Abstract

Chelation therapy is recognized as a safe and effective treatment option in patients with beta-thalassemia with iron overload. We report an 18-year-old male with acute abdomen and gastrointestinal bleeding with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection secondary to gastric perforation due to chelation therapy. This patient had a prolonged intensive care stay with complications of SARS-CoV-2 and a small bowel obstruction post-surgery that resolved after conservative management. Given the acute presentation, chelation therapy use and concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection, clinicians should keep an open mind on the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in patients with beta-thalassemia.

Keywords: Gastric perforation, Anti-chelation therapy, SARS-CoV-2, Thalassemia

Introduction

Beta-thalassemia is an autosomal recessive disorder of the blood, characterized by abnormal synthesis of beta chains of hemoglobin leading to different thalassemia phenotypes (thalassemia major, intermedia and minor) resulting in hemolytic anemia. With approximately 1 in 10,000 affected in Europe it can present in a variety of ways including individuals being asymptomatic to severe anemia requiring regular blood transfusions [1].

Gastric perforation is a life-threatening condition most commonly due to peptic ulcer disease post-Helicobacter pylori infection, hypersecretory states (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) trauma, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory intake, corticosteroids and malignancy.

In this article, we describe a case of an 18-year-old male who has known beta-thalassemia major who presented with gastric perforation secondary to chelation therapy and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Case Report

An 18-year-old male with known beta-thalassemia major on chelation therapy presented to a district general hospital with a 3-day history of generalised abdominal pain. He received weekly blood transfusions from a young age and had been taking deferasirox for over 5 years. He denied any melena or hematemesis. He denied taking any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroid use. He denied any alcohol consumption, smoking or recreational drugs.

On admission, his temperature was 34.6 °C, blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg and heart rate 160 beats per minute. Electrocardiogram confirmed a supra-ventricular tachycardia. On examination, he had bilateral clear lung fields with a tender and distended abdomen. He appeared clammy, pale and peripherally shutdown. His blood panel is shown in Table 1. His viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 1. Bloods on Admissions.

| Blood | Result | Normal |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 89 | 130 - 180 g/L |

| White cell count | 4.6 | 4 - 11 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 49 | 140 - 400 × 109/L |

| C-reactive protein | 9 | 0 - 9 mg/L |

| pH | 7.16 | 7.35 - 7.45 |

| PCO2 | 5.02 | 4.67 - 6.4 kPa |

| PO2 (on 24%) | 11.1 | 11.1 - 14.4 kPa |

| HCO3 | 12.7 | 22 - 26 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 6.9 | 0.5 - 1.6 mmol/L |

| Bilirubin | 49 | 0 - 20 µmol/L |

| ALT | 56 | 1 - 45 U/L |

| ALP | 190 | 30 - 130 U/L |

| Albumin | 37 | 35 - 50 g/L |

| Ferritin | 945 | 11 - 336 µg/L |

| Vitamin B12 | < 85 | 187 - 883 ng/L |

| Viral screen including hepatitis B/C and HIV | Negative |

PCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PO2: partial pressure of oxygen; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

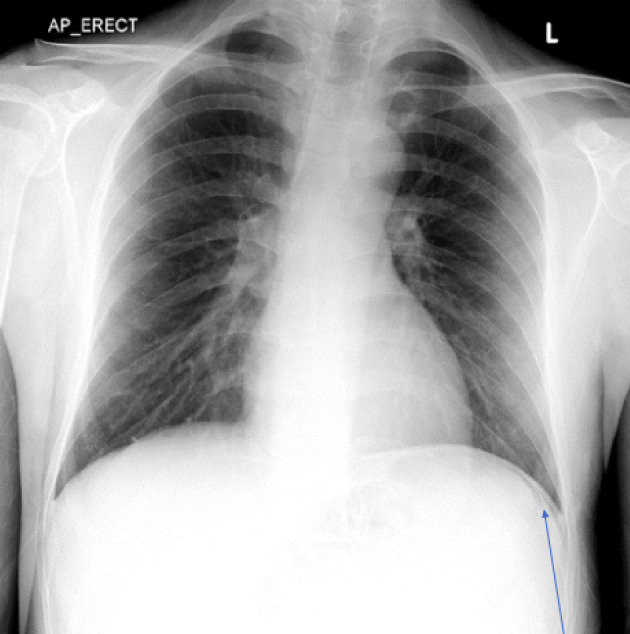

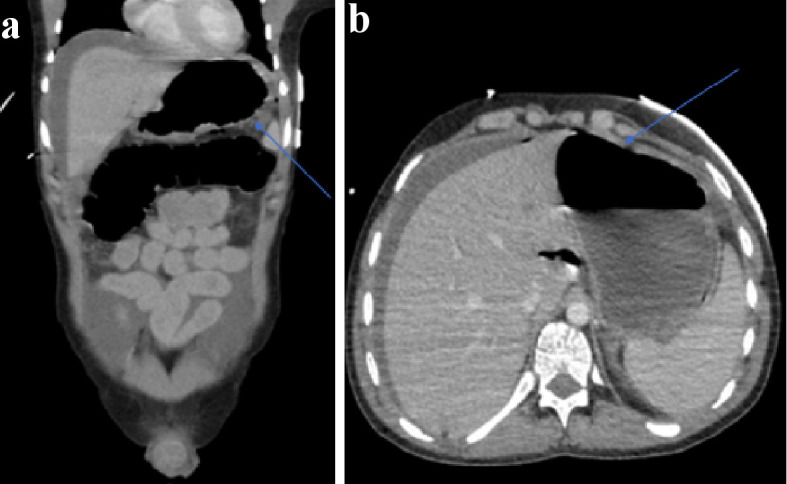

His initial management included aggressive fluid resuscitation, five units of packed red blood cells, a platelet pool, fresh frozen plasma, intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam, tranexamic acid and intravenous fluids. He was cardioverted with adenosine and synchronized direct-current cardioversion (DCCV) with 180 J. Despite this, he remained hemodynamically compromised and his hemoglobin dropped to 56. His admission chest radiograph identified air under the left hemidiaphragm (Fig. 1). He was intubated and ventilated and transferred for a computed tomography (CT) scan. This confirmed pneumoperitoneum with a moderate degree of ascites with a likely perforated gastric ulcer (Fig. 2). He was taken to theatre for urgent laparotomy where a perforated gastric ulcer was confirmed and treated surgically with omental patching. Biopsy samples demonstrated ulceration with a negative Campylobacter-like organism (CLO) test.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph depicting free air under the diaphragm shown by blue arrow pointing to free air.

Figure 2.

(a) Abdominal CT (axial views) with blue arrow indicating free air and perforation. (b) Abdominal CT (coronal views) depicting free air and fluid secondary to gastric perforation. CT: computed tomography.

During his intensive treatment unit (ITU) admission, he developed respiratory distress and increasing hypoxia. A repeat CT scan confirmed bilateral lung infiltrates in keeping with worsening SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and possible aspiration pneumonia. It was noted he had increased hepatosplenomegaly in keeping with recent hemolysis. He was also identified to have a deep vein thrombosis. He was treated with a 10-day course of antibiotics, remdesivir, dexamethasone and anticoagulation.

Discussion

Presentation to hospital with abdominal pain is quiet common with patients with beta-thalassemia, often associated with a wide range of etiologies including pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, portal vein thrombosis and kidney stones. However, correctly identifying the cause of abdominal pain in beta-thalassemia can be a challenge, as pain can be originating from the abdomen or referred from extra abdominal, metabolic or neurogenic causes [2].

One of the major problems associated with beta-thalassemia is developing iron overload due to regular blood transfusions and ineffective erythropoiesis. Iron overload is associated with increased morbidity and mortality as the body can only excrete 1 - 2 mg of iron per day (with one blood transfusion containing approximately 250 mg of iron) [3]. Randomized control trials have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of iron chelation therapy in treating iron overload in patients with beta-thalassemia [4, 5]. However, cases have been reported of gastric ulcer development and bowel perforation in the long-term use of deferasirox in children [6, 7]. To our knowledge this is the first case of gastrointestinal perforation due to chelation therapy in otherwise well adults; prior cases have been in the context of liver cirrhosis and secondary hemochromatosis [8]. Furthermore, iron overload itself can result in corrosive effect on the gastrointestinal system given its caustic properties [9].

Interestingly, our case included two significant factors contributing to gastric perforation that clinicians should keep in mind: the first risk factor being long-term deferasirox therapy, and the second being concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studies demonstrate deferasirox causes acute mitochondrial swelling, ultimately leading to organ toxicity and inflammation. It is well documented that mitochondrial swelling occurs in various critical diseases such as ischemic-perfusion injury, thus the use of deferasirox may have further contributed to bowel inflammation and perforation [10].

The gastrointestinal tract has an abundance of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors, where the virus utilizes it as a key binding site to gain access to host cells for further infection [11]. A meta-analysis demonstrated a correlation between the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms and severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. Cases have been reported of patients developing bowel perforation and esophageal erosions due to rapid replication of SARS-CoV-2 in the gastrointestinal epithelium, confirmed by biopsy and virology analysis of the affected epithelium [13, 14].

In the absence of any obvious cause to this gentleman’s perforation, it is likely that the long-term use of deferasirox combined with the acute severe inflammation due to SARS-CoV-2 resulted in gastric perforation. The mechanisms that may underpin this remain unclear but it is possible that there is a detrimental synergistic effect on the gastrointestinal tract that makes perforation more likely. Significantly, we are unable to confirm that the perforation was caused by either the deferasirox or by SARS-CoV-2, but in this case they remain as plausible factors that contributed to this pathology. We therefore believe, in light of the current pandemic, particular caution of patients on chelation therapy presenting with abdominal pain should be taken, to exclude gastrointestinal perforation.

On discharge a multidisciplinary discussion with hematology agreed that the overall benefit would be to continue deferasirox given the risk of iron overload and the complications. The patient was referred for novel gene therapy as a potential cure of his thalassemia.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic conditions are more vulnerable and at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Whilst rare, we describe a case of an 18-year-old male with beta-thalassemia presenting with gastric perforation secondary to chelation therapy and concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection. The current pandemic presents a unique challenge to clinicians. However, clinicians should keep in mind gastrointestinal symptoms and possible bowel perforation related to chelation therapy in patients with beta-thalassemia presenting with an acute abdomen, particularly during the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Full informed consent was obtained from patient.

Author Contributions

DC, YK conceptualized the manuscript. DC, YK and JPS conducted the literature review. NP and LK reviewed the manuscript, provided critical revisions. All authors agreed to the final version.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Galanello R, Origa R. Beta-thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Eleftheriou A. et al. Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Thalassaemia [Internet]. 2nd Revised edition. Nicosia (CY): Thalassaemia International Federation; 2008. Chapter 18, Outline of Diagnostic Dilemmas in Thalassaemia. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK173977/ [PubMed]

- 3.Cappellini MD. Exjade(R) (deferasirox, ICL670) in the treatment of chronic iron overload associated with blood transfusion. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(2):291–299. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennell DJ, Porter JB, Piga A, Lai Y, El-Beshlawy A, Belhoul KM, Elalfy M. et al. A 1-year randomized controlled trial of deferasirox vs deferoxamine for myocardial iron removal in beta-thalassemia major (CORDELIA) Blood. 2014;123(10):1447–1454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taher A, El-Beshlawy A, Elalfy MS, Al Zir K, Daar S, Habr D, Kriemler-Krahn U. et al. Efficacy and safety of deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, in heavily iron-overloaded patients with beta-thalassaemia: the ESCALATOR study. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82(6):458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauters T, Mondelaers V, Robays H, Hunninck K, de Moerloose B. Gastric ulcer in a child treated with deferasirox. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(2):112–113. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav SK, Gupta V, El Kohly A, Al Fadhli W. Perforated duodenal ulcer: a rare complication of deferasirox in children. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45(3):293–294. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.111901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadri A, Eskazan T, Salihoglu A, Hatemi I. Fatal gastrointestinal bleeding and perforated duodenal ulcer: a rare complication of deferasirox in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Biomedical Research. 2018;28(12):5620–5622. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin KJ, Muegge J, Saltzman DA, Acton RD, Hess DJ. Bowel perforation secondary to local tissue injury from intentional iron overdose. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2019;50:101301. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2019.101301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottwald EM, Schuh CD, Drucker P, Haenni D, Pearson A, Ghazi S, Bugarski M. et al. The iron chelator Deferasirox causes severe mitochondrial swelling without depolarization due to a specific effect on inner membrane permeability. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1577. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C. et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SH, Lui RN, Sung JJ. COVID-19 and the digestive system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(5):744–748. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao D, Yao F, Wang L, Zheng L, Gao Y, Ye J, Guo F. et al. A comparative study on the clinical features of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia with other pneumonias. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):756–761. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry BM, de Oliveira MHS, Benoit J, Lippi G. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(5):857–859. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02329-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.