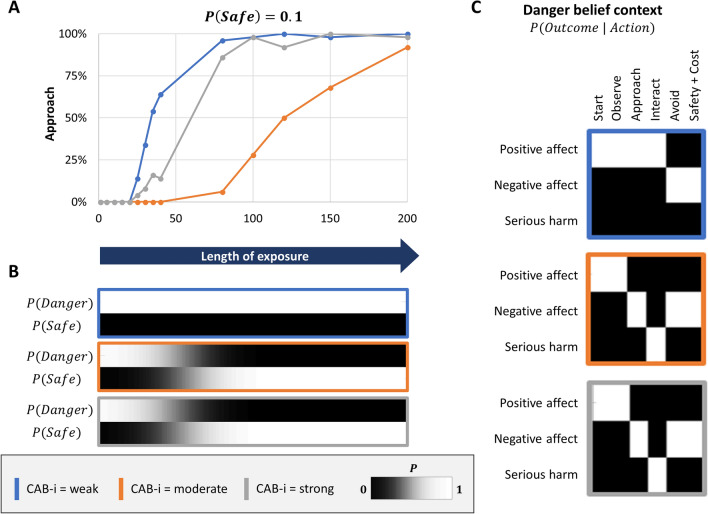

Figure 4.

Exposure therapy under strong explicit danger beliefs (i.e., as in the absence of cognitive restructuring; ) and different CAB interaction strengths. Approach behavior increased with length of exposure (panel A), but the underlying mechanisms differed depending on CAB interaction strengths. When CAB interactions were moderate (CAB-i = .5, orange outline) or strong (CAB-i = .9, grey outline), behavior change was the result of updates in explicit beliefs (panel B)—leaving implicit beliefs (panel C) unchanged and creating a vulnerability to the re-emergence of negative affect and avoidance responses in other contexts. Under weak CAB interactions (CAB-i = .1, blue outline), explicit danger beliefs remained unchanged (e.g., the simulated patient continued to have the automatic thought “this spider is dangerous”; panel B), but implicit beliefs (panel C) slowly adjusted such that avoidant affective responses attenuated over time—and were independent of changes in explicit beliefs. Learning was slower under moderate CAB interactions (.5, orange outline; panel A). As discussed in the main text, this is because the formal matrix structure in this case can also be interpreted as the patient being unsure that a safe context is possible (i.e., the hidden state for the possibility of another context started out making completely uninformative predictions)—thus, the patient needed to first infer the presence of a meaningfully distinct context. CAB-i = parameter encoding the efficacy of cognition-affect-behavior interactions; Safety + Cost = reaching safety along with opportunity costs that promote negative affect.