Abstract

Hazardous drinkers with emotional vulnerabilities (e.g., elevated anxiety sensitivity) remain an underserved group. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a single session remotely-delivered personalized feedback intervention (PFI) targeting alcohol (mis)use and anxiety sensitivity among college students. Hazardous drinkers with elevated anxiety sensitivity (N=125; 76.8% female; Mage = 22.14; 66.4% racial/ethnic minorities) were randomized to receive the integrated PFI (n=63) or attention control (n=62). Follow-up assessments were conducted one-week, one-month and three-months post-intervention. Latent growth curve modeling was used to test pilot outcomes. It was feasible to recruit and retain hazardous drinking students with elevated anxiety sensitivity through follow-up with no group differences in retention. The integrated PFI was rated as more acceptable than the control with medium/large differences (p’s<0.004; d’s=0.54–0.80). The integrated PFI group had statistically significantly greater change in primary outcomes: motivation, hazardous alcohol use, and anxiety sensitivity (p’s <0.05; d’s=0.08–0.37) with larger within-group effect sizes (d’s=0.48–0.61) than in control (d’s=0.26–0.54). Despite a small sample size, this one-session intervention offers promise among a high-risk group of drinkers with emotional vulnerabilities. The computer-based format may allow for mass distribution of a low-cost intervention in the future; however, follow-up testing in larger samples is needed.

Keywords: Transdiagnostic, Integrated, Comorbidity, Affect, Technology, Intervention

Alcohol (mis)use is a leading cause of preventable death (Degenhardt et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2019). Yet, ‘high-risk’ drinking, alcohol use disorder (AUD), and alcohol-releated deaths have been steadily increasing (B. F. Grant et al., 2017; White et al., 2020). College drinking is particularly relevant as a majority of college students drink, with many drinking heavily (Johnston et al., 2016; Merrill & Carey, 2016). Indeed, rates of AUD tend to peak during college years (Hasin & Grant, 2004). Alcohol (mis)use among college students is associated with numerous consequences including blackouts, injuries, and death (Hingson et al., 2017), stressing the need for increased efforts in college settings.

In addition to AUD, it is practical from a public health standpoint to identify students who may be at risk for developing AUD (Hagman, 2016) and provide early intervention. Although there are various forms of alcohol (mis)use (e.g., at-risk, excessive, harmful) a focus on hazardous drinkers, particularly in college settings, may be beneficial (DeMartini & Carey, 2009). Hazardous drinking is a pattern of (mis)use that increases the risk of alcohol-related problems and consequences (World Health Organization, 2015). Typically, hazardous drinkers are identified by cut-off scores on standardized measures (e.g., Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT]; Saunders et al., 1993). Approximately one third to one half of college students report past-year hazardous drinking (Paulus & Zvolensky, 2020; Read et al., 2016), indicating that wide-ranging interventions may be needed.

Yet, most hazardous drinkers receive no treatment (Blanco et al., 2008; Cunningham & Breslin, 2004). Despite the relative availability of health/mental health resources on college campuses, students (particularly those who are hazardous drinkers) report little or no interest in treatment (Capron et al., 2018; Eisenberg et al., 2007), limiting the impact of traditional interventions. One way to better reach hazardous drinking students is through the use of technology, such as computer-delivered/online interventions (e.g., personalized feedback interventions [PFIs]; Miller et al., 2013). PFIs present individuals with personalized drinking profiles (e.g., patterns, risk factors, consequences) and normative comparisons of consumption (e.g., contrasting drinking levels with normative data of peers) along with strategies for alcohol reduction (Walters & Neighbors, 2005). By accentuating discrepancies between what an individual perceives to be normative drinking and documented drinking norms, one’s motivation to change drinking can be enhanced (Miller et al., 2013). Online PFIs have been successful in reducing alcohol (mis)use among college students overall (Black et al., 2016; Kaner et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2013; Prosser et al., 2018); however, PFIs may be relatively less effective among hazardous drinkers (Baumann et al., 2018) suggesting the need for enhancements among this clinically-relevant subgroup of drinkers.

The presence of comorbid emotional syndromes (i.e., symptoms and disorders of anxiety/depression; Leventhal & Zvolensky, 2015) may be one source of treatment complication among hazardous drinkers. Comorbidity between emotional syndromes and alcohol (mis)use is frequent and associated with poorer clinical outcomes (B. F. Grant et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2015). For example, hazardous drinkers with emotional syndromes (i.e., emotionally-vulnerable hazardous drinkers) are at risk for more severe mental health and alcohol-related symptoms (Baker et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2020). Furthermore, alcohol (mis)use and emotional syndromes impact one another reciprocally over time (Kushner et al., 2000), with a need for integrated alcohol+emotion interventions (Schumm & Gore, 2016). However, there are numerous potential comorbidity patterns both within emotional syndromes (e.g., social anxiety+panic, depression+posttraumatic stress; Brown et al., 2001; Goldstein-Piekarski et al., 2016) and between emotional syndromes and alcohol (mis)use (e.g., depression+alcohol, social anxiety+alcohol, posttraumatic stress+alcohol; Brière et al., 2014; Debell et al., 2014; Schneier et al., 2010) further complicating the development of integrated treatments. Given the underlying similarities between various emotional syndromes (Norton & Paulus, 2017), a transdiagnostic intervention approach could potentially streamline integrated treatments by reducing the need for interventions focused on each possible comorbidity permutation (Norton & Paulus, 2016). Transdiagnostic emotional interventions have been shown to be as effective as diagnosis-specific interventions (Pearl & Norton, 2017). Thus, a PFI focused on hazardous drinking and emotional syndromes (from a transdiagnostic perspective) would be a novel innovation.

Past work has shown that a (non-alcohol) depression-focused PFI can reduce depression among students (Geisner et al., 2006), documenting the potential for a PFI framework for emotional syndromes. However, alcohol-based PFIs have been been relatively less effective among students with elevated depression (Geisner et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2020) and anxiety (Terlecki et al., 2012). Thus, an integrated PFI for hazardous drinking+emotional syndromes may need to be augmented with other intervention components for hazardous drinkers with emotional vulnerabilities.

One such augmentation could be to therapeutically target theory-driven mechanistic candidates common to each condition (i.e., emotion and alcohol) in an effort to address an underlying functional impairment rather than a particular cluster of symptoms (Norton & Paulus, 2016). Anxiety sensitivity may be a prime target for integrated alcohol + emotion intervention as it is a well-documented risk/maintenance factor for both emotional syndromes (Naragon-Gainey, 2010; Olatunji & Wolitzky-Taylor, 2009) and hazardous drinking/AUD (DeMartini & Carey, 2011; Schmidt et al., 2007). Moreover, approximately three quarters of hazardous drinking students report elevated anxiety sensitivity (Paulus & Zvolensky, 2020), making it a broadly relevant target. Imporantly, anxiety sensitivity can be reduced via even brief computer-based intervention (Keough & Schmidt, 2012). Furthermore, reduction of anxiety sensitivity is associated with improved emotional symptoms (Gallagher et al., 2013; Paulus, Brandt, et al., 2020) and alcohol (mis)use, (Olthuis et al., 2015; Paulus et al., 2019; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2018).

Taken together, one approach to enhance PFIs for emotionally vulnerable hazardous drinkers may be to directly target a transdiagnostic mechanistic candidate relevant to the range of emotional syndromes and their co-occurance with hazardous drinking. The current study utilized a well-established alcohol PFI framework augmented with anxiety sensitivity education and reduction techniques in an effort to develop an efficient integrated treatment for emotionally vulnerable (i.e., high anxiety sensitivity) hazardous drinkers. Additionally, the computer-delivered format may maximize the potential reach of such an approach. To this end, the current study had three primary aims: (1) demonstrating the feasibility of developing an integrated anxiety sensitivity+hazardous drinking PFI, recruiting hazardous drinkers with elevated anxiety sensitivity in a college setting, and implementing the intervention remotely, (2) assessing the acceptability of the intervention, and (3) evaluating initial outcomes of the novel PFI relative to control with three month follow-up in a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT). We anticipated that we could develop the integrated intervention based on separate lines of past work examining PFIs for alcohol use (Miller et al., 2013) and anxiety sensitivity reduction programs (Keough & Schmidt, 2012), recruit hazardous drinking students with elevated anxiety sensitivity (Paulus & Zvolensky, 2020), and remotely deliver the intervention with acceptable retention (i.e., similar to that of past PFI work) through three month follow-up. We hypothesized that participants receiving PFI would provide higher acceptability ratings than those receiving control. Regading primary outcomes, it was expected that those in the PFI condition would evidence greater improvements in motivation to change their alcohol use, hazardous alcohol use, and anxiety sensitivity from baseline through three month follow-up. Finally, as secondary outcomes, reductions in emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression) were examined as well as negative reinforcement drinking motives (drinking to cope with anxiety, drinking to cope with depression, and drinking to conform), which have been previously linked to anxiety sensitivity and alcohol misuse (Stewart et al., 2001).

Method

Participants

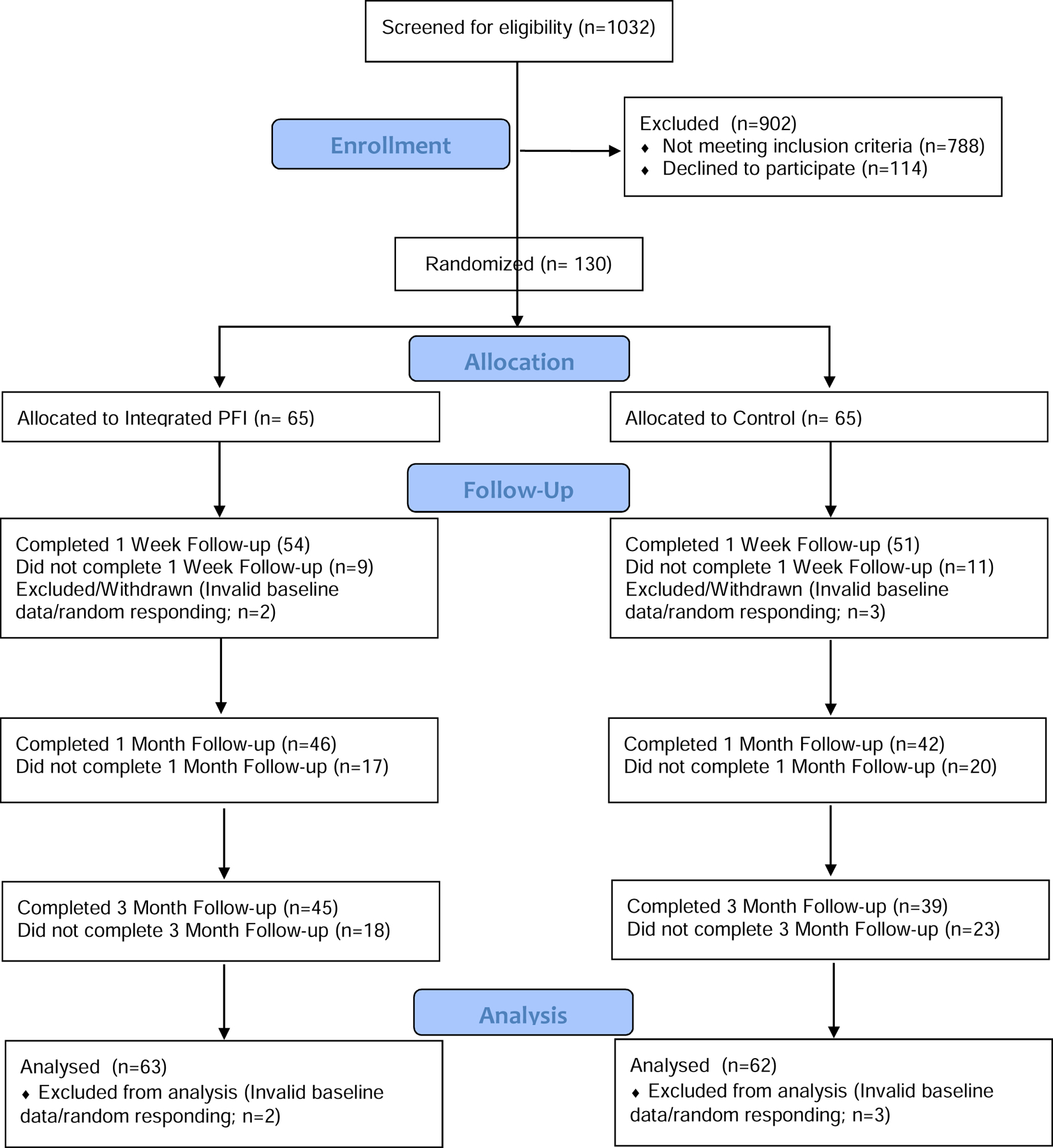

The sample consisted of students attending a large southwestern university. Although 130 were enrolled (Figure 1), five were excluded due to random responding on baseline measures,1 yielding 125 participants (Mage = 22.14; SD=4.06) for analysis (63 PFI; 62 control). The majority of the sample identified as female (76.8%) and was racially/ethnically diverse with 36.0% identifying as Latinx, 33.6% White, 19.2% Asian, 8.8% Black, and 2.4% multi-racial.

Figure 1:

CONSORT chart of participant enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis

Procedure

This study involved three stages: (a) screening; (b) baseline assessment and single session computer-delivered program (PFI or control); and (c) follow-up assessments one-week, one-month, and three months post-baseline (Paulus, Gallagher, et al., 2020). Inclusion criteria included: (1) college students, (2) aged 18+, (3) elevated anxiety sensitivity, defined as 17+ on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007), consistent with documented cut-offs (Allan et al., 2014), and (4) hazardous drinking, defined as total scores of 8+ for males (7+ for females) on the AUDIT (Saunders et al., 1993). Exclusion criteria included current participation in alcohol, drug, or mental health treatment. This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA: F31AA024968) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited via print and online media (e.g., fliers, Facebook, university research pool/listservs).

Screening.

The screening survey was brief and designed for the current study. It was completed via Qualtrics, online. Interested individuals provided informed consent online then answered demographic and eligibility questions (approximately 10 minutes). Eligible individuals were invited to participate in an online treatment study and were emailed a link to the baseline.

Baseline.

Eligible individuals completed a baseline/pre-intervention survey (approximately 30 minutes). Participants then randomly received a computer-delivered program (PFI or control; see intervention below), approximately matched for time (one hour).

Follow-up.

Follow-up links were emailed to participants one-week, one-month, and three months after baseline. Links were active for seven days after which they were considered missed. Individuals missing a follow-up were still contacted to complete the next follow-up. Two automated email prompts were sent to individuals with incomplete follow-ups (a reminder 48-hours after the initial invitation and a warning 24-hours before link expiration). No other contact (e.g., telephone) was made.

Compensation.

For participation in the screening survey, university research pool course credit was offered. In addition, two ($50) electronic gift cards were raffled at the end of the study; all screened individuals were included in the raffle. Eligible participants who were enrolled in the trial were paid $30 in electronic gift cards for completing the baseline and $20 for completing each follow-up assessment. Participants could choose course credit as an alternative at each timepoint. Participants completing all portions received a $10 bonus.

Intervention

Personalized Feedback Intervention.

The novel integrated PFI was developed and modeled upon past PFIs targeting hazardous drinking (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2004). First, integrated (e.g., Stewart & Conrod, 2008) psychoeducation on the role of anxiety sensitivity in the development and maintenance of both emotional symptoms and alcohol misuse/drinking to cope with emotional symptoms was presented with visual content online. Comprehension questions were asked and on screen messages validated accurate responses and corrected inaccurate responses in real-time. All individuals in the study had elevated anxiety sensitivity and received uniform feedback on its potential risks for both emotional and alcohol-related outcomes, based on past research (DeMartini & Carey, 2011; Naragon-Gainey, 2010; Olatunji & Wolitzky-Taylor, 2009; Schmidt et al., 2007). Then, three brief videos (~four minutes each) demonstrated interoceptive exposure exercises (straw breathing, overbreathing, and headrush/head between legs; Boswell et al., 2013) and discussed how, over time, they can potentially reduce the risk for unpleasant emotional symptoms and alcohol misuse; participants were instructed to practice the exercises along with the video and were given permanent access to the videos. A worksheet (with a link to save the document) was provided including instructions for 14 interoceptive exposure examples as well as additional (non-alcohol) coping strategies (e.g., vigorous exercise, deep breathing). Next, participants’ drinking behavior (e.g., drinks per week and AUDIT total score) was contrasted with perceived and actual norms tailored to their age and gender (determined via computer program/algorithm); graphs of these data were presented as a means of normative comparison. Information regarding hazardous drinking (e.g., cost, health consequences) was presented along with potential strategies for alcohol reduction (e.g., spacing drinks over time, setting limits on the number of alcohol beverages before initiating a drinking session). Norms for alcohol use were based on survey data from over 18,000 college students in multiple universities in the United States (CORE Institute, 2015).

Attention Control.

Participants received facts about the host university, retrieved from official university sources. To increase attention and match the format of the active condition, videos about the university were shown and questions about the university were asked. Correct responses were validated and inaccurate responses were corrected with on screen messages. Similar controls to PFI have been utilized previously (Young & Neighbors, 2019). There was no mention of emotional syndromes, anxiety sensitivity, alcohol, or coping in the control.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information (e.g., age, sex) was collected at the screening. and used to describe the sample and determine eligibility.

Alcohol History Questionnaire (AHQ; Filbey et al., 2008).

Drinking history (e.g., number of years drinking regularly) was described with the AHQ at screening.

Quality Control.

Four items (e.g., “If I am paying attention, I will select ‘2’”) were inserted throughout the baseline questionnaire battery to check for attention/quality control. Answering a quality control item incorrectly triggered a pop-up warning that failure to answer quality control items correctly would result in removal from the study.

Treatment Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (TCEQ; Devilly & Borkovec, 2000).

A modified version of the TCEQ was used to evaluate the acceptability of the PFI relative to control. One item assessed how logical “the program” seemed overall; two items assessed how successful participants thought the program would be in terms of reducing alcohol use and anxiety sensitivity, respectively. Items were rated on scales from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very). Two items also assessed anticipated reduction in alcohol use and anxiety sensitivity, respectively (0–100%). The TCEQ was administered after the assigned intervention (PFI or control).

The Alcohol Ladder (AL; Clair et al., 2011).

The AL is measure of current motivation to change alcohol use. Participants select one of 10 statements (e.g., “I have changed my drinking and will never go back to the way I drank before”) that best aligns with their current motivation level. The AL has demonstrated concurrent validity and predictive validity for treatment engagement (Hogue et al., 2010) It was administered at baseline and follow-ups.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 2001).

The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure of hazardous drinking. Although total scores are widely used (Babor et al., 2001; Saunders et al., 1993), the AUDIT has been found to have a correlated two-factor structure (Doyle et al., 2007; Maisto et al., 2000); the first three items (e.g., “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol”) assess alcohol consumption (frequency, quantity, and heavy episodic drinking) with no explicit measurement timeframe and the remaining items (e.g., “How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?”) assess alcohol-related problems/consequences over the past year (items 4–8) or lifetime (items 9–10). Items are rated on scales from 0 to 4 with various response anchors. The AUDIT was administered at screening (α=0.74) and the total score was utilized to identify hazardous drinking (8+ for men; 7+ for women) (Saunders et al., 1993). The first three items of the AUDIT (often used as a standalone measure [AUDIT-C]; Bush et al., 1998) were administered at baseline and follow-ups (α=0.64–0.71) to evaluate hazardous alcohol use over time. AUDIT-C items have been used to assess hazardous drinking (Reinert & Allen, 2007) with good test-retest reliability over time (Jeong et al., 2017).

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007).

The ASI-3 is an 18-item self-report measure of anxiety sensitivity. Items (e.g., “It scares me when my heart beats rapidly”) are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (very little) to 4 (very much) with no explicit timeframe. Elevated anxiety sensitivity was defined as total scores of 17 or greater (Allan et al., 2014). The ASI-3 shows good convergent and discriminant validity (Taylor et al., 2007) as well as invariance across sex, age, and race/ethnicity (Jardin et al., 2018). The ASI-3 was administered in the screening to determine eligibility as well as at baseline and follow-ups (α=0.87–0.94).

Mood Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire Short Form (MASQ; Watson & Clark, 1991).

The MASQ is a 30-item self-report measure of past-week symptoms. Items (e.g., “felt dizzy”) are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The MASQ has demonstrated convergent validity with other measures of anxiety and depression (Watson et al., 1995). The MASQ subscales assessing anxiety (MASQ-A; α=0.85–0.90) and depression (MASQ-D; α=0.90–0.93), were administered at baseline and follow-ups.

Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ; V. V. Grant et al., 2007).

The DMQ is a self-report measure of drinking motives with no explicit timeframe. It has demonstrated good test-retest reliability among college drinkers (V. V. Grant et al., 2007). The negative reinforcement drinking subscales were administered at baseline and follow-ups: drinking to cope with anxiety (DMQ-A; e.g., “to reduce my anxiety”; α=0.72–0.86), drinking to cope with depression (DMQ-D; e.g., “to stop me from dwelling on things”; α=0.94–0.97), and drinking to conform (DMQ-C; e.g., “so I won’t feel left out”; α=0.84–0.88).

Analytic Plan

Primary analyses were conducted in Mplus (version 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, 2015) using maximum likelihood. Maximum likelihood appropriately accounts for missing data as well as, if not better than, multiple imputation (Allison, 2003). First, descriptive statistics were calculated and baseline differences between groups were examined. Next, given maximum likelihood assumes that data are missing completely at random (MCAR; Allison, 2003), Little’s MCAR test was used to to test this assumption using SPSS (version 24); significance values <0.05 indicate that the MCAR assumption is violated and data are not MCAR. Next, to assess retention between conditions, binary logistic regression was used to examine condition (0=control; 1=PFI) as a predictor of each follow-up completion (0=missed; 1=completed). Effect sizes were calculated with Cohen’s d for frequency/proportions (i.e., of completed follow-ups; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Treatment acceptability was then evaluated with condition as a predictor of the five modified TCM items; age, sex, and racial/ethnic minority status were included as covariates. Cohen’s d for mean differences were calculated (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

To assess primary outcomes, three latent growth curve models were run with condition (0=control; 1=active) as a predictor of intercept and slope for motivation (AL), hazardous alcohol use (AUDIT-C), and anxiety sensitivity (ASI-3); five additional models tested secondary outcomes of anxiety (MASQ-A), depression (MASQ-D), drinking to cope with anxiety (DMQ-A), drinking to cope with depression (DMQ-D), and drinking to conform (DMQ-C). For models with statistically significant effects of condition on slope, within-group slopes were evaluated separately by condition. Slopes were modeled from baseline/pre-treatment through three month follow-up; models for hazardous drinking and anxiety sensitivity included data from the screening and were modeled piecewise with the first slope segment representing change from screening to baseline and the second slope segment representing change from basline through three month follow-up. A piecewise model was conducted so that change following the intervention (baseline to follow-up) could be separated from random change occurring before the intervention (screening to baseline). All models included age, sex, and racial/ethnic minority status as covariates2. Intercepts were centered at the first timepoint and slopes were estimated with shape factors such that factor loadings were fixed at 0 for the first measurement, fixed to 1 for the three month follow-up, and freely estimated in between. This method yields average slope values capturing total non-linear change (e.g., Gallagher et al., 2014).

Repeated measures Cohen’s d’s were calculated to index effect sizes for between and within group trajectories (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Morris & DeShon, 2002). Within-group effect sizes were calculated both overall (i.e., from baseline to three month follow-up) as well as between all adjacent measurements (e.g., baseline to one-week follow-up). The repeated measures calculation includes a correction for the correlation between scores at the two time-points. Model fit was assessed using root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). RMSEA values of .06 or lower, CFI and TLI values of 0.90 or greater (although ideally 0.95 or greater), and SRMR values of 0.08 or less indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Cohen’s d values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 correspond to small, medium, and large effects (Cohen, 1988) with values <0.2 representing trivial effect sizes (Sawilowsky, 2009).

Results

Descriptive.

On average, participants reported having their first alcoholic beverage at age 16.30 (SD=2.67) with of 2.97 years (SD=3.38) of being a “regular drinker.” More than half (63.4%) reported having attempted to quit or reduce drinking at some point in their life; among those reporting an attempt, there was an average of 2.23 (SD=3.01) lifetime attempts, consistent with past work among among college students with relatively severe AUD (e.g., Rinker & Neighbors, 2015). Enrolled participants (N=125) had elevated anxiety sensitivity (MASI-3=36.13) and were hazardous drinkers (MAUDIT=12.75) at screening. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in ASI-3, AUDIT-total, AUDIT-C, age, sex, or racial/ethnic minority status at screening (all p’s>0.157). Means over time for each group are presented in Table 1 with effect sizes in Table 2. Little’s MCAR test demonstrated that data were indeed MCAR at each follow-up [one week: χ2(7)=5.59, p=0.589; one month: χ2(5)=1.99, p=0.850; three month: χ2(4)=4.64, p=0.326] justifying the use of maximum likelihood for primary analyses.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics and means (SDs) over time by condition

| Screen | BL | W1 | M1 | M3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | PFI | 22.25 (4.18) | - | - | - | - |

| Con | 22.02 (3.97) | - | - | - | - | |

| Sex | PFI | 79.4% | - | - | - | - |

| Con | 74.2% | - | - | - | - | |

| Minority Status | PFI | 66.7% | - | - | - | - |

| Con | 66.1% | - | - | - | - | |

| AL | PFI | - | 4.91 (2.96) | 5.94 (2.65) | 5.77 (3.02) | 6.05 (3.35) |

| Con | - | 5.50 (2.78) | 5.72 (2.67) | 5.59 (2.51) | 6.39 (2.87) | |

| AUDIT-C | PFI | 5.41 (2.29) | 5.41 (2.41) | 4.98 (2.25) | 4.35 (2.30) | 3.99 (2.03) |

| Con | 5.29 (1.78) | 5.23 (1.89) | 5.03 (1.84) | 4.67 (1.93) | 4.55 (1.72) | |

| ASI-3 | PFI | 35.92 (12.41) | 31.33 (16.69) | 29.84 (16.82) | 26.00 (19.06) | 24.07 (17.25) |

| Con | 36.34 (12.71) | 30.90 (14.54) | 29.95 (15.90) | 29.03 (15.50) | 26.59 (14.81) | |

| MASQ-A | PFI | - | 20.62 (8.32) | 20.83 (8.29) | 20.21 (9.05) | 18.64 (9.04) |

| Con | - | 19.61 (6.27) | 19.89 (6.47) | 19.29 (6.44) | 18.82 (6.29) | |

| MASQ-D | PFI | - | 33.51 (7.94) | 32.99 (9.06) | 32.92 (7.95) | 34.01 (8.02) |

| Con | - | 33.32 (8.27) | 33.99 (7.47) | 33.03 (8.72) | 32.14 (8.79) | |

| DMQ-A | PFI | - | 3.03 (0.99) | 3.20 (1.14) | 2.94 (1.11) | 2.81 (1.09) |

| Con | - | 2.88 (0.88) | 2.77 (1.01) | 2.56 (0.88) | 2.62 (1.03) | |

| DMQ-D | PFI | - | 2.64 (1.12) | 2.54 (1.32) | 2.43 (1.22) | 2.30 (1.29) |

| Con | - | 2.25 (1.01) | 2.11 (0.99) | 1.94 (0.84) | 1.98 (1.00) | |

| DMQ-C | PFI | - | 1.77 (0.80) | 1.92 (0.95) | 1.92 (0.92) | 1.80 (0.97) |

| Con | - | 1.76 (0.84) | 1.86 (0.88) | 1.74 (0.75) | 1.79 (0.93) | |

Notes: Age=Participant Age; Sex=Female (1); Male (0); Minority Status=Racial/Ethnic Minority (1); White (0); AL=Alcohol Ladder; AUDIT-C=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption; ASI-3=Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; MASQ=Mood Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; MASQ-A=Anxiety Subscale; MASQ-D=Depression Subscale; DMQ=Drinking Motives Questionnaire; DMQ-A=Anxiety Coping Subscale; DMQ-D=Depression Coping Subscale; DMQ-C=Conformity Subscale; PFI=Integrated Personalized Feedback Intervention; Con=Control; Screen=Screening; BL=Baseline/Pretreatment; W1=Week 1 Follow-up; M1=Month 1 Follow-up; M3=Month 3 Follow-up.

Table 2:

Effect size (Cohen’s d)

| Screen-BL | BL-W1 | W1-M1 | M1-M3 | BL-M3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | PFI | - | 0.48 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 0.48* |

| Con | - | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.26 | 0.26 | |

| AUDIT-C | PFI | −0.004 | −0.34 | −0.45 | −0.20 | −0.61* |

| Con | −0.05 | −0.16 | −0.28 | −0.08 | −0.54* | |

| ASI-3 | PFI | −0.41 | −0.16 | −0.43 | −0.20 | −0.53* |

| Con | −0.61 | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.22 | −0.39* | |

| MASQ-A | PFI | - | 0.03 | −0.09 | −0.23 | −0.25 |

| Con | - | 0.05 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.12 | |

| MASQ-D | PFI | - | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| Con | - | 0.12 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.14 | |

| DMQ-A | PFI | - | 0.24 | −0.47 | −0.17 | −0.24 |

| Con | - | −0.15 | −0.30 | 0.06 | −0.32 | |

| DMQ-D | PFI | - | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.40 |

| Con | - | −0.24 | −0.33 | 0.07 | −0.36 | |

| DMQ-C | PFI | - | 0.25 | 0.01 | −0.19 | 0.04 |

| Con | - | 0.16 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

Notes: AL=Alcohol Ladder; AUDIT-C=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption; ASI-3=Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; MASQ=Mood Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; MASQ-A=Anxiety Subscale; MASQ-D=Depression Subscale; DMQ=Drinking Motives Questionnaire; DMQ-A=Anxiety Coping Subscale; DMQ-D=Depression Coping Subscale; DMQ-C=Conformity Subscale; PFI=Integrated Personalized Feedback Intervention; Con=Control; Values represent change between specified measurement periods; Screen=Screening; BL=Baseline/Pretreatment; W1=Week 1 Follow-up; M1=Month 1 Follow-up; M3=Month 3 Follow-up. Negative values for Cohen’s d indicate score decreases; positive values indicate score increases.

p<0.05 for the trajectory from baseline to three month follow-up.

Feasibility/Retention.

There was acceptable retention with 84.0% at one-week, 70.4% at one-month, and 67.2% at three month follow-up, which is simimilar to past work (e.g., 68% retention through one month; Young & Neighbors, 2019). There were no statistically significant differences between conditions in completion of week-one (β=0.07, 95%CI [−0.19, 0.33] p=0.597, d=0.14), month-one (β=0.07, 95%CI [−0.14, 0.28] p=0.517, d=0.14), or month-three (β=0.11, 95%CI [−0.10, 0.31] p=0.307, d=0.21; see Figure 1) follow-ups.

Acceptability.

Examining acceptability showed that those in the PFI group (M=6.91) rated their “program” as more logical than those in the control rated theirs (M=5.83; β=0.30, 95%CI [0.13, 0.46] p<0.001, d=0.62). The PFI group anticipated greater success in reducing alcohol use (M=5.26; β=0.26, 95%CI [0.09, 0.43], p=0.002, d=0.57) than control (M=4.16); the PFI group also anticipated greater success in reducing anxiety sensitivity (M=5.66; β=0.25, 95%CI [0.08, 0.43], p=0.004, d=0.54) than control (M=4.71). The PFI group reported significantly greater anticipated reductions in alcohol use (M=40.88%; β=0.32, 95%CI [0.15, 0.48], p<0.001, d=0.68) and anxiety sensitivity (M=44.86%; β=0.38, 95%CI [0.23, 0.52], p<0.001, d=0.80) than control (M=25.52% and 29.09%, respectively).

Motivation (AL).

In the model examining motivation to change alcohol use (RMSEA<0.01, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.05), condition was not a statistically significant predictor of intercept (β=−0.11, 95%CI [−0.32, 0.10], p=0.307). Condtion was a statistically significant predictor of slope (β=0.43, 95%CI [0.06, 0.81], p=0.023, d=0.08). There was a statistically significant increase in motivation to change alcohol for the PFI group (β=1.20, 95%CI [0.54, 1.87], p<0.001, d=0.48); the increase in motivation for the control group was smaller and not statistically significant (β=0.77, 95%CI [−0.20, 1.74], p=0.120, d=0.26).

Hazardous Alcohol Use (AUDIT-C).

For hazardous alcohol use (RMSEA=0.08, CFI=0.96, TLI=0.93, SRMR=0.06), condition was not a statistically significant predictor of the intercept (β=0.04, 95%CI [−0.13, 0.21], p=0.642) or the first segment of slope (screening to baseline; β=0.02, 95%CI [−0.21, 0.24], p=0.896). However, condition was a statistically significant predictor of the second segment of slope (baseline to three month follow-up; β=−0.32, 95%CI [−0.61, −0.03], p=0.030, d=0.37). Indeed, the decline in hazardous alcohol use was larger among the PFI group from baseline to three month follow-up (β=−1.47, 95%CI [−2.03, −0.90], p<0.001, d=−0.61), relative to control (β=−0.65, 95%CI [−1.07, −0.24], p=0.002, d=−0.54).

Anxiety Sensitivity (ASI-3).

Condition was not a statistically significant predictor of anxiety sensitivity intercept (RMSEA=0.05, CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, SRMR=0.05; β=−0.02, 95%CI [−0.27, 0.22], p=0.863) or the first segment of slope (screening to baseline; β=0.38, 95%CI [−1.06, 1.82], p=0.608). However, condition was a statistically significant predictor of the second segment of slope (baseline to three month follow-up; β=−0.55, 95%CI [−0.98, −0.12], p=0.011, d=0.19). Anxiety sensitivity declined to a larger degree in the PFI group (β=−2.62, 95%CI [−3.70, −1.55], p<0.001, d=−0.53) than in control (β=−1.25, 95%CI [−2.19, −0.32], p=0.009, d=−0.39) from baseline to three month follow-up.

Emotional Symptoms (MASQ)3.

In the model for anxiety (RMSEA=0.03, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, SRMR=0.06), condition was not a statistically significant predictor of intercept (β=0.10, 95%CI [−0.11, 0.30], p=0.350) or slope (β=−0.16, 95%CI [−0.60, 0.28], p=0.478, d=0.16). Condition was not a statistically significant predictor of depression intercept (RMSEA<0.01, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.05; β=−0.02, 95%CI [−0.21, 0.18], p=0.877) or slope (β=0.15, 95%CI [−0.33, 0.63], p=0.539, d=0.20).

Negative Reinforcement Drinking Motives (DMQ).

For drinking to cope with anxiety (RMSEA=0.10, CFI=0.93, TLI=0.88, SRMR=0.12) condition was not a statistically significant predictor of intercept (β=0.08, 95%CI [−0.09, 0.25], p=0.370) or slope (β=0.16, 95%CI [−0.04, 0.36], p=0.112, d=0.04). For drinking to cope with depression (RMSEA=0.09, CFI=0.95, TLI=0.91, SRMR=0.08) condition was not a statistically significant predictor of intercept (β=0.17, 95%CI [−0.01, 0.34], p=0.055) or slope (β=0.03, 95%CI [−0.17, 0.23], p=0.761, d=0.06). Finally, condition was not a statistically significant predictor of intercept (RMSEA<0.01, CFI>0.99, TLI>0.99, SRMR=0.05; β=0.01, 95%CI [−0.17, 0.18], p=0.988) or slope (β=0.12, 95%CI [−0.08, 0.33], p=0.237, d=0.001) for drinking to conform.

Discussion

The current study examined the development of an integrated PFI for hazardous drinkers with elevated anxiety sensitivity. The intervention was remotely-delivered, utilizing a well-established PFI framework for alcohol (mis)use (Walters & Neighbors, 2005) augmented with anxiety sensitivity education and reduction techniques (e.g., Keough & Schmidt, 2012) and applied among emotionally vulnerable hazardous drinking college students. Data suggest that the intervention was feasible to administer remotely and that it was rated as more acceptable than an attention control. Results of a pilot RCT with three month follow-up favored the integrated condition with regard to primary outcomes (motivation to change alcohol use, hazardous alcohol use, and anxiety sensitivity). Overall, these findings support hypotheses that the novel integrated PFI would be feasible to deliver, perceived as acceptable in this population, and merit future larger-scale efficacy trials due to encouraging pilot outcomes in terms of both effect size and statistical significance despite the relatively small sample. Evidence of even a signal of an effect in this low-cost remotely delivered intervention is encouraging for future efforts to develop cheap, widely accessible interventions for potentially at-risk students.

Successful enrollment (Figure 1) suggests that it was feasible to recruit hazardous drinking college students with elevated anxiety sensitivity, consistent with evidence that a majority of hazardous drinking college students have elevated anxiety sensitivity levels (Paulus & Zvolensky, 2020). Furthermore, it was feasible to administer the intervention remotely and to retain participants through three months of remotely-delivered follow-up assessments; the current study preserved 67.2% through three months, similar to a recent web-based PFI that retained 68% of college drinkers through one month (Young & Neighbors, 2019). Having comparable retention rates to past work is encouraging, particularly given the current sample consisted of a severe group (i.e., hazardous drinkers with co-occurring emotional vulnerabilities); such samples have previously indicated a lack of interest in treatment for alcohol (mis)use (Capron et al., 2018). Importantly, attrition was not statistically different between conditions at any follow-up (trivial effect sizes) suggesting that outcomes were not biased by differential attrition. Future work should nevertheless examine ways to improve retention over time in remotely-delivered interventions given one third were not reached at three month follow-up. However, retention appears to be a challenge for remotely-delivered interventions broadly, rather than one specifically related to this study.

Participants in the integrated PFI condition provided significantly greater acceptability ratings, than in the control (medium to large effect sizes). Such ratings are essential to effective treatments (Kazdin, 2000). Thus, there is preliminary evidence that the integrated PFI was well received by this sample of emotionally vulnerable hazardous drinking students. Since the intervention consists of a single session with computer-delivered prompts, many of the interpersonal factors (e.g., therapeutic alliance) central in face-to-face therapy (Flückiger et al., 2018) are not present. As such, it is important for computer-based interventions to assure that individuals are instilled with positive expectations (e.g., hope) in order to make changes in their behavior (Gallagher et al., 2020). Of note, participation in the current study did not necessitate willingness or desire to change in any way, making the findings regarding anticipated change particularly remarkable. Nevertheless, acceptability ratings observed in the integrated PFI group could indicate that expectancy effects are accounting for some of the improvements relative to control. Future work should compare the outcomes of an integrated PFI to a control condition with similar perceived acceptability.

Regarding primary outcomes, the integrated PFI group had significantly increased motivation to change alcohol use whereas no significant change was observed in the control, consistent with past work (Murphy et al., 2010). Again, this is relevant given participants did not have to be motivated at all to change their alcohol use in order to participate. The increase in motivation observed in the integrated PFI group was moderate (Table 2; d=0.48) with most of the change occurring early on (between baseline and one-week follow-up) with trivial changes thereafter. The intervention appears to have had a quick impact on motivation that did not meaningfully deteriorate over the three month follow-up. Conversely, in the control, there was a small (non-significant) increase in motivation (d=0.26), with most of that change occurring between one month and three month follow-up; it is unclear from the current findings whether any meaningful factor(s) may have led to the improvement in motivation between these follow-ups in the control or if it was an artifact of the small pilot sample.

In terms of hazardous alcohol consumption, reduction in the integrated PFI group was significantly greater and of a larger effect size (d=−0.61) than control (d=−0.54) from baseline to three month follow-up. The integrated PFI group demonstrated twice the reduction as control from baseline to week one follow-up and from month one to month three follow-up. These findings are notable in light of past work demonstrating a lack of effect of computer-based PFI for reducing alcohol (mis)use among hazardous drinkers (Baumann et al., 2018). Ostensibly, the current intervention was able to reduce hazardous alcohol consumption among hazardous drinkers due to the inclusion of anxiety sensitivity reduction techniques in addition to the standard (i.e., alcohol-only) PFI approach. Indeed, the reduction of anxiety sensitivity alone has been associated with reduced alcohol (mis)use (Olthuis et al., 2015; Paulus et al., 2019; Watt et al., 2006; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2018). The significant, albeit smaller, alcohol reduction in the control group was not surprising, as previous PFI trials have documented significant alcohol consumption declines in attention controls (Young & Neighbors, 2019). It is likely that the repeated assessment of alcohol use over time can act as a low level intervention, as it draws individuals’ attention to their own drinking (Clifford & Maisto, 2000). Indeed, self-monitoring of behavior is a well-established component of many efficacious interventions (Carter et al., 2007).

As anticipated, the integrated PFI group evidenced a statistically significant decline in anxiety sensitivity that was larger than that observed in controls. Importantly, both groups demonstrated substantial declines in anxiety sensitivity from screening to baseline (d’s= −0.61 to −0.41), which is consistent with a tendency for anxiety sensitivity to naturally decline over multiple measurement occasions, whether or not an intervention has been delivered (Broman-Fulks et al., 2009). The availability of two pre-intervention measurements (screening and baseline) provided a multiple baseline, allowing anxiety sensitivity to stabilize somewhat before evaluating changes associated with condition. Indeed, after accounting for the initial sizable decline with the first slope segment (screening to baseline), the integrated PFI group exhibited greater decline from baseline to week one with greater than four times the reduction from week one to month one, relative to control (Table 2). Both groups experienced similar small declines thereafter. Examining total change from baseline to month-three (i.e., after accounting for change between screening and baseline), the integrated PFI reduced to a medium degree (d=−0.53) compared to small reduction for control (d=−0.39).

Although not statistically significantly different, examination of effect sizes indicated that anxiety symptoms evidenced a small decline in the integrated PFI (d=−0.25), which was twice the amount observed in control (d=−0.12). The decline in anxiety primarily occurred between the last two follow-ups in the integrated PFI group, which was after the majority of anxiety sensitivity reduction (i.e., by month one follow-up). Given change in anxiety sensitivity may drive subsequent change in emotional symptoms (Gallagher et al., 2013; Olthuis et al., 2014; Paulus, Brandt, et al., 2020), it is possible that anxiety symptoms may have continued to decline had a longer follow-up period been utilized. Additionally, effects may have been more prominent for physiologically-based anxiety given the strong link between anxiety sensitivity and panic (Paulus et al., 2015; Taylor, 2014). Our anxiety measure may have failed to detect changes in physiological anxiety specifically. Future work could therefore consider assessing multiple facets of anxiety (e.g., cognitive vs. physiological; Steptoe & Kearsley, 1990).

Findings for the remaining secondary outcomes (depression, negative reinforcement motives) were less encouraging with no statistically significant effects of condition on trajectories. There was trivial change in depression symptoms in both groups (d’s=−0.14–0.06), consistent with a previous anxiety sensitivity-baed intervention (Olthuis et al., 2014). Although anxiety sensitivity is a well-established mechanism underlying anxiety and depression (Naragon-Gainey, 2010), anxiety sensitivity-based interventions may be more efficacious in reducing anxiety than depression (e.g., Norr et al., 2014).

Regarding coping motives, there were similar small reductions across conditions for both drinking to cope with anxiety and drinking to cope with depression. The lack of a finding for drinking to cope with anxiety is particularly unexpected given the intervention discussed psychoeducation for drinking to cope with emotional symptoms and provided alternative coping strategies. Indeed, past work has shown that drinking to cope with anxiety mediated intervention effects on alcohol misuse (Olthuis et al., 2015). One reason for the lack of an effect on either facet of coping motives could be that the current intervention contained only a single one-hour session whereas Olthuis et al. (2015) utilized a comprehensive eight-session intervention including psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, interoceptive exposure, and relapse prevention. Likewise, conformity motives evidenced virtually no change in either group (d’s=0.04). Although drinking to conform has been shown to significantly reduce in an anxiety sensitivity-focused intervention (Watt et al., 2006), that study utilized three 90-minute sessions. Taken together, it appears likely that more intensive dosing of an anxiety sensitivity intervention may be needed to reduce negative reinforcement drinking motives, particularly among affectively vulnerable hazardous drinkers. Indeed, given that symptoms of anxiety and depression did not significantly reduce in the current study, it stands to reason that drinking to cope with such symptoms would not reduce. Future studies may need to utilize a more intensive anxiety sensitivity intervention (e.g., a longer session or multiple sessions) in order for anxiety sensitivity reductions to lead to reductions in emotional symptoms and subsequent reductions in alcohol use to cope with those emotional symptoms (Allan et al., 2015). Additionally, PFIs may consider adding in normative data on drinking motives to create normative discrepancies between one’s own drinking to cope/conform relative to their peers.

These encouraging pilot results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the study was conducted remotely and relied on self-report, which is subject to biases in reporting as well as potentially not attending to the content (Lewis & Neighbors, 2015). For example, there was likely variability regarding the degree to which participants practiced anxiety sensitivity reduction tactics in the videos. Future integrated PFIs could consider adding elements of a game into the intervention (e.g., Boyle et al., 2017) to enhance engagement and/or using webcams for researchers to document participation levels. Second, although diverse in terms of race/ethnicity the study consisted of primarily female participants, as in past work (e.g., Young & Neighbors, 2019). Nevertheless, analyses controlled for demographic factors of age, sex, and racial/ethnic minority status (Table 3). Third, given the preliminary nature of the study, the comparison condition was limited to an attention control. Future work should evaluate the efficacy of the integrated PFI to an alcohol-only PFI as well as a (non-alcohol) anxiety sensitivity reduction intervention (e.g., Olthuis et al., 2015; Watt et al., 2006) to examine the relative benefit of integrating PFI for hazardous drinking with anxiety sensitivity reduction. Future work may also examine which components of the intervention (e.g., psychoeducation vs. normative discrepancies) are most effective in improving various outcomes and whether ordering of intervention components has a meaningful effect on outcomes. Fourth, hazardous drinkers were selected based on established AUDIT cut-offs (Saunders et al., 1993). However, the AUDIT assesses past-year drinking and is not appropriate for repeated measures in the current study timeframe. The AUDIT-C was used for repeated measures of hazardous alcohol consumption (Reinert & Allen, 2007); yet, AUDIT-C lacks detail regarding alcohol problems/consequences, which should be evaluated in future work. Fifth, some researchers (DeMartini & Carey, 2012) have recommended raising AUDIT cut-offs for college students. Although this can have the added benefit of increasing specificity for hazardous drinking, it may unnecessarily exclude individuals who are engaging in unhealthy (hazardous) alcohol use. Given research that there is no safe amount of alcohol consumption (Griswold et al., 2018) in concert with the growing normalization of hazardous drinking in college culture (Wechsler & Nelson, 2001) screening and brief intervention should be provided broadly, particularly with low level single-session computerized interventions. Furthermore, PFIs have been used in among relatively light drinking college students (Dotson et al., 2015) with no known adverse effects. Future work should nevertheless evaluate the current intervention among across the spectrum of alcohol misuse, including among those with AUD. Sixth, the current study did not formally assess diagnoses and cannot speak to AUD or emotional disorder diagnoses.

Table 3:

Covariate associations from latent growth curve models

| Age | Sex | Minority Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope-1 | Slope-2 | Intercept | Slope-1 | Slope-2 | Intercept | Slope-1 | Slope-2 | |

| AL | 0.29* | −0.34 | - | 0.002 | −0.60* | - | 0.10 | 0.01 | - |

| [0.08, 0.49] | [−0.85, 0.18] | [−0.21, 0.21] | [−1.15, −0.06] | [−0.11, 0.31] | [−0.52, 0.54] | ||||

| AUDIT-C | 0.12 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.22* | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.04 | −0.23 | 0.13 |

| [−0.05, 0.30] | [−0.40, 0.06] | [−0.33, 0.29] | [−0.39, −0.06] | [−0.15, 0.30] | [−0.16, 0.48] | [−0.21, 0.14] | [−0.46, 0.01] | [−0.20, 0.46] | |

| ASI-3 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 2.79* | −0.11 | 0.17 | 0.34 | −0.59 |

| [−0.29, 0.22] | [−1.78, 1.91] | [−0.62, 0.59] | [−0.28, 0.22] | [0.94, 4.65] | [−0.75, 0.54] | [−0.08, 0.42] | [−1.51, 2.19] | [−1.23, 0.06] | |

| MASQ-A | −0.05 | −0.24 | - | 0.06 | −0.24 | - | 0.10 | −0.01 | - |

| [−0.26, 0.16] | [−0.66, 0.18] | [−0.14, 0.27] | [−0.69, 0.21] | [−0.11, 0.31] | [−0.47, 0.45] | ||||

| MASQ-D | 0.02 | 0.03 | - | 0.14 | −0.22 | - | −0.05 | −0.08 | - |

| [−0.18, 0.22] | [−0.43, 0.49] | [−0.05, 0.33] | [−0.72, 0.27] | [−0.25, 0.15] | [−0.57, 0.42] | ||||

| DMQ-A | 0.01 | −0.17 | - | 0.02 | 0.06 | - | −0.17 | −0.03 | - |

| [−0.18, 0.19] | [−0.42, 0.08] | [−0.16, 0.21] | [−0.20, 0.33] | [−0.35, 0.02] | [−0.30, 0.24] | ||||

| DMQ-D | 0.07 | −0.21 | - | 0.09 | −0.18 | - | 0.01 | −0.11 | - |

| [−0.11, 0.26] | [−0.43, 0.01] | [−0.09, 0.27] | [−0.41, 0.06] | [−0.18, 0.19] | [−0.35, 0.13] | ||||

| DMQ-C | −0.06 | −0.03 | - | 0.08 | −0.16 | - | −0.01 | −0.01 | - |

| [−0.24, 0.12] | [−0.23, 0.17] | [−0.10, 0.26] | [−0.37, 0.05] | [−0.19, 0.17] | [−0.22, 0.21] | ||||

Notes: Notes: AL=Alcohol Ladder; AUDIT-C=Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption; ASI-3=Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; MASQ=Mood Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; MASQ-A=Anxiety Subscale; MASQ-D=Depression Subscale; DMQ=Drinking Motives Questionnaire; DMQ-A=Anxiety Coping Subscale; DMQ-D=Depression Coping Subscale; DMQ-C=Conformity Subscale; Age=Participant Age; Sex=Female (1); Male (0); Minority Status=Racial/Ethnic Minority (1); White (0); Intercept=Model Intercept; Slope-1=Model Slope (for AUDIT-C and ASI-3 Slope-1 represents the Slope from screening to baseline; for all other measures Slope-1 represents the total Slope); Slope-2=Model Slope from baseline to three month follow-up for AUDIT-C and ASI-3. Standardized effects and 95% Confidence Intervals are presented.

p<0.05

Finally, the study represents an initial test of a novel integrated PFI. As such, there is a relatively small sample size, with effect size emphasized. For clinical trial development, highlighting effect size rather than statistical significance may offer more practical benefits, particularly in the case of limited efficacy trials (e.g., Bowen et al., 2009). It is difficult to detect statistically significant effects in small sample sizes. Moreover, this novel PFI consisted of one session and is expected to yield relatively small effect sizes, consistent with past meta-analytic work (Dotson et al., 2015). The study was also administered remotely, which can suppress the potency of PFIs, relative to in-person versions (Rodriguez et al., 2015). Prior to rolling out a large-scale RCT of several hundred participants (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2019), one can conduct a pilot feasibility study and compare the effect sizes to past work, particularly in the case of PFIs where there are many benchmarks for effect size (Dotson et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2013). Furthermore, effect sizes are useful for meta-analyses, whereas p-values offer no additional information (Borenstein et al., 2011). Interpreting outcomes based on whether significance thresholds were met can be misleading (McShane et al., 2019). For example, there was no statistically significant effect on anxiety symptoms, yet, based on effect sizes, there appears to have been a small but potentially meaningful change among the integrated PFI but not control. By focusing on effect size, a clearer pattern can be observed. Beyond ‘rules of thumb’, effect sizes that are ‘small’ (e.g., d=0.2) can be considered large in certain contexts (Kraemer & Kupfer, 2006). In the case of a remotely-delivered integrated PFI that could potentially reach a large number of individuals who otherwise might receive no intervention at all, with little to no implementation costs, even a small effect can be quite impactful from a public health standpoint (Dotson et al., 2015).

The findings of this study demonstrate the promise of this novel remotely-delivered computerized integrated PFI in a small RCT. The sample included hazardous drinking students with elevated anxiety sensitivity and jointly targeted both drinking and anxiety sensitivity. The intervention was feasible to implement and participants rated the integrated PFI as highly acceptable. Relative to control, there were statistically significant differences in regards to improvements in motivation to change alcohol use, hazardous alcohol use, and anxiety sensitivity. Effect sizes suggest that the integrated PFI group also evidenced meaningful changes in anxiety symptoms. There was no advantage of the intervention in terms of depression symptoms or negative reinforcement drinking motives (drinking to cope with depression/anxiety or drinking to conform). The current findings highlight the promise of the first integrated anxiety sensitivity-alcohol intervention. Furthermore, this report is the first documented use of PFI to reduce drinking in emotionally vulnerable (i.e., high-anxiety sensitivity) drinkers. If replicated with a larger sample and with a stronger active control condition, this intervention may represent a low-cost, widely disseminable intervention for high-risk drinkers such as those with emotional vulnerabilities.

Highlights.

Novel computerized personalized feedback intervention (PFI)

PFI was augmented with anxiety sensitivity (AS) reduction

The intervention was feasible to administer and acceptable

Relative to attention control, PFI had improved outcomes

Motivation, hazardous alcohol use, and AS improved

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIAAA grant (F31 AA 024968) awarded to the first author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Five participants were removed for answering two or more quality control questions incorrectly. In addition, all five individuals displayed obvious patterns of random/inattentive responding (e.g., selecting the first response option for all items of all measures).

Unadjusted models were also run (i.e., without covariates). The pattern of findings did not change and can be obtained from the first author.

Linear models were fit for MASQ-A and MASQ-D due to lack of convergence.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- Allan NP, Albanese BJ, Norr AM, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2015). Effects of anxiety sensitivity on alcohol problems: evaluating chained mediation through generalized anxiety, depression and drinking motives. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 110(2), 260–268. 10.1111/add.12739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Korte KJ, Capron DW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2014). Factor mixture modeling of anxiety sensitivity: A three-class structure. Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 1184–1195. 10.1037/a0037436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD (2003). Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 545. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva. World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Thornton LK, Hiles S, Hides L, & Lubman DI (2012). Psychological interventions for alcohol misuse among people with co-occurring depression or anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 139(3), 217–229. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann S, Gaertner B, Haberecht K, Bischof G, John U, & Freyer-Adam J (2018). How alcohol use problem severity affects the outcome of brief intervention delivered in-person versus through computer-generated feedback letters. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 82–88. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black N, Mullan B, & Sharpe L (2016). Computer-delivered interventions for reducing alcohol consumption: meta-analysis and meta-regression using behaviour change techniques and theory. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S-M, & Olfson M (2008). Mental health of college students and their non–college-attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, & Rothstein HR (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Farchione TJ, Sauer-Zavala S, Murray HW, Fortune MR, & Barlow DH (2013). Anxiety sensitivity and interoceptive exposure: A transdiagnostic construct and change strategy. Behavior Therapy, 44(3), 417–431. 10.1016/j.beth.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, Bakken S, Kaplan CP, Squiers L, & Fabrizio C (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle SC, Earle AM, LaBrie JW, & Smith DJ (2017). PNF 2.0? Initial evidence that gamification can increase the efficacy of brief, web-based personalized normative feedback alcohol interventions. Addictive Behaviors, 67, 8–17. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brière FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, & Lewinsohn PM (2014). Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 526–533. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman-Fulks JJ, Berman ME, Martin HM, Marsic A, & Harris JA (2009). Phenomenon of declining anxiety sensitivity scores: a controlled investigation. Depression and Anxiety, 26(1), E1–E9. 10.1002/da.20436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, & Mancill RB (2001). Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 585. 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron DW, Bauer BW, Madson MB, & Schmidt NB (2018). Treatment Seeking among College Students with Comorbid Hazardous Drinking and Elevated Mood/Anxiety Symptoms. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(6), 1041–1050. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1392982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Day SX, Cinciripini PM, & Wetter DW (2007). Momentary health interventions: Where are we and where are we going. The Science of Real-Time Data Capture. Self Reports in Health Research, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Clair M, Stein L. a. R., Martin R, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Monti PM, Golembeske C, & Lebeau R (2011). Motivation to change alcohol use and treatment engagement in incarcerated youth. Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 674–680. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, & Maisto SA (2000). Subject reactivity effects and alcohol treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(6), 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- CORE Institute. (2015). CORE Alcohol and Drug Survey https://core.siu.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, & Breslin FC (2004). Only one in three people with alcohol abuse or dependence ever seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 221–223. 10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00077-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, Batt-Rawden S, Greenberg N, Wessely S, & Goodwin L (2014). A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(9), 1401–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Santomauro D, Erskine H, Mantilla-Herrara A, Whiteford H, Leung J, Naghavi M, & Griswold M (2018). The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(12), 987–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, & Carey KB (2009). Correlates of AUDIT Risk Status for Male and Female College Students. Journal of American College Health, 58(3), 233. 10.1080/07448480903295342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, & Carey KB (2011). The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 169–177. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, & Carey KB (2012). Optimizing the use of the AUDIT for alcohol screening in college students. Psychological Assessment, 24(4), 954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, & Borkovec TD (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(2), 73–86. 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, & Bowers CA (2015). Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PloS One, 10(10), e0139518. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle SR, Donovan DM, & Kivlahan DR (2007). The factor structure of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(3), 474–479. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, & Gollust SE (2007). Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care, 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbey FM, Claus E, Audette AR, Niculescu M, Banich MT, Tanabe J, Du YP, & Hutchison KE (2008). Exposure to the taste of alcohol elicits activation of the mesocorticolimbic neurocircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(6), 1391. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, & Horvath AO (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316. 10.1037/pst0000172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Long LJ, Richardson A, D’Souza J, Boswell JF, Farchione TJ, & Barlow DH (2020). Examining hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism of change across anxiety disorders and CBT treatment protocols. Behavior Therapy, 51(1), 190–202. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Naragon-Gainey K, & Brown TA (2014). Perceived control is a transdiagnostic predictor of cognitive-behavior therapy outcome for anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(1), 10–22. 10.1007/s10608-013-9587-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Payne LA, White KS, Shear KM, Woods SW, Gorman JM, & Barlow DH (2013). Mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder: The unique effects of self-efficacy and anxiety sensitivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(11), 767–777. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Neighbors C, & Larimer ME (2006). A randomized clinical trial of a brief, mailed intervention for symptoms of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 393–399. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Varvil-Weld L, Mittmann AJ, Mallett K, & Turrisi R (2015). Brief web-based intervention for college students with comorbid risky alcohol use and depressed mood: does it work and for whom? Addictive Behaviors, 42, 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Williams LM, & Humphreys K (2016). A trans-diagnostic review of anxiety disorder comorbidity and the impact of multiple exclusion criteria on studying clinical outcomes in anxiety disorders. Translational Psychiatry, 6(6), e847–e847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Jung J, Zhang H, Fan A, & others. (2017). Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, & Hasin DS (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, & Conrod PJ (2007). Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire--Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors, 32(11), 2611–2632. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SR, Tymeson HD, Venkateswaran V, Tapp AD, Forouzanfar MH, & Salama JS (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 392(10152), 1015–1035. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman BT (2016). Performance of the AUDIT in Detecting DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders in College Students. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(11), 1521–1528. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1188949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, & Grant BF (2004). The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(9), 891–896. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, & Smyth D (2017). Magnitude and Trends in Heavy Episodic Drinking, Alcohol-Impaired Driving, and Alcohol-Related Mortality and Overdose Hospitalizations Among Emerging Adults of College Ages 18–24 in the United States, 1998–2014. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(4), 540–548. 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, & Morgenstern J (2010). Validation of a contemplation ladder in an adult substance use disorder sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(1), 137–144. 10.1037/a0017895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin C, Paulus DJ, Garey L, Kauffman B, Bakhshaie J, Manning K, Mayorga NA, & Zvolensky MJ (2018). Towards a greater understanding of anxiety sensitivity across groups: The construct validity of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychiatry Research, 268, 72–81. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HS, Park S, Lim SM, Ma J, Kang I, Kim J, Kim E-J, Choi YJ, Lim J, Chung Y-A, Lyoo IK, Yoon S, & Kim JE (2017). Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) in Public First Responders. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(8), 1069–1075. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1271986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Miech RA (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–55 [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Garnett C, Crane D, Brown J, Muirhead C, Redmore J, O’Donnell A, Newham JJ, Vocht F. de, Hickman M, Brown H, Maniatopoulos G, & Michie S (2017). Personalised digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community-dwelling populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9. 10.1002/14651858.CD011479.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2000). Perceived barriers to treatment participation and treatment acceptability among antisocial children and their families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9(2), 157–174. 10.1023/A:1009414904228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keough ME, & Schmidt NB (2012). Refinement of a brief anxiety sensitivity reduction intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 766–772. 10.1037/a0027961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Young KE, Caniglia EC, Fiellin DA, Maisto SA, Marshall BDL, Edelman EJ, Gaither JR, Chichetto NE, Tate J, Bryant KJ, Severe M, Stevens ER, Justice A, & Braithwaite SR (2020). Association of Alcohol Screening Scores With Adverse Mental Health Conditions and Substance Use Among US Adults. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e200895–e200895. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, & Kupfer DJ (2006). Size of Treatment Effects and Their Importance to Clinical Research and Practice. Biological Psychiatry, 59(11), 990–996. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, & Borchardt C (2000). The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 149–171. 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai HMX, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, & Hunt GE (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, & Zvolensky MJ (2015). Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: A transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion–smoking comorbidity. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 176–212. 10.1037/bul0000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, & Neighbors C (2015). An examination of college student activities and attentiveness during a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 162. 10.1037/adb0000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis SAGE publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Kraemer K, & Kelley ME (2000). An empirical investigation of the factor structure of the AUDIT. Psychological Assessment, 12(3), 346–353. 10.1037/1040-3590.12.3.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane BB, Gal D, Gelman A, Robert C, & Tackett JL (2019). Abandon statistical significance. The American Statistician, 73(sup1), 235–245. 10.1080/00031305.2018.1527253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, & Carey KB (2016). Drinking over the lifespan: Focus on college ages. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(1), 103–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Hall N, DiBello AM, Park CJ, Freeman L, Meier E, Leavens ELS, & Leffingwell TR (2020). Depressive symptoms as a moderator of college student response to computerized alcohol intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 115, 108038. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Leffingwell T, Claborn K, Meier E, Walters S, & Neighbors C (2013). Personalized feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: An update of Walters & Neighbors (2005). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 909–920. 10.1037/a0031174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB, & DeShon RP (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 105. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, & McDevitt-Murphy ME (2010). Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: Impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K (2010). Meta-analysis of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to the depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 128–150. 10.1037/a0018055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, DiBello AM, Young CM, Steers M-LN, Rinker DV, Rodriguez LM, Knee CR, Blanton H, & Lewis MA (2019). Personalized normative feedback for heavy drinking: An application of deviance regulation theory. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 115, 73–82. 10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, & Lewis MA (2004). Targeting Misperceptions of Descriptive Drinking Norms: Efficacy of a Computer-Delivered Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 434–447. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norr AM, Allan NP, Macatee RJ, Keough ME, & Schmidt NB (2014). The effects of an anxiety sensitivity intervention on anxiety, depression, and worry: mediation through affect tolerances. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 59, 12–19. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, & Paulus DJ (2016). Toward a Unified Treatment for Emotional Disorders: Update on the Science and Practice. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 854–868. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, & Paulus DJ (2017). Transdiagnostic models of anxiety disorder: Theoretical and empirical underpinnings. Clinical Psychology Review 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, & Wolitzky-Taylor KB (2009). Anxiety sensitivity and the anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 974–999. 10.1037/a0017428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Mackinnon SP, & Stewart SH (2014). Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for high anxiety sensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1005–1022. 10.1037/a0037027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Mackinnon SP, & Stewart SH (2015). CBT for high anxiety sensitivity: alcohol outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 46, 19–24. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Brandt CP, Lemaire C, & Zvolensky MJ (2020). Trajectory of change in anxiety sensitivity in relation to anxiety, depression, and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS following transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(2), 149–163. 10.1080/16506073.2019.1621929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Gallagher MW, Neighbors C, & Zvolensky MJ (2020). Computer-delivered personalized feedback intervention for hazardous drinkers with elevated anxiety sensitivity: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Health Psychology, 1359105320909858. 10.1177/1359105320909858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]