Abstract

Coarctation of the aorta is a constriction of the aorta located near the ligamentum arteriosum and the origins of the left subclavian artery. This condition may be associated with other congenital disease. The mean age of death for persons with this condition is 34 years if untreated, and is usually due to heart failure, aortic dissection or rupture, endocarditis, endarteritis, cerebral hemorrhage, ischemic heart disease, or concomitant aortic valve disease in uncomplicated cases. Symptoms may not be present in adults. Diminished and delayed pulses in the right femoral artery compared with the right radial or brachial artery are an important clue to the presence of a coarctation of the aorta, as are the presence of a systolic murmur over the anterior chest, bruits over the back, and visible notching of the posterior ribs on a chest x‐ray. In many cases a diagnosis can be made with these findings. Two‐dimensional echocardiography with Doppler interrogation is used to confirm the diagnosis. Surgical repair and percutaneous intervention are used to repair the coarctation; however, hypertension may not abate. Because late complications including recoarctation, hypertension, aortic aneurysm formation and rupture, sudden death, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and cerebrovascular accidents may occur, careful follow‐up is required.

Figure 1 shows the chest x‐ray of a patient with hypertension. Coarctation of the aorta is a discrete narrowing of the aorta most frequently located near the ligamentum arteriosum (Figure 2). The ligamentum arteriosum, a remnant of the ductus arteriosus of fetal circulation, is a fibrous attachment between the thoracic aorta and pulmonary trunk just beyond the origins of the left subclavian artery. Coarctation may occur proximally (preductal) or more commonly distally (postductal) to this area. When the coarctation is distal to the left subclavian artery, the left subclavian artery is dilated and an extensive collateral circulation forms through the left subclavian, internal thoracic artery, intercostal, and scapular arteries. Rarely, coarctation occurs in the abdominal aorta, accounting for 0.5%–2% of all cases. 1

Figure 1.

A 24‐year‐old patient presents with hypertension and this chest x‐ray. What finding supports a secondary cause of hypertension? The arrows show rib notching.

Figure 2.

Postductal coarctation of the aorta

Coarctation of the aorta in adults is the most common congenital lesion that hypertension specialists should recognize. 2 , 3 It accounts for a 0.2% prevalence of hypertension in adults. 4 The two forms of coarctation occur with equal frequency. A simple coarctation, which is usually found in adults, is not associated with other intracardiac lesions. Usually seen in infancy, complex coarctation usually presents with heart failure and there may be additional congenital abnormalities, including ventricular septal defects, aortic stenosis, subaortic stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, or an anomalous original of the right subclavian artery. A bicuspid aortic valve occurs among 50%–85% of cases. 5 Up to 5% of persons with coarctation of the aorta will have a Berry aneurysm in the circle of Willis.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Approximately 75% of patients with coarctation are male. It may occur in other, less common syndromes. 6 , 7

NATURAL HISTORY

The mean survival of untreated coarctation is 34 years. 8 About 75% will die by age 46 years and 90% by age 58 years. Death is due to heart failure, aortic dissection or rupture, endocarditis, endarteritis, cerebral hemorrhage, ischemic heart disease, or concomitant aortic valve disease. During pregnancy, women are at risk for aortic dissection.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of coarctation before repair are summarized in Figure 3. 9 Dyspnea and fatigue are the most common symptoms. Cold feet are also commonly noted. Symptoms are often not present in young adults.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of preoperative symptoms (N=61) Data derived from J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:525–531. 9

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Although aortic coarctation is relatively rare compared with other causes of secondary hypertension, practitioners should be cognizant of elements of physical examination that can provide important clues to this diagnosis. For example, systolic blood pressure is higher in the right arm compared with right leg, but diastolic blood pressure levels are similar. 10 , 11 When a coarctation is proximal to the left subclavian artery, systolic blood pressure is higher in the right arm than the left arm. This is less common. Pulses are delayed and less intense over the right femoral artery compared with the radial or right brachial artery. Also, the right and left brachial artery pulsations should be compared to determine if the coarctation is proximal (decreased or absent left brachial pulsation), distal (no difference in brachial pulsations), or distal with anomalous right subclavian artery after the coarctation (decreased or absent right brachial pulsation). Pulsatile, U‐shaped, corkscrew arterioles are seen in funduscopic examination. Prominent pulsations are usually present in the suprasternal notch. A sustained left ventricular apical impulse may be present with an S4 gallop with left ventricular hypertrophy.

Several murmurs can be present depending on the presence of additional congenital abnormalities. A grade II‐VI systolic murmur, sometimes associated with a thrill, is often present along the left sternal border and the mid‐back between the left scapula and spine. The murmur radiates to the neck. A delayed‐onset, continuous crescendo‐decrescendo murmur can be heard over the back due to the enlargement of the collateral circulation. A bicuspid aortic valve occurs in 50%–80% of patients with coarctation of the aorta. 5 If a bicuspid aortic valve is present, a systolic murmur is heard with aortic stenosis or a diastolic decrescendo murmur with aortic insufficiency. An aortic ejection sound and increased S2 may be present.

RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Two common chest x‐ray clues are rib notching (Figure 1) and the figure‐3 sign. Usually observed after 6 years of age, rib notching affects the inferior posterior ribs (numbers 3–8) and is due to collateral flow through the posterior intercostal arteries. Rib involvement is bilateral with distal coarctation, right‐sided with proximal coarctation, and left‐sided with distal coarctation with anomalous right subclavian artery. The figure‐3 sign is due to a dilated subclavian artery and postcoarctation aortic dilatation.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis can usually be made on physical findings and a chest x‐ray. An echocardiogram with Doppler usually can detect coarctation of the aorta. Doppler techniques record the transcoarctation pressure gradient. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can also delineate anatomic information. Magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography compare equally well to contrast aortography for most measurements. 12

OPERATIVE REPAIR

A transcoarctation pressure gradient >20 mm Hg with proximal systemic hypertension identifies a patient who requires surgery; this includes an open surgical procedure or a balloon angioplasty.

There have been a number of different procedures performed for coarctation of the aorta, including subclavian flap, resection and end‐to‐end anastomosis enlarged to the aortic arch, resection and end‐to‐end anastomosis, patch aortoplasty, end‐to‐end conduit interposition, pyloroplasty‐type repair, left subclavian artery to descending thoracic aorta conduit interposition, and bypass using artificial graft material. 13 Which technique should be used depends on the surgical anatomy, but remains controversial. 14 Early complications include paraplegia and ischemic bowel.

In one series of 274 patients with isolated coarctation with or without a patent ductus arteriosus or bicuspid aortic valve, long‐term survival was best when operated on between 1 and 5 years of age (Figure 4). 15 In another series over a 25‐year period, the 30‐day postoperative mortality was 3.4% among 176 consecutive patients between 1 day and 33 years of age. 16 Ten‐year survival was 100% with simple coarctation (n=113), 92% with concomitant ventricular septal defect (n=27), and 67% with multiple congenital abnormalities (n=36). Residual or recurrent coarctation was 15.3%. Late hypertension was noted in 16.8% of 107 patients followed more than 5 years. The earlier the operation, the lower the probability of hypertension.

Figure 4.

Surgical survival probability stratified by age (N=252). Data derived from Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:541–547. 15

Balloon dilatation with or without endovascular stenting is increasingly performed as a less invasive alternative to open surgical repair; however, experience is less regarding long‐term outcomes. Endovascular stents are generally well tolerated. Studies have shown excellent results in both short‐term and immediate follow‐up. 17 Also, some stents can be further dilated up to 3 years after implantation to accommodate somatic growth. Criticisms of the use of the procedure include femoral vessel obstruction, long‐term durability, and aortic aneurysm formation at the coarctation site. There is less controversy in its use for recoarctation after surgical repair. In a retrospective analysis of 67 neonates, infants, and children undergoing balloon angioplasty for native coarctation, 25% developed recoarctation (peak gradient >20 mm Hg), 5% experienced an aneurysm, and 14% developed a partial or complete femoral artery occlusion after a 5‐ to 9‐year follow‐up. 18 Also, after median follow‐up of 5 years, 23% were hypertensive.

LATE SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

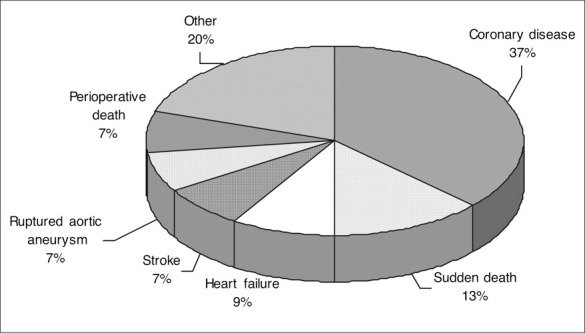

Late complications include recoarctation, hypertension, aortic aneurysm formation and rupture, sudden death, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and cerebrovascular accidents. Among 571 patients studied by Cohen et al. 19 with isolated coarctation, there were 87 late deaths. The causes are displayed in Figure 5. Age, gender, and postoperative systolic blood pressure were predictors of death. Coronary artery disease was the most common cause of death, which has been observed in other studies. 9 , 15 , 20

Figure 5.

Causes of death (n=87) among 571 survivors of coarctation repair Data derived from Circulation. 1989;80:840–845. 19

HYPERTENSION

Hypertension occurs with many patients with coarctation. However, the explanation of the increase in blood pressure is debated. The three theories are mechanical (obstruction increasing arterial resistance), neural (obstruction resetting carotid baroreceptors), and renal (ischemia to the kidneys). Paradoxical hypertension following surgical repair, but not after balloon angioplasty, may occur within 1 week of surgery, and is believed to be secondary to disruption of sympathetic fibers. 3

Reports of late hypertension are highly variable among patients following coarctation repair (8.3%–78%). 9 , 13 , 20 , 21 Hypertension occurred in 25% in the largest cohort, developing in those patients operated on after 9 years of age. 19 Studies have recommended the optimal timing to avoid late hypertension and recoarctation is 1.5 years. 9 Because the prevalence of hypertension increases with age, it is difficult to determine whether or not the occurrence of elevated blood pressure was secondary to restenosis.

Exercise‐induced hypertension occurs in 25%–56% of normotensive persons, and vascular dysfunction characterized by diminished brachial dilatation to nitroglycerin, increased pulse wave velocity, and reduced compliance have been reported after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. 21 , 22 , 23

SUMMARY

Coarctation of the aorta, a secondary cause of hypertension, requires careful attention to physical findings to make a diagnosis. The poor outcome of the natural history of coarctation is improved with surgical repair, but is not normal. 24 Hypertension may not abate and vigilance is required because of the frequent occurrence of late complications.

References

- 1. Perloff JK. The Clinical Recognition of Congenital Heart Disease. Philadelphia , PA : W.B. Saunders; 2003:113–143. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ayers CR, Slaughter AR, Smallwood HD, et al. Standards for quality care of hypertensive patients in office and hospital practice. Am J Cardiol. 1973;32:533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rocchini AP. Coarctation of the aorta. In: Izzo JL, Black HR, eds. Hypertension Primer. Dallas , TX : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:154–156. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katira R, Rathore VS, Lip GY, et al. Coarctation of aorta. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:537–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Therrien J, Webb G. Clinical update on adults with congenital heart disease. Lancet. 2003;362:1305–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazzanti L, Cacciari E. Congenital heart disease in patients with Turner's syndrome. Italian Study Group for Turner Syndrome (ISGTS) . J Pediatr. 1998;133:688–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Digilio MC, Marino B, Picchio F, et al. Noonan syndrome and aortic coarctation. Am J Med Genet. 1998;80:160–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Campbell M. Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. Br Heart J. 1970;32:633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brouwer RMHJ, Erasmus ME, Ebels T, et al. Influence of age on survival, late hypertension, and recoarctation in elective aortic coarctation repair. Including long‐term results after elective aortic coarctation repair with a follow‐up from 25 to 44 years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:525–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frank MJ, Alvarez‐Mena SC, Abdulla AM. Cardiovascular Physical Diagnosis. Chicago , IL : Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc; 1983:304. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mendelsohn AM, Banerjee A, Donnelly LF, et al. Is echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging superior for precoarctation angioplasty evaluation? Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;42:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corno AF, Botta U, Hurni M, et al. Surgery for aortic coarctation: a 30 years experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:1202–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanley FL. The various therapeutic approaches to aortic coarctation: is it fair to compare? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:471–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toro‐Salazar OH, Steinberger J, Thomas W, et al. Longterm follow‐up of patients after coarctation of the aorta repair. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seirafi PA, Warner KG, Geggel RL, et al. Repair of coarctation of the aorta during infancy minimizes the risk of late hypertension. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Suárez Lezo J, Pan M, Romero M, et al. Immediate and follow‐up findings after stent treatment for severe coarctation of aorta. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rao PS, Galal O, Smith PA, et al. Five‐ to nine‐year follow‐up results of balloon angioplasty of native aortic coarctation in infants and children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen M, Fuster V, Steele PM, et al. Coarctation of the aorta. Long‐term follow‐up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction. Circulation. 1989;80:840–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clarkson PM, Nicholson MR, Barratt‐Boyes BG, et al. Results after repair of coarctation of the aorta beyond infancy: a 10 to 28 year follow‐up with particular reference to late systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1481–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaemmerer H, Oelert F, Bahlmann J, et al. Arterial hypertension in adults after surgical treatment of aortic coarctation. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;46:121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Divitiis M, Pilla C, Kattenhorn M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure, left ventricular mass, and conduit artery function late after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:2259–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Divitiis M, Pilla C, Kattenhorn M, et al. Vascular dysfunction after repair of coarctation of the aorta: impact of early surgery. Circulation. 2001;104:I165–I170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bobby JJ, Emami JM, Farmer RD, et al. Operative survival and 40 year follow up of surgical repair of aortic coarctation. Br Heart J. 1991;65:271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]