Abstract

Glycopolymers have attracted increased attention as functional polymeric materials, and simple methods for synthesizing glycopolymers remain needed. This paper reports the aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic synthesis of four types of glycopolymers via two reactions: the β-galactosidase-catalyzed glycomonomer synthesis using 4,6-dimetoxy triazinyl β-D-galactopyranoside and hydroxy group-containing (meth)acrylamide and (meth)acrylate derivatives as the activated glycosyl donor substrate and as the glycomonomer precursors, respectively, followed by radical copolymerization of the resulting glycomonomer and excess glycomonomer precursor without isolating the glycomonomers. The resulting glycopolymers bearing galactose moieties exhibited specific and strong interactions with the lectin peanut agglutinin as glycoclusters.

Keywords: enzymatic glycosylation, β-galactosidase, glycomonomer, radical polymerization, glycocluster, glycopolymer

Abbreviations

p NP, p -nitrophenyl; DMT-glycoside, 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl glycoside; DMT-MM, 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride; Gal, galactose; p NP-Gal, p -nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside; DMT-Gal, 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl β-D-galactopyranoside; MeCN, acetonitrile; VA-044, 2,2'-azobis[2-(2-imidazolin-2-yl)propane]dihydrochloride; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PNA, peanut agglutinin; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

INTRODUCTION

Enzymes have recently attracted increased attention as sources of green catalysts. 1),2)Glycosidases catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds and are classified as either retaining or inverting enzymes. 3)Retaining glycosidases, which keep the anomeric αβ configuration of hydrolyzed saccharide products, can catalyze the glycosylation reaction and form a new glycosidic bond. Therefore, glycosylations catalyzed by retaining glycosidases are widely used in the synthesis of various oligosaccharides and glycosyl derivatives because the enzymes are stable and easily handled. 4),5),6)In principle, efficient glycosidase-catalyzed glycosylations require activated glycosyl donor substrates such as p -nitrophenyl ( p NP) glycosides 7),8)and glycosyl fluorides, 9),10),11)which have a leaving group at the anomeric position on a saccharide and are synthesized from corresponding unprotected saccharides through multistep processes those include the protection and deprotection of hydroxy groups on the saccharides. We have reported the direct synthesis of novel activated glycosyl donor substrates, 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl glycosides (DMT-glycosides), for glycosidase-catalyzed glycosylation. 12),13),14),15),16),17),18)DMT-glycosides can be directly synthesized in water from corresponding unprotected saccharides without the protection of hydroxy groups using the water-soluble dehydrating condensation agent 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMT-MM) and are applicable to various glycosidase-catalyzed glycosylations.

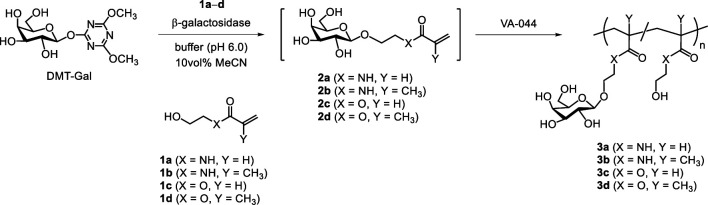

Glycopolymers consisting of a synthetic polymer backbone with pendant saccharide moieties are functional polymers and strongly and specifically interact with glycoreceptors such as lectins, viruses, and toxins owing to the formation of multivalent saccharide moieties around a polymer backbone. 19),20),21),22)This is known as the glycocluster effect. 23),24) Typical methods for synthesizing glycopolymers are classified into two categories: the polymerization of glycomonomers and post-polymerization modification caused by saccharide derivatives. Both methods generally require multistep chemical processes including the protection and deprotection of hydroxy groups on a saccharide for synthesizing glycomonomers and glycosyl derivatives. Several simple methods for synthesizing glycomonomers have been reported. Adharis et al. reported the enzymatic synthesis of (meth)acrylamide-based glycomonomers with a glucose moiety using p NP-β-D-glucopyranoside. 25) The p NP-glycoside was catalyzed using β-glucosidase in the presence of an ionic liquid to obtain the glycomonomers. Hoffmann et al. also reported β-galactosidase-catalyzed methacrylate-based glycomonomers with a galactose (Gal) moiety using p NP-β-D-galactopyranoside ( p NP-Gal) as the glycosyl donor substrate. 26) Tang et al. reported the one-pot chemical synthesis of acrylamide-based glycomonomers from unprotected saccharides using glycosyl amines. 27) These methods performed the final polymerization reaction using the isolated glycomonomers to obtain the glycopolymers. Little research has been conducted on the one-pot synthesis of glycopolymers using glycomonomers without isolating the glycomonomers. Therefore, simple methods for synthesizing glycopolymers remain needed. This study reports the aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers using DMT-glycoside as the activated glycosyl donor substrate for the glycosidase-catalyzed glycomonomer synthesis followed by radical polymerization without isolating the glycomonomers. The general one-pot chemoenzymatic procedure for synthesizing glycopolymers is presented in Fig. 1 . Four types of (meth)acrylamide- and (meth)acrylate-based glycomonomers with a Gal moiety 2a – d were enzymatically synthesized using 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl β-D-galactopyranoside (DMT-Gal) as the activated glycosyl donor substrate for the β-galactosidase-catalyzed glycosylation. Subsequently, four desired types of (meth) acrylamide- and (meth)acrylate-based glycopolymers 3a – d were synthesized by radical copolymerization through the enzymatic reaction without isolating the glycomonomers 2a – d .

Fig. 1. Aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers using DMT-Gal.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Enzymatic synthesis of glycomonomers.

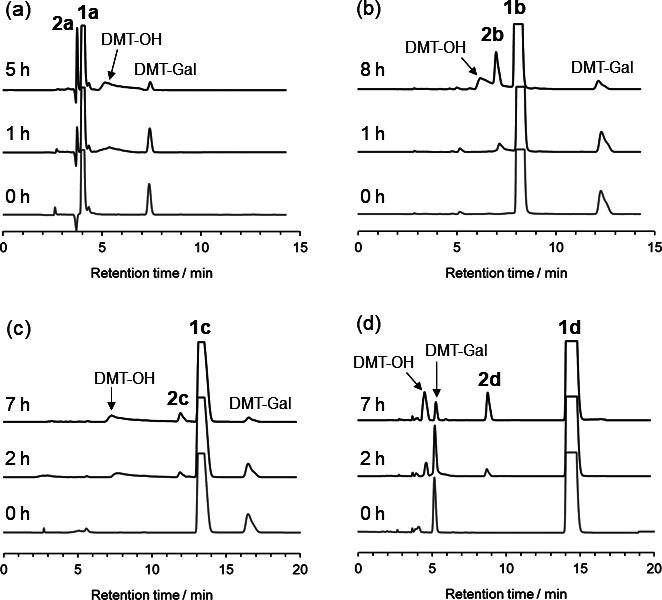

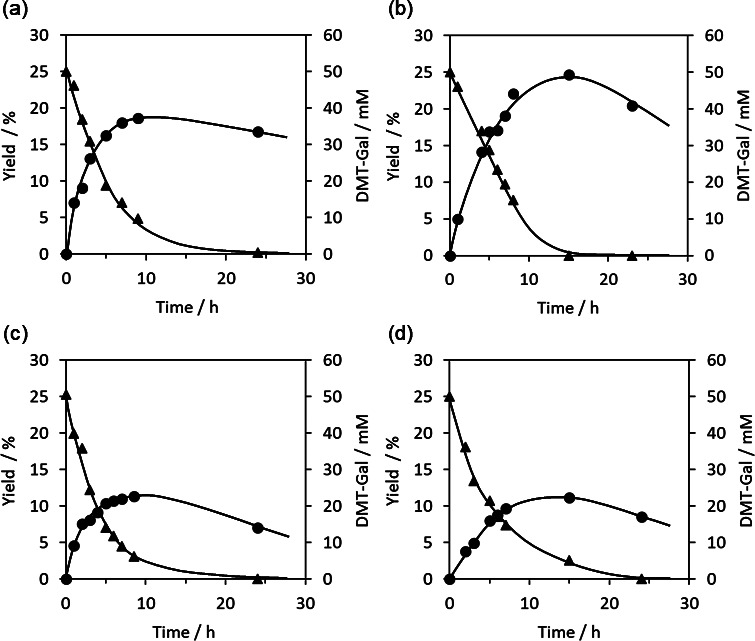

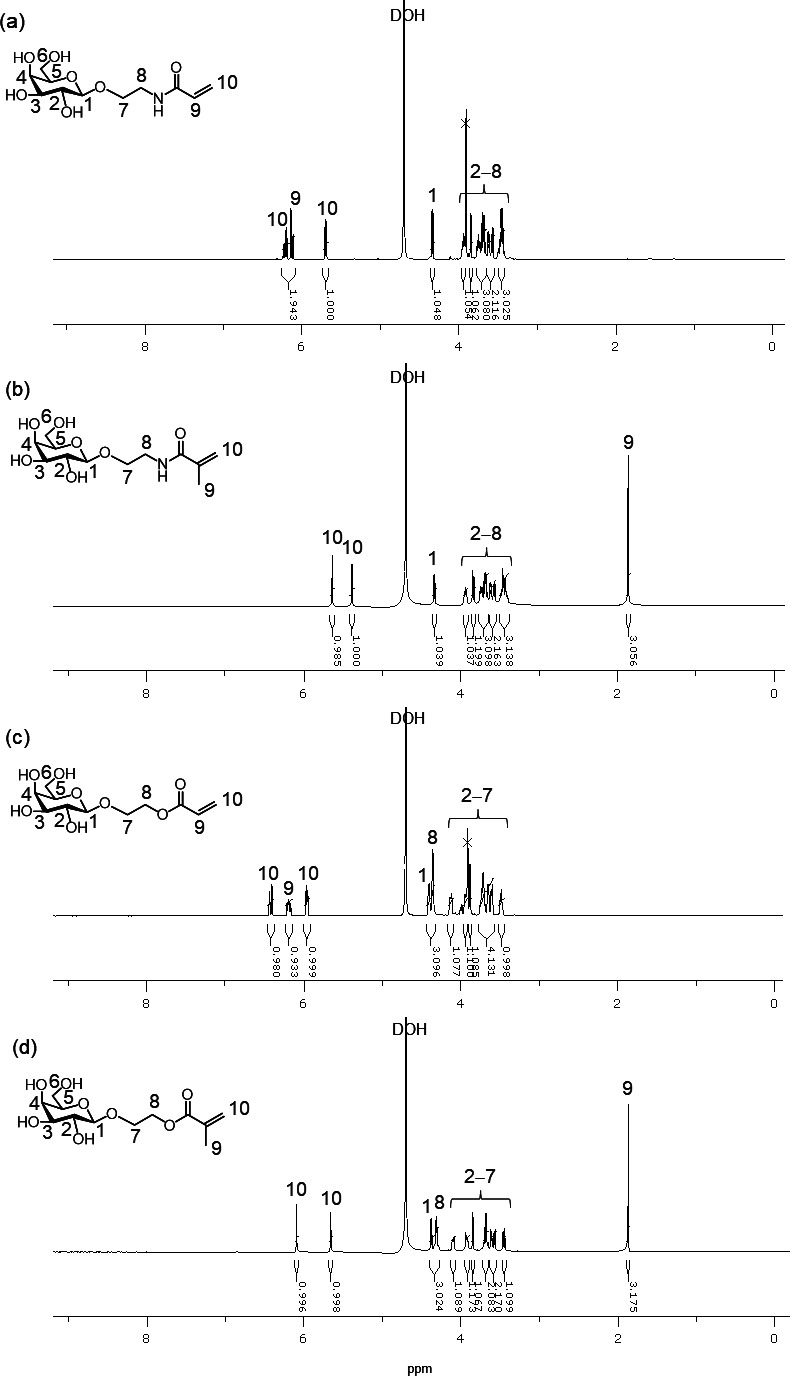

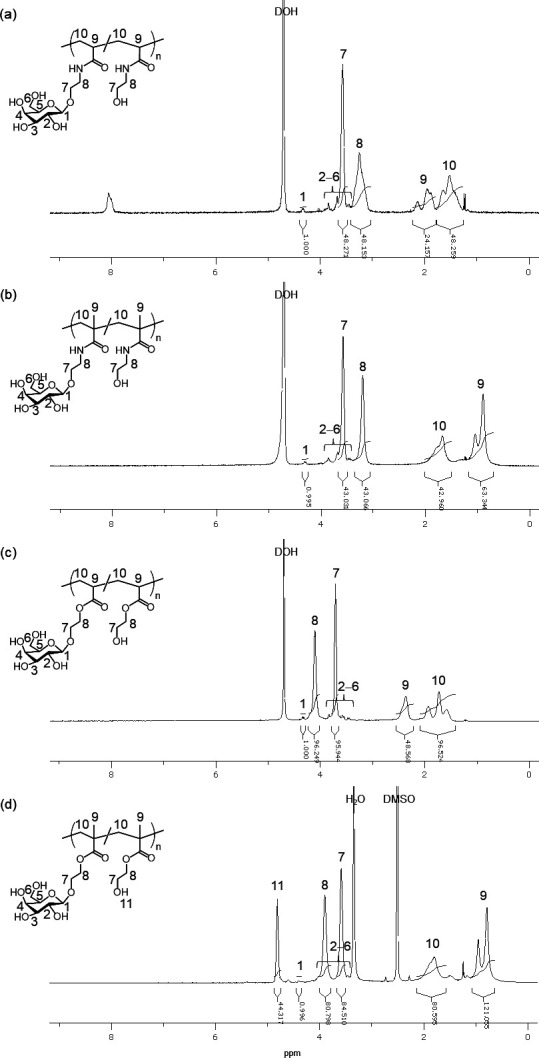

Enzymatic glycomonomer syntheses catalyzed using β-galactosidase and DMT-Gal, which was directly synthesized in water from unprotected Gal using DMT-MM (Fig. S1: See J.Appl. Glycosci. website), were conducted using four types of hydroxy group-containing glycomonomer precursors, (meth)acrylamide and (meth)acrylate derivatives 1a – d , to obtain the glycomonomers 2a – d . The enzymatic reactions were performed using the five equivalents of 1a – d in a phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 10 vol% acetonitrile (MeCN) at 30 °C. The resulting pH gap from the optimal pH of the β-galactosidase (pH 4.5) and the addition of MeCN increased glycosylation production using activated glycosyl donors and decreased the enzymatic hydrolysis of the products. 28) Based on HPLC analyses, the desired glycomonomers 2a – d were gradually produced as the DMT-Gal amount decreased ( Fig. 2 ). The triazine hydrolyzate (DMT-OH) released from DMT-Gal increased with decreasing DMT-Gal. The yield of 2a calculated from DMT-Gal reached the maximum of 19 % using the acrylamide-based precursor 1a ( Fig. 3a ). After the consumption of DMT-Gal, the glycomonomer product gradually decreased owing to enzymatic hydrolysis. When the enzymatic reactions were performed using the methacrylamide-based precursor 1b and (meth)acrylate-based precursors 1c and 1d , the yields of 2b – d reached the maximum of 25, 11, and 11 %, respectively ( Figs. 3b – d ). These results suggest that (meth)acrylamide derivatives 1a and 1b are suitable to acceptor substrates for the β-galactosidase-catalyzed glycomonomer synthesis compared with (meth)acrylate derivatives 1c and 1d . The product glycomonomers 2a – d were isolated by preparative HPLC and analyzed by NMR. The vinyl or vinylidene and Gal protons of 2a – d were detected in the 1 H NMR spectra at 6.4–5.4 and 4.3–3.4 ppm, respectively ( Fig. 4 ). The values of the coupling constant of anomeric protons at 4.3 ppm in 2a – d were 7.8 Hz, which indicated that the anomeric configuration of the obtained glycomonomers was a β-configuration. 13 C NMR spectra also showed the corresponding signals of 2a – d (Fig. S2: See J. Appl. Glycosci. website). Therefore, four types of glycomonomers, 2a – d , were successfully synthesized using DMT-Gal as the activated glycosyl donor substrate catalyzed by β-galactosidase with hydroxy group-containing (meth)acrylamide- and (meth)acrylate-based glycomonomer precursors 1a – d .

Fig. 2. HPLC chromatograms of the enzymatic reaction mixture for the synthesis of (a) 2a , (b) 2b , (c) 2c , and (d) 2d detected using UV rays at 214 nm and using 5, 4, 3, and 10 % MeCN-containing water as eluents, respectively.

Fig. 3. Time-courses of the yield and DMT-Gal concentration in the enzymatic reaction for the synthesis of (a) 2a , (b) 2b , (c) 2c , and (d) 2d . Circle (left vertical axis): yield of 2a – d . Triangle (right vertical axis): DMT-Gal concentration.

Fig. 4. 1 H NMR spectra of (a) 2a , (b) 2b , (c) 2c , and (d) 2d in D 2 O.

One-pot chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers using DMT-Gal.

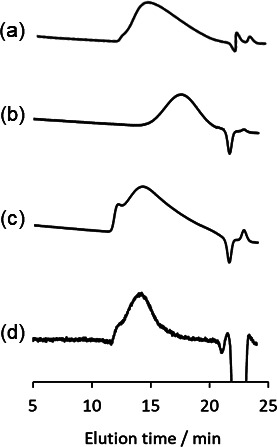

The aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers 3a – d using DMT-Gal was attempted via two reactions, namely, β-galactosidase-catalyzed glycomonomer synthesis using five equivalents of 1a – d for 16 h in a phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 10 vol% MeCN followed by radical copolymerization without isolating the glycomonomers 2a – d . After the above glycomonomer syntheses were catalyzed by β-galactosidase and enzymatic reaction mixture was heated for 5 min at 85 °C to deactivate the enzyme, the water-soluble radical initiator 2,2′-azobis[2-(2-imidazolin-2-yl)propane]dihydrochloride (VA-044) was added to the reaction mixture. The resulting mixture was kept under nitrogen bubbling before being sealed under vacuum and was then kept at 44 °C for 2–4 h to obtain the glycopolymers 3a – d as the copolymerization products of the glycomonomers 2a – d and excess 1a – d . The desired (meth)acrylamide- and (meth)acrylate-based glycopolymers 3a – d bearing Gal moieties were obtained after purification by dialysis. The polymer backbone and Gal protons of 3a – d were detected in the 1 H NMR spectra at 2.5–0.7 and 4.3–3.4 ppm, respectively ( Fig. 5 ). The (meth)acrylamide-based glycopolymers 3a and 3b were water-soluble, whereas, the (meth)acrylate-based glycopolymers 3c and 3d demonstrated low water solubility owing to their hydrophobic poly(meth)acrylate backbones. The GPC chromatograms showed the production of polymeric products ( Fig. 6 ). The properties of glycopolymers 3a – d obtained through the one-pot chemoenzymatic process are summarized in Table 1 . The total yield of 3a – d calculated from feeding DMT-Gal and 1a – d were moderate. The glycopolymers 3a – d constituted the 2.1–4.6 % Gal-containing unit ratio in the polymers, which roughly agreed with the yield of glycomonomers 2a – d and the feeding equivalences of 1a – d in the enzymatic reactions. These results indicate that four kinds of glycopolymers were successfully obtained by the one-pot process in moderate yields with good reproducibility. When the similar one-pot chemoenzymatic synthesis of the glycopolymer 3a was conducted via β-galactosidase-catalyzed glycomonomer 2a synthesis using p NP-Gal and the acrylamide-based precursor 1a under the same conditions used in the experiment with DMT-Gal, the conversion of the polymerization reaction without isolating the glycomonomer reached only 58 % in the similar yield of the glycomonomer 2a compared with the DMT-Gal experiment. This suggested that the p -nitrophenol released from p NP-Gal slows down the rate of radical polymerization because phenolic derivatives including p -nitrophenol are known as radical scavengers. 29) 30) Therefore, the chemoenzymatic protocol using DMT-glycoside as the activated glycosyl donor substrate for the glycosidase-catalyzed glycosylations without isolating glycomonomers achieved quantitative conversion of polymerization to obtain glycopolymers under a one-pot process and represents a simple process for synthesizing glycopolymers in aqueous media.

Fig. 5. 1 H NMR spectra of (a) 3a , (b) 3b , and (c) 3c in D 2 O, and (d) 3d in DMSO- d 6 .

Fig. 6. GPC chromatograms of (a) 3a , (b) 3b , and (c) 3c using the phosphate buffer as an eluent and (d) 3d using DMF as an eluent.

Table 1.

One-pot synthesis of glycopolymers using the enzymatic reaction mixture including glycomonomers.

| Glycopolymer | Polymerizationtime(h) | Conversion ofpolymerization a (%) | Yield b (%) | Mnc (g mol -1 ) | Mw / M n c | Gal unit ratio d (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 2 | 100 | 71 | 67900 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| 3b | 4 | 90 | 54 | 44600 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| 3c | 3 | 100 | 80 | 52800 | 7.1 | 2.1 |

| 3d | 3 | 100 | 66 | 175600 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

a Determined by 1 H NMR. b Total yield of glycopolymer calculated from DMT-Gal and 1a - d . c Determined by GPC. d Gal-containing unit ratio in glycopolymer determined by 1 H NMR.

Lectin binding test of glycopolymers.

Lectin binding tests of (meth)acrylamide-based glycopolymers 3a and 3b were conducted using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled proteins; peanut agglutinin (PNA), which can specifically bind to the β-Gal moiety; 31) 32) and bovine serum albumin (BSA). The (meth)acrylate-based glycopolymers 3c and 3d could not be applied in the lectin binding test owing to their low water solubility arising from their hydrophobic polymer backbones and the low degree of substitution of Gal moieties. The addition of FITC-labeled PNA to the glycopolymer solution decreased the fluorescence intensity as the glycopolymer was multivalently bound to PNA and consequently aggregated and precipitated ( Fig. 7 ). In contrast, a small change in the fluorescence intensity was observed when a FITC-labelled BSA was added to the glycopolymer solution. The fluorescence intensity was slightly affected by the addition of the same concentration of unprotected Gal as the concentration of the glycopolymer’s Gal moieties those are 8 and 9 μM of Gal. Moreover, the addition of both the glycopolymer and unprotected Gal to the FITC-labelled PNA solution similarly decreased the fluorescence intensity when only the glycopolymer was added to the FITC-labeled PNA solution. This suggests that the glycopolymers synthesized through the one-pot chemoenzymatic process using DMT-Gal specifically interacted with the corresponding lectin PNA due to the multivalency of their saccharide moieties.

Fig. 7. Lectin binding test of (a) 3a and (b) 3b .

c Unprotected Gal with the same concentration as the concentration of the glycopolymer’s Gal moieties ((a) 8 μM and (b) 9 μM).

CONCLUSIONS

Four types of (meth)acrylamide- and (meth)acrylate-based glycopolymers were successfully synthesized using DMT-glycoside via the aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic process of two reactions: the enzymatic synthesis of glycomonomers catalyzed by β-galactosidase using DMT-Gal and hydroxy group-containing (meth)acrylamide and (meth)acrylate derivatives as the activated glycosyl donor substrate and as the glycomonomer precursors, respectively, followed by radical copolymerization without isolating the resulting glycomonomers. This aqueous one-pot and chemoenzymatic process using DMT-glycoside proceeded without isolating the intermediate glycomonomers to obtain glycopolymers. Furthermore, the resulting (meth)acrylamide-based glycopolymers exhibited specific and strong interactions with the corresponding lectin as glycoclusters. This one-pot chemoenzymatic approach using DMT-glycosides represents a simple tool and can contribute to the reduction of reagents for synthesizing glycolpolymers. In addition, this one-pot process is applicable to not only monosaccharides but also di- and oligosaccharides because various DMT-glycosides can be directly synthesized from corresponding unprotected saccharides and used as activated glycosyl donor substrates for glycosidase-catalyzed glycosylations 12),13) 14) 15) 16) 17) 18) .

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials.

Gal and 2,6-lutidine were purchased from Nacalai Tesque, INC. (Kyoto, Japan). DMT-MM, p NP-Gal, and N -(2-hydroxyethyl)acrylamide ( 1a ) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). N -(2-Hydroxyethyl)methacrylamide ( 1b ), 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate ( 1c ), and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate ( 1d ) were purchased from Combi-Blocks Inc. (San Diego, USA), Nacalai Tesque, INC. and FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan), respectively. 1a and 1b were used after purification by activated alumina column. 1c and 1d were used after purification by washing using hexane and then through activated alumina column according to a literature. 33) The radical initiator VA-044 was purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. β-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae , FITC-labelled PNA from Arachis hypogaea , and FITC-labelled BSA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. (St. Louis, USA). All other reagents were commercially available and used without further purification.

Measurements.

The NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker BioSpin AV-300 and AV-600 spectrometers. The ESI-MS spectra were recorded using a Bruker Daltonics micrOTOF Q-III spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). The HPLC and GPC measurements were conducted using a system consisting of a JASCO PU-2089 pump and a JASCO CO-2065 column oven (JASCO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A JASCO UV-2075 ultraviolet detector and a JASCO RI-2031 refractive index detector were used for the HPLC and GPC analyses, respectively. A 5C18-MS-II column (ɸ4.6 × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, INC.) was used for the HPLC analysis. 5, 4, 3, and 10 % MeCN-containing water were used as the eluents at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30 °C to analyze the enzymatic reaction with 1a – d , respectively. A Shodex OHpak SB-804 HQ column (ɸ8.0 × 300 mm, Showa Denko K.K., Tokyo, Japan) was used for the GPC analysis of 3a – c using a phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min at 30 °C. Pullulan samples were used as standards. A Shodex KD-804 column (ɸ8.0 × 300 mm, Showa Denko K.K.) was used for the GPC analysis of 3d using N , N -dimethylformamide (DMF) containing 10 mM lithium bromide as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min at 50 °C. Poly(methylmethacrylate) samples were used as standards. The fluorescence intensity was recorded using a JASCO FP-6500 fluorometer for the lectin binding tests.

Synthesis of DMT-Gal.

Gal (900 mg, 5.0 mmol) was dissolved in water (20 mL) and the solution was kept overnight at room temperature to achieve an αβ-configuration equilibrium. DMT-MM (2.80 g, 10.0 mmol) and 2,6-lutidine (0.6 mL, 5.0 mmol) were then added to the solution, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After concentration of the reaction mixture under reduced pressure, the product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (ethyl acetate/methanol = 5/1) and recrystallized from methanol to yield DMT-Gal (639 mg, 2.0 mmol, 40.0 %).

1 H NMR (300 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 5.78 (1H, d, H1, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.97–3.94 (7H, m, OCH 3 and H4), 3.80 (1H, m, H5), 3.73 (1H, d, H2), 3.69 (1H, dd, H3), 3.66 (2H, d, H6). 13 C NMR (75 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 173.3 and 172.0 (triazine), 97.6 (C1), 76.1 (C5), 72.4 (C3), 69.7 (C2), 68.4 (C4), 60.7 (C6), 55.9 (OCH 3 ). ESI-MS: Found: m/z 342.063, Calcd. for C 11 H 17 N 3 NaO 8 ([M+Na] + ): m/z 342.091.

Enzymatic synthesis of glycomonomers using DMT-Gal.

A general procedure for the enzymatic reactions is described. A mixture of DMT-Gal (3.2 mg, 10 μmol), hydroxy group-containing glycomonomer precursor ( 1a – d , 50 μmol), and β-galactosidase (0.1 U) in 0.2 mL of a phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0) containing 10 vol% MeCN was incubated at 30 °C. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by HPLC and detected using UV rays at 214 nm. The products were isolated by preparative HPLC using a combined system of a JASCO PU-2086 pump, a JASCO CO-2065 column oven, and a JASCO UV-2075 UV detector (214 nm). A 5C18-MS-II column (ɸ20 × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque, INC.) was used and the eluent was introduced at a flow rate of 12.0 mL/min at 30 °C. The yields of 2a – d were calculated from DMT-Gal.

2a . 1 H NMR (600 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 6.22 (1H, dd, -CH=C H 2 ), 6.12 (1H, d, -C H =CH 2 ), 5.70 (1H, d, -CH=C H 2 ), 4.34 (1H, d, H1, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.94 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.85 (1H, d, H4), 3.75 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.69 (2H, m, H6), 3.62 (1H, m, H5), 3.57 (1H, dd, H3), 3.50-3.41 (3H, m, H2 and -O-CH 2 -C H 2 -N). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 168.7 (C=O), 129.9 (- C H=CH 2 ), 127.4 (-CH= C H 2 ), 103.0 (C1), 75.2 (C5), 72.7 (C3), 70.8 (C2), 68.6 (C4), 68.4 (-O- C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 61.0 (C6), 39.4 (-O-CH 2 - C H 2 -N). ESI-MS: Found: m/z 300.117, Calcd. for C 11 H 19 NNaO 7 ([M+Na] + ): m/z 300.106.

2b . 1 H NMR (600 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 5.64 (1H, s, -C(CH 3 )=C H 2 ), 5.38 (1H, s, -C(CH 3 )=C H 2 ), 4.33 (1H, d, H1, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.94 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.85 (1H, d, H4), 3.83 (1H, s, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.74 (2H, m, H6), 3.69 (1H, m, H5), 3.62 (1H, m, H3), 3.50-3.36 (3H, m, H2 and -O-CH 2 -C H 2 -N), 1.80 (3H, s, -C(C H 3 )=CH 2 ). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 172.2 (C=O), 139.1 (- C (CH 3 )=CH 2 ), 121.1 (-C(CH 3 )= C H 2 ), 103.1 (C1), 75.2 (C5), 72.7 (C3), 70.7 (C2), 68.6 (C4), 68.4 (O- C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 61.0 (C6), 39.5 (O-CH 2 - C H 2 -N), 17.6 (-C( C H 3 )=CH 2 ). ESI-MS: Found: m/z 314.158, Calcd. for C 12 H 21 NNaO 7 ([M+Na] + ): m/z 314.122.

2c . 1 H NMR (600 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 6.42 (1H, dd, -CH=C H 2 ), 6.19 (1H, d, -C H =CH 2 ), 5.96 (1H, d, -CH=C H 2 ), 4.41 (1H, d, H1, J = 7.8 Hz), 4.36 (2H, d, -O-CH 2 -C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 4.13 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 3.96 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 3.88 (1H, d, H4), 3.72 (2H, m, H6), 3.65 (1H, m, H5), 3.60 (1H, dd, H3), 3.48 (1H, t, H2). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 168.5 (C=O), 132.6 (- C H=CH 2 ), 127.5 (-CH= C H 2 ), 103.1 (C1), 75.2 (C5), 72.8 (C3), 70.7 (C2), 68.6 (C4), 67.8 (O- C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 64.2 (O-CH 2 - C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 60.9 (C6). ESI-MS: Found: m/z 301.079, Calcd. for C 11 H 18 NaO 8 ([M+Na] + ): m/z 301.090.

2d . 1 H NMR (600 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 6.10 (1H, s, -C(CH 3 )=C H 2 ), 5.66 (1H, s, -C(CH 3 )=C H 2 ), 4.38 (1H, d, H1, J = 7.8 Hz), 4.31 (2H, m, -O-CH 2 -C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 4.10 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 3.92 (1H, m, -O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 3.85 (1H, d, H4), 3.68 (2H, m, H6), 3.61 (1H, m, H5), 3.57 (1H, dd, H3), 3.45 (1H, t, H2), 1.85 (3H, s, -C(C H 3 )=CH 2 ). 13 C NMR (150 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 169.7 (C=O), 135.8 (- C (CH 3 )=CH 2 ), 127.0 (-C(CH 3 )= C H 2 ), 103.1 (C1), 75.2 (C5), 72.7 (C3), 70.7 (C2), 68.6 (C4), 67.9 (O- C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 64.4 (O-CH 2 - C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 60.9 (C6), 17.4 (-C( C H 3 )=CH 2 ). ESI-MS: Found: m/z 315.135, Calcd. for C 12 H 20 NaO 8 ([M+Na] + ): m/z 315.106.

One-pot chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers using DMT-Gal.

A general procedure for the one-pot synthesis of glycopolymers is described. DMT-Gal (6.4 mg, 20 μmol), hydroxy group-containing glycomonomer precursor ( 1a – d , 100 μmol), and β-galactosidase (0.2 U) were dissolved in 0.4 mL of a phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0) containing 10 vol% MeCN. The resulting mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 16 h. After heating the reaction mixture at 85 °C for 5 min, VA-044 (0.6 mg, 2 μmol) was added to the reaction mixture. The resulting mixture was kept under nitrogen bubbling for 15 min, sealed under vacuum, and was then kept at 44 °C for 2–4 h. The product polymers were purified by dialysis (Spectra/Por 7, MWCO 3500, Repligen Corporation, Waltham, MA,USA) against deionised water and freeze-dried to yield the glycopolymers. Total yields of glycopolymers 3a – d were calculated from feeding DMT-Gal and 1a – d .

3a.1 H NMR (300 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 8.1–8.0 (NH), 4.4–4.3 (H1), 3.9–3.4 (H2-6), 3.7–3.5 (-O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.4–3.1 (-O-CH 2 -C H 2 -N), 2.2–1.8 ((-CH 2 -C H -) n ), 1.8–1.3 ((-C H 2 -CH-) n ).

3b.1 H NMR (300 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 4.4–4.3 (H1), 3.9–3.4 (H2-6), 3.7–3.5 (-O-C H 2 -CH 2 -N), 3.3–3.1 (-O-CH 2 -C H 2 -N), 2.0–1.5 ((-C H 2 -C(CH 3 )-) n ), 1.2–0.8 ((-CH 2 -C(C H 3 )-) n ).

3c.1 H NMR (300 MHz, D 2 O): δ (ppm) 4.4–4.3 (H1), 4.2–4.0 (-O-CH 2 -C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 3.9–3.4 (H2–6), 3.8–3.6 (-O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 2.5–2.3 ((-CH 2 -C H -) n ), 2.0–1.5 ((-C H 2 -CH-) n ).

3d.1 H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO- d 6 ): δ (ppm) 4.9–4.8 (-O-CH 2 -CH 2 -O H ), 4.4 (H1), 4.0–3.8 (-O-CH 2 -C H 2 -O-C(=O)), 4.0–3.4 (H2–6), 3.7–3.5 (-O-C H 2 -CH 2 -O-C(=O)), 2.0–1.7 ((-C H 2 -C(CH 3 )-) n ), 1.0–0.7 ((-CH 2 -C(C H 3 )-) n ).

Lectin binding test.

A general procedure for the lectin binding test is described. The FITC-labelled protein, PNA or BSA, with a final concentration of 0.8 μM and the glycopolymer synthesized through the one-pot process using DMT-Gal with a final concentration of 10 μg/mL were mixed in 40 μL of PBS(+). The mixture was incubated in the dark at 30 °C for 16 h. After centrifugation, the fluorescence intensity of the supernatant was measured by a fluorometer (λ ex = 495 nm, λ em = 520 nm).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by a grant from the Shorai Foundation for Science and Technology. This work was the result of using research equipment shared in MEXT Project for promoting public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting introduction of the new sharing system) Grant Number JPMXS0421800220.

References

- 1).Whitesides G.M. and Wong C.-H.: Enzymes as catalysts in synthetic organic chemistry [New Synthetic Methods (53)]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 24, 617–638 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 2).Shoda S., Uyama H., Kadokawa J., Kimura S., and Kobayashi S.: Enzymes as Green Catalysts for Precision Macromolecular Synthesis. Chem. Rev., 116, 2307–2413 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Bojarová P. and Křen V.: Glycosidases: a key to tailored carbohydrates. Trend. Biotechnol., 27, 199–209 (2009)). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Davis B.G.: Recent developments in oligosaccharide synthesis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans., 1, 2137–2160 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 5).Shoda S.: Enzymatic Glycosylation. in Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Vol. II, pp. 1465–1496 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 6).Kobayashi S.: New developments of polysaccharide synthesis via enzymatic polymerization. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, 83, 215–247 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Nilsson K.G.I.: A simple strategy for changing the regioselectivity of glycosidase-catalysed formation of disaccharides. Carbohydr. Res., 167, 95–103 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Winum J.Y., Leydet A., Seman M., and Montero J.L.: Synthesis and biological activity of glycosyl conjugates of N -(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide. Farmaco, 56, 319–324 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Kobayashi S., Kashiwa K., Kawasaki T., and Shoda S.: Novel method for polysaccharide synthesis using an enzyme: the first in vitro synthesis of cellulose via a nonbiosynthetic path utilizing cellulase as catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 113, 3079–3084 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 10).Shoda S., Obata K., Karthaus O., and Kobayashi S.: Cellulase-catalysed, stereoselective synthesis of oligosaccharides. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 1402–1404 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 11).Shoda S., Fujita M., and Kobayashi S.: Glycanase-catalyzed synthesis of non-natural oligosaccharides. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol., 10, 279–289 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 12).Tanaka T., Noguchi M., Kobayashi A., and Shoda S.: A novel glycosyl donor for chemo-enzymatic oligosaccharide synthesis: 4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl glycoside. Chem. Commun., 2016–2018 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Tanaka T., Noguchi M., Watanabe K., Misawa T., Ishihara M., Kobayashi A., and Shoda S.: Novel dialkoxytriazine-type glycosyl donors for cellulase-catalysed lactosylation. Org. Biomol. Chem., 8, 5126–5132 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Kobayashi A., Tanaka T., Watanabe K., Ishihara M., Noguchi M., Okada H., Morikawa Y., and Shoda S.: 4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine oligoxyloglucans: Novel one-step preparable substrates for studying action of endo-β-1,4-glucanase III from Trichoderma reesei. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 20, 3588–3591 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Tanaka T., Noguchi M., Ishihara M., Kobayashi A., and Shoda S.: Synthesis of non-natural xyloglucans by polycondensation of 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl oligosaccharide monomers catalyzed by endo-β-1,4-glucanase. Macromol. Symp., 297, 200–209 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 16).Noguchi M., Nakamura M., Ohno A., Tanaka T., Kobayashi A., Ishihara M., Fujita M., Tsuchida A., Mizuno M., and Shoda S.: A dimethoxytriazine type glycosyl donor enables a facile chemo-enzymatic route toward α-linked N -acetylglucosaminyl-galactose disaccharide unit from gastric mucin. Chem. Commun., 5560–5562 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Tanaka T., Wada T., Noguchi M., Ishihara M., Kobayashi A., Ohnuma T., Fukamizo T., Brzezinski R., and Shoda S.: 4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl β-D-glycosaminides: novel substrates for transglycosylation reaction catalyzed by exo-β-D-glucosaminidase from Amycolatopsis orientalis. J. Carbohydr. Chem., 31, 634–646 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18).Ohnuma T., Tanaka T., Urasaki A., Dozen S., and Fukamizo T.: A novel method for chemo-enzymatic synthesis of chitin oligosaccharide catalyzed by the mutant of inverting family GH19 chitinase using 4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl α-chitobioside as a glycosyl donor. J. Biochem., 165, 497–503 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Narain R.: Engineered Carbohydrate-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications: Polymers, Surfaces, Dendrimers, Nanoparticles, and Hydrogels , John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20).Slavin S., Burns J., Haddleton D.M., and Becer C.R.: Synthesis of glycopolymers via click reactions. Eur. Polym. J., 47, 435–446 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21).Miura Y., Hoshino Y., and Seto H.: Glycopolymer Nanobiotechnology. Chem. Rev., 116, 1673–1692 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Pramudya I. and Chung H.: Recent progress of glycopolymer synthesis for biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci., 7, 4848–4872 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Mammen M., Choi S.K., and Whitesides G.M.: Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 37, 2755–2794 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Lundquist J.J. and Toone E.J.: The Cluster Glycoside Effect. Chem. Rev., 102, 555–578 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Adharis A., Vesper D., Koning N., and Loos K.: Synthesis of (meth)acrylamide-based glycomonomers using renewable resources and their polymerization in aqueous systems. Green Chem., 20, 476–484 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26).Hoffmann M., Gau E., Braun S., Pich A., and Elling L.: Enzymatic synthesis of 2-(β-Galactosyl)-ethyl methacrylate by β-galactosidase from Pyrococcus woesei and application for glycopolymer synthesis and lectin studies. Biomacromolecules, 21, 974–987 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Tang J., Ozhegov E., Liu Y., Wang D., Yao X., and Sun X.-L.: Straightforward synthesis of N -glycan polymers from free glycans via cyanoxyl free radical-mediated polymerization. ACS Macro Lett., 6, 107–111 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Tanaka T., Matsuura A., Aso Y., and Ohara H.: One-pot chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopolymers from unprotected sugars via glycosidase-catalysed glycosylation using triazinyl glycosides. Chem. Commun., 56, 10321–10324 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Bagdasaŕlan K.S. and Sinitsina Z.A.: Polymerization inhibition by aromatic compounds. J. Polym Sci. Part A: Gen. Pap., 52, 31–38 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 30).Caldwell R.G. and Ihrig J.L.: The Reactivity of Phenols toward Peroxy Radicals. I. Inhibition of the Oxidation and Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate by Phenols in the Presence of Air. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 84, 2878–2886 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 31).Fish W.W., Hamlin L.M., and Miller R.L.: The macromolecular properties of peanut agglutinin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 190, 693–698 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Neurohr K.J., Young N.M., and Mantsch H.H.: Determination of the carbohydrate-binding properties of peanut agglutinin by ultraviolet difference spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem., 255, 9205–9209 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Huang W., Kim J.-B., Bruening M.L., and Baker G.L.: Functionalization of surfaces by water-accelerated atom-transfer radical polymerization of hydroxyethyl methacrylate and subsequent derivatization. Macromolecules, 35, 1175–1179 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.