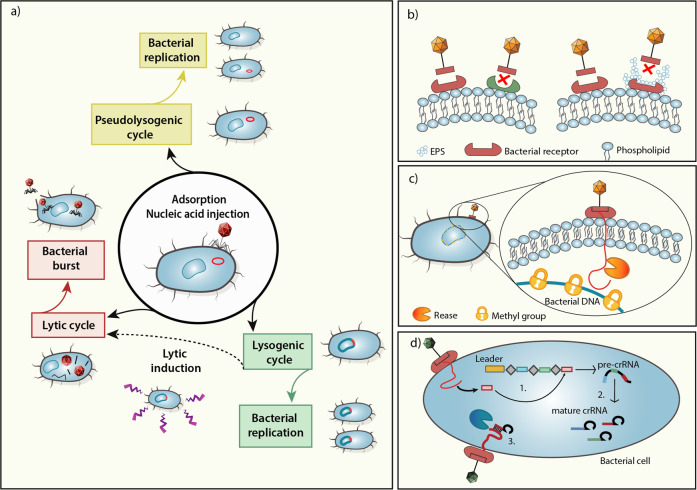

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of phage–bacterial interactions. a Following adsorption and injection of a phage genome into a bacterial host, phages can undergo a lytic cycle, leading to viral replication and bacterial cell lysis. Alternatively, in the lysogenic cycle, the phage genome is integrated as a prophage into the bacterial genome, until lytic induction triggered by a stress signal. Pseudolysogeny is the stable persistence of viral DNA in the host when growth conditions become unfavorable, and the phage is not replicating; thus, it will be inherited only by a single progeny cell. Innate bacterial phage evasion mechanisms include (b) the generation of mutated phage receptors or receptor masking by extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), and (c) cleavage of the phage genome following its injection into the bacterial cell, while methylated bacterial DNA remains protected. The adaptive bacterial antiphage machinery is exemplified by (d) the CRISPR-Cas system, which has several phases: 1. Acquisition: a short viral DNA portion (red rectangle) is inserted between palindromic sequences (gray rhombuses) to form a CRISPR array. 2. Expression: The CRISPR array is transcribed into a pre-crRNA that is then cleaved into mature crRNA ready for recognition. 3. Interference: the endonuclease recognizes and cleaves the complex crRNA-phage nucleic acid