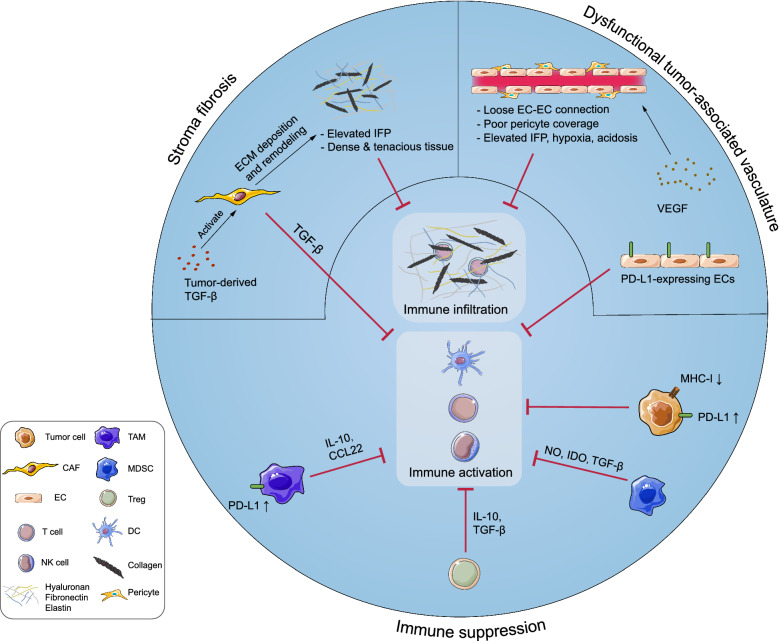

Fig. 1.

Components of tumor microenvironment (TME) contribute to the immunosuppression in various manners. Tumor cells downregulate expression of major histocompatibility complex-I (MHC-I) and antigens to avoid antigen presentation and T cell recognition, and express immune checkpoint proteins such as programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) to inactivate infiltrated T cells. Additionally, tumor cells recruit various immunosuppressive cells [e.g. myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and regulatory-T cells (Tregs)] by expressing immunosuppressive molecules [e.g. interleukin (IL)-10, chemokine ligand (CCL)-5, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β)]. Tumor cells, immunosuppressive cells and various immunoregulatory molecules [e.g. reactive oxygen species (ROS), arginase-1 (Arg-1), CCL-22, IL-10, and PD-L1] construct an immunosuppressive network in the TME. The activities of dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and other immune cells are therefore repressed severely. Moreover, classical stromal components contribute to immunosuppression. Continuous release of tumor-derived vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) leads to the formation of dysfunctional blood vessels with loose endothelial cell (EC)-EC connections and poor pericyte coverage, which exacerbates hypoxia and acidosis in the TME, thereby impairing the functionality of immune cells. Activated cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) lead to excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, which results in dense and tenacious fibrotic tissue surrounding the tumor mass and an elevated interstitial fluid pressure (IFP). These formidable physical barriers severely hinder immune infiltration and drug perfusion