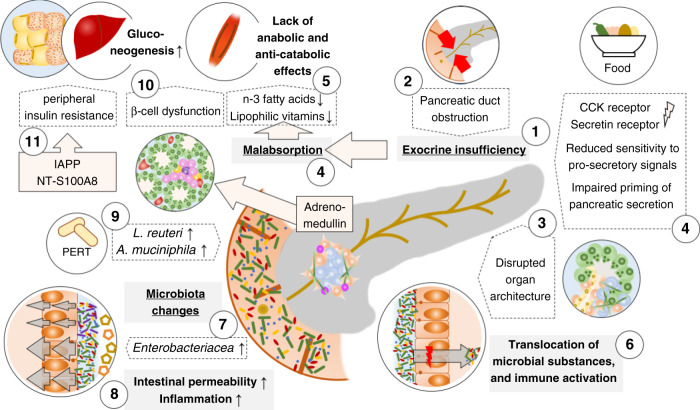

Fig. 3. Impaired pancreatic exocrine and endocrine function interact with alterations in the digestive tract to promote pancreatic cancer cachexia.

Pancreatic cancer induces pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) (1) through obstruction of the pancreatic duct (2) or disruption of the organ architecture (3) as well as an altered physiological function, i.e. a reduced sensitivity to the pro-secretory signals secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK) resulting in an impaired priming of the pancreatic (4). PEI results in malabsorption of nutrients including lipophilic vitamins and n-3 fatty acids which results in insufficient caloric uptake and a lack of anabolic or anti-catabolic signals (5). PEI, in combination with changes of the histological architecture of the pancreas, also leads to excess bacterial growth in the duodenum and the translocation of bacteria and bacterial components into the tumour with implications for the immune tone (6). Pancreatic cancer is associated with specific changes of the gut microbiota and outgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae (7), particularly Klebsiella, is associated with increased intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation linked to the development of cachexia (8). Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) counteracts cancer-related dysbiosis and promotes the abundance of Lactobacillus reuteri and Akkermansia muciniphila which potentially reduce muscle wasting and increase the anti-tumoural immune response, respectively (9). Changes of the endocrine function of the pancreas comprise tumour-derived local adrenomedullin that reduces the Insulin secretion from islet cells in the pancreas (10) and an increase of peripheral insulin resistance through pancreatic-cancer-induced secretion of the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) from β-cells and likely an increase of the S-100A8 N-terminal peptide (11). Endocrine dysregulation is also associated with increased gluconeogenesis (12), which depletes peripheral tissues to maintain the altered glucose utilisation.