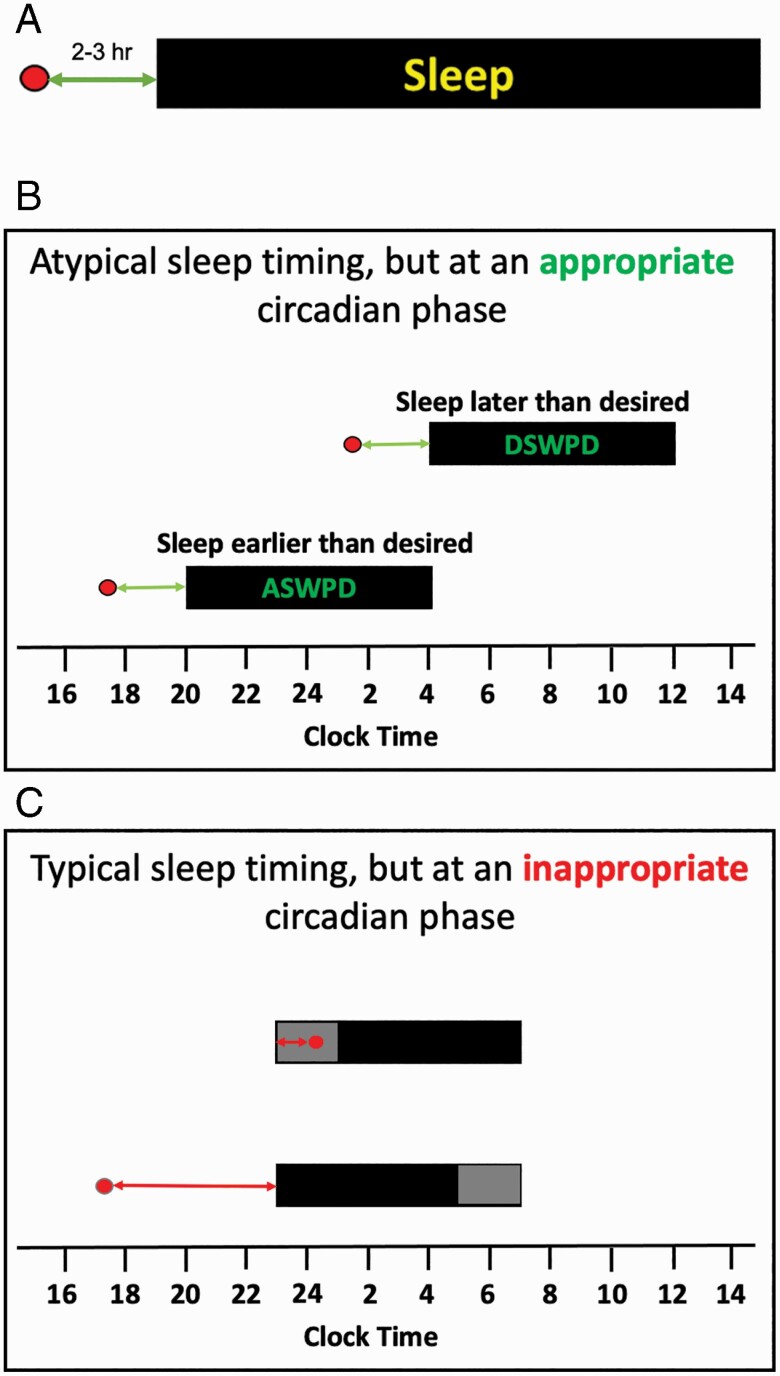

Figure 2.

Relationship between the timing of the circadian phase of the DLMO and the timing of the nocturnal sleep episode. For all panels, the x-axis represents time; DLMO phase is indicated by the red circle; the grey bar represents time in bed, and the black bar represents sleep. (A) Typical phase relationship (in postpubertal adolescents and adults). (B) Circadian rhythm sleep–wake phase disorders are assumed to be caused by an “early” (in the case of ASWPD) or “late” (in DSWPD) “circadian phase timing” which in turn results in sleep occurring earlier or later than desired. In the cases illustrated here, the relative timing between the circadian phase of DLMO (red circle) and sleep onset is appropriate (i.e. sleep occurs at an appropriate circadian time), but the clock time at which each occurs is inappropriate (see also Figure 3, A). (C) Circadian rhythm sleep–wake phase disorders can also arise when the “relative timing” between the underlying rhythm of sleep–wake propensity is “inappropriately aligned relative to” the timing of sleep. This can occur even if time in bed is at a conventional/desired time. This may result in a prolonged sleep latency (indicated by the gray shading at the beginning of scheduled sleep in the upper sleep bar) or early morning awakening (indicated by the gray shading at the end of the sleep episode in the lower bar; see also Figure 3, B and C).