ABSTRACT

Aim:

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated much concern worldwide. Due to its high transmissibility, many young university students have had to carry out their academic activities in mandatory social isolation, which could generate excessive anxiety. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the anxiety levels in Peruvian dentistry students developed during COVID-19 mandatory social isolation.

Materials and Methods:

An analytical, observational, and transversal study was carried out in 403 dentistry students in the last two years from three Peruvian universities from May to July 2020. The Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale was used to detect anxiety symptoms and their respective diagnoses. A logit model was used to evaluate the association of the variables: age group (X1), gender (X2), type of university (X3), and marital status (X4), with the anxiety levels of the students, considering a p-value less than 0.05.

Results:

The prevalence of anxiety resulted in 56.8% (95% confidence interval (CI): 51.9–61.7) of 403 dentistry students. According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the type of university was the only variable that demonstrated to have a significant influence on the development of anxiety with an odds ratio (OR = 1.98; CI: 1.29–3.02); whereas the other variables such as age group (OR = 0.77; CI: 0.49–1.20), gender (OR = 1.15; CI: 0.72–1.84), and marital status (OR = 0.75; CI: 0.35–1.60) were not considered factors that influenced the development of anxiety.

Conclusion:

More than a half of the Peruvian dentistry students from three universities showed mild-to-severe anxiety levels. Students from a private university have a 98% higher chance of developing anxiety in comparison to students from public universities. Other variables such as gender, age group, or marital status were not considered influencing factors to develop anxiety.

KEYWORDS: Anxiety, COVID-19, odontology, Peru, social isolation, university students

INTRODUCTION

The new coronavirus, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), was originated in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. It spread rapidly throughout the world, causing an outbreak of severe acute infectious pneumonia.[1] Currently (October 2020), this new coronavirus has shown a fatality rate of 2.78% worldwide. Because of its highly contagious rates, the mandatory social isolation of citizens has been established in many affected countries.[2] This decision has brought about socioeconomic and psychological changes in the global population. These changes due to the pandemic crisis can significantly affect mental health. As days of isolation and restrictive measures increase, so do concerns, causing anxiety levels in people to rise.

Anxiety has been defined as a psychophysiological alarm response that arises when we need to react to certain situations or stimuli perceived as dangerous, which can end in an anxiety disorder. It is an excessive fear of certain triggering stimuli that manifest in different ways in people.[3,4,5] Therefore, different authors suggest to carry out more studies regarding the presence of anxiety in university students of health sciences. They also recommend to analyze its association with various sociodemographic factors, such as gender, age, type of university among others, since nowadays there is no consensus on which factors trigger anxiety in these young people.[6,7,8,9]

In contrast, as a consequence of the mandatory social isolation, in-person classes in Lima, Peru have been cancelled to start the distance learning modality at the national level.[10,11] This teaching mode requires the use of uncommon learning methods and the acquisition of new habits by students, which could significantly affect not only their academic performance but also their mental health.[12,13,14]

In a study conducted in April 2020 in 976 people from Spain, levels of anxiety, stress, and depression were measured using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21). It concluded that younger people had more symptoms of anxiety since the lockdown began in the first phase of the COVID-19 outbreak.[15]

In addition, a research in China used the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) to estimate the prevalence of anxiety in 512 medical workers during the COVID-19 outbreak, resulting in a prevalence of 12.5%.[16] Moreover, in February 2020, SAS was used to measure the anxiety levels of 1158 students from a Chinese university during the COVID-19 outbreak, and it was observed that the SAS average score was significantly higher than national standard. Therefore, it was concluded that Chinese university students developed more anxiety due to fear of COVID-19 as well as the beginning of a new mode of study.[17] Some research has shown that medical science students are the most likely to suffer from anxiety symptoms. According to the authors,[18,19,20,21,22] there are various sociodemographic factors that can increase worries, stress, and their anxiety levels.

In this context, in which university dentistry students carry out distance learning in Peru from March 2020 to the present (October 2020), it is of utmost importance and interest to know the anxiety levels of these students during mandatory social isolations. If high levels of anxiety are confirmed, preventive strategies could be developed to reduce this psychological impact during the period of lockdown. Thus, the objective of this research was to evaluate the anxiety levels developed in Peruvian dentistry students during the mandatory social isolation by COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BIOETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This research respected the bioethical principles for medical research involving human subjects of the Declaration of Helsinki[23] related to confidentiality, freedom, respect, and non-maleficence. This research was approved by the Committee of the Research Institute of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega University with the resolution 033-2020-RUIGV.

TYPE OF STUDY

An analytical, observational, prospective, and cross-sectional study was conducted.

POPULATION AND SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS

The initial population comprised 489 Peruvian dentistry students, from the fourth or fifth year of the professional major of Dentistry from May to July 2020. After considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 403 students remained as the final population, of whom 133 (33.00%) were from Federico Villareal National University (UNFV), 103 (25.56%) from Alas Peruanas University (UAP), and 167 (41.44%) from Inca Garcilaso de la Vega University (UIGV). Since the entire final population was included in the study, no sample size calculation was required.

Inclusion criteria

Students of both sexes of legal age;

Dentistry students;

Students enrolled in semester 2020-1;

Students who accepted virtual informed consent;

Dentistry students taking virtual classes during COVID-19 pandemic.

Exclusion criteria

Students who did not wish to participate in this study;

Students who discontinued the academic term.

ASSOCIATED FACTORS

The associated factors considered in this study related to the development of anxiety were gender, type of university, age group, and marital status.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INSTRUMENT

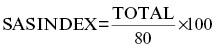

For the detection of anxiety symptoms, the validated Spanish version of the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) was used.[24,25,26] This questionnaire consisted of 20 items distributed in two dimensions. The first dimension consisted of five items that evaluated psychological or affective signs and symptoms. The second dimension consisted of 15 items that evaluated somatic signs and symptoms. All of the questions referred to the signs and symptoms that the students felt 15 days prior to the evaluation. Each item had four ordinal alternatives of reply (Likert-type scale): “never or rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “usually or all the time” with score from 1 to 4, respectively. When solving, the individual value of each information was recorded. The sum of this values resulted in a total, which became an “anxiety index” (SAS index) based on an equation[24]:

where SAS is the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.

The results of the anxiety level were divided into the following ranges:

Level 0: No anxiety (below 45),

Level 1: Mild to moderate anxiety (45–59),

Level 2: Severe anxiety (60–74),

Level 3: Most extreme anxiety (75 or more).

The instrument reproducibility test was evaluated in a sample of 30 students. The questionnaire was taken twice at two different times over a 10-day interval,[27] altering the order of questions and answers to avoid memory bias (test–retest). The results of the analysis of variance test indicated no bias since the averages between the two evaluations did not present a significant difference (p = 0.061). This resulted in an intraclass correlation coefficient greater than or equal to 0.86 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.70–0.93), which was considered acceptable. For the total reliability analysis of the instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was applied, and a value of 0.83 (CI: 0.80–0.85) was obtained, which is considered very good.

PROCEDURE

The questionnaire was distributed to each student via email using the virtual program Google Classroom®. The informed consent of the students to participate in the study was at the beginning of the questionnaire as well as the indications to answer it. However, they were free to reject the evaluation if they did not wish to complete it during the process. Only the principal researcher had access to the data. No personal details such as telephone number, name, and address were required. Only one submission was considered for each student, and a maximum of 20 min was available to complete the questionnaire. The results were sent to the students’ emails after all the research was completed.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24.0. Descriptive statistics was applied to obtain percentages of categorical variables, measures of central tendency, and dispersion for numerical variables. Pearson’s χ2 test was used for bivariate analysis. Risk factors were established with the logistic regression model (logit model) using odds ratio (OR). All analyses were carried out considering p-value less than 0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

Regarding anxiety diagnoses according to the Zung Anxiety Self-Assessment Scale, the one that predominated most in dentistry students was “minimal to moderate anxiety,” followed by “no anxiety,” then “severe anxiety,” and finally “most extreme anxiety,” each with a frequency of 47.4%, 43.2%, 8.4%, and 1.0%, respectively.

Female students showed the most predominant tendency with 75.4%. In addition, students from private universities showed the highest percentage with 67%. Regarding age group, 63% of the students were under 23. The mean age was 23.19 ± 4.2 [Table 1]. In addition, 91.6% of all the students were single.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of sociodemographic variables in dentistry students and prevalence of anxiety

| Sociodemographic variables | Anxiety presence absence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | n | % | n (%) | n (%) |

| Gender | Female | 304 | 75.4 | 175 (57.6) | 129 (42.4) |

| Male | 99 | 24.6 | 54 (54.5) | 45 (45.5) | |

| Type of university | Public | 133 | 33.0 | 61 (45.9) | 72 (54.1) |

| Private | 270 | 67.0 | 168 (62.2) | 102 (37.8) | |

| Age (years) | ≤ 23 | 254 | 63.0 | 152 (59.8) | 102 (40.2) |

| > 23 | 149 | 37.0 | 77 (51.7) | 72 (48.3) | |

| Marital status | Single | 369 | 91.6 | 213 (57.7) | 156 (42.3) |

| Married or with partner | 34 | 8.4 | 16 (47.1) | 18 (52.9) | |

| Mean | SD | ||||

| Age | 23.19 | 4.2 | |||

Of 403 university students, the prevalence of anxiety in dentistry students was 56.8% (95% CI: 51.9–61.7). The female students had a prevalence of 57.6%, students from private university had a prevalence of 62.2%, 23-year-old students or younger of 59.8%, and single students of 57.7% [Table 1].

According to the psychological or affective symptoms associated with society, the results showed that there was a statistically significant association between the gender of dentistry students and Q4 (I feel like I’m falling apart and going to pieces) (p = 0.038) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association of psychological or affective symptoms according to the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale in dentistry students

| Never or rarely | Sometimes | Often | Usually or all the time | Gender | Type of university | Age group | Marital status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p | p | p | p | |

| Q1. I feel more nervous and anxious than usual. | 72 (17.9) | 238 (59.1) | 67 (16.6) | 26 (6.5) | 0.215 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.865 |

| Q2. I feel afraid for no reason at all. | 167 (41.4) | 191 (47.4) | 37 (9.2) | 8 (2.0) | 0.570 | 0.081 | 0.820 | 0.225 |

| Q3. I get upset easily or feel panicky. | 224 (55.6) | 129 (32.0) | 32 (7.9) | 18 (4.5) | 0.865 | 0.338 | 0.001 | 0.364 |

| Q4. I feel like I’m falling apart and going to pieces. | 269 (66.7) | 104 (25.8) | 24 (6.0) | 6 (1.5) | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.983 | 0.297 |

| Q5. I feel that everything is all right and nothing bad will happen. | 58 (14.4) | 208 (51.6) | 101 (25.1) | 36 (8.9) | 0.122 | 0.010 | 0.289 | 0.406 |

In contrast, the type of university of dentistry students was significantly associated with the following questions: Q4 (I feel like I’m falling apart and going to pieces) and Q5 (I feel that everything is all right and nothing bad will happen) (p = 0.010 for both) [Table 2].

Finally, regarding age group, a significant association was found in questions Q1 (I feel more nervous and anxious than usual) and Q3 (I get upset easily or feel panicky) (p <0.001 for both) [Table 2].

Statistically significant associations were obtained between the gender of dentistry students and Q6 (My arms and legs shake and tremble), Q7 (I am bothered by headaches, neck, and back pains), Q9 (I feel calm and can sit still easily), Q10 (I can feel my heart beating fast), Q16 (I have to empty my bladder often), Q17 (My hands are usually dry and warm), Q18 (My face gets hot and blushes), and Q19 (I fall asleep easily and get a good night’s rest) (p = 0.038, p = 0.004, p < 0.001, p = 0.033, p = 0.014, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p = 0.015, respectively) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association of somatic symptoms according to the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale in dentistry students

| Never or rarely | Sometimes | Often | Usually or all the time | Gender | Type of university | Age group | Marital status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p | p | p | p | |

| Q6. My arms and legs shake and tremble. | 283 (70.2) | 93 (23.1) | 21 (5.2) | 6 (1.5) | 0.038 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.039 |

| Q7. I am bothered by headaches, neck and back pains. | 102 (25.3) | 170 (42.2) | 85 (21.1) | 46 (11.4) | 0.004 | 0.049 | 0.126 | 0.044 |

| Q8. I feel weak and get tired easily. | 132 (32.8) | 159 (39.5) | 84 (20.8) | 28 (6.9) | 0.321 | 0.006 | 0.370 | 0.238 |

| Q9. I feel calm and can sit still easily. | 37 (9.2) | 155 (38.5) | 130 (32.3) | 81 (20.1) | <0.001 | 0.018 | 0.174 | 0.254 |

| Q10. I can feel my heart beating fast. | 239 (59.3) | 110 (27.3) | 44 (10.9) | 10 (2.5) | 0.033 | 0.520 | 0.002 | 0.583 |

| Q11. I am bothered by dizzy spells. | 267 (66.3) | 109 (27.0) | 19 (4.7) | 8 (2.0) | 0.604 | 0.180 | 0.539 | 0.027 |

| Q12. I have fainting spells or feel faint. | 366 (90.8) | 29 (7.2) | 6 (1.5) | 2 (5) | 0.084 | 0.798 | 0.227 | 0.095 |

| Q13. I can breathe in and out easily. | 21 (5.2) | 57 (14.1) | 111 (27.5) | 214 (53.1) | 0.795 | 0.660 | 0.167 | 0.020 |

| Q14. I get feelings of numbness and tingling in my fingers and toes. | 283 (70.2) | 91 (22.6) | 23 (5.7) | 6 (1.5) | 0.598 | 0.048 | 0.162 | 0.492 |

| Q15. I am bothered by stomachache or indigestion. | 164 (40.7) | 153 (38.0) | 66 (16.4) | 20 (5.0) | 0.093 | 0.008 | 0.224 | 0.585 |

| Q16. I have to empty my bladder often. | 87 (21.6) | 208 (51.6) | 85 (21.1) | 23 (5.7) | 0.014 | 0.072 | 0.419 | 0.117 |

| Q17. My hands are usually dry and warm. | 146 (36.2) | 147 (36.5) | 64 (15.9) | 46 (11.4) | <0.001 | 0.677 | <0.001 | 0.603 |

| Q18. My face gets hot and blushes. | 225 (55.8) | 131 (32.5) | 36 (8.9) | 11 (2.7) | <0.001 | 0.138 | 0.082 | 0.669 |

| Q19. I fall asleep easily and get a good night’s rest. | 93 (23.1) | 160 (39.7) | 90 (22.3) | 60 (14.9) | 0.015 | 0.125 | 0.674 | 0.652 |

| Q20. I have nightmares. | 176 (43.7) | 176 (43.7) | 34 (8.4) | 17 (4.2) | 0.315 | 0.038 | 0.569 | 0.475 |

The type of university of dentistry students was significantly associated with: Q6 (My arms and legs shake and tremble), Q7 (I am bothered by headaches, neck, and back pains), Q8 (I feel weak and get tired easily), Q9 (I feel calm and can sit still easily), Q14 (I get feelings of numbness and tingling in my fingers and toes), Q15 (I am bothered by stomachache or indigestion), and Q20 (I have nightmares) (p < 0.001, p = 0.049, p = 0.006, p = 0.018, p = 0.048, p = 0.008, p = 0.038, respectively) [Table 3].

Additionally, a statistically significant association was obtained between age group and Q6 (My arms and legs shake and tremble), Q10 (I can feel my heart beating fast), and Q17 (My hands are usually dry and warm) (p < 0.001, p = 0.002, p < 0.001, respectively) [Table 3].

Finally, a statistically significant association was obtained between marital status and Q6 (My arms and legs shake and tremble), Q7 (I am bothered by headaches, neck and back pains), Q11 (I am bothered by dizzy spells), and Q13 (I can breathe in and out easily) (p = 0.039, p = 0.044, p = 0.027, p = 0.020, respectively) [Table 3].

The regression model shows that the type of university variable influenced the development of anxiety in dentistry students. According to the univariate logistic regression model, it can be seen that dentistry students from private universities were 94% more likely to develop anxiety in comparison to students from public university (OR = 1.94; CI: 1.28–2.96). Additionally, when the multivariate logistic regression model (logit model) was employed related to the university type variable (X3), private university students were 98% more likely to develop anxiety compared with public university students (OR = 1.98; CI: 1.29–3.02). On the contrary, the variable age group (X1), gender (X2), and marital status (X4) were not considered as significant influencing factors to develop anxiety (p > 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models of anxiety in dentistry students according to associated factors

| Associated factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Categories | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (X1) Age group (years) |

≤ 23 | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 | — |

| > 23 | 0.110 | 0.72 | 0.48–1.08 | 0.247 | 0.77 | 0.49–1.20 | |

| ( X2) Gender |

Male | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 | — |

| Female | 0.598 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.78 | 0.550 | 1.15 | 0.72–1.84 | |

| ( X3) Type of University |

Public | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 | — |

| Private | 0.002 | 1.94 | 1.28–2.96 | 0.002 | 1.98 | 1.29–3.02 | |

| (X4) Marital Status | Single | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 | — |

| Married or with partner | 0.230 | 0.65 | 0.32–1.32 | 0.453 | 0.75 | 0.35–1.60 | |

OR = odds radio, 95% CI = confidence intervals at 95%

Logit model: All variables were entered in the statistical analysis of the multivariate model and the model was accepted since the significance of p = 0.011 was obtained according to the omnibus tests of model coefficients.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have reported that young university students have been particularly affected by mandatory social isolation. Therefore, they have shown signs and symptoms of anxiety due to uncertainty and the negative academic impact on the development of their classes.[15,22,28] Anxiety as a mechanism of physiological response to danger may increase due to a permanent feeling of insecurity or excessive fear, especially in these times of COVID-19 pandemic. This disease has been reported to be highly transmissible, to the extent that an infected person could infect up to five or six people around them (R0 = 5.7; 95% CI: 3.8–8.9) in a period of 6–9 days. For this reason, many governments of different countries established the mandatory social isolation as an urgent measure. Hence, the adaptation to a virtual study mode for students in general[3,10,29,30,31] has been a necessity. Virtual classes in this context, as has been done since March to date (October 2020), represent new challenges for university students of health sciences since the lack of adaptation to this situation could affect their academic development.[10,14] Additionally, the real or false massive information (infodemic) regarding COVID-19, which is circulating in the media and social networks, could negatively affect the mental health of students and thus increase their anxiety levels.[14,15,32]

This research found that the prevalence of anxiety in Peruvian dentistry students in the three universities evaluated was 56.8% (95% CI: 51.9–61.7). This shows that more than half of the students had symptoms of anxiety during mandatory social isolation. These results are consistent with what it was reported by Odriozola et al.[30] and Wang and Zhao,[17] who in their studies at a university in Spain and China, respectively, concluded that most students developed anxiety. On the contrary, both variables, type of university and gender, were associated with a psychological or affective symptom of anxiety and with seven or eight somatic symptoms, respectively. Age group was associated with two psychological or affective symptoms and three somatic symptoms. Finally, marital status was only associated with four somatic symptoms.

Studies conducted in China and Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that the female students developed significantly more symptoms of anxiety than the male students.[17,33] However, these results differ with what was obtained in this research. There were no statistically significant differences in anxiety according to sex, nor did it prove to be a risk factor according to the multivariate logistic regression analysis. This result is consistent with those obtained by Cao et al.[6] in China, as Cao’s research reported that sex had no significant influence on the development of anxiety. Although both studies conducted in China[6,17] measured anxiety levels, their contradictory results may be due to the fact that in the case of Cao et al.,[6] the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) was applied, whereas Wang and Zhao H[17] used the 20-item Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS).[23] In contrast, regarding gender, the differences in anxiety levels obtained with the SAS in our study compared to what was reported by Wang and Zhao[17] are probably because Wang and Zhao assessed anxiety levels globally in all professional careers related to sciences and humanities at 26 universities. They applied the bivariate statistical analysis, whereas in this research, anxiety levels were evaluated specifically in dentistry students from three universities applying a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

About age group, this study showed that more symptoms of anxiety were found in young students, but not significantly. These findings are similar to the ones reported by Ozamiz et al.[15] and Kang et al.[34] in Spain and China, respectively. This could indicate that age is not a risk factor for developing anxiety when the cut-off point of comparison ranges from 23 to 25 years of age.[15,34,35] However, in another study conducted in China, anxiety was significantly associated with the age group when the cut-off point was at 35 years of age.[36]

In this study, marital status was not considered a risk factor for the development of anxiety nor was associated with the presence of anxiety in students that were single, married, or with partner. These results were similar to what was reported by Kang et al.[34] In contrast, Tan et al.[35] reported that marital status was significantly associated with the presence of anxiety and reported marriage as a variable of risk factor. However, it should be noted that this study was conducted in health professionals and not in university students.

In this research, descriptive analysis showed that dentistry students from private universities were more anxious than students from public universities. In addition, when assessing the OR in the logit model considering its CI, it can be seen that students from private universities may be two or three times more likely to develop anxiety in comparison to students from public universities. This situation is probably due to the fact that students from private universities are not only concerned about doing their homework and taking examinations but also tuition and fees for dental school, which are usually expensive. Although many of them are not the ones who pay directly, the weak economy due to the pandemic could have affected families. This allows us to suggest that unemployment of the supporting parent or monthly income should be included in future investigations as risk factors associated with anxiety and be evaluated in a logit model.[6,14]

This study had some limitations. For example, students could not be evaluated in person. At the time of the survey, the country was in national emergency and mandatory social isolation.[37] Another limitation was that socioeconomic factors, place of residence, and number of people with whom the student lives could not be included in the logit model.[6,14,33] It was also not possible to consider students of all academic years. At the starting date of classes (May 2020), there were very few students enrolled and others dropped out of university in the first three years, especially in private universities. Additionally, the association of anxiety to distance education could not be evaluated since all the students included in this research were taking this learning modality.

It is recommended to assess anxiety levels in another student population in provinces of Peru and in other parts of the world. In contrast, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the impact of isolation on the development of anxiety of university students in a long-term. Similarly, it is highly recommended that the authorities of the various universities take into account the organization of plans and strategies[1,14,15] for the mental health care of their students due to social isolation. They could prevent the increase of anxiety levels by identifying them at an early stage and taking action on them.[10]

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, more than half of the Peruvian dentistry students from the three universities considered in this research presented mild-to-severe anxiety. About 98% of the students from private universities are more likely to develop anxiety in comparison to students from public universities. Variables such as gender, age group, and marital status were not considered influential factors for developing anxiety. These results must be taken into account, since excessive anxiety can affect the academic performance of the dental student and with more reason, their mental and physical health, causing psychological and/or somatic disorders. Hence, it is ideal that university authorities take corresponding measures and organize programs to safeguard mental health of students. This action would counteract one of the negative effects that has increased as a consequence of this pandemic: the anxiety.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None to declare.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

They conceived the research idea (C. F. C.-R, J. M. C. M.), elaborated the manuscript (C. F. C.-R., J. M. C.-M., L. C. C.-L.), collected and tabulated the information (C. F. C.-R., A. S. A.-M.), carried out the bibliographic search (L. A. C.-G., M. I. L.-C., A. S. A.-M., R. A. R.), interpreted the statistical results and helped in the development from the discussion (C. F. C.-R.), he performed the critical revision of the manuscript (C. F. C.-R., J. M. C.-M., M. I. L.-C., R. A. R., A. S. A.-M., L. A. C.-G., L. C. C.-L.). All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

This research was approved by the Committee of the Research Institute of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega University with the resolution 033-2020-RUIGV.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the study results are available from the author (Dr César F. Cayo-Rojas, e-mail: cesarcayorojas@gmail.com) on request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Social Responsibility team of the San Juan Bautista Private University, School of Stomatology, Lima, Peru, for their constant support in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. [Cited July 18, 2020];Lancet [Internet] 2020 395:37–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7133594/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports [Internet] 2020. [accessed October 19, 2020]. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/

- 3.Idoiaga N, De Montes LG, Valencia J. Understanding an ebola outbreak: Social representations of emerging infectious diseases. J Health Psychol. 2017;22:951–60. doi: 10.1177/1359105315620294. 10.1177/1359105315620294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trickett S. Supera la ansiedad y la depresión. 5ta ed. España: Hispano Europea; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quek TT, Tam WW, Tran BX, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Ho CS, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: A meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152735. 10.3390/ijerph16152735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar B, Shah MAA, Kumari R, Kumar A, Kumar J, Tahir A. Depression, anxiety, and stress among final-year medical students. Cureus. 2019:11e4257. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4257. 10.7759/cureus.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez C, Chichón J, León F, Alipazaga P. Mental disorders in medical students of three universities in Lambayeque, Perú. Rev Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;79:197–206. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.20453/rmh.v27i4.2988 . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayo-Rojas CF, Agramonte-Rosell RC. Challenges of virtual education in dentistry in times of COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Cubana Estomatol. 2020;57:e3341. Available at: http://www.revestomatologia.sld.cu/index.php/est/article/view/3341/1793 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Balas M, Al-Balas HI, Jaber HM, Obeidat K, Al-Balas H, Aborajooh EA, et al. Correction to: Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:513. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02428-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatterjee K, Chauhan VS. Epidemics, quarantine and mental health. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76:125–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.017. 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meo SA, Abukhalaf AA, Alomar AA, Sattar K, Klonoff DC. COVID-19 pandemic: Impact of quarantine on medical students’ mental wellbeing and learning behaviors. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:43–8. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12:e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozamiz N, Dosil M, Picaza M, Idoiaga N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern SpainCad. Saúde Pública [Internet] 2020;36:e00054020. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csp/v36n4/en_1678-4464-csp-36-04-e00054020.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in china: A cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Zhao H. The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in Chinese university students. Front Psychol [Internet] 2020;11:1168. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01168. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7259378/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galván-Molina J, Jiménez-Capdeville M, Hernández-Mata J, Arellano-Cano J. Sistema de tamizaje de psicopatología en estudiantes de Medicina [Psychopathology screening in medical school students] Gac Med Mex. 2017;153:75–87. Available at: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=71208 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez-López JL, Arenas-Osuna J, Angeles-Garay U. [Depression, anxiety and suicide risk symptoms among medical residents over an academic year] Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2015;53:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng W, Chen R, Wang X, Zhang Q, Deng W. Prevalence of mental health problems among medical students in China: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15337. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015337. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawzy M, Hamed SA. Prevalence of psychological stress, depression and anxiety among medical students in Egypt. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shawahna R, Hattab S, Al-Shafei R, Tab’ouni M. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Palestinian medical students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:244. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. Ethical principles for medical research on human beings. Fortaleza: 64th General Assembly of the WMA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zung W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–79. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lusilla M, Sánchez A, Sanz C, López J. Validación estructural de la escala heteroevaluada de ansiedad de Zung (XXVIII Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría) Anales de Psiquiatría. 1990;6(Suppl 1):39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peña-Casanova J, Aguilar M, Beltrán-Serra I, Santacruz P, Hernández G, Insa R. Normalización de instrumentos cognitivos y funcionales para la evaluación de la demencia (NORMACODEM) Neurología. 1997;12:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin Arribas MC. Diseño y validación de cuestionarios. Matronas Profesión [Internet] 2004;5:23–9. Available from: https://www.enferpro.com/documentos/validacion_cuestionarios.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stangvaltaite-Mouhat L, Puriene A, Chalas R, Hysi D, Katrova L, Nacaite M, et al. Self-reported psychological problems amongst undergraduate dental students: A pilot study in seven European countries. Eur J Educ. 2020;24:341–250. doi: 10.1111/eje.12505. 10.1111/eje.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1470–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odriozola P, Planchuelo A, Irurtia MJ, De Luis R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res [Internet] 2020;290:113108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaparounaki CK, Patsali ME, Mousa DV, Papadopoulou EVK, Papadopoulou KKK, Fountoulakis KN. University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cayo-Rojas CF, Miranda-Dávila AS. Higher medical education facing the COVID-19 infodemia. Educ Med Super. 2020;34:e2524. Available at: http://www.ems.sld.cu/index.php/ems/article/view/2524 . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azad N, Shahid A, Abbas N, Shaheen A, Munir N. Anxiety and depression in medical students of a private medical college. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29:123–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cayo C, Castro J, Agramonte R. Strategies to decrease anxiety in dental students due to social isolation. Rev Cubana Estomatol [Internet] 2021;58 http://www.revestomatologia.sld.cu/index.php/est/article/view/3542 . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the study results are available from the author (Dr César F. Cayo-Rojas, e-mail: cesarcayorojas@gmail.com) on request.