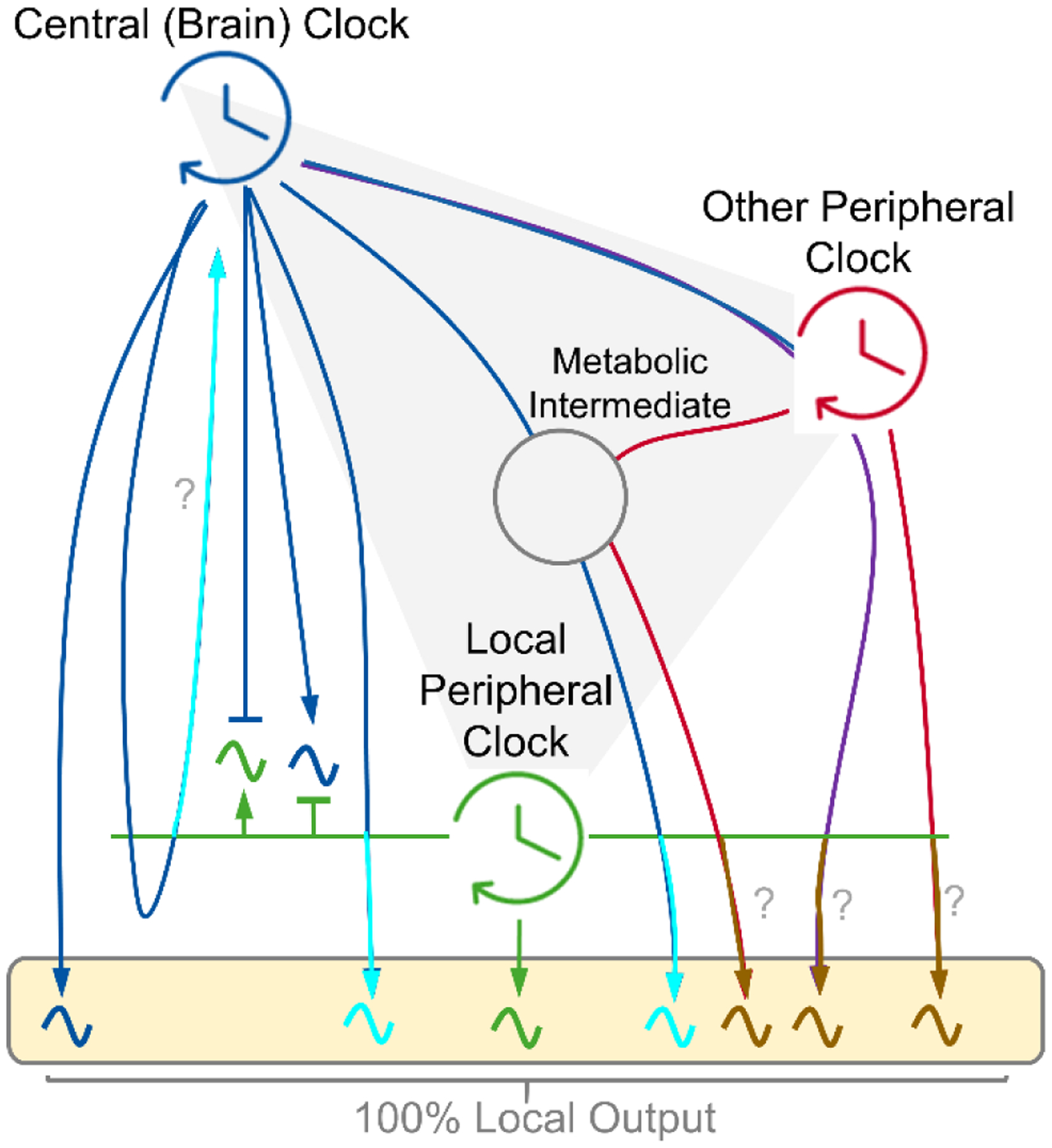

Figure 4. Inputs determining peripheral clock output.

Conceptual model showing the drivers of circadian output of a peripheral metabolic tissue. Arrows indicate a driving circadian signal. The box depicts 100% of the local oscillatory output. Local clocks exhibit autonomy in driving a small fraction of output (green) (54) (53). Central (brain) clock-controlled cycles, feeding-fasting and sleep-wake, can drive rhythms independently or presumably in cooperation with the local clock (blue and turquoise). Peripheral clocks may influence rhythmicity of each other in a central clock dependent or independent manner (red, purple and brown). Many circadian signals likely synergize across tissues and intermediates (e.g. gut microbiota) to shape the full rhythmic output, with mechanisms which remain elusive (gray). It is unclear if the local clock is required for certain connections (?).