Acetyl-CoA is a key energy metabolite that links metabolism with signaling, chromatin structure, and transcription. This central position endows acetyl-CoA with an important regulatory role: the level of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA reflects the energetic and metabolic state of the cell (1–3). Acetyl-CoA also serves as a substrate for lysine (K) acetyltransferases (KATs) that catalyze the transfer of acetyl groups to lysines in a vast array of proteins, including histones. Fluctuations in the concentration of acetyl-CoA, reflecting the changes in the metabolic state of the cell, are translated into dynamic protein acetylations that regulate a variety of cell functions, including transcription and metabolic reprogramming. Histone acetylation is a dynamic modification that occurs on all four core histones; it affects chromatin structure and regulates gene expression by at least two mechanisms. First, acetylation of the lysine residues of the histone tails neutralizes positive charges and weakens interactions between histones and DNA and between neighboring nucleosomes. Second, bromodomain-containing proteins, such as Swi2p subunit of the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex, bind acetyl-lysine motifs in the histone tails and facilitate transcription by repositioning or evicting nucleosomes (4). The level of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA regulates the global acetylation of chromatin histones and the transcription of many genes (5–7). The KAT complex SAGA and its catalytic subunit Gcn5p are likely responsible for coupling histone acetylation with acetyl-CoA levels (7). As transcriptional induction of histone genes during S phase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is associated with the recruitment of Gcn5p to histone promoters (8), we hypothesized that histone transcription is regulated by the acetylation status of chromatin histones in the promoters of histone genes. If this assumption is correct, then reduced levels of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA would result in decreased expression of histone genes. Since reduced histone expression globally affects chromatin structure (9), and increases mitochondrial activity and ATP synthesis (10), we tested whether reduced synthesis of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA reduces histone transcription and is compensated for by elevated respiration and ATP synthesis. Here we show that reduced synthesis of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA leads to reduced acetylation of chromatin histones in the promoters of histone genes, and decreased histone transcription. The globally altered chromatin structure triggers mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration, and leads to increased synthesis of ATP. Together, our data indicate that the depletion of the energy metabolite acetyl-CoA is compensated for by the induction of ATP synthesis.

Cells transcribe histones during S phase to maintain the balance between histone and DNA synthesis that is needed for chromatin assembly. The correct cell cycle-dependent transcription of histone genes is mediated by histone-specific transcription factors Spt10p/Spt21p (8, 11, 12). Spt21p accumulates only during S phase, when it is recruited to the promoters of histone genes through its interaction with Spt10p. Spt10p/Spt21p subsequently recruit KAT Gcn5p and an additional KAT that has not yet been identified. It is likely that the Spt10p/Spt21p-associated KATs then acetylate histones in the promoters of histone genes to activate histone transcription; however, this acetylation has not been demonstrated (8). Several other transcriptional regulators are recruited to histone promoters, including chromatin remodeling complex Swi/Snf (11, 12, 13). Since Swi/Snf binds to acetylated lysines in histones and frequently functions in concert with SAGA, it is likely that Gcn5p/SAGA-mediated acetylation of histones in the promoters of histone genes facilitates recruitment of Swi/Snf to activate histone transcription.

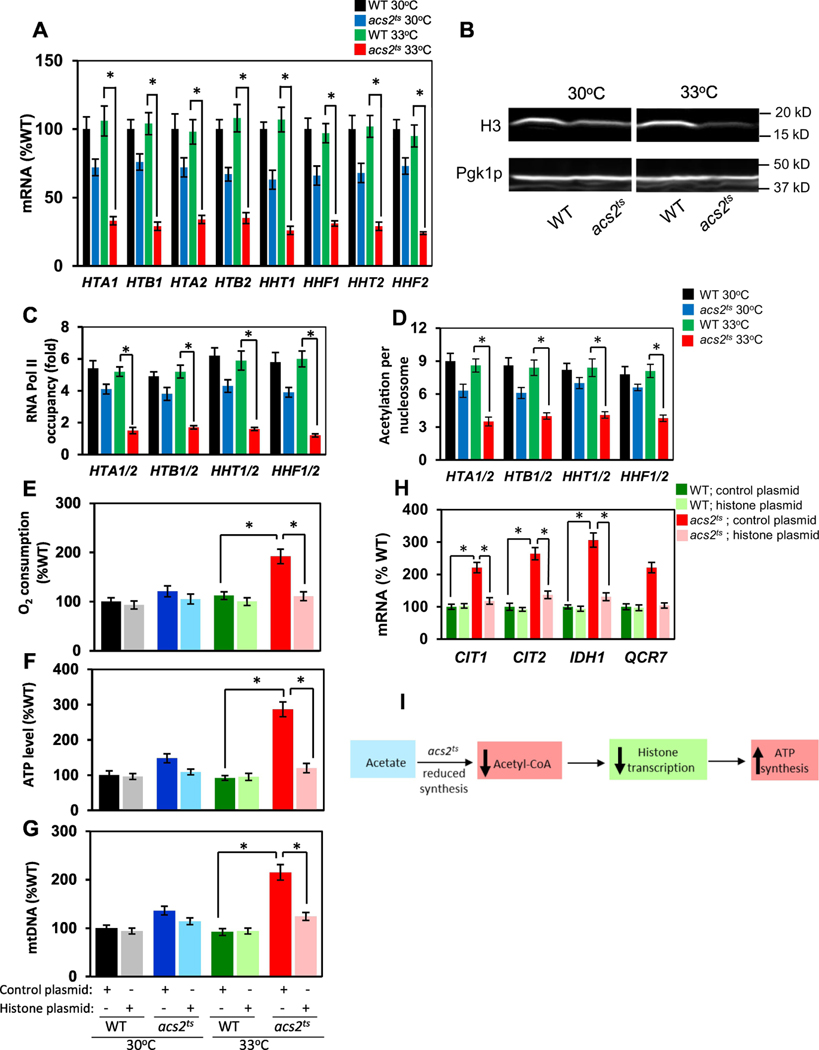

To determine whether the nucleocytosolic level of acetyl-CoA regulates the transcription of histone genes, we used the acs2ts allele (5) (Supplemental material). ACS2 encodes nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 responsible for the synthesis of acetyl-CoA from acetate and CoA. Since yeast mitochondrial and nucleocytosolic pools of acetyl-CoA are distinct and isolated, Acs2p is the sole source of acetyl-CoA in the nucleocytosolic compartment. The acs2ts mutant displays severe global histone hypoacetylation and transcriptional defects at restrictive temperatures. acs2ts cells grow at the wild-type rate at 30°C, but are not able to grow at the restrictive temperature of 37°C (5, 14). We found that histone mRNA levels are already slightly reduced at 30°C in acs2ts cells in comparison with wild type cells, and significantly more reduced at the semipermissive temperature of 33°C (Fig. 1A). In acs2ts cells at 33°C, mRNAs of individual histones were reduced to 25–35% of mRNA levels in wild-type cells at 30°C. This reduction in transcription of histone genes was also evident at the protein level of histone H3; the H3 protein level in acs2ts cells was slightly reduced at 30°C and more significantly reduced at 33°C (Fig. 1B). We selected histone H3 for this analysis, because the antibody we used recognizes the C-terminal region of H3, which is not posttranslationally modified, and the signal obtained with this antibody represents the total H3 level.

Figure 1. Acs2p inactivation downregulates transcription of histone genes and elevates respiration.

(A) Relative histone mRNA levels; the results are shown relative to the value for the wild-type (WT) strain grown at 30°C. (B) Histone H3 protein levels; western blot analysis was performed three times, and representative results are shown. (C) Occupancy of RNA Pol II at histone promoters. (D) H3K14 acetylation in histone promoters. (A-D) WT and acs2ts cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C and 33°C. (E) Relative oxygen consumption, (F) ATP levels, (G) mtDNA copy numbers, and (H) mRNA levels of respiratory genes in wild-type (WT) and acs2ts cells containing either the control plasmid or a low-copy histone plasmid expressing all four core histone genes (plasmid pJH33; Blackwell et al., 2007). The cells were pregrown under selection in SC medium, inoculated to an A600 of 0.1 into YPD medium and grown for two generations at 33°C. (I) Model depicting the relationship between acetyl-CoA synthesis, histone transcription, and ATP synthesis. (A, C, D, E, F, G, H) The experiments were repeated three times, and the results are shown as means ± SD. Values that are statistically different (p < 0.05) from each other are indicated by a bracket and asterisk.

To test whether the reduced histone mRNA levels are due to a defect in the assembly of the preinitiation complex (PIC) at the histone promoters, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to determine the degree of RNA Pol II recruitment to the histone promoters (Fig. 1C). In agreement with histone mRNA levels, the occupancy of RNA Pol II at the histone promoters in acs2ts cells was significantly reduced at 33°C, indicating that the decreased nucleocytosolic level of acetyl-CoA affects PIC assembly and transcriptional initiation. To test whether the decreased level of acetyl-CoA in acs2ts cells at 33°C affects the acetylation of chromatin histones in the promoters of histone genes, we used ChIP to evaluate the occupancy of histone H3 acetylated at lysine 14 (acH3K14) in the histone promoters (Fig. 1D). To account for differences in nucleosome density due to differences in histone levels between WT and acs2ts cells at 30°C and 33°C, we corrected the acH3 occupancy for histone H3 content, and generated values that represent acetylation per nucleosome (Fig. 1D). Histone H3 acetylation per nucleosome in the promoters of histone genes was significantly reduced in acs2ts cells in comparison with WT cells at 33°C. Taken together, these results indicate that the reduced nucleocytosolic level of acetyl-CoA in acs2ts cells at 33°C results in decreased transcription of histones due to hypoacetylation of chromatin histones in the promoters of histone genes.

Decreased histone levels are associated with reduced chromatin nucleosome density and globally altered chromatin structure. From the perspective of nucleosomal architecture, genes can be classified as growth genes or stress genes (9). Growth genes are expressed at high levels and feature a nucleosome-free region, which allows for the unobstructed binding of transcription factors. The stress genes are expressed at lower levels and their promoters are dominated by delocalized nucleosomes. Consequently, stress genes are regulated by factors that affect chromatin structure, including histone levels. As the respiratory genes in S. cerevisiae belong to the stress category (15), decreased expression of histones triggers the transcription of respiratory genes and induces respiration (10). To test whether the decreased histone transcription in acs2ts cells represents the mechanism responsible for elevated mitochondrial respiration and metabolism, we transformed WT and acs2ts cells with either a control plasmid or a low-copy-number plasmid encoding all four core histones. We found that even the slightly increased expression of histones from the low-copy-number plasmid suppressed the respiratory phenotypes of acs2ts cells at 33°C and significantly reduced oxygen consumption, ATP levels, mtDNA copy number, and mRNA levels of several genes encoding enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Fig. 1E-H). On the basis of these results, we propose a model in which a reduced synthesis of nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA results in reduced histone transcription, globally affected chromatin structure, and increased transcription of respiratory genes, mitochondrial respiration, and ATP synthesis (Fig. 1I). This study identifies nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA as an indicator of the energetic state of the cell and as a regulator of chromatin structure and mitochondrial metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Reduced nucleocytosolic acetyl-CoA synthesis downregulates histone transcription

Decreased acetyl-CoA levels affect PIC assembly at histone promoters

Decreased acetyl-CoA reduces histone acetylation at histone promoters

Decreased histone levels induce respiration and ATP synthesis

Decreased acetyl-CoA synthesis is compensated for by elevated ATP synthesis

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Pemberton and Boeke for strains and plasmids. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health GM106324 and GM135839 (to A.V).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cai L, Tu BP, On acetyl-CoA as a gauge of cellular metabolic state. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 76, 195–202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg T. et al. , Nucleocytosolic depletion of the energy metabolite acetyl-CoA stimulates autophagy and prolongs lifespan. Cell Metab. 19, 431–444 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrocola F, Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Madeo F, Kroemer G, Acetyl coenzyme A: a central metabolite and second messenger. Cell Metab. 21, 805–821 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutta A, Abmayr SM, Workman JL, Diverse activities of histone acylations connect metabolism to chromatin function. Mol. Cell. 63, 547–552 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi H, McCaffery JM, Irizarry RA, Boeke JD, Nucleocytosolic acetyl-coenzyme a synthetase is required for histone acetylation and global transcription. Mol. Cell. 23, 207–217 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB, ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 324, 10761080 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai L, Sutter BM, Li B, Tu BP, Acetyl-CoA induces cell growth and proliferation by promoting the acetylation of histones at growth genes. Mol. Cell 42, 426–437 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurat CF, Lambert J-P, Petschnigg J, Friesen H, Pawson T, Rosebrock A, Gingras A-C, Fillingham J, Andrews B, Cell cycle-regulated oscillator coordinates core histone gene transcription through histone acetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 14124–14129 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rando OJ, Winston F, Chromatin and transcription in yeast. Genetics 190, 351–387 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galdieri L, Zhang T, Rogerson D, Vancura A, Reduced histone expression or a defect in chromatin assembly induces respiration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36, 1064–1077 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson PR, Ganguli D, Nagarajavel V, Clark DJ, Regulation of histone gene expression in budding yeast. Genetics 191, 7–20 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurat CF, Recht J, Radovani E, Durbic T, Andrews B, Fillingham J, Regulation of histone gene transcription in yeast. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 599–613 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F, Zhang K, Grunstein M, Acetylation in histone H3 globular domain regulates gene expression in yeast. Cell 121, 375–385 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galdieri L, Vancura A, Acetyl-CoA carboxylase regulates global histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 28, 23865–23876 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsankov AM, Thompson DA, Socha A, Regev A, Rando OJ, The role of nucleosomes positioning in the evolution of gene regulation. PLoS Biology 8, e1000414 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.