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(35):25703-25711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choueiri TK, Kaelin WG Jr.. Targeting the HIF2-VEGF axis in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1519-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Belge C, Delcroix M. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension with the dual endothelin receptor antagonist macitentan: clinical evidence and experience. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2019;13:1753466618823440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chester AH, Yacoub MH. The role of endothelin-1 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014(2):62-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(suppl 1):8655-8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, et al. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science. 2010;329(5987):72-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lorenzo FR, Huff C, Myllymäki M, et al. A genetic mechanism for Tibetan high-altitude adaptation. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):951-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu XQ, Jing ZC. High-altitude pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2009;18(111):13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berger MM, Dehnert C, Bailey DM, et al. Transpulmonary plasma ET-1 and nitrite differences in high altitude pulmonary hypertension. High Alt Med Biol. 2009;10(1):17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghosh MC, Tong WH, Zhang D, et al. Tempol-mediated activation of latent iron regulatory protein activity prevents symptoms of neurodegenerative disease in IRP2 knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(33):12028-12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ang SO, Chen H, Gordeuk VR, et al. Endemic polycythemia in Russia: mutation in the VHL gene. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28(1):57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, et al. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet. 2002;32(4):614-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russell RC, Sufan RI, Zhou B, et al. Loss of JAK2 regulation via a heterodimeric VHL-SOCS1 E3 ubiquitin ligase underlies Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Med. 2011;17(7):845-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou AW, Knoche EM, Engle EK, Ban-Hoefen M, Kaiwar C, Oh ST. Clinical Improvement with JAK2 Inhibition in Chuvash Polycythemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):494-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.