Abstract

Oil and gas exploration in the Arctic can result in the release of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) into relatively pristine environments. Following the recent spill of approximately 17 500 tonnes of diesel fuel in Norilsk, Russia, May 2020, our study focussed on the effects of phenanthrene, a low molecular weight PAH found in diesel and crude oil, on the isolated atrial and ventricular myocytes from the heart of the polar teleost, the Navaga cod (Eleginus nawaga). Acute exposure to phenanthrene in navaga cardiomyocytes caused significant action potential (AP) prolongation, confirming the proarrhythmic effects of this pollutant. We show AP prolongation was due to potent inhibition of the main repolarising current, IKr, with an IC50 value of ~2 µM. We also show a potent inhibitory effect (~55%) of 1 µM phenanthrene on the transient IKr currents that protects the heart from early-after-depolarizations and arrhythmias. These data, along with more minor effects on inward sodium (INa) (~17% inhibition at 10 µM) and calcium (ICa) (~17% inhibition at 30 µM) currents, and no effects on inward rectifier (IK1 and IKAch) currents, demonstrate the cardiotoxic effects exerted by phenanthrene on the atrium and ventricle of navaga cod. Moreover, we report the first data that we are aware of on the impact of phenanthrene on atrial myocyte function in any fish species.

Keywords: Petroleum pollution, Eleginus nawaga, Arctic, White sea, Heart, Cardiotoxicity

1. Introduction

Polar ecosystems are under enormous and immediate threat. The impact of resource overexploitation can act synergistically with climate change to stress polar marine environments. The northern pole is warming at more than 2-times the average global rate (Overland et al., 2017), leading to rapid and significant loss of sea ice, which provides humans longer seasonal access to Arctic waters, dramatically increasing human activities in the region. Activities such as industrial fishing, shipping, foreign species introduction (e.g. attached to ship hauls or in ballast water), and oil and gas exploration are of particular concern (Hasle et al., 2009; Silber and Adams, 2019). Recent years have seen an increase in Arctic oil and gas exploration and extraction activities with many installations taking place within or adjacent to aquatic environments (Wilson, 2017; Keil, 2017). Oil and gas exploration and exploitation damages the environment through dramatic point source spills such as the 1989 devasting Exxon Valdez tanker spill which released 35 000 tonnes of crude oil into the Arctic in Prince William Sound, Alaska; and the 1994 spills in Usinsk, Republic of Komi, on the edge of the polar circle, where more than 60 000 tonnes of oil were released into the tundra and into watercourses which empty into the Barents Sea. More recently, in May 2020, a diesel fuel storage tank collapsed in Norilsk, Russia, releasing approximately 17 500 tonnes of diesel oil into rivers which flow to the Kara Sea. In both the Komi and Norilsk spills, some of the oil was prevented from reaching the oceans but the ongoing risk of human oil exploration in these areas is readily apparent and there are concerns that pollutants frozen in tundra from such events will be released and become bioavailable as Arctic warming continues (Krupenio et al., 1995). In addition to the impacts of catastrophic point spills, oil and gas exploration in the polar regions also causes chronic leaks into the environment which are often larger than point spills in cumulative magnitude. These arise from infrastructure failure and operational construction (e.g. platforms, pipelines, storage, buildings), discharges of waste associated with drilling, discharges of dissolved oils/produced water from wells, and discharges from ships, platforms and sewage (AMAP, 2019). Finally, the unique geographic and climatic characteristics of the Arctic make it a ‘sink’ for pollutants transported into the region from distant sources (AMAP, 2017). Thus, knowledge of the impact of pollutants on Arctic species is paramount for protecting and mitigating against these anthropogenic ecosystem impacts.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are one of the major components of crude oil and previous studies have reported a suite of negative consequences of exposure to PAHs in marine fishes. These include developmental abnormalities, increased mortality, delayed hatching, negatively impacted swimming (Le Bihanic et al., 2014), pericardial and yolk sac oedema, jaw reduction/malformation, and skeletal defects such as lordosis and scoliosis (Lucas et al., 2014). In addition, specific effects on the cardiovascular system have been consistently reported following crude oil exposure in fishes (Incardona et al., 2004; Incardona et al., 2005; Incardona et al., 2009; Adeyemo et al., 2015). Recently, a suite of studies (Incardona et al., 2004; Incardona, 2017; Incardona et al., 2006) suggested low-molecular weight tricyclic PAHs such as phenanthrene (C14H10) are largely responsible for the cardiotoxicity associated with crude oil exposure in fishes (Incardona et al., 2004; Incardona, 2017; Incardona et al., 2006; Brette et al., 2014; Brette et al., 2017; Rigaud et al., 2020a,b). Importantly, Incardona et al. (2004) used embryonic zebrafish to demonstrate phenanthrene acts directly on the contractile and electrical activity of the heart, rather than via downstream activation of detoxification pathways such as those mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Incardona et al., 2004). Weathering (churning/mixing of oiled water) has been shown to increase percentage composition of phenanthrene in the mixture and that has resulted in greater cardiotoxic effects in fishes (Brette et al., 2014; Carls et al., 1999) .

Our mechanistic understanding of these processes was significantly advanced with work from Brette et al. (2014, 2017) which showed crude oil and phenanthrene have direct effects on the ion channels and pumps that control the activity of the fish heart. Whole heart electrical excitation and muscle contraction is controlled by a process known as excitation-contraction coupling in the heart cells (cardiomyocytes). Phenanthrene depresses contractility by inhibiting cellular Ca2+ cycling in the myocytes. Previous work in marine and freshwater fishes show a reduction in Ca2+ flux across the myocyte membrane and from the internal Ca2+ stores of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Brette et al., 2014, 2017) following phenanthrene exposure. Thus, phenanthrene-induced impairment of cellular Ca2+ flux disrupts contractile function of the cardiomyocytes (Heuer et al., 2019), which impairs the heart (Ainerua et al., 2020a) and reduces cardiac output and blood flow in vivo (Nelson et al., 2016). Phenanthrene also affects the electrical activity of the heart by impacting K+fluxes. Specifically, phenanthrene inhibits the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) carried by erg (ether-a-go-go)-like ion channels which are important for repolarising the heart (Ainerua et al., 2020a, Brette et al., 2017, Heuer et al., 2019, Kompella et al., 2021, Marris et al., 2020a, Vehniäinen et al., 2019). Inhibition of IKr can lead to proarrhythmic phenotypes such as prolongation of the action potential (AP) duration and prolongation of the QT interval of the electrocardiogram (ECG). QT prolongation has been linked to human cardiac failure (Marris et al., 2020a) and thus assessment of compound potency on erg channel activity or IKr current density, is a key component of environmental and pharmacological safety testing strategies (Fermini et al., 2016). Phenanthrene is persistent, bioavailable, can readily penetrate membranes and thus can bioaccumulate over time (Rigaud et al., 2020a,b; Yin et al., 2007; Piazza et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2013). For these reasons, phenanthrene is included in the list of priority pollutants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US, EPA). Despite the clear evidence for phenanthrene cardiotoxicity in fishes, species-specificities do exist (e.g. varied responses in salmonids Ainerua et al., 2020a; Vehniäinen et al., 2019). To date, no studies have investigated the impact of phenanthrene on the ion channels underlying cardiac function in a polar fish species. This is an alarming oversight considering the extent of oil exploration in polar waters and the inevitable leakages that occur in these relatively pristine ecosystems.

Here we investigate the impact of acute phenanthrene exposure on all the major ion currents underlying excitation-contraction coupling in atrial and ventricular myocytes of the Navaga cod (Eleginus nawaga, Walbaum, 1792). Navaga are small fishes (15–35 cm) of the cod family (Gadidae), which are commercially fished for human consumption in Russia (http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/3014/en). They inhabit the relatively shallow and broad shelves of Arctic and subarctic waters of the Barents, White and Kara Seas, from the Kola Bay to the Ob River estuary (http://www.fishbase.org/Summary/SpeciesSummary.php?ID=314&AT=navaga). Navaga are eurythermal fish that spawn in winter in shallow waters close to the ice at sub-zero temperatures, whilst in summer they move off shore where they have a preferred water temperature of about 7 °C but can experience temperatures up to 15 °C (DeVries and Steffensen, 2005). Considering the warming of Arctic waters, previous studies have investigated the thermal plasticity of electrical excitability in navaga hearts (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2017, 2015) and seasonal changes in the expression of the cardiac K+ channels (Hassinen et al., 2014). Thus, navaga are a suitable model for cardiotoxicology as their basic (healthy) electrophysiology is known, and they are living in regions vulnerable to toxicant exposure from oil and gas exploration. We hypothesize that acute exposure to phenanthrene will (1) inhibit repolarising K+ channel currents; and thus (2) cause AP prolongation setting up a proarrhythmic cardiac phenotype; and (3) will depress cellular Ca2+ cycling in atrial and ventricle myocytes which would negatively affect contractility.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

All experiments were performed at the White Sea Biological Station of Lomonosov Moscow State University (Louhi district, Karelia, Russia). Navaga cod (Eleginus navaga) were caught from the Kandalaksha Bay of the White Sea close to the White Sea Biological Station (66°19′50″ N, 33°40′06″ E). There is no oil or gas exploration in this region of the White Sea and the closest industrial town, Kandalaksha, is ~100 km away. Fish (body mass = 86.8 ± 5.9 g, n = 14) were captured by hook and line in the beginning of summer (early June, 2020), when water temperature was 11–13 °C and kept in an aquarium with a continuous flow of seawater (12±1 °C) for 7–10 days before the experiments began. Fish were fed with lugworms (Arenicola marina) every other day. All experiments conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996), the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments and were made with the consent of Bioethical Committee of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

2.2. Drugs

Sodium channels blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) and erg channels blocker E-4031 were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Collagenase type IA, trypsin, phenanthrene, acetylcholine chloride (ACh), calcium channels blocker nifedipine and blocker of inward rectifier channels barium chloride (BaCl2) were all purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Phenanthrene stock (30 mM) was prepared in DMSO and used within 2 days. In all experiments, maximal DMSO in extracellular solution was maintained below 1:1000. In experiments with recording of APs, IKr and INa the effects of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene were studied, while concentrations 3, 10 and 30 µM were selected to study the effects of phenanthrene on ICaL (and on IKAch and IK1, see supplemental).

All experiments are paired with ion currents being measured first in the absence, and then in the presence of phenanthrene, via inclusion in the external solution. Phenathrene effects were registered following stabilization of the response (usually within 3–5 mins). Albeit limited, studies report phenanthrene concentrations of ~200 nM and 3 µM in human blood and tissues, respectively, and show evidence of bioaccumulation in fats (logP [octanol/water] coefficient of ~4.4) (Huang et al., 2016; Camacho et al., 2012). Circulating levels in fishes are not know and thus although we acknowledge the concentrations used are relatively high, they are within the expected range during acute exposure, and are practical for identifying mechanism and for comparison with previous studies on fishes (Brette et al., 2017; Vehniäinen et al., 2019; Marris et al., 2020b; Kompella et al., 2021).

2.3. Isolation of cardiac myocytes

Myocytes were isolated using the standard protocol described previously (Vornanen, 1997). Briefly, fish were stunned by a sharp blow to the head, the spine was cut, and the heart was rapidly excised. The bulbus arteriosus was cannulated and myocytes were isolated by retrograde perfusion of the heart with isolation solution [(mmol L−1): NaCl 100, KCl 10, KH2PO4∙2H2O 1.2, MgSO4∙7H2O 4, taurine 50, glucose 10 and HEPES 10 at pH of 6.9], containing proteolytic enzymes. The concentration of enzymes (collagenase type IA, 0.5 mg ml−1; trypsin type IX, 0.33 mg ml−1; fatty acid free bovine serum albumin, 0.33 mg ml−1) were selected in accordance with earlier studies on navaga (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2017, 2015). Isolated atrial and ventricular myocytes were obtained by mincing and triturating of ventricular and atrial myocardium after 10–12 min of heart perfusion. Atrial and ventricular cells were stored separately up to 8 h at 5 °C in isolation solution.

2.4. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

A small aliquot of myocyte suspension was placed in the experimental chamber (RCP-10T, Dagan, Maryland, MI, USA, volume 150 µL) and superfused at the rate of about 1.5 ml min−1 with external K+-based physiological saline solution containing (in mmol L−1) NaCl 150, KCl 3.5, NaH2PO4 0.4, MgSO4 1.5, CaCl2 1.8, glucose 10 and HEPES 10 at pH 7.6 (adjusted with NaOH). Temperature of the external solution was set to 12 °C using a Peltier device (CL-100, Warner Instruments, USA). Ionic currents were recorded in the voltage-clamp mode of the whole-cell patch-clamp technique using the Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) and WinWCP v.4.8.7 software (University of Strathclyde, UK). Patch pipettes of 1.5–2.5 MΩ resistance were pulled from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, USA). Pipette capacitance, access resistance and whole cell capacitance were routinely compensated.

2.5. Recording solutions

For recording of K+ currents the standard external K+-based physiological solution was used in combination with pipettes filled with K+-based electrode solution containing (in mmol l−1): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP and 10 HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The EGTA concentration in this solution was reduced to 0.025 mmol l−1 when measuring membrane potential in current-clamp mode as it more closely resembles the buffering capacity of fish cytosol (Hove-Madsen and Tort, 1998). For recording of Ca2+ currents, KCl in external solution was substituted with equimolar quantity of CsCl. The pipette solution for measuring Ca2+ currents contained (in mmol l−1): 140 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP and 10 HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The external solution for INa recordings contained less Na+ to reduce the driving force for Na+ influx (in mmol l−1): 20 NaCl, 120 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.7 with CsOH. The pipette solution for INa contained (in mmol l−1): 5 NaCl, 130 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 Mg2ATP, 5 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH (Vornanen et al., 2011). During recordings of K+ currents, the Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (300 nM) and the Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (20 µM) were constantly present in external solution providing complete block (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2017, 2015). During experiments with inward rectifier K+ currents, selective IKr blocker E-4031 (5 µM) was also added to external solution (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2017, 2015). Na+ currents were recorded in the presence of 20 µM nifedipine.

2.6. Voltage protocols

APs were evoked by injection of supra-threshold depolarising current at 0.2 Hz frequency in current-clamp mode in ventricular myocytes only. Electrical activity of navaga atrial myocytes was not investigated, because they are unable to maintain stable resting potential in current-clamp mode due to the tiny density of background inward rectifier current (IK1) and the absence of ACh-dependent inward rectifier current (IKACh) in control conditions (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2015; Hassinen et al., 2014).

Inward rectifier currents, the background IK1 and the acetylcholine-dependent IKACh, were elicited in atrial and ventricular myocytes from the holding potential of −80 mV every 10 s with 1-s repolarising voltage ramps from +60 mV to −120 mV in the absence and presence of 2 mM Ba2+ and 10 µM ACh for IK1 or IKACh, respectively. IK1 was obtained as the Ba2+-sensitive current. IKACh was obtained as the current induced by ACh. During the application of ACh, IKACh reached maximal values during the first 10 s, then started to decline, reaching the stable plateau level after 1 min. Phenanthrene was added after IKACh reached the plateau level.

IKr tail current was elicited by a double-pulse protocol from the holding potential of −80 mV. An initial 2-s depolarization from −80 to +60 mV (in 20 mV steps) was followed by a 2-s repolarization to −20 mV (Vornanen et al., 2002). IKr elicits rapid transient currents in response to extra depolarising stimulus during an AP. This current is protective to cardiac arrhythmia (Vandenberg et al., 2012). IKr transient currents were generated using a paired AP-like voltage-clamp protocol with depolarizing stimuli to 0 mV at increasing intervals (15 ms). IKr transient currents were obtained following each condition (control, 1 µM phenanthrene and 5 µM E-4031) within the same cell. Peak transient currents obtained with E-4031 were subtracted from corresponding currents in both control and phenanthrene exposure. Peak IKr transients for each cell under control conditions were then normalized to the maximal current transient. Peak IKr transients obtained in the presence of 1 μM phenanthrene are represented as percentage response corresponding to its control transient.

INa was elicited by 50 ms depolarising square pulses from the holding potential of -120 mV to +60 mV in 10 mV steps. The frequency of pulses was 1 Hz. ICaL was elicited by repetitive 250 ms depolarising pulses from -40 mV to 0 mV, since the voltage for maximal peak ICaL, is 0 mV. Strong run-down of ICaL is typical for ventricular myocytes and particularly so in navaga. Therefore, to elucidate effects of phenanthrene, we compared the relative ICaL density expressed as a % of current recorded before run-down, in control cells and cells superfused with different concentrations of phenanthrene. Effects of phenanthrene on ICaL were studied only in ventricular cells, since in navaga atrial myocytes the current amplitude was exceedingly small and the run-down made the evaluation of phenanthrene effects impossible. Future work on ICa in navaga should consider performing experiments in perforated patch-clamp mode.

2.7. Statistics

The results are represented as means ± SEM. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Normality of distribution and equality of variances were checked, and necessary transformation of variables were made before statistical testing. The densities of ionic currents and AP parameters were compared using two-way ANOVA followed with Dunnett's or Sidak's post hoc tests. In all sets of experiments, except ICaL measurements, repeated measures were compared, and p values of < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Statistical details including n values for myocytes and N values for fish, can be found in the figure legends. Additionally, we include Table 1 for the complete list of experimental N and n values, which conform to physiological and pharmacological norms. Please note that a single fish could be used to obtain both atrial and ventricular myocytes, which could then be used for recordings of different currents. This helped to reduce the total number of fish required which is a consideration when collecting from the wild.

Table 1.

Numbers of animals and cells used in the study.

| Type of recording | Cell type | Fish weight, g | Number of fish (N) | Number of cells (n) |

| APs | Ventricular | 89.9 ± 21.1 | 3 | 13 |

| IKr double pulse | Atrial | 83.4 ± 9.7 | 3 | 11 |

| Ventricular | 79.7 ± 7.8 | 4 | 13 | |

| IKr AP-like protocol | Atrial | 86.5 ± 11.8 | 3 | 10 |

| Ventricular | 86.5 ± 11.8 | 3 | 11 | |

| INa | Atrial | 101.3 ± 16.6 | 4 | 14 |

| Ventricular | 101.3 ± 16.6 | 4 | 14 | |

| ICaL | Ventricular | 87 ± 13.6 | 4 | Time-control – 9 Phe 3 μM – 7 Phe 10 μM – 10 Phe 30 μM - 9 |

| TOTAL | 86.8 ± 5.9 | 14 | 121 |

3. Results

3.1. Phenanthrene prolongs APs in ventricular myocytes from navaga heart

We first investigated the effect of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene on electrical activity in ventricular myocytes using current-clamp mode of whole-cell patch-clamp (Fig. 1a). While 1 and 3 µM had no significant effect on AP duration, 10 µM phenanthrene induced a large and significant prolongation of AP duration at both 50% (APD50) (527 ± 12 ms to 873 ± 93 ms; n = 13, N = 3) and 90% (APD90) (586 ± 14 ms to 1003 ± 106 ms; n = 13, N = 3) repolarization (Fig. 1b). Resting membrane potential (RMP), AP amplitude (APA) and maximal upstroke velocity (dV/dtmax) were not affected by phenanthrene (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Effects of phenanthrene on AP waveform in navaga ventricular myocytes. (a) Original recordings of APs in a representative ventricular myocyte during control conditions and in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene. Mean data (± SEM, n = 13, N = 3) showing the effect of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene on (b) AP duration at 50% (APD50) and 90% (APD90) repolarization, and (c) on amplitude (APA), resting membrane potential (RMP) and maximal AP upstroke velocity (dV/dtmax) in navaga ventricular myocytes. *p<0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test.

3.2. Phenanthrene suppresses IKr but not IK1 or IKACh, in navaga atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes

As prolongation of AP has previously been attributed to the inhibition of IKr repolarising current, the next stage of our study was to investigate phenanthrene effects on all major repolarising currents in navaga atrial and ventricular myocytes (IKr, IK1, IKACh). IKr is the main repolarising current in atrial and ventricular navaga myocytes (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2015). In our experiments, 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene were applied consecutively, followed by E-4031 (IKr inhibitor) at supramaximal concentration of 5 µM. The residual current recorded under E-4031 was subtracted from recordings obtained in control conditions and in the presence of phenanthrene. Phenanthrene exhibited significant concentration-dependent inhibition of IKr peak tail currents (Fig. 2) in both atrial (Fig. 2a, b) and ventricular (Fig. 2d) myocytes. 1 µM phenanthrene produced significant reduction of IKr by 26.4 ± 2.1% and 25.5 ± 3.5% in atrial and ventricular myocytes, respectively, at voltages between 20 and 60 mV, while 10 µM phenanthrene almost abolished the current (Fig. 2b, d). IC50 values of 1.95 ± 0.1 µM (hill slope 1.4 ± 0.1; n = 11, N = 3) and 2.2 ± 0.3 µM (hill slope 1.1 ± 0.1; n = 13, N = 4) were obtained for atrial and ventricular IKr, respectively (Fig. 2c, e).

Fig. 2.

Effect of phenanthrene on K+ rapid delayed rectifier current (IKr) in navaga cardiac myocytes. (a) The current was elicited by a double square-pulse comand waveform protocol from the holding potential of -80 mV with activating pulses to +40 mV, followed by a repolarising test pulse to -20 mV to elicit the IKr tail current (top). Original recordings of IKr from a representative atrial myocyte in control conditions and in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene (bottom). (b, d) Mean ± SEM I-V curves of tail IKr in atrial (b, n = 11, N = 3) and ventricular (d, n = 13, N = 4) myocytes under control conditions and in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene. Mean values of IKr were obtained after subtraction of current recorded in the presence of 5 µM E-4031 (see methods). (c, e) Concentration-response curves showing the potency of phenanthrene on IKr tails in atrial (c) and ventricular (e) myocytes, respectively yielding IC50 values of 1.95 ± 0.1 µM (hill slope 1.4 ± 0.1, n = 11, N = 3) and 2.2 ± 0.3 µM (hill slope 1.1 ± 0.1, n = 11, N = 4). *p<0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test.

In contrast to IKr, both IK1 and IKACh inward rectifiers appeared to be completely insensitive to phenanthrene. At 30 µM, phenanthrene failed to affect IK1 in navaga ventricular myocytes (see Supplement Fig. 1a; n = 5, N = 2). ACh (10 µM) induced a strong IKACh current in atrial, but not ventricular myocytes from navaga heart (see methods), but superfusion of up to 30 µM phenanthrene had no effect on the IKACh current induced by 10 µM ACh (Supplement Fig. 1b, c; n = 4, N = 2).

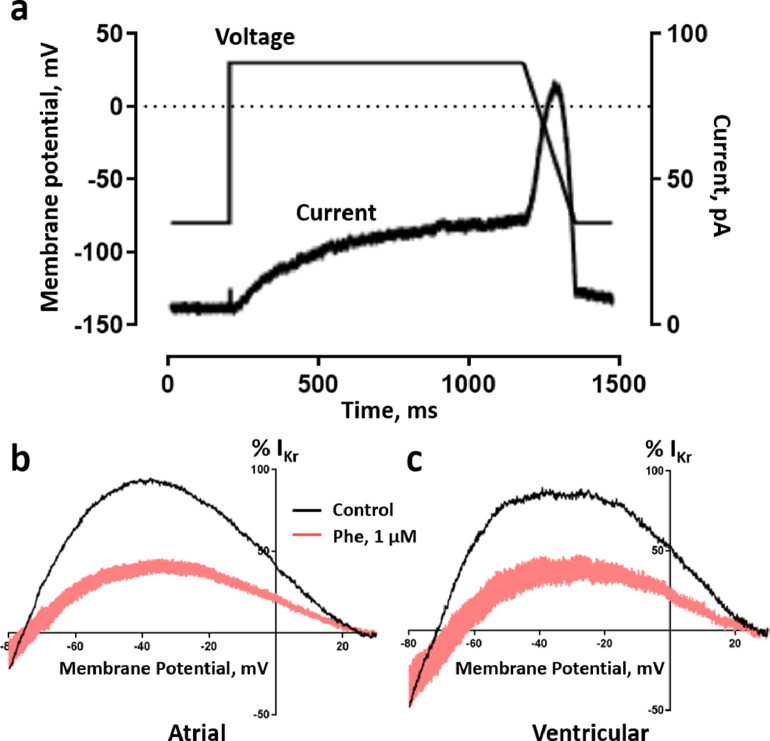

3.3. Effect of phenanthrene on protective IKr transient currents

To further investigate the cardiotoxic and proarrhythmic effects of phenanthrene on navaga myocytes, we examined its impact on IKr transient outward currents elicited by a double-pulse paired AP-like command waveform protocol (Fig. 3a). A robust envelope of IKr transient currents were elicited in both atrial (Fig. 3b) and ventricular myocytes (raw traces not shown) in response to premature depolarising stimuli, introduced from APD90 – 90 ms to APD90 + 90 ms. Under control conditions, IKr transients peaked at 25 ms post APD90 in atrial cells (Fig. 3e) and at 10 ms post-APD90 in ventricular cells (Fig. 3f). 1 µM phenanthrene induced significant inhibition of peak transients current over the whole range of depolarising stimuli both in atrial (Fig. 3c, e) and ventricular (Fig. 3f) myocytes. The magnitude of the inhibition of the peak transient current was 58.3 ± 6.6% in atrial (n = 10, N = 3) and 55.8 ± 5.4% in ventricular cells (n = 11, N = 3). No significant difference in extent of current inhibition at different levels of repolarization was found (p>0.05, two-way ANOVA). These results suggest that protective IKr transient currents in navaga heart is sensitive to phenanthrene. Similar inhibitory effects of 1 µM phenanthrene were observed on the IKr repolarising current of both atrial (53.4 ± 4.3%) and ventricular (50 ± 6.3%) myocytes (Fig. 4b, c, respectively; n = 10, N = 3, for both cell types), elicited by AP-like voltage command waveform (Fig. 4a). Robust bell-shaped current during the repolarising voltage ramp was observed under control conditions (Fig. 4a), like that previously reported for human ERG channel (Hancox et al., 1998).

Fig. 3.

Effect of phenanthrene on response of IKr to premature stimulation. (a) Magnified view of (inset) paired ventricular AP-like command waveform protocol. Representative trace of families of transient currents elicited corresponding to each depolarization in an atrial myocyte in (b) absence, (c) presence of 1 µM phenanthrene and (d) 5 µM E-4031. (e, f) Percentage response of peak IKr transients in atrial (e, n = 10, N = 3) and ventricular (f, n = 11, N = 3) navaga myocytes in absence (black) and presence (pink) of 1 µM phenanthrene. Peak IKr transients for each cell under control conditions were normalized to the maximal current transient during the protocol. Peak IKr transients in presence of 1 µM phenanthrene are represented as percentage response relative to its corresponding percentage control transient. All data represented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Sidak's post-hoc test.

Fig. 4.

Phenanthrene inhibits repolarising IKr during AP-like command in myocytes from navaga heart. (a) Representative trace of IKr elicited by AP-like voltage command waveform (shown as voltage trace) in an atrial myocyte. (b, c) Mean ± SEM percentage response of IKr to 1 µM phenanthrene in atrial (b) and ventricular (c) myocytes from navaga heart exhibiting an inhibition of 53.4 ± 4.3 and 50 ± 6.3% respectively (n = 10; N = 3; p<0.05, Student's paired t-test).

3.4. Phenanthrene inhibits inward currents only at high concentrations

Fast Na+ current (INa) was insensitive to 1 µM phenanthrene, however concentrations of 3 and 10 µM produced a very modest, but significant inhibitory effect (Fig. 5a, c, d). Inhibition of maximal peak INa (at -20 mV) by 10 µM phenanthrene was 17.5 ± 3.9% in atrial (Fig. 5c) and 16.9 ± 4.1% in ventricular (Fig. 5d) cells (n = 14, N = 4, for both cell types).

Fig. 5.

Effect of phenanthrene on fast Na+ current (INa) in navaga cardiac myocytes. (a) Original recordings of INa elicited by depolarization to -20 mV in a representative atrial myocyte in control conditions and in the presence of 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene. (b) The protocol used to elicit INa and to test the I-V relationship. (c, d) Mean ± SEM I-V curves of INa in atrial (c, n = 14, N = 4) and ventricular (d, n = 14, N = 4) myocytes in control conditions and in the presence of 1, 3 and 10 µM phenanthrene. *p<0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test.

Navaga exhibited differential l-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) densities in atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes with marked run-down of the current over time in both cell types. In atrial cells, ICaL was less than 0.3 pApF−1 after obtaining whole-cell configuration and in 1–2 min decreased to the noise level, thus testing the effect of phenanthrene was impractical (data not shown). Ventricular ICaL was 3.3 ± 0.34 pApF−1 but also showed strong run-down over time (Fig. 6a). Therefore, we recorded peak ICaL during repetitive depolarizations to 0 mV and compared the current in control conditions (time-control; n = 9, N = 4) and in the presence of phenanthrene. While 3 µM phenanthrene showed no effect (n = 7, N = 4), 10 µM (n = 10, N = 4) and 30 µM (n = 10, N = 4) tended to decrease ICaL greater than its decrease in time-matched controls (Fig. 6b, c, d). However, this effect was statistical significance only in the case of 30 µM phenanthrene.

Fig. 6.

Effect of phenanthrene on l-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) in navaga ventricular myocytes. (a) Original trace of ICaL elicited by depolarization to 0 mV from the holding potential of -40 mV after break through into whole-cell mode (0 min) and after 3.5 min of recording in control conditions showing the significant time-dependent current run-down. (b) The same as (a) but in the presence of 30 µM phenanthrene showing the combined effect of phenanthrene inhibition and run-down on the amplitude of ICa. (c) Time-dependent changes of mean values of peak ICaL at 0 mV recorded in control conditions and in the presence of 3, 10 and 30 µM phenanthrene. Arrow shows the time of phenanthrene application. (d) Comparison of peak ICaL at 0 mV after 3.5 min of recording in control conditions and in the presence of 3, 10 and 30 µM phenanthrene. Current values in (c) and (d) are expressed as% of current amplitude at the start of recording (before run-down). *p<0.05, two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of phenanthrene, a known cardiotoxic pollutant associated with diesel and crude oil, on the heart function of the navaga cod. We hypothesised that acute exposure to phenanthrene would (1) inhibit repolarising K+ channel currents in both cell types; causing (2) AP prolongation thus setting up a proarrhythmic cardiac phenotype; and (3) depress cellular Ca2+ cycling in atrial and ventricle myocytes. Our data confirms that phenanthrene is acutely and directly cardiotoxic to fish (Brette et al., 2017; Ainerua et al., 2020a, Vehniäinen et al., 2019). We show that phenanthrene increased AP duration in ventricular myocytes due to inhibition of the repolarising IKr current. We also show inhibition of the protective outward IKr transients by phenanthrene in atrial and ventricular myocytes which would make the heart vulnerable to arrhythmias. Finally, we show inhibition of the Ca2+ current (ICa) which could depress contractile function. These findings allow us to accept our hypotheses whilst revealing novel chamber- and species-specific differences in phenanthrene potency. Additionally, we present novel data on the impact of phenanthrene on the inward Na+current (INa, inhibitory) and the ligand gated K+ current (IKACh, no effect).

4.1. Phenanthrene prolongs action potential duration and has differing effects on K+ currents

The shape of the cardiac AP depends on the synchronous activity and expression of various underlying ion channels. The limited number of studies which have investigated the effect of phenanthrene on AP characteristics in fish have shown species-specific responses. While initial studies in scombrid fishes (Thunnus albacares, Scomber japonicus, Thunnus orientalis), mahi-mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) showed AP duration prolongation (Brette et al., 2017; Heuer et al., 2019; Ainerua et al., 2020a) recent studies with rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) reported shortening of AP in the presence of phenanthrene (Vehniäinen et al., 2019; Kompella et al., 2021). In the current study, we observed a prolongation of AP duration at both 50% and 90% repolarisation at 10 µM phenanthrene but not at the lower concentrations of 1 or 3 µM (Fig. 1). The lack of APD shortening in our study suggest minimal effects of phenanthrene on inward currents (Ainerua et al., 2020a; Vehniäinen et al., 2019) (discussed further below in Section 4.3). The prolongation at 90% repolarisation strongly implicates effects on IKr as it is the major repolarising current in this species; IKs and Ito have not been registered in previous studies (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2015). Indeed, Fig. 2d, e clearly shows the strong inhibitory effect of phenanthrene on navaga ventricular Ikr (IC50 value of 2.2 ± 0.3 µM). This is more potent than that previously reported for zebrafish, brown trout, bluefin tuna, and rainbow trout with IC50 values of 3, 7, 5 and 10 µM, respectively (Brette et al., 2017; Vehniäinen et al., 2019; Kompella et al., 2021; Ainerua et al., 2020b), further exemplifying species-specific differences in pharmacology. The finding of slightly greater potency in navaga atrium (IC50 value of 1.95 ± 0.1 µM, Fig. 2d) may represent differences in chamber sensitivity and needs to be tested in other fish species.

In agreement with all previous work (Brette et al., 2017; Heuer et al., 2019; Ainerua et al., 2020a; Vehniäinen et al., 2019) phenanthrene had no effect on the resting membrane potential (Fig. 1c) or the inward rectifier current (IK1, Sup. Fig. 1a) indicating that basal excitability of the heart is unaffected by this pollutant. This is reassuring in relation to the dual pressures of pollution and climate change. Recent work has identified a mismatch between inward and outward currents that can inhibit cardiac excitability during warming – the temperature-dependent deterioration of electrical excitability (TDEE) hypothesis (Haverinen and Vornanen, 2020). This hypothesis has recently been tested in the navaga; warming was found to hyperpolarise the cell membrane but not impact excitability (Abramochkin et al., 2019). Thus, it appears that unlike more northern temperate species (Haverinen and Vornanen, 2020; Badr et al., 2018), excitability due to resting membrane potential in the ventricle of this polar fish is resistant to both temperature and a key petroleum pollutant. In vivo, the resting membrane potential of navaga atrial myocytes is maintained, at least in part, through vagal tone which activates the ACh-dependent inward rectifier IKACh (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2017). Once the atrial myocytes are isolated and lose this tone, they depolarise as the density of their inward rectifier current IK1 is very small (Abramochkin and Vornanen, 2015). This means that it is impossible to measure AP from navaga atrial cells using current-clamp. However, it did provide us with the impetus to perform the first measurements of the impact of phenanthrene on IKACh. Phenanthrene had no effect on the IKACh current, even at doses as high as 30 µM (Sup. Fig. 1b, c). This is the first study we are aware of to test this compound on any ligand-gated ion channel and future studies should test the consistency of this response.

4.2. Impact of phenanthrene on protection from arrhythmia in navaga

With unique gating kinetics, IKr currents elicit fast outward transient currents in response to a premature depolarization stimulus, such as an early-after-depolarization (Perry et al., 2015). These fast-outward transient currents repolarise the membrane and lead to shorter intermittent action potentials which enable the heart to recover to normal rhythm. Inhibition of IKr transient currents reduces this protection from premature depolarizations and can significantly disrupt heart rhythm leading to arrhythmia and even heart attack (Vandenberg et al., 2012). In view of the potent IKr inhibition observed with tail currents (Fig. 2), we tested the effects of phenanthrene on IKr protective transient currents. Both atrial and ventricular myocytes of navaga elicited robust IKr transient currents which peaked at 25 ms and 10 ms post-APD90 respectively (Fig. 3e, f) which is consistent with a recent study showing significant inhibition of native IKr transient currents by phenanthrene in zebrafish ventricular myocytes (Kompella et al., 2021). This is the second study that we know of to record the native IKr protective transient currents in a fish or any other ectotherm and the first we know of for atrial myocytes. Most previous studies investigating this role of IKr have been conducted in expression systems using human erg channels (which drive the human IKr current) (Du et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2001). We found 1 µM phenanthrene exhibited significant inhibition of these IKr transient outward currents (~55%, Fig. 3) in navaga, which was greater than the inhibition of the IKr tail-currents (~25%, Fig. 2). A greater inhibition (~50%) was also observed in the instantaneous IV curve obtained during the repolarising ramp phase of the AP-like voltage protocol (Fig. 4). These data reveal a unique IKr pharmacology in response to phenanthrene exposure that exacerbates the proarrhythmic potential of this pollutant on fish cardiac function.

4.3. Impact of phenanthrene on inward currents

Electrical excitability is dominated by two inward conductances in fish myocytes: the fast-inward Na+current (INa) and the L-type Ca2+ current (ICa). Phenanthrene inhibits both ion currents in the navaga heart. We found a small (~17%) but consistent inhibition of ICa in navaga ventricular myocytes after exposure to 30 µM phenanthrene, which is less than the 50% inhibition observed in trout (Vehniäinen et al., 2019; Ainerua et al., 2020b) and zebrafish (Kompella et al., 2021), and the 75% inhibition observed in bluefin tuna (Brette et al., 2017) under similar conditions. This reduced potency on navaga ICa underlies the prolongation of AP at 50% repolarization. We did not measure the impact of the reduction in ICa on contractility in navaga, but a moderate depression of contractile force would be expected if other Ca2+ flux pathways are unable to compensate (Heuer et al., 2019; Ainerua et al., 2020b). Due to the run-down of ICa in navaga, future studies of this current should be conducted using perforated patch-clamp.

We found consistent inhibition (~17%, at 10 µM) of INa in atrial and ventricular myocytes in the current study. This contrasts with rainbow trout ventricular myocytes where a small increase in INa amplitude has been observed (Vehniäinen et al., 2019). We have no explanation for the difference between studies and encourage greater attention to the effect of phenanthrene on Na+ conductances in future work. There is also a discrepancy between the INa inhibition we observed for navaga, and the lack of a change in the upstroke velocity of the AP. It may be that the current injected to raise the voltage of the membrane to its threshold was too strong to observe small changes in dV/dt. However, the lack of a sizable AP overshoot argues against this. Future work could use sharp microelectrode impalement to better resolve AP upstroke in multicellular preparations.

5. Conclusions

A healthy cardiovascular system is required for fitness and thus studying how the fish heart is impacted by pollutants associated with fossil fuels is paramount for predicting the survival of individual fish and of populations of fishes. Here we show that the low molecular weight PAH, phenanthrene, at doses between 1 and 30 µM cause changes in cellular ion fluxes than can cause cardiac dysfunction in the polar fish, the navaga cod. Although there are no studies investigating phenanthrene concentrations in the blood of navaga (or any other fish we are aware of), limited studies in human blood show phenanthrene concentrations in nanomolar range whereas tissue concentrations as high as 3 µM (Huang et al., 2016; Camacho et al., 2012). Therefore, the concentrations used in this study, specifically the reported IKr IC50 values between 1.9–2.2 µM are biologically relevant and could have proarrhythmic consequences. Our previous work has demonstrated how changes in ion flux in cardiomyocytes led to reductions in contractility and electrical activity of the whole trout heart (Ainerua et al., 2020a). Following the schema proposed for trout, we suggest that the inhibition of the inward rectifying K+ current (IKr) and the cellular Ca2+ flux pathways reported here are expected to diminish contractile function and induce a proarrhythmic phenotype in navaga exposed to PAHs in their environment. Warming is also known to induce electrical instability (Vornanen, 2016) and reduce contractile function in fish (Farrell et al., 1996). Thus, the combination of warming and pollution from leaks associated with oil and gas exploration are an area of grave concern for the Arctic and an important challenge to be addressed in future studies.

Authors' contribution

Denis V Abramochkin conducted the study, performed analysis, prepared figures, and drafted parts of the manuscript. Shiva N Kompella was involved in the experimental design, data analysis, figure preparation and in drafting parts of the manuscript. Holly A Shiels conceptualized the study and was involved in data analysis, figure preparation and writing, reviewing, and editing the final manuscript. All authors approved final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by British Heart Foundation Grant PG/17/77/33125 to HAS and SNK and by the Interdisciplinary Scientific and Educational School of Moscow University «Molecular Technologies of the Living Systems and Synthetic Biology» as part of the Scientific Project of the State Order of the Government of Russian Federation to Lomonosov Moscow State University No.121032300071-8 to DVA. We thank Prof Jules Hancox, University of Bristol, UK, and Dr Fabien Brette, Université de Bordeaux for insightful comments. We are grateful to White Sea Biological Station director, Professor Alexander Tzetlin for supporting the study. We thank Valo and Valentina Sivonen for collecting the fish.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2021.105823.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Overland J, Walsh J., Kattsov V.Snow. 2017. Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic. In: Programme AMaA, editor. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle JR, Kjellén U, Haugerud O. Decision on oil and gas exploration in an Arctic area: case study from the Norwegian Barents Sea. Saf. Sci. 2009;47(6):832–842. [Google Scholar]

- Silber GK, Adams JD. Vessel operations in the Arctic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019;6(573):2015–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. Rights and responsibilities: sustainability and stakeholder relations in the Russian oil and gas sector. In: Fondahl G., Wilson G.N., editors. Northern Sustainabilities: Understanding and Addressing Change in the Circumpolar World. Springer Polar Sciences; Springer, Cham: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keil K. Governing Arctic Change. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2017. The Arctic in a global energy picture: international determinants of Arctic oil and gas development. Keil K. KS, editor. [Google Scholar]

- Krupenio NN PI, Parmuzin PI, Zamoiskii VL. Mapping of segments polluted by petroleum products in the usinsk region of the Komi republic from remote-measurement data. Hydrotech. Constr. 1995;1(11):648–652. 29. [Google Scholar]

- AMAP. Biological effects of contaminants on Arctic wildlife and fish. Summary for policy-makers. In: (AMAP) AMaAP, editor. Oslo, Norway 2019.

- AMAP. Chemicals of emerging Arctic concern. Summary for policy-makers. In: (AMAP) AMaAP, editor. Oslo, Norway 2017.

- Le Bihanic F, Clérandeau C, Le Menach K, Morin B, Budzinski H, Cousin X. Developmental toxicity of PAH mixtures in fish early life stages. Part II: adverse effects in Japanese medaka. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014;21(24):13732–13743. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2676-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas J, Perrichon P, Nouhaud M, Audras A, Leguen I, Lefrancois C. Aerobic metabolism and cardiac activity in the descendants of zebrafish exposed to pyrolytic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014;21(24):13888–13897. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Defects in cardiac function precede morphological abnormalities in fish embryos exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;196(2):191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Carls MG, Teraoka H, Sloan CA, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-independent toxicity of weathered crude oil during fish development. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005:113. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Carls MG, Day HL, Sloan CA, Bolton JL, Collier TK. Cardiac arrhythmia is the primary response of embryonic Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) exposed to crude oil during weathering. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009:43. doi: 10.1021/es802270t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemo OK, Kroll KJ, Denslow ND. Developmental abnormalities and differential expression of genes induced in oil and dispersant exposed Menidia beryllina embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015;168:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP. Molecular mechanisms of crude oil developmental toxicity in fish. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2017;73(1):19–32. doi: 10.1007/s00244-017-0381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Day HL, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Developmental toxicity of 4-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in zebrafish is differentially dependent on AH receptor isoforms and hepatic cytochrome P4501A metabolism. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;217(3):308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brette F, Machado B, Cros C, Incardona JP, Scholz NL, Block BA. Crude oil impairs cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in fish. Science. 2014;343(6172):772–776. doi: 10.1126/science.1242747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brette F, Shiels HA, Galli GL, Cros C, Incardona JP, Scholz NL. A novel cardiotoxic mechanism for a pervasive global pollutant. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep41476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud C, Eriksson A, Krasnov A, Wincent E, Pakkanen H, Lehtivuori H. Retene, pyrene and phenanthrene cause distinct molecular-level changes in the cardiac tissue of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) larvae, part 1–transcriptomics. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud C, Eriksson A, Rokka A, Skaugen M, Lihavainen J, Keinänen M. Retene, pyrene and phenanthrene cause distinct molecular-level changes in the cardiac tissue of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) larvae, part 2 – proteomics and metabolomics. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;746 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carls M, Rice S, Hose J. Low-level exposure during incubation causes malformations, genetic damage, and mortality in larval Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1999;18:481–493. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer RM, Galli GLJ, Shiels HA, Fieber LA, Cox GK, Mager EM. Impacts of deepwater horizon crude oil on Mahi-Mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) heart cell function. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53(16):9895–9904. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainerua MO, Tinwell J, Kompella SN, Sørhus E, White KN, van Dongen BE. Understanding the cardiac toxicity of the anthropogenic pollutant phenanthrene on the freshwater indicator species, the brown trout (Salmo trutta): from whole heart to cardiomyocytes. Chemosphere. 2020;239 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Heuer RM, Cox GK, Stieglitz JD, Hoenig R, Mager EM. Effects of crude oil on in situ cardiac function in young adult mahi–mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) Aquat. Toxicol. 2016;180:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehniäinen ER, Haverinen J, Vornanen M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons phenanthrene and retene modify the action potential via multiple ion currents in rainbow trout oncorhynchus mykiss cardiac myocytes. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019;38(10):2145–2153. doi: 10.1002/etc.4530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marris CR, Kompella SN, Miller MR, Incardona JP, Brette F, Hancox JC. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons in pollution: a heart-breaking matter. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2020;598(2):227–247. doi: 10.1113/JP278885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermini B, Hancox JC, bi-Gerges N, Bridgland-Taylor M, Chaudhary KW, Colatsky T. A new perspective in the field of cardiac safety testing through the comprehensive in vitro proarrhythmia assay paradigm. JBiomolScreen. 2016;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1177/1087057115594589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Jia H, Sun Y, Yu H, Wang X, Wu J. Bioaccumulation and ROS generation in liver of Carassius auratus, exposed to phenanthrene. Compar. Biochem. Physiol. Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007;145(2):288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza RS, Trevisan R, Flores-Nunes F, Toledo-Silva G, Wendt N, Mattos JJ. Exposure to phenanthrene and depuration: changes on gene transcription, enzymatic activity and lipid peroxidation in gill of scallops Nodipecten nodosus. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016;177:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Huang L, Wang C, Gao D, Zuo Z. Phenanthrene exposure produces cardiac defects during embryo development of zebrafish (Danio rerio) through activation of MMP-9. Chemosphere. 2013;93(6):1168–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AL, Steffensen JF. The Arctic and Antarctic polar marine environments. Fish Physiol. 2005;22:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Abramochkin DV, Vornanen M. Seasonal changes of cholinergic response in the atrium of Arctic navaga cod (Eleginus navaga) J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2017;187(2):329–338. doi: 10.1007/s00360-016-1032-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramochkin DV, Vornanen M. Seasonal acclimatization of the cardiac potassium currents (IK1 and IKr) in an arctic marine teleost, the navaga cod (Eleginus navaga) J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2015;185(8):883–890. doi: 10.1007/s00360-015-0925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen M, Abramochkin DV, Vornanen M. Seasonal acclimatization of the cardiac action potential in the Arctic navaga cod (Eleginus navaga, Gadidae) J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2014;184(3):319–327. doi: 10.1007/s00360-013-0797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Xi Z, Wang C, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Zhang S. Phenanthrene exposure induces cardiac hypertrophy via reducing miR-133a expression by DNA methylation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20105. doi: 10.1038/srep20105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M, Boada LD, Orós J, Calabuig P, Zumbado M, Luzardo OP. Comparative study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in plasma of Eastern Atlantic juvenile and adult nesting loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012;64(9):1974–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marris CR, Kompella SN, Miller MR, Incardona JP, Brette F, Hancox JC. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons in pollution: a heart-breaking matter. J. Physiol. 2020;598(2):227–247. doi: 10.1113/JP278885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kompella SN, Brette F, Hancox JC, Shiels HA. Phenanthrene impacts zebrafish cardiomyocyte excitability by inhibiting IKr and shortening action potential duration. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021;153(2) doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M. Sarcolemmal Ca influx through L-type Ca channels in ventricular myocytes of a teleost fish. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.5.R1432. R1432-R40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove-Madsen L, Tort L. L-type Ca2+ current and excitation-contraction coupling in single atrial myocytes from rainbow trout. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275(6):2061–2069. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R2061. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M, Hassinen M, Haverinen J. Tetrodotoxin sensitivity of the vertebrate cardiac Na+ current. Mar. Drugs. 2011;9(11):2409–2422. doi: 10.3390/md9112409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M, Ry”kkynen A, Nurmi A. Temperature-dependent expression of sarcolemmal K+ currents in rainbow trout atrial and ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;282 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00349.2001. R1191-R9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg JI, Perry MD, Perrin MJ, Mann SA, Ke Y, Hill AP. hERG K(+) channels: structure, function, and clinical significance. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92(3):1393–1478. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancox JC, Levi AJ, Witchel HJ. Time course and voltage dependence of expressed HERG current compared with native” rapid” delayed rectifier K current during the cardiac ventricular action potential. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;436(6):843–853. doi: 10.1007/s004240050713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainerua MO, Tinwell J, Kompella SN, Sorhus E, White KN, van Dongen BE. Understanding the cardiac toxicity of the anthropogenic pollutant phenanthrene on the freshwater indicator species, the brown trout (Salmo trutta): from whole heart to cardiomyocytes. Chemosphere. 2020;239 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverinen J, Vornanen M. Reduced ventricular excitability causes atrioventricular block and depression of heart rate in fish at critically high temperatures. J. Exp. Biol. 2020;223 doi: 10.1242/jeb.225227. Pt 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramochkin DV, Haverinen J, Mitenkov YA, Vornanen M. Temperature and external K(+) dependence of electrical excitation in ventricular myocytes of cod-like fishes. J. Exp. Biol. 2019;222 doi: 10.1242/jeb.193607. Pt 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr A, Korajoki H, Abu-Amra ES, El-Sayed MF, Vornanen M. Effects of seasonal acclimatization on thermal tolerance of inward currents in roach (Rutilus rutilus) cardiac myocytes. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2018;188(2):255–269. doi: 10.1007/s00360-017-1126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MD, Ng CA, Mann SA, Sadrieh A, Imtiaz M, Hill AP. Getting to the heart of hERG K(+) channel gating. J. Physiol. 2015;593(12):2575–2585. doi: 10.1113/JP270095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du CY, Adeniran I, Cheng H, Zhang YH, El Harchi A, McPate MJ. Acidosis impairs the protective role of hERG K+ channels against premature stimulation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2010;21(10):1160–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Mahaut-Smith MP, Varghese A, Huang CL, Kemp PR, Vandenberg JI. Effects of premature stimulation on HERG K(+) channels. J. Physiol. 2001;537:843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00843.x. Pt 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M. The temperature dependence of electrical excitability in fish hearts. J. Exp. Biol. 2016;219(13):1941–1952. doi: 10.1242/jeb.128439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP, Gamperl AK, Hicks JMT, Shiels HA, Jain KE. Maximum cardiac performance of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) at temperatures approaching their upper lethal limit. J. Exp. Biol. 1996;199:663–672. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.